Abstract

The global expansion of urbanization is posing associated environmental and socioeconomic challenges. The capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, is also facing similar threats. The development of urban green infrastructures (UGIs) are the forefront mechanisms in mitigating these global challenges. Nevertheless, UGIs in Addis Ababa are degrading and inaccessible to the city residents. Hence, a 56 km long Addis River Side Green Development Project is under development with a total investment of USD 1.253 billion funded by Chinese government aid. In phase one of this grand project, Friendship Square Park (FSP), was established in 2019 with a total cost of about USD 50 million. This paper was initiated to describe the establishment process of FSP and assess its social, economic, and environmental contributions to the city. The establishment process was described in close collaboration with the FSP contractor, China Communications Construction Company, Ltd. (CCCC). The land use changes of FSP’s development were determined by satellite images, while its environmental benefits were assessed through plant selection, planting design, and seedling survival rate. Open and/or close ended questionnaires were designed to assess the socioeconomic values of the park. The green space of the area has highly changed from 2002 (8.6%) to 2019 (56.1%) when the park was completed. More than 74,288 seedlings in 133 species of seedlings were planted in the park. The average survival rate of these seedlings was 93%. On average about 500 people visit the park per day, and 400,000 USD is generated, just from the entrance fee, per annum. Overall, 100% of the visitors were strongly satisfied with the current status of the park and recommended some additional features to be included in it. In general, the park is contributing to the environmental and socioeconomic values of the city residents, and this kind of park should be developed in other sub-cities of the city as well as regional cities of Ethiopia to increase the aesthetic, environmental and socioeconomic values of the country, at large.

1. Introduction

Urbanization is increasing globally and subsequently the number of people living in cities is also rapidly expanding [1]. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) also forecasted that in 2030 more than 60% of the world’s population would be living in cities [2]. These evolving cities are responsible for 80% of greenhouse gas emissions [3]. The process of urbanization and associated effects cause climate change, which is endangering critical natural resources in and around cities, posing unprecedented environmental and social challenges, jeopardizing the operation of critical systems, and putting additional strain on local institutions [4].

In order to combat challenges imposed by urbanization, urban green infrastructures (UGIs) are becoming a popular strategy in different parts of the world [5,6]. Green infrastructure (GI) is an interconnected network of multifunctional green spaces that are strategically planned and managed to provide a range of ecological, social, and economic benefits [6,7,8] while mitigating the effects of rapid urbanization and climate change and improving cities’ resilience. Furthermore, UGIs have great role in mitigating the spread of pandemic outbreaks, such as COVID-19, by enhancing air quality, and maintaining physical and mental health while practicing social distancing [9,10]. This is in line with the aim of the 11th goal of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda, stating that cities and human settlements should be inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable [11]. A variety of land use practices and environmental factors influence the benefits of multifunctional greenspaces while challenging biodiversity, vegetation structure, composition, and ecological function [12,13].

Urban parks are integral components of UGI [14], playing a critical role in the provision of urban ecosystem services [12,15,16,17]. There is also a growing consensus that ecosystem service considerations should be incorporated into park planning, policy, management, and design [18,19]. Urban parks have economic, social and environmental benefits, including mitigation of climate change, reduction of heat island effect, the reduction and absorption of pollutants, creation of new niches, the preservation of natural resources and landscapes, biodiversity conservation, the enhancement of the attractiveness and beauty of urban landscapes, the improvement of quality of life, and creation of job opportunities [6,16,20]. The environmental benefits of urban parks to deliver multiple benefits to urban residents depends on the land cover, amount of green coverage and the various types of ecological entities it holds [13,21].

In the city of Addis Ababa, the UGI components are classified into four major sets, namely recreational parks, river and riverside green, urban agriculture, and urban forest. Nevertheless, the rapid expansion of housing construction, the growing density of built spaces, and reshuffling of industrial areas in the peripheral part of the city is negatively impacting these green constituents [6]. Accordingly, the land use of UGI, and urban forest in Addis Ababa decreased by 9.2% and 3.7% from 2003 to 2016, respectively. Furthermore, the city’s park per capita was very small (0.37 m2) compared to Ethiopian UGI standards (15 m2) and the large portion of the city’s population (above 90%) has no access to existing parks within the minimum walking distance thresholds [6].

In order to make Addis Ababa city very attractive, improve its flood discharge capacity and control river pollution, the city administration planned and launched the Addis River Side Green Development Project, that is, the renovation of 56 km of river channels in the city and development of river side GI with a total investment of USD 1.253 billion, funded by Chinese government aid, aiming at maintaining the long-term friendship between China and Ethiopia. As phase one of this green development project, Friendship Square Park (FSP), functioning as a space for important national celebrations and gatherings, and citizens’ daily leisure and recreation, was established in 2018 with a total cost of about USD 50 million by the construction company, China Communications Construction Company, Ltd. (CCCC). The park generally has political, economic, social, cultural and environmental values.

To date, the analyses of UGI reported by several authors [22,23,24,25,26] revealed that UGIs have multiple benefits, such as recreation, improving physical and mental health, and regulating services. However, less reports have been found on the reduction of unemployment and economic benefits of UGI that serve as a smokeless industry (urban tourism), which has a significant role in poverty alleviation of developing countries, such as Ethiopia. In addition, many UGIs lack appropriate planning and urban infrastructure networks, and do not focus on preventing human induced climate changes and lately emerged social health concerns, such as the COVID-19 pandemic [23,24,25,26]. Out of 171 reports on UGI, the vast majority of the research was from the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom. However, there has been limited research from Africa [23]. Friendship Square Park was established with the intentional plan and design of the Prime Minister of the country with huge investments and involves funds and professionals from China. In addition, the park was established in the center of the city to integrate urban infrastructure networks and has a location advantage for enhancing urban tourism. The park can contribute to alleviation of unemployment rate and focuses on the economic benefits of the country from urban tourism. Further, it serves as a reduction mechanism for emerging social health concerns, such as COVID-19, and it has cultural spaces for enhancing social coherence among different nations and nationalities of the country. The research on FSP will increase the research intensity of UGI from sub-Saharan Africa in particular and Africa in general. Therefore, this paper aims to evaluate FSP in light of its social, economic, and environmental contributions to the city of Addis Ababa. Further, it investigates the social values of the square ecosystem services as perceived by users; assesses its economic benefits to the city administration; evaluates the environmental significance of the park and describes the establishment process, plant species composition, richness and survival rates in each physical sections of the park.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Study Area

