How Do Remuneration Committees Affect Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure? Empirical Evidence from an International Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

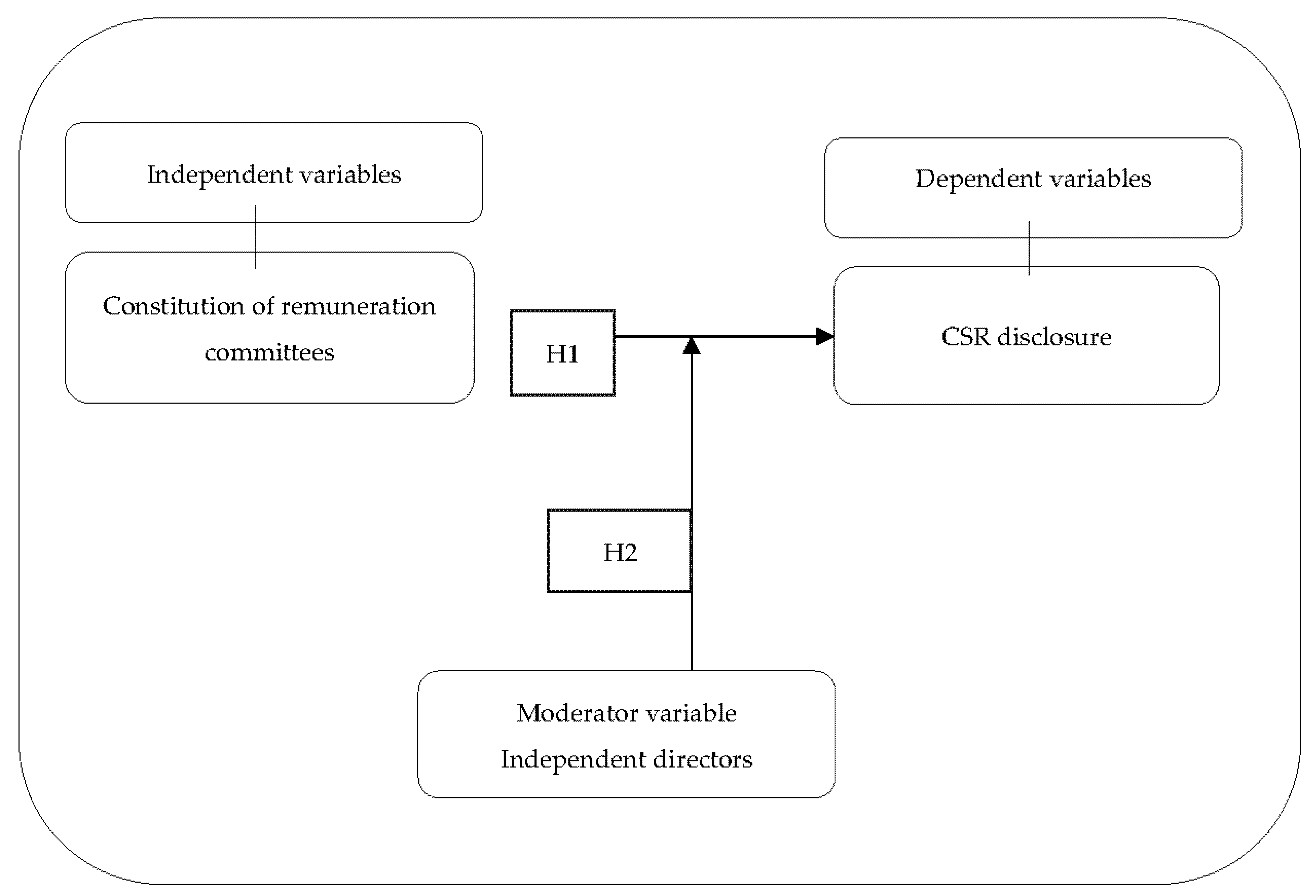

2.1. Remuneration Committees and CSR Disclosure

2.2. The Moderating Role of Independent Directors

3. Research Method

3.1. Sample

3.2. Variables

3.3. Regression Model Specification

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Regressions Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jamali, D.; Safieddine, A.; Rabbath, M. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility synergies and interrelationships. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2008, 16, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Simmons, J. Embedding corporate social responsibility in corporate governance: A stakeholder systems approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 119, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, M.; Laksmana, I. The impact of corporate social responsibility on risk taking and firm value. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ferrero, J.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; García-Sánchez, I.M.; Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and information asymmetry: The role of family ownership. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2018, 12, 885–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Villegas, J.; Pérez-Calero, L.; Hurtado-González, J.M.; Giráldez-Puig, P. Board attributes and corporate social responsibility disclosure: A meta-analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, J.; Nozawa, W.; Yagi, M.; Fujii, H.; Managi, S. Do environmental, social, and governance activities improve corporate financial performance? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallego-Álvarez, I.; Pucheta-Martínez, M.C. Corporate social responsibility reporting and corporate governance mechanisms: An international outlook from emerging countries. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2020, 3, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Muttakin, M.B.; Siddiqui, J. Corporate governance, and corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.R. The Strategic Use of Corporate Board Committees. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1987, 30, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, H.; Beldona, S.; Joshi, M. Institutional investor heterogeneity: Implications for strategic decisions. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 1998, 6, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, N.B.; Hutchinson, M. Corporate governance and risk management: The role of risk management and compensation committees. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2013, 9, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Credible commitments: Using hostages to support exchange. Am. Econ. Rev. 1983, 73, 519–540. [Google Scholar]

