Research on the Influence of Economic Development Quality on Regional Employment Quality: Evidence from the Provincial Panel Data in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Economic Development and Employment Quality

2.2. Regional Heterogeneity

2.3. Economic Growth

2.4. Sharing Economy

2.5. Economic Structure

3. Research Design

3.1. Comprehensive Evaluation Model Settings

3.2. Panel Regression Model Settings

3.3. Variable Selection

3.3.1. Explained Variable

3.3.2. Explanatory Variables

3.3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Data Sources

4. Empirical Results and Discussions

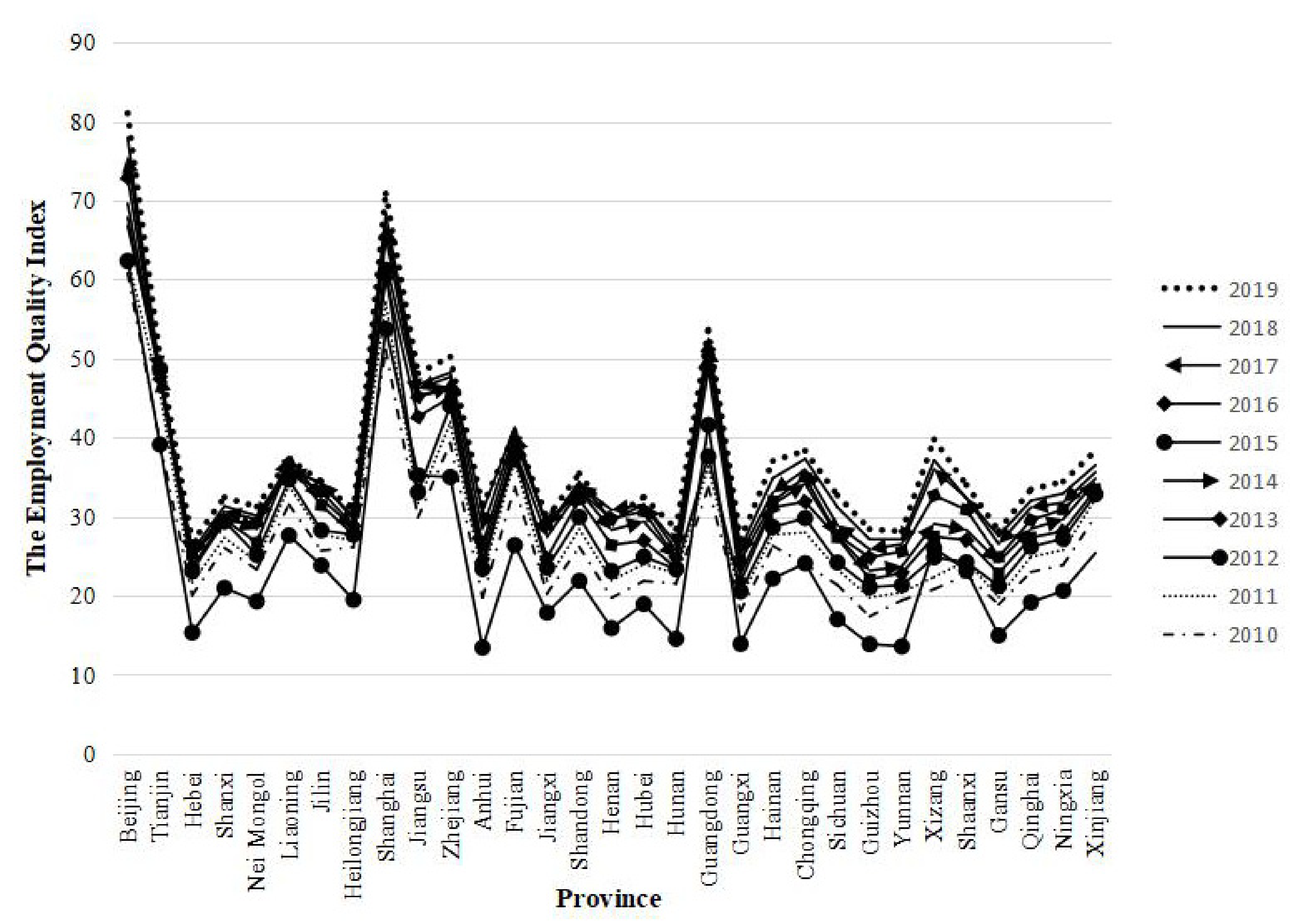

4.1. Employment Quality Index

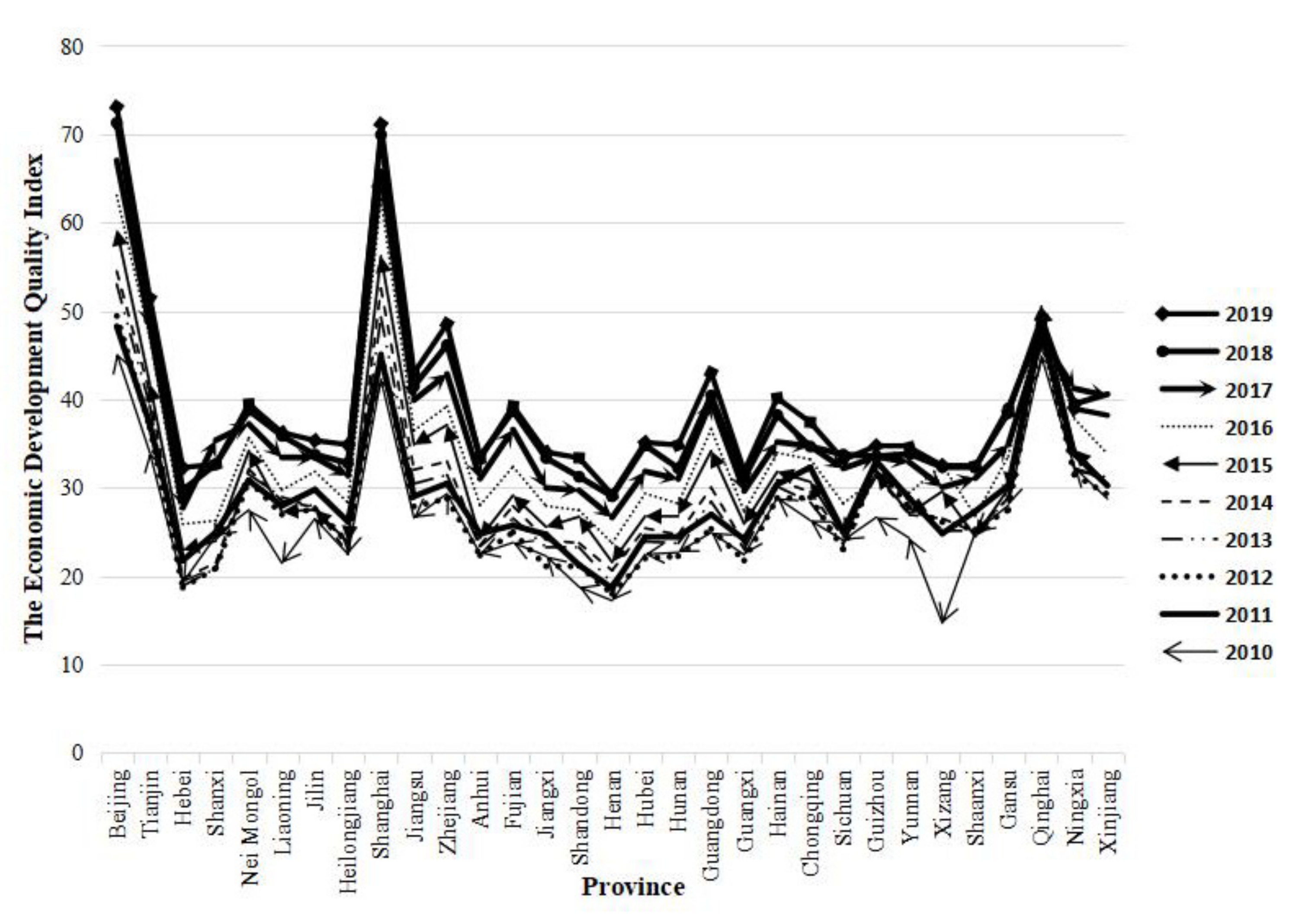

4.2. Economic Development Quality Index

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

4.4. Multicollinearity Test Results

4.5. Analysis of the Regression Results

4.5.1. Unit-Root Test and Cointegration Test

4.5.2. Analysis of the Model Regression Results

4.5.3. Influence of Different Dimensions on Employment Quality

4.5.4. Regional Heterogeneity

4.5.5. Robustness

- (1)

- Replace control variables

- (2)

- Change the regression model

- (3)

- Delete outlier data

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, H.; Yuan, X.F.; Li, P.G.; Liang, X.J. Stabilize employment, promote development and ensure people’s livelihood; local versions of the “14th five-year plan” for employment promotion released in succession. China Econ. Her. 2021, 12, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.W. Analysis of the relationship between economic development and employment of urban and rural labor forces in the 70 Years of New China. Soc. Sci. Yunnan 2019, 3, 34–40+186. [Google Scholar]

