1. Introduction

The discourse on environmental sustainability stresses worldwide environmental challenges requiring immediate remedies [

1,

2,

3]. Since excessive industrial activities lead to ecological imbalance [

4,

5], the effect of business strategies and practices on the environment has garnered growing social attention [

6,

7]. Increasing environmental concerns, including climate change and depletion of natural resources, have prompted businesses to reduce their influence on the natural environment [

5]. Climate change is currently the most pressing issue on a worldwide scale, with Bangladesh being the most susceptible [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Bangladesh will incur substantial losses if the current situation persists, and it is projected that the annual loss will amount to 2% and 9.4% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 2050 and 2100, respectively, even though Bangladesh is liable for less than 0.35% of global carbon emissions [

12]. Thus, businesses, particularly SMEs, have a pivotal role in attaining sustainable development goals by enhancing environmental practices. Prior research has demonstrated that SMEs are unaware of ecological legislation and reluctant to embrace eco-friendly production and environmental conservation [

13]. Today, however, the situation has altered for manufacturing SMEs, as they rely heavily on formal credit from banks and other financial institutions. According to the Central Bank’s guidelines, these SMEs must implement environmental and social risk management (ESRM) to secure a bank loan [

14].

Given that businesses are fundamental economic units and play a vital role in economic growth and environmental degradation, it is crucial to analyze the influence of business strategy on environmental performance (ENP) and financial performance (FP). Considering the importance of business strategy in a firm’s performance, Kong et al. [

15] argued that businesses should modify their operational processes to incorporate environmental sustainability. Given the rising depletion of natural resources, ecological degradation, and pressures from consumers, vendors, and other stakeholders, firms are adopting environmental strategies (ENS) [

16,

17]. ENS are the environmental objectives, procedures, and practices that go beyond merely adhering to environmental laws and regulations [

17]. Companies adopting ENS can better foresee future ecological challenges, explore new prospects, and deal with societal issues more efficiently [

18]. They are more likely to lessen their environmental impact, while attaining superior financial results [

5,

19]. Recent studies reported that firms’ ENS could substantially enhance their green innovations [

16,

20], corporate sustainability development [

21], and overall organizational performance [

5,

17]. In a similar vein, this study contends that firms’ environmental strategy can positively impact their environmental and financial performance.

Firms’ environmental awareness (ENA) has been documented to be pivotal in driving sustainable competitive advantage and firm performance in the firm-level ENA literature [

22,

23]. Businesses must increase environmental awareness to give employees a lasting understanding of the organization’s environmental-management strategy, environmental policy, and ecological ramifications [

24]. Organizations need to supply all employees with the information necessary to identify environmental concerns and circumstances, make the proper decisions, and take the relevant actions, in addition to their core job responsibilities [

25]. ENA promotion necessitates an in-depth comprehension of environmental concerns, which is an effective means of enhancing environmental behaviors and sustainable performance [

26]. The prior literature has established that environmental awareness positively relates to green competitive advantage [

22]. Managers’ environmental awareness and enterprises’ environmental strategy jointly affect environmental protection and overall organizational performance [

27]. An organization’s green conduct may suffer without green environmental awareness among its business managers. Firms’ ENA is crucial for implementing circular economy practices and sustainable operations [

28]. Zameer et al. [

29] noted a research gap and urged studies on the emergence of ENA and the subsequent evolution of businesses in implementing energy-efficient and environmental strategies for improving performance. Previously, most of the research has focused on the environmental awareness of customers [

30]. In the firm-level ENA context, just a few studies have been conducted, and their emphasis has been on techniques to foster environmental consciousness among managers [

31]. Academic study on translating ENA into ENP through corporate strategy is sparse. Moreover, corporate environmental concern is crucial to a company’s and society’s sustainable growth [

29].

Prior research has highlighted the role of ENS in enhancing a business’s environmental and financial performance [

4,

5,

17,

32]. Nonetheless, some contradictory findings also exist in the literature [

33]. Scholars have provided several explanations for this discrepancy, such as the characterization of environmental strategy [

18], the exclusion of critical mediating factors [

34], and the moderating functions of conditions [

5]. However, this scholarly discrepancy is problematic. It is crucial for management scholars to determine if the impacts of different ENS on a company’s competitiveness and performance stem from various resource requirements and endowments. In addition, practitioners must be aware of the intervening factors needed to execute an environmental strategy successfully. Otherwise, such techniques are likely to affect an organization’s performance negatively. We contend that the competitive advantage of firms mediates the linkages between ENS and ENP, ENS and FP, ENA and ENP, and ENA and FP. Furthermore, it should be highlighted that studies on the effects of environmental strategies are limited to a few distinct contexts. Scholars have mainly focused on several industries, including the hotel sector [

