How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced the Tourism Behaviour of International Students in Poland?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

General Overview

2. Literature Review

3. Research Objectives

- What areas of international student tourism behaviour were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic?

- What differences in travel behaviour occurred between international students from Europe and Asia?

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Approval

4.2. Design of Questionnaire

4.3. Study Design and Sample

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Overall Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

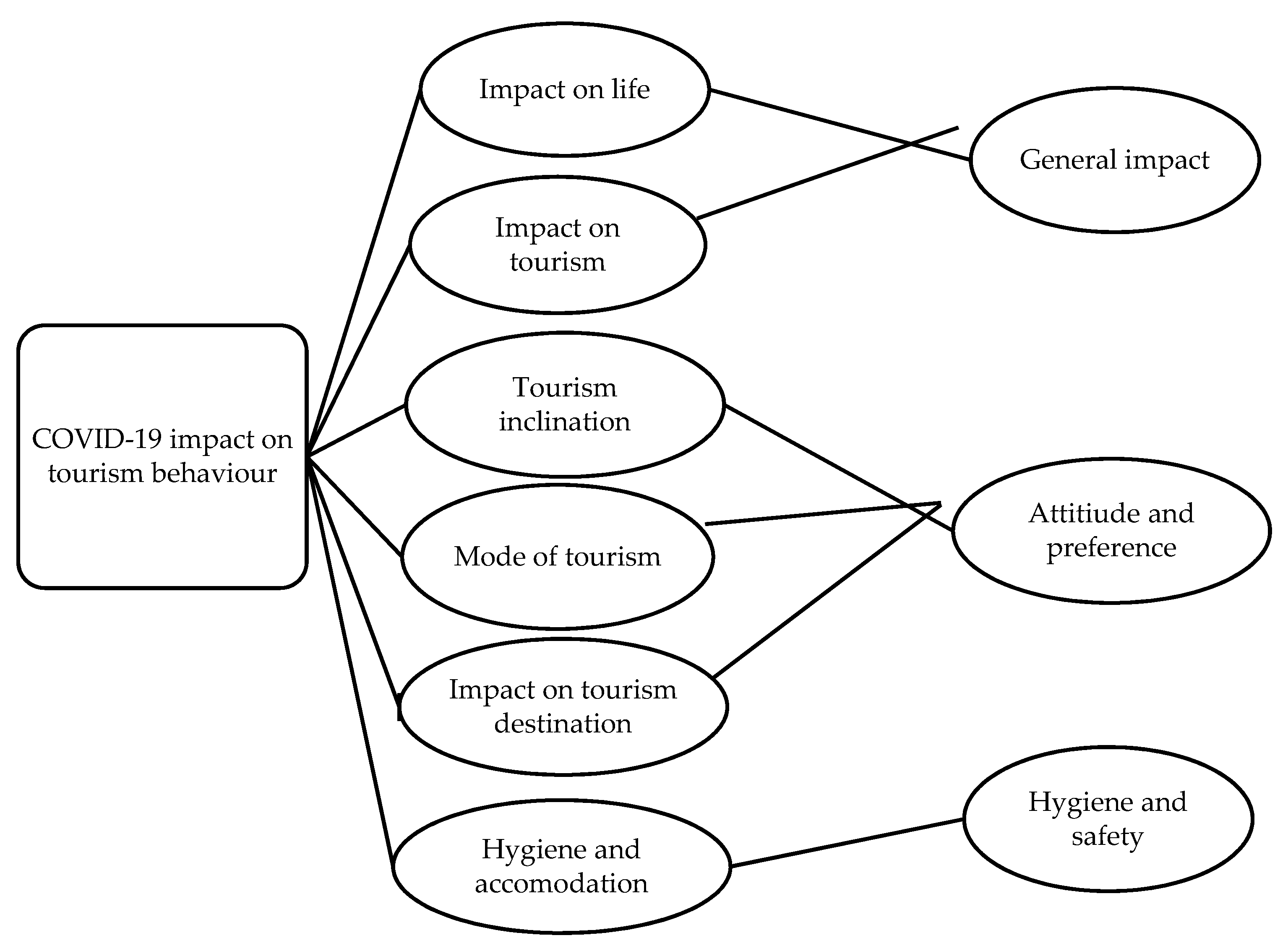

5.2. Explaratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

5.3. Regional Differences in Perceptionsof the Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Some Aspects of Life

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McA Baker, D. Tourism and the Health Effects of Infectious Diseases: Are There Potential Risks for Tourists? Int. J. Saf. Secur. Tour. 2015, 12, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, L.; James, F.; Short, J. Social Organization and Risk: Some Current Controversies. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1993, 19, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Influence of terrorism risk on foreign tourism decisions. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 112–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faulkner, B. Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, T.-C.; Beaman, J.; Shelby, L. No-escape natural disaster Mitigating Impacts on Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Blake, A.; Cooper, C. China’s tourism in a global financial crisis: A computable general equilibrium approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, C.; Fidgeon, P.; John, S.; Page, S.J. Current Issues in Tourism Maritime tourism and terrorism: Customer perceptions of the potential terrorist threat to cruise shipping Maritime tourism and terrorism: Customer perceptions of the potential terrorist threat to cruise shipping. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 610–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, D.; Sharpley, R. Current Issues in Tourism Local community perceptions of disaster tourism: The case of L’Aquila, Italy Local community perceptions of disaster tourism: The case of L’Aquila, Italy. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1569–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Crotts, J.C.; Zehrer, A.; Volsky, G.T. Understanding the Effects of a Tourism Crisis: The Impact of the BP Oil Spill on Regional Lodging Demand. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paraskevas, A.; Altinay, L.; McLean, J.; Cooper, C. Crisis knowledge in tourism: Types, flows and governance. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitroff, I.I. Crisis Management: Cutting Through the Confusion. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1988, 29, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, G. Crisis Management and Tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 15, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vărzaru, A.A.; Bocean, C.G.; Cazacu, M. Rethinking tourism industry in pandemic COVID-19 period. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccloskey, B.; Heymann, D.L. Epidemiology and Infection SARS to novel coronavirus-old lessons and new lessons. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 148, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Horby, P.W.; Hayden, F.G.; Gao, G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020, 395, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Chiew, C.J.; Lee, V.J. Can we contain the COVID-19 outbreak with the same measures as for SARS? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mary, E.; Wilson, L.H.C. Travellers give wings to novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa015. [Google Scholar]

- Bogoch, I.I.; Watts Phd, A.; Thomas-Bachli, A.; Msa, C.H.; Dphil, M.U.G.K.; Khan, K. Potential for global spread of a novel coronavirus from China. J. Travel Med. 2020, 2020, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, T.D.; Ferguson, N.M.; Anderson, R.M. Frequent travelers and rate of spread of epidemics. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grais, R.F.; Hugh Ellis, J.; Glass, G.E. Assessing the impact of airline travel on the geographic spread of pandemic influenza. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 18, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shi, Z.; Yu, M.; Ren, W.; Smith, C.; Epstein, J.H.; Wang, H.; Crameri, G.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Bats Are Natural Reservoirs of SARS-Like Coronaviruses. Science 2005, 310, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Estrada, M.A.; Koutronas, E. The Networks Infection Contagious Diseases Positioning System (NICDP-System): The Case of Wuhan-COVID-19. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3548413. (accessed on 29 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- McKibbin, W.J.; Fernando, R. The Global Macroeconomic Impacts of COVID-19: Seven Scenarios. SSRN Electron. J. 2020, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- How COVID-19 is changing the world: A statistical perspective from the Committee for the Coordination of Statistical activities. Stat. J. IAOS 2020, 36, 851–860. [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Image Formation Process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1994, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beerli, A.; Martín, J.D. Factors influencing destination image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Gartner, W.C.; Cavusgil, S.T. Conceptualization and Operationalization of Destination Image. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2007, 31, 194–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.; Mair, J.; Lim, J. Sensationalist media reporting of disastrous events: Implications for tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 28, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gu, H.; Kavanaugh, R.R. The impacts of SARS on the consumer behaviour of Chinese domestic tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2005, 8, 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Akintunde, T.Y.; Musa, T.H.; Musa, H.H.; Musa, I.H.; Chen, S.; Ibrahim, E.; Tassang, A.E.; Helmy, M.S.E.D.M. Bibliometric analysis of global scientific literature on effects of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2021, 63, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Madrid González, A.; Haegeman, C.; Rainoldi, K. Behavioural Changes in Tourism in Times of COVID-19 Employment Scenarios and Policy Options; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 9789276204015. [Google Scholar]

