Human Rights and Socio-Environmental Conflicts of Mining in Mexico: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Motivation and Scope

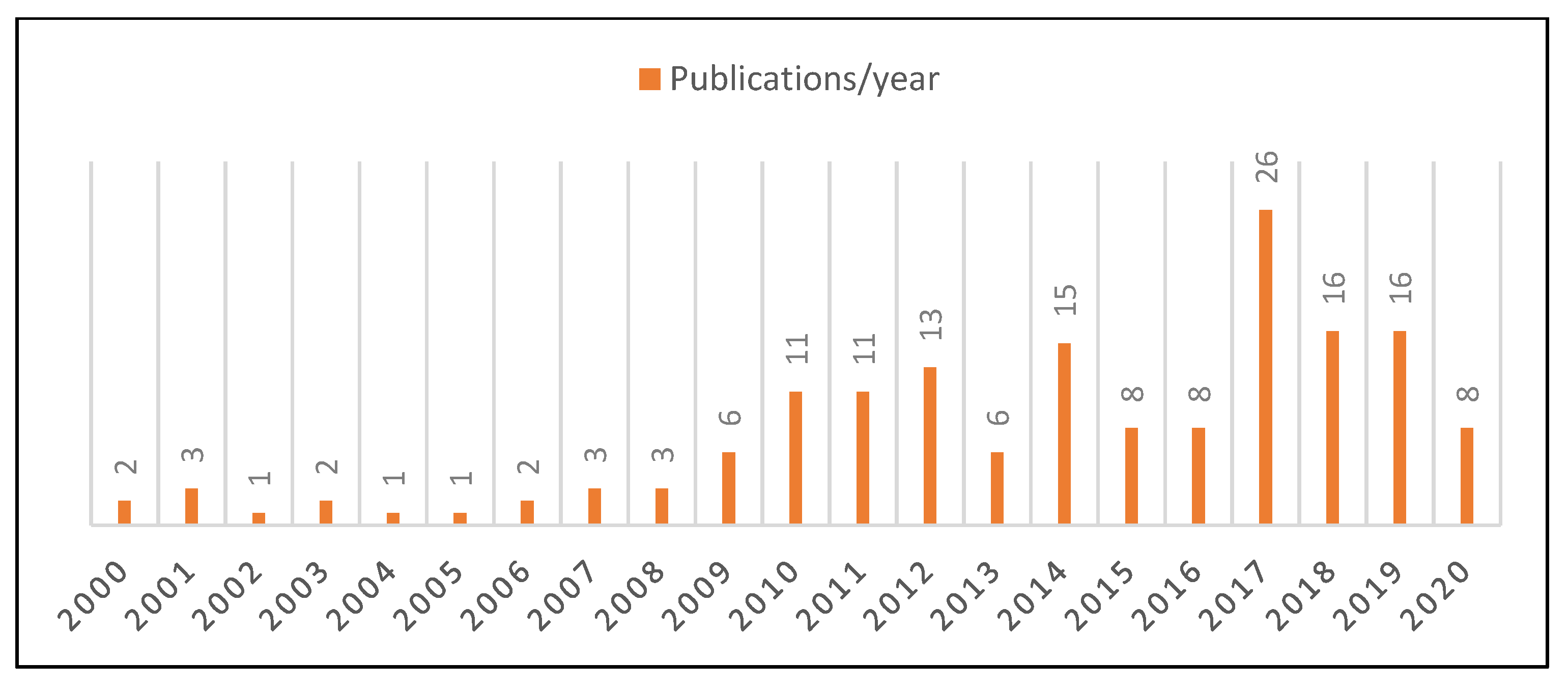

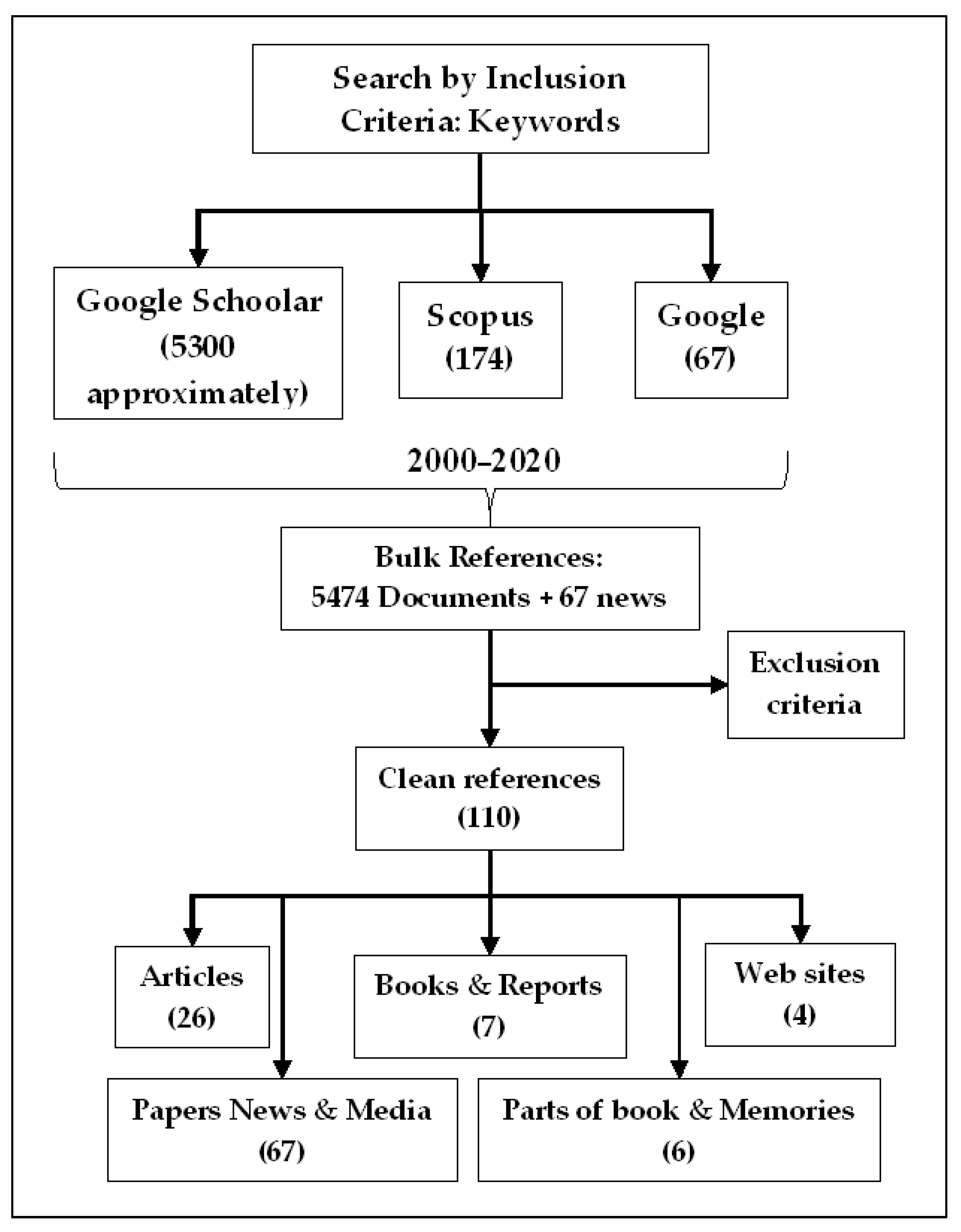

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Socio-Environmental Conflicts

