Effects of Social Capital on Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Chinese Residents

Abstract

1. Introduction

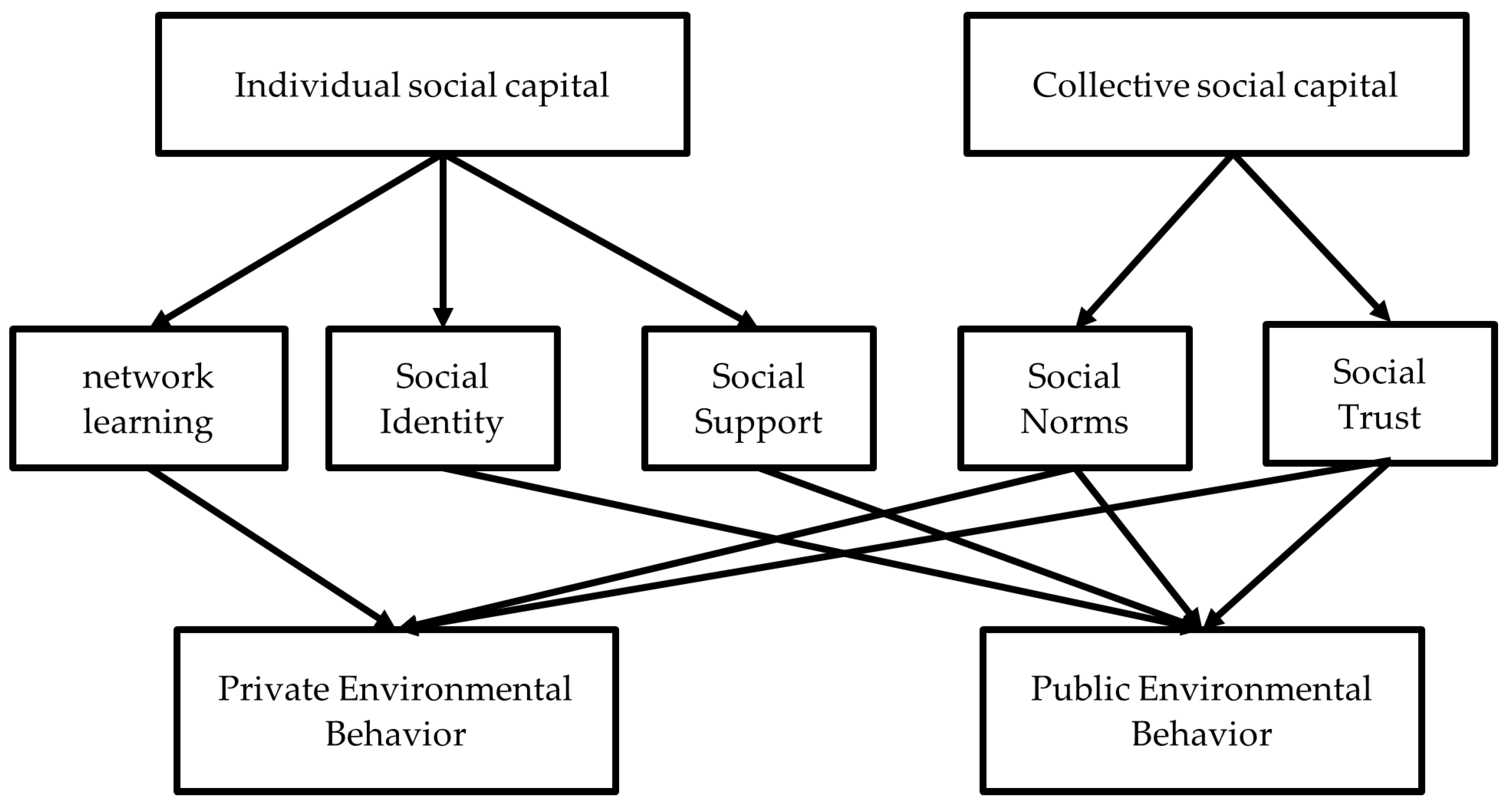

2. Literature Review and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Social Capital

2.2. Environmental Behavior

2.3. Social Capital and Environmental Behavior

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variable

3.2.3. Control Variable

3.2.4. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Effects of Social Capital on Private Pro-Environmental Behavior

4.2. Effects of Social Capital on Public Pro-Environmental Behavior

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- According to the 2020 Bulletin on China’s Ecological Environment, the National Ecological Environment Quality Will Continue to Improve in 2020. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1700822597313380478&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 16 June 2022). (In Chinese).

