Abstract

There has been a gradual shift over the years towards the use of social networking sites (SNS) in formal and informal English language learning which was accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though there is an abundance of articles dedicated to probing into the in-depth use of SNS in English language learning, a clear correlation between the formal and informal application of SNS in English language learning is still scarce. Therefore, this systematic review aims to exhaustively analyse the recent findings regarding the integration of SNS in English language learning in both formal and informal learning contexts. Two databases were employed, which are the Web of Science (WoS) and Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC) and thirty articles were extracted for further review. These articles were selectively restricted to a five-year (2018–2022) range and have been screened for any contradiction against the research objectives. As an overview, SNS is favoured for different kinds of applications in teaching and learning purposes due to observed improvements in overall language skills, social interactions, motivation and flexibility. It is proposed for future researchers to focus on a specific target group as well as specific SNS platforms which could help the researchers to minimize discrepancies.

1. Introduction

Technology and learning evolution have always gone hand in hand. Incremental progress in one field most often triggers an equal reaction in the other. Ever since a decade ago, societies have witnessed a growth spurt in two of the most significantly intertwined subjects in the fields, social networking sites (SNS) and language education [1]. The numbers of SNS and their users, which have continued to grow steadily over the last ten years, have attracted the attention of educators, stakeholders and policymakers alike. The feasibility of incorporating SNS into the language learning process was studied involving numerous languages of choice such as indigenous languages [2], Spanish [3], Chinese [4], Japanese [5], German [5], Dutch [6] and most definitely English [7], as it is the lingua franca of the modern age.

SNS practicality in language learning is lacking scientific findings to support it [1]. Despite that, the majority of recent international studies have reported mostly positive outcomes on applying SNS to the current English language learning scheme and more so to be expected out of it in the foreseeable future. Both students and learners alike have largely benefitted from this application through the opportunities of acquiring limitless knowledge, borderless communications, interactive discussions and engagements, community support and natural language learning as a whole [3,8,9,10]. Hence, it is considered to acknowledge SNS as an educational tool to ameliorate the English language learning standards in Malaysia as well.

Malaysia being ranked eighth within the Asia and Pacific region for its Network Readiness Index (NRI) [11] makes it viable to revolutionize the current education system through the integration of SNS in English language learning. In fact, global researchers have already begun laying the foundation for this upcoming change through persistent research. Based on current findings, SNS undoubtedly aided English language learners to be positively affected in their language acquisition, motivation, confidence, and interest to engage in learning either formally or informally [8,10,12,13,14]. It has now become vital to ensure that SNS in English language learning could be sustained for generations to come in accordance with the Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) [15]. Hence, this systematic review is aimed at interpreting recent verdicts regarding the integration of SNS in English language learning to unearth the answers to the research questions as follows:

RQ1: What are the types of social networking sites (SNS) platforms used in both formal and informal English language learning?

RQ2: What are the impacts of social networking sites (SNS) on English language learning?

1.1. Formal and Informal English Language Learning

English language learning can be subdivided into two forms of learning processes, namely the formal and informal learning stages. Formal learning is a learning process defined by regulations and predetermined outcomes usually bounded by a physical class set-up, instructions, a fixed learning path and a specified timeframe [16]. On the other hand, informal learning itself is the embodiment of limitless learning in which the learning process is self-initiated, unrestricted by objectives and most notably takes place anywhere desired by the learner regardless of the topic of interest [16]. Over the years, educational institutions have been focusing more on standardizing the learning goals based on a fixated teacher-oriented performance assessment thus in a way renouncing the traditional notion of education which inspires informal learning through formal guidance [17].

Consequently, the shift in education standards has negatively affected learners’ interest and drive to indulge in formal learning any longer [18]. This phenomenon has prompted the majority of learners to direct their attention to informal English language learning which despite being unguided by professional entities, still offers quality content on par with what formal learning offers [16]. The rationale behind this transformation might be due to the fact that informal learning has effectually fulfilled the five distinct sources of support for language learning, particularly affective support, resource support, capacity support, technology support and lastly social support [18]. This presence is significantly pronounced through the widely used SNS among language learners.

