Spatial–Temporal Correlation between the Tourist Hotel Industry and Town Spatial Morphology: The Case of Phoenix Ancient Town, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

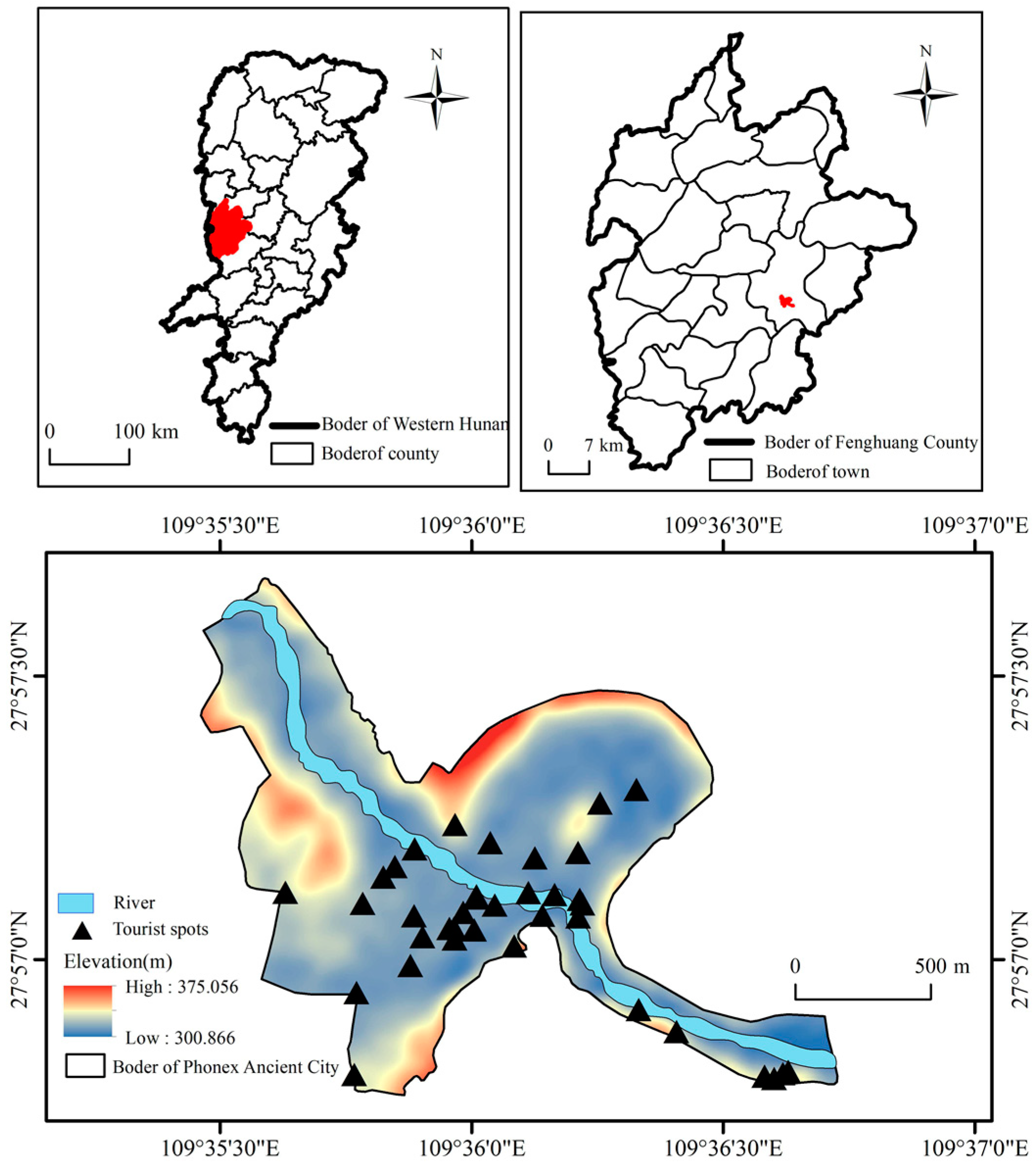

3.1. Study Area

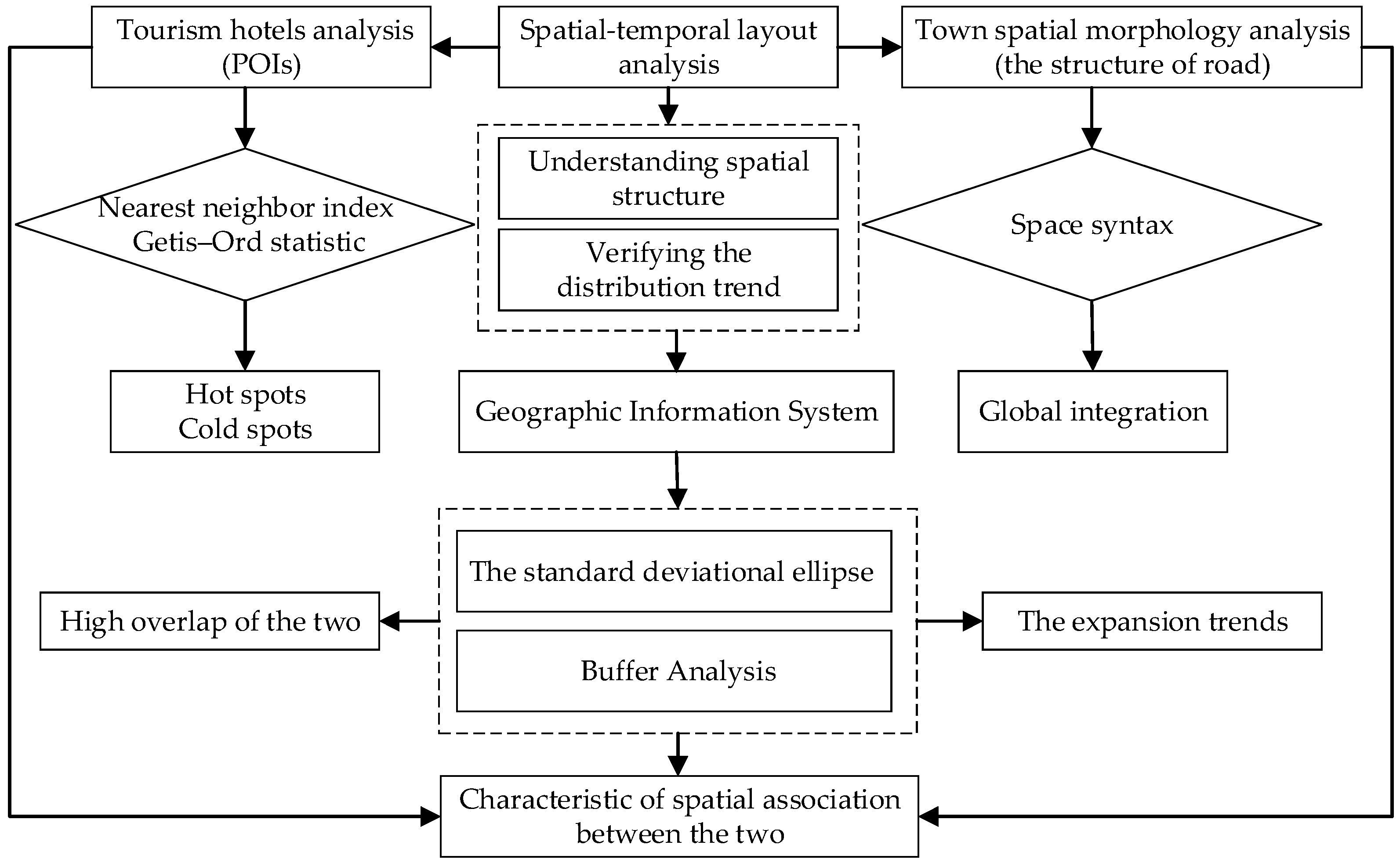

3.2. Methodology

3.3. Data Source and Processing

4. Findings

4.1. The Characteristics of the Tourist Hotel Industry Agglomeration

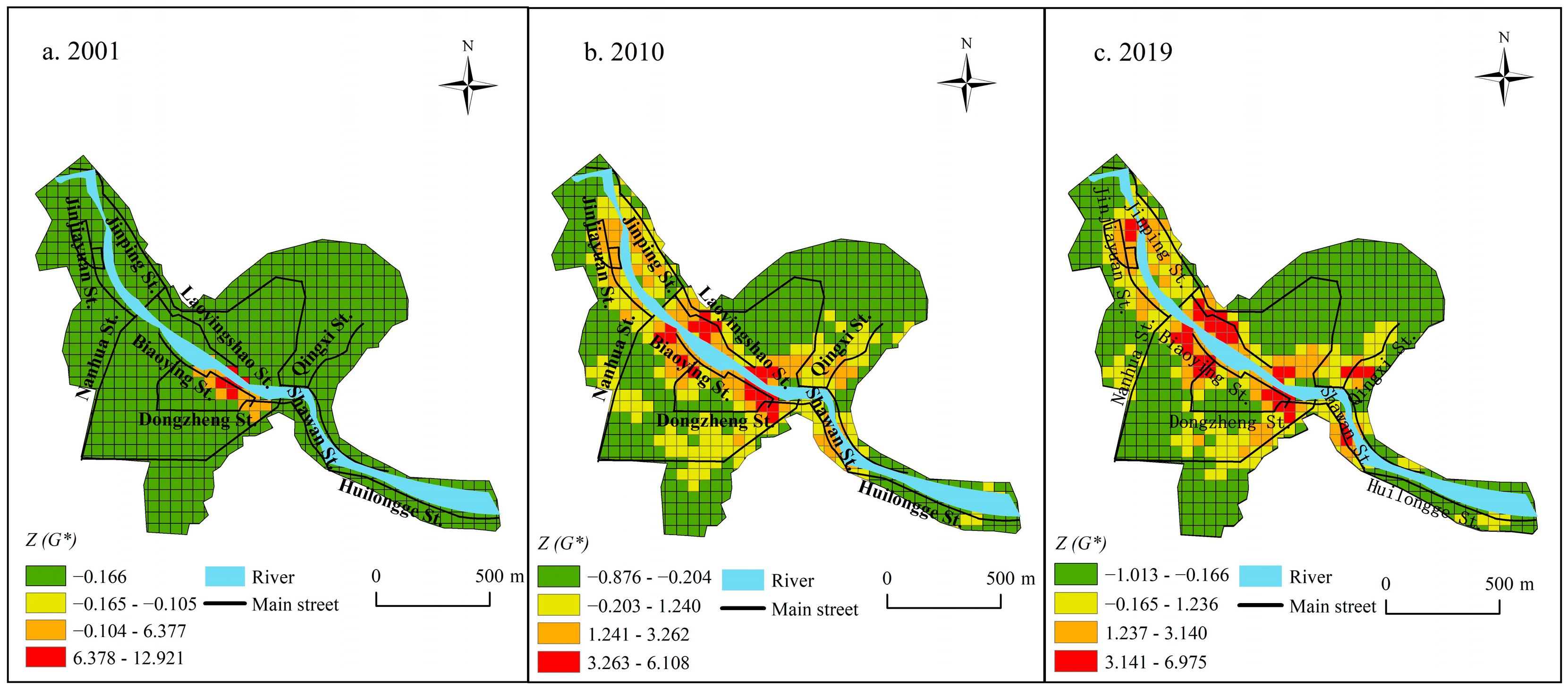

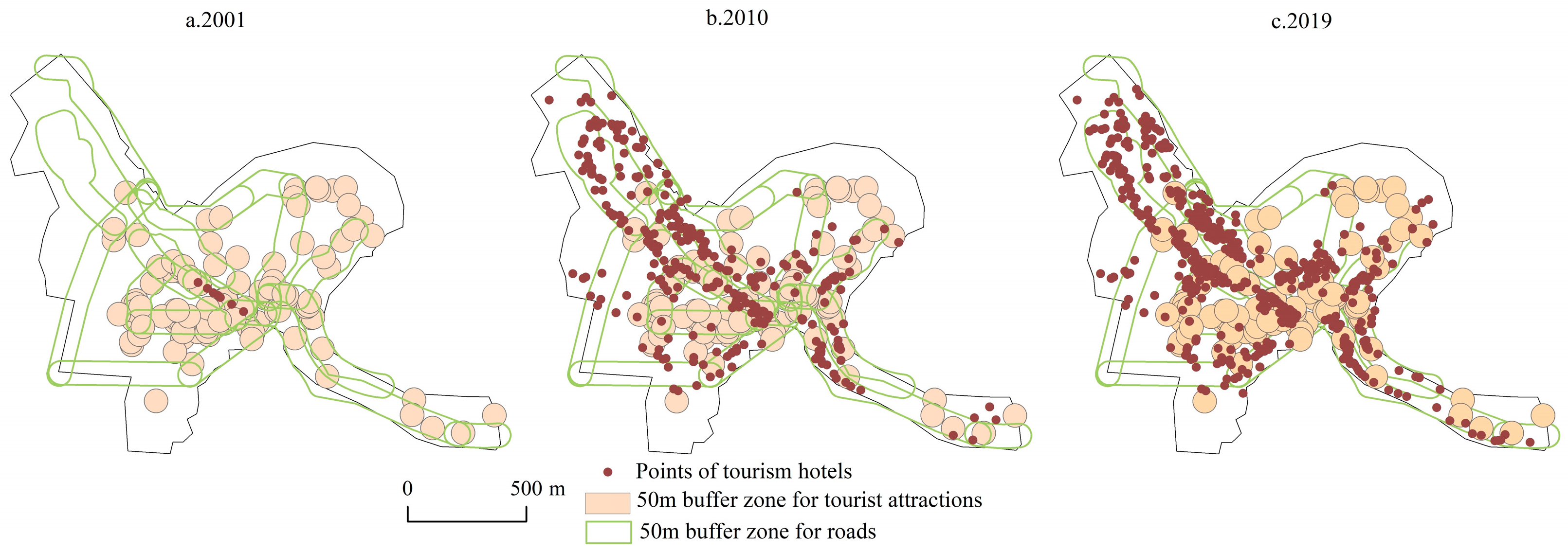

4.2. The Characteristics of the Hot Spots in the Tourist Hotel Industry

