Creating Shared Value: Exploration in an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What is considered shared value creation in organizations?

- What is considered shared value creation in organizations in an entrepreneurial ecosystem?

- What are the consequences for organizations in an entrepreneurial ecosystem of creating shared value?

- What influence does society have on the activities of companies in the entrepreneurial ecosystem?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Creating Shared Value

2.2. Value Creation in an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

3. Methodology

3.1. Theoretical Sampling and Data Collection

3.2. Procedures for Data Analysis

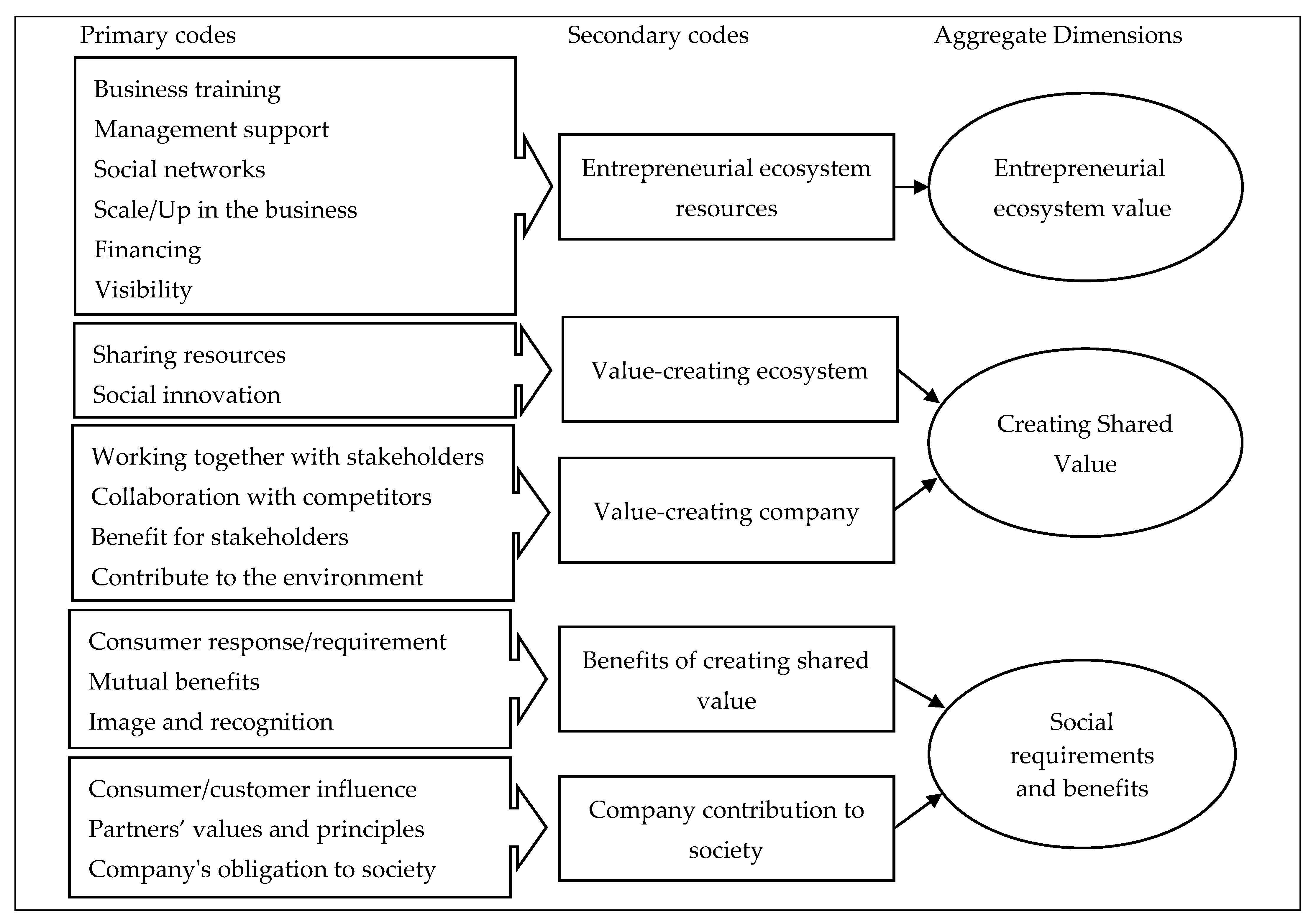

4. Findings

4.1. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Value

Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Resources

“…having that great backing behind you and certainly for me what is most important is the entrepreneurial ecosystem among the entrepreneurs that I’m sure they have told you that as well”.(Timpers, P. 18)

