1. Introduction

To reduce the financial burden of household medical care, the Chinese government has established a basic medical insurance system. This system mainly comprises the basic medical insurance system for urban employees and the basic medical insurance system for urban and rural residents. For a long time, the registered residence has been a symbol of China’s resident status and can be understood as a registration system for population information. Registration is usually recorded by according to the basic situation of the residents; those living in urban and rural areas are divided into urban registered residents (that is, non-agricultural registered residents) and rural registered residents (that is, agricultural registered residents). The basic medical insurance system for residents also includes the new rural cooperative medical care system for rural registered residents and the basic medical insurance system for urban registered residents. Specifically, the employees’ basic medical insurance system is for groups with employment relations, and the employer and employee are forced to share the payment in a certain proportion every month during their work, so as to offset part of the medical expenses of employees when they are hospitalized. The basic medical insurance system for residents, with a proportion of the payments covered by the government and the rest by individuals, prepays the fees in advance to a certain proportion of the population with registered residence in the region, so as to offset the medical expenses of residents when they are hospitalized.

The National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference of 2019 focused heavily on the issue of social security. Among other issues, housing security has become a central topic of concern. President Xi Jinping also emphasizes in a report that “housing is used for living, not for speculation”. China’s housing security mainly covers the housing provident fund system and the affordable housing system. The housing provident fund system is mainly aimed at groups with employment relations. It is mandatory for employers and employees to share the payment in a certain proportion every month during their work, so as to offset part of the mortgage loans for employees to buy houses. The affordable housing system is aimed at low-income local registered residents, providing low-cost public rental housing or non-ownership housing at below-market prices. Housing security aims to enhance the living conditions of low- and middle-income residents. It should be pointed out that housing security can reduce the pressure of household housing mortgage loans or reduce the housing cost of low-income groups, promote the household’s disposable income to be more used for other consumption such as preventive health care expenditures [

1], and then reduce the probability of major diseases, to disperse the family medical economic risk. From this point of view, housing security has a complementary role to basic medical security.

According to the STATISTICAL COMMUNIQUE OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA ON THE 2020 NATIONAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT (

http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202102/t20210227_1814154.html (accessed on 28 February 2021)) published by the National Bureau of Statistics, the floating population is a special group, which usually refers to residents in other areas who live in a place for a period of time but are not recorded in the place. The existing literature shows that the basic medical insurance system can, to a certain extent, reduce the out-of-pocket medical expenses of the floating population and thus reduce the medical and financial burden of floating households. However, the strict household registration management system and the low compensation ratio make the effect of basic medical insurance on the economic risk dispersion of the rural registered floating population limited [

2]. In addition to its medical security, the housing security of the floating population is also a major concern. At present, China’s housing security system is constantly improving, and construction work is occurring at a rapid rate. Migrant workers with stable employment in cities have been included under the scope of the housing provident fund system, but most of those engaged in informal occupations have not paid the housing provident fund, and also do not have the application qualifications for affordable housing. Their meagre incomes also make it harder for them to purchase or rent a house in a city.

For most households in the world, health care, education, and housing are the main components of household expenditures. Among them, housing is a necessity for every household, and entails high expenditures. Since residents have a high probability of borrowing and lending for the purchase of housing, it will create financial risk for the whole household, especially those living in urban areas. At this point, if a household member suffers from a serious illness, the household will fall into poverty if the government does not have good policies for housing security and medical security. In China, the housing provident fund system can better offset household housing mortgage loans and reduce financial risk, and the affordable housing system can also alleviate residents’ financial stress by directly providing housing. Once residents’ housing, a necessary need, is addressed, they will be able to afford the financial burden of unanticipated serious illnesses. In addition to China, other countries with similar housing security policies include Singapore’s Central Provident Fund and Brazil’s Housing Development and Employment Guarantee Fund. This paper examines the relationship between housing security and medical security in China, so as to provide a basis for policy reform in developing countries.

China is chosen as the subject of this paper because although China has established housing security and medical security systems, their inconsistent levels of development result in a lack of synergy to effectively improve the lives of residents. At the same time, considering that residents in developing countries are more prone to poverty due to housing and serious illness, it is more socially valuable to target developing countries for the study. Therefore, this paper uses China to represent developing countries, and analyzes the relationship between housing security and medical economic risk using Chinese household data. This paper offers the following contributions: firstly, this paper extends the research on the factors influencing catastrophic health expenditures. Secondly, this paper takes the special group of the floating population as the research object and studies its related housing security and medical security policies, which not only have theoretical significance but also practical significance. Thirdly, this paper applies the econometric approach to describe the inter-relationship between housing security and catastrophic health expenditures, illustrating the correlation between the two. Our findings provide a policy reference for countries that have only housing security policies or medical security policies.

