Abstract

The positive effects of corporate social responsibility (CSR) on professional sports organizations’ (PSO) sustainable development have been studied in developed markets, e.g., the major four leagues in North America. To assess if CSR has similar effects on the emerging market, this study collected 373 questionnaires among the Chinese Basketball Association (CBA) fans. The descriptive statistical results verified consumers’ positive responses to CSR in their favorite clubs in enhancing their team identification, loyalty, and purchase intentions of game tickets. There existed a strong relationship between team identifications and the clubs’ sustainable development. However, the results of the structural equation modelling indicated that the relationship between CSR and the clubs’ sustainable development was weak. The results indicated that fans generally considered a CBA team’s CSR effort as important, but the importance was not proportional to CSR-related team identification or the clubs’ sustainable development. Moreover, the lack of structural validity within each construct calls for more research frameworks and questionnaire designs for CSR investigations in the context of the emerging market. The practical implication of this study was that clubs with financial difficulties were only suggested to do what they could afford to do in CSR activities rather than get involved more than they could bear.

1. Introduction

While playing professional sports is a means of pursuing spiritual enjoyment [1], the sports business should be considered as a part of society and contribute to the local community [2]. Professional sports are becoming ever more active in CSR as they grow in number in order to obtain a competitive edge and increase earnings [3,4,5,6,7]. This is especially important in the competitive business environment of the sports industry, nowadays [8]. In a study of business sustainability, 93% of the 766 CEOs participating in the Global Compact declared CSR as an essential component for their organizations’ future success (UN Global Compact-Accenture, 2010). This makes it even more crucial for researchers to discuss how professional sports organizations (PSOs) participate in CSR to achieve sustainable development.

Sustainable development is mainly interpreted as a national (or global) goal, but there is a growing discussion about ‘sustainable cities’, ‘sustainable sectors’, and ‘sustainable businesses’ [9]. This shows that the concept of organizational sustainability is multifaceted and inextricably linked to urban development, sectoral development, and business development. The market demand of professional sports makes [10] business development especially important for its sustainability. CSR in sports, according to Filizöza and Fiúneb [11], is a way for organizations to align their values and behaviors with those of their stakeholders. This leaves the way in which PSOs achieve sustainable development open for more exploration. As the sports industry is an important part of the economy and society [12,13], professional sports are expected to participate in socially responsible and sustainable business practices [7,14,15]. To attain a competitive advantage, the traditional resource-based models minimize the teams’ weaknesses, threats, and opportunities and enhance their internal and external strengths [16]. It can be helpful to gain attractiveness by working according to the environmental model of competitive advantage [16]. However, consumers’ positive responses to CSR activities cannot be taken for granted. Kao, et al. [17]’s study on Chinese companies showed that only non-state-owned enterprises had favourable responses.

Research on the CSR of PSOs based on developing markets is limited [7,15,18]. The professional sports system in China has just undergone a reform that marked a transition from state-led to league-led management in some sports [19,20]. The Chinese Basketball Association (CBA) league is a good example [21]. During this transition period, the CBA clubs have gone through a chaotic period with match fixing, black whistles, strikes for pay, etc. [22,23,24,25]. Only the clubs that conform to the changes in business rules survive sustainably [26,27]. Does CSR help sports clubs compete in this new market-oriented environment? Will consumers respond positively to the clubs’ CSR initiatives? If yes, to what extent are the CSR activities helpful for the CBA clubs’ long-term success in the newly reformed regime? This research studies the relationship between CSR involvement and CBA clubs’ sustainable development, with team identification as a moderating factor.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 presents the literature review, especially on PSOs. To analyse the mechanism of these impacts, we present the effect of CSR on team identification in Section 3 and the relationship between team identification and the clubs’ long-term business success in Section 4. According to the findings of the existing studies, we develop our hypotheses. In the research method, we present our research design, i.e., sample selection, variable measurement, and statistical indicators, to verify these hypotheses. Then, we discuss their meaning and conclude at the end of this paper.

2. Literature Review

2.1. CSR in the Business Environment

The notion of CSR had evolved long since the early 1950s [28], when Bowen [29] launched the first comprehensive discussion of business ethics that considered social responsibility. After two and a half decades of definition development [30], Carroll [31] finally defined CSR as “the social responsibility of business encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that society has for organizations at a given point in time”, and later, Carroll [32] structured CSR as a four-staged pyramid form in replacing the term of “discretionary” by philanthropic issues. Meanwhile, the public increasingly were expecting companies to act ethically, socially, and responsibly beyond the legal requirements [28,33,34].

CSR has become one of business’s most orthodox and widely accepted concept [33,35]. Besides Carroll’s most well-known four-stage model, there were also other models of CSR, e.g., based on economic, legal, ethical, and interdisciplinary domains [36], or as community relations, diversity, environment, employee relations, human rights, and media-specific CSR activities [37]. International organizations (UNGC, IOS26000, etc.) and government policies proposed CSR initiatives and regulations that required companies to satisfy their self-interest and fulfil their social responsibility in the competitive marketplace [38,39].

For decades, studies devoted to discussing the influencing factors and implementation results in different industrial contexts noted that CSR was used as a strategic tool for companies to enhance their brand image and increase their competitive advantage, especially in industries such as automotive [40], food [41], oil [42], etc. CSR activities and disclosure were regular practices in large companies’ operations [43,44], and they were essential to their brand strategy [45]. CSR’s growing importance in business is closely related to social development [46]. Although the relationship between CSR and sustainable corporate development is still inconclusive [47], various research has already validated the strong relevance between CSR and corporate identity [48,49]. Other studies have verified the enhancement effect of corporate identity on marketing performance [12,50].

