Abstract

Environmental and Sustainability Education (ESE) in the formal sector is evolving rapidly across global contexts. Early Childhood settings are increasingly being seen as fertile grounds for promoting ESE values, attitudes and life-long pro-environmental behaviours. This article provides an in-depth understanding of the Early Childhood policy frameworks in India, China and Japan, focusing on how these support ESE implementation in Early Childhood settings. The study provides a comparative analysis of the key commonalities in the policy frameworks, the main enablers and vital challenges. It also offers a deep conversation on the convergences and divergences that bring together these three Asian countries in their goals of ESE implementation. Finally, the paper appeals to a global audience by offering a review of non-dominant approaches in these three countries, drawing upon their distinctive social, cultural and political contexts. The paper showcases the commonalities and divergences in Eastern cultures and also provides a lens to decipher key shifts from dominant Western philosophies. Overall, the paper responds to the call of this special issue to look at alternative perspectives and understand ESE in different contexts.

1. Introduction

Environmental and Sustainability Education (ESE) is slowly gaining momentum due to the increasing environmental issues and the urgency to help resolve them. Education in many ways offers an opportunity as a driving force for bringing about change [1]. The ongoing pandemic has in many ways reinforced the needs for caring for our planet, and ensuring ESE is a key parameter across all education parameters, especially ECE. The concept of sustainability continues to be complex and is still fluid with many versions. One particular version of sustainability that speaks to the authors has been provided by Davis [2], in which she positions sustainability as an issue of social justice and fairness that disproportionately impacts poorer people and whose effects will be felt much more strongly by the future generations, namely our children and grandchildren.

There is a need for varied lenses in creating better understandings of this sustainability [3]. Sustainability also has many dimensions such as space, time, history, ethics and culture. How sustainability is understood therefore ‘differs from country to country, culture to culture, develop over time and are based on varying sets of norms and values’ [3] (p. 9). Current understandings on how environment and sustainability tend to be heavily influenced by predominantly Western perspectives [4]. While ESE is critical at all stages and in all sectors, its role in Early Childhood Education (ECE) has yet to gain wider recognition. ECE provides immense opportunities to lead children into ‘interest, knowledge and values that will give support for a more sustainable world’, as it capitalises on children’s innate curiosity and ability to connect to the natural world [5] (p. 369). The social, economic, health and educational benefits of ECESE (Early Childhood Environment and Sustainability Education) have proven to be immense with great value in building children’s capabilities as young active citizens [6].

There have been regular calls for transformative learning that goes beyond ‘nature play’ [7] and supports the development of active citizens that understand sustainability at deeper levels [8]. Place-based education that takes into consideration local perspectives is critical towards supporting these initiatives. In Green’s [9] (p. 164) words, ‘children’s sustainability knowledge is produced from diverse and multiple relational interactions … through sensorial, experiential, open-ended and place-based ways of learning’. Educators are seen as agents of change that are responsible for ushering the reforms needed for impactful ECESE [8]. Campbell and Speldewinde’s [10] research further emphasizes the role of educators in promoting ECESE whereby when provided with the right opportunities by their teachers, young children develop a deep understanding of a range of key elements of sustainability.

Critical inspection of the impact of international development on how children and families are seen in non-Western perspectives is important [11]. An earlier study offered a good comparative analysis of key concepts in a few of the more economically developed nations [12]. It is timely to look into alternative perspectives and what they have to offer in terms of complementary conceptions of environment and sustainability.

The main objectives of this article are:

- To analyse environmental and sustainability education concepts in early childhood curriculum policy in India, China and Japan.

- To provide a comparative analysis of these key ESE concepts between these three nations as well as with Western notions.

- The key Research Questions:

- How are environmental and sustainability education concepts embedded (present) in early childhood curriculum documents in India, China and Japan?

- What are the similarities and differences among these perceptions, and how do they compare to existing Western notions of ESE?

Significance of This Study

This study is an attempt to provide a glimpse into those windows. We offer a comparative analysis of key concepts and understandings of environment and sustainability enacted through key policy documents in India, China and Japan. We also weave in the differing operating cultural paradigms and discourses that at times appear to converge and at other times diverge. It showcases alternate concepts of ESE and how these might be used to advance the entire global discourse of ESE. This is highly significant given the paucity of research that offers similar comments and critical insights into ECE curriculum in three major Eastern countries. India, China and Japan were chosen due to the pre-exiting opportunities for collaboration. The comparison also supports the key research aims to address significant knowledge gaps in understanding policies and practices. This brings out the richness of the various understandings, as well as the fertile options available to the global audience when navigating ESE.