1.2. SNS Integration in Formal and Informal English Language Learning

In order to comprehend the current situation of SNS-mediated learning in English language learning, it is noteworthy to entirely assess the benefits and confines of the SNS platform in both formal and informal English language learning settings. Among the interesting features of SNS in English language learning are the involvement of both learners and teachers in an interactive communication that takes place indefinitely [7], more opportunities to build collaborations with peers and professional individuals [19,20,21], easy access to information gathering [19,22], better awareness of language competency and acquisition based on the six pillars of English language (writing, speaking, reading, listening, vocabulary and grammar) [5,6,10,12,21,23,24] and likewise advocates for higher confidence and motivation in exchanging ideas [12,13,21,24]. However, SNS integration is also not entirely free of flaws as several studies have portrayed a number of unsettling issues of which some of which are that a percentage of English teachers are still sceptical about the assimilation of SNS into formal learning [7,25], concern for possible breach of security [20], lack of information credibility [20], insufficient training and guidance for implementation [25,26], sources of distraction [13,25], inadequate emphasis on subject accuracy in a formal context [5], accessibility of service (digital divide) [10,13] and certainly, any SNS community should have a substantial amount of competent language practitioners as its users to even impart a noticeably positive impact on the user base [27].

On a separate matter, certain common behaviours by learners towards the usage of SNS in informal learning specifically can also be observed based on the previous research. Learners prefer to isolate their informal learning environment from their teachers and they would not tolerate inefficient use of SNS in a formal setting just for the sake of complying with education standards [8,25].

2. Methods

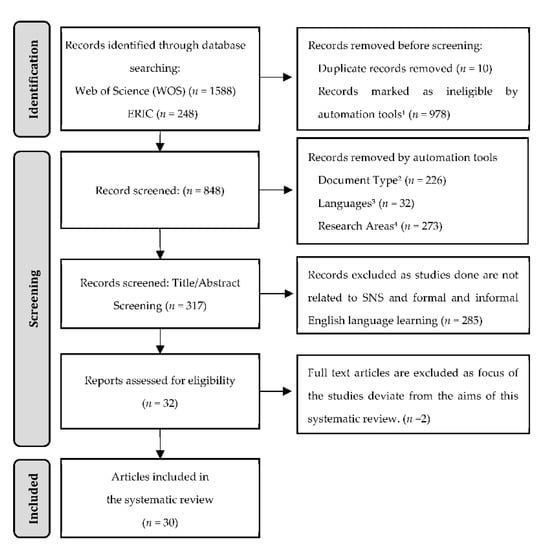

As indicated in Figure 1, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) is used as a framework and was adapted for the purpose of reporting this study. It is divided into four stages, known as identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion. Through the use of PRISMA, the findings of various studies are gathered and synthesized using systematic ways in order to answer the research questions. The following is the process for conducting a systematic review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA systematic review adapted from [28].¹ Records filtered by a range of publication years between 2018 and 2022.² Records filtered by document type other than journal articles (ERIC) and articles (WOS).³ Records filtered by languages whereby only English-language articles were chosen (WOS).⁴ Records filtered by research areas other than education educational research, linguistics and communication were excluded (WOS).

2.1. Identification

The initial process of this systematic review was centralized around database searching. The two relevant databases that were employed are the Web of Science (WoS) as well as the Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC). These two databases were restricted to a 5-year range (2018–2022) and a set of search strings was applied to each database that was generated precisely to suit the purpose of this study as depicted in Table 1 below. Both databases were selectively chosen for their comprehensive and trusted online library that have been indexing thousands of educational research articles. Most articles are peer-reviewed by field experts and can be sourced for free.

Table 1.

Search string used for WoS and ERIC.

2.2. Screening

Following the identification phase, the outcomes for both databases were evaluated in a screening phase. During the early stage of the screening phase, the researcher used the database automation tool to exclude ineligible publications such as books, book chapters, proceedings, non-peered reviews, non-English articles, journal articles as well as articles published before 2018. An extra filter was applied to WoS, where only three research fields of interest were selected: linguistics, communication and education educational research. This stage also involved the detection and removal of duplicated articles across both databases. As a result, a total number of 1480 ineligible articles were excluded in the first stage of the screening phase. A summary of the exclusion and inclusion criteria is summarized in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The next stage in the screening phase required the 287 articles to be screened based on their exactitude and accuracy to the focus of this systematic review which is related to the relationship between SNS, formal and informal learning as well as the English language. Article titles, abstracts as well as keywords of interest have been further analysed to shortlist the most relevant articles that suit the aforementioned criteria. This process ended up with a total of 32 numbers of articles suitable for the last stage of screening. Full-text articles were then excluded as the focus of some studies deviates from the aims of this systematic review.