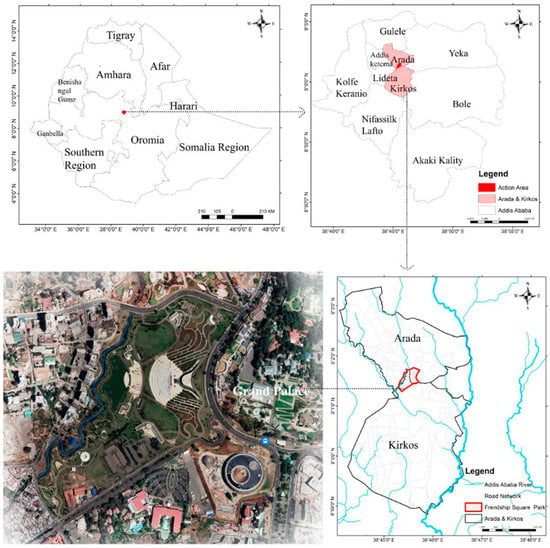

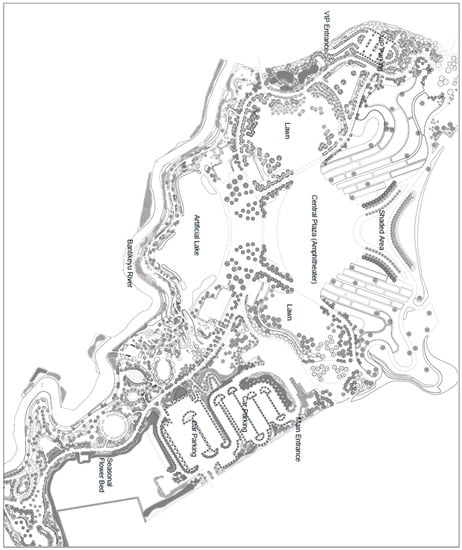

This study was conducted in FSP in the Addis Ababa City, Arada sub-city. The park is found in the upper most central part of Addis Ababa, located at the Bantyiketu river side located between 9°1′10″ N–9°1′35″ N latitude, and 38°45′20″ E–38°45′40″ E longitude and elevation at 2375 m.a.s.l. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location map of Friendship Square Park establishment area.

FSP was selected for this study due to the fact that it has become one of the main urban parks in Addis Ababa since 2018 and its prime location in the central part of the city is drawing significant attention from the city dwellers. Furthermore, the fact that the Square is located very near to the Bantyiketu river has given it higher significance for the study [27].

2.2. Environmental Significance of Friendship Square Park

A forum on urban park restoration at the 4th International Outdoor Recreation and Tourism Trends Symposium in 1995 concluded that, in addition to the socioeconomic significance, environmental values should receive attention in urban park restoration efforts [28].

In this study, the following factors were taken into account in order to study the environmental significance of FSP development. These are: assessment of trends of Land Use Change in the development of FSP, assessment of soil characteristics, planting design, site preparation for planting, source of planting materials, composition and characteristics and their quality features, seedling survival rate enhancing mechanisms, and maintenance and management requirements during the construction period.

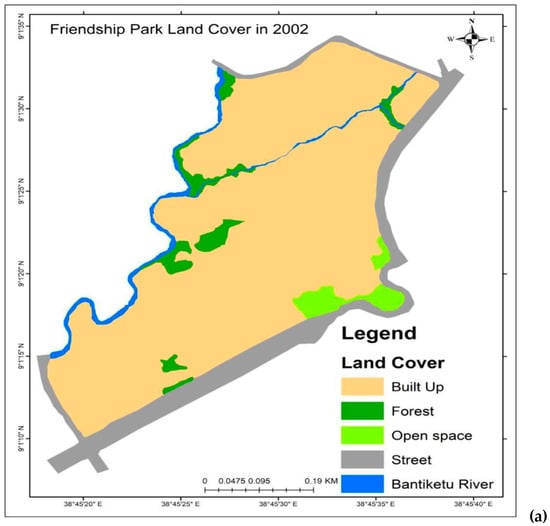

2.2.1. The Trends of Land Use Change in the Development of Friendship Park

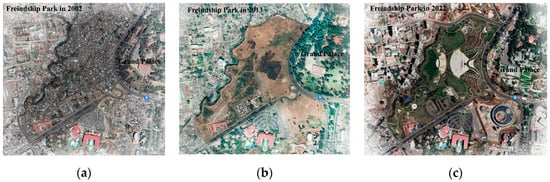

Using ArcGIS 10.8 software, major land use types identified in the process of FSP development were manually digitized from high-resolution aerial photographs taken in 2002, 2013, and 2022. This was performed with the assumption that changes in land use over time provide different environmental services to society, the economy, and the environment. Built-up areas (impervious surfaces), which primarily include residential and school land uses, open spaces, forests (vegetation cover), water body, and bare lands of FSP are identified as the major land uses of the park (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

High-resolution aerial photograph of the establishment area of Friendship Square Park during the years 2002 (a), 2013 (b), and 2022 (c).