2. ESE in EC Settings: Overview of ECE in India, China and Japan

ECE education system and pedagogy were basically first imported from the West in the 19th century; therefore the basics of ECE in three countries have been influenced by Western pedagogies, although each country has developed to infuse its own pedagogy from cultural perspectives [12]. We, the authors, had robust discussions on what key concepts of ESE in Early Childhood settings stand out in our contexts. These conversations offered ideas for comparison across different curriculum settings and helped us narrow our focus concepts to the following:

Environment, sustainability, nature, critical thinking, agency, voice, children as participants and children’s rights and care. The following section will provide a deeper understanding of the uptake of these concepts.

Table 1 shows the policy documents, role of the government and centres, role of the teacher and the view of children described in the policy documents in the three nations.

Table 1.

Overview of the policy documents, roles of the governments and centres, and the view of teachers and children.

2.1. Indian Setting

India has a diffused education system. There is a national education curriculum, and the central government suggests policies and programmes for the entire country. However, each state is responsible for managing how the central mandates are adopted within the state, thereby allowing for flexibility based on context. This is important because India is a hugely diverse country with nearly 1652 languages and many more dialects (REF). The National Council for Educational Research and Training (NCERT) is a national organisation that plays a key role in developing policies and programmes, which are adapted by the State Council for Educational Research and Training (SCERT). However, each state has reasonable freedom in implementing these within their education system. The recently released National Education Policy [17] recognises Early Childhood Education within the formal sector for the first time. The NECCECF [16] provides a clearer picture of the role of teachers in the system.

The National Council of Teacher Education (NCTE) plans and coordinates all teacher education in India including EC or pre-primary levels. The NECCECF [16] recognises ECE and qualifications of teachers as a highly neglected issue that needs stronger governance and quality control. At the moment, accreditation as an EC educator is through a Diploma in Education or a Bachelor’s degree in Education. There are numerous providers, both private and public, that provide these educational options with varying levels of theory, practice and experiences. There are no central government qualifying examinations nor any centrally mandated ongoing professional development programs, which often present an issue of quality control. This all leads to EC teachers who are under-prepared or inadequately prepared with courses that are obsolete and devoid of practical hands-on training [16].

The NECCECF [16] provides a clear understanding of the role of the teacher as a guide and facilitator, determining it as the single most important (and yet most neglected) factor when it comes to quality of ECE. Traditionally, teachers are respected as ‘guru’, someone who leads from darkness to light, the provider of wisdom and skills. While EC teachers are provided some nominal respect, this high status is generally reserved for teachers of higher grades. EC teaching is seen as an ‘easy job’ that anyone can do and does not require many skills or much professional learning. The ambiguity in qualification standards further lends credence to this bias. The NECCECF [16] recognises the need for standardised improved and ongoing professional development opportunities for EC teachers, a stronger curriculum and closer connections to community. It calls for teachers to enjoy being with children, to be knowledgeable about child development and to possess requisite skills to implement ECE programmes. The role of the teacher is well articulated in this policy document, with clear indicators of expectations and requirements all geared towards all-round development of children [16] (p. 62).

2.2. Chinese Setting

In China, a centralised country, all important educational decisions are made centrally. In the meantime, the provincial and municipal governments have the autonomy to issue rules and regulations on ECEC suitable to their own conditions and resources within the framework of educational law and policies issued by the central government.

According to Professional Standards for Kindergarten Teachers [21], kindergarten teachers should have professional ethics, professional knowledge and professional skills which require them to have received professional education and training before and during their service. To be a kindergarten teacher, one must take local exams to obtain a teacher certificate and the basic requirement is that she/he has completed tertiary education. The guidelines have made it clear that kindergarten teachers should shoulder different responsibilities in their daily work. First, they should be teachers who help the children build a solid foundation for their subsequent school learning and their lifelong development and education. They should be a leader to lead the children to carry out different activities. At the same time, they should be providers when children need any support, materially or psychologically. Teachers are also facilitators who facilitate different activities among children and communications with parents.

2.3. Japanese Setting

Japan has a long history of national guidelines (curriculum) since the end of the 19th century [22]. Certificates are also national licences. The national guidelines influence not only education provided by early childhood centres, but also the curriculum of teacher education in universities (four years), in other teacher training schools (two years) and in teachers’ professional development. However, the local government (usually municipalities governments) has responsibility for the management of early childhood services. In Japan, services for early childhood education are run by both public and private sectors. Public centres are governed by the municipal governments; therefore their practices are directly influenced by the national guidelines. However, for private centres, it is difficult to introduce the philosophy of the national guidelines. For example, the national guidelines do not recommend teacher-centred teaching. However, some private centres engage in teacher-centred teaching for reading, writing and mathematics. In Japan, in the revision of the national curriculum in 1989, it was confirmed that early childhood education is child-centred, and education is through the children’s (learning) environment. In this scheme, a teacher’s role is as creator of the learning environment and supporter for children to produce independent play in their ordinary lives. Some 30 years have already passed since this revision, and this philosophy has penetrated, especially in public sectors. Other than these, a teacher is expected to care about children like a parent, to behave as model human beings, to maintain documentation and to support families. Nowadays, early childhood teachers have various roles.