In summary, it is necessary to verify the influence of housing security on the family medical economic risk of the floating population. This paper is organized as follows. The following section provides a literature review; the third section introduces the variables, data and methods used; the fourth section presents our empirical results and the last section provides conclusions and recommendation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Literature Review on Housing Security

Housing security has become a major topic of concern, and academics and scholars in China and abroad have carried out detailed research on the issue. Rabe and Taylor [

3] held that the main factor that prevents people from settling in cities is the higher cost of living, especially in terms of the cost of housing. Fang et al. [

4] compared housing prices in China from 2003 to 2013 and found the average annual rate of growth in housing prices in first-tier cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen over the past 10 years could reach as high as 13.1%. Andrew [

5] found massive influxes of urban populations to increase housing prices in cities, increasing housing costs and inhibiting urbanization to a certain extent. Low- and middle-income individuals are thus often unable to purchase housing independently, making it essential for government departments to establish and implement a public service system of housing security.

With regard to housing security, previous studies have mainly focused on the following three areas.

- (1)

Housing security policy system design. Guo et al. [

6] proposed a two-stage evolutionary high dimensional multi-objective optimization algorithm and designed a novel framework and process of public policy for the rental housing market. Luo [

7] took China’s public rental housing (PRH) as the research object and found that the well-intended housing policy mainly proposed three measures: government procurement, new financial arrangements and guided service contents. Furthermore, informed by ideas of social constructionism, which emphasises the politics of housing, McKee et al. [

8] emphasized the need for greater geographical sensitivity through an analysis of policy narratives.

- (2)

Factors that influence housing satisfaction. While research on this topic has been conducted for a long time, the results are varied. For example, Nguyen et al. [

9] concluded from 450 respondents living in their own affordable apartments in urban Hanoi that housing satisfaction is positively associated with household income but negatively related to education. In addition, the design of the apartment, the price of the building, the location of the house and the quality of the environment were all major factors that affect housing satisfaction. Kshetrimayum et al. [

10] surveyed 981 households in three different slum rehabilitation housing areas spatially spread across Mumbai. The causal model indicated that residential satisfaction was significantly determined by internal conditions of dwelling resulting from design, community environment and access to facilities.

- (3)

The effectiveness of housing security policies. Elsinga et al. [

11] argued that the explicit combination of moral values and housing policy and design is found neither in academic research on housing nor in the philosophical literature. Therefore, inclusiveness, sustainability and autonomy should be taken into account when discussing the value of housing security. Sinai [

12] presented his own views on how to evaluate housing policies and argued that it should be based on whether policies can improve the total housing area available. Frick et al. [

13] compared the housing security policies of five European countries (Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy and the United Kingdom) and found that they can all reduce income inequality.

2.2. Literature Review on Medical Economic Risk

A family exposed to medical economic risk can be subjected to catastrophic health expenditures, resulting in economic losses caused by disease that greatly reduce consumption and quality of life. Several scholars have discussed ways to measure such health expenditures with varied results [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. According to relevant regulations established by the World Health Organization, when a family’s medical expenditures reach or exceed 40% of total expenditures excluding food expenditures, these can be regarded as catastrophic health expenditures.

Previous studies on family medical economic risk have mainly focused on the relationship between medical insurance security and catastrophic health expenditures. Albert Opoku Frimpong et al. [

20] found that in Ghana, households with National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) coverage exited catastrophic health expenditures 19 days (30 days) earlier than those without NHIS coverage. Similarly, Sheng-wen Zhao et al. [

21] revealed that China’s catastrophic medical insurance (CMI) perfectly meets the pursued policy objectives and significantly reduced the incidence of catastrophic health expenditures. In addition, Esso-Hanam [

22] found that different types of health insurance would affect family medical economic risk. The results showed that households with public insurance spent a higher proportion of their total monthly nonfood expenditures on health care than those with private insurance. However, Zhang et al. [

23] argued that such an effect on China’s basic medical insurance systems would achieve strategic goals only in certain regions rather than across the country as a whole. In addition, some scholars considered that income level is the most important factor influencing the occurrence of catastrophic health expenditures [

24,

25,

26]. On the one hand, when household income is low, patients had to delay the medical treatment because they cannot pay for the full amount of medicine, and the resulting disease deterioration may make the required treatment more and more expensive, thus incurring catastrophic health expenditures; on the other hand, health problems can reduce personal labor participation rate, which in turn affects patients’ human capital accumulation and reduces household disposable income and contributions to catastrophic medical expenditures.

2.3. Literature Review on Housing Security and Medical Economic Risk

Housing is one of the most important assets and durable goods of residents, and it is also the main evaluation indicator to judge the success of individuals and the happiness of families. Currently, there are few articles on housing security and medical economic risk. Brucker and Garrison [

27] used 2013–2016 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data to confirm that non-elderly Social Security Disability Insurance (DI) and/or Supplement Security Income (SSI) participants in HUD-assisted rental housing programs face unique health disparities. Atalay et al. [

28] used Australian household data from 2001–2015 to examine the relationship between house prices and health. The results showed that the increase in local house prices had a positive effect on the physical health of homeowners and a negative effect on the physical and mental health of renters. Xu and Wang [

29] used individual-level health data from 2000 to 2011 in China to obtain the same conclusion. Some scholars have also found the opposite, suggesting that rising house prices can improve residents’ use of health care and increase health inputs and medical insurance expenditures [

30,

31].

