Measuring the Effectiveness of the Project Management Information System (PMIS) on the Financial Wellness of Rural Households in the Hill Districts of Uttarakhand, India: An IS-FW Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. DeLone & McLean Updated Information Success Model

2.2. PMIS Quality

2.3. Information Quality

2.4. Service Quality

2.5. Net Benefits of PMIS

2.6. Outcome and Impact of PMIS

2.7. Net Benefits of PMIS and Financial Behavior

2.8. Savings Behavior and Financial Behavior

2.9. Cash Management and Financial Behavior

2.10. Risk-Credit Management and Financial Behavior

2.11. Net Benefits of PMIS and Financial Attitude

2.12. Financial Wellness

2.13. Financial Behavior and Financial Wellness

2.14. Financial Attitude and Financial Wellness

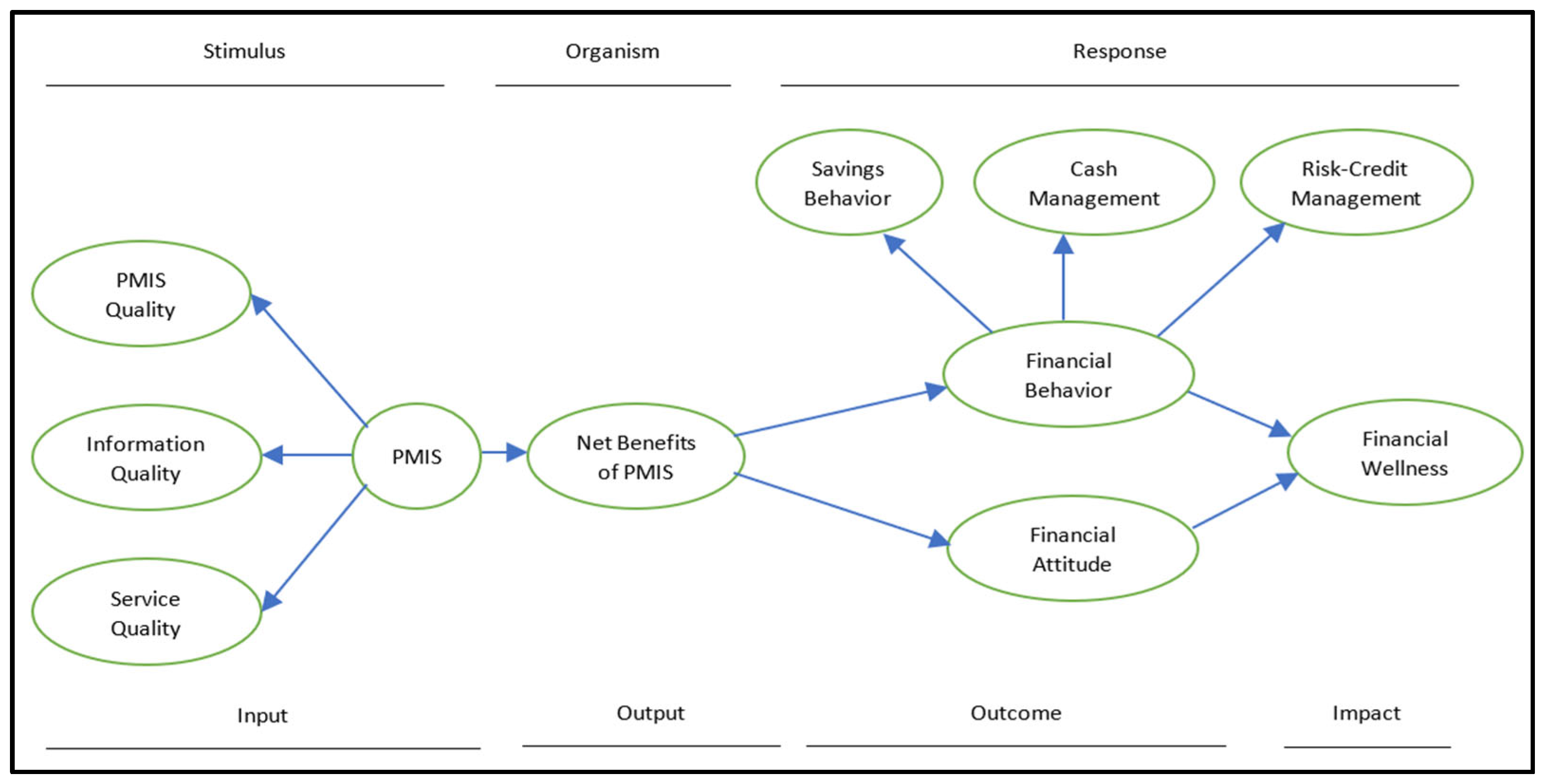

3. Information System-Financial Wellness (IS-FW) Model

3.1. IS-FW Model and Logical Framework Approach (LFA)

3.2. IS-FW Model and Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) Framework

4. Research Method

5. Data Analysis and Results

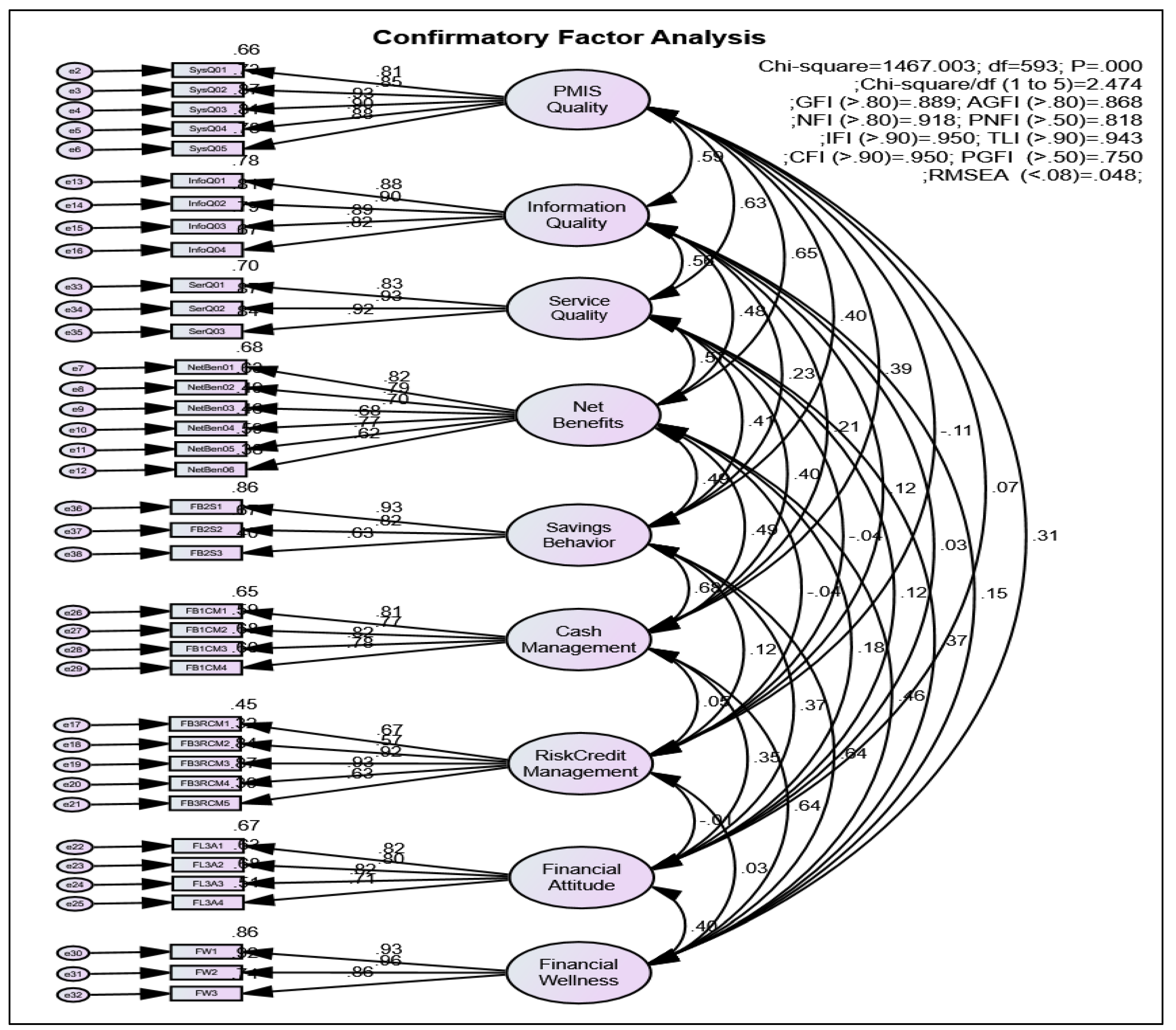

5.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

5.2. Structured Model

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Theoretical Implications

9. Practical Implications

10. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| SN. | Variables | Constructs | Notation | Questionnaire |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Easy to Operate | PMIS Quality | SysQ01 | PMIS is easy to operate and search records. |

| 2 | System Functionality | SysQ02 | PMIS has features that help in financial record keeping, implementation of activities, business activities, decision making, and other activities. | |

| 3 | Representation of Data | SysQ03 | PMIS provides charts of our business data and financial data. | |

| 4 | Usability | SysQ04 | Based on our monthly activities, PMIS provides a monthly performance chart. We take a printout and review our Cooperative and our staffs’ performance. | |

| 5 | Usability | SysQ05 | PMIS does the grading of cooperatives, which shows our rank compared to other cooperatives. | |

| 6 | Decision Support | Information Quality | InfoQ01 | The monthly key performance chart of our cooperative provides the right direction for us. |

| 7 | Evidence | InfoQ02 | PMIS output report, i.e., demand-supply financial (savings, internal lending, etc.) helps us to make the decision. | |

| 8 | Accuracy | InfoQ03 | Reporting formats reflect accurate data that our staff entered. | |

| 9 | Easy to understand | InfoQ04 | PMIS reporting formats are easy to understand and clear. | |

| 10 | Assurance | Service Quality | SerQ01 | We have access to technical support for PMIS when needed. |

| 11 | Training | SerQ02 | We have received training on PMIS and financial management | |

| 12 | Training | SerQ03 | Our staff received frequent training on PMIS, financial management | |

| 13 | Implementation | Net Benefits | NetBen01 | PMIS facilitates in implementation of activities. |

| 14 | Save Time | NetBen02 | PMIS saves our time. | |

| 15 | Implementation | NetBen03 | PMIS improves services to the community members. | |

| 16 | GAP analysis | NetBen04 | PMIS helps us to analyze business data, and financial data | |

| 17 | Evaluation | NetBen05 | PMIS helps performance measurement. | |

| 18 | Knowledge Increase | NetBen06 | Our financial knowledge is increased after the information we receive. | |

| 19 | Budget Management | Cash Management | FB1CM1 | I make a monthly budget and strictly follow that. |

| 20 | Utility Bills | FB1CM2 | I always pay electric and water bills before the due date. | |

| 21 | Purchase Behavior | FB1CM3 | I always check purchase bills after buying daily consumption items from the market. | |

| 22 | Budget Management | FB1CM4 | I always keep track of my family expenses. | |

| 23 | Savings Behavior | Savings Behavior | FB2S1 | I always deposit extra money in my savings account. |

| 24 | Regular Savings | FB2S2 | I always contribute my monthly savings contribution towards SHG/PG. | |

| 25 | Savings Behavior (Negative) | FB2S3 | I prefer to have deposits in the account rather than more cash in hand. | |

| 26 | Loan | Risk-Credit Management | FB3RCM1 | I regularly pay loan instalments of Kisan Credit Card. |

| 27 | Health Insurance | FB3RCM2 | I have a health insurance policy for emergency health care expenses. | |