3. Theoretical, Conceptual and Analytical Frameworks

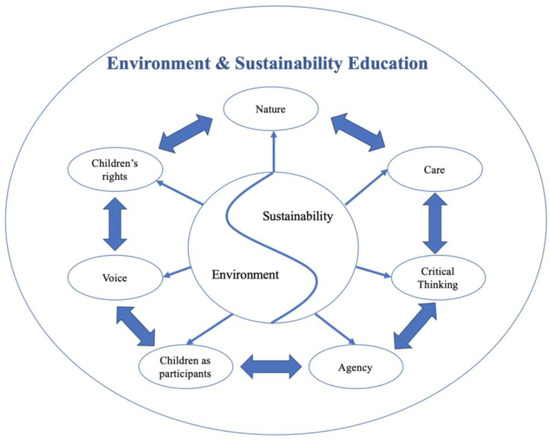

To generate a systematic analysis, we started by analysing some key initial ESE concepts and quickly found a broader usage of other terms in the curriculum. Figure 1 below illustrates the concepts we have utilised for analysis followed by their definitions, which we have adopted for analytical purposes. In Figure 1, we position ESE as containing two main concepts—Environment and Sustainability. We see these two concepts like two sides of a coin in which no one side is more important than the other. The sub-concepts that emerge from this central star illuminate the field.

Figure 1.

The terms for analysis—the ESE star.

Environment is a widely used term with a broad range of definitions and meanings. According to the dictionary definitions, it can cover ‘nature’, for example, the air, water, minerals, organisms and all other external factors surrounding and affecting a given organism at any time. It can also be the aggregate of surrounding things: conditions, or influences; surroundings and milieu. It can also be the social and cultural forces that shape the life of a person or a population. Additionally, it can mean an indoor or outdoor setting that is characterised by the presence of environmental art that is itself designed to be site-specific.

Sustainability The complexity of sustainability has often been dissected into three dimensions: ecological, economic and social/cultural [23] (p.375). Davis [2] positions sustainability as something that goes beyond simply addressing concerns with the natural environment. According to her, ‘sustainability emphasises the linkages and interdependencies of the social, political, environmental and economic dimensions of human capabilities. It ‘acknowledges relationships between humans and between human and other species, is underpinned by critique of the ways in which humans’ use and share resources and recognises intergenerational equity issues’ [2] (p. 3).

Nature here refers to natural landscapes and places and green areas of uncultivated land, which may be shaped by human activities, but the elements of earth, air, water, growing things and wildlife exist independently of human intervention. This also includes parks and urban areas [24] and covers the local environments used by the children [24].

Critical thinking is an attitude of being disposed to consider in a thoughtful way the problems and subjects that come within the range of one’s experience, knowledge of the methods of logical enquiry and reasoning and some skill in applying those methods [25].

Agency means the capacity, condition or state of acting or of exerting power; an agent is a person or thing through which power is exerted or an end is achieved.

Voice generally means sound produced by vibrations by means of lungs, larynx or syrinx, especially sounds produced by human beings, but it also means an instrument or medium of expression.

Children as participants means children who take part in or become involved in a particular activity.

Children’s rights according to UNICEF [26], children and young people have the same general human rights as adults and also specific rights that recognise their special needs. Children are neither the property of their parents nor are they helpless objects of charity. They are human beings and are the subject of their own rights. The Convention on the Rights of the Child sets out the rights that must be realised for children to develop to their full potential.

Care means the process of protecting someone or something and providing what that person or thing needs.

3.1. Methodology for Comparative Analysis

Precursors to the study were chance encounters and conversations between the three researchers. Two of us had met at the Transnational Dialogue 4 (TND4) symposium in Victoria, Canada. Engaging in the workshops and conversations with a range of international participants, we were made conscious of the richness in bringing together different perspectives on ESE, especially in early childhood settings. Another chance meeting in China with the third participant led to similar thoughts of how ESE is viewed differently across countries. These conversations led to a consensus on the need for a comparative study of ESE across cultures, traditions and society.

