Understanding Politeness in an Online Community of Practice for Chinese ESL Teachers: Implications for Sustainable Professional Development in the Digital Era

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Background

2.1. Teacher Development through Online Communities

2.2. Conveyance of Politeness

3. The Study

3.1. Context of the Study

3.2. Participants

3.3. Data Sources

3.4. Procedure, Analytical Framework and Method of Analysis

3.5. Ethical Considerations

4. Findings

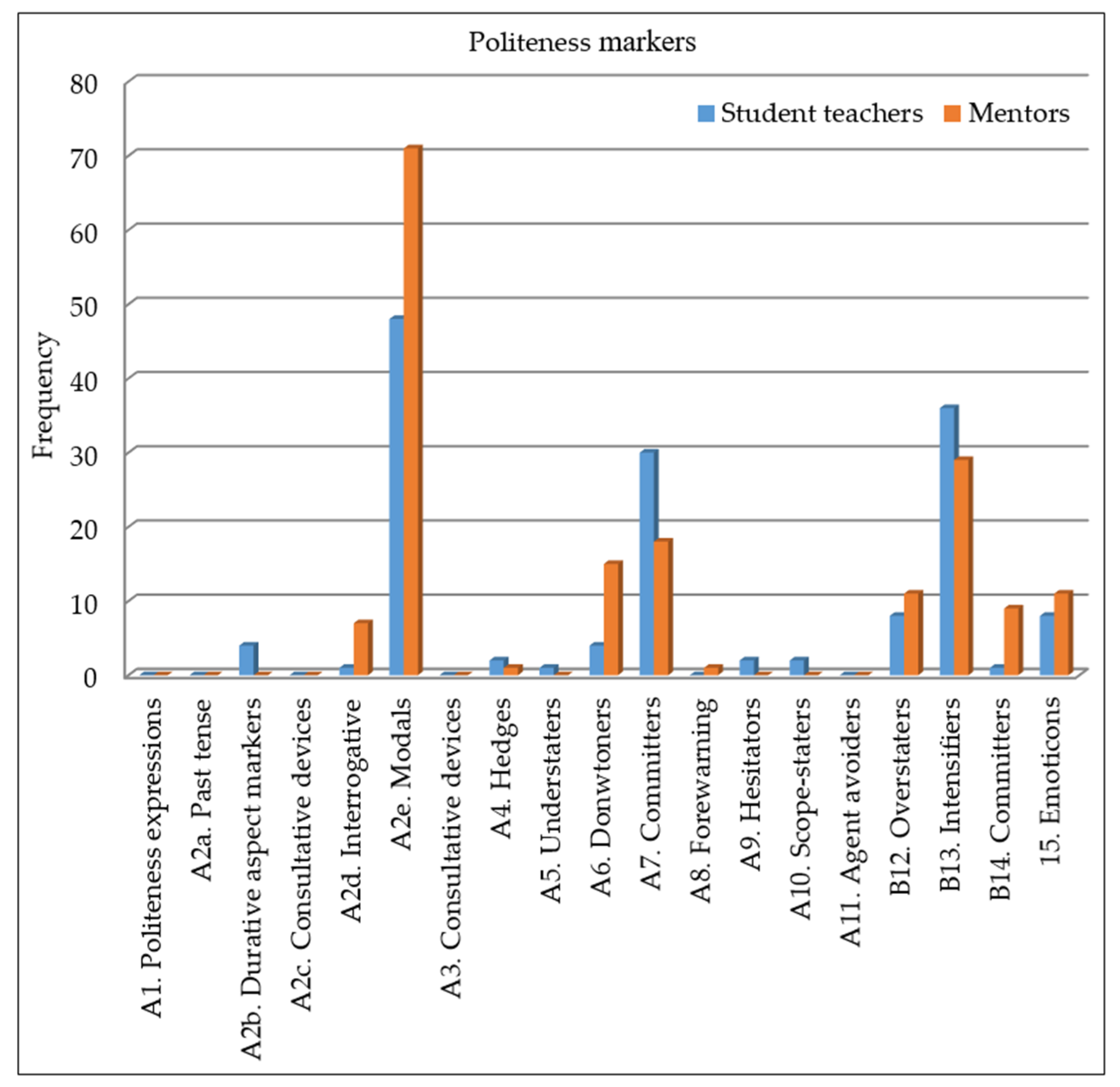

4.1. RQ1: Use of Politeness Markers by the Student Teachers and Their Mentors When Giving Suggestions and Making Evaluations