2.2. CSR in the Professional Sports Environment

Before the 1990s, CSR concepts were rarely implemented or applied in the professional sports industry [51], and they have only recently gained traction [52]. Through the “barbarian growth” stage of professional sports, some games were played unethically (black whistles, violence, gambling, etc.) to reap short-term profits [13,53,54,55]. This seriously affected the reputation and long-term benefit of the organization [51,56]. With broader media coverage of the clubs’ activities in and out of the competition court, especially during the age of social media, the sports clubs’ CSR initiatives drew the public’s attention, positively impacting consumers’ patronage intentions [57,58]. Therefore, both internal drivers from the club and external drivers from the league, especially the latter, motivated sports organizations to deliver CSR efforts [53,59,60].

Professional sports enterprises, leagues, teams, and athletes were usually influential social agents [53]. Top sports clubs might have domestic or/and international consumers [52], and they could have economic and cultural significance in social development [13,61]. Value-driven or/and strategic-driven bosses and managers seek to address these issues by doing something for the community, the society, and the corporate [59,60,62]. The focus was not only on ethics and the pursuit of profit [52], but also on creating long-term business and social values [14,18,26,63]. The relationship between CSR and the long-term success of a professional sports club can be considered from different points of view, e.g., spectator attitude, behavioral intentions, and fans’ relationships with the club, etc. [2]. The most known factors to understand the mechanism of CSR effectiveness are team image, identification, loyalties, etc. [64].

As a newly developed brand (since 2017) reborn from a semi-market regime, the Chinese Basketball Association (CBA) remains in its infancy stage in the market environment [65]. Nevertheless, stakeholders expect their favorite team to engage in CSR activities [63]. To the best of our knowledge, research on the customers’ reactions and the influence of CSR efforts on the teams’ long-term success is scarce, if not absent. If we want the stakeholders of CBA clubs to accept CSR quickly, it is important to understand the relationship between CSR and the teams’ long-term success.

2.3. Relationship between CSR and Professional Sports Organizations’ Sustainable Development

The CSR discourse in professional sports has largely focused on measuring CSR performance [7,66], which has led professionals to deploy and measure CSR activities using Carroll’s model of four dimensions (economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic). For example, Şirin and Döşyılmaz [67] investigated Turkish clubs’ fans’ perceptions towards the clubs’ social responsibility. They used Carroll’s four-dimensional model to design the social responsibility components of professional sports clubs and obtain fans’ responsibility preferences so as to deploy CSR activities with a purpose. In a survey on the design of social responsibility indicators for PSOs, Chen [5] noted that the CSR related to sports organizations was evaluated on four key dimensions of CSR (economic, legal, ethical, and charitable), and these were obtained to improve the reputation of organizations, increase competitive advantages, and reduce risks. These studies all explain that the participant CSR in PSOs is conducive to obtaining competitive resources and maximizing interests.

Sustainable development is crucial for the survival and long-term development of enterprises [46,68], and the diversity of sustainability concepts has influenced the discussion of their contributions to the sustainability of corporate activities [9,17]. Professional sport is more than just a social institution [7], and professionals believe that its commercial character entails the need to implement CSR [69,70]. Sports sustainability is a new business-driven concept to create and increase social and business value [14], and the involvement of professional sports teams in CSR efforts plays an important role in the impact of league environmental sustainability [59]. The CSR theme area of professional sports overlaps with the goal of sustainable development. Therefore, the importance of social responsibility as a means to create sustainable business development is heightened.

However, in China’s professional sports environment, how PSOs provide and meet the needs of consumers has become an important issue [63,71,72], especially after the reform of the sports system (comprehensive market-oriented development). Therefore, the concept of sustainable development in this study can be understood as business sustainability. In addition, Walker and Parent [55] mentioned in their study that fans, as an important stakeholder group, were an important factor in maintaining the long-term development of PSOs. The involvement of PSOs in CSR has embedded sustainability in consumer responses [8,64,73]. In general, professional sport games are high-frequency and low-cost products [74]; the consumers’ behaviors could be sensitive to their favorite team’s CSR. In reference to Walker and Parent [55] and Jung [64], we included consumer purchasing behavior and team loyalty as the items to examine sustainability.

The CSR model based on Carroll’s four dimensions, previous theories, and empirical evidence show that the more positive the CSR perception is, the greater an organization had the opportunity to achieve sustainable development. In order to make the CSR efforts of China’s PSOs obtain more positive reactions from consumers, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Stakeholders’ perceptions of the CBA clubs’ CSR involvement and contributions to society can have a positive influence on their business sustainability, including: economic responsibility (H1-1), law responsibility (H1-2), ethical responsibility (H1-3), and philanthropic responsibility (H1-4).

2.4. Impact of CSR on Team Identification

Corporate identity can be described as “who the organization is” [43], while CSR can be used to differentiate from competitors [39]. In a literature review by Otubanjo [49], different notions of corporate identity defined different points of view for CSR, i.e., CSR as “what is socially expected of the firm”; “what the firm does for stakeholders”; “ethical business practices”; and “a managerial and strategic business activity”. A study by He and Balmer [75] validated the link between positive corporate identity management and improved corporate image in the short term and corporate reputation in the long term. Balmer and Greyser [12] proposed that corporate image could be considered a direct consequence of corporate identity and that a strong relationship between corporate image and customers’ trust has been validated [76]. It is quite logical to find the link between the corporate identity and the customers’ trust and loyalty [77,78].

In the sports industry, team identity gives fans a feeling of belongingness and provides a buffer from depression or alienation [79]. The team identification makes the fans share the glory and satisfaction with their favorite team’s performance [80]. During difficult times, team identification leads fans to attribute more causes of low performance to external factors and to maintain or even increase their support [80,81]. Farquhar [82] and Tsiotsou [83] found that team image and fans’ general impression of their supporting team as a personality which reflected their self-image and core values were also positively related to team identification [80], and a better team image led to souvenir purchase intentions [2,57,84]. Another study has confirmed the relationship between the team image and the fans’ loyalty, which means that they are stable even during low-performance periods [85]. Concerning the factor of team image, the strong relationship between it and team identification has been validated [2] and quantified with r = 0.89 [64]. We use “team identification” as the pivotal factor to mediate the effect of CSR on PSC’s sustainable success.