- Huang, K. Theoretical and practical research on public participation in environmental protection. People’s Forum 2015, 27, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, E.; Gick, M.L. Can health psychology help the planet? Applying theory and models of health behaviors to environmental actions. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Neaman, A.; Richards, B.; Mario, A. Explaining the Ambiguous Relations Between Income, Environmental Knowledge, and Environmentally Significant Behavior. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruderer Enzler, H.; Diekmann, A. All talk and no action? An analysis of environmental concern, income and greenhouse gas emissions in Switzerland. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 51, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Siefer, P.; Neaman, A.; Salgado, E.; Celis-Diez, J.; Otto, S. Human-Environment System Knowledge: A Correlate of Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15510–15526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Li, W.; Ling, S.; Dou, X.; Liu, X.Z. An Empirical Study on the Influence Path of Environmental Risk Perception on Behavioral Responses in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cin, C.K. Blaming the Government for Environmental Problems: A Multilevel and Cross-National Analysis of the Relationship between Trust in Government and Local and Global Environmental Concerns. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 971–992. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Soopramanien, D. Types of place attachment and pro-environmental behaviors of urban residents in Beijing. Cities 2019, 84, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A. The Wealth of Nations and Environmental Concern. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Public Support for Environmental Protection: Objective Problems and Subjective Values in 43 Societies PS: Political Science & Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; Volume 28, pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Gelissen, J. Explaining Popular Support for Environmental Protection: A Multilevel Analysis of 50 Nations. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 392–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R. Are the Affluent Prepared to Pay for the Planet? Explaining Willingness to Pay for Public and Quasi-Private Environmental Goods in Switzerland. Popul. Environ. 2010, 32, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brechin, S.R.; Kempton, W. Global Environmentalism: A Challenge to the Postmaterialism Thesis? Soc. Sci. Q. 1994, 75, 245–269. [Google Scholar]

- Brechin, S.R. Objective Problems, Subjective Values and Global Environmentalism: Evaluating the Postmaterialist Argument and Challenging a New Explanation. Soc. Sci. Q. 1999, 80, 793–809. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Mertig, A.G. Global Concern for the Environment: Is Affluence a Prerequisite? J. Soc. Issues 1995, 51, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; York, R. The Globalization of Environmental Concern and the Limits of the Postmaterialist Values Explanation: Evidence from Four Multinational Surveys. Sociol. Q. 2008, 49, 529–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampel, F.C.; Hunter, L.M. Cohort Change, Diffusion, and Support for Environmental Spending in the United States. Am. J. Sociol. 2012, 118, 420–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.F.; McAdam, D.; Scott, W.R.; Zald, M.N. Social Movements and Organization Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Y. Network Social Capital and Civic Engagement in Environmentalism in China. The dynamics of social capital and civic engagement in Asia; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Y. The Prevalence and the Increasing Significance of Guanxi. China Q. 2018, 235, 597–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Cheng, Y. Can social networks enhance residents’ environmental behavior? —An empirical study based on CGSS 2013 data. J. Hefei Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 35, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N. Conceptualizing Social Support. In Social Support, Life Events, and Depression; Lin, N., Dean, A., Ensel, W., Eds.; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W. Social capital: Theoretical debates and empirical studies. Sociol. Res. 2003, 18, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Tuning in, tuning out: The strange disappearance of social capital in America. Political Sci. Politics 1995, 28, 664–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Analysis and synthesis of research on responsible environmental behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1987, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.M.; Hatch, A.; Johnson, A. Cross-national Gender Variation in Environmental Behavior. Soc. Sci. Q. 2004, 85, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, S.; Katz-Gerro, T. Predicting Pro-environmental Behavior Cross-Nationally: Values, the Theory of Planned Behavior, and Value-Belief-Norm Theory. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 462–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital; The city reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 188–196. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.J.; Han, D.L. Economic development, environmental pollution and public environmental behavior--a multi-layer analysis based on CGSS2013 data. J. Renmin Univ. China 2016, 30, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, W.J.; Lei, J. Gender differences in environmental concern and environmentally friendly behavior among urban residents in China. J. Hainan Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2007, 25, 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.Y.; Lu, C.T. A multi-layer analysis of public environmental concern—an applied sociological study based on data from CGSS2003 in China. Sociol. Res. 2011, 26, 154–170+244–245. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H.E. Urban-rural differences in environmental behavior of Chinese residents and their influencing factors—Analysis based on CGSS data in 2013. Hebei J. 2021, 41, 198–204. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Hu, J. A study on the influence factors of public environmental participation in China--an empirical analysis based on provincial panel data in China. China Popul. -Resour. Environ. 2015, 25, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Xing, Y. Social capital and residents’ plastic recycling behaviors in China. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C. Waste sorting in context: Untangling the effectss of social capital and environmental norms. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.J. An analysis of gender differences in environmental friendly behavior among Chinese urban residents. J. China Univ. Geosci. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2008, 54, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.; Hong, D. Gender differences in environmental behavior in China. Popul. Environ. 2010, 32, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environmental activities or behavior | Never | Occasionally | Frequently |