4.2. RQ2: Factors Contributing to the Signalling of Politeness in Interactive Commentaries of the Online CoP for Teachers

4.2.1. Perceived Need for Relationship Building in the Online Community

4.2.2. The Hierarchical Relationship between Mentors and Mentees

4.2.3. The Complex Nature of Teaching and Learning

4.2.4. Academic Nature of the Online CoP

4.2.5. Lack of Non-Verbal Cues in Online Discussions

4.2.6. Semantic Knowledge and Writing Style of Second Language Learners

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Politeness and Chinese Culture

5.2. Instilling L1 Culture in an L2 Online CoP for Teacher Development

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Sample Interview Questions

- How would you define your role or responsibilities in the blog? How about the roles of the other blog members?

- What kind of image do you like to project when interacting with other members of the blog? Why?

- How would you describe your relationship with the other members of the blog?

- Do you think your status is different from that of your fellow student teachers/mentors? Why or why not?

- What are some of the important issues to consider when it comes to interacting with others in the blog?

- Do you think it is important to pay special attention to word choice when interacting with others in the blog? Why or why not?

- How do you usually evaluate the ideas posted by other members of the blog? How do you go about making suggestions?

- It seems to me that modals such as “may” and “can” are often seen in the comments and responses you posted. Why is that?

- It is interesting to note that you often use such expressions as “maybe” and “perhaps” when making suggestions on the blog. Examples include “Maybe you can consider giving them some challenging topics?”, and “Perhaps you can write down some vocabulary items on the board?” Why did you choose these expressions?

- Are there any other comments you would like to add?

References

- Pan, Y. Politeness in Chinese Face-to-Face Interaction; Ablex Publishing: Stamford, CT, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-1-56750-493-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zembylas, M. Adult learners’ emotions in online learning. Distance Educ. 2008, 29, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, E.; Chung, E. A study of non-native discourse in an online community of practice (CoP) for teacher education. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2016, 8, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, S.W.P. Establishing professional online communities for world language educators. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2020, 53, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, E.; Klecka, C.L.; Lin, E.; Wang, J.; Odell, S.J. Learning to teach: It’s complicated but it’s not magic. J. Teach. Educ. 2011, 62, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E. Eleven factors contributing to the effectiveness of dialogic reflection: Understanding professional development from the teacher’s perspective. Pedagog. Int. J. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E.; McDermott, R.A.; Snyder, W. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1-57851-330-7. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, B.; Hramiak, A. A discourse analysis of trainee teacher identity in online discussion forums. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2010, 19, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, S. Unspoken social dynamics in an online discussion group: The disconnect between attitudes and overt behavior of English language teaching graduate students. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2013, 61, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallert, D.L.; Chiang, Y.V.; Park, Y.; Jordan, M.E.; Lee, H.; Cheng, A.J.; Chu, H.N.R.; Lee, S.; Kim, T.; Song, K. Being polite while fulfilling different discourse functions in online classroom discussions. Comput. Educ. 2009, 53, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, P. Doing Pragmatics, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-138-54948-7. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Chen, Y.; Kim, M.; Chang, Y.; Cheng, A.; Park, Y.; Bogard, T.; Jordan, M. Facilitating or limiting? The role of politeness in how students participate in an online classroom discussion. In 55th Yearbook of the National Reading Conference; Hoffman, J.V., Schallert, D.L., Fairbanks, C.M., Worthy, J., Maloch, B., Eds.; National Reading Conference: Oak Creek, WS, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-1-893591-08-0. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, E. Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face-to-Face Behavior; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982; ISBN 978-0-394-70631-3. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, R.J. Politeness; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-521-79406-0. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P.; Levinson, S.C. Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987; ISBN 978-0-521-31355-1. [Google Scholar]