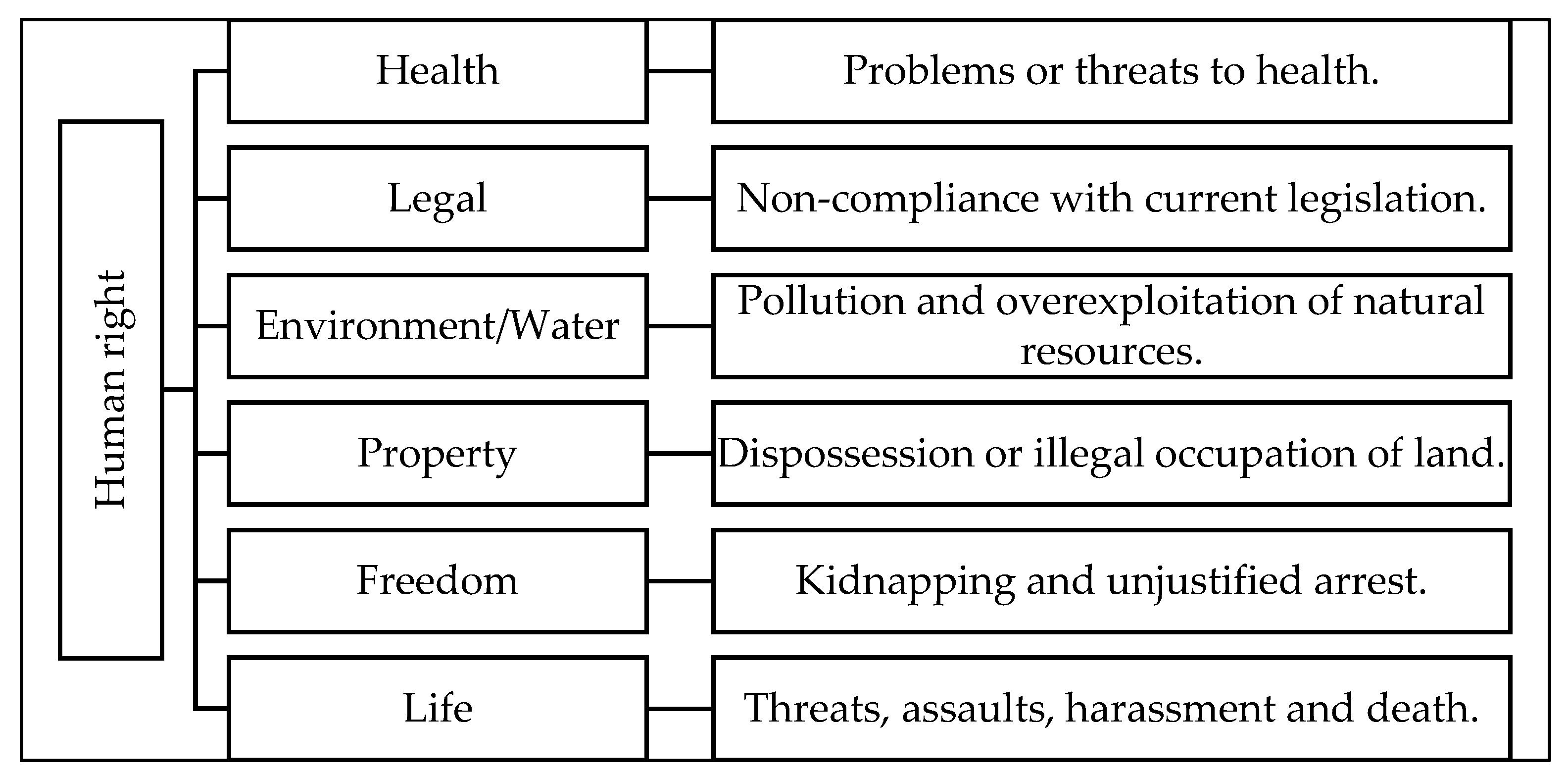

4.2. Violations to Human Rights of the Mining Sector in Latin America

4.3. Violations to Human Rights in the Mining Sector in Mexico

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Third Generation Rights | |

|---|---|

| To peace | Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), Article 3: “Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person.” Not recorded in Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. |

| To economic development | Declaration on the right to development (1986), Article 1: “The right to development is an inalienable human right under which every human person and all peoples are entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development, in which all human rights and fundamental freedoms can be fully realized.” Not recorded in Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. |

| To self-determination | Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples (1960), Declarations 2 and 4: “2. All peoples have the right to self-determination; under that right, they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social, and cultural development.”; “4. All armed action or repressive measures of all kinds directed against dependent peoples shall cease to enable them to exercise peacefully and freely their right to complete independence, and the integrity of their national territory shall be respected.” Not recorded in Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. |

| To a healthy environment | Political Constitution of the United Mexican States, Article 4: “Any person has the right to a healthy environment for their development and well-being. The State will guarantee respect to such rights. But, on the other hand, environmental damage and deterioration will generate liability for whoever provokes them in terms of the provisions by the law.” |

| To benefit from the common heritage of humanity | United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982): “Desiring by this Convention to develop the principles embodied in resolution 2749 (XXV) of 17 December 1970, in which the General Assembly of the United Nations solemnly declared among other things that the area of the seabed and ocean floor and the subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, as well as its resources, are the common heritage of mankind, the exploration, and exploitation of which shall be carried out for the benefit of mankind as a whole, irrespective of the geographical location of States,”. They are not recorded in the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. |

| To solidarity | It is not a clear right. Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), Article 22: “Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and under the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality.” Not recorded in Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. |

