Cooperative Organization and Its Characteristics in Economic and Social Development (1995 to 2020)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

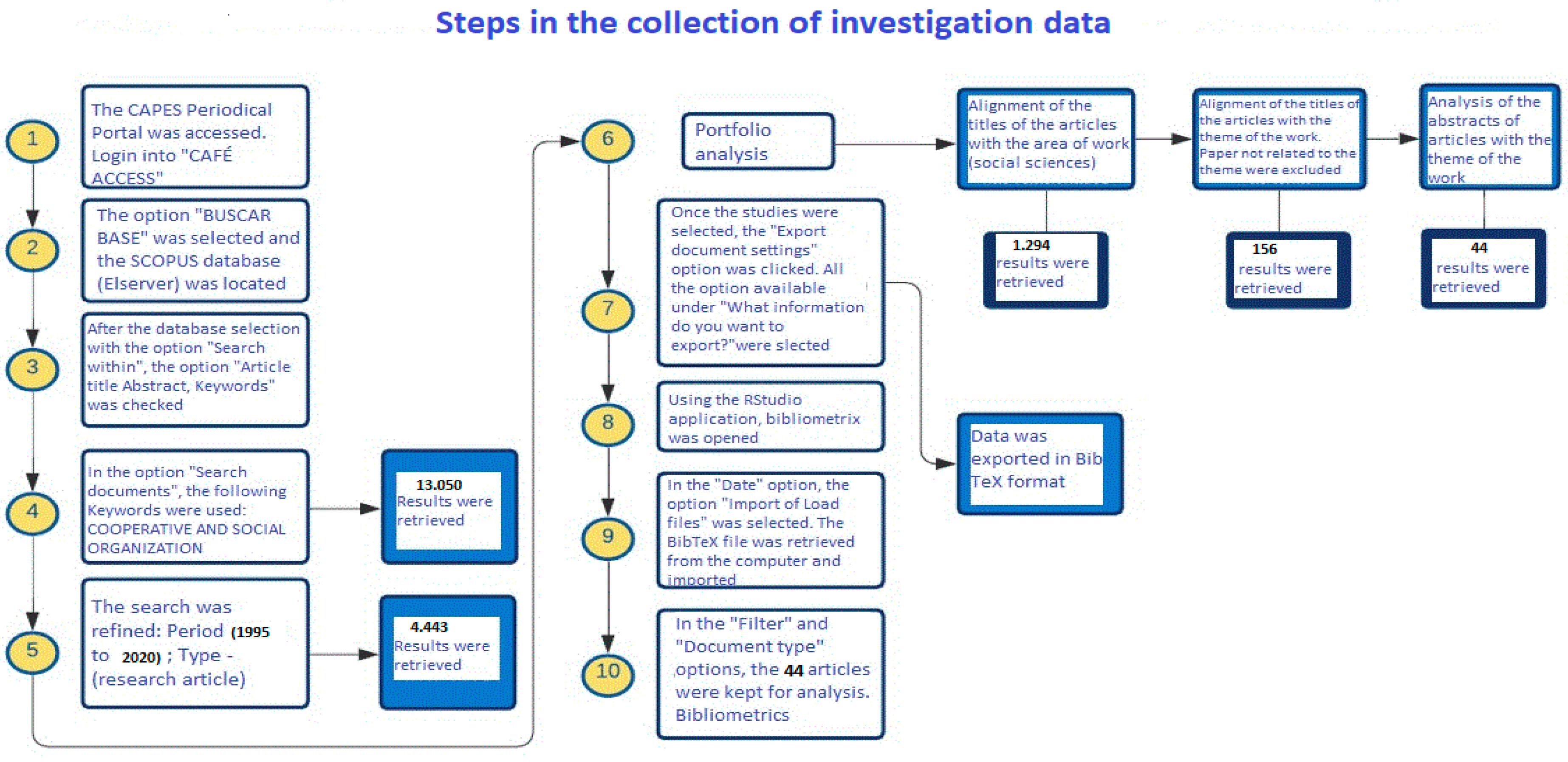

2.1. Data Survey and Portfolio Selection

2.2. Bibliometric Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antonialli, L.M.; Souk, G.G. Princípios cooperativistas e modelo de gestão: Um estudo sobre conflitos de interesses entre grupos de produtores rurais. In Congresso Brasileiro de Economia e Sociologia Rural; Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade da Universidade de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2005; Volume 43, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, E.E.D.; Lanza, F.; Santos, L.M.L.D.; Pelanda, S.S. Propriedades coletivas, cooperativismo e economia solidária no Brasil. Serviço Soc. Soc. 2011, 105, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.O. Democracia, Participação e Autonomia Cooperativa, 2nd ed.; Unisinos: São Leopoldo, Brazil, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Saucedo, D.; Nicolazzi Júnior, N.F. O trabalho na história—um longo processo de transformações. In Os Caminhos do Cooperativismo; Gedel, J.A.P., Ed.; UFPR: Curitiba, Brazil, 2001; pp. 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Simioni, F.J.; Siqueira, E.S.; Binotto, E.; Spers, E.E.; Araújo ZA, S.D. Lealdade e oportunismo nas cooperativas: Desafios e mudanças na gestão. Rev. Econ. Sociol. Rural 2009, 47, 739–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siedenberg, D.R.; Maillat, D. Dicionário do Desenvolvimento Regional; Eduniscx: Porta Alegre, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, R.S.; Capecchi, M.C.V.D.M.; Franzolin, F. O ensino de ciências por investigação nos anos iniciais: Possibilidades na implementação de atividades investigativas. Rev. Electron. Enseñanza Cienc. 2018, 17, 686–710. [Google Scholar]

- Pagani, R.N.; Kovaleski, J.L.; Resende, L.M. Methodi Ordinatio: A proposed methodology to select and rank relevant scientific papers encompassing the impact factor, number of citation, and year of publication. Scientometrics 2015, 105, 2109–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.F.T.D.; Grácio, M.C.C. Visibilidade dos pesquisadores no periódico Scientometrics a partir da perspectiva brasileira: Um estudo de cocitação. Em Questão 2013, 18, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, M. Cooperative organizations as an engine of equitable rural economic development. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2015, 3, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amonarriz, C.A.; Landart, C.I.; Cantin, L.N. Cooperatives’ proactive social responsibility in crisis time: How to behave? REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2017, 123, 7–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avsec, F.; Sÿtromajer, J. Development and socioeconomic environment of cooperatives in Slovenia. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2015, 3, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, M.; Michaud, V. Worlds, words, and spaces of resistance: Democracy and social media in consumer co-ops. Organization 2020, 27, 578–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgen, S.O. Product differentiation and cooperative governance. J. Socio-Econ. 2011, 40, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgen, S.O. Rethinking incentive problems in cooperative organizativos. J. Socio-Econ. 2004, 33, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretos, I.; Marcuello, C. Revisiting globalization challenges and opportunities in the development of cooperatives. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2017, 88, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bretos, I.; Díaz-Foncea, M.; Marcuello, C. Cooperativas e internacionalización: Un análisis de las 300 mayores cooperativas del mundo. Rev. Derechos Hum. Y Estud. Soc. 2018, 92, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, C.; Carpita, M. The impact of the economic crisis on Italian cooperatives in the industrial sector. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2014, 2, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.E.; Pacheco, G.V.; Manotas, E.N. Gestión del conocimiento y competitividad en las cooperativas con sección de ahorro y crédito. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2018, 127, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Constantinescua, L.A. Cooperative Spirit in the XXI Century European Cooperative Culture. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 27, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez, C.E.F.; Perdomo, J.F. Mejorando el bienestar de la sociedad a través del cooperativismo de plataforma. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Y Coop. 2019, 95, 161–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goel, S. Relevance and potential of co-operative values and principles for family business research and practice. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2013, 1, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S. Cooperatives and cooperative behavior in the context of family businesses. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2015, 3, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, G. Cooperative-shareholder relations in agricultural cooperatives in Turkey. J. Asian Econ. 2005, 16, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C. The co-operative model as a ‘living experiment in democracy’. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2014, 2, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Reyes, A.T.; Carmenado, I.D.L.R.; Martínez-Almela, J. Project-Based Governance Framework for an Agri-Food Cooperative. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hidalgo-Fernández, A.; Mero, N.M.; Alcivar, M.I.L.; Cruz, F.G.S. Analysis of organizational commitment in cooperatives in Ecuador. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasparian, D. Cooperativismo, políticas públicas y organizaciones sociales: Conflictividad en cooperativas promovidas por el Estado en Argentina. Psicoperspectivas 2020, 19, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.P.; Boland, M.A. One for All and All for One? A New Generation of Co-operatives Emerges. Long Range Plan. 2002, 35, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangnus, E.; Schoonhoven-Speijer, M. Navigating dynamic contexts: African cooperatives as institutional bricoleurs. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2020, 18, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pleite, F.M.C.; EID, M. El nivel de conocimiento y la reputación social de las empresas cooperativas. El caso de la Región de Murcia. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Y Coop. 2017, 91, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastronardi, L.; Romagnoli, L. Community-Based Cooperatives: A New Business Model for the Development of Italian Inner Areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazzarol, T.; Limnios, E.M.; Reboud, S. Co-operatives as a strategic network of small firms: Case studies from Australian and French co-operatives. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2013, 1, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, R.A. Cooperative games and cooperative organizations. J. Socio-Econ. 2008, 37, 2155–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narvaiza, L.; Aragon-Amonarriz, C.; Iturrioz-Landart, C.; Bayle-Cordier, J.; Stervinou, S. Cooperative Dynamics During the Financial Crisis: Evidence From Basque and Breton Case Studies. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2017, 46, 505–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J. Organisational principles for co-operative firms. Scand. J. Manag. Long Range 2001, 7, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novkovic, S. Defining the co-operative difference. J. Socio-Econ. 2008, 37, 2168–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, B.; Ozsoy, Z. Unifying nature of food: Consumer-initiated cooperatives in Istanbul. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2020, 15, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oczkowski, E.; Krivokapic-Skoko, B.; Plummer, K. The meaning, importance and practice of the co-operative principles: Qualitative evidence from the Australian co-operative sector. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2013, 1, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oorschot, K.; Hoog, J.; Van Der Steen, M.; Van Twist, M. The three pillars of the co-operative. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2013, 1, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, G.; Annosi, M.C.; Contò, F.; Fiore, M. What Are the Conflicting Tensions in an Italian Cooperative and How Do Members Manage Them? Business Goals’, Integrated Management, and Reduction of Waste within a Fruit and Vegetables Supply Chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Sanz, F.J.; Gargallo-Castel, A.F.; Esteban-Salvador, M.L. Prácticas de RSE en cooperativas. Experiencias y resultados mediante el estudio de casos. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Y Coop. 2019, 97, 137–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.B.; Vicari, S. Rural co-operative resilience: The case of Malawi. J. Coop. Manag. 2014, 2, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, F.S.D.; Calle-Collado, A.; Benito, R.M. Economía social y solidaria y agroecología en cooperativas de agricultura familiar en Brasil como forma de desarrollo de una agricultura sostenible. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Y Coop. 2020, 98, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sebhatu, K.T.; Gezahegn, T.W.; Berhanu, T.; Maertens, M.; Van Passel, S.; D’Haese, M. Conflict, fraud, and distrust in Ethioan agricutural cooperatives. J. Coop. Organ. Manag. 2020, 8, 100106. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.D.J.D.S.; Pinheiro, J.O.C.P.; Santos, E.M.D.; Costa, J.I.D.; Meneghetti, G.A. O cooperativismo como instrumento para a autonomia de comunidades rurais da Amazônia: A experiência dos agricultores extrativistas do município de Lábrea, AM. Boletín Asoc. Int. Derecho Coop. 2019, 55, 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simmons, R.; Birchal, J. The role of co-operatives in poverty reduction: Network perspectives. J. Socio-Econ. 2008, 37, 2131–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spognardi, A. Cooperatives and social capital: A theoretically-grounded approach. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Y Coop. 2019, 97, 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Széll, G. The future of cooperatives and trade unions: The relevance for the question of democratization of society. Int. Rev. Sociol. 2018, 28, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S. Towards a social theory of the firm: Worker cooperatives reconsidered. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2015, 3, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, L.V. ¿Podría estar contribuyendo el cooperativismo a fijar la población en el territorio de Andalucía? CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Y Coop. 2019, 97, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawiślak, P.A. Business Models of “New Cooperativism” Organizations as an Instrument of Sustainable Development Stimulation. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 28, 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitcer, A.; Dilworth, R. Grocery Cooperatives as Governing Institutions in Neighborhood Commercial Corridors. Urban Aff. Rev. 2017, 55, 558–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| STEPS | PROCESS |