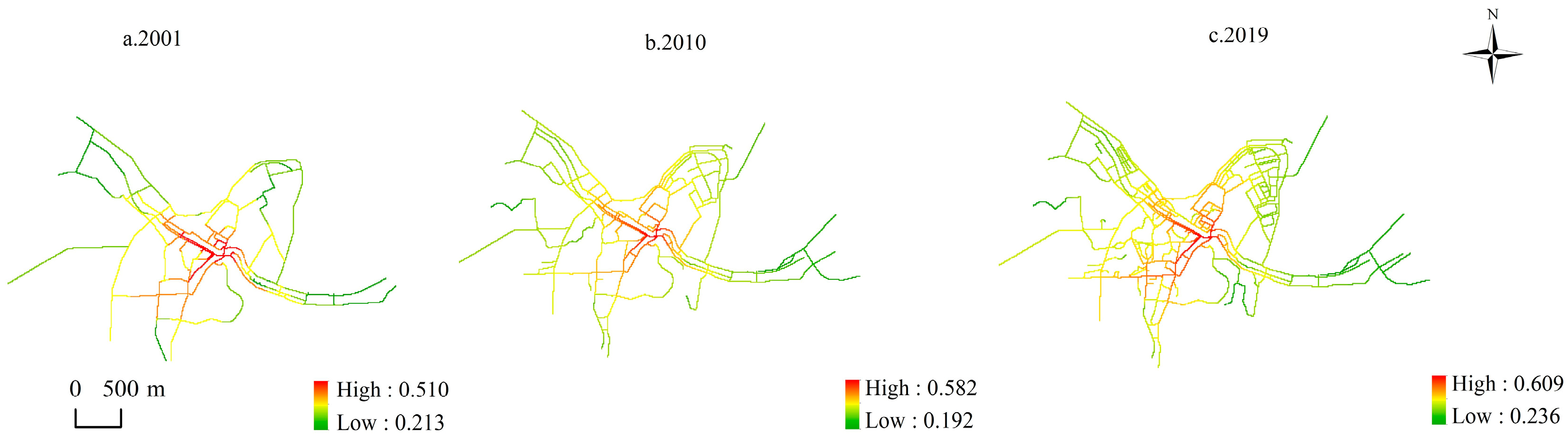

4.3. The Spatial–Temporal Evolution of the Town’s Spatial Morphology

4.4. Spatial Association between the Tourist Hotel Industry and the Town’s Spatial Morphology

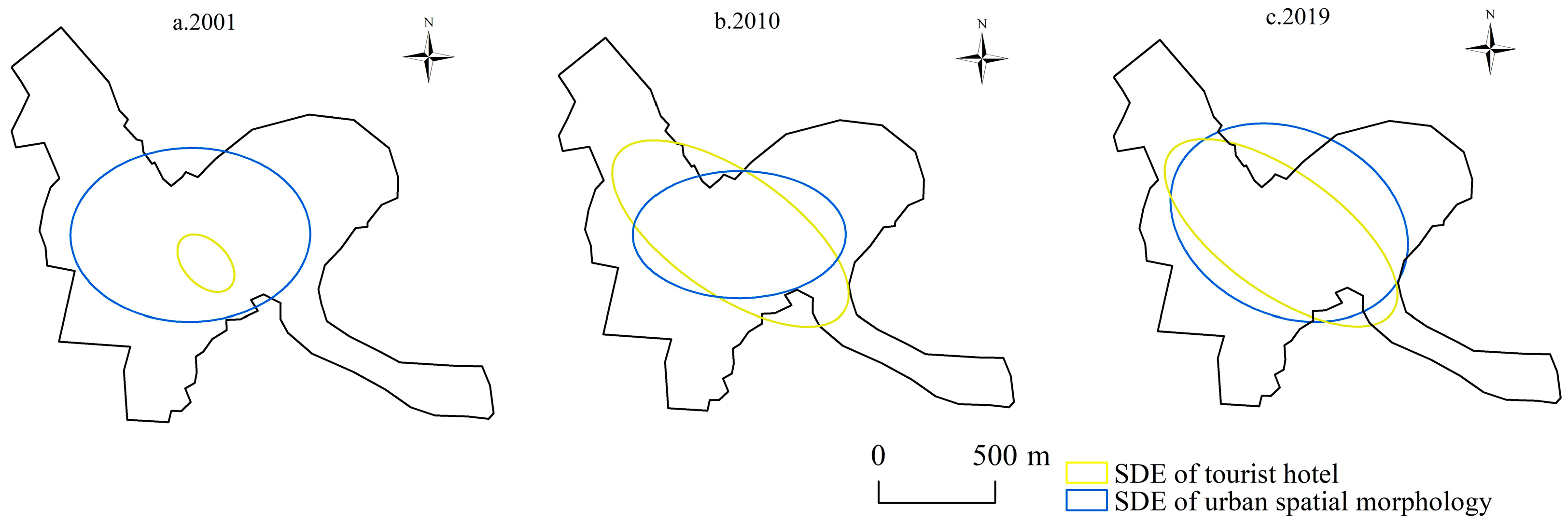

4.4.1. The Expansion Trends in the Growth of the Tourist Hotel Industry and the Town’s Spatial Morphology

4.4.2. High Overlap of the Tourist Hotel Industry and the Town’s Spatial Morphology

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Summary and Conclusions