- Unified Good Governance Code of Listed Companies; Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores: Madrid, Spain, 2006. Available online: https://www.cnmv.es/DocPortal/Publicaciones/CodigoGov/Codigo_unificado_Ing_04en.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Good Governance Code of Listed Companies; Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores: Madrid, Spain, 2020. Available online: https://www.cnmv.es/DocPortal/Publicaciones/CodigoGov/CBG_2020_ENen.PDF (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Conyon, M.; Peck, S. Board control, remuneration committees, and top management compensation. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of ownership and control. J. Law Econ. 1983, 26, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmania, M.; Septiani, A. Pengaruh karakteristik tata kelola dan karakteristik perusahaan terhadap keputusan perusahaan terkait sustainability reporting. Diponegoro J. Account. 2019, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zaid, M.A.; Abuhijleh, S.T.; Pucheta-Martínez, M.C. Ownership structure, stakeholder engagement, and corporate social responsibility policies: The moderating effect of board independence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1344–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Tilt, C. Board composition and corporate social responsibility: The role of diversity, gender, strategy and decision making. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 138, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samet, M.; Jarboui, A. CSR, agency costs and investment-cash flow sensitivity: A mediated moderation analysis. Manag. Financ. 2017, 43, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harymawan, I.; Agustia, D.; Nasih, M.; Inayati, A.; Nowland, J. Remuneration committees, executive remuneration, and firm performance in Indonesia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.A.; D’Souza, F.; Simkins, B.J.; Simpson, W.G. The gender and ethnic diversity of US boards and board committees and firm financial performance. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2010, 18, 396–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, A.L.; Mulherin, J.H. How do Corporate Boards Balance Monitoring and Advising? The Situational Use of Special Committees in Corporate Takeovers. The Situational Use of Special Committees in Corporate Takeovers (27 November 2012). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1783064 (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Ruigrok, W.; Peck, S.; Tacheva, S.; Greve, P.; Hu, Y. The determinants and effects of board nomination committees. J. Manag. Gov. 2006, 10, 119–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kanapathippillai, S.; Mihret, D.; Johl, S. Remuneration committees and attribution disclosures on remuneration decisions: Australian evidence. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 1063–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttipun, M. The influence of board composition on environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure of Thai listed companies. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2021, 18, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeysekera, I. Role of remuneration committee in narrative human capital disclosure. Account. Financ. 2012, 52, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alotaibi, K. Determinants and Consequences of CSR Disclosure Quantity and Quality: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Business, Plymouth University, Plymouth, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.J. Corporate performance and managerial remuneration: An empirical analysis. J. Account. Econ. 1985, 7, 11–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadbury, A. Report of the Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance; Gee Publishing: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Laux, C.; Laux, V. Board committees, CEO compensation, and earnings management. Account. Rev. 2009, 84, 869–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Appiah, K.O.; Chizema, A. Remuneration committee and corporate failure. Corp. Gov. 2015, 15, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusnadi, Y.; Leong, K.S.; Suwardy, T.; Wang, J. Audit committees and financial reporting quality in Singapore. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 139, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanapathippillai, S.; Johl, S.K.; Wines, G. Remuneration committee effectiveness and narrative remuneration disclosure. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2016, 40, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gago, R.; Cabeza-García, L.; Nieto, M. Independent directors’ background and CSR disclosure. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, F.; Ntim, C.G. Executive compensation, sustainable compensation policy, carbon performance and market value. Br. J. Manag. 2020, 31, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, N. Do corporate governance mechanisms influence CEO compensation? An empirical investigation of UK companies. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2007, 17, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibiletti, V.; Marchini, P.L.; Furlotti, K.; Medioli, A. Does corporate governance matter in corporate social responsibility disclosure? Evidence from Italy in the “era of sustainability”. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 28, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Pearce, J.A. Boards of directors and corporate financial performance: A review and integrative model. J. Manag. 1989, 15, 291–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, C.M.; Dalton, D.R. Corporate governance and the bankrupt firm: An empirical assessment. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisbach, M.S. Outside directors and CEO turnover. J. Financ. Econ. 1988, 20, 431–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, R.; Bahadar, S.; Kayani, U.N.; Arslan, M. Role of media and independent directors in corporate transparency and disclosure: Evidence from an emerging economy. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 18, 858–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saona, P.; Muro, L.; Alvarado, M. How do the ownership structure and board of directors’ features impact earnings management? The Spanish case. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2020, 31, 98–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuzi, S.F.S.; Halim, S.A.A.; Julizaerma, M.K. Board independence and firm performance. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giraldez, P.; Hurtado, J.M. Do independent directors protect shareholder value? Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2014, 23, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoto, M.A.; Jo, H. Corporate governance and CSR nexus. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.A.; Howard, D.P.; Angelidis, J.P. Board members in the service industry: An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility orientation and directional type. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 47, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, B.W.; de Sousa-Filho, J.M. Board structure and environmental, social, and governance disclosure in Latin America. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jizi, M. The influence of board composition on sustainable development disclosure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbash, M. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 740–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chhaochharia, V.; Grinstein, Y. CEO compensation and board structure. J. Financ. 2009, 61, 231–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Lavers, S. Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, K.H.; Li, D. The impact of CSR on relationship quality and relationship outcomes: A perspective of service employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person- centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M.C.; Gallego-Álvarez, I. The Role of CEO Power on CSR Reporting: The Moderating Effect of Linking CEO Compensation to Shareholder Return. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucheta-Martínez, M.C.; Gallego-Álvarez, I. An international approach of the relationship between board attributes and the disclosure of corporate social responsibility issues. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barako, D.; Brown, A. Corporate social reporting and board representation: Evidence from the Kenyan banking sector. J. Manag. Gov. 2008, 12, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Luo, L.; Tang, Q. Gender diversity, board independence, environmental committee and greenhouse gas disclosure. Br. Account. Rev. 2015, 47, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, R.; Cooke, T. The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. J. Account. Public Policy 2005, 24, 391–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jizi, M.; Salama, A.; Dixon, R.; Stratling, R. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from the US banking sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chau, G.; Gray, S. Family ownership, board independence and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Hong Kong. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2010, 19, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, R.; Mulcahy, M. Board structure, ownership, and voluntary disclosure in Ireland. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2008, 16, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverte, C. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure ratings by Spanish listed firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 88, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in developed and developing countries: A literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintoki, M.B.; Linck, J.S.; Netter, J.M. Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 105, 581–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambeault, D.; DeZoort, F.T. Auditor opinion shopping and the audit committee: An analysis of suspicious auditor switches. Int. J. Audit. 2001, 5, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, S.; Schipani, C.A.; Seyhun, H. The elusive monitoring function of independent directors. University of Pennsylvania. J. Bus. Law 2018, 21, 235–287. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, M.A. Environmental, social and governance disclosures in Europe. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2015, 6, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Theoretical insights on integrated reporting: The inclusion of non-financial capitals in corporate disclosures. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2018, 23, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Description |