- Cazes, S.; Hijzen, A.; Saint-Martin, A. Measuring and assessing job quality: The OECD job quality framework. In OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hijzen, A.; Menyhert, B. Measuring labor market security and assessing its implications for individual well-being. In OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anker, R.; Chernyshev, I.; Egger, P.; Ritter, J. Measuring decent work with statistical indicators. Int. Labor Rev. 2003, 142, 147–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, P. Job quality in micro and small enterprises in Ghana: Field research results. In ILO Working Papers; International Labor Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, A.L.; Vaisey, S. Pathways to a good job: Perceived work quality among the machinists in North America. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 2005, 43, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H. The step and method to establishing the quantitative evaluation system on employment quality in China. Popul. Econ. 2005, 6, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Erhel, C.; Guergoat-Larivière, M. Job quality and labor market performance. In Centre for European Policy Studies Working Document; Université Paris1 Panthéon-Sorbonne: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, D.S.; Su, L.F.; Meng, D.H.; Li, C.A. Employment quality index of China’s province. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 2011, 11, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Deguilhem, T.; Frontenaud, A. Quality of Employment Regimes and Diversity of Emerging Countries; Cahiers Du Gretha (2007–2019); Groupe de Recherche en Economie Théorique et Appliquée (GREThA): Bordeaux, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, W.W.; Lian, Y.S.; Zhang, J.X. Employment quality evaluation and regional difference analysis for China’s labor force—Empirical analysis based on panel data of every province and city during 2005–2014. J. Harbin Univ. Commer. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 6, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- János, K. Progressive and Harmonious Growth; Economic Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, D.; Muller, L. Urban Competitiveness Assessment in Developing Country Urban Regions: The Road Forward; Paper Prepared for Urban Group, INFUD, the World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z.T.; Wang, T. Comprehensive appraisal system of economic quality. J. Harbin Univ. Commer. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2003, 19, 522–527. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, C.Z. Build the evaluation index system of economic development quality. Macroecon. Manag. 2008, 4, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zanakis, S.H.; Becerra-Fernandez, I. Competitiveness of nations: A knowledge discovery examination. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2005, 166, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.C.; Tan, M. The construction and empirical research of the economic development index system in Beijing. Commer. Times 2012, 2, 136–137. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.B. The economic development quality evaluation in Hebei Province. J. Hebei Univ. Econ. Trade 2013, 34, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.F.; Zhang, X.B. Coupling coordination and influencing factors between regional innovation capability and economic quality in Shandong Province. Resour. Dev. Mark. 2021, 37, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.D.; Wang, J. Regional economic development quality system, corporate social responsibility and financial competitiveness. Account. News 2021, 6, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.J.; Yao, Y.J. Study on the measurement of Beijing’s high-quality economic development. Res. Econ. Manag. 2021, 42, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, M.L.; Yin, T.T. High-quality Development Evaluation and the Measurement of Unbalanced of Provincial Economy in China. Rev. Ind. Econ. 2021, 5, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.F.; Yu, J.; Chen, Q.M. The impact of external shocks to the existence and nonlinearity of Okun’s law. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 2011, 8, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz, M.; Tang, C.F.; Shabbir, M.S. Electricity consumption and economic growth nexus in Portugal using cointegration and causality approaches. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 3529–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Xiong, J.; Cai, X. Analysis of the spatial impact of economic growth on the total amount and structure of regional employment. J. Commer. Econ. 2013, 12, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.W. Dynamic relationship between the employment and economic growth of county in China: Based on panel VAR model. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2015, 29, 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.C.; Zhang, Z.Y. Economic openness, financial development and employment structure evolution of western region. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2016, 5, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.D.; Li, F.; Wang, Q. Development Strategy of the Yangtze River Economic Belt and Employment: Promotion or Inhibition? A Difference-in-Differences Analysis Based on the Panel Data of Prefecture-level Cities. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2021, 30, 2569–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, M. Research on the spatial difference of the relationship between China’s economic growth and employment. Econ. Rev. J. 2022, 4, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, M.Q.; Yang, S.S. Research on the influence of technological innovation and industrial structure adjustment on employment. Econ. Trib. 2022, 4, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; Gong, X.S. The progress of science and technology, the upgrading of the industrial structure and regional employment differences: Based on the empirical studies by 31 provincial panel data in the four major economic zones of China. Ind. Econ. Res. 2012, 4, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z.S.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, H. Research on the employment dilemma and countermeasures of college students under the new normal of economic development. Jiangsu Commer. Forum 2021, 4, 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.B.; Fan, Q.X.; Zhou, X.Z.A. Coordination analysis of the coupling between employment structure and economic development in Sichuan and Chongqing region. China Econ. Trade Her. 2021, 17, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.B.; Zhou, H.L. Study on the influence of capital accumulation and economic growth on regional employment in China——Based on the interprovincial panel of 1993–2017. Sci. New Ground 2019, 19, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, S.C. Oken Model and Chinese Empirical (1978–2004). Stat. Decis. 2005, 24, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z. An empirical study on the relationship between economic growth and employment growth. Economist 2008, 2, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, K.H. Impact of total economic growth and structure on the employment of college graduates. Res. Financ. Econ. Issues 2016, 3, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.P.; Liu, C.X.; Liu, Q.C. Study on the effect of economic growth slowdown on individual income and employment. Ind. Econ. Rev. 2020, 11, 127–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, F.L. Research on the new employment model under the sharing economy model. Rev. Econ. Res. 2017, 62, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, R.S. Powerful society: Sociological interpretation of employment in the ara of sharing economy. J. Zhejiang Gongshang Univ. 2018, 6, 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.H. A study on the new employment pattern of sharing economy in China. J. China Inst. Ind. Relat. 2019, 33, 49–59, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.Y. An analysis of the impact of the sharing economy on employment. J. Brand Res. 2020, 25, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.M. The interaction mechanism of economic growth, economic structure and employment. Soc. Sci. Front. 2009, 4, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.J.; Liu, X. Foreign trade, economic structure and employment structure—An empirical analysis based on Guangdong data from 1979 to 2008. J. South China Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2010, 6, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, C.H.; Zheng, R.G.; Yu, D.F. An empirical study on the effects of industrial structure on economic growth and fluctuations in China. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 46, 4–16, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.W. Changes of China’s economic structure from the perspective of “dual circulation” development pattern. Shanghai Econ. Rev. 2021, 3, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.F. Research on the measurement and determination mechanism of employment quality in various regions during the transition period in China. Econ. Sci. 2013, 4, 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.H.; Li, S.L. A research on the employment quality of china: Based on the macro data from 2000 to 2012 of Liaoning. Popul. Econ. 2015, 6, 62–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Fan, Z.P.; Qin, Y.G. Construction and empirical measurement of high-quality economic development index system. Stat. Decis. 2022, 38, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.X.; Li, J.J. China’s OFDI reverse technology spillover, regional innovation performance and high-quality economic development: Analysis of simultaneous equations based on provincial panel data. J. Yunnan Univ. Financ. Econ. 2022, 38, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Xu, Z.Y.; Zhang, K.L. The impact of digital finance on the synergy of economic development and ecological environment. Mod. Financ. Econ. J. Tianjin Univ. Financ. Econ. 2022, 2, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.Q.; Meng, T.C.; Jiang, X. Study on the impact of intelligent manufacturing on labor employment quality structure and regional difference. Jianghan Acad. 2022, 41, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.Y.; Yang, Y. A study on the impact of intelligence development on employment structure. Ind. Technol. Econ. 2022, 41, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