2.3. Included

Thirty articles were shortlisted after going through a rigorous selection process via PRISMA. The findings of the selected articles are described in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

Summary of findings for each study.

The selected articles have met the criteria of this systematic review. These thirty articles revealed that there are five groups of targeted subjects that are of interest to researchers. A significant sum of studies was performed on the tertiary education level learners with 19 articles contributing to the list [30,31,35,36,38,39,40,43,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,58]. Five articles were directed towards the response from educators [33,34,42,56,57]. Meanwhile, the primary education level [29,47] secondary education level [37,44] and the general public [32,41] each have registered two articles investigating their feedback on SNS.

2.4. Data Analysis Procedure

The selected articles were transferred to Mendeley, a citation management application. The articles were analysed according to the main themes to address the research questions:

(1) What are the types of social networking sites (SNS) platforms used in both formal and informal English language learning?

(2) What are the impacts of social networking sites (SNS) on formal and informal English language learning?

To address the first research question, the SNS platforms were divided into two categories based on the articles’ main focus: formal and informal English language learning. The analysis regarding the second research question will provide the readers with a general overview of the benefits and challenges highlighted by all the articles according to the different types of SNS. The following section will discuss the findings of the articles.

3. Results

3.1. RQ 1: What Are the Types of Social Networking Sites (SNS) Platforms Used in Both Formal and Informal English Language Learning?

SNS are subdivided into Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Telegram, LINE, Twitter and YouTube, which was determined after reviewing all of the articles. Some articles utilized several types of SNS, whereas others did not specify the type of SNS they used in their study. This systematic study is intended to determine the frequency of SNS research done on both formal and informal English language learning, with the goal of determining whether SNS is preferred more in formal or informal English language learning situations as well as the platform that is favoured the most.

Based on Table 4 below, it can be deduced that Facebook has received the most attention as a single SNS platform to determine the efficacy of SNS in English language learning. Five articles [36,38,41,49,50] have researched the assimilation of Facebook in formal English learning whereas only one article [42] employed Facebook for informal English learning. About a third of the total articles reviewed [29,35,37,39,40,45,46,48,51,52,53,57] have not specified any SNS platform in the research, indicating that a lot of studies were done to investigate the influence of SNS as a whole on learning rather than just a single platform. Instagram may be regarded as the second most popular medium for informal learning, with two articles [43,47] devoted to the topic, but just one article [58] focused on its application in formal learning.

Table 4.

Types of SNS used in formal and informal English language learning.

In addition, WhatsApp [30,31] and Twitter [32,55] alike attracted less attention from researchers for their usage in informal learning with each one possessing only two articles highlighting its features. Telegram [34], LINE [54] and YouTube [44] are the platforms with the least number of articles documenting their versatility in either formal or informal learning. Only two articles integrated more than one platform into single research [33,56]. As a comparison between formal and informal learning, it can be deduced that researchers emphasized more on the relationship between SNS and informal learning [29,30,31,32,33,35,37,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] (23 articles) rather than considering SNS as integration in formal learning [34,36,38,41,49,50,58] (7 articles).

Additional findings that could be extracted from Table 3 are related to the frequency of SNS usage by English language learners which varies in each study. A total of eleven studies have highlighted the learners’ periodic access to SNS in their English language learning process. The most recorded time of SNS usage ranges between 0 and 5 h daily [29,45,47,51,52,53]. Several other studies measured SNS usage with no specifics of total login time but rather accepted the visiting frequency of SNS as a daily trend for these English learners [36,41,42,43] with an exception for one study which recorded SNS usage according to log-in hours per week with less than 5 h of SNS usage per week as the least while more than 20 h per week is the maximum amount of SNS usage [57].

It was also discovered that females actually tend to engage in more SNS-related activities though the basis for this claim is not strong with only three articles supporting it [45,46,51]. In fact, the opposite trend was exposed for English language learners in Yemen for which males recorded longer SNS usage than females due to customary beliefs [31].