- House, J.; Kasper, G. Politeness markers in English and German. In Conversational Routine; Coulmas, F., Ed.; De Gruyter Mouton: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 157–186. ISBN 9789027930989. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöström, J.; Ågerfalk, P.J.; Hevner, A.R. Scrutinizing privacy and accountability in online psychosocial care. IT Prof. 2017, 19, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copland, F. Negotiating face in feedback conferences: A linguistic ethnographic analysis. J. Pragmat. 2011, 43, 3832–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donaghue, H. Relational work and identity negotiation in critical post observation teacher feedback. J. Pragmat. 2018, 135, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikandar, A.; Hussain, N. Power and hegemony in research supervision: A critical discourse analysis. J. Educ. Educ. Dev. 2018, 5, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 7th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-415-58336-7. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Flor, A. The use and function of “please” in learners’ oral requestive behavior: A pragmatic analysis. J. English Stud. 2009, 7, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, B. Emoticons as a medium for channeling politeness within American and Japanese online blogging communities. Lang. Commun. 2016, 48, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergriff, I. Emotive communication online: A contextual analysis of computer-mediated communication (CMC) cues. J. Pragmat. 2013, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampietro, A. Emoji and rapport management in Spanish WhatsApp chats. J. Pragmat. 2019, 143, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8039-5540-0. [Google Scholar]

- Skovholt, K.; Grønning, A.; Kankaanranta, A. The communicative functions of emoticons in workplace e-mails. J. Comput-Mediat. Comm. 2014, 19, 780–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G. Don’t take my word for it—Understanding Chinese speaking practices. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1998, 22, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E.; Fisher, L. A dialogic approach to promoting professional development: Understanding change in Hong Kong language teachers’ beliefs and practices. System 2022, 102901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phirangee, K.; Hewitt, J. Loving this dialogue!!!!: Expressing emotion through the strategic manipulation of limited non-verbal cues in online learning environments. In Emotions, Technology, and Learning; Tettegah, S.Y., McCreery, M.P., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2016; pp. 69–85. ISBN 978-0-12-800649-8. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Matthiessen, C.M.I.M. An Introduction to Functional Grammar, 3rd ed.; Arnold: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-340-76167-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, D.; Lee, C. “See you soon!” ADD OIL AR: Code-switching for face-work in edu-social Facebook groups. J. Pragmat. 2021, 184, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Discourse Function | Definition | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Positive evaluation | The writer agrees with or expresses appreciation for a previous message. | I do think your PPT files are nicely designed. (Minnie) |

| 2 | Negative evaluation | The writer disagrees with a previous post. | I am not sure if they could produce a poem individually. (Steve) |

| 3 | Making suggestions | The writer makes suggestions on how to improve teaching and learning. | I’d suggest you lead the whole class to read one to two paragraphs together. (Macy) |

| A. | Different types of downgraders that soften the impact a speaker’s utterance is likely to have on his interlocutor: |

| 1. | Politeness expressions Optional elements added to an utterance to show deference to the interlocutor and to make a bid for cooperative behavior, e.g., please. |

| 2. | Softeners Syntactical devices used to tone down the perlocutionary effect an utterance is likely to have on the addressee, e.g., a. Past tense: I wondered whether… b. Durative aspect markers: I was wondering… c. Negation: It might not be a good idea. d. Interrogative: Mightn’t it be a good idea? e. Modals: may, might, can, could, shall, etc. |

| 3. | Consultative devices Optional devices, mostly ritualised formulas, by means of which speakers seek to involve their interlocutor and solicit their cooperation, e.g., Would you mind if …, etc. |

| 4. | Hedges Adverbials (excluding sentence adverbials) by means of which a speaker avoids a precise propositional specification in order to circumvent the potential provocation such a specification might entail; the speaker affords his or her interlocutor the option of completing the utterance, thereby imposing his or her own intent less forcefully on the interlocutor, e.g., kind of, sort of, somehow, rather, etc. |

| 5. | Understaters Adverbial modifiers by means of which a speaker underrepresents the state of affairs denoted in the proposition, e.g., a little bit, not very much, etc. |