| 28 | Crop Insurance | FB3RCM3 | Every season, I purchase crop insurance to reduce financial losses caused by crop failure. | |

| 29 | Cattle Insurance | FB3RCM4 | My cattle are covered by insurance. | |

| 30 | Life Insurance | FB3RCM5 | I have a personal Life Insurance policy. | |

| 31 | Expenditure Attitude | Financial Attitudes | FL3A1 | I always bargain for almost everything that I buy. |

| 32 | Expenditure Attitude | FL3A2 | In making any purchase, generally, my first consideration is the cost. | |

| 33 | Expenditure Attitude | FL3A3 | I always like to buy input items from cooperatives because they give us more quality products at a lower price. | |

| 34 | Income Generating Activities | FL3A4 | I always participate in group, cooperative, and project activities. | |

| 35 | Income | Financial Wellness | FW1 | After joining the SHG/Cooperative, our income has increased. |

| 36 | Savings | FW2 | After joining the SHG/Cooperative, our savings have increased. | |

| 37 | Living Standards | FW3 | After joining the SHG/Cooperative, our living condition has improved. |

References

- Schneider, C.; Fuller, M.A.; Valacich, J.S.; George, J.F. Information Systems Project Management—A Process Approach; Golub, B.L., Ed.; Prospect Press: Burlington, VT, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781943153534. [Google Scholar]

- Laudon, K.C.; Laudon, J.P. Management Information System—Managing the Digital Firm, 16th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 9780135191798. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, H.; Shafique, M.N.; Rashid, A. Project Success in the Eyes of Project Management Information System and Project Team Members. Abasyn Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, L.; Xambre, A.R.; Figueiredo, J.; Alvelos, H. Analysis and Design of a Project Management Information System: Practical Case in a Consulting Company. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 100, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Purohit, A. Information management system in the livelihood project. Int. J. Res. Commer. IT Manag. 2016, 6, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Schwindt, C.; Zimmermann, J. Impact of Project Management Information Systems. In Handbook on Project Management and Scheduling; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 2, p. 1406. ISBN 9783319059150. [Google Scholar]

- PMBOK. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide); PMBOK: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781935589679. [Google Scholar]

- MeitY PMIS: Programme Management Information System. Available online: https://pmis.negd.gov.in (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Project Management for Development Organizations (PM4DEV). Project Information Management System; Project Management for Development Organizations: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Clemons, E.K.; Dewan, R.M.; Kauffman, R.J.; Weber, T.A. Understanding the Information-Based Transformation of Strategy and Society. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 34, 425–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NITI Aayog Monitoring Toolkits. Available online: https://dmeo.gov.in/monitoring/toolkits/dmeo (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Schmidt, T.D. Strategic Project Management Made Simple: Solution Tools for Leaders and Teams, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781119718185. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.K.F. Managing Project & Strategic Objectives with Logframe Analysis and the Logical Framework. PM World J. 2021, X, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, D.E.; Cooper, D.J. Seeing through the Logical Framework. Voluntas 2020, 31, 1239–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbutt, A.; Simister, N. The Logical Framework; Intrac for Civil Society: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Umhlaba Development Services. Introduction to Monitoring and Evaluation Using the Logical Framework Approach; Umhlaba Development Services: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DFID. Guidance on Using the Revised Logical Framework; DFID: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Project Design Manual A Step-by-Step Tool to Support the Development of Cooperatives and Other Forms of Self-Help Organization; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; ISBN 9789221241683. [Google Scholar]