“…brings above all two things that are very important: training and dedication of the professionals who are there”.(ParkUp, P. 16)

“…it trains us not only in aspects of the company itself, in how to configure ourselves, our management, our marketing strategies, sales, operation, etc., it gives us training in other aspects and it is also an ecosystem of proximity to look for this network of clients”.(Booboo, P. 9)

“…well we give them a free training program, we give them visibility, we give them contacts and networking”.(Informant, P. 5)

“…In the professional way they also communicate or link you with many other companies that you could do individually, but it will take you more time”.(Refixme, P. 19)

“…for me what is most important is the business ecosystem among entrepreneurs, it is that everything there is like a big family, even if there are companies there that are dedicated to the same thing as yours, there is no competition”.(Timpers, P. 18)

“The support we have received from them is to a large extent to achieve that scalability, which is not provided by money but by having a firm company structure, a way of working in a more organized way”.(Gana energía, P. 13)

“…We have been able to appear in the press, we have been able to hold talks, organizations, events that, perhaps, probably almost certainly if we were not in Lanzadera would not have been possible”.(Gana energía, P. 13)

4.2. Creating Shared Value

4.2.1. Value-Creating Company

“…we realized the need to digitize the stores and markets, these traditional businesses, because they are gradually losing their sales, because the large platforms and supermarkets are increasingly coping with this demand and we saw that there was a strength in these stores, which is the value of their product”.(BajaBajo, P. 4)

“…within the concept of our business model it is implied that we have to collaborate, that we have to understand each other, that we have to try to improve all the aspects within the ecosystem, not only the customer’s parts, optimizing their flows, their costs, etc. we also help suppliers in the sales consolidation part, we are business capturers for them, and we also optimize their supply chains”.(Booboo, P. 33)

“…despite the fact that everyone defends their own interests, there are certain aspects in which you cannot wage war on your own and I think we should all join together to achieve certain common objectives regardless of the fact that each one defends his own”.(Timpers, P. 40)

“…we make healthy food, and also that healthy food is sustainable. For us, health comes first, it is our focus, then sustainability, because of the intrinsic values of our products, and because they are plant-based, we are helping to solve an ethical problem”.(Vegaly, P. 26)

“…well, right now a psychologist has a lot of unemployment, I think because there is a very small market of people who can afford it. What we want is to open it up, i.e., if you lower the cost it will happen as it has happened in other things, you will have access to more people who will be able to access these services”.(Serenmind, P. 34)

“…So what we want is... we seek the inclusion and normalization of disability and of people with disabilities in the labor market, therefore, we want to give jobs to people with disabilities, we also collaborate with athletes, paralympians and people with some kind of disability with whom we also want to grow hand in hand”.(Timpers, P. 14)

“…we were aware of the law that was passed this year, banning single-use consumer plastic, so we wanted to find a product that we could use to replace plastic but still be sustainable and effective for restaurants and establishments”.(Ecogloop, P. 8)

“…the environmental aspects, because in the end we reduce routes and optimize loads, so this has a much lower energy consumption, which also favors us”.(Booboo, P. 33)

4.2.2. Value-Creating Ecosystem

“…You go with another and you can easily communicate with the company you want, it’s... it’s really wonderful. And on the other hand, at the moment of making synergies, we also said...well, if we are already here and we are helping each other with the business model, logistics and operations with many people, we are going to make synergies between us and between them”.(Refixme, P. 20)