| Right | Textual Quote | Reference in the Constitution | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health | “Every person has the right to health protection. The law shall determine the bases and terms to access health services. It shall establish the competence of the Federation and the Local Governments concerning sanitation according to the item XVI in Article 73 of this Constitution.” | Article 4 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The last reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. The added paragraph in the Official Journal of the Federation on 2 February 1983. | |

| Legal | According to the principle of legality, the authorities must adhere to the Constitution, laws, and international treaties established and not to the will of the people: “No one may be disturbed in his person, family, home, papers or possessions, except by written order of a competent authority, duly grounded in law and fact which sets forth the legal cause of the proceeding.” | Article 16 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The last reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. The added paragraph in the Official Journal of the Federation on 15 September 2017. | |

| “Restriction or suspension of constitutional rights and guarantees should be based and justified on the provisions established by this Constitution, should be proportional to the danger, and should observe the principles of legality, rationality, notification, publicity, and non-discrimination.” | Article 29 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The latest reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. | ||

| Environment | Water | “Any person has the right of access, provision, and drainage of water for personal and domestic consumption in a good, healthy, acceptable, and affordable manner. The State will guarantee such right and the law will define the bases, subsidies, and modality for the equitable and sustainable access and use of the freshwater resources, establishing the participation of the Federation, local governments, and municipalities, as well as the participation of the citizens for the achievement of such purposes.” | Article 4 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The latest reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. The added paragraph in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 February 2012. |

| Healthyenvironment | “Any person has the right to a healthy environment for their development and well-being. The State will guarantee respect to such rights. Conversely, environmental damage and deterioration will generate liability for whoever provokes them in terms of the provisions by the law.” | Article 4 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The latest reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. The added paragraph in the Official Journal of the Federation on 6 June 1999. | |

| Property | “The property of all land and water within national territory is originally owned by the Nation, who has the right to transfer this ownership to particulars. Hence, private property is a privilege created by the Nation.” “Expropriation is authorized only where appropriate in the public interest and subject to payment of compensation.” “The Nation shall always have the right to impose on private property such restrictions as the public interest may demand, as well as to regulate, for social benefit, the use of natural resources which are susceptible of appropriation, to make an equitable distribution of public wealth, to conserve them, to achieve a balanced development of the country and to improve the living conditions of the rural and urban population. Consequently, appropriate measures shall be issued to order human settlements and define adequate provisions, reserves, land, water, and forest use. Furthermore, such measures shall seek construction of infrastructure; planning and regulation of the new settlements and their maintenance, improvement, and growth; preservation and restoration of ecological balance; division of large rural estates; collective exploitation and organization of the farming cooperatives; development of the small rural property; stimulation of agriculture, livestock farming, forestry, and other economic activities in rural communities; and to avoid destruction of natural resources and damages against property to the detriment of society.” | Article 27 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The latest reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. Reformed paragraph in Official Journal of the Federation 6 February 1976; 10 August 1987; and 6 January 1992. | |

| Freedom | “No one can be deprived of his freedom, properties or rights without a trial before previously established courts, complying with the essential formalities of the proceedings and according to those laws issued beforehand.” | Article 14 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The latest reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. Reformed paragraph in Official Journal of the Federation on 9 December 2005. | |

| “No arrest summons may be issued except for the judicial authority upon previous accusation or commission complaint because of an act which is described as a crime by the law, punishable with imprisonment. Unless there is evidence to prove a committed crime with enough elements to believe that the suspect committed it or was an accessory.” | Article 16 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The latest reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. Reformed paragraph in Official Journal of the Federation on 6 June 2009. Errata in Official Journal of the Federation on 25 June 2009. | ||

| “No arrest before a judicial authority may exceed seventy-two hours from the time the defendant is brought under custody, without a formal order of entailment. The process must set forth the crime he is charged with, the place, time, and circumstances of the crime, as well as the evidence furnished by the preliminary criminal inquiry, which must be sufficient to establish that a crime has been committed and the potential liability of the suspect.” | Article 19 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The latest reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. | ||

| Life | “Death penalty, mutilation, and infamous penalties, as well as branding, flogging, beating with sticks, and torture of any kind, the imposition of excessive fines, confiscation of property and any other cruel, unusual and transcending punishments are prohibited. Furthermore, every penalty shall be in proportion to the crime committed and the legally-protected interest.” | Article 22 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The latest reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. | |

| “In the issued decrees, the exercise to non-discrimination rights, for the recognition of legal personality, life, personal integrity, family protection, name, which may not be restricted or suspended, nationality; child rights, political rights; freedoms of thinking, conscience and religious belief. The principle of legality and retroactivity; death penalty prohibition, slavery, and servitude; enforced disappearance and torture; and the judicial guarantees essential for the protection of such rights.” “Restriction or suspension of constitutional rights and guarantees should be based and justified on the provisions established by this Constitution, should be proportional to the danger, and should observe the principles of legality, rationality, notification, publicity, and non-discrimination.” | Article 29 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States. The latest reform was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 8 May 2020. | ||