- Bratić, M.; Radivojević, A.; Stojiljković, N.; Simović, O.; Juvan, E.; Lesjak, M.; Podovšovnik, E. Should i stay or should i go? Tourists’ COVID-19 risk perception and vacation behavior shift. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningrum, D.A.; Wachyuni, S.S. The Shifting Trends in Travelling After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Rev. 2020, 7, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council, T.; Wyman, O. To Recovery & Beyond: The Future of Travel & Tourism in the Wake of COVID-19. World Travel Tour. Counc. 2020, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.; Dias, C.; Muley, D.; Shahin, M. Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on travel behavior and mode preferences. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect 2020, 8, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, M.Z.; Belgiawan, P.F.; Joewono, T.B.; Bastarianto, F.F.; Rizki, M.; Ilahi, A. Exploring activity-travel behavior changes during the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Transportation 2022, 49, 529–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Seyfi, S.; Rastegar, R.; Hall, C.M. Destination image during the COVID-19 pandemic and future travel behavior: The moderating role of past experience. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 2212–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Jamaludin, A.; Zuraimi, N.S.M.; Valeri, M. Visit intention and destination image in post-COVID-19 crisis recovery. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 2392–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.; Dias, F.; de Araújo, A.F.; Andrés Marques, M.I. A destination imagery processing model: Structural differences between dream and favourite destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.H.; Kim, S.S.; Elliot, S.; Han, H. Conceptualizing Destination Brand Equity Dimensions from a Consumer-Based Brand Equity Perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A.; Amin, I. Can customer based brand equity help destinations to stay in race? An empirical study of Kashmir valley. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 23, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarelli, A. Unraveling the complexity of “city brand equity”: A three-dimensional framework. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2012, 5, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska-Warsewicz, H. Factors determining city brand equity-A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Bao, J.; Tang, C. Profiling and evaluating Chinese consumers regarding post-COVID-19 travel. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 25, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemli, S.; Toanoglou, M.; Valeri, M. The impact of COVID-19 media coverage on tourist’s awareness for future travelling. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Duan, Y.; Ali, L.; Duan, Y.; Ryu, K. Understanding consumer travel behavior during covid-19. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuburger, L.; Egger, R. Travel risk perception and travel behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020: A case study of the DACH region. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, C.Y.; Yang, H.W. The structural changes of a local tourism network: Comparison of before and after COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3324–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.K.; Gazi, A.I.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Rahaman, A. Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on tourist travel risk and management perceptions. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 719 | (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 331 | 46.0 |

| Male | 388 | 54.0 |

| Age | ||

| 18–26 | 393 | 54.7 |

| 27–34 | 106 | 14.7 |

| 35 and above | 220 | 30.6 |

| Working shifts | ||

| No | 264 | 36.7 |

| Yes | 455 | 63.3 |

| Financial situation | ||

| I have enough money for everything without special savings | 248 | 34.5 |

| I live sparingly and have enough money for my basic needs | 333 | 46.3 |

| I live very sparingly to put aside money for my secondary needs | 107 | 14.9 |

| I do not have enough money for my basic needs (such as food and clothes) | 31 | 4.3 |

| Region | ||

| Europe | 286 | 39.8 |

| Asia | 369 | 51.3 |

| Other | 64 | 8.9 |

| Items | Mean *; SD | Median (Minimum–Maximum) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General impact | COVID-19 has a great impact on my work and life | 4.20 ± 1.140 | 5 ** (1–5) |

| COVID-19 has a great impact on my way of life | 4.04 ± 1.136 | 4 ** (1–5) | |

| All of my business travels have been cancelled during the COVID-19 period | 4.17 ± 1.186 | 5 ** (1–5) | |

| All of my leisure travels have been cancelled during the COVID-19 period | 4.31 ± 1.041 | 5 ** (1–5) | |

| Attitude and preference | Because of COVID-19, my interest in participating in eco-tourism has increased | 3.54 ± 1.287 | 4 ** (1–5) |

| Because of COVID-19, my interest in participating in outdoor activities has increased | 3.52 ± 1.327 | 4 ** (1–5) | |

| I will definitely reduce my travel plans in the next 12 months | 3.72 ± 1.386 | 4 ** (1–5) | |