In recent years, the proportion of housing consumption in the consumption structure has been increasing due to the rise in housing prices. Although it has increased the asset value of residents’ housing, it has also crowded out other household consumption, the most important of which is health consumption [

32,

33]. However, a good housing security policy will significantly alleviate the burden of health care access for residents. Especially for the floating population, housing is one of the basic living conditions for their survival and development in the city. However, the restrictions of the household registration system prevent them from enjoying the benefits of the urban housing allocation system [

34]. The disadvantaged conditions of the floating population in terms of access to housing, type of housing and living environment all have a negative impact on health [

35,

36]. In turn, a person’s ill health inevitably brings about high medical expenditures and thus medical economic risks for the whole family [

37]. Housing security greatly affects people’s livelihoods and is a common problem faced by governments around the world. Therefore, it is of crucial importance to estimate how housing security affects family medical economic risk to establish better housing and medical security systems.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Variables

We use housing provident fund and per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing as explanatory variables for measuring housing security levels, and catastrophic health expenditures as the explained variable, which is a key indicator of family economic risk. According to the book ‘Health systems performance assessment: debates, methods, and empiricism’, published by the World Health Organization in 2003 [

38], health expenditures are defined as catastrophic when a household’s out-of-pocket payments are greater than or equal to 40% of its capacity to pay. Among them, household capacity to pay is measured as total expenditures excluding food expenditures. Given that the above method is an authoritative way to calculate “catastrophic health expenditures” and is used by many scholars [

39,

40,

41], this paper also calculates the explanatory variables accordingly.

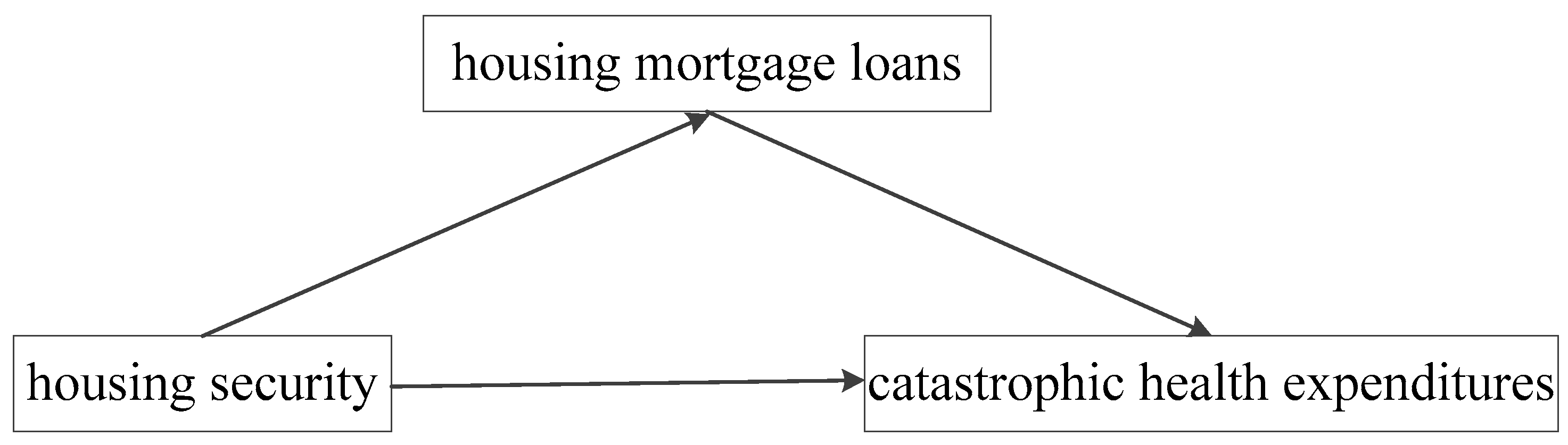

When total household wealth is constant, household housing expenditures and preventive health care expenditures are substitutionally related, i.e., the more household housing expenditures, the less preventive health care expenditures. In light of this, a household’s having or not having a housing mortgage loan will affect its preventive health care expenditures, which in turn will have an impact on the occurrence of household catastrophic health expenditures. Therefore, this paper explores the mechanism of the effect of housing security levels on catastrophic health expenditures, using the amount of the household’s housing mortgage loans as a mediating variable.