3.2. RQ 2: What Are the Impacts of Social Networking Sites (SNS) on Formal and Informal English Language Learning?

To address RQ 2, the impacts of SNS are classified into two; benefits and challenges, which were found after reviewing the articles. The benefits were further categorized into five major themes: (1) Development of Language Skills, (2) Enjoyment and Motivation, (3) Facilitate Social Interaction, (4) Enhance Teaching and Learning Experience as well as (5) Flexibility. To sustain formal and informal language learning, the systematic review addressed the challenges raised in the articles: (1) Accessibility Issues, (2) Competency Problems, (3) Language Obstruction and (4) Negative Interaction, allowing them to be rectified sooner for future reference. Table 5 below summarizes the benefits and challenges of all the articles according to SNS platforms.

Table 5.

Impact of SNS on formal and informal English language learning.

Following this review of the articles, there are numerous advantages to be uncovered. The advantages must be addressed since they constitute the foundation for the SNS’s ongoing use in formal and informal English language learning. SNS has been shown to be effective in enhancing language skills including listening, speaking, reading, writing, grammar and vocabulary in 29 out of 30 articles [29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Out of these articles, the majority of them [32,33,36,37,39,40,41,42,45,46,47,49,50,51,55,56,57,58] recorded the language skills development as perceptions of participants engaging in activities like listening to interactive videos or voice notes, reading online contents either for vocabulary learning or entertainment, writing formal responses or texting their friends, exchanging voice recordings as well as calling their friends as part of speaking activities. Several other articles gathered their data by observing the participants’ level of English language proficiency as they participate in SNS-mediated activities which form the basis of their claims [29,31,34,38,43,44,48,52,53]. Only a handful of researchers have conducted actual tests to verify the extent of how the extensive use of SNS in learning has affected the participants’ English language skills development [30,54]. Looking into the usefulness of SNS platforms, Facebook as the most researched platform offers various accessible content such as videos and music of native English speakers [33]. Instagram exposes learners to the authentic use of English when interacting with global society [47]. Whatsapp and Telegram prioritized interpersonal relationships through the exchange of dialogues [56]. Other benefits that correlate to the usage of SNS are the facilitation of social interaction among participants and other users [30,31,32,33,36,38,39,41,42,43,44,45,47,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58] and the promotion of enjoyment and motivation in learning [36,42,43,45,46,47,48,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. It is apparent from these studies that the use of SNS has improved the teaching and learning experience [33,34,38,43,47,48,49,50,51,55,56]. Another intriguing feature of SNS is its flexibility in its application as highlighted by four articles [33,42,47,50].

Regarding the challenges in implementing SNS in formal and informal English language learning, competency issues appear to be the most significant challenge in adopting SNS, as evidenced by [31,33,36,49,51]. Students from lower socio-economic backgrounds where there is a lack of facilities, which might not favour SNS for their English language learning [31]. Teachers who received inadequate training in optimizing the educational use of Facebook in their teaching also have significantly lower competencies [49]. The next common issue that popped up in some studies [34,42] is the accessibility of SNS among the participants. Unequal opportunities in education that stem from unequal access to the Internet among students can also disrupt the teaching and learning process [34]. Language obstruction issues such as the use of coinages in formal writing that appeared in [35], as well as negative interaction in [32], are the least encountered issues in the overall review.

4. Discussion

4.1. Utilization of SNS Platforms in Formal and Informal English Language Learning

Since SNS is already an integral part of English language learners’ lives, SNS integration into formal and informal English language teaching and learning is highly feasible. To successfully execute the idea of including SNS in formal English language learning, teachers play an important part in this effort as they possess the expertise to properly implement the notion. With proper guidance and monitoring by the teachers, the existing features of SNS such as Instagram, Twitter and YouTube could be manipulated to improve the efficiency of lesson delivery, especially in the dissemination of learning resources [36]. The availability of supplementary resources on SNS which are readily accessible to the learners can support the ongoing learning processes provided by the teachers [50,51,55,57]. Young teachers are already technologically competent and entirely familiar with the social features of SNS which would ease the process of incorporating SNS into the formal teaching and learning of English [49]. Nevertheless, they would definitely need assistance in terms of adapting these features to the educational needs of the learners. The opposite is true for senior educators who are more familiar with the traditional teaching and learning system. They encountered difficulties in mediating their content through SNS which resulted in learners losing interest in pursuing formal English language learning through SNS [25]. It can be deduced that this technological gap between the younger and older generations has created a disagreement between them regarding SNS in English language teaching and learning [51]. The former highly appreciate the integration of SNS into their lives whether in learning or socializing while the latter are still indecisive about whether SNS will offer them the extra hand that they need.