| 6. | Downtoners Sentence modifiers that modulate the impact of the speaker’s utterance, e.g., maybe, perhaps, probably, possibly, etc. |

| 7. | Committers Sentence modifiers that explicitly characterise the utterance as a personal remark and lessen the degree to which the speaker commits themselves to the propositional content of the utterance, e.g., In my opinion, I think, I guess, I believe, I suppose, etc. |

| 8. | Forewarning Linguistic structures that express a metacomment on a face-threatening act, e.g., This may be a bit boring to you, but…, etc. |

| 9. | Hesitators Pauses filled in with non-lexical phonetic material or instances of stuttering, e.g., erm, er, etc. |

| 10. | Scope-staters Elements in which the speaker explicitly expresses their subjective opinion, e.g., I’m not happy about the fact that you…, I’m afraid…, etc. |

| 11. | Agent avoiders Syntactic devices by means of which it is possible for the speaker not to mention themselves or their interlocutor as agents, thereby avoiding a direct attack, for instance, e.g., passive, impersonal constructions using they, one, etc. |

| B. | Different types of upgraders that strengthen the impact an utterance is likely to have on the addressee: |

| 12. | Overstaters Adverbial modifiers through which the speaker’s proposition is stated in an exaggerated manner, e.g., definitely, totally, of course, absolutely, etc. |

| 13. | Intensifiers Adverbial modifiers used by the speaker to intensify certain elements of the proposition made in their utterance, e.g., very, indeed, really, actually, do (auxiliary) |

| 14 | Committers Modifiers that help the speaker show their strong degree of commitment to a proposition, e.g., I’m sure, surely, certainly, etc. |

| C. | Other: |

| 15. | Emoticons Facial expressions pictorially represented by punctuation, letters or images to express the writer’s mood. They serve as upgraders for a positive evaluation and as downgraders for a negative evaluation or suggestion, e.g., I think there is room for improvement ☺. |

| Politeness Markers | Positive Evaluation | Negative Evaluation | Suggestions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | M | S | M | S | M | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | ||

| A. Downgraders | |||||||

| 1 | Politeness expressions | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | Play-downs | ||||||

| a. | Past tense | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| b. | Durative aspect markers | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 4.7 | 0.0 |

| c. | Negation | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| d. | Interrogative | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 5.7 |

| e. | Modals | 12.6 | 16.2 | 0.0 | 36.4 | 60.9 | 54.6 |

| 3 | Consultative devices | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 4 | Hedges | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 5 | Understaters | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 6 | Downtoners | 4.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 1.6 | 12.3 |

| 7 | Committers | 23.6 | 8.9 | 36.4 | 18.2 | 14.1 | 10.4 |

| 8 | Forewarning | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 |

| 9 | Hesitators | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 0.0 |

| 10 | Scope-staters | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| B. Upgraders | |||||||

| 11 | Agent avoiders | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 12 | Overstaters | 8.3 | 16.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 1.9 |

| 13 | Intensifiers | 41.7 | 37.5 | 0.0 | 9.1 | 9.4 | 6.6 |

| 14 | Committers | 1.4 | 10.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.8 |

| C. Other | |||||||

| 15 | Emoticons | 8.3 | 10.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 4.7 |

| Total * | 100.1 | 100.1 | 100.1 | 100.1 | 100 | 99.9 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chung, E.; Tang, E. Understanding Politeness in an Online Community of Practice for Chinese ESL Teachers: Implications for Sustainable Professional Development in the Digital Era. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811183

Chung E, Tang E. Understanding Politeness in an Online Community of Practice for Chinese ESL Teachers: Implications for Sustainable Professional Development in the Digital Era. Sustainability. 2022; 14(18):11183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811183

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, Edsoulla, and Eunice Tang. 2022. "Understanding Politeness in an Online Community of Practice for Chinese ESL Teachers: Implications for Sustainable Professional Development in the Digital Era" Sustainability 14, no. 18: 11183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811183

APA StyleChung, E., & Tang, E. (2022). Understanding Politeness in an Online Community of Practice for Chinese ESL Teachers: Implications for Sustainable Professional Development in the Digital Era. Sustainability, 14(18), 11183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811183