References

- Franks, D.M.; Davis, R.; Bebbington, A.J.; Ali, S.H.; Kemp, D.; Scurrah, H. Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business cost. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7576–7581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mancini, L.; Sala, S. Social impact assessment in the mining sector. Review and comparison of indicators frameworks. Resour. Policy 2018, 57, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haalboom, B. The intersection of corporate social responsibility guidelines and indigenous rights: Examining neoliberal governance of a proposed mining project in Suriname. Geoforum 2012, 43, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idemudia, U.; Kwakyewah, C.; Muthuri, J. Mining, the environment, and human rights in Ghana: An area of limited statehood perspective. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 2919–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westorn, H.B.; Bollier, D. Toward a recalibrated human right to a clean and healthy environment: Making the conceptual transition. J. Hum. Rights Environ. 2013, 4, 116–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzé, L.J. Human rights and the environment in the Anthropocene. Anthr. Rev. 2014, 1, 252–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendezcarlo, V.; Lizardi-Jiménez, M.A. Environmental Problems and the State of Compliance with the Right to a Healthy Environment in Mining Region of Mexico. Int. J. Chem. Reac. Eng. 2020, 18, 20190179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsah-Brown, D. Environment, human rights and mining conflicts in Ghana. In Human Rights & the Environment. Conflicts and Norms in a Globalizing World; Zarsky, L., Ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, London, UK, 2001; pp. 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar Leib, L. Human Rights and the Environment: Philosophical, Theoretical and Legal Perspectives; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Devia, C.; Leguizamón, J. Procesos de paz y conflicto en África: Angola, República Democrática del Congo y Sierra Leona (Peace and Conflict Processes in Africa: Angola, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sierra Leone). Rev. Análisis Int. 2014, 5, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, J.E.; Gobernador, C. El territorio como elemento fundamental de la resistencia al desplazamiento forzado de los pueblos indígenas de Colombia (The territory as a fundamental element of the resistance to forced displacement of the indigenous peoples of Colombia). In Destierros y Desarraigos, Proceedings of the Memorias del II Seminario Internacional. Desplazamiento: Implicaciones y Retos Para la Gobernabilidad, la Democracia y los Derechos Humanos, Bogota, Colombia, 4–6 September 2003; CODHES, OIM-Misión Colombia: Colombia, 2003; pp. 71–80. Available online: https://repository.iom.int/handle/20.500.11788/875?locale-attribute=en (accessed on 6 January 2022).

- Knox, J.H. Defensores de Derechos Humanos Ambientales. Una Crisis Global (Defenders of Environmental Human Rights. A Global Crisis); Universal Rights Group: Versoix, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tetreault, D.; McCulligh, C.; Lucio, C. An Introduction to Social Environmental Conflicts and Alternatives in Mexico. In Social Environmental Conflicts in Mexico. Resistance to Dispossession and Alternatives from Below; Tetrault, D., McCulligh, C., Lucio, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe, S.; Rodríguez, G. México (Mexico). In Conflictos Mineros en América Latina: Extracción, saqueo y agresión. Estado de la situación en 2018 (Mining Conflicts in Latin America: Extraction, Looting and Aggression. State of the Situation in 2018); OCMAL: Chalchiuites, Mexico, 2019; pp. 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Svampa, M. Las Fronteras del Neoextractivismo en América Latina: Conflictos socioambientales, Giro Ecoterritorial y Nuevas Dependencias (The Borders of Neo-Extractivism in Latin America: Socio-Environmental Conflicts, Ecoterritorial Shift and New Dependencies), 1st ed.; CALAS Maria Sibylla Merian Center: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sbert, C. Amparos Filed by Indigenous Communities against Mining Concessions in Mexico: Implications for a Shift in Ecological Law. Mex. Law Rev. 2018, 10, 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Raftopoulos, M. Contemporary debates on social-environmental conflicts, extractivism and human rights in Latin America. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2017, 21, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, G.; Bonfill, X. Declaración PRISMA: Una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis (PRISMA statement: A Proposal to Improve the Publication of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyzes). Med. Clínica 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Span. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 3, e1000097. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, B.C.; Bayliss, H.R.; Haddaway, N.R. Beyond PRISMA: Systematic reviews to inform marine science and policy. Mar. Policy 2015, 62, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D. Evaluations of the uptake and impact of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement and extensions: A scoping review. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartos, O.J.; Wehr, P. Using Conflict Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, M. Conflictos ambientales, socioambientales, ecológico distributivos, de contenido ambiental… Reflexionando sobre enfoques y definiciones (Environmental, Socio-Environmental, Ecological Distributive, Environmental Content Conflicts … Reflecting on Approaches and Definitions). Boletín Ecos 2009, 6, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- López, R.; Somuano, M.; Ortega, R. David contra Goliat: ¿cómo los movimientos ambientales se enfrentan a las grandes corporaciones? (David vs. Goliath: How Do Environmental Movements Confront Big Corporations?). Am. Lat. Hoy 2018, 79, 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, S.; Mallet, A. Unhearthing power: A decolonial analysis of the Samarco mine disaster and Brazilian mining industry. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 704–715. [Google Scholar]