- Purohit, A.; Chopra, D.G.; Dangwal, D.P.G. Determinants of Financial Wellness of Rural Households in the Hill Districts of Uttarakhand: An Empirical Approach. Indian J. Financ. Bank. 2022, 9, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiputra, I.G. The Influence of Financial Literacy, Financial Attitude and Locus of Control on Financial Satisfaction: Evidence From the Community in Jakarta. KnE Soc. Sci. 2021, 2021, 636–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD/INFE 2020 International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Murari, K. Managing Household Finance: An Assessment of Financial Knowledge and Behaviour of Rural Households. J. Rural Dev. 2019, 38, 706–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.; Maillet, S.; Koffi, V. Financial Knowledge, Financial Confidence and Learning Capacity on Financial Behavior: A Canadian Study. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2022, 8, 1996919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, A.; Dalziel, N. Mediation Effect of Financial Attitude on Financial Knowledge and Financial Behavior: The Case of University Students. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.C.; Yew, S.Y.; Wee, C.K. Financial Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour of Young Working Adults in Malaysia. Institutions Econ. 2018, 10, 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Raveendran, J.; Soren, J.; Ramanathan, V.; Sudharshan, R.; Mahalanabis, S.; Suresh, A.K.; Balaraman, V. Behavior Science Led Technology for Financial Wellness. CSI Trans. ICT 2021, 9, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraidah, Z.; Nasution, E.S. The Effect of Financial Literacy on Financial Behavior Moderated by Information Access. Proc. Int. Conf. Multidiciplinary Res. 2021, 4, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A.; Umar, A. The Relationship between Market Orientation, Human Resource Management, Adoption of Information Communication Technology, Performance of Small Medium Enterprises and Mediating Cash Management. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Rural Development and Entrepreneurship (ICORE), Kedah, Malaysia, 30 November–2 December 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Iramani, R.; Lutfi, L. An Integrated Model of Financial Well-Being: The Role of Financial Behavior. Accounting 2021, 7, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulaihati, S.; Widyastuti, U. Determinants of Consumer Financial Behavior: Evidence from Households in Indonesia. Accounting 2020, 6, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyastuti, U.; Sumiati, A.; Herlitah; Melati, I.S. Financial Education, Financial Literacy, and Financial Behaviour: What Does Really Matter? Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 2715–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, C.A.; Woodyard, A.S. Financial Knowledge and Best Practice Behavior. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2011, 22, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Huston, S.J. Measuring Financial Literacy. J. Consum. Aff. 2010, 44, 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha, F.; de New, J.P. Proposal of a Short Form Self-Reported Financial Wellbeing Scale for Inclusion in the 2026 Census. Aust. Popul. Stud. 2021, 5, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CFPB. CFPB Financial Well-Being Scale: Scale Development Technical Report; CFPB: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CFPB. Measuring Financial Well-Being: A Guide to Using the CFPB Financial Well-Being Scale; CFPB: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brüggen, E.C.; Hogreve, J.; Holmlund, M.; Kabadayi, S.; Löfgren, M. Financial Well-Being: A Conceptualization and Research Agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 79, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prawitz, A.D.; Cohart, J. Financial Management Competency, Financial Resources, Locus of Control, and Financial Wellness. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2016, 27, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemtsov, A.A.; Osipova, T.Y. Financial Wellbeing as a Type of Human Wellbeing: Theoretical Review. Eur. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. EpSBS 2016, 7, 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Falahati, L.; Sabri, M.F. An Exploratory Study of Personal Financial Wellbeing Determinants: Examining the Moderating Effect of Gender. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, R.S. Psychology (Revised Edition), 2nd ed.; Henry Holt & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; ISBN 8003742722. [Google Scholar]

- Olfat, M.; Ahmadi, S.; Shokouhyar, S.; Bazeli, S. Linking Organizational Members’ Social-Related Use of Enterprise Social Media (ESM) to Their Fashion Behaviors: The Social Learning and Stimulus-Organism-Response Theories. Corp. Commun. 2022, 27, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Feng, R. Social Media and Health: Emerging Trends and Future Directions for Research on Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandita, S.; Mishra, H.G.; Chib, S. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 Crises on Students through the Lens of Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) Model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopdar, P.K.; Balakrishnan, J. Consumers Response towards Mobile Commerce Applications: S-O-R Approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.K.; Jung, T. Exploring Consumer Behavior in Virtual Reality Tourism Using an Extended Stimulus-Organism-Response Model. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Shahid, S.; Rasool, A.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I.; Rather, R.A. Impact of Website Attributes on Customer Engagement in Banking: A Solicitation of Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1279–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqman, A.; Cao, X.; Ali, A.; Masood, A.; Yu, L. Empirical Investigation of Facebook Discontinues Usage Intentions Based on SOR Paradigm. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, S.; Sai Vijay, T.; Parsad, C. Effects of Online Shopping Values and Website Cues on Purchase Behaviour: A Study Using S-O-R Framework. Vikalpa—J. Decis. Makers 2017, 42, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbonlahor, E.; Oasgiede, I.F. Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) Interaction Effects of the Sign Learning Theory in Achieving Motor Outcomes. J. Lang. Technol. Entrep. AFRICA 2017, 8, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Yue, X.; Ye, Y.; Peng, M.Y.P. Understanding the Impact of the Psychological Cognitive Process on Student Learning Satisfaction: Combination of the Social Cognitive Career Theory and SOR Model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PIB Categorisation of Farmers. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=188051 (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- ICAR. Evaluation of Successful Interventions under the Integrated Livelihoods Support Project (ILSP) of Uttarakhand and the Lessons for Out-Scaling; Central Project Coordination Unit (CPCU): New Delhi, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CPCU. ILSP: Annual Progress Report—2020–21; Integrated Livelihood Support Project (ILSP): Dehradun, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CPCU. ILSP: Annual Progress Report—2017–18; Integrated Livelihood Support Project (ILSP): Dehradun, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UGVS. Case Studies—Towards Prosperity; Integrated Livelihood Support Project (ILSP): Dehradun, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, K. Cooperative Movement and Its Emerging Scenario in India. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 3799–3802. [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo, A.K.; Meher, S.K.; Panda, T.C.; Sahu, S.; Begum, R.; Barik, N.C. Critical Review on Cooperative Societies in Agricultural Development in India. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2020, 39, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolakis, G.; Van Dijk, G. Cooperative Organizations and Members’ Role: A New Perspective; CIRIEC No 2018/04; CIRIEC International: Liège, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- PIB Cooperatives Should Play Significant Role in the Implementation of Development Schemes. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=123141 (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- COOP What Is a Cooperative? Available online: https://www.ica.coop/en/cooperatives/what-is-a-cooperative (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- UNDP. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goal (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- UNDP. The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 9789211264425. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, F.; Anwar, A.; Hsu, C.C.; Sharif, A.; Razzaq, A.; Sinha, A. The Role of Information and Communication Technology in Encountering Environmental Degradation: Proposing an SDG Framework for the BRICS Countries. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyebu, U.F.; Emmanuel, D.U.; Ali, G.J. The Role of ICT in Sustainable Development Goal (SDG). West Afr. J. Ind. Acad. Res. 2019, 20, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, S. Perspectives on Development: Why Does Studying Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D) Matter? Inf. Technol. Dev. 2019, 25, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, S.; Vatta, L. ICT: A Deed for Sustainable Development Goals. J. Natl. Dev. 2018, 31, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, F.J.; Pont, A. ICT for Promoting Human Development and Protecting the Environment. IFIP Int. Fed. Inf. Process. 2016, 2, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PaySe. Digitizing SHG Transactions—A Case of PaySe; PaySe: Noida, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qureshi, S. Why Data Matters for Development? Exploring Data Justice, Micro-Entrepreneurship, Mobile Money and Financial Inclusion. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2020, 26, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success: A Ten-Year Update. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Systems: The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). Int. J. Man. Mach. Stud. 1993, 38, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannidis, S. Theoryhub Book; Theory Hub: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2022; ISBN 9781739604400. Available online: https://open.ncl.ac.uk (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information Systems Success: The Quest for the Dependent Variable. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1992, 3, 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Information Systems Success Measurement. Found. Trends Inf. Syst. 2016, 2, 1–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistiyani, E.; Tyas, S.H.Y. What Is the Measurement of the the IT Success? Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 197, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garomssa, S.D.; Kannan, R.; Chai, I. Updated DeLone and McLean IS Success Model and Commercial Open Source Software (COSS) Company Success. In Proceedings of the 10th Knowledge Management International Conference (KMICe2021), Putrajaya, Malaysia, 1 February 2021; pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Alketbi, S.; Akmal, S.; Al-Shami, S.S.A.; Hamid, R.A. Conceptual Framework: The Role of Cognitive Absorption in Delone and Mclean Success Model in Online Learning in United Arab Emirates. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, N.W.S.C.; Suprasto, H.B.; Bagus, A.A.N.; Dwija Putri, I.G.A.M.A. Putri Implementation of the Tri Hita Karana Culture in Delone and Mclean Models to Assess The Success of Using Accounting Information Systems. J. Econ. Financ. Manag. Stud. 2021, 4, 2082–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Nagpal, P.; Lim, H.S.; Dutil, L.; Lee, R.; Kim, Y. A Variation of the DeLone and McLean Model for Collaborative Commerce Services: A Structural Equation Model. J. Int. Technol. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Le, Q.B.; Nguyen, M.D.; Bui, V.C.; Dang, T.M.H. The Determinants of Management Information Systems Effectiveness in Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaineldeen, S.; Hongbo, L.; Koffi, A.L. Review of The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success’ Background and It’s an Application in the Education Setting, and Association Linking with Technology Acceptance Model. Int. J. Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.Y.; Jeon, Y.J.J. The Difference of User Satisfaction and Net Benefit of a Mobile Learning Management System According to Self-Directed Learning: An Investigation of Cyber University Students in Hospitality. Sustainbility 2020, 12, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, G.; Madan, P.; Jaisingh, P.; Bhaskar, P. Effectiveness of E-Learning Portal from Students’ Perspective: A Structural Equation Model (SEM) Approach. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2019, 16, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamary, Y.H.S. Measuring Information Systems Success in Yemen: Potential of Delone and Mcleans Model. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2019, 8, 793–799. [Google Scholar]