2.2.2. Assessing the Soil Characteristics and Site Preparation of Friendship Square Park

During preparation, physical and chemical properties of the soil in the Friendship Square establishment area were tested and analyzed at the Institute of Technology, Addis Ababa University and corresponding measures, such as soil improvement, fertilization, or replacement of borrowed soil, were made to meet the standard requirements. When the chemical properties of the soil, such as acidity, alkalinity or fertility, were not suitable, targeted treatments were also made. The size of planting holes and grooves were determined according to the root system of seedlings, the diameter of soil balls and soil conditions. Planting holes and planting troughs were dug vertically with the upper opening and lower bottom being equal. Base fertilizer was applied at the bottom and top soil or improved soil was backfilled. Planting holes and tank bottoms with impermeable and heavy clay layers were loosened or drained. Dry soil was soaked with the whole before planting and the soil compactness was made less than 1.35 g/cm3, or if the permeability coefficient was less than 10−4 cm/s, measures were taken to expand the tree hole, loosen soil, etc.

2.2.3. Planting Design

Planting design is an important consideration in urban parks because trees are one of the tools for defining outdoor open space while also providing shape and configuration to spatial environments. Many factors need to be taken into account when recommending locations for tree planting [29]. In general, the various landscape design methods applied for Friendship Square Park are referred from Code for Design of Parks GB 51192-2016, Design Specifications of Urban Green Space GB50420-2007 (2016 version), Technical Specification for Planting Roofing Engineering JGJ155-2013, and Drafting Standards of Landscape Architecture CJJ/T 67-2015. With regards to the planting design, the park was divided into different zones whereby the various features in the landscape, such as the river buffer zone, the central amphitheater area, seasonal flower beds and other elements, have guided the planting decisions. Furthermore, climate factors, soil characteristics, environmental conditions, planting space, site location, existing vegetation, aesthetics, land ownership and regulations, social influences, and maintenance requirements are all important requirements to consider when selecting trees [30]. Locally suitable tree species, such as native (indigenous) tree species or tree species that have been successfully introduced, domesticated, and widely used, are among the criteria for selecting appropriate plants for FSP.

2.2.4. Source of Seedlings and Their Quality Features

Based on the planting design decision, different seedling types were obtained from different sources. Seedlings of flowers were purchased from the seedling base of Syngenta and cultivated in the greenhouse. The shrubs were sourced from a nursery at a nearby market. The trees were brought from a wide range of sources, including Hawassa and Sodo mountains in the southern region and the surrounding areas of Addis Ababa, mainly from the Yeka and Entoto mountains. Planting materials/seedlings have the basic quality requirements of robust growth, luxuriant branches and leaves, complete crown shape, normal color, developed root system, no plant diseases and pests, no mechanical damage, and no freezing injury. The criteria for selecting planting materials of the park include locally suitable tree species, such as native (indigenous) tree species or tree species that have been successfully introduced, domesticated and have been widely used. Moreover, plant materials with plant diseases and pests were strictly prohibited. Species and variety names, as well as quantity and quality of the seedlings, were carefully checked before bringing the seedlings to the planting site and were subjected to local plant quarantine. The existing plants in the site were kept in situ according to the requirement of the planting design.

2.2.5. Survival Rate Enhancing Mechanisms of Seedlings

Before planting, tree plant seedlings were trimmed based on local natural conditions to keep the growth balance of the above and underground parts of the tree body. Split roots, roots affected by diseases and pests and excessively long roots of seedlings were trimmed. Suitable planting time was selected for tree planting according to tree species habit and local climate conditions.

After planting, a 10–20 cm high irrigation soil cofferdam was built around the planting hole with its diameter slightly larger than that of the planting hole. The cofferdam was built solid, without leakage, and the relatively steep side slope was provided with a temporary platform. After planting seedlings in the planting pool, the planting soil was 5 cm lower than the pavement finished surface and that of the top elevation of the pool for watering. Well buried and firm triangular, four-corner and row support were carried out according to site conditions and tree specifications. Large-sized trees were planted with ventilation pipes to ensure survival rate.

The planting area was covered with volcanic rocks (particle size 2–3 cm) with a thickness of 5 cm to ensure no soil leakage in the planting area. In the aquatic plant area, the planting boundary on the side facing the water was vertically inserted into the 50 cm long Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) board in the soil for root separation treatment and the PVC board was exposed to the soil layer of 5 cm and not to the water surface.

Watering, bud stripping, tiller removal, branch thinning and shaping, top dressing and fertilization were carried out according to plant habits and growth conditions. Weeding and leveling of the tree stands according to the site conditions were made. To control diseases and pests, biological prevention and control methods, biological pesticides and high-efficiency and low toxicity pesticides were applied. Occurrence of sudden diseases and insect pests were controlled, and prevention methods were taken on time. The green space was kept clean and tidy, dead branches, fallen leaves and weeds were cleaned and removed on time.

2.3. Assessment of the Socioeconomic Importance of Friendship Square Park

To assess the social importance of the park, structured questionnaires consisting of ten questions were designed (Supplementary File S1). Data were collected from 251 park visitors, who were composed of Ethiopians, diaspora and foreigners. The purpose of the social data was to evaluate the degree of satisfaction, cost of the entrance fee, distance of their residence from the park, additional features to be added, the purpose of their visit, importance of the park, and to identify the most exciting part of the park. In order to assess the economic importance of FSP, secondary data were obtained from the park manager. A total of seventeen economic related data were collected from close- or open-ended questions (Supplementary File S2) to evaluate the economic importance of the park to the city administration, society and the country at large.

3. Data Analyses

In this study, both qualitative and quantitative data were used. ArcGIS (geographic information system) was used to develop changes in landscape features of the park establishment area. Using high-resolution images, twenty years of landscape features changes from 2002 to 2022 were generated, beginning with slum settlement and ending with complete transformation into Friendship Square Park. Images of the years 2002, 2013 and 2022 were downloaded from the Google Earth website and georeferenced in ArcGIS 10.7. These years’ data were chosen because they represent significant land use/land cover (LULC) change at the FSP establishment site. While the 2002 image depicts the then existing slum area that had developed over many years, the 2013 image shows the complete demolition of the slum settlements, and the 2022 image portrays the site’s complete transformation into an urban park, FSP. Two procedures were followed for the mapping of LULC, the first one is visual interpretation of images to identify the major LULC classes, while during the second method the image was digitized, and areas were calculated in ArcGIS environment. Furthermore, the change between the different land use classes during different years was calculated using the following formula:

where: ΔC is a change in LULC in percent; Ai is the area coverage of a LULC class in the initial year; Af is the area coverage of a LULC class in the final year.