- Carranza, D.M. Socio-environmental conflicts: An underestimated threat to biodiversity conservation in Chile. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 110, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudynas, E. Conflictos y extractivismo: Conceptos, contenidos y dinámicas (Conflicts and extractivism: Concepts, contents and dynamics). Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2014, 27, 79–116. [Google Scholar]

- Garibay, C. Paisajes de acumulación minera por desposesión campesina en el México actual (Landscapes of mining accumulation by peasant dispossession in present-day Mexico). In Ecología política de la minería en América Latina. Aspectos socioeconómicos, legales y ambientales de la mega minería (Political Ecology of Mining in Latin America. Socioeconomic, Legal and Environmental Aspects of Mega Mining); UNAM, Centro de Investigaciones Interdisciplinarias en Ciencias y Humanidades: Federal District, Mexico, 2010; pp. 133–182. [Google Scholar]

- Seoane, J. Neoliberalismo y ofensa extractivista. Actualidad de la acumulación por despojo (Neoliberalism and extractivist offensive. Actuality of accumulation by dispossession). Theomai 2012, 26, (second semester). [Google Scholar]

- Porto, M.F.; Milanez, B. Eixos de desenvolvimiento económico e geração de conflitos socioambientais no Brasil: Desafios para a sustentabilidade e a justiça ambiental (Axes of Economic Development and Generation of Socio-Environmental Conflicts in Brazil: Challenges for Sustainability and Environmental Justice). Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2009, 14, 1983–1994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, N.; Gómez, C. La maldición de los recursos naturales (The Curse of Natural Resources). Ens. Rev. Econ. 2014, 33, 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, M.F. Deterioro y resistencias. Conflictos socioambientales en México (Deterioration and Resistance. Socio-Environmental Conflicts in Mexico). In Conflictos Socioambientales y Alternativas de la Sociedad Civil (Socio-Environmental Conflicts and Alternatives of Civil Society); ITESO: Guadalajara, Mexico, 2012; pp. 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tetreault, D. Social Environmental Minings Conflicts in Mexico. Lat. Am. Perspect. 2015, 42, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, E.E. Derechos de Tercera Generación (Third Generation Rights). Podium Notar. 2006, 34, 249–257. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, V.; Garrido, D.; Barrera-Basols, N. Conflictos socioambientales, resistencias ciudadanas y violencia neoliberal en México (Socio-Environmental Conflicts, Citizen Resistance and Neoliberal Violence in Mexico). Ecol. Política 2013, 46, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- González, S. La Jornada. México, uno de los Países de AL con más Problemas con Mineras: Cepal (Mexico, One of the Latin American Countries with the Most Problems with Mining Companies: Cepal). 2013. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2013/10/20/economia/024n1eco (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Observatorio de Conflictos Mineros de América Latina (OCMAL) (Observatory of Mining Conflicts in Latin America). Available online: https://www.ocmal.org/ (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Zaremberg, G.; Guarneros-Meza, V.; Flores-Ivich, G.; Torres Wong, M. Conversing with Goliath: Hemerographic Database on Conflicts in Mining, Hydrocarbon, Hydroelectric and Wind-Farm Industries in Mexico. 2019. Available online: http://observandoagoliat.com/ (accessed on 26 July 2020).