The study of Walker and Kent [6] considered team identification as an independent factor from the CSR and found that combining them promoted the team’s good reputation and the consumers’ purchase intentions. Meanwhile, Ullah, et al. [86] confirmed that with the intermediate factor of spectators’ pride, the CSR perception of spectators could positively influence their team identification. Referring to these studies, we find that CSR can significantly enhance the team identification of fans; we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Stakeholders’ perceptions of CBA clubs’ CSR initiatives can reinforce their team identification, including: economic responsibility (H2-1), law responsibility (H2-2), ethical responsibility (H2-3), and philanthropic responsibility (H2-4).

2.5. Relationship between Team Identification and Professional Sports Organizations’ Sustainable Development

Studies in South Korea [87] and China [88] have shown that CSR perception combined with team identification can positively influence a team’s brand equity. Another study, also in South Korea [89], showed that, mediated by ad contents’ information, entertainment, or irritation values to impress the public, team identification can positively affect purchase intentions. Jung [64] investigated how CSR influenced perceptions of team image, team identification, and the team loyalty of fans in a mature market by throwing light on the “four major leagues” in North America (MLB, NBA, NFL, and NHL). With the same explaining factors, other studies by Lee, Shonk, and Bang [2] and Trivedi [90] have also assessed the customers’ reaction to CSR activities. A study by Latif, et al. [91] found that CSR could improve the employees’ performance with the mediating role of team identification. While investigating the consumers’ behaviors, some studies considered team identification as an independent factor from CSR, and their combination promoted the teams’ good reputation and the stakeholders’ intentions [6], while others considered it as at least part of the consequence of the consumers’ perception of CSR [86].

As mentioned in Section 2.4, team identification can influence the fans’ attribution of winning or losing causes to internal or external factors and thus influence their long-term support to their favorite team [80]. We therefore set H3 of our research as:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

CBA clubs’ identifications are closely related to their sustainable development.

As for CSR issues, referring to the results of the existing studies [64,80,89,92], team identification could influence the CSR’s effects on the teams’ long-term success. Between highly and lowly identified fans, to assess if they have different reactions to CSR on clubs’ sustainable development, we set following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

CBA clubs’ identifications play a moderating role between CSR and their business sustainability, including: economic responsibility (H4-1), law responsibility (H4-2), ethical responsibility (H4-3), and philanthropic responsibility (H4-4).

2.6. Research Model

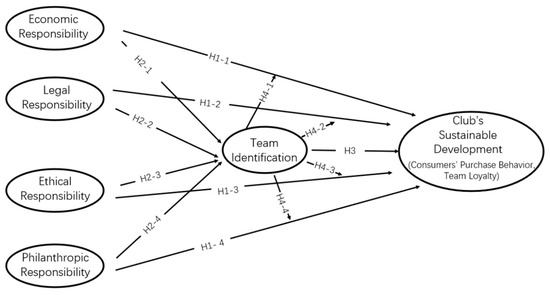

With these hypotheses, the research model of this study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of links between CSR and clubs’ sustainable development.

3. Methods

This study launched a survey among CBA leagues’ fans on (i) their awareness or opinions of the importance of the CSR efforts of their favorite team and (ii) their purchase intention and loyalty related to their favorite team’s hypothetical CSR efforts. We assessed the respondents’ direct opinions with descriptive statistics. For CSR awareness, corporate identification, and business sustainability, the structure within each construct and the relationships between them are further explored with relational analysis methods, e.g., exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the structural equation model (SEM), regression methods, etc.

First, we used descriptive statistical methods to evaluate the respondents’ direct awareness of CSR’s importance, CSR-related team identification, and CSR-related clubs’ sustainable development (H1, H2, and H3). Then, after checking the inner structure coherence of each construct with EFA, we used the SEM to assess the fitness of the research model conceived according to the theoretical framework and validated studies (H1 and H2). Finally, to assess the moderating effect of team identification, we planned regression methods to see if the product of CSR and team identification is closely related to clubs’ sustainable development (H3 and H4). We used SPSS 28.0.1.0 for data analysis.

To precisely understand these results, we contacted some respondents for the reasoning behind their answers and have taken them into account in our discussions.

3.1. Questionnaire Design

Similar to other similar studies [64,73], the questionnaire begins with a demographic survey of the respondents with several variables such as gender, age, marital status, income, education level, etc. This part of the questionnaire is made up of nine multiple-choice questions. This helps us to know the demographic information about the respondents.

The CSR part of our questionnaire was conceived according to reference research in this area [31,32,93] and our preliminary study on the CSR development in China and its characteristics in professional sports organizations. Like the pyramid structure of Carroll’s study (1991), our CSR questionnaire in this study is composed of four subscales, respectively, in economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic aspects, with 28 items in total.

The CSR-related corporate identity part of our questionnaire is adapted from a validated handbook table [94] and from a similar study on North American professional sports organizations [64], which were initially from the investigation of Mael and Ashforth [95]. The corporate identity part of our questionnaire includes 7 items.

The CSR-related business sustainability questionnaire studies customers’ behaviors and their loyalty to PSOs, referring to investigations in mature sports leagues, e.g., the four major leagues in North America [64,96], and designed the questions principally according to the opinions of the managing experts of the clubs interviewed in our previous study. The sustainable development part of our questionnaire includes 6 items. The questionnaire is provided in Appendix A. All CSR-related items were evaluated with a five-point Likert scale.