5.2. Discussion and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Gong, Z.; Cao, K. Dynamic assessment of tourism carrying capacity and its impacts on tourism economic growth in urban tourism destinations in China. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zang, H.; He, Q. Urban space reshaping based on regional urban design: A case study of urban design of Taiping Bay Wharf Area in Yantai City. J. Landsc. Res. 2021, 13, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Solnet, D.; Paulsen, N.; Cooper, C. Decline and turnaround: A literature review and proposed research agenda for the hotel sector. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagliero, L.; Quatra, M.; Apiletti, D. From hotel reviews to city similarities: A unified latent-space model. Electronics 2020, 9, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Fujiki, Y. Evolution characteristics of the spatial network structure of tourism efficiency in China: A province-level analysis. J. Des. Mark. Manag. 2020, 18, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Voda, M.; Wang, K.; Chen, L.; Ye, J. Spatial network structure of the tourism economy in urban agglomeration: A social network analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadewo, E.; Syabri, I.; Antipova, A.; Pradono; Hudalah, D. Using morphological and functional polycentricity analyses to study the Indonesian urban spatial structure: The case of Medan, Jakarta, and Denpasar. Asian Geogr. 2021, 38, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garica, M.A.; Nicolini, R.; Roig, J.L. Segregation and urban spatial structure in Barcelona. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2020, 99, 749–772. [Google Scholar]