ΔC = (Af − Ai) × 100

The free trial version of Microsoft Windows Excel 2010, USA was used to analyze the social data. In these data, the percentage of the response of the visitors for each category of questionnaires was presented in graphs. The economic data and the soil analysis results were presented in descriptive forms. Finally, the results, including the seedling survival rate, were presented in the form of tables, graphs, charts and diagrams.

4. Results

4.1. Environmental Significance of Friendship Square Park

Friendship Square Park Land Use Change Trends

A landscape’s potential for providing environmental services is determined by the amount and type of green coverage it has, as well as the various ecological entities it contains. As a result, the result of Friendship Square Park’s land use cover change over time shows that the land cover changed over the course of twenty years, from 2002 to 2022, with varying potential to deliver various ecosystem services.

Thus, prior to 2002, 91.4% of the area was covered by built-up area, dominated by residential land use, whereas in 2013, following the removal of the slum settlement, 61.3% of the total area changed into bare land while 13.6% was naturally developed into vegetation cover. Following the park’s development in 2019, the green coverage of the park increased to 56.1% while the built-up area increased to 35.8%, including the streets inside the park with an additional ecological entity, the water feature, with 6.3% of the total coverage (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Land use change of Friendship Square Park establishment area in 2002 (a), 2013 (b) and 2022 (c).

Thus, FSP not only increased vegetation cover, but also added various ecological entities, such as a grass lawn, a water feature with aquatic benefits, a forest, and others. As a result of these additional ecological entities, the park is now equipped to provide a variety of ecological or environmental services to the community (Table 1).

Table 1.

Friendship Square Park land use change trends from 2002 to 2022.

4.2. Soil Content Analysis

The pH value of the soil was 5–8. The total salt content of the soil was 0.15–0.9 ms/cm under the condition of water to soil ratio of 5:1, 0.3–3 mS/cm under water saturation extraction. Soil organic matter reached 12–18 g/kg, its infiltration was ≥ 5 mm/h, cation exchange capacity ≥ 10 cmol (+)/kg, organic matter 20–80 g/kg, hydrolysable nitrogen 40–200 mg/kg, phosphorus 5–60 mg/kg, potassium 60–300 mg/kg, sulfur 20–500 mg/kg, magnesium 50–580 mg/kg, calcium 4–350 mg/kg, manganese 0.6–25 mg/kg, copper 0.3–8 mg/kg, zinc 1–10 mg/kg, molybdenum 0.04–2 mg/kg and soluble chlorine > 10 mg/kg. When the planting soil did not meet the standards, it was improved and it could not enter the construction site until it met the composition requirements of the planting soil.

4.3. Planting Design and Features of Friendship Square Park

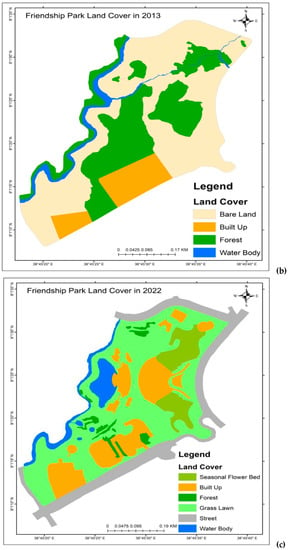

4.3.1. River Buffer and Artificial Lake Area

The water feature area is one of the special features of FSP, with a total area of about 2 ha consisting of seven aquatic plants species, namely Alocasia macrorrhiza, Pontederia cordata, Canna glauca, Nelumbo nucifera, Cyperus papyrus, Cyperus alternifolius, and Nymphaea lotus, with 5.3% species composition and a total of 1707 seedlings. The design harmonized the artificial lake with the existing Bantyiketu river passing along side by locating the lake close to the river. The plants recommended are mainly aquatic plants, aromatic plants, and palms, such as Phoenix reclinate (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Planting design of Friendship Square Park. Areas with black dots indicate the planting areas of seedlings of different plant species.

The other main feature of the park is the central plaza area where the amphitheater is located. Around this area the planting design incorporated decorative trees, such as Spathodea campolunata, Acacia abyssinica and Aurucaria excelsia. These trees, in addition to the aesthetical value, also provide shade to park visitors (Figure 4). In addition, indigenous trees, such as Pdocarpus falcatus, Juniperous Procera and Coffee arabica are also planted in the central plaza area. Ground cover plants in the central plaza area include Pelagotium hortorum, Profusion series, Verbena hybrida, Osteispermum ecklonics, Petunia hybrida, Viola tricolor, and Cynodon dactylon. In addition, the central plaza comprises flowering plants for decoration, such as Agapantus africanus and Zantedechia aethiopica.

Planting around the west side of the park mainly comprises of a large lawn Cynodon dactylon, known as Bermuda grass, covering about 11,747 m2 of area, surrounded by various flowering plants and herbs, such as Agapanthus africanus, Hydrangea macrophylla, Crinum moorei, and including shrubs, such as Bouganvillea glabra, Uibiscous rosasincensis, Nerium oleander, and Rosa chinensis. Large trees in this area are mainly composed of Spathodea campolunata, Grevillea robusta, Acacia retinodes, Jacaranda memosifolia, Juniporous procera, Terminalia Mantalay, and Pinus wallichiana. The results in general show that there is high dominance of exotic decorative plants (Figure 4).