- Adya, M.; Wang, W.; Donovan, E.; Indira, G.R. A Cloud Update of the DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems. J. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2018, XXIX, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi, Z.; Esmaelzadeh-Saeieh, S.; Lotfi, R.; Baradaran Eftekhari, M.; Akbari Kamrani, M.; Mehdizadeh Tourzani, Z.; Salehi, K. The Evaluation of a Virtual Education System Based on the DeLone and McLean Model: A Path Analysis. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedera, D.; Eden, R.; McLean, E.R. Are We There yet? A Step Closer to Theorizing Information Systems Success. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2013): Reshaping Society Through Information Systems Design, Milan, Italy, 15–18 December 2013; Volume 1, pp. 499–519. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Rashid, U.; Nasuredin, J.; Hamawandy, N.; Bewani, H.; Jamil, D. The Effect of Delone and Mclean’s Information System Success Model on The Job Performance of Accounting Managers in Iraqi Banks. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2021, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seliana, N.; Suroso, A.I.; Yuliati, L.N. Evaluation of E-Learning Implementation in the University Using Delone and Mclean Success Model. J. Apl. Manaj. 2020, 18, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, Y.; Prasetyo, A. Assessing Information Systems Success: A Respecification of the DeLone and McLean Model to Integrating the Perceived Quality. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2018, 16, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, C.; Bayona, S. IT Projects Success Factors: A Literature Review. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Proj. Manag. 2020, 8, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Ahn, J.C.; Jung, S.H.; Kim, J.H. Communities of Practice and Knowledge Management Systems: Effects on Knowledge Management Activities and Innovation Performance. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2020, 18, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.Z.; Kar, A.K.; Janssen, M.F.W.H.A. Understanding the impact of digital service failure on users: Integrating Tan’s failure and DeLone and McLean’s success model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coiera, E. Assessing Technology Success and Failure Using Information Value Chain Theory. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 263, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. Measuring E-Commerce Success: Applying the DeLone and McLean Information Systems Success Model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2004, 9, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardianti; Hidayatullah, S.; Respati, H. Implementation of the DeLone and McLean information system success models for information systems based on social media. Int. J. Creat. Res. Throughts 2021, 9, 4361–4368. [Google Scholar]

- Paudel, S.; Kumar, V. Critical Success Factors of Information Technology Outsourcing for Emerging Markets. J. Comput. Sci. 2021, 17, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riasti, B.K.; Nugroho, A. Analysis of the Success of Student Monitoring Information System Implementation Using DeLone and McLean Model. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1339, 012063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Doll, W.; Deng, X.; Williams, M. The Impact of Organisational Support, Technical Support, and Self-Efficacy on Faculty Perceived Benefits of Using Learning Management System. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, S.H.; Ali, M.B.; Rosli, M.S. The Influences of Technical Support, Self Efficacy and Instructional Design on the Usage and Acceptance of LMS: A Comprehensive Review. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 15, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Petter, S.; Delone, W.; McLean, E.R. Information Systems Success: The Quest for the Independent Variables. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2013, 29, 7–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, N.W.W.; Yanuartha, W.; Yani, M.; Dewa, S.R. Evaluation of E-Learning Implementation During the COVID-19 with the DeLone and McLean Models. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. 2021, 4, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyanto, D.; Dewi, A.A.; Hasibuan, H.T.; Paramadani, R.B. The Success of Information Systems and Sustainable Information Society: Measuring the Implementation of a Village Financial System. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, M.; Nistala, N. IFFCO: Staying on Top of the Cooperatives. In Catalysing Sustainable Development Through Producers Collectives; Tripathy, K.K., Wadkar, S.K., Singh, A., Eds.; Notion Press: Chennai, India, 2021; pp. 255–284. ISBN 9781639403844. [Google Scholar]