- Rogerson, C.M. Apartheid hotels: The rise and fall of the ‘non-white’ hotel in South Africa. New Directions in South African. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, D. The hotel and the city. Progr. Human Geogr. 2008, 32, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.; Boe-Gibson, G.; Stichbury, G. Urban land expansion in India 1992–2012. Food Policy 2015, 56, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, Y.; He, S.; Shaw, D. From development zones to edge urban areas in China: A case study of Nansha, Guangzhou City. Cities 2017, 71, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Yu, G.; He, Z. Origin, spatial pattern, and evolution of urban system: Testing a hypothesis of “urban tree”. Habitat Int. 2017, 59, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, P.; Neira, M.; Hermida, A. Historic relationship between urban dwellers and the Tomebamba River. Int. J Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 2017, 6, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, R. Urban morphology and preservation in Spain. Geogr. Rev. 1985, 75, 265–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya, B.; Syafri, A.; Sahban, H.; Sakti, H. Spatial Transformation of new city area: Economic, social, and environmental sustainability perspective of Makassar City, Indonesia. J. Southwest Jiaotong Univ. 2020, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lu, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, M. Cultivating historical heritage area vitality using urban morphology approach based on big data and machine learning. Comput. Environ. Urban 2022, 91, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Wu, J.; Yang, Z. Spatial pattern of urban functions in the Beijing metropolitan region. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lityński, P.; Serafin, P. Polynuclearity as a spatial measure of urban sprawl: Testing the percentiles approach. Land 2021, 10, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xiao, L.; Ye, Y.; Xu, W.; Law, A. Understanding tourist space at a historic site through space syntax analysis: The case of Gulangyu, China. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitali, R.; Snoussi, M.; Kolker, A.; Qujidi, B.; Mhammdi, N. Effects of land use/land cover changes on carbon storage in North African Coastal Wetlands. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza, M.; Dirus, m.; Malavasi, M.; Francesco, M.; Acosta, A.; Stanisci, A. Urban expansion depletes cultural ecosystem services: An insight into a Mediterranean coastline. Rend. Lincei-Sci Fis. 2020, 31, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, I.; Mensah, A. Perceived spatial agglomeration effects and hotel location choice. Anatolia 2014, 25, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wong, K.; Wang, T. How do hotels choose their location? Evidence from hotels in Beijing. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urtasun, A.; Gutiérrez, I. Hotel location in tourism cities: Madrid 1936–1998. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, N. The geography of hotels in cities: An empirical validation of a forgotten model. Tour. Geogr. 2006, 8, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnins, A.; Chung, W. Resource-seeking agglomeration: A study of market entry in the lodging industry. Strat. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.A.; Haveman, H.A. Love thy neighbor? Differentiation and agglomeration in the Manhattan hotel industry, 1898–1990. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 304–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.; García-Palomares, J.C.; Romanillos, G.; Salas-Olmedo, M.H. The eruption of Airbnb in tourist cities: Comparing spatial patterns of hotels and peer-to-peer accommodation in Barcelona. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Agglomeration density and tourism development in China: An empirical research based on dynamic panel data model. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1347–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fang, L.; Huang, X.; Goh, C. A spatial–temporal analysis of hotels in urban tourism destination. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 45, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoval, N.; Cohen-Hattab, K. Urban hotel development patterns in the face of political shifts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 908–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrinaga, C.; Vallejo, R. The origins and creation of the tourist hotel industry in Spain from the end of the 19th century to 1936. Barcelona as a case study. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budović, A.; Ratkaj, I.; Antić, M. Evolution of urban hotel geography—A case study of Belgrade. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lu, L.; Xu, Y.; Sun, X. The spatio-temporal evolution and influencing factors of hotel industry in the metropolitan area: An empirical study based on China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e231438. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. The new structure of building provision and the transformation of the urban landscape in metropolitan Guangzhou, China. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 259–283. [Google Scholar]