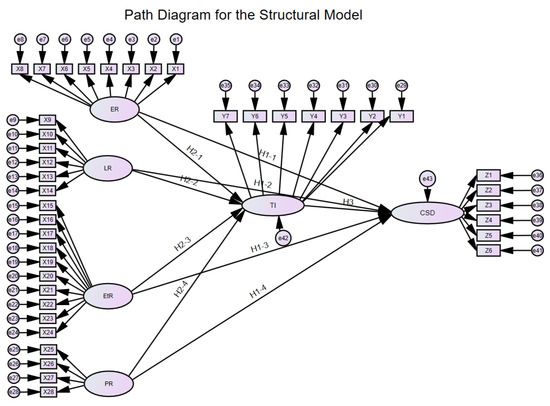

As for the illustration of the individual items of the questionnaire, we obtained the path diagram with AMOS SPSS for the evaluable relationships (H1, H2, and H3 with their sub-hypotheses) in the structural model, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

AMOS SPSS output of the path diagram for the structural model, where ER: economic responsibility; LR: legal responsibility; EtR: ethnical responsibility; PR: philanthropic responsibility; TI: team identification; CSD: clubs’ sustainable development; X1~28: CSR items; Y1~Y7: team identification items; and Z1~Z6: clubs’ sustainable development items. e1~43: residual error of each item. H1-1~H3: hypothetical links.

3.2. Statistical Setting

Within each construct of this questionnaire, the reliability was tested by Cronbach’s alpha values; the threshold of 0.7 is taken as evidence of reliability [97]. The statistical analysis of the responses to our questionnaire includes descriptive statistics, EFA, CFA, and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Following the protocols in the handbook of Hair JR, Black, Babin, and Anderson [97], the descriptive statistics included the usual parameters as mean and standard deviation values and the percentage distribution of different answers. In measuring each item’s factor loading, the EFA with VARIMAX rotation was used to check whether each item was relevant to only one factor. The items’ factor loadings below 0.5 were ignored. After measuring various fit indices, including the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sample adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity Chi-square and significance level, CFA was used to check if this model could well fit the relationships between different CSR constructs, corporate identity, and the corporate’s sustainable development.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

After sending the survey to a CBA fans’ online community, 400 respondents accepted our survey for 5 days. Among them, 12 were coaches, players, or bureau employees. The other 388 respondents were consumers of CBA games. A total of 15 responses were deleted for the monotonicity (same choice for more than 25 questions) in their answers which made correlation analysis impossible.

Among the 373 surveys, 194 (52%) respondents were male, and 179 (48%) were female. A total of 11 respondents (3%) were less than 18 years old, 223 (60%) were between 18 and 30 years old, 116 (31%) were between 31 and 50 years old, and 23 (6%) were more than 50 years old. In addition, 222 (59%) were not married, 7 (2%) were divorced, and the others were married. Regarding educational background, 336 respondents (90%) had a bachelor’s degree. A total of 245 (66%) of them had a monthly income more than the median income (about 700 dollars using purchasing power parity) in China in 2021 (National Bureau of Statistics of China). An amount of 269 (72%) respondents had their favorite team, and 104 (28%) of them had changed their favorite teams. In total, 299 (80%) respondents watched at least one CBA game on television, while 88 (24%) watched more than ten CBA games each year. Only 20 (5%) of them went to the arena to watch more than ten CBA games each year, and 258 (69%) have never watched any CBA game in the arena.

The respondents active in the fans’ online community were, in general, those who were young with higher degrees and incomes. They can be considered as the most active CBA fans at present and the most likely to stay loyal in the long term, even if most fans now can only watch most of the CBA games from TV broadcasts. The interview of our expert practitioners in the CBA confirmed that basketball fans’ consumption of CBA products (games, peripheric products, magazines, etc.) was much lower than NBA products. CBA games were generally lower in in-arena attendance, TV ratings, and online activity. Almost all teams are underfunded and supported by prominent local companies.

As shown in Table 1, the score 4 is the most chosen for the importance of CSR and 5 for items concerning team identification and the clubs’ sustainable development. The scores 1 or 2 have been hardly chosen for any question. For almost all questions, positive answers (choice of 4 or 5 points) accounted for more than 60% of the total. Therefore, in concordance with other studies on CSR in professional sports [58,64,69,90], most consumers have a high level of CSR awareness and gave positive responses to the hypothetical CSR involvement, especially in items of CSR-related team identification. The only exception is the question concerning the purchase intention of peripheric products, where about 48% of respondents chose neutral or negative opinions (score 1, 2, or 3).

Table 1.

The results of all consumers’ answers.

In consumer respondents’ interviews, most chose 4 for CSR items’ importance and 5 for team identification related to CSR efforts. The reason is as follows: “we know our team is not profitable. We did not give 5 for CSR’s importance because we did not think our favorite team had many resources to engage in it. However, if some CSR activities were done, they would enhance team identification”. Our interview with expert practitioners in CBA confirmed the lack of motivation for purchasing peripherical products: “in this era of high-speed media and logistics, the fans can easily buy the peripherical product of top clubs in the world, that is, NBA teams. We find it hard to develop peripherical products for only a few hardcore fans motivated to buy them.” This message revealed that most CBA fans were also NBA fans simultaneously. The CBA teams’ peripherical products could, at most, only be the second-best choice for them to show their identity in daily life.

For our H1 and H2, the respondents gave a direct validation in their answers. They expressed their positive responses to the hypothetical CSR efforts. For H1 and H2’s sub-hypotheses, H3 and H4, we used relational data analysis to assess them in the following subsection.

4.2. Relational Data Analysis

4.2.1. Reliability and Validity of Questionnaire for Factorial Analysis

Reliability tests were performed for each theoretical construct of our questionnaire with Cronbach’s alpha values. The results are shown in Table 2. All constructs are far above the threshold value of 0.70 suggested by Hair JR, Black, Babin, and Anderson [97]. This means that, considering the variation level of the collected responses, our sample size of 373 is large enough and obtains a consistent outcome for reproducible analysis results [98].

Table 2.

The reliability of each theoretical construct of the questionnaire.

For the structural validity of this questionnaire, the Bartlett test’s significance is smaller than 0.001, while the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin score is 0.94, which is well acceptable according to the suggestion of Hair JR, Black, Babin, and Anderson [97]. These results mean that the size of 373 of our sample is sufficient, and our questionnaire is suitable for factorial analysis.

4.2.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Without a predefined number of factors, the SPSS factorized our questionnaire into six constructs (Table 3). However, the classification of our questionnaire’s items is quite different from the theoretical construct structure of CSR, team identification, and clubs’ sustainable development according to the design of our questionnaire.

Table 3.

Exploratory Factor Analysis of all items in the questionnaire.

Contrary to other factorial analyses in the same field [64] with perfect correspondence between factorial classification and constructs’ structure in the questionnaire design, the CSR items in our study were not classified just as Carroll’s four-stage system [32], while the team identification and clubs’ sustainable development were not separated apart from each other.

For the items in our questionnaire, team identification and the clubs’ sustainable development are classified as the same factor (Factor 1). However, under a one-way ANOVA post-hoc test, comparing items of team identification (TI 1~TI 7) and the items of purchase intentions (CSD 1~CSD 3), there were always significant differences between these items (p < 0.01). Ethical and philanthropic responsibility items were heavily loaded into the same factor (Factor 2). In our interview with consumer respondents, we were told they had difficulty explaining the differences between ethical and philanthropic responsibilities. Cultural differences may cause this, e.g., in China, schooling activities and community security are entirely taken charge of by the state. The CBA clubs’ participation in these activities is generally considered as taking ethical responsibilities rather than philanthropic responsibilities.

4.2.3. Correlations between These Theoretical Constructs

With the mean and standard deviation of items’ answers within each theoretical construct, we obtained the correlation between different constructs as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mean and standard deviation of answers within each theoretical construct and the correlations (r value) between different constructs.

We found that answers were concentrated around 4 for all constructs. Standard deviations were always less than 0.5. For each construct of CSR, the correlation existed only between the neighboring stages, that is, , , and . Only the correlation between TI and the CSD is strong ().

The weak relationship between the different constructs of CSR and CSD made it impossible to verify a moderating role of TI between them (H4-1/-2/-3/-4). In fact, if we make the product of CSR constructs (ER, LR, EtR, and PR) and TI as new factors, the correlations between these new factors and CSD is just between 0.72 and 0.74 (, , , and ), lower than the direct correlation between TI and CS ().

If we take all CSR items as one single factor, the results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mean and standard deviation of answers in CSR awareness, team identification, clubs’ sustainable development, and the correlations (r value) between them.

These results showed that the respondents held high expectations for CBA clubs’ CSR efforts and expressed their pride and intention to reward their favorite clubs’ kindness (Table 3). The correlation remained weak between CSR expectations, the increase in pride, and purchasing intentions related to CSR efforts (Table 4 and Table 5). Therefore, we validated H3 of this study, which linked the team identification and the clubs’ sustainable development with a coefficient of correlation higher than 0.8. Nevertheless, the sub-hypothesis of H1-1/-2/-3/-4 and H2-1/-2/-3/-4 could not be validated in our study, for the correlation coefficients are generally lower than 0.4. This weak relationship between CSR and CSD makes it impossible to verify the moderating effect of TI (H4). In fact, , lower than the direct correlation between TI and CSD ().

4.3. Structural Equation Model

To quantify the fitness of our research model, the SEM’s confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indices are calculated with the maximum likelihood method and are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

The research model’s fitting index.

According to the suggested values given by the work of Jung [64], and according to the handbook of Hair JR, Black, Babin, and Anderson [97], we found that the research model did not fit well with the results of our survey. Just as with the EFA step of our study, the inner structure of our collected sample data is different from our theoretical research model.

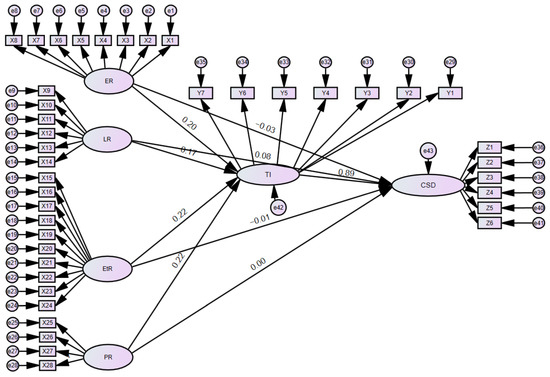

With structural path estimates, we can obtain the standard estimates of the principal paths as in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

AMOS SPSS output of the path diagram for the structural model, where ER: economic responsibility; LR: legal responsibility; EtR: ethnical responsibility; PR: philanthropic responsibility; TI: team identification; CSD: clubs’ sustainable development; X1~28: CSR items; Y1~Y7: team identification items; and Z1~Z6: clubs’ sustainable development items. e1~43: residual error of each item. H1-1~H3: the hypothetical links.

Like the correlation between different constructs, only the regression weight between TI and the CSD is greater than 0.8. Other regression weights of the principal paths are near zero.

To understand the weak relationship between the evaluation of CSR’s importance and the TI and the CSD, we interviewed some consumer respondents about their general attitude toward their favorite clubs’ CSR involvement. We found that passionate fans were aware of the financial situation of their favorite CBA club. Most selected 4 instead of 5 in the CSR items because they considered their favorite clubs’ limited financial resources. However, if the club had engaged in more CSR, they would have been proud and deepened their identification with the club. For the items concerning the clubs’ sustainable development, their weak correlation with the CSR factors means that those who had attached the highest importance to CSR factors did not increase that much in their purchase intention and team loyalty. Expert CBA practitioners felt the same way about CSR involvement as ardent fans. On the one hand, they agree with the social values contained therein; on the other hand, they do not want the CSR activities to become a burden more significant than their club could bear.

4.4. Findings

For our H1 and H2, the respondents have already given a direct validation in their answers. They have generally expressed their positive reaction to the hypothetical CSR efforts. In our H3, the correlation between the TI and the CSD are validated with . However, the items in our questionnaire could not stand structural modelling analysis according to Carroll’s model (1991), probably because of the cultural and institutional differences between China and the US. The correlation between CSR awareness with TI (, regression weights < 0.3 and CSD , regression weights < 0.1) is weak, which means those who unreservedly highlight the importance of CSR efforts are not necessarily those who intend most to increase their support for the club as a reward to their favorite teams’ CSR efforts.