- Tambo, J.A.; Aliamo, C.; Davis, T.; Mugambi, I.; Romney, D.; Onyango, D.O.; Kansiime, M.; Alokit, C.; Byantwale, S.T. The Impact of ICT-Enabled Extension Campaign on Farmers’ Knowledge and Management of Fall Armyworm in Uganda. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFAD. 10 Ways in Which ICTs Can Transform the Lives of Rural Women. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/latest/story/asset/40232867 (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Siochrú, S.Ó. Empowering Communities through ICT Cooperative Enterprises: The Case of India. In Proceedings of the Development in the Information Society: Exploring a Social Policy Framework, Bangalore, India, 18–20 January 2007; pp. 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- NIRDPR. Impact Evaluation of Financial Inclusion Programmes of UPASaC in Uttarakhand; National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj: Hyderabad, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Walsham, G. ICT4D Research: Reflections on History and Future Agenda. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2017, 23, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.P.; Arvin, M.B.; Nair, M.S.; Hall, J.H.; Bennett, S.E. Sustainable Economic Development in India: The Dynamics between Financial Inclusion, ICT Development, and Economic Growth. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 169, 120758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.A.; Alam, M.M.D.; Taghizadeh, S.K. Do Mobile Financial Services Ensure the Subjective Well-Being of Micro-Entrepreneurs? An Investigation Applying UTAUT2 Model. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2020, 26, 421–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, R.; Bruneau, C. Microfinance, Financial Inclusion and ICT: Implications for Poverty and Inequality. Technol. Soc. 2019, 59, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapukeni, A.F. Financial Inclusion and the Impact of ICT: An Overview. Am. J. Econ. 2015, 5, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Word Bank Financial Inclusion Overview. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview#1 (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Peng, C.; Ma, B.; Zhang, C. Poverty Alleviation through E-Commerce: Village Involvement and Demonstration Policies in Rural China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RBI. Master Circular—Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana—National Rural Livelihoods Mission (DAY-NRLM); RBI/2019-2; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Hatakka, M.; Sahay, S.; Andersson, A. Conceptualizing Development in Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D). Inf. Technol. Dev. 2018, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshubiri, F.; Jamil, S.A.; Elheddad, M. The Impact of ICT on Financial Development: Empirical Evidence from the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NABARD. Master Circular on Self Help Group-Bank Linkage Programme; NABARD: Mumbai, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CPCU. ILSP: Annual Progress Report—2019–20; Integrated Livelihood Support Project (ILSP): Dehradun, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CPCU. ILSP: Annual Progress Report—2018–19; Integrated Livelihood Support Project (ILSP): Dehradun, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- CPCU. ILSP: Annual Progress Report—2013–14; Integrated Livelihood Support Project (ILSP): Dehradun, India, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, D.; Hanspal, T.; Liao, Y.; Liu, Y. Financial Literacy and Self-Control in FinTech: Evidence from a Field Experiment on Online Consumer Borrowing; SAFE Working Paper No. 273; Leibniz Institute for Financial Research SAFE: Frankfurt, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fazli Sabri, M.; Reza, T.S.; Wijekoon, R. Financial Management, Savings and Investment Behavior and Financial Well-Being of Working Women in the Public Sector. Maj. Ilm. Bijak 2020, 17, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyegera, G.K.; Matsumoto, T. ICT for Financial Access: Mobile Money and the Financial Behavior of Rural Households in Uganda. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2018, 22, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despard, M.R.; Friedline, T.; Martin-West, S. Why Do Households Lack Emergency Savings? The Role of Financial Capability. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2020, 41, 542–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaisina, S.; Kaidarova, L. Financial Literacy of Rural Population as a Determinant of Saving Behavior in Kazakhstan. Rural Sustain. Res. 2017, 38, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.N.; Rózsa, Z.; Belás, J.; Belásová, Ľ. The Effects of Perceived and Actual Financial Knowledge on Regular Personal Savings: Case of Vietnam. J. Int. Stud. 2017, 10, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulaj, E.; Dragusha, B.; Lulaj, D.; Rustaj, V.; Gashi, A. Households Savings and Financial Behavior in Relation To the Ability To Handle Financial Emergencies: Case Study of Kosovo. Acta Sci. Pol. Oeconomia 2021, 20, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Household Savings. OECD Factbook 2015–2016: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016; pp. 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, R.; Gilligan, M.J.; Rieger, M. Self-Help Groups, Savings and Social Capital: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Cambodia. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2020, 180, 174–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhela, S.; Prakash, A. Saving Preferences and Financial Literacy of Self Help Group Members: A Study of Uttar Pradesh. Manthan J. Commer. Manag. 2018, 4, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.; Vijayalakshmi, C.; Raghuraman, S. Role of Voluntary Savings in SHG/SHG Members: An Analysis in Tamil Nadu & Karnataka; NABARD: Mumbai, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, Y.; Andersen, P. Rural Livelihood Diversification and Household Well-Being: Insights from Humla, Nepal. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 44, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Jose, L.; Iturralde, T.; Maseda, A. The Influence of Information Communications Technology (ICT) on Cash Management and Financial Department Performance: An Explanatory Model. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2009, 26, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meenatchi, M.E.; Ponnudurai, D.S.A. A Study on Factor Influencing SHG Members to Start Enterprises and Problems Encountered by the SHGs Members in Their Enterprises in Thoothukudi District. Hist. Res. J. 2019, 5, 2828–2838. [Google Scholar]

- Prashar, M.; Chahal, B.P.S. Micro-Savings, Micro-Finance and Selfempowerment—Analysis of Rural Women SHGs of Punjab. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst. 2019, 11, 1354–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Samishetti, B.; Anusha, K. Financial Management of Self Help Groups in the Warangal Rural District. Eur. J. Mol. Clin. Med. 2020, 7, 866–876. [Google Scholar]