35], IT sector [

36], logistic services [

17], and the wine industry [

37]. However, there is a dearth of studies assessing the impacts of ENS and ENA on SME manufacturers, indicating the need for additional research that considers the context of the manufacturing industry. Manufacturing companies in Bangladesh are now taking corporate environmental and social responsibility into account, while making decisions and taking action [

38]. Moreover, Masud et al. [

9] and Bae et al. [

8] argue that local regulation (CSR rules, green finance standards, money-laundering laws, and environmental risk-assessment rules) and international CSR standards have had a significant impact on Bangladeshi manufacturing firms to enhance ecological management practices. In addition, the SME policy and the Bangladesh bank have enacted several environmental laws to facilitate SME access to formal credit [

14].

In addition, most prior research has focused on enterprises in developed and Western nations, which have differing managerial attitudes and cultural and legal contexts compared to developing and Eastern nations [

39]. Despite several scholarly efforts to demonstrate the advantages of ENS and ENA, there is a paucity of empirical findings from emerging economies [

39,

40]. For instance, Ryszko [

41] studied the effect of ENS on firms’ operational and financial performance in 292 firms operating in Poland. Leonidou [

6] studied 216 Vietnamese firms to assess the effect of environmental strategies on firms’ competitive advantage and performance. Similarly, Laguir et al. [

17] investigated the role of ENS and green practices on the ENP and FP of 232 logistic service providers in France. Only a few studies have assessed the critical functions of ENS and ENA on organizational performance in the emerging economy context [

5,

23,

42].