Following prudential principles, our research began with the framework and questionnaires of validated studies [64,73] in the developed market environment, but ended up with challenging its applicability to the CPSO market for relational data analysis. The questionnaire turns out to be in need of further adaptation due to the market and regime differences, e.g., the widely used indicator, Tobin’s q, has been found to be without a significant relationship with corporate performance in a study of Iranian manufacturing companies [99]. The lack of structural validity of the theoretical constructs and the weak correlation between CSR and CSD prevent us from conducting in-depth analyses of the relationships between these theoretical constructs, e.g., as an investigation of moderating the role of internal control between earnings management, related party transactions, and corporate performance [99].

5. Conclusions

The objective of this study is to assess the impact of CPSO’s CSR efforts on their sustainable business development. The analysis includes descriptive statistical methods of direct responses of fans’ awareness and relational analysis methods to evaluate CSR’s enhancement effects on different factors, i.e., TI and CSD, and plans to verify if TI has a moderating effect between CSR and CSD.

To conclude, there are three major academic discoveries in this study: (i) under the existing framework validated in PSOs in mature markets, our study has the results of the descriptive statistics supporting our H1 and H2 concerning CSR efforts’ positive effects on TI and CSD. (ii) The lack of structural validity in our sample data calls for new research frameworks and adjusted questionnaires in future studies to be more adapted to the new sports market in China. (iii) The relationship between consumers’ evaluations of CSR’s importance and TI or/and their favorite club’s sustainable development is weak, thus relational analysis did not support our H1, H2, and H4. However, the true considerations of fans are more complex than a weak correlation. In other words, fans generally consider their favorite CBA teams’ CSR efforts important, but the importance attached to CSR is not proportional to their CSR-related TI and CSD. For practical implications, this study suggests that the CPSOs assume social responsibilities but not beyond what they can afford to do.

According to the descriptive statistics of our sample data, CSR items are generally highly considered and well expected by CBA consumers. In their answers, the consumers claimed that they would generally increase their TI, purchase intention, and team loyalty as a reward for clubs’ CSR initiatives.

However, more details than descriptive statistics results are revealed with more sophisticated quantitative methods. In EFA, our respondents’ answers to the items of the four constructs of CSR, TI, and CSD did not confirm the structural validity as in similar studies launched in developed markets, e.g., the “four major leagues” in North America [64]. This lack of structural validity challenged the existing research frameworks’ applicability to research in new developing markets with different social systems. This calls for new conceptions of the research framework and questionnaire in the new Chinese sports market, with more adapted evaluable questions/items to better reflect the invisible factors of CSR (ER, LR, EtR, and PR) and the other factors related to the CSD, e.g., TI, team loyalty, purchase intention, etc.

For correlation analysis, only the relationship between team identification and the clubs’ sustainable development could be observed. Through the CFA of our SEM study, we obtained a similar result that the items/factors have weak structural validity, contrary to their structure in studies in developed markets. The weak correlation between consumers’ evaluation of CSR’s importance and team identification or/and their favorite clubs’ sustainable development reveals that the passionate fans encourage CSR efforts with some reserves, for they are aware of their favorite clubs’ financial difficulties and do not want CSR involvements to become a burden more significant than their favorite clubs can bear.

Our study suggests that the Chinese PSOs may manage their CSR activities and disclosure from another point of view, e.g., the balance between the satisfaction of fans’ expectations and the spending of resources. Similar to how focal corporates in supply networks integrate strong and weak ties for additional innovation outcomes [100], this study may, in general, encourage the CBA clubs to assume social responsibilities and integrate CSR disclosure into the teams’ strategic plan to meet the stakeholders’ expectations and increase their brand value. However, the sound effects may not increase linearly with CSR involvement, and the clubs only need to engage within their financial limits.

6. Limitations

Firstly, to our best knowledge, there are no authoritative detailed statistics on the demographic composition of CBA fans. Therefore, we cannot demonstrate the representativeness of our sampling in this research. However, the activeness of the respondents in the fans’ online community and their young age, with higher education and income, made them represent the most valuable consumer group. Secondly, this is a questionnaire-based study for respondents’ opinions about hypothetical scenarios of CSR engagement and related purchase intentions, which are not converted to purchase actions. Thirdly, according to what we have conceived in our questionnaire, the theoretical framework cannot obtain similar structural validity in China as in developed countries because of cultural and institutional differences and PSOs’ different financial situations [101]. Finally, due to a lack of historical information about CSR in China and with a single sample in our study, we can only question the applicability of existing research frameworks. Future CSR studies in the Chinese professional sports market may need a new framework and a newly designed questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; Data curation, J.L.; Formal analysis, R.Y.M.L. and W.L.; Investigation, J.L.; Methodology, J.D.; Project administration, J.D.; Resources, J.L.; Supervision, J.D. and R.Y.M.L.; Validation, J.D.; Visualization, W.L.; Writing—original draft, J.L.; Writing—review & editing, R.Y.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University (R. 270/2022, approved on 20 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1VrF2gdEUxH3LnLxhiEH_6rmgeWmEy0Yp/edit?usp=sharing&ouid=102470968287360677102&rtpof=true&sd=true.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire on CBA fans’ opinion about their favorite teams’ CSR involvement, CSR-concerned team identification, and clubs’ sustainable development.

Table A1.