| Target Layer | System Layer | Indicator Layer | Unit | Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Quality | Labor Wages | Average employee salary (WAGE) | Yuan | + |

| Wage growth rate (DWAGE) | % | + | ||

| Social Security | Social insurance ratio (INSURANCE) | % | + | |

| Ratio of the minimum wage to the average wage (MINWAGE) | % | + | ||

| Employment Structure | The proportion of the urban employed population (TOWN) | % | + | |

| The proportion of the employed population in the tertiary industry (THIRD-INDUSTRY) | % | + | ||

| The manufacturing employment rate (MANUFACTURE) | % | + | ||

| Work Availability | Labor participation rate (LABOR) | % | + | |

| Urban registered unemployment rate (UNEMP) | % | − |

| Target Layer | System Layer | Indicator Layer | Unit | Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Development Quality | Economic Growth | Gross regional product (GDP) | 108 Yuan | + |

| GDP per capita (RGDP) | Yuan/Person | + | ||

| Sharing Economy | Per capita disposable income (PCDI) | Yuan | + | |

| Consumer expenditure per capita (CPP) | Yuan | + | ||

| Economic Structure | Share of primary industry in GDP (FGDP) | % | − | |

| Share of the tertiary industry in GDP (SGDP) | % | + | ||

| Share of fiscal expenditure in GDP (MGDP) | % | + |

| Type | Variables | Specific Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Explained Variable | Employment Quality Index (EQI) | It is measured by the comprehensive calculation of the above evaluation index system of employment quality. |

| Explanatory Variables | Economic Development Quality Index (EDQI) | It is measured according to the comprehensive calculation of the above economic development quality index system. |

| Control Variables | Consumer Price Index (CPI) | It is measured by the natural logarithm of the consumer price index. |

| Urban–rural Gap (URG) | It is measured by the natural logarithm of the proportion of the urban population to the rural population. | |

| Education Expenditure (EE) | It is measured by the natural logarithm of the proportion of education expenditure in the total fiscal expenditure. |

| System Layer | Weight | Indicator Layer | Entropy Value | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labor Wages | 0.20 | WAGE | 0.96 | 0.16 |

| DWAGE | 0.99 | 0.04 | ||

| Social Security | 0.24 | INSURANCE | 0.95 | 0.19 |

| MINWAGE | 0.99 | 0.05 | ||

| Employment Structure | 0.42 | TOWN | 0.95 | 0.17 |

| THIRD-INDUSTRY | 0.98 | 0.08 | ||

| MANUFACTURE | 0.95 | 0.17 | ||

| Work Availability | 0.14 | LABOR | 0.98 | 0.07 |

| UNEMP | 0.98 | 0.07 |

| Regions | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 60.79 | 62.77 | 66.79 | 67.86 | 69.63 | 62.38 | 72.89 | 75.65 | 77.94 | 81.05 |

| Tianjin | 39.47 | 45.69 | 48.71 | 47.53 | 48.19 | 39.13 | 48.24 | 47.93 | 47.95 | 50.10 |

| Hebei | 20.06 | 21.70 | 23.13 | 23.67 | 25.06 | 15.35 | 25.23 | 25.08 | 25.65 | 26.76 |