|---|---|

| 1 | Establishment of the research intention |

| 2 | Preliminary research |

| 3 | Definition of combinations, databases, and time |

| 4 | Definitive research |

| 5 | Filtering |

| 6 | Identification of Impact Factor and citations |

| 7 | Inordinato calculation |

| 8 | Article location |

| 9 | Systematic reading and analysis |

| Authors/Publication Year | Title of the Article | Journal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [11] | Cooperative organizations as an engine of equitable rural economic Development | Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 2 | [12] | Cooperatives’ proactive social responsibility in crisis time: how to behave? | REVESCO. Revista de Estudios Cooperativos |

| 3 | [13] | Development and socioeconomic environment of cooperatives in Slovenia | Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 4 | [14] | Worlds, words, and spaces of resistance: Democracy and social media in consumer co-ops | Organization—Sage Publishing |

| 5 | [15] | Product differentiation and cooperative governance | The Journal of Socio-Economics |

| 6 | [16] | Rethinking incentive problems in cooperative organizations | The Journal of Socio-Economics |

| 7 | [17] | Revisiting globalization challenges and opportunities in the development of cooperatives | Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics |

| 8 | [18] | Cooperativas e internacionalización: Un análisis de las 300 mayores cooperativas del mundo | CIRIEC-España, revista de economía pública, social y cooperativa |