“…each one has knowledge of “I don’t know”… of computer issues, shipping. Well, if we could see the whole issue of shipping packages, we could reduce costs. I know it is complicated because each company has its own shipping strategy, but I think you can share a lot of resources”.(Neki, P. 46)

“…Lanzadera in Valencia has a lot of strength, in the end, what they transmit to us is their management model... these total quality models involve all the actors of what is understood to be a social or entrepreneurial ecosystem”.(Booboo, P. 13)

“…yes, I think so, there are also social projects in Lanzadera that also do very interesting things. It is true that these types of projects are still rarely seen today, there are countries where I think they are more evolved, but in Lanzadera there are some more social projects”.(Timpers, P. 46)

4.3. Social Requirements and Benefits

4.3.1. Benefits of Creating Shared Value

“…it can benefit first in empathy or in the synergy you make with other customers because if there are many customers looking for those values as a whole if I care about sustainability in my daily life where I recycle, I do not promote flash fashion and this company matches my values, then it is a company that will reach me or that will go with me through life”.(Refixme, P. 38)

“…Today, there are more and more companies that are already looking at the level of service and within the level of service they look at environmental aspects, that is to say, that things can be done well and can be done with resources that consume less, and then the price, we will see if there is a big difference, then maybe there will be some companies that will think about it”.(Booboo, P. 34)

“…there are so many companies with situations so similar to yours, with the same problems, with the same concerns, which in the end are always created… that is, is a society that aims to help others, and if I get out of trouble, you get out of trouble”.(ParkUp, P. 10)

“…a win-win where there is no disproportionate win for any party, in general a win-win always benefits everyone”.(Neki, P. 42)

“…we have a central axis that people directly see us as someone who does a very big human and social project… we make sneakers, but if defending the same ideas, the same accessibility, the same line of principles we had made T-shirts, I think it would have gone just as well but precisely because what people like about us is the whole experience, the value we bring”.(Timpers, P. 26)

“…if you take better care of your society and that includes all your suppliers, your partners, your workers, then in the end all this generates an environment that is likely to help you grow. I believe that companies are becoming aware of this and little by little they are changing and are seeing that more and more people are reading about these issues in the newspaper”.(Serenmind, P. 38)

4.3.2. Business as a Contribution to Society and Environment

“…It is not an obligation, so far it is not, but the market tends to value this more and more. To value this social involvement as a contribution of value. We see it in all the big companies that are becoming more and more they are becoming more and more aware of the importance of social involvement as a value contribution”.(BajaBajo, P. 29)

“…Today, either you act right or they will look for an option other than you. So, at the end of the day it is a moral obligation, so to speak in terms of values, but I also think it is an obligation because in the long run companies that do not apply this story, I do not know to what extent they will survive”.(Gana energía, P. 45)

“…we don’t do it to make a profit, we do it because we want to create value. I don’t do it because I think I can benefit from it, I do it because I think the world can benefit from it”.(Vegaly, P. 46)

“…that is what we have opted for and it benefits us at the company level, but also at the personal level of self-satisfaction. To be doing something that goes beyond just a business”.(Ecogloop, P. 32)

“…if you bring some values to your company and that is really reflected in the company, not that you just make a campaign to make it look like you are doing it, but that you are really doing it”.(Serenmind, P. 38)

“…it must go hand in hand with the companies, but also with the governments. I believe that the companies need to be much more concerned and so do the governments and in the end, regulating it also makes the companies care more about it and us”.(Ecogloop, P. 48)

“…the only problem is that we are governed by a type of philosophy that was implemented in the 80’s and is changing, because there, like everything else, there are companies that realize it before”.(Serenmind, P. 38)

5. Discussion and Proposals

5.1. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem, Trainer of Professionals and Creator of Social Networks