Our aim is to put together a long-term collaborative study that showcases how ESE is understood, negotiated, determined and implemented in different contexts. This article is a first step in this direction and starts at what we see as the beginning of this research agenda. We aim to analyse how key concepts of ESE are described in different Asian nations. The key concepts were first discussed in line with Weldermariam et al.’s [12] article that highlighted these concepts.

3.2. Dialogical Analysis

The dialogic aspect of the analysis process means where we, the three researchers, were in dialogue with each other. One key aspect of the dialogue was identifying what came across as key concepts [12] in our individual contexts. The authors are able to provide insiders’ views [27] of their own cultures after independently analysing the data. In the meantime, as outsiders of the other two cultures, we could then recognise aspects that the insiders might not see [27], which contributed to the dynamic and interactive dialogues and allowed for deeper thinking and comparison. This process included regular weekly Zoom meetings with the authors for over five months discussing ideas, churning through key terms and comparing different perspectives, as well as attempting to jointly write up the analysis of key concepts. A major enabler supporting this study has been technology with the COVID-19 pandemic providing increased confidence in using Zoom, shared drives and documents.

Table A1 in Appendix A provides a snapshot of the conversations that led to the analysis of the concepts that we as authors and researchers see as important to our respective national contexts. This, though, leaves it open to researcher bias and individual interpretations; it is agreed that the number of mentions of the term counts is the number of the appearances of the terms in the analysed documents.

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. India

Analysis of the recently released National Early Childhood Care and Education Curriculum Framework [28] shows that the term ‘environment’ is prominent and mentioned 25 times in this key policy document. It shows a common reference to the term as a physical space which needs to be decorated, which can be observed for patterns, colours and shapes and where one can celebrate festivals. The environment is our surroundings, including one mention of the plants/animals and the need to prevent pollution. However, a more holistic understanding that goes beyond the environment as a ‘resource’ and promotes engagement with the everyday environment is absent. Sustainability has zero references in the new curriculum. This term is missing completely despite the fact that India is a major signatory to key international documents that promote sustainability, has robustly participated in the development of the Sustainable Development Goals and is seen as actively aiming to achieve these. The question to ask is how this can be achieved if the term ‘sustainability’ is missing from its key document that shapes education of future generations.

The curriculum promotes nature as something out there to be admired for its colour, pattern and beauty rather than something that is part of young children’s everyday lives. The ambiguity of the term ‘nature’ means that how children perceive ‘nature’ can be heavily reliant on how children understand this term and their lived experiences. It also means that children do not see their everyday life experiences as linked to ‘nature’ which does not then include their outdoor play spaces, local green spaces or even windowsill gardens. Sobel [29] promotes ecophilia as a means to promote environmental consciousness and values. In order to do this, he highlights the need to incorporate ‘nature’ learning experiences in the curriculum.

This flows on to the lack of connection with ‘care’ (mentioned 38 times) towards the environment, everyday ‘nature’ or the planet. This leads to a dichotomy in how we understand ‘nature’ as something out there in the distance rather than something that is part of our daily milieus.

Interesting concepts of critical thinking, voice, agency, children as participants and children’s rights elicit no mention in this curriculum document. There is one mention in the entire document of the term ‘responsibility’ as something that caregivers and teachers are expected to create ‘opportunities for taking responsibility’ on [28], p. 41. It still does not stem from what children can actively do but is projected as something the educators/caregivers may aspire to provide. The latest National Education Policy [16] provides two mentions of environment specifying what it entails, including climate change, but limits this to Higher Education Institutions, thereby losing an opportunity to strongly embed ESE within the entire policy and more specifically in ECE.

4.2. China

The term ‘environment’ is mentioned 25 times in total in the national guidelines for kindergarten curriculum development. It has been referred to as the ‘natural environment’ which one needs to get to know and protect; a physical space which needs to be created for children to feel safe and comfortable; a social environment that needs to be warm and friendly for children to experience love and care and develop a stable and positive attitude towards life; a living environment which needs to be decorated and an educational environment that needs to be engaging so that children can learn. The environment is our surroundings, including one mention of the plants/animals and the need to prevent pollution. Additionally, it is advocated that children should engage with the everyday environment and the surroundings. Sustainability is missing completely, despite the fact that China is promoting sustainability and is robustly participating in the development of the Sustainable Development Goals. Moreover, kindergartens are conducting some projects about sustainability, especially from the environmental dimension [30]. The question raised in the Indian context about missing the terms also applies to China.

The curriculum describes nature as the natural physical world including plants and animals and landscapes, which children need to have knowledge about, as well as to respect and protect. Nature is also used to denote the embedded/essential characteristics of something substantial, which children should also have knowledge of.