The control variables focus on family and individual characteristics. Family education, health and medical insurance levels are used to estimate family characteristics. Generally, the higher the level of education, the higher the degree of awareness of medical economic risk and the lower the probability of catastrophic health expenditures [

42]. Medical expenditures may increase as health conditions worsen [

43]. More importantly, we divide medical insurance into commercial and social medical insurance to not only reflect overall levels of family medical insurance but also reflect the impact of the two different forms of medical insurance on catastrophic health expenditures. In addition, considering the possible nonlinear effect of medical insurance coverage on family medical economic risk, two variables—namely quadratic commercial medical insurance level and quadratic social medical insurance level—are constructed. Individual characteristics are measured using four variables. Registered residents are divided into agricultural and non-agricultural residents. For household age, its square value is set as a new variable to reflect the life cycle. The last variable used to measure individual characteristics is marital status. The specific variable indicators used are as follows in

Table 1.

3.2. Data and Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Chinese Family Panel Studies (CFPS), which are a series of large-scale nationwide and multidisciplinary social tracking surveys conducted by Peking University’s Institute of Social Science Survey (ISSS). In China, there are many similar databases. The advantage of the CFPS database is that it is unbiased in terms of sample selection and survey content. For example, the China Labor-force Dynamic Survey (CLDS) database is a comprehensive database with the labor force as the survey target. The China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) database collects information about household finance at the micro level. The China Health and Retirement LongitudinalStudy (CHARLS) database surveys the social, economic, and health status of middle-aged and older adults in China, aged 45 and older. However, CFPS database uses a multi-stage, probability proportional to size (PPS) approach to drawing micro-samples from 31 provinces and cities each year. The survey covers social, economic, demographic, educational, and health changes in China. Thus, CFPS covers the full range of Chinese household, individual, and community variable data needed for this paper. For example, the individual questionnaire includes “whether to provide housing fund”, and the household questionnaire includes “the amount of annual household expenditure”, etc. These representative data serve as reliable data for our work. Since the 2020 data currently published by CFPS includes only the individual and juvenile databases and lacks the family and community databases, we here provide an analysis of panel data for 2012, 2014, 2016 and 2018 to describe the influence of housing security on the family medical economic risk of the floating population. This paper selects samples with different places of residence and household registration according to QA302 “current household registration place” in the questionnaire as the floating population. In addition, approximately 40% of the annual CFPS samples are the floating population, indicating that CFPS is representative and feasible as a data source for this study. To ensure the objectivity of our empirical analysis, missing data samples were removed, leaving us with a valid sample of 8124.

Since the values of the explained variable in this paper are discrete data, regression by the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method will cause bias in the results. Therefore, we referred to Abdel-Rahman et al. [

44] and Sun and Lyu [

45] using a panel Probit regression to explore the relationship between the core explanatory variables and the explained variable. We also fit a mediating effect model and used this model to examine the influence mechanism of housing security and catastrophic health expenditures.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Variables

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for variables of our sample of 8124. We find that 8.49% of families have been exposed to medical economic risk. Less than 1/5 have paid housing provident fund. After logarithm application, per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing is measured at a mean of 5.6667 and a standard deviation of 0.4324. From the mean value, education and health levels of 8124 respondents are not high, and average insurance levels are low. The sample is mostly composed of agricultural residents and roughly a third (70.83%) are married. Moreover, the respondents have a mean age of 50. The housing mortgage loans range from 0 to 14.2008 after taking the logarithm, indicating a large variation in housing mortgage loans between households.

4.2. Benchmark Regression

Considering the possible endogeneity problem of the benchmark regression, an instrumental variable is found for each of the two core explanatory variables in this study. Although the housing property rights forms are very complicated in China, residents can apply for housing mortgage loans only after they have complete housing property rights. At this time, the residents can withdraw the housing provident fund to repay the loans. In addition, the status of housing property rights does not affect family health decision-making and medical expenditure. Therefore, the instrument variable of the housing provident fund is based on FQ1 of the CFPS questionnaire: “Who owns the property right of your existing house”. In China, affordable housing policy is identified as a local matter, so affordable housing expenditures are provided by the local government. Because of the spatial spillover characteristics of government fiscal expenditures, local affordable housing expenditures are often influenced by the expenditures of neighboring local governments, and this government action does not affect households’ health care decisions. Therefore, the average per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing in other provinces qualifies as an instrumental variable for another core explanatory variable in this research, i.e., the instrumental variable of per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing.

Since the explained variable in this paper is a dummy variable, the benchmark regression and endogeneity test were performed using the panel Probit and two-stage IV probit respectively. In addition, this paper added time fixed-effects and community-level regional fixed-effects to the regressions. As shown in

Table 3, the results of the endogeneity test are significant and the coefficients are consistent with the benchmark regression results, indicating that the conclusions of this research still hold after excluding the endogeneity problem. Specifically, the regression results for both core explanatory variables have passed the significance testing. The payment of housing provident fund can effectively reduce the incidence of catastrophic health expenditures for the floating population, but per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing will significantly increase family medical economic risk.

For the control variables, both education level and health level can reduce the occurrence of catastrophic household medical expenditures, which may be because people with higher education levels also have a higher awareness of health risks and disease prevention, and people with high self-rated health scores are less likely to suffer from major diseases. In the full sample, participation in both commercial medical insurance and social medical insurance can effectively alleviate poverty due to illness; however, increased intensity of medical insurance coverage may result in moral hazard leading to excessive medical spending behavior by household members. Registered resident status has a significant influence, meaning that agricultural residents have a higher probability of incurring catastrophic health expenditures compared to non-agricultural residents, which may be due to their lower incomes and policy preferences. The other two variables, namely marital status and household age, are not significantly related to the explained variable.