| Shanxi | 26.06 | 27.35 | 29.41 | 29.62 | 30.07 | 20.99 | 29.33 | 30.66 | 31.33 | 32.46 |

| Nei Mongol | 23.32 | 24.28 | 25.18 | 26.77 | 28.42 | 19.30 | 29.29 | 29.68 | 30.11 | 31.27 |

| Liaoning | 31.53 | 33.86 | 34.71 | 36.75 | 37.44 | 27.64 | 35.64 | 35.85 | 36.34 | 37.29 |

| Jilin | 25.70 | 27.79 | 28.28 | 31.45 | 32.27 | 23.84 | 33.20 | 34.32 | 34.07 | 34.48 |

| Heilongjiang | 26.15 | 26.93 | 27.73 | 27.75 | 28.64 | 19.49 | 28.89 | 29.67 | 30.06 | 30.74 |

| Shanghai | 51.09 | 57.12 | 61.22 | 60.30 | 62.08 | 53.78 | 65.34 | 66.76 | 68.27 | 70.87 |

| Jiangsu | 29.89 | 31.73 | 33.10 | 42.65 | 45.28 | 35.25 | 45.22 | 46.17 | 46.71 | 48.14 |

| Zhejiang | 39.35 | 41.95 | 44.03 | 45.10 | 46.44 | 35.01 | 46.15 | 47.69 | 48.24 | 50.23 |

| Anhui | 19.78 | 22.47 | 23.40 | 24.50 | 25.50 | 13.43 | 26.50 | 28.47 | 30.74 | 31.33 |

| Fujian | 33.75 | 37.14 | 38.63 | 37.63 | 38.41 | 26.41 | 39.68 | 40.47 | 41.25 | 40.73 |

| Jiangxi | 20.28 | 21.92 | 23.55 | 24.80 | 27.44 | 17.85 | 28.94 | 28.91 | 28.60 | 29.84 |

| Shandong | 26.20 | 28.43 | 29.95 | 32.19 | 33.27 | 21.88 | 33.27 | 34.01 | 34.41 | 35.48 |

| Henan | 19.74 | 21.95 | 23.13 | 26.43 | 28.33 | 15.90 | 29.74 | 30.84 | 29.56 | 29.79 |

| Hubei | 21.87 | 24.00 | 24.94 | 26.97 | 29.38 | 18.95 | 30.68 | 31.52 | 31.53 | 32.48 |

| Hunan | 21.55 | 22.86 | 23.37 | 23.49 | 24.80 | 14.55 | 24.79 | 25.74 | 26.63 | 28.47 |

| Guangdong | 33.72 | 36.29 | 37.62 | 48.64 | 50.71 | 41.61 | 51.06 | 51.52 | 52.44 | 53.65 |

| Guangxi | 18.02 | 19.76 | 20.55 | 21.79 | 22.76 | 13.91 | 24.48 | 25.31 | 26.00 | 27.07 |

| Hainan | 26.32 | 27.72 | 28.69 | 31.19 | 31.56 | 22.18 | 31.94 | 33.04 | 34.88 | 37.06 |

| Chongqing | 23.99 | 28.00 | 29.83 | 31.90 | 34.16 | 24.11 | 35.01 | 35.97 | 37.31 | 38.34 |

| Sichuan | 21.37 | 23.35 | 24.22 | 27.38 | 27.57 | 17.02 | 27.67 | 28.94 | 31.21 | 32.71 |

| Guizhou | 17.38 | 19.79 | 21.08 | 22.10 | 23.18 | 13.88 | 24.84 | 25.89 | 27.14 | 28.42 |

| Yunnan | 19.42 | 20.42 | 21.35 | 22.85 | 23.71 | 13.59 | 25.61 | 26.55 | 27.14 | 28.15 |

| Xizang | 20.82 | 22.38 | 24.85 | 27.50 | 29.10 | 26.04 | 32.69 | 36.01 | 37.15 | 39.78 |

| Shaanxi | 22.64 | 24.43 | 24.24 | 27.04 | 28.34 | 23.19 | 30.88 | 32.38 | 32.34 | 34.03 |

| Gansu | 18.90 | 19.82 | 21.25 | 22.83 | 24.29 | 14.97 | 24.89 | 26.55 | 27.57 | 28.21 |

| Qinghai | 23.00 | 24.91 | 26.21 | 27.37 | 28.46 | 19.17 | 29.57 | 31.17 | 32.03 | 33.44 |

| Ningxia | 23.89 | 25.78 | 27.22 | 28.16 | 29.67 | 20.63 | 30.93 | 31.80 | 32.94 | 34.45 |

| Xinjiang | 30.07 | 32.24 | 32.84 | 33.44 | 34.45 | 25.40 | 34.80 | 35.63 | 36.52 | 38.34 |

| Year | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 37.91 | 34 | 12.45 | 26.8 | 81.1 |