Concepts of critical thinking, agency, children as participants and children’s rights elicit no mention in the Chinese guidelines. However, thinking is mentioned six times. It is stated there that teachers should encourage children to think and promote their logical and visual thinking. In addition to this, teachers are asked to promote and protect children’s curiosity. Although ‘voice’ as a term has been mentioned six times, it is only about how to help children to use their voices, not as articulation/expression of opinions and views.

Independent/independence is mentioned six times in the Chinese guidelines. Children are encouraged to make independent choices and take care of themselves in everyday life.

The concept of care is mentioned 19 times in the Chinese guidelines, as it talks about adults, especially teachers, taking care of children. At the same time, it promotes children developing abilities to take care of themselves, nature and the environment, as well as people around them, especially older adults.

4.3. Japan

The term ‘environment’ is mentioned 29 times in the Japanese national curriculum. Early childhood education in Japan is regarded ‘to educate young children through their environment’. This concept was first described in the revision in 1989 and has been regarded as highly important as a fundamental of early childhood education in the national curriculum. This ‘environment’ was defined as ‘everything surrounding a young child including the physical environment such as materials, toys and playground equipment; human environment, such as friends and teachers; nature and society; time, atmosphere’. Therefore, ‘environment’ means the learning environment for children in the Japanese national curriculum. According to this definition, nature is regarded just as one factor of the environment. This positioning of nature in early childhood education seems to reflect the view of nature in the modern world: nature is the resource for human activity, such as economy.

As for the term ‘nature’, we can find it 18 times. The terms ‘animals’, ‘plants’ and ‘seasons’ are used as facets of nature. In the Japanese curriculum, nature is one aspect of the learning environment which not only enhances children’s curiosity and logical thinking, but also influences children’s aesthetic sense and enriches our lives. The national curriculum describes ‘leading a life close to nature, being aware of its grandeur, beauty and wonder’. Although the national curriculum describes the significance of nature in early childhood education, nature is regarded as just a tool for children’s development; therefore, there are no descriptions about sustainability, protection of nature, ecosystems or biodiversity.

It is recommended that children independently explore their surrounding environment with curiosity. That way, they can discover things, think logically and develop skills to enrich their play. Therefore, thinking ability is described as important in the national curriculum. However, the translated Japanese term for the English term ‘critical’ might not create a positive impression for most Japanese because direct expression with critical nuances is not accepted in Japanese culture [22]. People are still required to respect elder persons, senior persons, persons with long experience or persons in a higher position, and saying something against them is regarded as rude. In the Japanese language, people still use different and complicated rhetoric towards such persons. In educational settings, therefore, children are required to develop their thinking abilities or logical thinking, but they are not used to thinking critically about school systems, teachers as older and more experienced persons or existing knowledge described in official textbooks. In this Japanese education culture, it seems to be difficult to think of children as active agents or active citizens. However, in 2017, all national guidelines from early childhood education to secondary education were completely revised, and some new concepts were introduced such as ‘proactive, interactive and authentic learning’ and ‘curriculum management’. This revision will change traditional Japanese education culture in the future.

The term ‘care’ has various meanings. In early childhood settings, teachers care for children. In Japan, there are three guidelines (national curriculum) for early childhood services: course of study for kindergarten (age 3–5), guidelines for care and education in nursery centres (age 0–5), course of study for centres for early childhood education and care (age 0–5). Descriptions about teachers’ care for children appear in the latter two guidelines. The Japanese guidelines require children to develop care about various things, such as animals, plants, people, materials and their own body.

Furthermore, Japan is frequently described as a collectivism- or groupism-based society, although this has been changing gradually in the modern era [31]. Cross-cultural psychologist Nisbet [32] revealed differences in attention, perception, cognition and social-psychological phenomena, such as the concept of self, between the Western and Asian cultural group. It might be specific to Japanese national curriculum describing the term ‘friends’ 16 times, and children are always required to care about other children, which encourages children to always think of others and recognise themselves as a part of a group.

5. Discussion and Conclusion Based on Comparison of Key Concepts across the Three Countries

None of the curriculum documents mention sustainability or environmental education as a standalone term, although the term ‘environment’ is frequently used in the curriculum. In Japan, there is a focus on learning environments which come to include physical and natural environments. In contrast, in India and China, the learning environment is seen as a physical space. For the three countries, environment is basically used as a term of pedagogy and does not mean the natural environment as a target of respect or protection in this Anthropocene Era.