Meanwhile, for informal English language learning, there is an equal interest in utilizing WhatsApp, Instagram and Twitter to supplement formal English language learning. It might be because such platforms have become an indispensable part of their lives and offer learners a real-life learning context [57]. This conforms to the feature of SNS in informal English language learning aforementioned earlier in Ref. [16]. As a matter of fact, these stand-alone platforms may encourage learners to pursue self-directed learning. Ref. [55] for instance, claimed that Twitter has benefitted the learners by increasing their dictionary skills as they search for new vocabularies to make their tweets more representable or to better explain their views. Considering Twitter is a platform where they are actively engaged with their peers, learners will surely make an effort to be presentable in public, thus, motivating them to do their best. Indirectly, they will develop communicative competency and better social interaction as a way to engage with other platform users [55].

4.2. Impacts of SNS on Formal and Informal English Language Learning

Multiple studies were dedicated to investigating the impact of overall SNS on formal and informal English language learning. The use of SNS in formal learning where fixated objectives, proper guidance, and constant monitoring are exercised in place by educators [51] is proven to be beneficial for English language skills development. The exact result of such practice could be observed from the previous articles that emphasized the integration of Facebook into formal English language learning [36,38,41,49,50]. All participants experienced the direct benefits of SNS on their learning progress whether in language skills or other complementing aptitudes [5,6,7,8,10,12,13,19,20,22,24]. Unfortunately, there also exists a negative consequence of using SNS in informal English language learning. Students tend to abbreviate or utilize acronymic phrases while chatting on social networking sites [35]. This is most probably due to the unguided use of SNS in informal English language learning which tends to leave the learners baffled by the actual purpose of the informal activity. Generally, it is fairly easy for learners to leisurely wander off into the simplified and unrestricted domain of SNS if left unattended which might also be a contributing factor to overlooking the formality and structure of language hence, the deterioration in language competency.

Another noteworthy feature of SNS in formal and informal English language learning is that it has offered learners a sense of motivation and pure enjoyment [12,13,21,24]. The source of motivation and positive behavioural change toward English language learning came from teachers’ and peers’ feedback [36,51], engagement with content that aligns with the learners’ interests [44,58], a supportive social community consisting of teachers, peers and other SNS users that encourages sustained English language learning [48,50], and meaningful interactions [38]. As students get better with their language proficiency, they shall also develop a better interest in continuing to learn English [46]. This is because learners have grown and improved self-confidence as a result of their extensive exposure to the nature of SNS, as mentioned in Refs. [19,20,21].

5. Limitations and Recommendations

There are certain limitations that came equipped with the results. The limitations are due to either independent variables concerning the participants and the existing environment, or the nature of the research methodology itself. In this particular case, both factors imposed a significant impact on the systematic review conducted.

As mentioned in several research articles before, there were mentions of the diverse educational and socio-economic backgrounds of the participants. It is clear that each participant possessed a different level of language proficiency prior to engaging in the research regardless of the research focus, leading to inconsistent outcomes as the heterogeneity of participants is unmanageable. Hence, the majority of studies have applied the generalization approach to obtain an intelligible result to be interpreted for real-life application. Likewise, the learning environment comprising of technology accessibility and exposure also played a huge role in influencing the participants’ reactions towards SNS. Naturally, the research on SNS was usually localized to a certain area or a target group in society in order to minimize the effect of the technological gap.

Referring to the current systematic review at hand, the methodology employed was more of a general approach to identify the role of SNS in both formal and informal English language learning communities. Two concurrent issues were identified during the review process, the first of which is the strict exclusion criteria that were dedicated to exploring all of the existing research articles resulting in only a humble interpretation of thirty shortlisted articles. Secondly, corresponding to the title of the review, the articles selected embraced a substantial part of society as well as the readily available SNS platforms. With no specific target group and SNS platform of choice, the review has generated only an overview of the association between SNS and English language learning within the formal and informal context serving as groundwork for future detailed studies.