| 2018 | 36.57 | 32.3 | 12.01 | 25.6 | 77.9 |

| 2017 | 35.81 | 31.8 | 11.78 | 25.1 | 75.6 |

| 2016 | 34.75 | 30.9 | 11.6 | 24.5 | 72.9 |

| 2015 | 34.41 | 30.2 | 11.71 | 13.4 | 62.4 |

| 2014 | 33.83 | 29.4 | 11.34 | 22.8 | 69.6 |

| 2013 | 32.51 | 27.8 | 11.21 | 21.8 | 67.9 |

| 2012 | 30.62 | 27.2 | 11.18 | 20.6 | 66.8 |

| 2011 | 29.18 | 25.8 | 10.46 | 19.8 | 62.8 |

| 2010 | 26.97 | 23.9 | 9.751 | 17.4 | 60.8 |

| System Layer | Weight | Indicator Layer | Weight | Entropy Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Growth | 0.25 | DGDP | 0.06 | 0.94 |

| RGDP | 0.20 | 0.96 | ||

| Sharing Economy | 0.40 | PCDI | 0.21 | 0.96 |

| CPP | 0.19 | 0.96 | ||

| Economic Structure | 0.35 | FGDP | 0.06 | 0.99 |

| SGDP | 0.14 | 0.97 | ||

| MGDP | 0.15 | 0.97 |

| Regions | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beijing | 45.18 | 48.24 | 49.41 | 52.98 | 54.46 | 59.21 | 63.03 | 67.00 | 71.27 | 73.07 |

| Tianjin | 33.97 | 37.20 | 36.77 | 39.26 | 40.70 | 41.73 | 46.97 | 48.32 | 48.97 | 51.45 |

| Hebei | 19.25 | 21.75 | 18.68 | 18.88 | 19.70 | 22.95 | 25.87 | 27.72 | 29.72 | 32.27 |

| Shanxi | 24.52 | 24.95 | 20.88 | 20.87 | 21.48 | 23.97 | 26.26 | 35.36 | 32.64 | 32.64 |

| Nei Mongol | 27.48 | 30.80 | 30.81 | 31.49 | 32.07 | 34.17 | 35.62 | 37.18 | 38.74 | 39.45 |

| Liaoning | 21.45 | 27.94 | 26.95 | 28.93 | 28.51 | 27.27 | 29.72 | 33.41 | 35.86 | 36.23 |

| Jilin | 26.49 | 29.77 | 27.57 | 27.83 | 27.78 | 27.49 | 31.8 | 33.40 | 33.73 | 35.32 |

| Heilongjiang | 22.47 | 26.15 | 23.80 | 23.32 | 22.51 | 23.83 | 28.31 | 31.35 | 32.77 | 34.85 |

| Shanghai | 42.23 | 44.79 | 45.07 | 49.26 | 52.53 | 56.18 | 62.63 | 65.76 | 69.92 | 71.12 |

| Jiangsu | 26.58 | 29.01 | 27.86 | 30.44 | 32.02 | 34.84 | 36.45 | 39.89 | 41.48 | 42.98 |

| Zhejiang | 29.31 | 30.46 | 28.75 | 31.43 | 32.95 | 37.09 | 39.19 | 42.84 | 46.14 | 48.51 |

| Anhui | 22.52 | 24.81 | 22.32 | 23.33 | 23.48 | 24.30 | 27.99 | 31.01 | 33.52 | 33.24 |

| Fujian | 23.78 | 25.73 | 24.95 | 26.51 | 27.91 | 29.11 | 32.37 | 36.56 | 38.66 | 39.21 |

| Jiangxi | 22.25 | 24.69 | 21.10 | 23.25 | 24.09 | 25.55 | 27.92 | 29.96 | 33.33 | 34.02 |

| Shandong | 18.75 | 21.24 | 21.16 | 23.23 | 23.71 | 26.71 | 27.44 | 29.68 | 31.22 | 33.36 |

| Henan | 17.21 | 18.61 | 17.97 | 19.18 | 20.62 | 21.56 | 23.72 | 26.62 | 29.01 | 29.22 |

| Hubei | 22.44 | 24.41 | 21.98 | 23.89 | 25.40 | 26.76 | 29.33 | 31.82 | 34.78 | 35.10 |

| Hunan | 22.66 | 24.44 | 22.24 | 23.70 | 24.67 | 26.92 | 28.19 | 30.97 | 32.20 | 34.81 |

| Guangdong | 24.93 | 26.95 | 25.32 | 28.39 | 29.99 | 34.15 | 36.61 | 39.74 | 40.42 | 42.99 |

| Guangxi | 22.39 | 24.15 | 21.74 | 23.06 | 23.68 | 25.90 | 27.28 | 29.61 | 31.07 | 31.84 |

| Hainan | 28.83 | 30.37 | 28.82 | 30.11 | 30.86 | 31.78 | 33.94 | 35.15 | 38.22 | 40.13 |

| Chongqing | 26.29 | 32.29 | 28.91 | 28.35 | 29.49 | 30.65 | 33.20 | 34.68 | 34.65 | 37.40 |

| Sichuan | 24.03 | 25.00 | 23.00 | 23.59 | 24.38 | 24.66 | 28.20 | 32.16 | 33.73 | 33.15 |