| 9 | [19] | The impact of the economic crisis on Italian cooperatives in the industrial sector | Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 10 | [20] | Gestión del conocimiento y competitividad en las cooperativas com seción de ahorro y crédito. gestión: efecto en los factores clave del éxito competitivo en el sector cooperativo | CIRIEC—España. Revista de economía pública, social y cooperativa |

| 11 | [21] | Cooperative Spirit in the XXI Century European Cooperative Culture | Procedia Economics and Finance |

| 12 | [22] | Mejorando el bienestar de la sociedad a través del cooperativismo de plataforma | Revista de estudios Cooperativos. Colombia: Dalmet |

| 13 | [23] | Relevance and potential of co-operative values and principles for family business research and practice | Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 14 | [24] | Cooperatives and cooperative behavior in the context of family businesses | Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 15 | [25] | Cooperative–shareholder relations in agricultural cooperatives in Turkey | Journal of Asian Economics. Faculty of Agriculture, Trakya University |

| 16 | [26] | The co-operative model as a ‘living experiment in democracy’ | Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 17 | [27] | Project-based governance framework for an agri-food cooperative | Sustainability |

| 18 | [28] | Analysis of organizational commitment in cooperatives in Ecuador | Journal of Management Development |

| 19 | [29] | Cooperativismo, políticas públicas y organizaciones sociales: Conflictividad en cooperativas promovidas por el Estado en Argentina | Psicoperspectivas |

| 20 | [30] | One for All and All for One? A New Generation of Co-operatives Emerges | Scandinavian Journal of Management Long Range Planning |

| 21 | [31] | Navigating dynamic contexts: African cooperatives as institutional bricoleurs | International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability |

| 22 | [32] | El nivel de conocimiento y la reputación social de las empresas cooperativas. El caso de la Región de Murcia. CIRIEC—España | Revista de economía pública, social y cooperativa |

| 23 | [33] | Community-Based Cooperatives: A New Business Model for the Development of Italian Inner Areas | Sustainability |

| 24 | [34] | Co-operatives as a strategic network of small firms: Case studies from Australian and French co-operatives | Jounal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 25 | [35] | Cooperative games and cooperative organizations | Drexel Univerasity, Philadelphia, PA, United States |

| 26 | [36] | Cooperative dynamics during the financial crisis: Evidence from Basque and Breton case studies | Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly |

| 27 | [37] | Organizational principles for co-operative firms | Scandinavian Journal of Management Long Range Planning |

| 28 | [38] | Defining the co-operative difference | The Journal of Socio-Economics Saint Mary’s University—Canada |

| 29 | [39] | Unifying nature of food: consumer-initiated cooperatives in Istanbul | Emerald Publisching Limited Society and Business Review |

| 30 | [40] | The meaning, importance and practice of the co-operative principles: Qualitative evidence from the Australian co-operative sector | Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 31 | [41] | The three pillars of the co-operative | Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 32 | [42] | What Are the Conflicting Tensions in an Italian Cooperative and How Do Members Manage Them? | Sustainability |

| 33 | [43] | Prácticas de RSE en cooperativas. Experiencias y resultados mediante el estudio de casos | CIRIEC—Espanha. Journal of Public, Social Cooperative Economics |

| 34 | [44] | Co-operative resilience: The case of Malawi | Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 35 | [45] | Economía social y solidaria y agroecología en cooperativas de agricultura familiar em Brasil como forma de desarrollo de una agricultura sostenible | CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa |

| 36 | [46] | Conflict, fraud, and distrust in Ethiopian agricultural cooperatives | Journal of Co-operative Organization and Management |

| 37 | [47] | O cooperativismo como instrumento para a autonomia de comunidades rurais da Amazônia: a experiência dos agricultores extrativistas do município de Lábrea, AM | Embrapa Amazônia Ocidental-Artigo em periódico indexado |

| 38 | [48] | The role of co-operatives in poverty reduction: Network perspectives | The Journal of Socio-Economics |

| 39 | [49] | Cooperatives and social capital: A theoretically-grounded approach | Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa |

| 40 | [50] | The future of cooperatives and trade unions: the relevance for the question of democratization of Society | International Review of Sociology |

| 41 | [51] | For a social theory of the company: the cooperatives of workers reconsidered | Journal of Organization and Cooperative Management |

| 42 | [52] | ¿ Podría estar contribuyendo el cooperativismo a fijar la población en el territorio de Andalucía? | Journal of Public, Social and Cooperative Economy |

| 43 | [53] | Business Models of “New Cooperativism” Organizations as an Instrument of Sustainable Development Stimulation | Central European Management Journal |

| 44 | [54] | Grocery cooperatives as governing institutions in neighborhood commercial corridors | Urban Affairs Review |

| Authors/Publication Year | Local/Search Region | