Special Sacrifice and Determination of Compensation Standard for Land Expropriation in the Urbanization Process—A Perspective of Legal Practice

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Materials

2.2. Research Methods

3. Empirical Research Results

3.1. Sources of Data

3.2. The Empirical Model and Variable Setting

3.2.1. The Empirical Model Setting

3.2.2. The Variable Setting

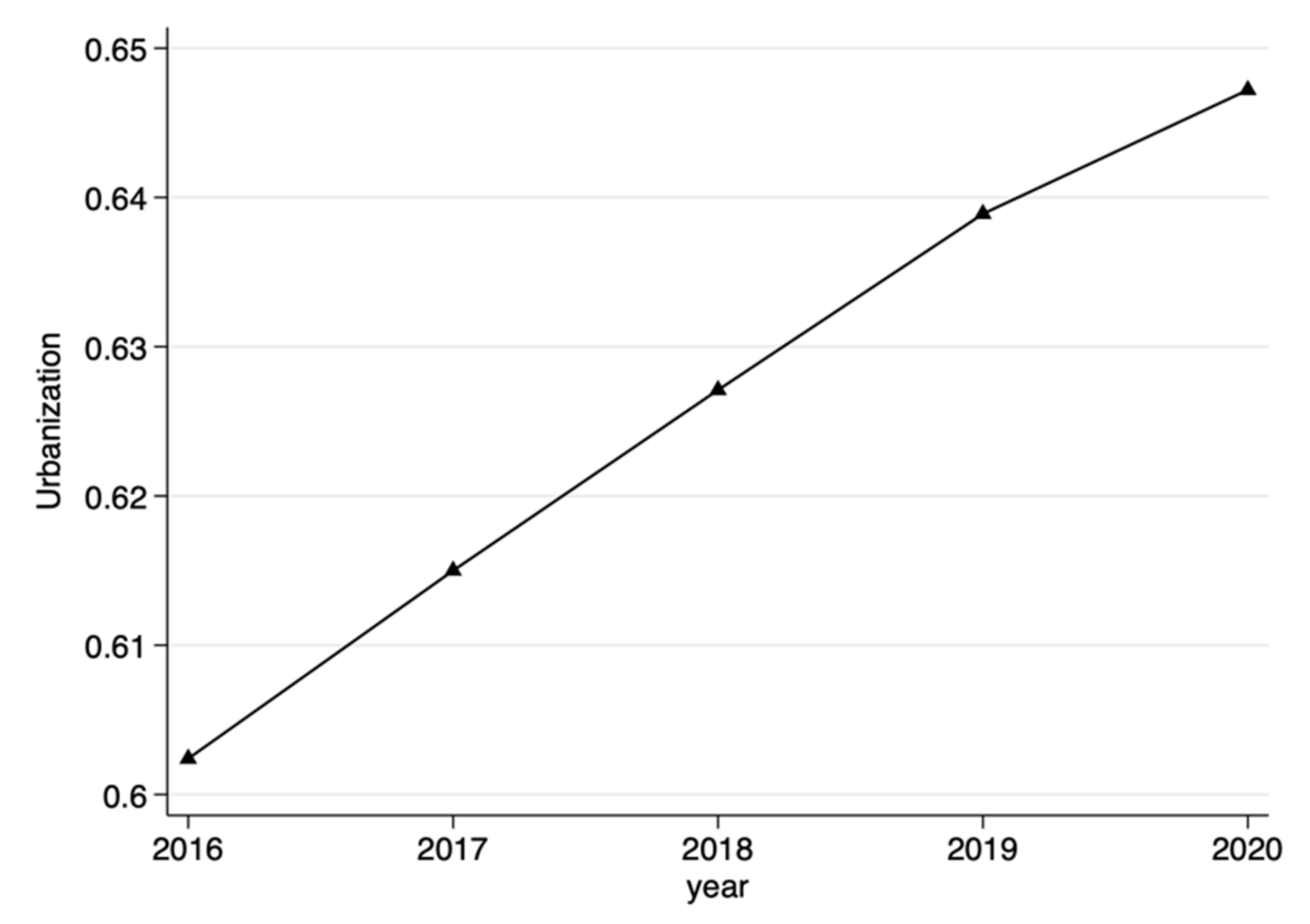

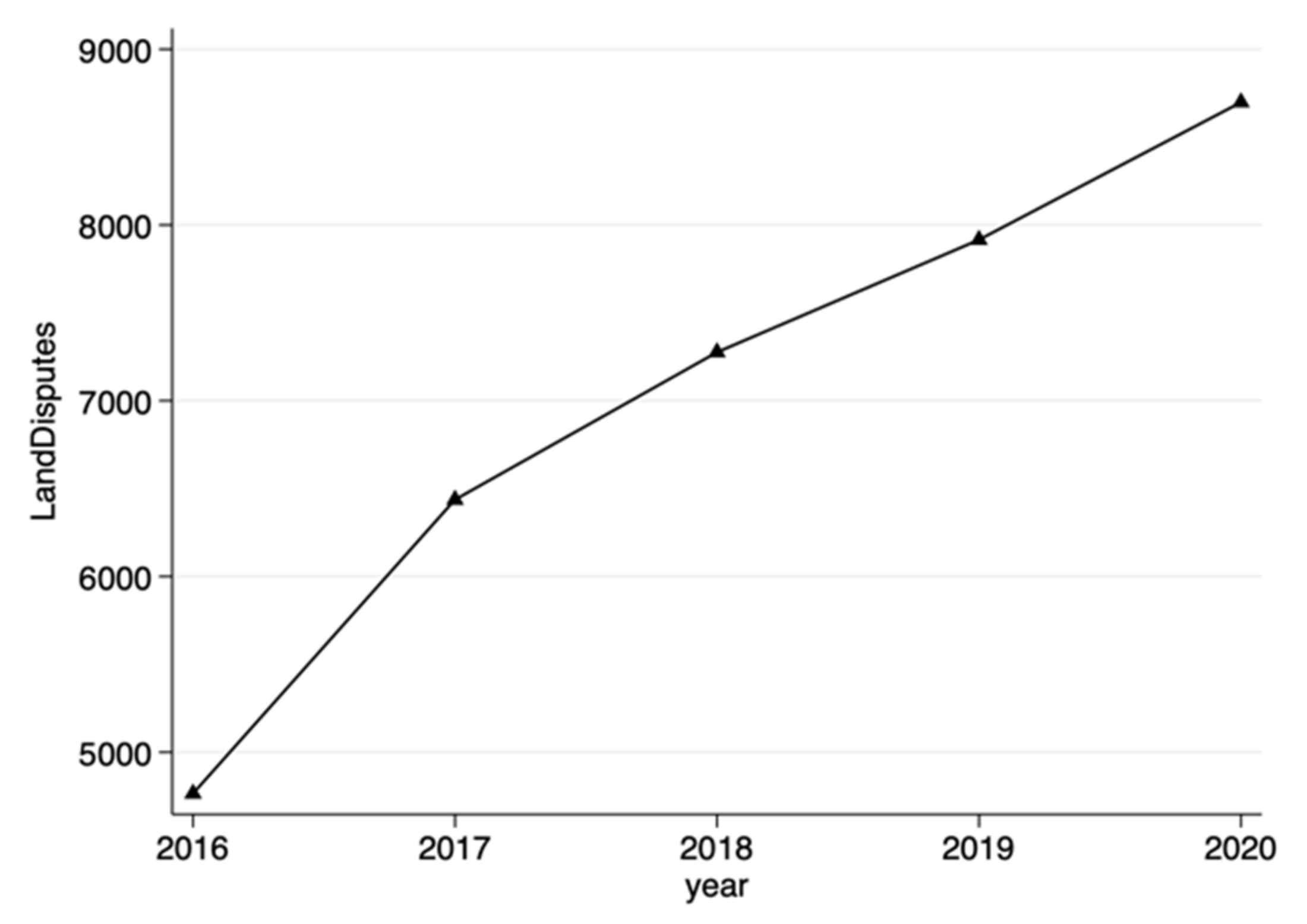