|---|---|

| CSR_INDEX | The ratio between the aggregation of 140 items focused on environmental, social and economic issues and the total number of items analyzed, which codes as 1 if the firm disclose the CSR information related each item, and 0 |

| RC_P | This variable takes a value of 1 if a remuneration committee existence in the firm or 0 otherwise |

| PBIND | Ratio between total number of independent directors on boards on total number of directors on boards |

| FEM_BOARD | Dichotomous variable that codes as 1 if the board of directors have female directors, and 0 otherwise |

| CEO_DUALITY | Dichotomous indicator that codes as 1 when the CEO of the company is the chairperson of the board, and 0 otherwise |

| LTA | The log of total assets |

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSR_INDEX | 343.356 | 1.99 | 7.765 |

| RC_P | 343.356 | 0.07 | 0.252 |

| PBIND | 343.356 | 0.05 | 0.217 |

| FEM_BOARD | 343.356 | 0.05 | 0.221 |

| CEO_DUALITY | 343.356 | 0.02 | 0.150 |

| LTA | 343.356 | 10.36 | 9.840 |

| CSR_INDEX | RC_P | PBIND | FEM_BOARD | CEO_DUALITY | LTA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR_INDEX | 1.000 | |||||

| RC_P | 0.484 | 1.000 | ||||

| PBIND | 0.524 | 0.573 | 1.000 | |||

| FEM_BOARD | 0.548 | 0.638 | 0.677 | 1.000 | ||

| CEO_DUALITY | 0.329 | 0.416 | 0.433 | 0.458 | 1.000 | |

| LTA | 0.119 | 0.068 | 0.106 | 0.101 | 0.548 | 1.000 |

| MODEL 1 Coef. P > |t| | MODEL 2 Coef. P > |t| | |

|---|---|---|

| CSR_INDEX(t−1) | 0.28 | 0.24 |

| RC_P | 5.10 | 6.67 |

| RC_P × PBIND | −5.85 | |

| PBIND | 8.16 | 11.49 |

| FEM_BOARD | 9.35 | 8.99 |

| CEO_DUALITY | 1.84 | 1.75 |

| LTA | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Year effects | Yes | Yes |

| Wald χ2 test | 5144.05 | 4884.80 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bel-Oms, I.; Segarra-Moliner, J.R. How Do Remuneration Committees Affect Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure? Empirical Evidence from an International Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020860

Bel-Oms I, Segarra-Moliner JR. How Do Remuneration Committees Affect Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure? Empirical Evidence from an International Perspective. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020860

Chicago/Turabian StyleBel-Oms, Inmaculada, and José Ramón Segarra-Moliner. 2022. "How Do Remuneration Committees Affect Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure? Empirical Evidence from an International Perspective" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020860

APA StyleBel-Oms, I., & Segarra-Moliner, J. R. (2022). How Do Remuneration Committees Affect Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure? Empirical Evidence from an International Perspective. Sustainability, 14(2), 860. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020860