5.2. Creating Shared Value

5.3. Value Creation in an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

5.4. Benefits of Shared Value Creation

5.5. Obligations of Companies to Society and Environment

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Research Question | Questions |

|---|---|

| How does the business work and how does it relate to the CE in which participates the company? |

|

| Do you know what it means to create value and how your company develops it? |

|

| Do you know the concept of shared value creation? Is it applied in the development of your business? In what way? |

|

References

- Van den Berghe, L.; Louche, C. The Link between Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility in Insurance. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur. Issues Pract. 2005, 30, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szmigin, I.; Rutherford, R. Shared Value and the Impartial Spectator Test. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Álvarez, I.; Quina-Custodio, I.A. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting and Varieties of Capitalism: An International Analysis of State-led and Liberal Market Economies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sila, I.; Cek, K. The Impact of Environmental, Social and Governance Dimensions of Corporate Social Responsibility on Economic Performance: Australian Evidence. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 120, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Liedtka, J. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Critical Approach. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, O.A.; Mmutle, T. Corporate Reputation through Strategic Communication of Corporate Social Responsibility. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2020, 26, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M.; Schultz, M. Corporate Social Responsibility Communication: Stakeholder Information, Response and Involvement Strategies. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Big Idea: Creating Shared Value. How to Reinvent Capitalism—And Unleash a Wave of Innovation and Growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spence, L.J.; Matten, D. Contesting the Value of “Creating Shared Value. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembek, K.; Singh, P.; Bhakoo, V. Literature Review of Shared Value: A Theoretical Concept or a Management Buzzword? J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 231–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, L.; Scagnelli, S.D.; Mio, C. Simulacra and Sustainability Disclosure: Analysis of the Interpretative Models of Creating Shared Value. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 414–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, P. How Creating Shared Value Differs from Corporate Social Responsibility. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 24, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, A.T. Interfirm Knowledge Exchanges and the Knowledge Creation Capability of Clusters. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 658–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liela, E.; Zeibote, Z.; Stale, L. Business Clusters for Improving Competitiveness and Innovation of Enterprises—Experience of Latvia. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 3, 658–676. [Google Scholar]