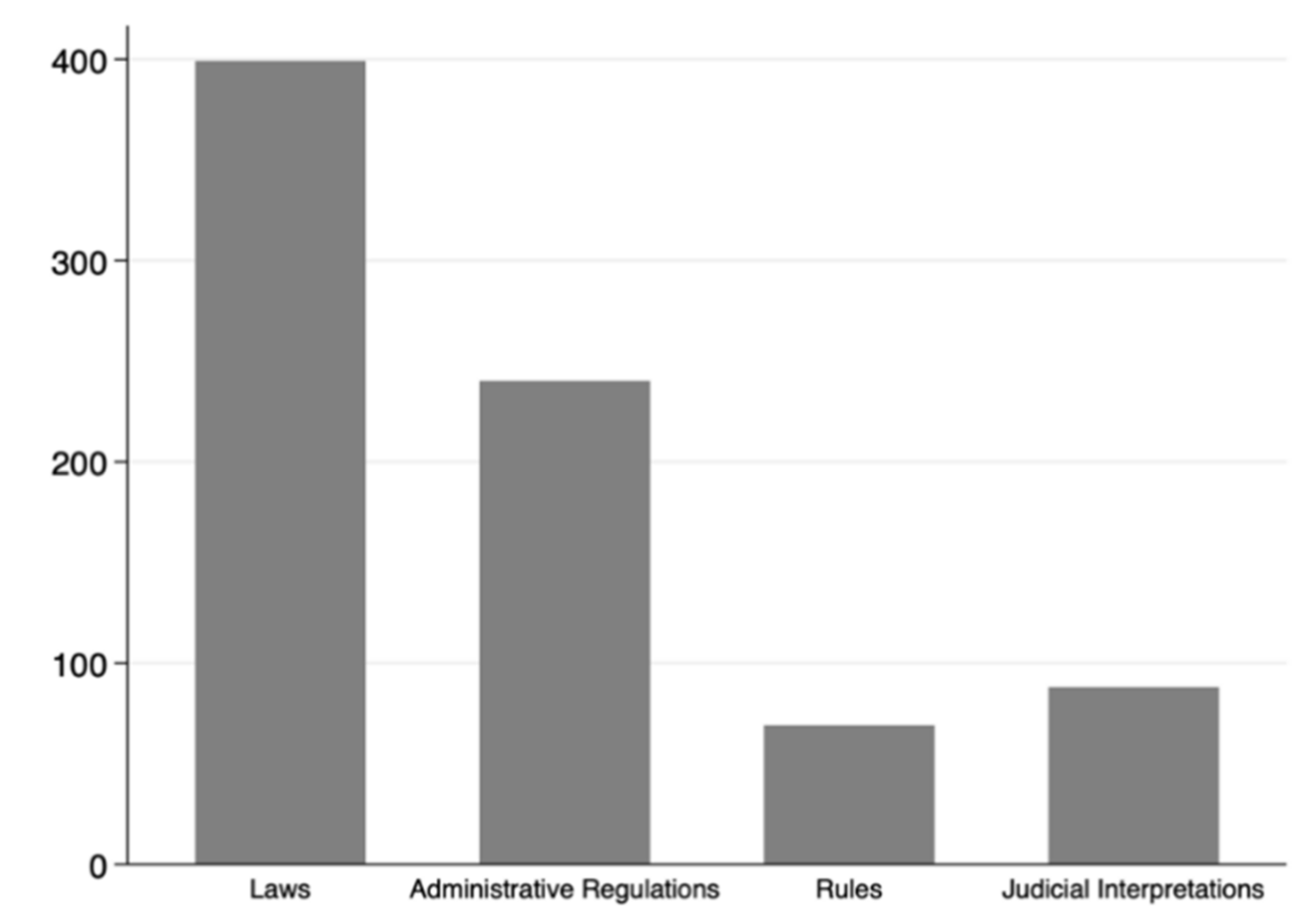

3.3. Characteristic Facts

3.4. Results of the Empirical Research

3.5. Robustness Test of the Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Identification and Recognition of Compensation for Land Expropriation