- Chavali, K.; Raj, P.M.; Ahmed, R. Does Financial Behavior Influence Financial Well-Being? J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömbäck, C.; Lind, T.; Skagerlund, K.; Västfjäll, D.; Tinghög, G. Does Self-Control Predict Financial Behavior and Financial Well-Being? J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2017, 14, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, R.; Manohar, V. Financial Literacy—A Determinant of Investment in Health Insurance. Int. J. Commer. 2020, 8, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IGI-Global. What Is Financial Attitudes. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/financial-literacy/58683 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Talwar, M.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Tripathy, N.; Dhir, A. Has Financial Attitude Impacted the Trading Activity of Retail Investors during the COVID-19 Pandemic? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, K.; Dua, S.; Yadav, M. Association of Financial Attitude, Financial Behaviour and Financial Knowledge Towards Financial Literacy: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2019, 8, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.S.; Singh, K.M. Measurement of Attitudes of Rural Poor Towards SHGs in Bihar, India. SSRN Electron. J. 2012, March, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strumpel, B. Economic Means for Human Needs: Social Indicators of Well-Being and Discontent; U Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, N.M.; Thomas Garman, E.; Garman, E.T. Testing a Conceptual Model of Financial Well-Being. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 1993, 4, 135–164. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, S.; Grable, J.E. An Exploratory Framework of the Determinants of Financial Satisfaction. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2004, 25, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodyard, A. Measuring Financial Wellness. Consum. Interes. Annu. 2013, 59, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kempson, E.; Finney, A.; Poppe, C. Financial Well-Being A Conceptual Model and Preliminary Analysis. SIFO Consumption Research Norway: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Predergast, S.; Blackmore, D.; Kempson, E. Financial Wellbeing—A Survey of Adults in New Zealand; ANZ Banking Group Limited: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reserve Bank of India. National Strategy for Financial Education 2020–2025; Reserve Bank of India: Mumbai, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- PwC. PwC’s 9th Annual Employee Financial Wellness Survey; PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Potrich, A.C.G.; Vieira, K.M.; Mendes-Da-Silva, W. Development of a Financial Literacy Model for University Students. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besri, A.A.O. Pengaruh Financial Attitude, Financial Knowledge Dan Locus of Control Terhadap Financial Management Behavior Mahasiswa S-1 Fakultas Ekonomi Universitas Islam Indonesia Yogyakarta; Universitas Islam Indonesia: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2018; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ponchio, M.C.; Cordeiro, R.A.; Gonçalves, V.N. Personal Factors as Antecedents of Perceived Financial Well-Being: Evidence from Brazil. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1004–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, A.I. Validation of the Delone and Mclean Information Systems Success Model. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2017, 23, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.J.; Kim, K.T. The Able Worry More? Debt Delinquency, Financial Capability, and Financial Stress. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2022, 43, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutti, R.K.P. An Analysis of Literacy in Finance among the Students of Postgraduate Management Studies in Hyderabad. Int. J. Mod. Agric. 2020, 9, 893–903. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, B.; Peng, M.H.; Chen, C.C.; Sun, S.L. Interpreting Usability Factors Predicting Sustainable Adoption of Cloud-Based e-Learning Environment during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainbility 2021, 13, 9329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongmak, M. A Model for Enhancing Employees’ Lifelong Learning Intention Online. Learn. Motiv. 2021, 75, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xiong, J.; Yan, J.; Wang, Y. Perceived Quality of Traceability Information and Its Effect on Purchase Intention towards Organic Food. J. Mark. Manag. 2021, 37, 1267–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldholay, A.H.; Isaac, O.; Abdullah, Z.; Ramayah, T. The Role of Transformational Leadership as a Mediating Variable in DeLone and McLean Information System Success Model: The Context of Online Learning Usage in Yemen. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1421–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalloul, M.H.M.; Ibrahim, Z.B.; Urus, S.T. The Association Between the Success of Information Systems and Crises Management (A Theoretical View and Proposed Framework). Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božič, K.; Dimovski, V. The Relationship between Business Intelligence and Analytics Use and Organizational Absorptive Capacity: Applying the DeLone & Mclean Information Systems Success Model. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2020, 22, 191–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coşkuner, S. Understanding Factors Affecting Financial Satisfaction: The Influence of Financial Behavior, Financial Knowledge and Demographics. Imp. J. Interdiscip. Res. 2016, 2, 377–385. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 23 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 14th ed.; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781138491045. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, M.W. Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. J. Black Psychol. 2018, 44, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baistaman, J.; Awang, Z.; Afthanorhan, A.; Zulkifli Abdul Rahim, M. Developing and Validating the Measurement Model for Financial Literacy Construct Using Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2020, 8, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, Y.; Jusoff, K.; Ibrahim, Y.; Awang, Z. The Influence of Green Practices by Non-Green Hotels on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in Hotel and Tourism Industry. Int. J. Green Econ. 2017, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, Z. Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS Graphic; Penerbit Universiti Teknologi MARA: Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2012; ISBN 9789673634187. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781609182304. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin, J. CFA: Model Fit Analysis. Available online: http://statwiki.gaskination.com/index.php?title=CFA#Model_Fit (accessed on 4 July 2021).

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A Reliablity Coefficient for Maximum Likelihood Factor Analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 421–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, J.; Shirkey, G.; John, R.; Wu, S.R.; Park, H.; Shao, C. Applications of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Ecological Studies: An Updated Review. Ecol. Process. 2016, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, A.; Dillon, W.R. A Simulation Study to Investigate the Use of Cutoff Values for Assessing Model Fit in Covariance Structure Models. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakshit, S.; Mondal, S.; Islam, N.; Jasimuddin, S.; Zhang, Z. Social Media and the New Product Development during COVID-19: An Integrated Model for SMEs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 170, 120869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.H.; Wu, Y.S.; Cheng, C.S.; Kuo, M.H.; Chang, Y.T.; Hu, F.K.; Sun, C.A.; Chang, C.W.; Chan, T.C.; Chen, C.W.; et al. A Technology Acceptance Model for Deploying Masks to Combat the COVID-19 Pandemic in Taiwan (My Health Bank): Web-Based Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.-I. Comparisons of Competing Models between Attitudinal Loyalty and Behavioral Loyalty. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, H.; Homburg, C. Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing and Consumer Research: A Review. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 13, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, W.J.; Xia, W.; Torkzadeh, G. A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the End-User Computing Satisfaction Instrument. MIS Q. 1994, 18, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kim, C.Y.; Lee, E.H.; Yoo, J.W. Relationship between Sustainable Management Activities and Financial Performance: Mediating Effects of Non-Financial Performance and Moderating Effects of Institutional Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archimi, C.S.; Reynaud, E.; Yasin, H.M.; Bhatti, Z.A. How Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility Affects Employee Cynicism: The Mediating Role of Organizational Trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781483377445. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, A.B.I.; Mendoza, N.B. Measuring Hope during the COVID-19 Outbreak in the Philippines: Development and Validation of the State Locus-of-Hope Scale Short Form in Filipino. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 5698–5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif Nia, H.; She, L.; Rasiah, R.; Khoshnavay Fomani, F.; Kaveh, O.; Pahlevan Sharif, S.; Hosseini, L. Psychometrics of Persian Version of the Ageism Survey Among an Iranian Older Adult Population During COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Public Heal. 2021, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- She, L.; Ma, L.; Khoshnavay Fomani, F. The Consideration of Future Consequences Scale Among Malaysian Young Adults: A Psychometric Evaluation. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 770609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uslu, A.; Alagöz, G.; Güneş, E. Socio-Cultural, Economic, and Environmental Effects of Tourism from the Point of View of the Local Community. J. Tour. Serv. 2020, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, G.R.; Mueller, R.O. Rethinking Construct Reliability within Latent Variable Systems. In Structural Equation Modeling: Present and Future: A Festschrift in Honor of Karl Jöreskog; Cudeck, R., du Toit, S., Srbom, D., Eds.; Scientific Software International: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 2001; pp. 195–216. ISBN 9780894980497. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; J.Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Mat, W.R.; Kim, H.J.; Abdul Manaf, A.A.; Phang Ing, G.; Abdul Adis, A.A. Young Malaysian Consumers’ Attitude and Intention to Imitate Korean Celebrity Endorsements. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2019, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, X.J.; bt Mohd Radzol, A.R.; Cheah, J.-H.; Wong, M.W. The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Purchase Intention and the Mediation Effect of Customer Attitude. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2017, 7, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Hamid, M.R.; Sami, W.; Mohmad Sidek, M.H. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker Criterion versus HTMT Criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge Management: An Organizational Capabilities Perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, E.; Schuberth, F.; Henseler, J. HTMT2–an Improved Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Structural Equation Modeling. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2021, 121, 2637–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, H. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 0805802835. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling, 1st ed.; University of Akron: Akron, OH, USA, 1992; ISBN 0962262846. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. ISBN 0-8058-2677-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Fangwei, Z.; Siddiqi, A.F.; Ali, Z.; Shabbir, M.S. Structural Equation Model for Evaluating Factors Affecting Quality of Social Infrastructure Projects. Sustainbility 2018, 10, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhendawi, K.M.; Baharudin, A.S. The Assessment of Information System Effectiveness in E-Learning, E-Commerce and E-Government Contexts: A Critical Review of the Literature. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2017, 95, 4897–4912. [Google Scholar]