- Environmental Justice Atlas. Available online: www.ejatlas.org (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Grieta, Medio para Armar (Crack, Medium to Assemble). Available online: www.grieta.org (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Ramírez, N.L. Mapeo y Análisis Espacial de Conflictos Ambientales en México (Mapping and Spatial Analysis of Environmental Conflicts in Mexico); PNUD: Mexico-INECC, Mexico City, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Duque, L.; Pérez, M.; Betancour, A. Spoliation, socio-environmental conflicts and human rights violation Implications of large scale mining in Latin America. Rev. UDCA Actual. Divulg. Científica 2020, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.J. Tratado de Derecho Ambiental Mexicano. La Responsabilidad por el daño Ambiental (Mexican Environmental Law Treaty. Liability for Environmental Damage); UNAM: Azcapotzalco, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Government. Political Constitution of the United Mexican States; Last Reform Published DOF 28-05-2021; Official Journal of the Federation: Mexico City, Mexico.

| Stage | Characteristic | Manifestation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-conflict | Requisitions and claims privately. | Letters to companies or government offices. | |

| Defensive reaction | Low-intensity conflict | Use of formalized institutional frameworks to express themselves publicly. | Press. Creation of commissions. Use of social networks. Collective lawsuits. |

| Medium intensity conflict | Greater public exposure. Mobilization of citizen groups. Active protest practices. No physical violence. Support and tolerance by the state. Press coverage. | Marches and events in public areas. Adhesion of opposition groups. | |

| High-intensity conflict | More energetic actions. Physical violence may occur. | Mobilizations of large groups. Citizen resistance. Road and street cuts. Seizure and/or damage of facilities. | |

| Resolution | Absence of claims and social demonstrations. | Agreements and/or compensation between social actors and mining companies. | |

| Country | Mining Conflicts | Period |

|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 55 | 1980–2018 |

| Chile | 49 | 1985–2018 |

| Peru | 42 | 1992–2018 |

| Argentina | 28 | 1997–2016 |

| Brazil | 26 | 1979–2012 |

| Colombia | 19 | 1983–2012 |

| Bolivia | 10 | 1972–2010 |

| Guatemala | 10 | 1999–2011 |

| Ecuador | 9 | 1995–2017 |

| Nicaragua | 7 | 2005–2017 |

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Reforms aim for the free flow of goods and capital. Mining laws advantages. Reform of Article 27 of the Constitution allows converting common and communal lands into private property. Government agencies poorly regulate and sanction mining activities. | Corrupt politicians, police officers, and weak institutional ethics. Acute poverty in peasant regions. Lack of employment in environments with high competitive pressure. Weakness of social organizations to resist coercion and capture of their institutions. An ideology assumes that all kinds of corporate investments are suitable. |

| State | Municipality | Year | Cause of Conflict | Human Rights Violated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguascalientes | Asientos | 2015 | Pollution. | W |