4.1.1. Legalization of Compensation for Land Expropriation

4.1.2. Compensation Determination Standards for Land Expropriation

4.2. Diversity and Selection of Compensation Standards for Land Expropriation

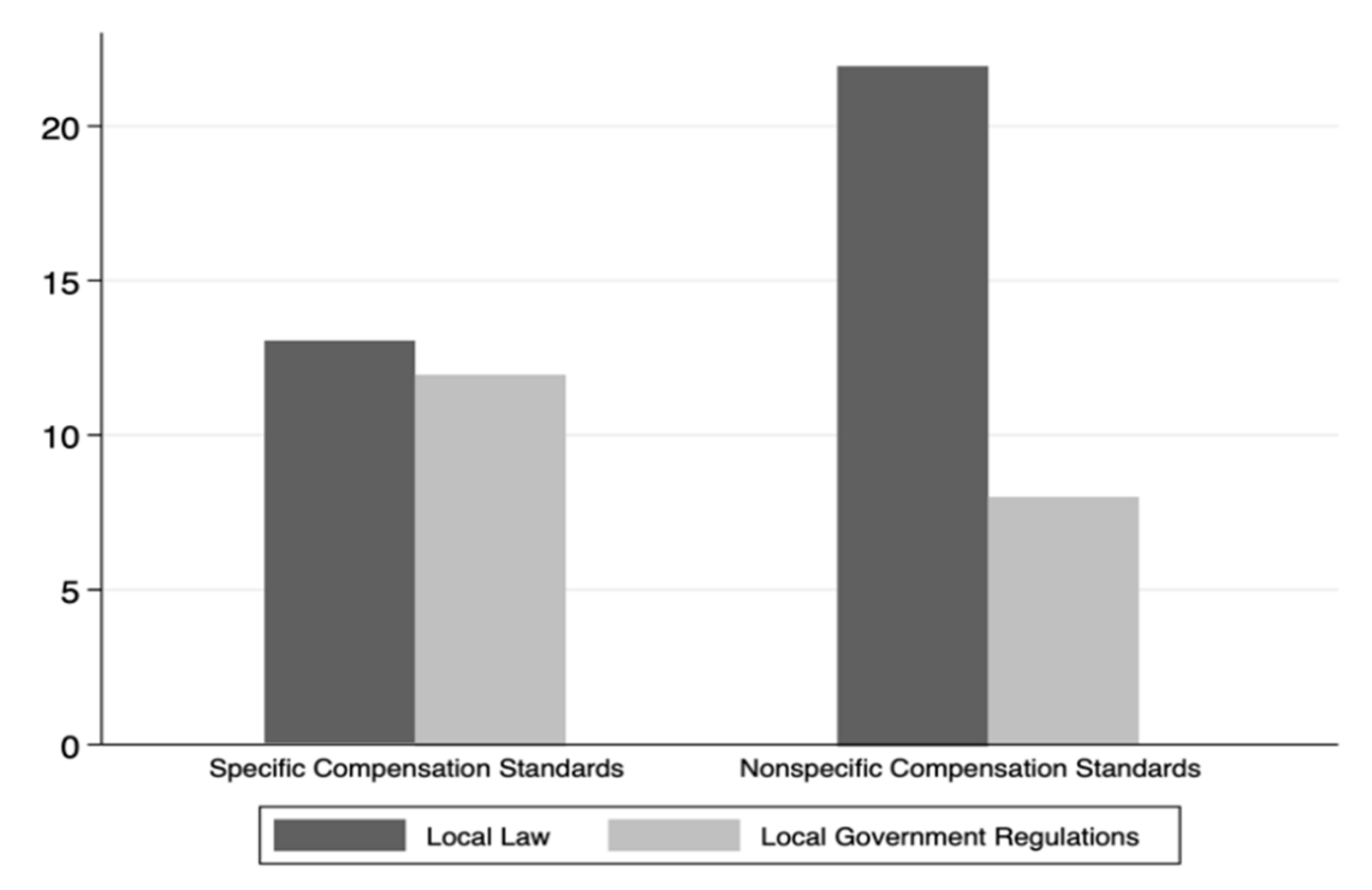

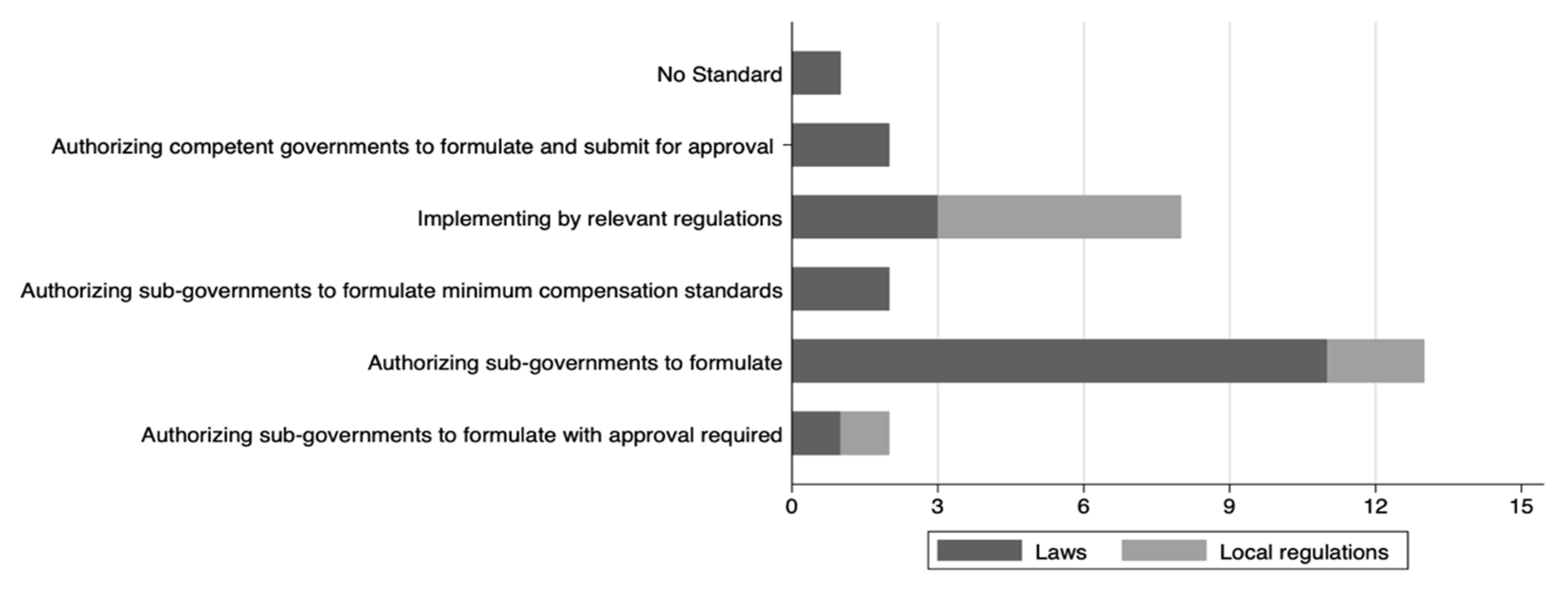

4.2.1. Compensation Standards for Land Expropriation in Legislative Texts

4.2.2. Compensation Standards for Land Expropriation in Judicial Practice

4.2.3. Establishing Fair Compensation Standards for Land Expropriation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Z.; Peng, W.Z.J. Empirical Analysis of Land Expropriation Compensation Negotiation and Farmers’ Rights Protection. Econ. Geogr. 2019, 4, 182–191. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y. Procedural Justice Precedes Monetary Compensation: Determining Farmers’ Satisfaction with Land Expropriation. Manag. World 2012, 2, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Soliman, A.M. The Right to Land: To Whom Belongs after a Reconciliation Law in Egypt. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 2022, 6, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.N.; Bai, Z.K. The United States, Britain, and Germany’s Land Expropriation Compensation System and Experience to Draw on. China Land 2014, 4, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Treeger, C. Legal Analysis of Farmland Expropriation in Namibia. In Constitution; Konrad Adenauer Foundation: Bonn, Germany, 2004; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S. Determination of the Ownership of Marketed Land For-profit and its Coordination with Land Expropriation System in the Process of Urbanization. Contemp. Law Rev. 2016, 6, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. The Future Trend of Land System Reform in Urbanization: A Review of China’s Research Achievements in the Past 10 Years. J. Gansu Univ. Admin. 2013, 4, 102–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.G. Conversations and Controversies between Economists and Jurists on China’s Land System. J. Gansu Univ. Admin. 2010, 2, 98–116. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.Y. Research on the Compensation System for Land Expropriation. Chin. Legal Sci. 2005, 3, 135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, G.L.; Wang, J.X. Research on the Compensation System for Land Expropriation. Trib. Polit. Sci. Law 2005, 2, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. Construction of China’s Collective Land Expropriation System. Chin. J. Law 2016, 1, 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Tan, S.K.; Zhang, A.L. Research on the Differences in Compensation for Land Expropriation for Public Welfare and Non-public Welfare: Based on Questionnaires of 543 Farmers and 83 Cases of Expropriation in 54 Villages in 4 Cities of Hubei Province. Manag. World 2009, 10, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Peng, J. Reasonable Determination of Land Expropriation Compensation Fees. China Land Sci. 2006, 1, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.H. The Normative Changes and Functional Shifts of China’s Land Expropriation Compensation Clauses. Nanjing Soc. Sci. 2021, 11, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, M.H.; Zhou, Z.F. Research on Compensation Standards for Land Expropriation in China: Based on Analysis of Local Legislative Texts. Chin. J. Law 2009, 3, 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Wu, J.; Xi, Z.; Zhang, W. Farmers’ Satisfaction with Land Expropriation System Reform: A Case Study in China. Land 2021, 10, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.X.; Bu, T.T.; Wu, Z.T. Research on Compensation Standards for Land Expropriation Based on Comprehensive Value of Cultivated Land. China Popul.·Resour. Environ. 2011, 9, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Dires, T.; Fentie, D.; Hunie, Y.; Nega, W.; Tenaw, M.; Agegnehu, S.K.; Mansberger, R. Assessing the Impacts of Expropriation and Compensation on Livelihood of Farmers: The Case of Peri-Urban Debre Markos, Ethiopia. Land 2021, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.B. The Judicial Protection Mechanism of American Property Rights and Its Enlightenment to China: From the Perspective of Expropriation; Shanghai SDX Joint Publishing Company: Shanghai, China, 2017; p. 78. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.M. The Constitutional Property Rights Guarantee System and the Concept of Public Interest Expropriation. Natl. Chengchi Law Rev. 1986, 33, 193–232. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.S. Discussion on the Compensation System for Public Expropriation in Japan’s Law. Natl. Chung Cheng Univ. Law J. 1998, 1, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, B.C.; Zhan, Z.L. The Law of State Responsibility: Also on Administrative Compensation and Administrative Reparation in Mainland China; Angle Publishing Company: Taipei, China, 2005; pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.Q. The Special Sacrifice of Property Rights and Social Obligations: Commentary on the Interpretation of Int. 747 of the Judicial Yuan Justice. Court Case Times 2017, 64, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, H. General Introduction to Administrative Law; Gao, J., Translator; Law Press: Beijing, China, 2000; p. 667. [Google Scholar]

- Ugo, M. Basic Principles of Property Law: A Comparative Legal and Economic Introduction; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 2000; p. 195. [Google Scholar]

- Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 U.S.393. 1922. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/260/393/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Penn Central Transp. Co. v. New York City, 438 U.S.40. 1960. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/438/104/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Lucas, V. South Carolina Coastal Council, 505 U.S.1003. 1992. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/505/1003/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- The Court identified two types of takings: One in which the government took physical control, and another in which the government regulations removed all economic and beneficial use of the property. See Daniel Shudlick, Objects as Obligation in Property. Ariz. Law Rev. 2018, 60, 1020.