| I will avoid travelling to crowded big cities after COVID-19 finishes | 3.57 ± 1.396 | 4 ** (1–5) | |

| I will reduce the length of travel and tourism after the COVID-19 period | 3.57 ± 1.339 | 4 ** (1–5) | |

| In choosing tourist destinations, I will avoid COVID-19-affected areas | 3.96 ± 1.199 | 4 ** (1–5) | |

| I will not take any travel activities till the next travel season after the COVID-19 period | 3.18 ± 1.443 | 3 ** (1–5) | |

| I prefer suburbs or areas within short distance for leisure travel after the COVID-19 period | 3.76 ± 1.170 | 4 ** (1–5) | |

| I will reduce the possibility of joining tour groups after the COVID-19 period | 3.76 ± 1.188 | 4 ** (1–5) | |

| I prefer travelling with family members and relatives after the COVID-19 period | 3.80 ± 1.238 | 4 ** (1–5) | |

| I will travel more around the country after the COVID-19 period | 3.50 ± 1.286 | 4 ** (1–5) | |

| I will travel more abroad after the COVID-19 period | 3.18 ± 1.321 | 3 ** (1–5) | |

| Hygiene and safety | I care more about the hygiene and safety of the tourist sites during the COVID-19 period | 4.35 ± 0.982 | 5 ** (1–5) |

| I care more about the hygiene and safety of the daily necessities while travelling after the COVID-19 period | 4.24 ± 1.016 | 5 ** (1–5) | |

| I care more about the hygiene and safety of the public recreation sites after the COVID-19 period | 4.30 ± 0.994 | 5 ** (1–5) | |

| I prefer to stay in high-quality, five-star hotels after the COVID-19 period | 3.58 ± 1.293 | 4 ** (1–5) |

| Items | Impact on Life | Impact on Tourism | Tourism Inclination | Mode of tourism | Impact on Tourist Destination | Hygiene and Accommodation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General impact | COVID-19 has a great impact on my work and life | 0.825 | |||||

| COVID-19 has a great impact on my way of life | 0.875 | ||||||

| All of my business travels have been cancelled during the COVID-19 period | −0.608 | ||||||

| All of my leisure travels have been cancelled during the COVID-19 period | −0.590 | ||||||

| Attitude and preference | Because of COVID-19, my interest in participating in eco-tourism has increased | −0.770 | |||||

| Because of COVID-19, my interest in participating in outdoor activities has increased | −0.590 | ||||||

| I will definitely reduce my travel plans in the next 12 months | 0.589 | ||||||

| I will avoid travelling to crowded big cities after COVID-19 finishes | 0.744 | ||||||

| I will reduce the length of travel and tourism after the COVID-19 period | 0.647 | ||||||

| In choosing tourist destinations, I will avoid COVID-19-affected areas | 0.545 | ||||||

| I will not take any travel activities till the next travel season after the COVID-19 period | 0.806 | ||||||

| I prefer suburbs or areas within short distance for leisure travel after the COVID-19 period | 0.615 | ||||||

| I will reduce the possibility of joining tour groups after the COVID-19 period | 0.565 | ||||||

| I prefer travelling with family members and relatives after the COVID-19 period | 0.843 | ||||||

| I will travel more around the country after the COVID-19 period | 0.827 | ||||||

| I will travel more abroad after the COVID-19 period | 0.833 | ||||||

| Hygiene and safety | I care more about the hygiene and safety of the tourist sites during the COVID-19 period | −0.792 | |||||

| I care more about the hygiene and safety of the daily necessities while travelling after the COVID-19 period | −0.838 | ||||||

| I care more about the hygiene and safety of the public recreation sites after the COVID-19 period | −0.792 | ||||||

| I prefer to stay in high-quality, five-star hotels after the COVID-19 period | −0.508 | ||||||

| Variance explained (%) | 7.60% | 6.42% | 29.10% | 5.07% | 10.45% | 7.90% | |

| Total variance explained | 66.58% | ||||||

| Items | Region | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | Asia | Others | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| General impact | COVID-19 has a great impact on my work and life * | 3.86 a ± 1.32 | 4.53 ab ± 0.83 | 3.83 b ± 1.29 | |||

| COVID-19 has a great impact on my way of life * | 3.60 ab ± 1.29 | 4.35 a ± 0.86 | 4.23 b ± 1.21 | ||||