- Shaharuddin, N.S.; Zain, Z.M.; Ahmad, S.F.S. Financial Planning Determinants Among Working Adults During COVID 19 Pandemic. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2021, 1, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marime, N.; Magweva, R.; Dzapasi, F.D. Demographic Determinants of Financial Literacy in the Masvingo Province of Zimbabwe. PM World J. 2020, IX, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- GOI Rurban Cluster. Available online: https://rurban.gov.in/index.php/public_home/rurban_cluster#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Simon, D. Peri-Urbanization. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Futures; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-3-030-51812-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, R.; Wescoat, J.L. Visualizing Peri-Urban and Rurban Water Conditions in Pune District, Maharashtra, India. Geoforum 2019, 102, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Rahman, A. Urbanising the Rural: Reflections on India’s National Rurban Mission. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2018, 5, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Variables | References |

|---|---|---|

| PMIS Quality | Easy to Operate, System functionality, Representation of Data, Usability | [72,80,81,84,88,90,91,92,95,96,97,104,105,109,164] |

| Information Quality | Accuracy, Easy-to-understand, Evidence, Decision Support | |

| Service Quality | Training, Assurance | |

| Net Benefits of PMIS | Implementation, Evaluation, Gap Analysis, Save Time, Knowledge Increase | |

| Cash Management | Budget Management, Payment of Utility Bills, Purchase Behavior | [19,20,21,31,34,35,158,165,166] |

| Savings Behavior | Savings Perception, Regular Savings | |

| Risk–Credit Management | Life Insurance, Health Insurance, Crop Insurance, Cattle Insurance, Loan (Kisan Credit Card) | |

| Financial Attitude | Expenditure Attitude, Attitude towards Income-Generating Activities | |

| Financial Wellness | Income, Savings, Living Standards |

| Authors | Theme/Domain | Summary of Model |

|---|---|---|

| [82] | The success of the IT Project | IT system projects are affected by stakeholder acceptance, product quality, organization benefit, and technical project. |

| [171] | ISs-CM model | Crisis Management (CM) effectiveness depends upon system quality, information quality, service quality, system use, and user satisfaction. At the same time, crisis management refers to pre-crisis, during, and post-crisis. |

| [110] | Village Financial System | The study uses information quality, system quality, service quality, use, user satisfaction, net benefits, trust in government organizations, trust in technology, and sustainable information society to measure the village financial information system success. |

| [84] | Online learning system | Technological characteristics of the system depend upon system quality, knowledge quality, and service quality. Actual usage and user satisfaction mediate the performance impact of the online learning system. Cognitive absorption moderates the performance impact. |

| [85] | The success of accounting information system (AIS) | Tri Hita Karana culture positively impacts system quality, information quality, service quality, use of the AIS, and user satisfaction. The use of the AIS and user satisfaction impact the net benefits of the AIS. |

| [167] | Adoption of Cloud-based E-learning Environment | The study examined the sustainable adoption of cloud-based e-learning. The researchers measured subjective well-being through system quality, perceived service quality, perceived closeness, and online course quality. Attitudinal readiness is measured through peer referent, perceived usefulness, ease of use, and perceived ubiquity. The e-learning adoption intention depends upon attitudinal readiness, self-efficacy, and subjective well-being. |

| [168] | Intention to adopt Lifelong Learning (LLL) of employees | The study examined the intention to adopt LLP of employees through gamification, self-determination, and online learning readiness. An organization’s online learning readiness is measured by resource, education, and environment readiness. Self-determination is measured by autonomy, relatedness, and competence. |

| [169] | Perceived quality of traceability information (PQTI) | The paper examined the PQTI and its effect on purchase intention towards organic food. The PQTI is measured through product diagnosticity, informativeness, and trustworthiness. The PQTI impacts perceived uncertainty and purchase intention, where the importance of product information moderates purchase intention. |

| [87] | MIS effectiveness in small and medium enterprises | Information Quality is related to organizational characteristics, management knowledge, commitment, and user involvement. MIS effectiveness is correlated with information quality, organizational characteristics, management knowledge, commitment, and user involvement. |

| [172] | Firm’s absorptive capacity for knowledge creation | System quality, information quality, degree of use, and nature of use impact business intelligence and analytics (BI&A), significantly impacting absorptive capacity. |

| [90] | Effectiveness of e-learning portal | E-learning systems are measured through system quality, information quality, and service quality. E-learning effectiveness is measured through user satisfaction and net benefits. |

| Construct | Items | Factor Loading (without CLF) (above 0.5) | Composite Reliability (above 0.7) | AVE (above 0.5) | MSV (Less than AVE) | ASV (Less than AVE) | MaxR(H) (above CR) | Cronbach’s Alpha (0.7) | Factor Loading with CLF (above 0.5) | Difference (without CLF–with CLF) (<0.2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMIS Quality | SysQ01 | 0.813 | 0.944 | 0.771 | 0.417 | 0.197 | 0.951 | 0.941 | 0.786 | 0.027 |

| SysQ02 | 0.855 | 0.828 | 0.027 | |||||||

| SysQ03 | 0.934 | 0.907 | 0.027 | |||||||

| SysQ04 | 0.899 | 0.873 | 0.026 | |||||||

| SysQ05 | 0.884 | 0.854 | 0.030 | |||||||

| Information Quality | InfoQ01 | 0.883 | 0.928 | 0.763 | 0.342 | 0.127 | 0.931 | 0.924 | 0.844 | 0.039 |

| InfoQ02 | 0.900 | 0.866 | 0.034 | |||||||

| InfoQ03 | 0.887 | 0.847 | 0.040 | |||||||

| InfoQ04 | 0.821 | 0.789 | 0.032 | |||||||

| Service Quality | SerQ01 | 0.834 | 0.925 | 0.805 | 0.394 | 0.187 | 0.936 | 0.921 | 0.806 | 0.028 |

| SerQ02 | 0.935 | 0.909 | 0.026 | |||||||

| SerQ03 | 0.919 | 0.893 | 0.026 | |||||||

| Net Benefits | NetBen01 | 0.825 | 0.874 | 0.539 | 0.417 | 0.211 | 0.885 | 0.872 | 0.778 | 0.047 |

| NetBen02 | 0.794 | 0.733 | 0.061 | |||||||

| NetBen03 | 0.701 | 0.647 | 0.054 | |||||||

| NetBen04 | 0.678 | 0.633 | 0.045 | |||||||

| NetBen05 | 0.766 | 0.702 | 0.064 | |||||||

| NetBen06 | 0.620 | 0.508 | 0.112 | |||||||

| Savings Behavior | FB2S1 | 0.929 | 0.841 | 0.643 | 0.461 | 0.205 | 0.900 | 0.831 | 0.883 | 0.046 |

| FB2S2 | 0.816 | 0.760 | 0.056 | |||||||

| FB2S3 | 0.632 | 0.551 | 0.081 | |||||||

| Cash Management | FB1CM1 | 0.806 | 0.872 | 0.631 | 0.461 | 0.197 | 0.874 | 0.871 | 0.774 | 0.032 |

| FB1CM2 | 0.768 | 0.720 | 0.048 | |||||||

| FB1CM3 | 0.824 | 0.793 | 0.031 | |||||||

| FB1CM4 | 0.777 | 0.736 | 0.041 | |||||||

| Risk-Credit Management | FB3RCM1 | 0.669 | 0.865 | 0.572 | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.931 | 0.863 | 0.666 | 0.003 |

| FB3RCM2 | 0.565 | 0.560 | 0.005 | |||||||

| FB3RCM3 | 0.915 | 0.911 | 0.004 | |||||||

| FB3RCM4 | 0.930 | 0.928 | 0.002 | |||||||

| FB3RCM5 | 0.626 | 0.620 | 0.006 | |||||||

| Financial Attitude | FL3A1 | 0.820 | 0.869 | 0.625 | 0.162 | 0.059 | 0.874 | 0.864 | 0.787 | 0.033 |