4.3. Robustness Test

To ensure the robustness of the benchmark regression results, two tests are examined in this paper. The first approach is to apply different methods to re-regress the data. Specifically, considering the problem of selection bias in the sample, this paper applies the Propensity Score Matching (PSM) method, which uses propensity score values to find individuals with the same or similar background characteristics from the control group for each individual in the treatment as a control, thus minimizing the interference of other confounding factors. In addition, because the explained variable in this paper is a dummy variable, the panel Logit method is added to the robustness test in addition to the panel Probit method applied in the benchmark regression. The second approach is to select different thresholds for catastrophic health expenditures, thus replacing the explained variable in the benchmark regression. Based on the World Health Organization definition, health expenditures are considered to be catastrophic at 40% of household non-food expenditures. In the robustness test, the thresholds of 20% and 50% are introduced and regressed, respectively. The results are shown in

Table 4.

From

Table 4, it can be seen that the direction of the regression coefficients as well as the significance of the regression coefficients remain consistent with the previous paper whether replacing the catastrophic health expenditures threshold or changing the measurement method, indicating that the results of the benchmark regression in this paper are robust.

4.4. Heterogeneity Test

Table 4 shows the regression results of the heterogeneity test for samples with different household register and income levels. As can be seen from columns (1) and (2), both regression coefficients of housing provident fund are significantly negative, while the regression coefficients of the per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing are different, with a positive result for agricultural residents and a negative result for non-agricultural residents. In fact, agricultural residents tend to migrate from rural to urban areas. In the process of urbanization, this group of people needs good housing security and medical care more as a floating population. The empirical results show that the housing provident fund can reduce the medical economic risk of agricultural residents, while the affordable housing system does not. As can be seen, the above results seriously contradict the original purposes of the indemnification housing system. For the control variables, compared with the full-sample regression results in the benchmark regression (

Table 3), the findings differ for only two variables, namely commercial medical insurance level and quadratic social medical insurance level. Specifically, regardless of the household commercial medical insurance coverage level, commercial medical insurance cannot mitigate family medical economic risk for non-agricultural residents. In contrast, for agricultural residents, the result of quadratic social medical insurance level is significantly negative, indicating that enrolling in more social medical insurances will reduce the probability of incurring catastrophic health expenditures.

The regression results in columns (3), (4) and (5) of

Table 5 show that the impact of housing security on catastrophic health expenditures varies by income levels. While the effects of housing provident fund for middle-income residents are not significant, it generally reduces the incidence of catastrophic health expenditures. Since the housing provident fund varies with the salary, middle-income residents pay a middle level of housing provident fund. However, their housing expenses are not necessarily at the middle level. According to the results, their housing provident fund is not effective in mitigating family economic risk and may instead increase the financial burden. In addition, except for the non-significant results of the high-income samples, the results of the other variable representing housing security, i.e., per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing, indicate that per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing increases the incidence of catastrophic health expenditures. For high-income samples, housing expenditures do not represent a large proportion of overall household expenditures. Affordable housing policy mainly targets the middle- and low-income groups, so this result is not significant. Regarding the control variables, compared to the full-sample regression, the effect of increased education level on health expenditures was not significant for low-income residents. The results of a significantly negative coefficient for family health level remained consistent across the low- and middle-income samples. Whether it is commercial medical insurance or social medical insurance, the guarantee function for the low-income samples is higher, which can effectively relieve the family medical financial burden. Moreover, this phenomenon exists regardless of the intensity of medical insurance coverage. However, middle- and high-income groups tend to have more diverse health needs and prefer more effective and expensive treatments, resulting in increased health expenditures. The results of the remaining variables are the same as the regression results in the benchmark regression (

Table 3).

4.5. Influence Mechanism Test

To better understand the impact of housing security on household medical economic risk, we construct a simple health economic model. First, we consider the situation in which the household has no mortgage loans or housing rent. Assuming that the representative household only includes housing expenditures

and preventive health care expenditures

, then the utility function of the household is

. The value of household wealth is

, the housing price is set as unit price 1, and the price of preventive health care expenditures is

. The utility of a representative household is maximized as follows:

Constructing the Lagrange’s equations from Equations (1) and (2):

The first-order conditions can be obtained:

The equilibrium conditions can be obtained from Equations (4) and (5):

is the shadow price of

and

. Equation (6) represents the marginal utility substitution rate of household housing expenditures and preventive health care expenditures when there is no mortgage loan or housing rent.