- Ye, B.X. The Significance of Compensation for Administrative Losses, New Theory of Contemporary Public Law: Proceedings of Professor Weng Yuesheng’s Seventieth Birthday; Angle Publishing Company: Taipei, China, 2002; p. 292. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.Y. The Connotation and Interpretive Structure of Property Rights Protection. Cheng Kung Law Rev. 2006, 11, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.H. Subsidiary Expropriation of Urban Planning: Analysis of Supreme Administrative Court Judgment No. 01442. Taiwan Law J. 2012, 201, 231. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.S. The Statutory Principles of Compensation for Administrative Losses: No Law No Compensation? Taiwan Local Law J. 2005, 71, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.Q. On the Management Obligation and Compensation Liability for the Leveling of Private Arcades. Chung Hsing Univ. Law 2017, 21, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Z.Z. A Preliminary Discussion on the Principle of Proportionality in Public Law: Focusing on the Development of German Law. Natl. Chengchi Univ. Law Rev. 1999, 62, 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.F. Land Use Restriction Forms Special Sacrificial Loss Compensation Claims: The Meaning of Int. 747 of the Judicial Yuan Justice. Court Case Times 2017, 64, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.L. Research on Several Issues Concerning the Land Expropriation and Compensation Law. Natl. Taiwan Univ. Law Study Ser. 1991, 1, 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.Y. Research on the State’s Liability for Compensation. Tunghai Univ. Law Rev. 2000, 15, 114–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.C. Standards for Expropriation Compensation in Article 30 of the Land Expropriation Regulations: A Comprehensive Review of the Supreme Administrative Court’s Judgments After 2000. Acad. Sin. Law J. 2010, 6, 167–206. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.C. Land Normative Standards and Empirical Evaluation of Expropriation and Compensation. Soochow Law J. 2011, 2011, 27–64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N. Land Expropriation System of the United States. China Land 2001, 4, 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L. The Canadian Land Expropriation System and Its Lessons. China Land 2000, 8, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. A Comparative Study of Land Expropriation Systems. J. Comp. Law 2004, 6, 16–30. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Name | Variable Symbol | Observation | Average | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Expropriation Disputes | Land Disputes | 1430 | 2.364 | 1.299 | 0 | 6.100 |

| Urbanization Process | Urban | 1430 | 0.429 | 0.281 | 0.014 | 1 |

| Economic Development Level | GDP | 1430 | 10.822 | 0.526 | 9.304 | 12.281 |

| Urban Population Size | Population | 1430 | 5.891 | 0.711 | 3.008 | 8.136 |

| Social Security Level | Social Sec | 1430 | 14.025 | 0.945 | 11.786 | 17.452 |

| Urban Rule of Law Level | Law Soc | 1430 | 13.273 | 0.770 | 10.489 | 16.245 |

| Explanatory Variables | Explained Variables: Land Disputes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Urban | 0.206 *** | 0.082 *** | 0.073 *** | 0.255 *** | 0.080 *** |

| (0.017) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.136) | (0.027) | |

| GDP | −0.025 *** | −0.085 | −0.111 | −0.053 | |

| (0.100) | (0.098) | (0.098) | (0.102) | ||

| Population | 0.564 *** | 0.667 *** | 0.563 *** | 0.675 *** | |

| (0.124) | (0.123) | (0.124) | (0.123) | ||

| Social Sec | 0.351 *** | 0.415 *** | 0.412 *** | 0.432 *** | |

| (0.076) | (0.075) | (0.076) | (0.078) | ||

| Law Soc | 0.015 | −0.180 | −0.201 | −0.195 | |

| (0.125) | (0.126) | (0.126) | (0.129) | ||

| Market | −0.554 | ||||

| (0.058) | |||||

| IndStr | −0.285 | ||||

| (0.054) | |||||

| City Fixed Effects | No | No | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Year Fixed Effects | No | No | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Adj. R2 | 0.092 | 0.128 | 0.739 | 0.741 | 0.745 |

| N | 1430 | 1430 | 1430 | 1430 | 1430 |

| Selective Compensation | Comprehensive Land Price Compensation for The Area | Compensation for Multiples of Annual Production Value of Land Expropriated | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Law | 0 | 0 | 13 | 13 |

| Local Government Regulations | 1 | 1 | 10 | 12 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

You, W.; Dai, T.; Du, W.; Chen, J. Special Sacrifice and Determination of Compensation Standard for Land Expropriation in the Urbanization Process—A Perspective of Legal Practice. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12159. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912159

You W, Dai T, Du W, Chen J. Special Sacrifice and Determination of Compensation Standard for Land Expropriation in the Urbanization Process—A Perspective of Legal Practice. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12159. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912159

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Wei, Tianyu Dai, Wuqing Du, and Jiabai Chen. 2022. "Special Sacrifice and Determination of Compensation Standard for Land Expropriation in the Urbanization Process—A Perspective of Legal Practice" Sustainability 14, no. 19: 12159. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912159

APA StyleYou, W., Dai, T., Du, W., & Chen, J. (2022). Special Sacrifice and Determination of Compensation Standard for Land Expropriation in the Urbanization Process—A Perspective of Legal Practice. Sustainability, 14(19), 12159. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141912159