The term ‘nature’ was also used frequently with all three countries providing similar views of nature—something that is ‘out there’. Our countries have long traditions of living harmoniously with nature. One of the reasons might come from the fact the cultures of our countries have been influenced by religions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism or Shintoism, which have different characteristics from Christianity. On the other hand, we did not hesitate to destroy nature during and after the Second World War, or the need for economic development. There is a traditional view of nature, therefore, that also sees nature as a resource that is meant for human use (and abuse), similar to the Western view of nature, when the times warrant. This perception of nature is probably one of the reasons why these countries have serious environmental problems and where sustainability is seen as anti-development. While there is some mention of nature-based learning, there is not a strong emphasis on this, but rather a superficial mention. Positioning ‘nature’ as a tool of teaching for children is a key issue that crops up in this work. This resource-oriented approach then leads to a disconnection between humans and nature. For building a sustainable society, a view of nature that goes beyond an economic tool towards a more holistic approach is absolutely necessary. The present education system that promotes nature merely as an educational tool for children’s development leads to more harm. It will be beneficial for the entire global audience to adopt the understanding that nature goes beyond a basic teaching tool into an entity of its own. One possible answer might be the fact that education systems and pedagogy themselves have been imported from the West and have not originated in each country, and rethinking indigenous and non-Western perspectives might provide an opportunity to look beyond this resource-oriented approach [8]. On the other hand, we have to clarify why our Asian traditional view of nature could not contribute to prevent various environmental issues in each country. As for Japan, looking into Totman’s works on the history of the Japanese forest and environment [33,34], it seems that the so-called ‘Japanese traditional view of nature’ did not function as a deterrent against the destruction of the natural environment. We may need a new view of nature for a sustainable society.

Care was a strong element in all the curricula. How this term was seen, however, differed in each context. In India, ‘care’ was basically used in terms of giving and nurturing relationships with parents, peers and teachers and also taking ‘care’ of belongings and property, with one mention of taking care of and protecting the environment and its relationships. In Japan, care was an emphasised in a similar way with connection to peers. In China, ‘care’ was seen in a similar context but also including taking care of nature and the environment.

Regarding children as participants with agency and voices, in all three countries, the view of children is as an individual, yet they are not seen as mini-adults. While curiosity and care are promoted in each of these cultures, there is a very different understanding of what their voice and agency means. Children actively participate in grown-up activities and are encouraged to be part of the overall system, yet there is a clear understanding that the adults make the rules and children learn to follow these and learn from them. The notion of ‘independence’ is also understood very differently. The emphasis is on moving towards ‘self-reliance’ rather than ‘independence’ from adults or society. The duty of care—whether it is towards one’s family, friends or society—is deeply embedded in these three cultural systems.

The term ‘critical thinking’ is also viewed very differently in each of these contexts. To a large extent, this is almost a philosophical shift in what ‘critical thinking’ means in these cultures, which can in fact come with some negative connotations. Children in these cultures are encouraged to follow elders, learn from centuries-old traditions and adapt these to modern society. The notion of ‘critical thinking’ in Western perspective in terms of questioning or arguing about these traditional knowledge systems is not promoted or encouraged in these education systems. All three cultures have strong hierarchical systems with clear decision-making roles for adults. These authoritative structures mean children are not allowed to challenge adults or critique their decisions. In many ways, children are taught (indoctrinated) to follow the authority systems from an early age, which, according to Bourdieu and Passeron [35], is the reproduction of dominant social structures.

6. Concluding Remarks

The study showcases the many opportunities within curriculum settings in India, China and Japan that could be harnessed to provide a different view of ESE. The colonial nature of our education system means we have imported the education systems, including theoretical and pedagogical views of education. A shift to strengthening the cultural roots, while at the same time being mindful of the influences of Western philosophies and resource-driven mindsets would provide opportunities for a more holistic approach to education. This consequently provides impetus for a global call for recognising similar indigenous cultural perspectives when shaping key policy documents, including the national curriculum content.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.A., A.H. and M.I.; Formal analysis, S.C.A., A.H. and M.I.; Methodology, S.C.A., A.H. and M.I.; Project administration, S.C.A.; Writing—original draft, S.C.A., A.H. and M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Monash University provided small internal grants funding to support the publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No applicable for this article does not involve human or animal subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Data of this article are policy documents listed in Table 1.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Colleen Keane for proof reading and formatting.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Description of key concepts in national ECE curriculum.

Table A1.