Now consider the existence of mortgage loans or housing rent for a representative household. Assuming that the housing expenditures is mortgaged for

months, the monthly repayment amount is

. Then, the representative household utility maximization problem is:

Constructing the Lagrange’s equations from Equations (7) and (8):

The first-order conditions can be obtained:

The equilibrium conditions can be obtained from Equations (10) and (11):

is the shadow price of housing mortgage loans. Equation (12) represents the marginal utility replacement rate of household housing expenditures and preventive health care expenditures when there is a mortgage loans or housing rent.

As can be seen from Equations (12) and (6), compared to the case of an unsecured loan, housing expenditure with a mortgage loan is a higher substitute for preventive health care expenditures. If Equation (12) is subtracted from Equation (6), the degree

to be squeezed out of preventive health care expenditures can be calculated.

Through the above derivation, we can know that the reduction of household preventive health care expenditures will lead to an increase in the risk of major diseases of household members, resulting in high medical expenses .

Thus, we assume that high medical costs

and

have a positive linear relationship:

is the constant term and

is the coefficient between

and

. Combining Equations (13) and (14), it can be seen that if housing security can reduce the shadow price

of the household’s housing mortgage loans and increase the preventive health care expenditures, it can reduce the household’s risk of major diseases and the probability of catastrophic health expenditures. In light of this, we argue that the housing security levels can affect the family medical economic risk by increasing or decreasing the amount of housing mortgage loans as shown in

Figure 1. Therefore, this paper will further apply the econometric approach to test this hypothesis of the influence mechanism.

The model that we use to estimate this mechanism is very similar to those used by other researchers on the same issue [

46]. According to the step-test regression coefficient method proposed by Baron and Kenny [

47], the mediating effect model is divided into the following three main steps. First, the explanatory variables and catastrophic health expenditures are regressed. Second, the relationship between housing mortgage loans and the explanatory variables is elucidated. Finally, we regress the explanatory variables, housing mortgage loans and catastrophic health expenditures. If the results are significant, a mediating effect exists. The specific regression model is written as follows:

,

,

and

respectively refer to housing provident fund, per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing, housing mortgage loans and the control variables;

,

, and

, respectively, refer to error term, and Regional Fixed-effects and Time Fixed-effects.

Table 6 summarizes our estimation of influencing mechanisms. As can be seen, the coefficients of both core explanatory variables and mediating variable are significant, indicating that household housing mortgage loans have played the mediating role between housing security levels and catastrophic health expenditures. Specifically, the total effect of housing provident fund contribution on catastrophic health expenditures is 0.0392, of which, the direct effect is 0.0140. The mediating effect of the housing provident fund in decreasing the incidence of catastrophic health expenditures by reducing the housing mortgage loans is 0.0264 (0.3170

0.0834), and it accounted for 67.4% of the total effect. According to the results of per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing, the total effect is 0.0197 and the direct is 0.0071. The mediating effect of per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing in promoting the incidence of catastrophic health expenditures by increasing the housing mortgage loans is 0.0136 (0.1632

0.0834), and it accounted for 69.0% of the total effect. In summary, the empirical results confirm the hypothesis in

Figure 1 that housing security policies do affect family medical economic risk through housing mortgage loans for the floating population. The impact of different types of housing security policies can also vary.

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

The present work estimates the influence of housing security on family medical economic risk for the floating population. Panel data that support the findings of this study are available from the Chinese Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Applying the panel probit method, the results of our benchmark regression show that for the floating population, the payment of housing provident fund can effectively reduce the incidence of catastrophic health expenditures. On the contrary, per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing can significantly increase family medical economic risk. The above findings passed the endogeneity and robustness tests. Heterogeneity tests based on the household register and income level indicate that impacts of housing security vary across residents’ household registration statuses and income levels. Especially for agricultural and low- and middle-income residents, the effects of per capita financial expenditure on affordable housing run contrary to what we initially expected. Compared with other studies, the similarity is that both housing security and medical insurance can reduce family medical economic risk. Nevertheless, the influence mechanism is different, that is, medical insurance is a direct mechanism and housing security is an indirect mechanism, which has been verified by a mediating effect model, showing that housing security affects family medical economic risk by reducing or increasing the housing mortgage loans. As the two most prominent housing security systems in China, our research confirms that the housing provident fund system has indeed enhanced the affordability of low- and middle-income workers to purchase a house through the above mechanism, thereby alleviating poverty and re-poverty caused by disease. However, our findings on the affordable housing system are different from other studies, which do not show effective relief of the housing pressure of the floating population. Specifically, the mediating effect of the housing provident fund accounts for 67.4% of the total effect, and the mediating effect of the affordable housing system accounts for 69.0% of the total effect.