- Anh, P.T.; My Dieu, T.T.; Mol, A.P.J.; Kroeze, C.; Bush, S.R. Towards Eco-Agro Industrial Clusters in Aquatic Production: The Case of Shrimp Processing Industry in Vietnam. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 2107–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.; Miyata, Y. Assessing Collective Firm Behavior: Comparing Industrial Symbiosis with Possible Alternatives for Individual Companies in Oahu, HI. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2011, 20, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, F.G.; Belfanti, F. Creating Shared Value and Clusters: The Case of an Italian Cluster Initiative in Food Waste Prevention. Compet. Rev. 2019, 29, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Moon, J.; Cho, J.; Kang, H.-G.; Jeong, J. From Corporate Social Responsibility to Creating Shared Value with Suppliers through Mutual Firm Foundation in the Korean Bakery Industry: A Case Study of the SPC Group. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2014, 20, 461–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, J.; Font, X.; Ivanova, M. Creating Shared Value in Destination Management Organisations: The Case of Turisme de Barcelona. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collazzo, P.; Kubelka, L. Shared Value Clusters in Austria. Compet. Rev. 2019, 29, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno Casanova, G. Análisis y Repercusión de las Lanzaderas de Startups en España como Factor de Éxito Para las Mismas; Universitat Politècnica de València: Valencia, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, J.; Sağsan, M. Impact of Knowledge Management Practices on Green Innovation and Corporate Sustainable Development: A Structural Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.G.; Schaltegger, S. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: A Systematic Review of Architectures. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Baek, W.; Byon, K.K.; Ju, S. Creating Shared Value and Fan Loyalty in the Korean Professional Volleyball Team. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazer, A.; Kanniainen, V.; Poutvaara, P. Firms’ Ethics, Consumer Boycotts, and Signalling. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2008, 26, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, K. The Case for and Against Business Assumption of Social Responsibilities. Acad. Manag. J. 1973, 16, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V. Corporate Social Responsibility. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmitz, J.; Schrader, J. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Microeconomic Review of the Literature. J. Econ. Surv. 2015, 29, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing Better at Doing Good: When, Why, and How Consumers Respond to Corporate Social Initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creyer, E.H. The Influence of Firm Behavior on Purchase Intention: Do Consumers Really Care about Business Ethics? J. Consum. Mark. 1997, 14, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.D.; Faff, R.W.; Langfield-Smith, K. Revisiting the Vexing Question: Does Superior Corporate Social Performance Lead to Improved Financial Performance? Aust. J. Manag. 2009, 34, 21–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, A.; Mackey, T.B.; Barney, J.B. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firm Performance: Investor Preferences and Corporate Strategies. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 817–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhamme, J.; Grobben, B. “Too Good to Be True!”. The Effectiveness of CSR History in Countering Negative Publicity. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 85, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Institutional Analysis and the Paradox of Corporate Social Responsibility. Am. Behav. Sci. 2006, 49, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, W.S. Social Accountability and Corporate Greenwashing. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.P.; Schepers, D.H. United Nations Global Compact: The Promise–Performance Gap. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, B. Corporate Social Responsibility in International Development: An Overview and Critique. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2003, 10, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedman, M. A Theoretical Framework for Monetary Analysis. J. Polit. Econ. 1970, 78, 193–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatterjee, B. Business and Communities-Redefining Boundaries. NHRD Netw. J. 2012, 5, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.-J.; Hwang, H. What Makes Consumers Respond to Creating Shared Value Strategy? Considering Consumers as Stakeholders in Sustainable Development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fearne, A.; Garcia Martinez, M.; Dent, B. Dimensions of Sustainable Value Chains: Implications for Value Chain Analysis. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzeck, H.; Chapman, S. Creating Shared Value as a Differentiation Strategy—The Example of BASF in Brazil. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2012, 12, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grönroos, C.; Ravald, A. Service as Business Logic: Implications for Value Creation and Marketing. J. Serv. Manag. 2011, 22, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L.; O’Brien, M. Competing through Service: Insights from Service-Dominant Logic. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, D.; Varey, R.J. Creating Value-in-Use through Marketing Interaction: The Exchange Logic of Relating, Communicating and Knowing. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinonen, K.; Strandvik, T.; Mickelsson, K.; Edvardsson, B.; Sundström, E.; Andersson, P. A Customer-dominant Logic of Service. J. Serv. Manag. 2010, 21, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos-Cuevas, J.; Nätti, S.; Palo, T.; Baumann, J. Value Co-Creation Practices and Capabilities: Sustained Purposeful Engagement across B2B Systems. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 56, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gouillart, F. Experience Co-Creation. Available online: https://hbr.org/2011/04/experience-co-creation (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Vorbach, S.; Müller, C.; Poandl, E. Co-Creation of Value Proposition: Stakeholders Co-Creating Value Propositions of Goods and Services. In Co-Creation. Management for Professionals; Redlich, T., Moritz, M., Wulfsberg, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Maglio, P.P.; Akaka, M.A. On Value and Value Co-Creation: A Service Systems and Service Logic Perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 2008, 26, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, E. Exit Services Marketing—Enter Service Marketing. J. Cust. Behav. 2007, 6, 113–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, G. Industrial Networks: A Review. In Industrial Networks: A New View of Reality; Axelsson, B., Easton, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1992; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nätti, S.; Pekkarinen, S.; Hartikka, A.; Holappa, T. The Intermediator Role in Value Co-Creation within a Triadic Business Service Relationship. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gamez, M.A.; Gutierrez-Ruiz, A.M.; Becerra-Vicario, R.; Ruiz-Palomo, D. The Effects of Creating Shared Value on the Hotel Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aravossis, K.; Pavlopoulou, Y. Creating Shared Value with Eco-Efficient and Green Chemical Systems in Ship Operations and in Ballast Water Management. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2013, 22, 3880–3888. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Global Economy. Econ. Dev. Q. 2000, 14, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, F.G.; Pizzurno, E. Knowledge Exchanges in Innovation Networks: Evidences from an Italian Aerospace Cluster. Compet. Rev. 2015, 25, 258–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.J.; Tracey, P.; Heide, J.B. The Organization of Regional Clusters. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2009, 34, 623–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J.; Voola, R. Knowledge Integration and Competitiveness: A Longitudinal Study of an Industry Cluster. J. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 17, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Porter, M.E.; Stern, S. Defining Clusters of Related Industries. J. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 16, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, O.; Audia, P.G. The Social Structure of Entrepreneurial Activity: Geographic Concentration of Footwear Production in the United States, 1940–1989. Am. J. Sociol. 2000, 106, 424–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adner, R. Ecosystem as Structure: An Actionable Construct for Strategy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E.; Spigel, B. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. In The SAGE Handbook of Small Business and Entrepreneurship; Blackburn, R., De Clercq, D., Heinonen, J., Eds.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2018; pp. 407–421. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.; Mason, C. Looking inside the Spiky Bits: A Critical Review and Conceptualisation of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooke, P.; Gomez Uranga, M.; Etxebarria, G. Regional Innovation Systems: Institutional and Organisational Dimensions. Res. Policy 1997, 26, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Porter, M.E.; Stern, S. Clusters and Entrepreneurship. J. Econ. Geogr. 2010, 10, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Kerr, W.R. Local Industrial Conditions and Entrepreneurship: How Much of the Spatial Distribution Can We Explain? J. Econ. Manag. Strateg. 2009, 18, 623–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neffke, F.; Henning, M.; Boschma, R. How Do Regions Diversify over Time? Industry Relatedness and the Development of New Growth Paths in Regions. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 87, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Peña-Legazkue, I. Entrepreneurial Activity and Regional Competitiveness: An Introduction to the Special Issue. Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 39, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Brown, R. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Growth Oriented Entrepreneurship. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/Entrepreneurial-ecosystems.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Tsvetkova, A. Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Metropolitan Economic Performance: Empirical Test of Recent Theoretical Propositions. Econ. Dev. Q. 2015, 29, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, F.G.; Belfanti, F. Do Clusters Create Shared Value? A Social Network Analysis of the Motor Valley Case. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2020, 31, 326–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Thomsen, P.; Pillay, R.G. CSR in Industrial Clusters: An Overview of the Literature. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2012, 12, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzadri, A. Indian Garment Clusters and CSR Norms: Incompatible Agendas at the Bottom of the Garment Commodity Chain. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2014, 42, 238–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Thomsen, P.; Nadvi, K. Clusters, Chains and Compliance: Corporate Social Responsibility and Governance in Football Manufacturing in South Asia. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsé, M.; Sierra, M.; Roig, O. Generating Shared Value through Clusters. Living Examples in Catalonia/Generando Valor Compartido a Través de Clusters. Ejemplos Vivientes En Cataluña; ACCIÓ: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, W.; Lavie, D.; Reuer, J.J.; Shipilov, A. The Interplay of Competition and Cooperation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 3033–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, H.; Snehota, I. Developing Relationships in Business Networks; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S.D.; Lambe, C.J.; Wittmann, C.M. A Theory and Model of Business Alliance Success. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2002, 1, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Strotmann, H. Absorptive Capacity and Innovation in the Knowledge Intensive Business Service Sector. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2008, 17, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, L. Cooperating for Survival: Tannery Pollution and Joint Action in the Palar Valley (India). World Dev. 1999, 27, 1673–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrobelli, C.; Stevenson, C. Cluster Development Programs in Latin America and the Caribbean: Lessons from the Experience of the Inter-American Development Bank; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Báez, J.; de Tudela, P. Fundamentos de La Investigación Cualitativa. In Métodos de investigación Social y de la Empresa; Sarabia Sánchez, F.J., Ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 525–553. [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda, G.; Martin, D. A Review of Case Studies Publishing in Management Decision 2003–2004: Guides and Criteria for Achieving Quality in Qualitative Research. Manag. Decis. 2005, 43, 851–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siggelkow, N. Persuasion With Case Studies. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, W.G.; Wilkins, A.L. Better Stories, Not Better Constructs, To Generate Better Theory: A Rejoinder to Eisenhardt. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, J. Building Operations Management Theory through Case and Field Research. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 16, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runeson, P.; Höst, M. Guidelines for Conducting and Reporting Case Study Research in Software Engineering. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2008, 14, 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, R.K. Validity and Generalization in Future Case Study Evaluations. Evaluation 2013, 19, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nogales, A.F. La Entrevista En Profundidad. In Métodos de Investigación Social y de la Empresa; Sarabia Sánchez, F.J., Ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2013; pp. 575–599. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.-M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic Methodological Review: Developing a Framework for a Qualitative Semi-Structured Interview Guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louise Barriball, K.; While, A. Collecting Data Using a Semi-Structured Interview: A Discussion Paper. J. Adv. Nurs. 1994, 19, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss, S.E.; Hamzah, A.; Omar, Z.; Suandi, T.; Ismail, I.A.; Zahari, M.Z.; Nor, Z.M. Preliminary Investigation and Interview Guide Development for Studying How Malaysian Farmers’ Form Their Mental Models of Farming. Qual. Rep. 2009, 14, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cridland, E.K.; Jones, S.C.; Caputi, P.; Magee, C.A. Qualitative Research with Families Living with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Recommendations for Conducting Semistructured Interviews. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 40, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turner, D.W. Qualitative Interview Design: A Practical Guide for Novice Investigators. Qualtitative Rep. 2010, 15, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzadera. Folleto-Lanzadera-2017–2018. 2018. Available online: http://lanzadera.es/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/folleto-lanzadera-2017–2018.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Asociación Valenciana de Empresarios. Juan Roig Ha Multiplicado Su Inversión En Lanzadera Hasta Los 10 Millones de Euros para Activar el Ecosistema Emprendedor (Valencian Association of Entrepreneurs. Juan Roig Has Multiplied His Investment In Lanzadera To 10 Million Euros To Activate The Entrepreneurial Ecosystem). Available online: https://www.ave.org.es/2020/05/juan-roig-ha-multiplicado-su-inversion-en-lanzadera-hasta-los-10-millones-de-euros-para-activar-el-ecosistema-emprendedor/ (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Lanzadera Aceleradora e Incubadora de Empresas—Lanzadera. Available online: https://lanzadera.es/ (accessed on 16 January 2020).