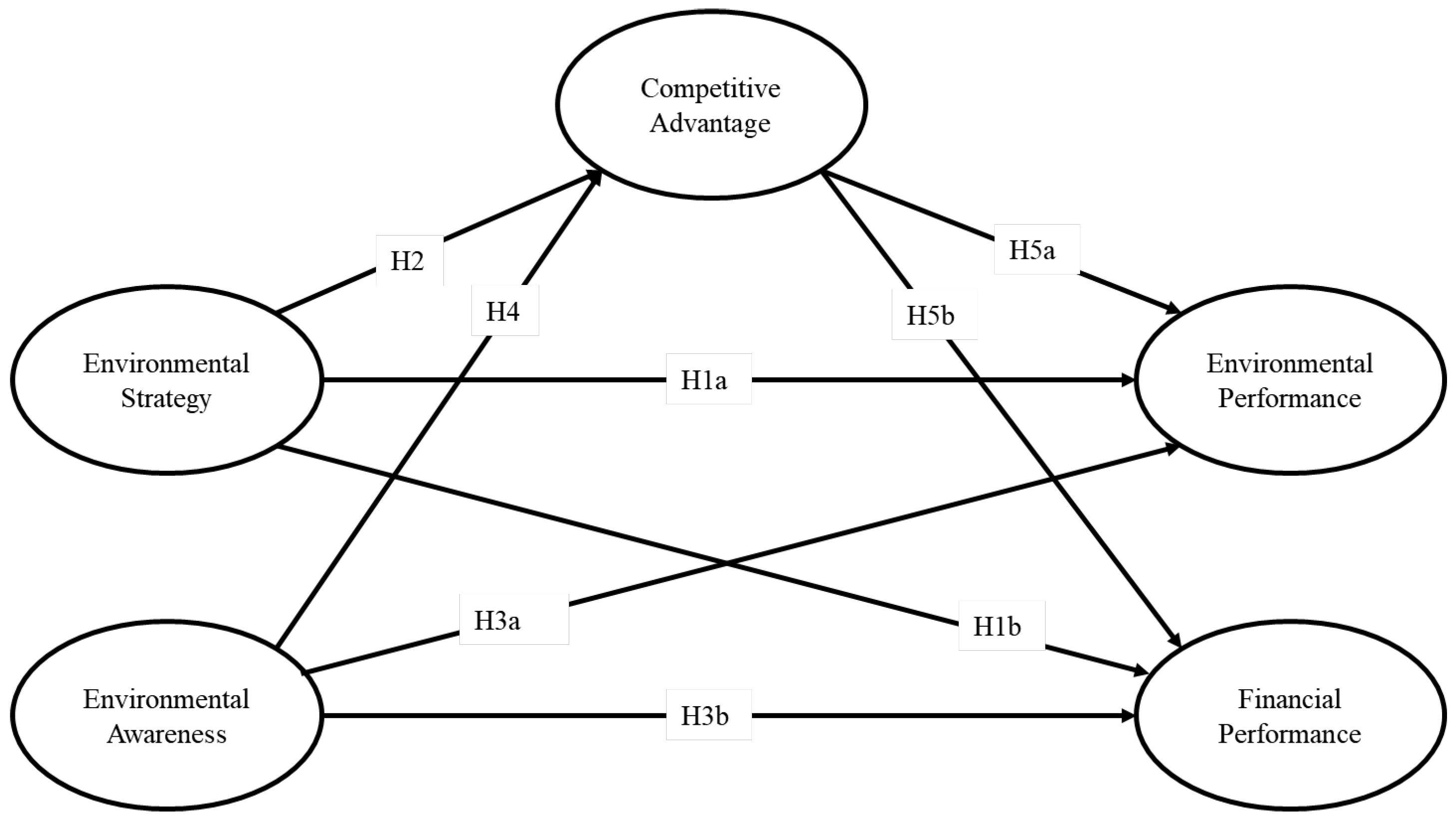

The center of this research is the question, “do environmental strategy and environmental awareness affect organizational performance?” We dissect the variation across two critical organizational performance indicators to answer this question. Consequently, our study question may be put more precisely as follows: do environmental strategy and awareness individually and collectively contribute to firms’ environmental and financial performance? In addition, by investigating the mediating function of businesses’ competitive advantage, we address the following issue: does competitive advantage mediate the relationship between environmental strategy and firm performance, as well as the relationship between environmental awareness and firm performance? Our study adds to the emerging literature on ENS and ENA in multiple ways by addressing these questions. We used the NRBV theory as a theoretical lens to explore the interplays between ENS and firms’ ENP and FP and the associations between ENA and ENP and FP. Hence, our investigation of the complex linkages between these variables and the role of firms’ competitive advantage extends the extant knowledge body.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The study assessed the role of environmental strategy and environmental awareness in improving firms’ environmental and financial performance through enhanced competitive advantage. Drawing on the NRBV theory, this research empirically tested the linkage between ENS and ENP, ENS and FP, ENA and ENP, and ENA and FP. We also examined the mediating impact of competitive advantage of firms among these associations.