At present, the construction of housing security in China is advancing on a broad scale, requiring not only a high degree of government financial investment but also a high level of social capital participation. It is also necessary to improve the efficiency of capital use. While household registration reforms have made it easier for the floating population to enter cities, due to this population’s low income and education levels and limited social networks, it still experiences barriers to equal housing and medical security. From the conclusions drawn, we make the following policy recommendations. First, it is necessary to optimize and upgrade the guarantee function of the housing provident fund system. The government should promote enterprises to implement the housing provident fund system for employees by formulating relevant preferential policies to improve the accessibility of the system. At the same time, contribution and treatment standards should be flexibly set to ease the pressure of housing for the floating population and reduce their mortgage loans. In the process of policy reform, the policy should be formulated in a way that varies from city to city. For example, in first- and second-tier cities, the government should focus on using the housing provident fund to pay rent, while in third-tier cities, the housing provident fund should be used more for the purchase of housing. Second, the coverage of the affordable housing policy should continue to be expanded. At present, a large number of floating population working and living in cities and towns are excluded from the coverage of the affordable housing policy, so localities should establish relevant systems to meet the housing needs of the floating population and prevent medical economic risk due to the financial burden of housing. For example, employment and residence for more than five years should be taken as an important basis for settlement, and priority should be given to solving the problem of settlement for the floating population with employment and residence for more than five years. In addition, considering that the post-80s and post-90s floating population is the core group for cities to realize talent accumulation and bring into play the demographic dividend, the reform of the housing system should focus on this group of people. Third, considering the complementary role of housing security to medical security, it is important to promote the coordinated development of the medical insurance system and the housing security system. The development of China’s housing system has lagged too far behind the medical insurance system, and these two systems are segregated from each other. Therefore, in order to solve the housing and medical security problems of the floating population as much as possible, the central government should formulate a coordinated supervisory policy to increase the support role for the floating population, especially the low-income group, and ensure fairness and sustainability of the security system.

On the whole, compared with the existing literature, this research effectively argues that housing security can, to some extent, complement basic health insurance by alleviating the pressure of housing mortgage loans for the floating population and reducing their medical economic risk. The above conclusions not only have theoretical and practical significance for the establishment of the security system for the floating population in China but also provide an effective reference for the development of housing and medical security systems in other countries. However, there are still some shortcomings in this paper. First, the mechanism of the impact of housing security on the medical economic risk for the floating population needs to be explored in depth. Second, this research does not use micro-survey data on the floating population, which is more relevant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L. and Y.-T.Z.; methodology, T.L. and Y.-T.Z.; software, Y.-T.Z.; validation, T.L.; formal analysis, T.L.; investigation, H.-W.Z. and P.-J.L.; resources, T.L.; data curation, Y.-T.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L. and Y.-T.Z.; writing—review and editing, T.L., Y.-T.Z., H.-W.Z. and P.-J.L.; visualization, H.-W.Z. and P.-J.L.; supervision, T.L.; project administration, T.L.; funding acquisition, T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Nature Science Foundation of China, grant number 71904094 and Postdoctoral Science Foundation, grant number 2021M700413.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, Z.X.; Zhai, M.R. An empirical analysis on the impact of housing security on residents’ consumption. Commer. Res. 2012, 68, 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, L.J.; Chen, C.P.; Wang, W.; Chen, H. How migrants get integrated in urban China—The impact of health insurance. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 272, 113700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe, B.; Taylor, M.P. Differences in Opportunities? Wage, Employment and House-Price Effects on Migration. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2012, 74, 831–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Gu, Q.; Xiong, W.; Zhou, L.-A. Demystifying the Chinese Housing Boom. NBER Macroecon. Annu. 2016, 30, 105–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, M. Regional market size and the housing market: Insights from a new economic geography model. J. Prop. Res. 2012, 29, 298–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, L.; Xie, H.; Shi, W. Improved Multi-Objective Optimization Model for Policy Design of Rental Housing Market. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Heijden, H.V.D.; Boelhouwer, P.J. Policy design and implementation of a new public rental housing management scheme in China: A step forward or an uncertain fate? Sustainability 2020, 12, 6090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, K.; Muir, J.; Moore, T. Housing policy in the UK: The importance of spatial nuance. Hous. Stud. 2016, 32, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.T.; Tran, T.Q.; Van Vu, H.; Luu, D.Q. Housing satisfaction and its correlates: A quantitative study among residents living in their own affordable apartments in urban Hanoi, Vietnam. Int. J. Urban. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 10, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetrimayum, B.; Bardhan, R.; Kubota, T. Factors Affecting Residential Satisfaction in Slum Rehabilitation Housing in Mumbai. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsinga, M.; Hoekstra, J.; Sedighi, M.; Taebi, B. Toward Sustainable and Inclusive Housing: Underpinning Housing Policy as Design for Values. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinai, T.; Waldfogel, J. Do low-income housing subsidies increase the occupied housing stock? J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 2137–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.R.; Grabka, M.M.; Smeeding, T.M.; Tsakloglou, P. Distributional effects of imputed rents in five European countries. J. Hous. Econ. 2010, 19, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Peng, X.; Shen, M. Concentration and Persistence of Healthcare Spending: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, A. Measuring catastrophic medical expenditures: Reflections on three issues. Health Econ. 2019, 28, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, J.; Majdzadeh, R.; Mills, A.; Hanson, K. A dominance approach to analyze the incidence of catastrophic health expenditures in Iran. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 285, 114022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahid, Y.F.; Hossein, M.M.; Ali, D. Measuring catastrophic health expenditures and its inequality: Evidence from Iran’s health transformation program. Health Policy Plan. 2019, 4, 316–325. [Google Scholar]