Functionally the eastern side of the park mainly serves as main access for the public and therefore is provided with a vast car parking lot. Accordingly, the plant cover consists of trees, such as Gravellia robusta, Casuarina equisetifolia, Acacia melanoxylon, Acacia retinodes, Spathodea campolunata, Hygenia abysinnica, and Juniperous procera. Furthermore, the area accommodates large number of mixed flowering plants, such as Cuphea ignea, Lantana camara, Cynodon dactylon, Cuphea hookeriana, Pelargonium hortorum, Canna generalis, Zantedeschia aethiopica, Agapnthu africanus, Rosa abysinica, Chlorophytum comosum, and large shrubs, such as Nerium Oleander (Figure 4).

4.3.2. Plant Species Composition, Survival Rate and Its Enhancements Mechanisms

The Friendship Square Park is comprised of 133 different species that are grouped into eight plant types, namely special tree form, evergreen (deciduous tree), palm and around the palm, middle tree and shrub, small shrub and flower, scantentes, flower and water plants (Table 2). The list of all species contains a total of 74,288 seedlings (Table 3). Flowers compose 40 species or 30% of the total plant species, followed by evergreen (deciduous tree) plant type (28 species) and middle tree and shrub (19 species). Flowers occupy the largest species compositions of the park (66.3%) and have large number of total seedlings (49,290), followed by small shrub and flower (9935, 13.4%). Scantentes, special tree form, and water plant possess few numbers of species (three, four and seven, respectively). Special tree form has the least percentage of species abundance (0.7%) and total number of seedlings (502). Water plant type has the highest average survival rate (100%) followed by flowers and palm (98%).

Table 2.

Total number of species, species composition, total number of seedlings, average number of seedlings and survival rate per plant type of Friendship Park.

Table 3.

List of all planted species types, the total number of seedlings per species and each species abundance of Friendship Park.

All species had survival rates greater than 85%. Middle tree and shrub and evergreen tree had the least average number of seedlings per plant type, while scantentes and flower had the highest average number of seedlings per plant type. In addition, the species analysis result shows that there are only 12 (9%) indigenous species that are planted in FSP at different locations (Table 2). The survival rate of large trees was improved through rooting agent, nutrient solution, anti-transpiration agent, scientific pruning, soil balls, planting soil improvement, burying ventilation pipes, and post-scientific maintenance. The survival rate of most plant types was more than 90%.

The hybrid ornamental plant species, Pelargonium hortorum, had the highest percentage of species abundance (9.4%) in the park, which had 6997 seedlings, followed by Zinnia elegans which possessed a species abundance rate of 7.1%. The average species abundance in the park was 0.76% per species. Species that had least species abundance, 1–4 seedlings per species, were Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata, Hypericum monogynum, Ficus elastica, Phoenix canariensis, Carica papaya, Sambucus williamsii Hance, and Vinca major var. variegata. The maximum and the minimum number of seedlings per species in the park were 6997 and 1, respectively.

Based on the total number of seedlings per species and species abundance parameters of the park, the most abundant species in Friendship Square Park were Bougainvillea glabra (2.8%, 2118.1), Verbena hybrid (2.8%, 2121.2), Petunia hybrid (3.0%, 2280), Duranta repens ‘Variegata’(3.9%, 2931.8), Lantana camara (4.3%, 3193), Zantedeschia aethiopica (4.8%, 3543.2), Agapanthus africanus (4.9%, 3665.3), Zinnia elegans (7.1%, 5281.5) and Pelargonium hortorum (9.4%, 6996.8) in their respective order (Table 3). The survival rates of these most abundant species were above 95%. The survival rate of all the plant species ranged from 50–100%. The average percentage of survival rate was 93.4%. The last five species which had low survival rate compared to other species were Sambucus williamsii Hance (50%), Pinus radiate (59.1%), Cordia africana (61.8%), Acacia melanoxylon (68%), and Borassus ethiopium (69.6%). A total of 33 species among 133 had a 100% survival rate. The average plant seedlings per species were 558.5 (Table 3).

4.4. Socioeconomic Benefits of Friendship Square Park

4.4.1. Economic Benefits

The park was completed and opened for visitors on 2 February 2021. The entrance fee was set to be ETB 110 (equivalent to USD 2) and there is no price difference for Ethiopians, the diaspora and foreigners. There are discount possibilities for children and students as visitors and the entrance fee has not increased since it was first set. On average, more than 500 people with diverse age categories visit the park per day and the number of visitors is increasing from time to time. Therefore, the park generates more than ETB 20 million just from the entrance fee per annum.

The park has created a job opportunity for 65 people, which can approximately support about 325 people. The number of visitors is usually high over the weekend as compared to weekdays and visitors usually prefer the dry season. In the park there are about six business centers, most of which are cafeteria services.

Regarding the satisfaction of the visitors, 100% of the visitors are strongly satisfied. Night visitors are satisfied due to available car parking space, the singing fountain that starts, landscape lighting being turned on, river sign pump, and the lake fountain run.

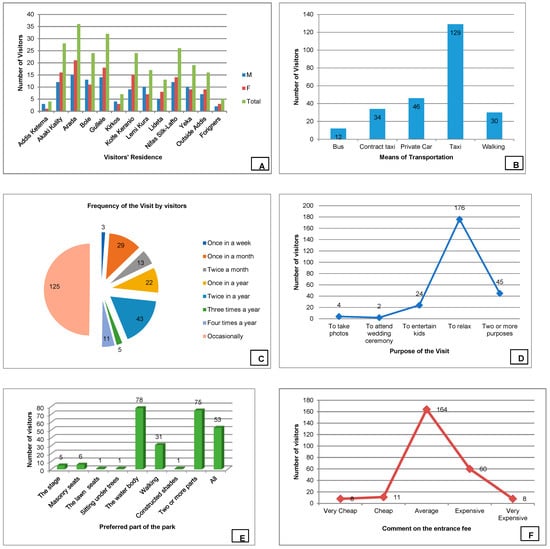

4.4.2. Social Benefits

A total of 251 visitors responded to the questionnaires on social perspectives of FSP, of which 135 (54%) of them were female. As revealed from their response, visitors came from all the sub-cities of the Addis Ababa city administration. There were also visitors who came from other parts of Ethiopia, outside Addis Ababa, as well as foreigners. As compared to other sub-cities, relatively high numbers of visitors were from the Arada sub city, 36 (14%), and the least number of visitors came from the Addis Ketema sub-city (Figure 5A). Most of the visitors, 129 (51%), used normal taxis as a means of transportation to reach the park for the visit (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

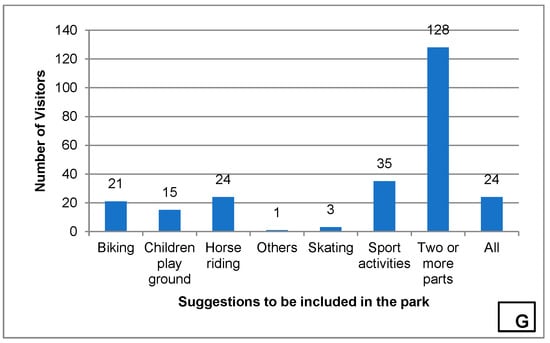

Social perspectives of Friendship Square as revealed from visitors’ responses: (A) visitors’ residences; (B) means of transportation; (C) frequency of the visit by visitors; (D) purpose of visit; (E) preferred part of the park; (F) comment on the entrance fee and (G) suggestions to be included in the park.

Fifty percent of the visitors to the park have no regular visiting plans, and instead visit it occasionally, with only three people planning to visit the park once per week (Figure 5C). Over 70% of the visitors come to the park to unwind (Figure 5D). While 2.1% of visitors appreciated all of the park’s services, one-third of visitors treasured the park’s water body (Figure 5E). More than 65% of the visitors perceived the entrance fee to the park as affordable and average, while some (8%) said that it was expensive or cheap (Figure 5F). Visitors were also polled to determine their preferences for additional park amenities, whereby 30% of them had more than one preference and suggested a children’s playground, sporting activities, biking and skating to be included as additional entertainment. Furthermore, in terms of visitor satisfaction, 100% of the visitors are extremely satisfied with the services provided by the park and their general feedback was very interesting and excellent. Night visitors are more satisfied due to car parking, the singing fountain, and the landscape lighting.

Finally, a few visitors suggested having enough toilets facilities, affordable cafeteria and roadside fast foods, access to internet Wi-Fi, entrance to the park should be very cheap or free to give the chance for the poor, a stage for cultural dance, protections to water body areas to avoid unprecedented risks that may happen to children and elderly visitors, and enough dust bins.

5. Discussion

Parks need to be multifunctional [31]. Similar to the reports of [8,32,33] the results of the assessment revealed that Friendship Square Park, located at the center of Addis Ababa city, plays important social, environmental and economic functions that contribute to the quality of life and enhance the appearance of the city. It provides places for physical activity, space for leisure and recreation, improves social cohesion and interaction, contributes to the social well-being and the health of the community, restores urban ecological environments damaged by human activities and plays a vital role in carbon sequestration and conserving natural resources, such as water and soil [34].

Urban parks are “the lung and oxygen tank of the city”. Specifically, the environmental benefits of parks are pollution control, water management, biodiversity and natural conservation [5]. Consequently, the range of land cover changes of FSP in the last 20 years will bring these values, as there is a 73.5% reduction in the built-up area, while there is a 43% increase in green coverage of the park area. In addition, FSP included various landscape features, such as artificial lake, flower beds and grass lawns. The result of the present study is in agreement with the reports of [35,36]. Moreover, [28] reported that incorporating water features in urban parks greatly helps in modifying microclimate and [37] also discussed that large urban parks have major cooling effects that reduce the urban heat island, i.e., reduce the temperature of their surrounding up to 0.6 to 2.8 °C. In the same analogy, [34] reported that protected areas are an important part of the society, and provide ecosystem services, such as climate regulation and water filtration, which benefit humans with clean air and water and elicit economic benefits.

Friendship Square Park in Addis Ababa has been playing its social roles, such as conducting public and cultural celebrations, hosting regional, national and international meetings and university graduations. It also has an important role in mitigating pandemic outbreaks, such as COVID-19, and others [9,10]. All the visitors were satisfied with the current status of the park, and they found FSP as very interesting and excellent, this is due to the fact that until the present day the city did not have such a type of park. In addition, FSP included various landscape features, such as artificial lakes, flower beds, grass lawns and a cultural amphitheater, which are very attractive for visitors. In agreement with the present study, [38] also categorized the benefits of urban parks as environmental and architectural/aesthetic uses that help in reducing air, noise and sight pollution and in improving air temperature in an urban area, contributing to the physiological and psychological well-being of urban residents, and maintaining green, clean and beautiful environments. Moreover, with the development of urban tourism, modern urban parks, such as Friendship Park, serve not only for local residents but also for foreign visitors.

The FSP as a tourism industry generates more than ~ 400,000.00 USD just from the entrance fee per annum which significantly contributes to the GDP of the country. The park has created a direct job opportunity for 65 people, who can approximately support about 325 people, and it also indirectly created job opportunities for many people around the park. In the park there are about six business centers, most of which are cafeteria services. Moreover, the result of the present study revealed that the development of the park has encouraged urban tourism, by serving not only the local residents but also for foreign visitors. Tourists have granted access to the park and investors are allowed to build lodges and other tourist facilities to enhance enjoyment of visitors in the park. As reported by [34], protected areas are important parts of the society which provide ecosystem services, such as climate regulation and water filtration, that benefit humans with clean air and water and eliciting economic benefits.

The assessment of planting design revealed that there are 133 plant species in FSP; however, indigenous plant species account for only 9% of the total species composition, while exotic plants account for the remaining 91%. Furthermore, the planting design evaluation revealed that the main concept used to select plants was the aesthetic value of the park, which contributed to the decision to select exotic decorative plants over indigenous trees. As a result of this decision, the park’s potential to provide various environmental ecosystem benefits to protect the soil and biodiversity is reduced [35]. By nature, indigenous trees have the ability to balance nature, provide food and shelter for biodiversity, resist pests and diseases, require little maintenance gardening, and serve as the foundation for native ecosystems [39].