- James, K.J.; Sandoval-Strausz, A.K.; Maudlin, D.; Peleggi, M.; Humair, C.; Berger, M. The hotel in history: Evolving perspectives. J. Tour. Hist. 2017, 9, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Xie, Y.; Liu, T. Agglomeration and/or differentiation at regional scale? Geographic spatial thinking of hotel distribution—A case study of Guangdong, China. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1358–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stéphane, B. The geography of a tourist business: Hotel distribution and urban development in Xiamen, China. Tour. Geogr. 2000, 2, 448–471. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, S. Spatial analysis of public health facilities in Riyadh Governorate, Saudi Arabia: A GIS-based study to assess geographic variations of service provision and accessibility. Geo. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2016, 19, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ord, J.K.; Getis, A. Local spatial autocorrelation statistics: Distributional issues and an application. Geogr. Anal. 1995, 27, 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. From axial to road-centre lines: A new representation for space syntax and a new model of route choice for transport network analysis. Environ. Plann. B Plann. Des. 2007, 34, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, S.; Kamruzzaman, M. Meta-analysis of the relationships between space syntax measures and pedestrian movement. Transp. Rev. 2018, 38, 524–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meten, M.; Bhandary, N.P.; Yatabe, R. GIS-based frequency ratio and logistic regression modelling for landslide susceptibility mapping of Debre Sina area in central Ethiopia. J. Mount. Sci. 2015, 12, 1355–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbert, V.Z.; Dario, B.; Dominique, V. Distribution of tourists within urban heritage destinations: A hot spot/cold spot analysis of TripAdvisor data as support for destination management. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Long, F.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Yu, H.; Jiang, H. Development characteristics and evolution mechanism of homestay agglomeration in Mogan Mountain, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butler, R. The Tourism Area Life Cycle; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Equation | Equation Explanation | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest neighbor index | NNI is the nearest neighbor distance; is the expected average distance of the nearest neighbor; is the observed average distance; and n is the quantity of the samples. | The nearest neighbor index was used to study the distribution and evolution of the hotel industry. The study sample is concentrated when NNI < 1; when NNI > 1, the study sample is discretely distributed; and when NNI = 1, the study sample is randomly distributed. The likelihood of the study sample being randomly distributed increases as NNI approaches 1 [40]. | |

| Getis–Ord statistic | , | is the agglomeration; is the coordinates of the hotel point j; n is the total number of hotels; and is the spatial weight matrix. | The greater the value, the more aggregated it becomes. Based on the values, the spatial distribution of hotels is classified into four types using the natural breakpoint method: cold spots, sub-cold spots, sub-hot spots, and hot spots [45]. |

| Standard Deviational Ellipse (SDE) | is the short axis; is the long axis; and represent the coordinates of the element ; ) is its center; and n is the number of the element i. | The smaller the , the more pronounced the concentrated distribution of the matter. The greater the difference between and , the more eminent the directionality of the distribution of the matters [46]. |

| Year | Numbers | Average Nearest Neighbor Index (km) | Theoretical Average Nearest Neighbor Distance (km) | Average Nearest Neighbor Index | Z Scores | Distribution Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 31 | 34.408 | 4.852 | 7.09 | 30.827 | Random state |

| 2010 | 535 | 13.199 | 53.674 | 0.245 | −33.491 | Agglomeration state |

| 2019 | 1037 | 9.125 | 47.338 | 0.192 | −49.705 | Agglomeration state |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, X.; Tan, J.; Zhang, J. Spatial–Temporal Correlation between the Tourist Hotel Industry and Town Spatial Morphology: The Case of Phoenix Ancient Town, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710577

Ma X, Tan J, Zhang J. Spatial–Temporal Correlation between the Tourist Hotel Industry and Town Spatial Morphology: The Case of Phoenix Ancient Town, China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710577

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Xuefeng, Jiaxin Tan, and Jiekuan Zhang. 2022. "Spatial–Temporal Correlation between the Tourist Hotel Industry and Town Spatial Morphology: The Case of Phoenix Ancient Town, China" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710577

APA StyleMa, X., Tan, J., & Zhang, J. (2022). Spatial–Temporal Correlation between the Tourist Hotel Industry and Town Spatial Morphology: The Case of Phoenix Ancient Town, China. Sustainability, 14(17), 10577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710577