- Si, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Su, M.; Ma, M.; Xu, Y.; Heitner, J. Catastrophic healthcare expenditure and its inequality for households with hypertension: Evidence from the rural areas of Shaanxi Province in China. Int. J. Equity Health 2017, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, C.; Barros, P.P. Catastrophic healthcare expenditure—Drivers and protection: The Portuguese case. Health Policy 2014, 115, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, A.O.; Amporfu, E.; Arthur, E. Effect of the Ghana National Health Insurance Scheme on exit time from catastrophic healthcare expenditure. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2021, 33, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.-W.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Dai, W.; Ding, Y.-X.; Chen, J.-Y.; Fang, P.-Q. Effect of the catastrophic medical insurance on household catastrophic health expenditure: Evidence from China. Gac. Sanit. 2019, 34, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esso-Hanam, A. Does the type of health insurance enrollment affect provider choice, utilization and health care expenditures? BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Cheng, X.; Tolhurst, R.; Tang, S.; Liu, X. How effectively can the New Cooperative Medical Scheme reduce catastrophic health expenditure for the poor and non-poor in rural China? Trop. Med. Int. Health 2010, 15, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vahedi, S.; Razapour, A.; Khiadi, F.F.; Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Javan-Noughabi, J.; Almasianika, A.; Ghanbari, A. Decomposition of socioeconomic inequality in catastrophic health expenditure: An evidence from Iran. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 8, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viramgami, A.; Upadhyay, K.; Balachandar, R. Catastrophic health expenditure and health facility access among rural informal sector families. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 8, 1325–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, X.C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.Y. Progress on catastrophic health expenditure in China: Evidence from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) 2010 to 2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4775. [Google Scholar]

- Brucker, D.L.; Garrison, V.H. Health disparities among Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income beneficiaries who participate in federal rental housing assistance programs. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 101098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, K.; Edwards, R.; Liu, B.Y. Effects of house prices on health: New evidence from Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 192, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, F. The health consequence of rising housing prices in China. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2022, 200, 114–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, A. Wealth Effects, Local Area Attributes, and Economic Prospects: On the Relationship between House Prices and Mental Wellbeing. Rev. Income Wealth 2013, 61, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichera, E.; Gathergood, J. Do Wealth Shocks Affect Health? New Evidence from the Housing Boom. Health Econ. 2016, 25, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disney, R.; Gathergood, J. House Prices, Wealth Effects and Labour Supply. Economica 2017, 85, 449–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelino, M.; Schoar, A.; Severino, F. House prices, collateral, and self-employment. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 117, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Yang, H.; Fu, M. Settlement intention characteristics and determinants in floating populations in Chinese border cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 39, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Su, S. Neighborhood housing deprivation and public health: Theoretical linkage, empirical evidence, and implications for urban planning. Habitat Int. 2016, 57, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Hui, E.C.-M. Housing prices, migration, and self-selection of migrants in China. Habitat Int. 2021, 119, 102479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Evans, D.B.; Kawabata, K.; Zeramdini, R.; Klavus, J.; Murray, C.J. Household catastrophic health expenditure: A multicountry analysis. Lancet 2003, 362, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Health Systems Performance Assessment: Debates, Methods and Empiricism; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; pp. 565–566. [Google Scholar]

- Kavosi, Z.; Rashidian, A.; Pourreza, A.; Majdzadeh, R.; Pourmalek, F.; Hosseinpour, A.R.; Mohammad, K.; Arab, M. Inequality in household catastrophic health care expenditure in a low-income society of Iran. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kockaya, G.; Oguzhan, G.; Çalşkan, Z. Changes in Catastrophic Health Expenditures Depending on Health Policies in Turkey. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 614449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.-Y.; Shi, J.-F.; Fu, W.-Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.-X.; Chen, W.-Q.; He, J. Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Its Determinants Among Households With Breast Cancer Patients in China: A Multicentre, Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 704700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, M. Catastrophic health expenditures and its inequality in elderly households with chronic disease patients in China. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogo, M. Portfolio choice in retirement: Health risk and the demand for annuities, housing, and risky assets. J. Monetary Econ. 2016, 80, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahman, S.; Shoaeb, F.; Fattah, M.N.A.; Abonazel, M.R. Predictors of catastrophic out-of-pocket health expenditure in rural Egypt: Application of the heteroskedastic probit model. J. Egypt. Public Health Assoc. 2021, 96, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Lyu, S. The effect of medical insurance on catastrophic health expenditure: Evidence from China. Cost Eff. Resour. Alloc. 2020, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Z.L.; Ye, B.J. A moderated intermediary model test: Competition or substitution? Acta Psychol. Sin. 2014, 46, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).