| All of my business travels have been cancelled during the COVID-19 period * | 3.88 ab ± 1.34 | 4.38 a ± 0.97 | 4.19 ± 1.31 | ||||

| All of my leisure travels have been cancelled during the COVID-19 period * | 4.11 a ± 1.20 | 4.48 a ± 0.83 | 4.17 ± 1.20 | ||||

| Attitude and preference | Because of COVID-19, my interest in participating in eco-tourism has increased | 3.41 ± 1.34 | 3.65 ± 1.22 | 3.50 ± 1.40 | |||

| Because of COVID-19, my interest in participating in outdoor activities has increased | 3.48 ± 1.22 | 3.55 ± 1.37 | 3.52 ± 1.53 | ||||

| I will definitely reduce my travel plans in the next 12 months * | 3.31 ab ± 1.47 | 4.01 a ± 1.21 | 3.87 b ± 1.48 | ||||

| I will avoid travelling to crowded big cities after COVID-19 finishes * | 3.00 ab ± 1.44 | 4.02 ac ± 1.23 | 3.55 bc ± 1.21 | ||||

| I will reduce the length of travel and tourism after the COVID-19 period * | 3.07 a ± 1.33 | 4.02 ab ± 1.16 | 3.23 b ± 1.46 | ||||

| In choosing tourist destinations, I will avoid COVID-19-affected areas * | 3.55 ab ± 1.26 | 4.27 a ± 1.06 | 4.00 b ± 1.16 | ||||

| I will not take any travel activities till the next travel season after the COVID-19 period * | 2.71 ab ± 1.37 | 3.52 a ± 1.39 | 3.27 b ± 1.51 | ||||

| I prefer suburbs or areas within short distance for leisure travel after the COVID-19 period * | 3.40 a ± 1.16 | 4.04 a ± 1.11 | 3.77 ± 1.14 | ||||

| I will reduce the possibility of joining tour groups after the COVID-19 period * | 3.42 ab ± 1.21 | 4.00 a ± 1.13 | 3.91 b ± 1.08 | ||||

| I prefer travelling with family members and relatives after the COVID-19 period * | 3.52 ab ± 1.26 | 3.97 a ± 1.20 | 4.11 b ± 1.24 | ||||

| I will travel more around the country after the COVID-19 period * | 3.32 a ± 1.23 | 3.63 a ± 1.33 | 3.55 ± 1.22 | ||||

| I will travel more abroad after the COVID-19 period | 3.12 ± 1.27 | 3.22 ± 1.39 | 3.23 ± 1.12 | ||||

| Hygiene andsafety | I care more about the hygiene and safety of the tourist sites during the COVID-19 period * | 4.10 a ± 1.08 | 4.57 a ± 0.79 | 4.20 ± 1.24 | |||

| I care more about the hygiene and safety of the daily necessities while travelling after the COVID-19 period * | 3.99 a ± 1.10 | 4.42 a ± 0.89 | 4.25 ± 1.02 | ||||

| I care more about the hygiene and safety of the public recreation sites after the COVID-19 period * | 4.06 a ± 1.13 | 4.52 ab ± 0.80 | 4.12 b ± 1.06 | ||||

| I prefer to stay in high-quality, five-star hotels after the COVID-19 period * | 3.47 a ± 1.30 | 3.76 ab ± 1.20 | 3.03 b ± 1.54 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szlachciuk, J.; Kulykovets, O.; Dębski, M.; Krawczyk, A.; Górska-Warsewicz, H. How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced the Tourism Behaviour of International Students in Poland? Sustainability 2022, 14, 8480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148480

Szlachciuk J, Kulykovets O, Dębski M, Krawczyk A, Górska-Warsewicz H. How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced the Tourism Behaviour of International Students in Poland? Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148480

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzlachciuk, Julita, Olena Kulykovets, Maciej Dębski, Adriana Krawczyk, and Hanna Górska-Warsewicz. 2022. "How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced the Tourism Behaviour of International Students in Poland?" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148480

APA StyleSzlachciuk, J., Kulykovets, O., Dębski, M., Krawczyk, A., & Górska-Warsewicz, H. (2022). How Has the COVID-19 Pandemic Influenced the Tourism Behaviour of International Students in Poland? Sustainability, 14(14), 8480. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148480