| Asientos | 2016 | Fauna. | HE | |

| Baja California | Mexicali | 1990 | Illegal exploitation. | W |

| Mining waste. | HE | |||

| Illegal occupation. | P | |||

| Ensenada | 2010 | Overexploitation. | W | |

| Environmental damage. | HE | |||

| Baja California Sur | La Paz | 2019 | Public force. | LI |

| La Paz | 2010 | Attempted environmental damage. | HE | |

| Bahía de Ulloa | 2014 | Marine fauna. | HE | |

| Illegal environmental activity. | LE | |||

| Freedom of press and expression. | F | |||

| Santa Rosalia | 2016 | Marine fauna. | HE | |

| Campeche | Champoton | 2011 | Logging. | HE |

| Illegal environmental activity. | LE | |||

| Chiapas | Motozintla | 2007 | Threats of death. | LI |

| Arrests. | F | |||

| Escuintla | 2015 | Health problems. | H | |

| Environmental damage. | HE | |||

| Chihuahua | Madera | 2007 | Mining waste. | HE |

| Illegal occupation. | P | |||

| Murders. | LI | |||

| Kidnappings. | F | |||

| Samalayuca | 2015 | Environmental damage. | HE | |

| Pollution. | W | |||

| Guadalupe y Calvo | 2016 | Displacements. | P | |

| Murders. | LI | |||

| Coahuila | Ocampo | 1980 | Breach of agreements. | LE |

| Illegal occupation. | P | |||

| Arrests | F | |||

| Colima | Manzanillo | 2016 | Fauna. Mining waste. | HE |

| Damage to buildings. | P | |||

| Ejido Los Potros | 2016 | Health problems. | H | |

| Displacements. Illegal occupation. | P | |||

| Aggressions. | LI | |||

| Zacualpan | 2014 | Omission of public assembly. | LE | |

| Criminalization. | F | |||

| Threats. | LI | |||

| Durango | Gomez Palacio | 2017 | Illegal environmental activity. | HE |

| Repression. | F | |||

| Torture. | LI | |||

| Tlahualilo | 2011 | Illegal occupation. | P | |

| Repression. | F | |||

| Guanajuato | Mineral del Cedro | 2008 | Mining waste. | HE |

| Pollution. | W | |||

| Guerrero | Cocula | 2007 | Pollution. | W |

| Harassment. | LI | |||

| Mezcala | 2007 | Health problems. | H | |

| Illegal occupation. | P | |||

| Breach of agreements. | LE | |||

| Arrests. | LI | |||

| Hidalgo | Molango | 1964 | Environmental damage. | HE |

| Health problems. | H | |||

| Pachuca de Soto | 2016 | Mining waste. | HE | |

| Jalisco | Cuautitlan de Garcia Barragan | 2013 | Pollution. | W |

| Breach of procedures. | LE | |||

| Repression. | F | |||

| Mexico State | Temascaltepec | 2007 | Illegal environmental activity. Mining waste. | HE |

| Torture and murderer. | LI | |||

| Michoacan | San Miguel de Aquila | 2000 | Breach of agreements. | LE |

| Criminalization. | F | |||

| Morelos | Micatlan | 2012 | Risk of pollution. | W |

| Risk of environmental damage. | HE | |||

| Nayarit | Buenaventura | 2018 | Breach of procedures. | LE |

| Murderer. | LI | |||

| Oaxaca | Ocotlan de Morelos | 2002 | Environmental damage. | HE |

| Illegal occupation. | P | |||

| Repressions. | F | |||

| Murderer. | LI | |||

| Pollution. | W | |||

| Tlacolula de Matamoros | 2013 | Pollution. | W | |

| Arrests | F | |||

| Puebla | Tetela de Ocampo | 2012 | Environmental damage. | HE |

| Public participation. | F | |||

| Tlatlauquitepec | 2015 | Scarcity. | W | |

| Omission of information. | LE | |||

| Illegal occupation. | P | |||

| Tlatlauquitepec | 2015 | Mining concessions. | P | |

| San Luis Potosi | Cerro de San Pedro | 1995 | Breach of procedures. | LE |

| Illegal occupation. | P | |||

| Public force. | LI | |||

| Sonora | Cananea | 2014 | Pollution. | W |

| Health problems. | H | |||

| Breach of agreements. | LE | |||

| Arrests. | F | |||

| Sahuaripa | 2005 | Damage to buildings. | P | |

| Health problems. | H | |||

| Pollution. | W | |||

| Breach of agreements. | LE | |||

| Mining waste. | HE | |||

| Veracruz | Alto Lucero | 2011 | Illegal environmental activity. | HE |

| Zacatecas | Mazapil | 2009 | Pollution. | W |

| Health problems. | H | |||

| Environmental damage. | HE | |||

| Omission of information. | LE | |||

| Chalchihuites | 2014 | Displacements. Damage to buildings. | P | |

| Threats. | LI |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camacho-Garza, A.; Acevedo-Sandoval, O.A.; Otazo-Sánchez, E.M.; Roman-Gutiérrez, A.D.; Prieto-García, F. Human Rights and Socio-Environmental Conflicts of Mining in Mexico: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020769

Camacho-Garza A, Acevedo-Sandoval OA, Otazo-Sánchez EM, Roman-Gutiérrez AD, Prieto-García F. Human Rights and Socio-Environmental Conflicts of Mining in Mexico: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2022; 14(2):769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020769

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamacho-Garza, Abraham, Otilio A. Acevedo-Sandoval, Elena Ma. Otazo-Sánchez, Alma D. Roman-Gutiérrez, and Francisco Prieto-García. 2022. "Human Rights and Socio-Environmental Conflicts of Mining in Mexico: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 14, no. 2: 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020769

APA StyleCamacho-Garza, A., Acevedo-Sandoval, O. A., Otazo-Sánchez, E. M., Roman-Gutiérrez, A. D., & Prieto-García, F. (2022). Human Rights and Socio-Environmental Conflicts of Mining in Mexico: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 14(2), 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020769