Based on the review conducted, there are two suggestions that could be offered for future studies. It is deemed essential to specify the SNS platform(s) of interest as well as the target group to be researched at an early stage of the study in order to accumulate substantially better outcomes with valid and efficacious claims. This in fact is crucial to eliminate as many variables as possible especially those that are unmanageable in research to minimize any discrepancy in the results. Secondly, future research could employ focus on identifying the extent to which SNS could contribute to each formal and informal English language learning setting to then further compartmentalize the specific application of SNS to reap the best possible outcomes for both learning settings.

6. Conclusions

Summing up the systematic review, even though the research into the feasibility of SNS in supporting English language learning is progressing towards its maturity stage, it is still miles away from achieving a saturated pool of solutions to be able to construct solid guidelines for learners, educators, stakeholders and policymakers altogether. However, this systematic review did manage to furnish all the necessary findings on SNS implementation in formal and informal English language learning to assist with deciding the focus for future studies.

A general outlook on this review has established that SNS from a perspective is completely beneficial for both learners and educators. Improved language acquisition and efficacy, motivation to learn, social interaction and collaboration whether casually or professionally, confidence in practising language and even more in sharing and obtaining information, in general, are among the most common findings of previous studies. Nevertheless, it is compulsory to also recognize the prerequisites for such achievement to be sustainable. These prerequisites can only be deduced once the challenges of SNS in formal and informal English language learning have been analysed constructively and positively. These past studies have revealed that properly guided training, seamless network and technology accessibility, provision of creative content making and especially endless encouragement are among the most evident necessities to be fulfilled for the sake of sustaining the SNS-mediated language learning process.

Based on the thirty articles reviewed, there are risks associated with unguided use of SNS in informal English language learning related to listening, speaking, reading and writing skills. These crucial skills in English language learners depend on the competencies and experiences of English language educators in ensuring the credibility of the knowledge transfer. This quality is necessary for every informal language learning session through SNS in which participations of legitimate educators are usually limited. Clearly, this argument denotes that SNS is more suited to formal learning settings, particularly for English language skills development. However, it does not entirely dismiss the feasibility of SNS in informal English language learning wherein SNS is still preferred as a supplementary source for English language competency.

Even though English language learning primarily articulates around the four basic language skills, sustaining the learning process confides in the supporting factors such as motivation, interest and sense of belonging. The use of SNS in informal learning thrives on a social support system, full access to knowledge, self-discovery and unity which are undoubtedly scarce in a formal learning environment. These are essentially the rationale for learners’ dependability on SNS in informal English language learning. Accordingly, formal learning alone would not be able to mould a community enriched with English language appreciation without the assistance of informal learning. Both forms of language learning should exist in codependency to improve English language proficiency in society.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to several aspects of the study, specifically, conceptualization, F.N.Z. and M.M.Y.; methodology, M.M.Y.; validation, M.M.Y.; formal analysis, F.N.Z.; investigation, F.N.Z.; resources, M.M.Y.; data curation, F.N.Z. and M.M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, F.N.Z.; writing—review and editing, F.N.Z. and M.M.Y.; supervision, M.M.Y.; project administration, F.N.Z.; funding acquisition, M.M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia under research grant number GG-2020-024 and the APC was funded by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barrot, J.S. Scientific Mapping of Social Media in Education: A Decade of Exponential Growth. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2021, 59, 645–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.A.B. KeepOurLanguagesStrong: Indigenous Language Revitalization on Social Media during the Early COVID-19 Pandemic. Lang. Doc. Conserv. 2021, 2021, 239–266. [Google Scholar]

- Jerónimo, H.; Martin, A. Twitter as an Online Educational Community in the Spanish Literature Classroom. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2021, 54, 505–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C. The Influence of Extramural Access to Mainstream Culture Social Media on Ethnic Minority Students’ Motivation for Language Learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 50, 1929–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harting, A. L2 Engagements on Facebook: A Survey on the Network’s Usefulness for Voluntary German and Japanese Learning. EuroCALL Rev. 2020, 28, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheijen, L.; Spooren, W. The impact of WhatsApp on Dutch Youths’ School Writing and Spelling. J. Writ. Res. 2021, 13, 155–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, T.; Willis, J.; Lloyd, M. Evaluating Teacher and Learner Readiness to Use Facebook in an Australian Vocational Setting. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2019, 41, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; Rashid, R.A.; Nuby, M.H.M.; Alam, M.R. Learning English Informally through Educational Facebook pages. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2019, 7, 277–290. [Google Scholar]