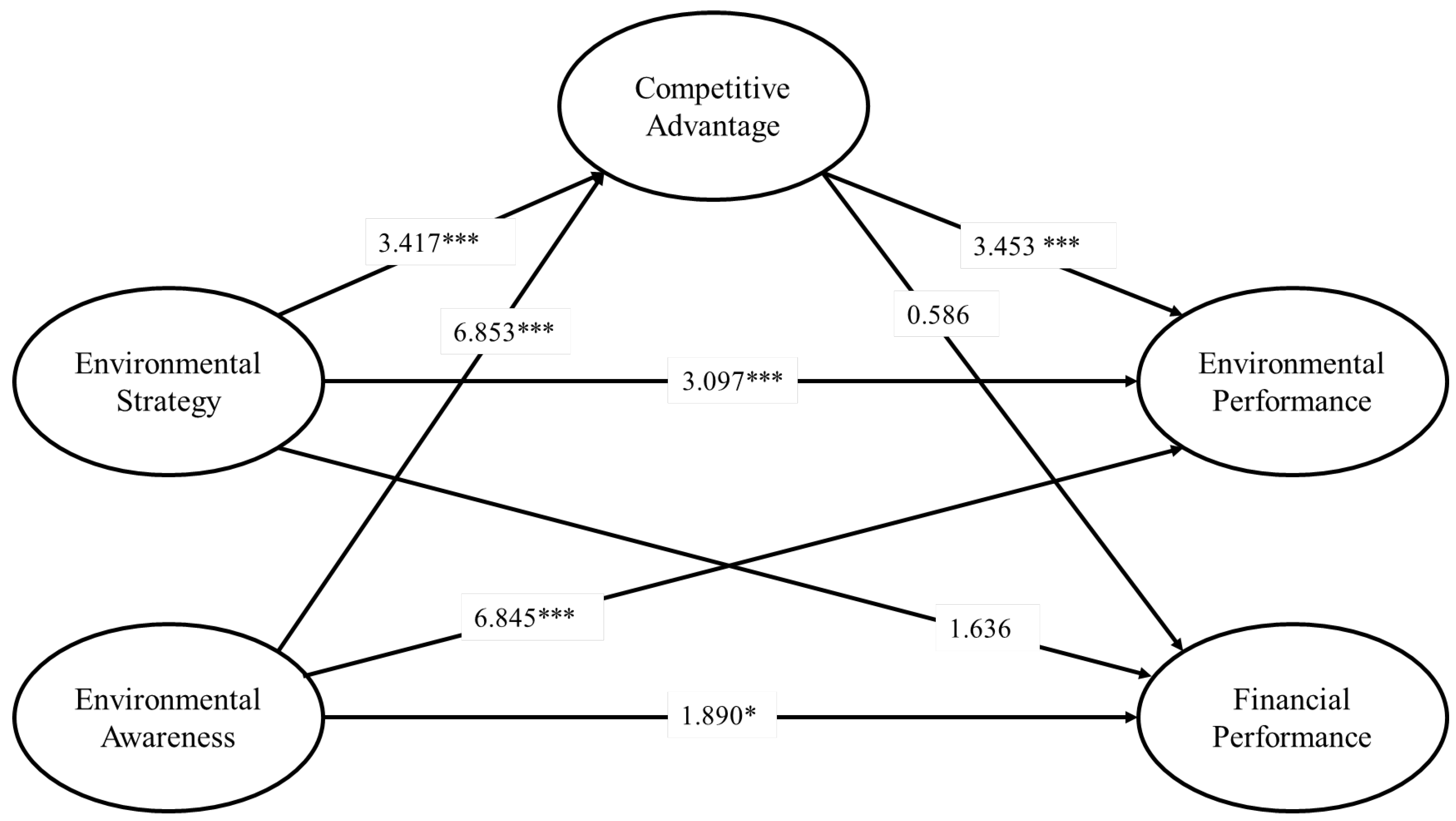

The study hypothesized (H1a) that environmental strategies significantly impact the environment. The results of the SEM demonstrate that ENS favorably affects the ENP of Bangladeshi manufacturing SMEs, thereby validating Hypothesis 1a. Previous studies in the domains of ENS and sustainability corroborate this suggestion [

17,

19,

34]. Laguir et al. (2021) report that companies with an ENS are more likely to create a shared long-term strategy with their stakeholders, to preserve the environment and ensure sustainable growth, which is a unique source [

45] for enhancing environmental performance. This finding adds to the NRBV literature, indicating that business strategy (particularly ENS) is a strong predictor of firms’ improved ENP through effective resource allocation [

34,

45].

On the other hand, this study’s findings could not establish a significant association between firms’ ENS and financial performance; thus, hypothesis H1b was rejected. This finding contrasts with previous studies by Banerjee [

68] and Do and Nguyen [

39], which argued that adopting ENS increases company performance by boosting operations, reducing waste and energy consumption, and utilizing recyclable materials. However, most of these studies explored the role of ENS in boosting overall firm performance. There is a paucity of empirical evidence on the impact of ENS on the superior financial performance of organizations. Moreover, ENS cannot alone drive the financial performance of manufacturing firms. The existing literature reports that despite having ENS, Bangladeshi manufacturing SMEs are falling behind in adopting green manufacturing practices, mainly due to financial constraints and green technologies [

95]. Besides, there is a lack of strict environmental regulations for SMEs in Bangladesh [

9]. Thus, Bangladeshi manufacturing SMEs need to be trained to leverage their ENS into organizations’ financial performance by enhancing green innovation and competitive advantage.

As posited in H2, ENA positively affects firms’ competitive advantage. This result is in line with previous research examining the role of ENA in enhancing firms’ competitiveness [

66,

73]. The literature also suggests that firms adopting proactive ENS can achieve a low-cost and distinct competitive advantage [

39]. Moreover, firms can enjoy a cost advantage by reducing adverse impacts of noncompliance and ecological risks, saving money through regulatory incentives, undergoing minimal environmental inspections, and paying less for coverage [

71]. Hence, competitive advantages such as cost benefits and differentiation can be attained through firms’ environmentally oriented strategies.

Next, the findings unveiled that organizations’ environmental awareness substantially affects ENP. It implies that firms that appoint environmentally concerned managers and staff can attain superior environmental performance, since the management is aware of the environmental threats and climate change issues. This finding confirms previous study findings in this research area that link ENA with firms’ ENP [

23,

58]. We also found that ENA has a positive linkage with organizational financial performance. This output is in accordance with prior works [

53,

120]. Environmental consciousness is more likely to lead to improved relationships with external stakeholders, including governments, shareholders, and financial institutions, which can boost a company’s financial performance through reduced interest rates and investor confidence.