| Guizhou | 26.64 | 33.00 | 32.42 | 31.91 | 31.34 | 31.65 | 31.09 | 33.48 | 33.54 | 34.72 |

| Yunnan | 24.29 | 28.79 | 27.71 | 28.5 | 26.93 | 27.07 | 29.42 | 32.87 | 33.81 | 34.54 |

| Xizang | 14.66 | 24.81 | 26.08 | 25.11 | 26.50 | 29.57 | 32.55 | 30.05 | 32.32 | 32.49 |

| Shanxi | 24.94 | 27.32 | 25.26 | 24.96 | 24.96 | 24.44 | 26.78 | 31.07 | 32.26 | 32.45 |

| Gansu | 28.01 | 30.24 | 27.46 | 28.73 | 28.86 | 29.87 | 33.55 | 34.88 | 38.95 | 38.42 |

| Qinghai | 44.86 | 47.75 | 47.65 | 47.25 | 47.29 | 50.48 | 49.83 | 46.92 | 48.37 | 49.24 |

| Ningxia | 32.26 | 33.78 | 31.44 | 31.90 | 32.19 | 34.27 | 37.78 | 41.20 | 39.46 | 38.92 |

| Xinjiang | 28.73 | 30.22 | 29.23 | 31.18 | 30.78 | 30.35 | 33.81 | 40.37 | 40.57 | 38.18 |

| Year | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 39.40 | 35.32 | 10.04 | 29.22 | 73.07 |

| 2018 | 38.43 | 34.65 | 9.81 | 29.01 | 71.27 |

| 2017 | 36.81 | 33.48 | 9.32 | 26.62 | 67.00 |

| 2016 | 34.09 | 31.80 | 9.88 | 23.72 | 63.03 |

| 2015 | 31.43 | 29.11 | 9.06 | 21.56 | 59.21 |

| 2014 | 29.74 | 27.91 | 8.35 | 19.70 | 54.46 |

| 2013 | 29.06 | 35.21 | 8.06 | 18.88 | 52.98 |

| 2012 | 27.85 | 26.95 | 7.62 | 17.97 | 49.41 |

| 2011 | 29.34 | 27.94 | 6.94 | 18.61 | 48.24 |

| 2010 | 26.43 | 24.94 | 7.03 | 14.66 | 45.18 |

| Variables | N | Mean | Median | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQI | 310 | 32.26 | 29.39 | 11.96 | 13.43 | 81.05 |

| EDQI | 310 | 32.26 | 30.41 | 9.700 | 14.66 | 73.06 |

| CPI | 310 | 4.631 | 4.629 | 0.0120 | 4.611 | 4.666 |

| URG | 310 | 0.313 | 0.224 | 0.643 | −1.228 | 2.152 |

| EE | 310 | −2.933 | −3.002 | 0.349 | −3.521 | −1.693 |

| Variables | EQI | EDQI | CPI | URG | EE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQI | 1 | ||||

| EDQI | 0.772 *** | 1 | |||

| CPI | −0.0620 | −0.096 * | 1 | ||

| URG | 0.847 *** | 0.715 *** | −0.138 ** | 1 | |

| EE | −0.347 *** | −0.000 | −0.00900 | −0.541 *** | 1 |

| Variables | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| GUR | 5.210 | 0.192 |

| Economy | 3.620 | 0.276 |

| Edu | 2.530 | 0.396 |

| CPI | 1.040 | 0.963 |

| VIF mean | 3.100 |

| Statistic | EDQI | CPI | GUR | Edu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLC | −10.3253 *** | −12.9083 *** | −15.4224 *** | −6.1905 *** |

| p-Value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Smoothness | Data smooth | Data smooth | Data smooth | Data smooth |

| Cointegration Test | Specific Test | Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedroni | Modified Phillips-Perron t | 8.2808 | 0.0000 |

| Phillips-Perron t | −23.1290 | 0.0000 | |

| Augmented Dickey–Fuller t | −14.7554 | 0.0000 | |

| Westerlund | Variance ratio | 2.0940 | 0.0181 |

| Variables | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | Model (5) | Model (6) | Model (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQI | 0.616 *** (0.041) | 0.610 *** (0.043) | 0.435 *** (0.057) | 0.635 *** (0.043) | 0.416 *** (0.057) | 0.444 *** (0.056) | 0.427 *** (0.057) |

| CPI | −8.279 (18.289) | 41.549 ** (20.356) | 37.760 * (20.226) | ||||

| URG | 7.283 *** (1.651) | 9.237 *** (1.901) | 8.514 *** (1.701) | 10.224 *** (1.925) | |||

| EE | −3.295 (2.672) | −6.985 *** (2.667) | −6.610 ** (2.663) | ||||

| _cons | 12.388 *** (1.331) | 50.918 (85.126) | 15.938 *** (1.519) | 2.122 (8.431) | −176.472 * (94.282) | −5.224 (8.219) | −178.953 * (93.418) |