- ABC. Estas Son Las Cien Nuevas Startups Que Se Incorporan a La Lanzadera de Juan Roig. Available online: https://www.abc.es/espana/comunidad-valenciana/abci-estas-cien-nuevas-startups-incorporan-lanzadera-juan-roig-202109061110_noticia.html (accessed on 21 June 2022).

- Piekkari, R.; Plakoyiannaki, E.; Welch, C. ‘Good’ Case Research in Industrial Marketing: Insights from Research Practice. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuş Saillard, E. Systematic versus Interpretive Analysis with Two CAQDAS Packages: NVivo and MAXQDA. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2011, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner Researchers; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ács, Z.J.; Autio, E.; Szerb, L. National Systems of Entrepreneurship: Measurement Issues and Policy Implications. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-L.; Hsu, M.-S.; Lin, F.-J.; Chen, Y.-M.; Lin, Y.-H. The Effects of Industry Cluster Knowledge Management on Innovation Performance. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, B.; Harrison, R. Toward a Process Theory of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2018, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoang, H.; Antoncic, B. Network-Based Research in Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Geng, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, W. Shared Resources and Competitive Advantage in Clustered Firms: The Missing Link. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2010, 18, 1391–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, R.; Lynn, T.; Mac an Bhaird, C. Individual Level Assessment in Entrepreneurship Education: An Investigation of Theories and Techniques. J. Entrep. Educ. 2015, 18, 136–156. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D.N.; Reboud, S.; Toutain, O.; Ballereau, V.; Mazzarol, T. Entrepreneurial Education: An Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Approach. J. Manag. Organ. 2021, 27, 694–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, P.; Clark, G.L. Alliances, Networks and Competitive Strategy: Rethinking Clusters of Innovation. Growth Change 2003, 34, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.; Levinthal, D. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pontrandolfo, P.; Pujari, D. Developing Sustainable New Products in the Textile and Upholstered Furniture Industries: Role of External Integrative Capabilities. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 642–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga, S. El Modelo de Calidad Total de Mercadona. Available online: https://lanzadera.es/modelo-calidad-total-mercadona/ (accessed on 9 June 2021).