- Yarker, M.B.; Mesquita, M.D.S. Using Social Media to Improve Peer Dialogue in an Online Course about Regional Climate Modeling. Int. J. Online Pedagogi. Course Des. 2018, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, T.M.; Yunus, M.M. Teachers’ Perception towards the Use of Quizizz in the Teaching and Learning of English: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, G.S.; Osorio, C.A.; Sachs, J.D. Network Readiness Index. 2021. Available online: https://networkreadinessindex.org/country/malaysia/ (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Chua, C.N.; Yunus, M.M.; Suliman, A. ICT: An Effective Platform to Promote Writing Skills among Chinese Primary School Pupils. Arab World Engl. J. 2019, 10, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.; Yunus, M.M. A Systematic Review of Social Media Integration to Teach Speaking. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, K.R.M.; Hashim, H.; Yunus, M.M. Sustainability Sustaining Education with Mobile Learning for English for Specific Purposes (ESP): A Systematic Review (2012–2021). Sustainability 2021, 13, 9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, W. Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. In A New Era in Global Health: Nursing and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Springer Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4 (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Sundqvist, P. Sweden and Informal Language Learning; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781119472384. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.S. International Journal of English Language, Literature and Translation Studies (IJELR) Developing Speaking Skills in ESL or EFL Settings Lecturer in English. Int. J. English Lang. Lit. Transl. Stud. 2018, 5, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık, T.; Balçıkanlı, C. EFL Teachers’ Autonomy Supportive Practices for out-of-Class Language Learning. IAFOR J. Educ. 2020, 8, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorghiu, G.; Iordache, D.D.; Pribeanu, C.; Lamanauskas, V. Educational Potential of Online Social Networks: Gender and Cross-Country Analysis. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2018, 76, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabaawi, M.Y.M.; Dahlan, H.M.; Shehzad, H.M.F. Social Media Usage for Informal Learning in Malaysia. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 2021, 17, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Yunus, M.M. A Systematic Review of Digital Storytelling in Improving Speaking Skills. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljekvist, Y.E.; Randahl, A.C.; van Bommel, J.; Olin-Scheller, C. Facebook for Professional Development: Pedagogical Content Knowledge in the Centre of Teachers’ Online Communities. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 65, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H.U.; Yunus, M.M.; Hashim, H. Language Learning Strategies Used by Adult Learners of Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL). TESOL Int. J. 2018, 13, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, C.K.; Kathiyaiah, D.; Hani, F.; Chanderan, V.; Yunus, M.M. “Myscene Tube”—A Web Channel to Enhance English Speaking Skills in an ESL Classroom. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 2021, 17, 1141–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueras-Maz, M.; Grandío-Pérez, M.D.M.; Mateus, J.C. Students’ Perceptions on Social Media Teaching Tools in Higher Education Settings. Commun. Soc. 2021, 34, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, N.; Soomro, K. Students’ Out-of-Class Web 2.0 Practices in Foreign Language Learning. J. Educ. Educ. Dev. 2019, 6, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, D.R. Online Informal Language Learning: Insights from a Korean Learning Community. Lang. Learn. Technol. 2018, 22, 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar]