| 1. Sorting garbage | 55.8 | 31.9 | 12.3 |

| 2. Discussing environmental issues with your relatives and friends | 51.1 | 41.0 | 7.9 |

| 3. Bringing your own shopping bags when purchasing daily necessities | 24.1 | 35.6 | 40.3 |

| 4. Reusing plastic bag for packaging | 18.7 | 31.1 | 50.2 |

| 5. Paying attention to environmental issues reported by media | 83.2 | 15.0 | 1.8 |

| 6. Donating for environmental protection | 50.0 | 36.9 | 13.1 |

| 7. Actively participating in environmental awareness-raising activities | 77.8 | 18.3 | 3.9 |

| 8. Actively engaging in environmental activities organized by environmental groups | 84.0 | 13.7 | 2.4 |

| 9. Maintenance of woods or green areas at your own expense | 85.5 | 10.8 | 3.8 |

| 10. Active participation in environmental complaints | 91.2 | 7.4 | 1.4 |

| Variables | Observations | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| Dependent variable: environmental behavior | |||||

| Private environmental behavior | 10039 | 4.24 | 2.36 | 0 | 10 |

| Public environmental behavior | 10039 | 0.91 | 1.58 | 0 | 10 |

| ISC | 10039 | 6.42 | 3.24 | 0 | 12 |

| CSC | 10039 | 6.34 | 1.30 | 2 | 10 |

| Age | 10039 | 56.95 | 16.11 | 25 | 105 |

| Male (comparison: female) * | 10039 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Education level | 10039 | 3.03 | 1.25 | 1 | 5 |

| Annual income | 10039 | 9.62 | 1.18 | 4.38 | 13.81 |

| N = 8910 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| ISC | 0.037 *** (0.007) | 0.036 *** (0.007) | |

| CSC | 0.039 * (0.017) | ||

| Province | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Age | 0.011 *** (0.002) | 0.012 *** (0.002) | 0.012 *** (0.002) |

| Annual income | 0.233 *** (0.025) | 0.231 *** (0.025) | 0.231 *** (0.025) |

| Male (comparison: female) | −0.505 *** (0.046) | −0.498 *** (0.046) | −0.50 *** (0.046) |

| Education level | 0.538 *** (0.024) | 0.542 *** (0.024) | 0.539 *** (0.024) |

| Cons | 0.962 ** (0.307) | 0.776 * (0.309) | 0.558 (0.322) |

| 0.234 | 0.236 | 0.236 |

| N = 8910 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| ISC | 0.041 *** (0.005) | 0.040 *** (0.005) | |

| CSC | 0.042 *** (0.012) | ||

| Control variables | |||

| Province | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Age | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.002 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) |

| Annual income | 0.072 *** (0.017) | 0.070 *** (0.017) | 0.070 *** (0.017) |

| Male (comparison: female) | 0.023 (0.032) | −0.015 (0.032) | −0.020 (0.032) |

| Education level | 0.282 *** (0.016) | 0.286 *** (0.016) | 0.284 *** (0.016) |

| Cons | −0.678 ** (0.214) | −0.885 *** (0.214) | −1.119 *** (0.224) |

| 0.183 | 0.189 | 0.190 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shi, J.; Lu, C.; Wei, Z. Effects of Social Capital on Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Chinese Residents. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113855

Shi J, Lu C, Wei Z. Effects of Social Capital on Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Chinese Residents. Sustainability. 2022; 14(21):13855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113855

Chicago/Turabian StyleShi, Jing, Chuntian Lu, and Zihao Wei. 2022. "Effects of Social Capital on Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Chinese Residents" Sustainability 14, no. 21: 13855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113855

APA StyleShi, J., Lu, C., & Wei, Z. (2022). Effects of Social Capital on Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Chinese Residents. Sustainability, 14(21), 13855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113855