- Van Praag, C.M.; Versloot, P.H. What Is the Value of Entrepreneurship? A Review of Recent Research. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 29, 351–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breschi, S.; Malerba, F. The Geography of Innovation and Economic Clustering: Some Introductory Notes. Ind. Corp. Change 2001, 10, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; de Zubielqui, G.C.; O’Connor, A. Entrepreneurial Networking Capacity of Cluster Firms: A Social Network Perspective on How Shared Resources Enhance Firm Performance. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 45, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanen, H.; Halinen, A.; Jaakkola, E. Accessing Resources for Service Innovation—The Critical Role of Network Relationships. J. Serv. Manag. 2014, 25, 2–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchelmore, S.; Rowley, J. Entrepreneurial Competencies: A Literature Review and Development Agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebbi, A.; Valliere, D. The Double J-Curve: A Model for Incubated Start-Ups. In Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Jyväskylä, Finland, 15–16 September 2016; pp. 371–380. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, L.; Rice, M.; Sundararajan, M. The Role of Incubators in the Entrepreneurial Process. J. Technol. Transf. 2004, 29, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J. Collaborative Networks as Determinants of Knowledge Diffusion Patterns. Manag. Sci. 2005, 51, 756–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kramer, M.R.; Pfitzer, M.W. The Ecosystem of Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 94, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M.; Hornych, C. Cooperation Patterns of Incubator Firms and the Impact of Incubator Specialization: Empirical Evidence from Germany. Technovation 2010, 30, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wang, C. Research on the Co-Evolution of Industrial Cluster Development and Entrepreneur Learning Based on Knowledge Capitalization. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Management of Innovation & Technology, Singapore, 2–5 June 2010; pp. 853–858. [Google Scholar]

- Boccia, F.; Malgeri Manzo, R.; Covino, D. Consumer Behavior and Corporate Social Responsibility: An Evaluation by a Choice Experiment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kates, S.M. The Dynamics of Brand Legitimacy: An Interpretive Study in the Gay Men’s Community. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainability: Consumer Perceptions and Marketing Strategies. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2006, 15, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmann, C.; Fichter, K.; Klofsten, M.; Audretsch, D.B. Sustainable Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: An Emerging Field of Research. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigors, M.; Rockenbach, B. Consumer Social Responsibility. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 3123–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lai, I.K.W. The Ethical Judgment and Moral Reaction to the Product-Harm Crisis: Theoretical Model and Empirical Research. Sustainability 2016, 8, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Company | Informant Role | Company’s Activity | Years of Business | Countries Where It Participates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ParkUp | Founder | Parking management | 6 | Spain |

| Booboo | Founder | Transportation and logistics optimization | 3 | Spain |

| Gana Energía | Marketing Manager | Energy distributor | 5 | Spain |

| Serenmind | Founder | Psychological treatments | 2 | Spain |

| Neki | Founder | Safety for seniors | 4 | Spain, Italy, Sweden, and Portugal |

| Timpers | Founder | Footwear | 2 | Spain, France, Netherlands, Italy, Germany, United Kingdom, Mexico, and the U.S. |

| Refixme | Founder | Footwear | 2 | Spain |

| Ecogloop | Founder | Cutlery | 1 | Spain |

| BajaBajoapp | Founder | Logistics | 1 | Spain |

| Vegaly | Founder | Food services | 1 | Spain and Portugal |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Royo-Vela, M.; Cuevas Lizama, J. Creating Shared Value: Exploration in an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148505

Royo-Vela M, Cuevas Lizama J. Creating Shared Value: Exploration in an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148505

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoyo-Vela, Marcelo, and Jonathan Cuevas Lizama. 2022. "Creating Shared Value: Exploration in an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148505

APA StyleRoyo-Vela, M., & Cuevas Lizama, J. (2022). Creating Shared Value: Exploration in an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem. Sustainability, 14(14), 8505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148505