| FL3A2 | 0.797 | 0.767 | 0.030 | |||||||

| FL3A3 | 0.825 | 0.778 | 0.047 | |||||||

| FL3A4 | 0.714 | 0.660 | 0.054 | |||||||

| Financial Wellness | FW1 | 0.927 | 0.940 | 0.840 | 0.410 | 0.180 | 0.955 | 0.935 | 0.917 | 0.010 |

| FW2 | 0.961 | 0.951 | 0.010 | |||||||

| FW3 | 0.859 | 0.841 | 0.018 |

| Financial Attitude | PMIS Quality | Information Quality | Service Quality | Net Benefits | Savings Behavior | Cash Management | Risk-Credit Management | Financial Wellness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Attitude | 0.790 | ||||||||

| PMIS Quality | 0.071 | 0.878 | |||||||

| Information Quality | 0.025 | 0.585 | 0.873 | ||||||

| Service Quality | 0.122 | 0.628 | 0.556 | 0.897 | |||||

| Net Benefits | 0.180 | 0.646 | 0.478 | 0.566 | 0.734 | ||||

| Savings Behavior | 0.368 | 0.398 | 0.234 | 0.408 | 0.492 | 0.802 | |||

| Cash Management | 0.348 | 0.389 | 0.211 | 0.397 | 0.486 | 0.679 | 0.794 | ||

| Risk–Credit Management | −0.007 | −0.112 | 0.118 | −0.037 | −0.039 | 0.121 | 0.048 | 0.756 | |

| Financial Wellness | 0.402 | 0.308 | 0.149 | 0.366 | 0.461 | 0.640 | 0.637 | 0.029 | 0.917 |

| PMIS Quality | Information Quality | Service Quality | Net Benefits | Savings Behavior | Cash Management | Risk-Credit Management | Financial Attitude | Financial Wellness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMIS Quality | |||||||||

| Information Quality | 0.594 | ||||||||

| Service Quality | 0.653 | 0.326 | |||||||

| Net Benefits | 0.657 | 0.481 | 0.574 | ||||||

| Savings Behavior | 0.423 | 0.226 | 0.437 | 0.502 | |||||

| Cash Management | 0.389 | 0.215 | 0.392 | 0.497 | 0.703 | ||||

| Risk-Credit Management | −0.100 | 0.141 | 0.007 | −0.005 | 0.109 | 0.093 | |||

| Financial Attitude | 0.076 | 0.026 | 0.121 | 0.190 | 0.372 | 0.357 | 0.001 | ||

| Financial Wellness | 0.066 | 0.152 | 0.368 | 0.470 | 0.657 | 0.662 | 0.090 | 0.415 |

| PMIS Quality | Information Quality | Service Quality | Net Benefits | Savings Behavior | Cash Management | Risk-Credit Management | Financial Attitude | Financial Wellness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMIS Quality | |||||||||

| Information Quality | 0.594 | ||||||||

| Service Quality | 0.653 | 0.587 | |||||||

| Net Benefits | 0.656 | 0.470 | 0.570 | ||||||

| Savings Behavior | 0.424 | 0.218 | 0.439 | 0.490 | |||||

| Cash Management | 0.384 | 0.211 | 0.387 | 0.491 | 0.699 | ||||

| Risk-Credit Management | 0.087 | 0.139 | −0.081 | 0.060 | −0.157 | 0.064 | |||

| Financial Attitude | 0.073 | 0.026 | 0.120 | 0.176 | 0.368 | 0.352 | 0.000 | ||

| Financial Wellness | 0.317 | 0.149 | 0.367 | 0.467 | 0.653 | 0.657 | −0.063 | 0.408 |

| Constructs | R-Square | [211] | [212] | [213] | [215] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net Benefits | 0.57 | Substantial | Adequate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Financial Behavior | 0.49 | Substantial | Adequate | Moderate | Weak |

| Financial Attitude | 0.23 | Moderate | Adequate | Weak | Weak |

| Financial Wellness | 0.63 | Substantial | Adequate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Chi-Square/df | GFI | AGFI | SRMR | NFI | PNFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | PGFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Risk-Credit Management | 2.855 | 0.865 | 0.847 | 0.084 | 0.902 | 0.839 | 0.934 | 0.929 | 0.934 | 0.763 | 0.054 |

| Without Risk-Credit Management | 2.620 | 0.893 | 0.876 | 0.069 | 0.925 | 0.849 | 0.952 | 0.948 | 0.952 | 0.769 | 0.051 |

| Hypothesis | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Acceptance/Rejection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a. PMIS quality is significantly important for an effective PMIS. | |||||

| PMIS Quality <--- PMIS | 0.844 | 0.112 | 13.946 | *** | Accepted |

| H1b. Information quality is significantly important for an effective PMIS. | |||||

| Information Quality <--- PMIS | 0.686 | 0.046 | 13.946 | *** | Accepted |

| H1c. Service quality is significantly important for an effective PMIS. | |||||

| Service Quality <--- PMIS | 0.764 | 0.105 | 13.501 | *** | Accepted |

| H2. An effective PMIS has a significant impact on the net benefits of PMIS. | |||||

| Net Benefits <--- PMIS | 0.756 | 0.056 | 12.999 | *** | Accepted |

| H3. Net benefits of PMIS has a significant impact on financial behavior. | |||||

| Financial Behavior <--- Net Benefits | 0.700 | 0.055 | 12.804 | *** | Accepted |

| H4a. Savings behavior is significantly important for financial behavior. | |||||

| Savings Behavior <--- Financial Behavior | 0.867 | 0.044 | 18.453 | *** | Accepted |

| H4b. Cash Management is significantly important for financial behavior. | |||||

| Cash Management <--- Financial Behavior | 0.824 | 0.058 | 17.575 | *** | Accepted |

| H4c. Risk-credit management is significantly important for financial behavior. | |||||

| Risk-Credit Management <--- Financial Behavior | 0.076 | 0.117 | 1.688 | 0.092 | Rejected |

| H5. Net benefits of PMIS has a significant impact on financial attitude. | |||||

| Financial Attitude <--- Net Benefits | 0.481 | 0.067 | 4.666 | *** | Accepted |

| H6. Financial behavior has a significant impact on financial wellness | |||||

| Financial Wellness <--- Financial Behavior | 0.704 | 0.1 | 16.86 | *** | Accepted |

| H7. Financial attitude has a significant impact on financial wellness. | |||||

| Financial Wellness <--- Financial Attitude | 0.189 | 0.055 | 5.621 | *** | Accepted |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Purohit, A.; Chopra, G.; Dangwal, P.G. Measuring the Effectiveness of the Project Management Information System (PMIS) on the Financial Wellness of Rural Households in the Hill Districts of Uttarakhand, India: An IS-FW Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113862

Purohit A, Chopra G, Dangwal PG. Measuring the Effectiveness of the Project Management Information System (PMIS) on the Financial Wellness of Rural Households in the Hill Districts of Uttarakhand, India: An IS-FW Model. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):13862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113862

Chicago/Turabian StylePurohit, Ajay, Gaurav Chopra, and Parshuram G. Dangwal. 2022. "Measuring the Effectiveness of the Project Management Information System (PMIS) on the Financial Wellness of Rural Households in the Hill Districts of Uttarakhand, India: An IS-FW Model" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 13862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113862

APA StylePurohit, A., Chopra, G., & Dangwal, P. G. (2022). Measuring the Effectiveness of the Project Management Information System (PMIS) on the Financial Wellness of Rural Households in the Hill Districts of Uttarakhand, India: An IS-FW Model. Sustainability, 14(21), 13862. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113862