Questionnaire on CBA fans’ opinion about their favorite teams’ CSR involvement, CSR-concerned team identification, and clubs’ sustainable development.

| Demographic Information |

|

| Opinions about CSR Efforts |

|

| CSR-Related Team Identification |

In response to my favourite team’s CSR efforts:

|

| CSR-Related Club’s Sustainable Development |

In response to my favourite team’s CSR efforts:

|

References

- Jang, E.W.; Wu, L.; Wen, T.J. Understanding the effects of different types of meaningful sports consumption on sports consumers’ emotions, motivations, and behavioral intentions. Sport Manag. Rev. 2021, 24, 46–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Shonk, J.D.; Bang, H. Professional team sports organizations’ corporate social responsibility activities: Corporate image and chosen communication outlets’ influence on consumers’ reactions. Int. J. Sport Commun. 2021, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasios-Panagiotis, K. Branding and CSR in Sports Organizations. Master’s Thesis, University Center of International Programmes of Studies School of Science and Technology, Thessaloniki, Greece, 2022; 52p. [Google Scholar]

- Bradish, C.; Cronin, J.J. Corporate social responsibility in sport. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 691–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.B.; Chen, M.-H.; Tai, P.-N.; Hsiung, W.-C. Constructing the corporate social responsibility indicators of professional sport organization. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2015, 6, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walker, M.; Kent, A. Do fans care? Assessing the influence of corporate social responsibility on consumer attitudes in the sport industry. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 743–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, T.; Duffett, R.; Knott, B. Environmental factors and stakeholders influence on professional sport organizations engagement in sustainable corporate social responsibility: A South African perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero, Q.J.; Rivera-Camino, J. CSR serves to compete in the sport industry? An exploratory research in the football sector in Peru. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2016, 13, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, G. Measuring corporate sustainability. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2010, 43, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappato, A.; Pennazio, V. Corporate Social Responsibility in Sport—Torino 2006 Olymic Winter Games; University of Studies of Turin: Torino, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Filizöza, B.; Fiúneb, M. Corporate social responsibility: A study of striking corporate social responsibility practices in sport management. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1405–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M.T.; Greyser, S. Revealing the Corporation: Perspectives on Identity, Image, Reputation, Corporate Branding, and Corporate-Level Marketing: An Anthology; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenkorf, N. Managing sport for development: Reflections and outlook. Sport Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, M.-C. Sustainable entrepreneurship in the Romanian sports industry. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2019, 13, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, S.; Hamil, S. corporate social responsibility in the Scottish Premier League: Premier League: Context and motivation. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2011, 11, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, H.E.; Yeh, C.-C.; Wang, L.-H.; Fung, H.-G. The relationship between CSR and performance: Evidence in China. Pac. Basin Finance J. 2018, 51, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.K.; Byon, K.K.; Song, H.; Kim, K. Internal contributions to initiating corporate social responsibility in sport organizations. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 1804–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRC State Council- Sport. Opinions of the State Council on Accelerating the Development of Sports Industry and Promoting Sports Consumption; PRC State Council: Beijing, China, 2014.

- PRC State Council. Overall Plan for Decoupling of Trade Associations and Chambers of Commerce from Administrative Organs; PRC State Council: Beijing, China, 2015; Volume 21.