Description of key concepts in national ECE curriculum.

| Key Concepts | China | India | Japan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N 1 | How It Is Mentioned | N | How It Is Mentioned | N | How It Is Mentioned | ||

| Environ-ment | Learning environment/ educational environment | 25 | Physical and social environment in the KG Friendly and warm environment for children Children learn to adapt to it Teachers create rich and engaging educational environments | 25 | Mainly about surroundings, pollution, patterns Physical space/place that needs to be organised, child friendly Daily routines and design of the place | 29 | Learning environment Materials, friends, teachers, nature, society Early childhood education is “education through environment” which is created by teachers. |

| Natural environment | 1 | Children experience, discover beautiful things in natural environment | 2 | The outdoors as something to explore and manipulate Mentions birds and animals as a theme or concept for teachers | 1 | Free physical activity and play in a natural environment stimulates the development of bodily functions | |

| Sustainable society | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 1 | Children as builders of a sustainable society in the future Fostering the base for this during early childhood | |

| Nature | Nature (natural world, natural factors) | 19 | Have knowledge about it Appreciate it Experience the dependent relationship between human beings and nature Love, respect and protect it | 19 | Mainly as colours patterns and aesthetics | 16 | Lead a life close to it Being aware of its grandeur, beauty and wonder Be familiar with it To foster a sense of attachment and awe toward these things, as well as a respect for life, a spirit of social responsibility and An inquisitive mind |

| Nature (basic quality or character of something) | 3 | Have knowledge, e.g., understand the relative nature of capacity | 13 | Exploring nature and opportunities in nature | 2 | Understanding the nature of things | |

| Animals and plants | 6 | Have knowledge about them Experience humans’ relation with animals and plants Attend to them | 6 | All mentions are within examples for a theme that teachers can use in their routine | 5 | Be familiar with them to acknowledge, respect, appreciate “life” | |

| Season | 6 | Have knowledge about them Experience the changes of them and know how to make changes accordingly | 2 | As examples of a possible theme | 3 | Being aware of changes in nature and in people’s lives | |

| Outdoor | 18 | Participate in outdoor activities | 18 | Play, activities and interactions | 2 | Playing outdoor Place for children’s interest and curiosity | |

| Critical thinking | Critical thinking | 0 | NA | 1 | Develop critical thinking as part of cognitive development | 0 | NA |

| Thinking | 6 | Support children’s thinking Logical thinking Visual thinking | 13 | Thinking as cognitive development including sequential and higher order thinking | 5 | Thinking and acting independently Sharing thoughts with friends and understanding what friends are thinking | |

| Curiosity | 8 | Arouse and protect children’s curiosity Children being curious | 7 | Educators promote curiosity Children are curious Curiosity important for learning | 15 | Curiosity about health, various kinds of things, the concepts of quantities and diagrams, simple signs and written word | |

| Agency & Voice | Agency | 0 | NA | 2 | Voice is used as meaning talking voice not opinion/say | 0 | NA |

| Voice | 6 | How to use their voice | 2 | As in speaking voice and tone | 0 | NA | |

| Independent | 6 | Make independent choices Be independent to take care of themselves | 4 | As part of development stage where children act as independent Not about promoting independence | 12 | Voluntary Independently maintain a healthy and safe life Fostering self-reliance and developing voluntary activities It is important for teachers to encourage children’s voluntary activities in various ways | |

| Children Rights | Children’s Rights | 0 | NA | 1 | Inclusive education and the shift in special education from a medical model of care to a model of children’s rights | 0 | NA |

| Care | Teacher’s Care of children | 19 | Take care of children | 6 | Taking care of the development needs and well- being of the child and the child in general Teachers are caregivers translates into providing care | 0 | NA |

| Children’s care for/about/of | Children learn self-care skills Guide young children to show respect and care for the elderly and people around them, and respect for others’ work and its results | 38 | Mentioned as respect and care for elders, parents and teachers and care of common facilities. | 2 | Care of common play equipment and apparatus Treating their surroundings with care | ||

1 The number of mentions of the term in the reviewed policy documents.

References

- Ferreira, J.; Ryan, L.; Tilbury, D. Whole-School Approaches to Sustainability: A Review of Models for Professional Development in Pre-Service Teacher Education; ARIES: Canberra, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J. Young Children and the Environment: Early Education for Sustainability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran, P.; Walker, K.E.; Wals, A.E.J. Case studies, make-your-case studies, and case stories: A critique of case-study methodology in sustainability in higher education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2004, 10, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.; Moore, D.; Almeida, S.C. Empowering Teachers through Environmental and Sustainability Education: Meaningful Change in Educational Settings; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pramling-Samuelsson, I.; Li, M.; Hu, A. Early childhood education for sustainability: A driver for quality. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2019, 2, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. Revealing the research ‘hole’ of early childhood education for sustainability: A preliminary survey of the literature. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. Caring for the Environment—Towards Sustainable Futures. In Outdoor Learning Environments: Spaces for Exploration, Discovery and Risk-Taking in the Early Years; Little, H., Elliott, S., Wyver, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, S.C. Alternative worldviews on Early Childhood Education for Sustainability. In Researching Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: Challenges, Assumptions and Orthodoxies; Elliott, S., Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E., Davis, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M. ‘If there’s no sustainability our future will get wrecked’: Exploring children’s perspectives of sustainability. Childhood 2017, 24, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Coral and Speldewinde, Christopher, Early Childhood STEM Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1–11. Available online: https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:gam:jsusta:v:14:y:2022:i:6:p:3524-:d:773165 (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Sriprakash, A.; Maithreyi, R.; Kumar, A.; Sinha, P.; Prabha, K. Normative development in rural India: ‘School readiness’ and early childhood care and education. Comp. Educ. 2020, 56, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldermariam, K.; Boyd, D.; Hirst, N.; Sageidet, B.M.; Browder, J.K.; Grogan, L.; Hughes, F. A critical analysis of concepts associated with sustainability in early childhood curriculum frameworks across five national contexts. Int. J. Early Child. 2017, 49, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Kindergarten Education Guidelines. 2001. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3327/200107/t20010702_81984.html (accessed on 18 January 2018).