The range (85–100%) and average (94%) seedling survival rate in the FSP was much higher compared to other related parks. For example, the average survival rate of tree species seedlings of Mt. Elgon in Kenya ranged from 5.7% to 74% and the average survival rate was below 50% [40] and the national average survival rate of seedlings in Kenya was 67% [41]. As reported by [42], tree seedling survival rates ranged from 35 to 74% in the Tigray region. Seedling survival rate was considered as an indicator of forest regeneration potential [43]. Climatic factors, such as drought, heat and frequent windstorms and time of planting have a major effect on plantation success. Poor management, inadequate supervision, grazing, inflicted damages, uncontrolled burning of field debris, pests, soil type and texture have been reported to affect plant species seedling survival rate, species composition, abundance, and structure [40,42,43,44,45,46]. Therefore, the application of different seedling survival rate enhancement mechanisms markedly improved the survival rate of seedlings planted in FSP.

Visitors of FSP suggested different additional features to be included in the park for its better operation. According to the recommendations of [31], Stanley Park in Canada should have playgrounds, water features, squares, plazas, gardens, schools, parking, streets, waterfronts, riverbanks, courtyards, bridges, piers, sports, forest, wetlands, campus, corporate, residential, post-industrial, roofs, cultural heritage, restorations and skate areas. Most of the reports were in agreement with the general comments given to Friendship Park by the majority of the visitors.

The incorporation of additional features and recreational centers of the park can attract more visitors, thereby increasing the entertainment of the visitors and the income of the park. As reported by [31] during the COVID-19 pandemic, Stanley Park has experienced exponential increases in the volume of users as people have sought ways to enjoy green spaces and their benefits safely. Similarly, Friendship Park in Addis Ababa has been playing its social roles, such as conducting public and cultural celebrations, hosting regional, national and international meetings and university graduations and will help in mitigating disease pandemics, such as COVID-19 and others.

In line with the present study, [31] conducted an on-site survey of tourists to investigate their perception, level of satisfaction, possible inadequacies, and suggestions regarding potential therapeutic plants in Stanley Park. The overall satisfaction level of visitors and their dependency on these therapeutic landscape components are high. The inadequacies are relatively simple vegetation structure and lack of wetland plants. People enjoy the beautiful scenery in urban parks and are provided with health benefits. Likewise, [32] confirmed that exposure to urban forest parks enables people to carry out more physical activities, which can significantly prevent obesity and decrease the incidence of chronic medical conditions. Landscape design that focuses on the positive effect of plants on health improvement in urban forest parks provides strong ornamental and convalescent functions, which have become increasingly important and irreplaceable for urban residents. In Canada and worldwide, [47] explained that people are increasingly aware of the importance of urban parks as essential places for conservation, recreation, and education, as well as for people’s mental and physical well-being. They also promote diversity, inclusiveness, and social cohesion by bringing communities together in common places for shared goals.

6. Conclusions and Future Prospects

The study attempted to assess FSP in terms of its environmental and socioeconomic contribution to Addis Ababa city. Further, it investigated the social values of the park’s ecosystem services as perceived by users; evaluated the park’s economic benefits to the city administration; and described the establishment process, plant species composition, richness, and survival rate and its enhancement mechanisms in each physical section of the park. The findings revealed that, following the park’s development in 2019, the park’s green coverage increased to 56.1%, while the built-up area decreased to 35.8%, including the streets within the park, with the water feature accounting for 6.3% of the total coverage. The park is currently delivering various environmental, social and economic benefits. As suggested from the park visitors, there is a need to include additional features for consideration in future development of parks. In addition, high consideration should be given to the enhancement of endemic and indigenous plants which are vital for the environment, soil and water conservation process. The Chinese construction company, China Communications Construction Company, Ltd. (CCCC), is also interested in constructing this kind of UGIs in other parts of the city or Ethiopia at large.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su141912618/s1. Supplementary File S1. Questionnaires to collect data on the social benefits of Friendship Square Park services as perceived by users. Supplementary File S2. Questionnaires prepared for the economic issues and inputs of Friendship Square Park.