| N | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 |

| R2 | 0.451 | 0.451 | 0.487 | 0.454 | 0.494 | 0.499 | 0.505 |

| R2_a | 0.389 | 0.388 | 0.427 | 0.391 | 0.434 | 0.439 | 0.444 |

| Variables | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Growth | 0.316 *** | 0.243 *** | ||

| (0.035) | (0.081) | |||

| Sharing Economy | 0.214 *** | 0.078 | ||

| (0.027) | (0.066) | |||

| Economic Structure | 0.079 | −0.138 * | ||

| (0.074) | (0.079) | |||

| CPI | 32.718 * | 81.590 *** | 67.240 *** | 38.961 * |

| (19.473) | (19.830) | (22.221) | (22.555) | |

| URG | 8.177 *** | 7.290 *** | 18.497 *** | 8.564 *** |

| (1.884) | (2.107) | (1.996) | (2.090) | |

| EE | −0.594 | −4.781 * | −6.419 ** | 0.670 |

| (2.604) | (2.623) | (3.137) | (2.884) | |

| _cons | −133.753 | −368.798 *** | −306.268 *** | −154.799 |

| (90.369) | (91.921) | (104.114) | (105.450) | |

| N | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 |

| R2 | 0.542 | 0.518 | 0.407 | 0.548 |

| R2_a | 0.486 | 0.458 | 0.334 | 0.488 |

| Variables | Central Region | Western Region | Eastern Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDQI | 0.244 (0.207) | 0.237 * (0.136) | 0.536 *** (0.082) |

| CPI | 55.388 (43.297) | 66.120 ** (30.840) | 25.337 (38.547) |

| URG | 13.369 ** (6.098) | 16.601 *** (3.118) | 1.900 (4.220) |

| EE | −10.491 * (5.365) | −8.389 ** (3.580) | 1.431 (5.118) |

| _cons | −269.799 (196.42) | −307.909 ** (139.862) | −91.787 (181.268) |

| N | 80.000 | 120.000 | 110.000 |

| R2 | 0.453 | 0.599 | 0.501 |

| R2_a | 0.365 | 0.541 | 0.427 |

| Variables | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | Model (5) | Model (6) | Model (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDQI | 0.606 *** (0.041) | 0.605 *** (0.044) | 0.467 *** (0.059) | 0.629 *** (0.044) | 0.453 *** (0.059) | 0.475 *** (0.058) | 0.463 *** (0.063) |

| CPI | −1.481 (19.277) | 35.916 * (21.368) | 52.743 * (28.092) | ||||

| URG | 5.811 *** (1.776) | 7.415 *** (2.011) | 7.060 *** (1.823) | 10.452 *** (1.147) | |||

| EE | −4.391 (2.833) | −7.347 ** (2.860) | −1.482 (1.471) | ||||

| _cons | 13.179 *** (1.343) | 20.068 (89.693) | 15.397 *** (1.482) | −0.720 (9.067) | −151.085 (99.060) | −7.383 (8.990) | −234.543 * (129.50) |

| N | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 |

| R2 | 0.457 | 0.457 | 0.480 | 0.463 | 0.486 | 0.493 | 0.778 |

| R2_a | 0.397 | 0.394 | 0.419 | 0.400 | 0.424 | 0.432 | 0.775 |

| Variables | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | Model (5) | Model (6) | Model (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDQI | 0.952 *** (0.045) | 0.953 *** (0.045) | 0.421 *** (0.048) | 0.952 *** (0.037) | 0.421 *** (0.048) | 0.474 *** (0.063) | 0.462 *** (0.059) |

| CPI | 13.151 (37.196) | 56.563 ** (27.836) | 31.328 (21.244) | ||||

| URG | 11.205 *** (0.721) | 11.351 *** (0.721) | 10.093 *** (1.135) | 8.396 *** (2.031) | |||

| EE | −11.907 *** (1.040) | −1.855 (1.463) | −6.972 ** (2.865) | ||||

| _cons | 1.551 (1.503) | −59.401 (172.398) | 15.165 *** (1.427) | −33.375 *** (3.302) | −246.811 * (128.932) | 8.373 (5.544) | −151.438 (98.096) |

| N | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 310.000 | 280.000 |

| R2 | 0.596 | 0.597 | 0.774 | 0.717 | 0.777 | 0.775 | 0.498 |

| R2_a | 0.595 | 0.594 | 0.773 | 0.715 | 0.775 | 0.773 | 0.435 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Shao, J. Research on the Influence of Economic Development Quality on Regional Employment Quality: Evidence from the Provincial Panel Data in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710760

Wang Q, Shao J. Research on the Influence of Economic Development Quality on Regional Employment Quality: Evidence from the Provincial Panel Data in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710760

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qiong, and Jiahui Shao. 2022. "Research on the Influence of Economic Development Quality on Regional Employment Quality: Evidence from the Provincial Panel Data in China" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710760

APA StyleWang, Q., & Shao, J. (2022). Research on the Influence of Economic Development Quality on Regional Employment Quality: Evidence from the Provincial Panel Data in China. Sustainability, 14(17), 10760. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710760