- Ministry of Education. Early Learning and Development Guidelines for Children Aged 3 to 6. 2012. Available online: http://old.moe.gov.cn//publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s7371/201305/152136.html (accessed on 18 January 2018).

- National People′s Congress. Constitution of the People′s Republic of China (2018 Amendment). 2018. Available online: http://www.mod.gov.cn/regulatory/2018-03/22/content_4807615.htm (accessed on 18 January 2018).

- Ministry of Human Resource Development. National Education Policy 2020. Available online: https://www.mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NEP_Final_English_0.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Ministry of Women Child and Development. National Early Childhood Care and Education Framework. 2013. Available online: https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/national_ecce_curr_framework_final_03022014%20%282%29.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Japan). Course of Study for Kindergarten (Youchien Kyoiku Yoryo). 2017. Available online: https://www.mext.go.jp/content/1384661_3_2.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2022). (In Japanese)

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Japan). Guidelines for Care and Education in Nursery Centres (Hoikusho Hoiku Shishin). 2017. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-11900000-Koyoukintoujidoukateikyoku/0000160000.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2022). (In Japanese)

- Cabinet Office, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology & Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Japan). Course of Study for Centrers for Early Childhood Education and Care (Youhorenkeigata Nintei Kodomoen Kyoiku Hoiku Yoryo). 2017. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/web/t_doc?dataId=00010420&dataType=0&pageNo=1 (accessed on 6 July 2022). (In Japanese)

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Professional Standards for Kindergarten Teachers. 2012. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A10/s6991/201209/t20120913_145603.html (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Inoue, M. Perspectives on early childhood environmental education in Japan: Rethinking for a sustainable society. In Research in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: International Perspectives and Provocations; Davis, J., Elliott, S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grindheim, L.T.; Bakken, Y.; Hauge, K.H.; Heggen, M.P. Early childhood education for sustainability through contradicting and overlapping dimensions. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2019, 2, 374–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, K. Bringing the jellyfish home: Environmental consciousness and ‘sense of wonder’ in young children’s encounters with natural landscapes and places. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 1139–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A. Critical Thinking: An Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1990. Available online: https://www.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/UNCRC_PRESS200910web.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Bakhtin, M. The Dialogic Imagination; Holquist, M., Ed.; Emerson, C.; Holquist, M., Translators; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- MWCD National Early Childhood Care and Education Policy, Gazette of India, Part I Section 1, no. 6–3/2009 ECCE. 2013. Available online: https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/National%20Early%20Childhood%20Care%20and%20Education-Resolution.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Sobel, D. Childhood and Nature: Design Principles for Educators; Stenhouse Publishers: Portland, OR, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Zhou, X.; Cui, H. Exploring education for sustainable development in a Chinese kindergarten: An action research. ECNU Rev. Educ. 2019, 2, 497–514. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2096531119897638 (accessed on 25 October 2020).

- Hamamura, T. Are cultures becoming individualistic? A cross-temporal comparison of individualism–collectivism in the United States and Japan. PubMed Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 16, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, R. The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently...and Why; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Totman, C. Nihonjin ha Donoyouni Mori wo Tukuttekitaka (The Green Archipelago: Forestry in Pre-Industrial Japan (Originally Published in 1989); Kumazaki, M., Translator; Tsukiji Shokan: Tokyo, Japan, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Totman, C. Nihonjin ha Donoyouni Shizenn to Kakawattekitanoka (Japan: An Environmental History (Originally Published in 2014); Kuroda, R., Translator; Tsukiji Shokan: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P.; Passeron, J.-C. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, 2nd ed.; Nice, R., Translator; Sage: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).