Author Contributions

D.G., T.G. and K.A. performed the data analysis and wrote the draft manuscript. S.D. reviewed the manuscript and gave inputs, comments and suggestions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Friendship Square Park contractor, China Communications Construction Company, Ltd. (CCCC) partially supported this write-up.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials applied for the research are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We the authors, acknowledge the Friendship Square Park administrators for providing secondary data regarding the economic benefits of FSP and those park visitors involved in giving response to questionnaires for the social data. We also thank Su Wu and Zhang Like who are the staff members of the China First Highway Engineering CO., LTD (CFHEC) and were involved in providing the planting design of the park, the planting materials species composition and their source, and also for covering Article Processing Charges (APC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, G.; Coseo, P. Urban park systems to support sustainability: The role of urban park systems in hot arid urban climates. Forests 2018, 9, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Urbanization Prospects. The 2014 Revision Highlights. Available online: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/publications/files/wup2014-highlights.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Grêt-Regamey, A.; Celio, E.; Klein, T.M.; Hayek, U.W. Understanding ecosystem services trade-offs with interactive procedural modeling for sustainable urban planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.J.; Meyer, J.L. Streams in the urban landscape. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001, 32, 333–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.S.; Zhirayr, V. The benefits of urban parks: A review of urban research. J. Nov. Appl. Sci. 2013, 2, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Azagew, S.; Worku, H. Accessibility of urban green infrastructure in Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia: Current status and future challenge. Environ. Syst. Res. 2020, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space public health and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Larson, L.; Yun, J. Advancing sustainability through urban green space: Cultural ecosystem services, equity, and social determinants of health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. He. 2016, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Pan, S. Urban vegetation slows down the spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in the United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL089286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Z.S.; Barton, D.N.; Gundersen, V.; Figari, H.; Nowell, M. Urban nature in a time of crisis: Recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP (2015). Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem Services in Urban Areas. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, B.; Kroll, F.; Müller, F.; Windhorst, W. Landscapes’ capacities to provide ecosystem services-a concept for land-cover based assessments. Landsc. Online 2009, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talal, M.L.; Santelmann, M.V. Plant community composition and biodiversity patterns in urban parks of Portland, Oregon. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesura, A. The role of urban parks for the sustainable city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E. Urban Landscapes and Sustainable Cities. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hoehn, R.E.; Crane, D.E.; Stevens, J.C.; Walton, J.T.; Bond, J. A ground-based method of assessing urban forest structure and ecosystem services. Arboric. Urban For. 2008, 34, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenasso, M.L.; Pickett, S.T. Urban Principles for Ecological Landscape Design and Management: Scientific Fundamentals. Cities Environ. 2008, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibes, D. American environmentalism and the city: An ecosystem services perspective. Cities Environ. 2011, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.B.; Van Den Bosch, M.; Maruthaveeran, S.; van den Bosch, C.K. Species richness in urban parks and its drivers: A review of empirical evidence. Urban Ecosyst. 2014, 17, 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibes, D.C. Integrating ecosystem services into urban park planning and design. Cities Environ. 2016, 9, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kabisch, N.; Qureshi, S.; Haase, D. Human-environment interactions in urban green spaces: A systematic review of contemporary issues and prospects for future research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.; Zingoni de Baro, E.M. Green Infrastructure in the Urban Environment: A Systematic Quantitative Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.; Lee, D. Effectiveness of Green Infrastructure Location Based on a Social Well-Being Index. Sustainability 2021, 13, 79620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C.M. Urban Green Infrastructure for Poverty Alleviation: Evidence Synthesis And Conceptual Considerations. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 710549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, J.Z.; McPhearson, T.; Matsler, M.A.; Groffman, P.; Pickett, T.A.S. What is green infrastructure? A study of definitions in US city planning. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2022, 20, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worku, Y.; Giweta, M. Can We Imagine Pollution Free Rivers Around Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia? What were the wrong-doings? What action should be taken to correct them? J. Pollut. Eff. Control 2018, 6, 228. [Google Scholar]

- Gobster, P.H. Visions of nature: Conflict and compatibility in urban park restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 56, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Xiao, Q.; McPherson, E.G. A method for locating potential tree-planting sites in urban areas: A case study of Los Angeles USA. Urban For. Urban Green. 2008, 7, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trowbridge, P.J.; Bassuk, N.L. Trees in the Urban Landscape: Site Assessment, Design, and Installation. John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.W.; Xieab, Z. Therapeutic plant landscape design of urban forest parks based on the Five Senses Theory: A case study of Stanley Park in Canada. Int. J. Geoheritage Park 2022, 10, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shen, Y. The impact of green space changes on air pollution and microclimates: A case study of the Taipei metropolitan area. Sustainability 2014, 6, 8827–8855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World Forest: Forest Pathways to Sustainable Development; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Winkle, C. African Parks. African People. An Economic Analysis of Local Tourism in National Park. Master’s Thesis, Duke University, Arusha, Tanzania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Negash, L. Ethiopias Indigenous Trees; Addis Ababa University, Press: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tukur, R.; Adamu, G.K.; Abdulrashid, I. Indigenous trees inventory and their multipurpose uses in Dutsin-Ma area Katsina State. Eur. Sci. J. 2013, 9, 288–300. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Wu, F.; Dong, L. Influence of a large urban park on the local urban thermal environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauleit, S.; Duhme, F. Assessing the environmental performance of land cover types for urban planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 52, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina, I.; Hanita, N.M. The Contribution of Ornamental Plants for Birds’ Food and Shelter in Urban Forest Parks (Case Study: Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong, Selangor). Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Masabe, P.W.; Hitimana, J.; Mbeche, R.M.; Matonyei, T. Seedling Survival Levels under Plantation Establishment for Livelihood Improvement Scheme and Implications for Conser-vation of Mt. Elgon Natural Forest Ecosystem, Kenya. Res. J. For. 2020, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kisyula, F.M.; Eric, K.; Peter, S. Tree survival in forest plantations established under plantation establishment and livelihood improvement scheme (PELIS) in Kericho County, Kenya. Res. J. Agric. For. Sci. 2018, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Abrha, G.; Hintsa, S.; Gebremedhin, G. Screening of tree seedling survival rate under field condition in Tanqua Abergelle and Weri-Leke Wereda’s, Tigray, Ethiopia. J. Hortic. For. 2020, 12, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rank, R.; Maneta, M.; Higuera, P.; Holden, Z.; Dobrowski, S. Conifer Seedling Survival in Response to High Surface Temperature Events of Varying Intensity and Duration. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 4, 731267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repáč, I.; Tučeková, A.; Sarvašová, I.; Vencurik, J. Survival and growth of outplanted seedlings of selected tree species on the High Tatra Mts. windthrow area after the first growing season. J. For. Sci. 2012, 57, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhbaatar, G.; Ganbaatar, B.; Jamsran, T.; Purevragchaa, B.; Nachin, B.; Alexander Gradel, A. Assessment of early survival and growth of planted Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) seedlings under extreme continental climate conditions of northern Mongolia. J. For. Res. 2020, 31, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, Z.; Chuyong, G.; Evangelista, P.H.; Yosef, M. Vascular Plant Species Composition, Relative Abundance, Distribution, and Threats in Arsi Mountains National Park, Ethiopia. Mt. Res. Dev. 2018, 38, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.L.; Graefe, A.R.; Benfield, J.A.; Hickerson, B.; Baker, B.L.; Mullenbach, L.E.; Mowen, A.J. Exploring the conditions that promote intergroup contact at urban parks. J. Leis. Res. 2021, 53, 426–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).