- De Wilde, V.; Brysbaert, M.; Eyckmans, J. Learning English through Out-of-School Exposure. Which Levels of Language Proficiency Are Attained and Which Types of Input Are Important? Bilingualism 2019, 23, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherine, A.; Seshagiri, A.V.S.; Sastry, M.M. Impact of Whatsapp Interaction on Improving L2 Speaking Skills. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin-Hady, W.R.A.; Al-Tamimi, N.O.M. The Use of Technology in Informal English Language Learning: Evidence from Yemeni Undergraduate Students. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. Gulf Perspect. 2021, 17, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z.; Haidar, S. English Language Learning and Social Media: Schematic Learning on Kpop Stan Twitter. E-Learning Digit. Media 2020, 18, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.H.; Maor, D.; McConney, A. The Potential of Social Networking Sites for Continuing Professional Learning: Investigating the Experiences of Teachers with Limited Resources. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayzouri, A.H.; Mohebiamin, A.; Saberi, R.; Bagheri-Nia, H. English Language Professors’ Experiences in Using Social Media Network Telegram in Their Classes: A Critical Hermeneutic Study in the Context of Iran. Qual. Res. J. 2020, 21, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoera, O.S.; Aiwuyo, O.M.; Edemode, J.O.; Anyanwu, B.O. Impact of Social Media on the Writing Abilities of Ambrose Alli University Undergraduates in Ekpoma-Nigeria. GiST Educ. Learn. Res. J. 2018, 17, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizan, F.B.; Alam, M.Z. Facebook as a Formal Instructional Environment in Facilitating L2 Writing: Impacts and Challenges. Int. J. Lang. Educ. 2019, 3, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brevik, L.M. Gamers, Surfers, Social Media Users: Unpacking the Role of Interest in English. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2019, 35, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomenko, T.; Bilotserkovets, M.; Sbruieva, A.; Kovalenko, A.; Bagatska, O. Social Media Projects for Boosting Intercultural Communication by Means of Learning English. Rev. Amaz. Investig. 2021, 10, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamat, A.; Hassan, H.A. Use of Social Media for Informal Language Learning by Malaysian University Students. 3L Lang. Linguist. Lit. 2019, 25, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.S.; Shafie, N.H. English Informal Language Learning through Social Networking Sites among Malaysian University Students. Asian J. Univ. Educ. 2019, 15, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnamasari, A. Pre-Service EFL Teachers’ Perception of Using Facebook Group for Learning. J. English Teach. 2019, 5, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, M.; Shamsi, H. Exploring Learners’ Attitude toward Facebook as a Medium of Learners’ Engagement during COVID-19 Quarantine. Open Prax. 2021, 13, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonulal, T. The Use of Instagram as a Mobile-Assisted Language Learning Tool. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2019, 10, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-C.; Chen, C.W.-Y. Learning English from YouTubers: English L2 Learners’ Self-Regulated Language Learning on YouTube. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2020, 14, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, L.S.; Thang, S.M.; Noor, N.M. The Usage of Social Networking Sites for Informal Learning: A Comparative Study between Malaysia Students of Different Gender and Age Group. Int. J. Comput. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2018, 8, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, M.; Arisandy, F.E. The Impact of Online Use of English on Motivation to Learn. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2020, 33, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erarslan, A. Instagram as an Education Platform for EFL Learners. Turkish Online J. Educ. Technol.—TOJET 2019, 18, 54–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M.M.; Zakaria, S.; Suliman, A. The Potential Use of Social Media on Malaysian Primary Students to Improve Writing. Int. J. Educ. Pract. 2019, 7, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inpeng, S.; Nomnian, S. The Use of Facebook in a TEFL Program Based on the Tpack Framework. Learn J. Lang. Educ. Acquis. Res. Netw. 2020, 13, 369–393. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, Q.P.T.; Pham, T.N. Moving beyond Four Walls and Forming a Learning Community for Speaking Practice under the Auspices of Facebook. E-Learning Digit. Media 2022, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghazali, F. Utilizing Social Networking Sites for Reinforcing the Linguistic Competence of EFL Learners. Dil ve Dilbilimi Çalışmaları Derg. 2020, 16, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, P.B.; Yoshimura, S.M.; Doi, F. Intercultural Competence Development via Online Social Networking: The Japanese Students’ Experience with Internationalisation in U.S. Higher Education. Intercult. Educ. 2020, 31, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, A. Understanding the Characteristics of English Language Learners’ Out-of-Class Language Learning through Digital Practices. IAFOR J. Educ. Technol. Educ. 2020, 8, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P. Enhancing Online Language Learning Task Engagement through Social Interaction. Aust. J. Appl. Linguist. 2018, 1, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskiran, A.; Koral Gumusoglu, E.; Aydin, B. Fostering Foreign Language Learning with Twitter: Reflections from English Learners. Turkish Online J. Distance Educ. 2018, 19, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoshian, S.; Ketabi, S.; Tavakoli, M.; Koehler, T. Construction and Validation of Mobile Social Network Sites Utility Perceptions Inventory (MUPI) and Exploration of English as Foreign Language Teachers’ Perceptions of MSNSs for Language Teaching and Learning. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 2843–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmaz, O. Pre-Service Language Teachers’ Use of Social Networking Sites for Language Learning: A Quantitative Investigation. Eurasian J. Appl. Linguist. 2019, 5, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, F.M.; Wahyudin, A.Y. Undergraduate Students’ Perceptions toward Blended Learning through Instagram in English for Business Class. Int. J. Lang. Educ. 2019, 3, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).