The findings also suggested that ENA is a crucial driver of firms’ competitive advantage (H4). A good number of the previous literature works have confirmed the substantial effect of ENA on the competitive advantage of businesses [

23,

83]. Firms’ ENA strongly drives green product innovation, a unique method for companies to enhance their competitiveness. A higher degree of environmental concern can facilitate firms to achieve competitive advantages, such as cost–benefit and differentiation in the industry. Further, the result indicated that competitive advantage is a necessary antecedent of firms’ environmental performance. This is in line with past research conducted by Zameer et al. [

121], which reported that a green competitive advantage could strongly drive organizational ENP. However, there is a dearth of research exploring the linkage between competitive advantage and firms’ ENP.

However, H5b was not supported, since the empirical evidence suggested that the effect of firms’ competitive advantage on financial performance is insignificant. This result contradicts several examples from the literature establishing the role of competitive advantage in enhancing firms’ performance [

39,

86,

122]. This conflicting finding could arise due to contextual differences. For instance, according to Wahyuni et al. [

82], the competitive advantage of enterprises is an insignificant determinant of financial performance among Indonesian real estate companies. Firms explicitly adopting a cost-leading competitive strategy in a fiercely competitive environment would face severe pressure on their manufacturing costs to maintain their top spot, barring them from outperforming their competitors [

90]. As predicted in H6 and H8, we noticed that competitive advantage mediates the linkage between ENS and ENP and ENA and ENP.

These findings corroborate extant literature that reported that the linkages between ENS and ENP and ENA and ENP are not direct but rather are mediated by intervening factors. However, there is limited research investigating the mediating role of competitive advantage in the interplays between ENS and ENP and ENA and ENP. Most research identified environmental-management accounting [

19,

34], the green supply chain process [

123], technological eco-innovations [

67], and environmental reputation [

124] as significant mediators between ENS and ENP. Thus, this new finding extends the ENS literature. Moreover, the mediating effect of competitive advantage between the ENA and ENP is also a new addition to the extant knowledge body, since most studies explored the direct effects of ENA on CA and ENP [

22,

29,

53]. However, this research could not establish any mediating effect of firms’ competitive advantage on ENS–FP and ENA–FP linkages.

6. Theoretical Implications

Our research has made crucial theoretical contributions in three ways: a new conceptual model comprising new constructs, a new context, and new outcomes. First, this work contributes to the NRBV literature by addressing current demands to examine the cumulative influence of resources on ENP and determine what initiates this capacity’s emergence [

46]. This research presents empirical support that ENS is a method that firms may utilize to enhance the generation of competitive advantage, which can impact their ENP. In addition, the NRBV is supported by a large body of work that examines the impact of ENS on enterprises’ competitive advantage and ENP. However, there is a dearth of research in the field of environmental management explaining the influence of ENA on the ENP of enterprises. This study expands the NRBV by defining ENA as a company’s internal resource that can generate superior ENP through competitive advantage. Second, this is one of the few studies that assess the combined effect of ENS and ENA on organizational competitive advantage, ENP, and FP. Our complex conceptual framework contributes to the environmental-management literature by illustrating the interplays between ENS, ENP, CA, ENP, and FP. Given the abundance of studies investigating the role of corporate environmental aspects on ENP, there is a paucity of research on the linkages between these environmental characteristics of firms and their financial performance. Our research is one of the few emerging studies that explored this linkage.

Third, this paper provides fresh quantitative insights into the impact of ENS and ENA on the performance of enterprises in developing countries. This study assessed the influence of ENS and ENA on organizational competitive advantage and performance in a developing country such as Bangladesh, as suggested by previous research. As far as the researchers are concerned, no empirical study has been uncovered that investigates the effect of ENS and ENA in enhancing organizational performance in Bangladesh. In addition, this study gathered data from manufacturing SMEs that actively engage in production that adversely affects the natural environment. Thus, this industrial context would also expand the existing corpus of knowledge.

Finally, the outcome of this scholarship contributes extensively to the ENS, ENA, and environmental-management literature. A voluminous literature has explored the role of different mediating factors such as environmental-management accounting [

19,

34], the green supply chain process [

123], technological eco-innovations [

67], and environmental reputation [

124] in the association between ENS and ENP. Thus, our findings add new insights into the ENS literature by establishing the significant intervening effect of firms’ competitive advantage in improving environmental performance. We argue that this study uncovers two of the most influential factors of enterprises’ environmental performance in a developing nation and records results that can be applied to the firms in these regions. This experimental study aimed to reconcile the theoretical research gap by analyzing and validating a new model employing SEM analysis. Moreover, environmental performance and financial performance are two of the critical components of the organizational triple-bottom-line (TBL) sustainability performance. Thus, our findings also contribute to the sustainability literature by identifying the crucial drivers of SMEs’ environmental and financial sustainability performance.