- Deloitte. CBA League Performance White Paper; Deloitte: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X. Development of the sports industry: New opportunities and challenges. China Sport Sci. 2020, 39, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Tan, J. Research on theoretical system of social responsibility of professional sports organizations. J. Cap. Inst. Phys. Educ. 2013, 25, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Rong, S. Social responsibility of professional sports organizations: Concept, characteristics and content. Shandong Inst. Phys. Educ. 2018, 34, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Y. The development logic of Chinese professional sports organizations. J. Shenyang Inst. Phys. Educ. 2019, 38, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Barbu, R.C.M.; Popescu, C.M.; Burcea, B.G.; Costin, D.-E.; Popa, G.M.; Păsărin, L.-D.; Turcu, I. Sustainability and social responsibility of Romanian sport organizations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. Reform path of CBA League system under the background of substantiation of Chinese Basketball Association. J. Shenyang Sport Univ. 2018, 37, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, B.A. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; University of Iowa Press: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, B.A. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A.; Shabana, M.K. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.; Stirling-Schrempf, J.; Stutz, C. The past, history, and corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 166, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, F. Corporate social responsibility: To what extent businesses should contribute from theoretical perspective? Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.M.; Carroll, B.A. Corporate social responsibility: A three-domain approach. Bus. Ethics Q. 2003, 13, 503–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Reber, H.B. Dimensions of disclosures: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reporting by media companies. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husted, W.B.; Allen, B.D. Strategic corporate social responsibility and value creation among large firms: Lessons from the Spanish experience. Long Range Plan. 2007, 40, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, E.M.; Kramer, R.M. Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, M.C.S.; Sardinha, D.M.I.; Reijnders, L. The effect of corporate social responsibility on consumer satisfaction and perceived value: The case of the automobile industry sector in Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 37, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlou, I.; Stergioulas, A.; Tripolitsionti, A. Environmental responsibility in the sport industry: Why it makes sense. Sport Manag. Int. J. 2006, 2, 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Roeck, D.K.; Delobbe, N. Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, A.; Gruning, M. The impact of corporate identity on corporate social responsibility disclosure. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2018, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wickert, C.; Scherer, G.A.; Spence, J.L. Walking and talking corporate social responsibility: Implications of firm size and organizational cost. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1169–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.A. Corporate social responsibility: The centerpiece of competing and complementary. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, S.D.; Wright, M.P. Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristache, A.D.; Paicu, E.C.; Ismail, N. Corporate social responsibility and organizational identity in post-crisis economy. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2013, 20, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Otubanjo, O. Theorising the Interconnectivity between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Corporate Identity. J. Manag. Sustain. 2012, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M.T. Corporate identity, corporate branding and corporate marketing—Seeing through the fog. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 248–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, C.; Shilbury, D. Integrating corporate social responsibility in English football: Towards multi-theoretical integration. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 3, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, H.; Babiak, K. Beyond the game: Perceptions and practices of corporate social responsibility in the professional sport industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, K.; Wolfe, R. Determinants of corporate social responsibility in professional sport: Internal and external factors. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 717–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, R.; Lachowetz, T.; Clark, J. Cause-related sport marketing: Can this marketing strategy affect company decision-makers? J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Parent, M.M. Toward an integrated framework of corporate social responsibility, responsiveness, and citizenship in sport. Sport Manag. Rev. 2010, 13, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, G.; Nguyen, N. Cues used by customers evaluating corporate image in service firms: An empirical study in financial institiutions. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2013, 7, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvoittu, A. The Effects of Greenwashing on Consumer Behaviour. Bachelor’s Thesis, Haaga-Helia University of Applied Sciences, Helsinki, Finland, 2022; 34p. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.J.; Hull, K. Examining public perceptions of CSR in sport. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2018, 23, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, S.; Walker, M.; Barry, E.A. Sport as a vehicle for health promotion: A shared value example of corporate social responsibility. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Inoue, Y.; Filo, K.; Sato, M. Creating shared value and sport employees’ job performance: The mediating effect of work engagement. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2022, 22, 272–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, C.P. Corporate social responsibility in sport: An overview and key issues. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. CSR in Sport: Investigating environmental sustainability in UK Premier League Football Clubs. Polit. Sci. 2011, 24, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. Research on Social Responsibility of CBA Clubs in China. Master’s Thesis, Chengdu Institute of Physical Education, Chengdu, China, 2019; 81p. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, W.C. The Influence of Professional Sports Team’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on Team Image, Team Identification, and Team Loyalty. Ph.D. Thesis, St. Thomas University, Miami Gardens, FL, USA, 2012; 117p. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, H. Analysis of the growth and development of basketball game in context of China: A case of Chinese Basketball association. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2021, 29, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kihl, A.L.; Tainsky, S.; Babiak, K.; Bang, H. Evaluation of a cross-sector community initiative partnership: Delivering a local sport program. Eval. Program Plan. 2014, 44, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şirin, E.Y.; Döşyılmaz, E. Corporate social responsibility perceptions of Turkish football fans: TFF 1st Lig and 2nd Lig examples. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2019, 7, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. UN Global Compact-Accenture: A New Era of Sustainability; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cobourn, S.; Frawley, S. CSR in professional sport: An examination of community models. Manag. Sport Leis. 2017, 22, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, D. Corporate Social Responsibility in Sport: Efforts and Communication. Ph.D. Thesis, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2017; 426p. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, Y. Research on the content of corporate social responsibility of professional sports clubs in China under the five-in-one background. Anhui Sports Technol. 2019, 40, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Report on The Development of Sports Industry of CHINA; Blue Book of Sports: Irvine, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.J.; Ross, S. Comparing sport consumer motivations across multiple sports. Sport Mark. Q. 2004, 13, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Balmer, J.M.T. A grounded theory of the corporate identity and corporate strategy dynamic. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 401–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M.; Torres, E. The influence of corporate image on consumer trust: A comparative analysis in traditional versus internet banking. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.R.; Hunt, D.S. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdeshmukh, D.; Singh, J.; Sabol, B. Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branscombe, R.N.; Wann, L.D. The positive social and self concept consequences of sports team identification. J. Sport Soc. Issues 1991, 15, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal, R.; Chen, J. Moderating and mediating effects of team identification in regard to causal attributions and summary judgments following a game outcome. J. Sport Manag. 2008, 22, 717–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.R.; Wakefield, L.K. Factors leading to group identification: A field study of winners and losers. Psychol. Mark. 1998, 15, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, H.P. Managing brand equity. Mark. Res. 1989, 1, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiotsou, R. Developing a scale for measuring the personality of sport teams. J. Serv. Mark. 2012, 26, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, L.K.N.; Voges, K. The impact of sport sponsorship activities. corporate image. and prior use on consumer purchase intention. Sport Mark. Q. 2000, 9, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Stokburger-Sauer, E.N.; Bauer, H.H.; Exler, S. Brand image and fan loyalty in professional team sport: A refined model and empirical assessment. J. Sport Manag. 2008, 22, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Wu, Y.; Mehmood, K.; Jabeen, F.; Iftikhar, Y.; Acevedo-Duque, A.; Kwan, K.H. Impact of spectators’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility on regional attachment in sports: Three-wave indirect effects of spectators’ pride and team identification. Sustainability 2021, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Manoli, A.E. Building team brand equity through perceived CSR: The mediating role of dual identification. J. Strateg. Mark. 2020, 30, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.-C.; Kaplanidou, K. Service quality, perceived value and behavioral intentions among highly and lowly identified baseball consumers across nations. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2021, 21, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K. The effects of team identification on consumer purchase intention in sports influencer marketing: The mediation effect of ad content value moderated by sports influencer credibility. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1957073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, J. Effect of corporate image of the sponsor on brand love and purchase intentions: The moderating role of sports involvement. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2020, 30, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, F.K.; Sajjad, A.; Bashir, R.; Shaukat, B.M.; Khan, B.M.; Sahibzada, F.U. Revisiting the relationship between corporate social responsibility and organizational performance: The mediating role of team outcomes. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1630–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, H.; Rezaei, Z.; Rozfarakh, A.; Abdollahi, H.M. The relationship between team social responsibility and patronage intentions football premier league fans: The moderator role of team identity. Sport Psychol. Stud. 2022, 10, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, B.; Yeung, M. Chinese consumers’ perception of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 88, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Handbook of Management Research Scales; Renmin University of China Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, E.B. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y.; Havitz, E.M. Examining relationships between leisure involvement, psychological commitment and loyalty to a recreation agency. J. Leis. Res. 2004, 36, 104–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, C.W.; Babin, J.B.; Anderson, E.R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimon, G.; Appolloni, A.; Tarighi, H.; Shahmohammadi, S.; Daneshpou, E. Earnings management, related party transactions and corporate performance: The moderating role of internal control. Risks 2021, 9, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemargi, N.; Tavoletti, E.; Appolloni, A.; Cerruti, C. Managing open innovation within supply networks in mature industries. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, A.A.; Shaikh, A.R.; Appolloni, A. Blow the whistle or dance to a tune! An ethical dilemma. Emerald Emerg. Mark. Case Stud. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).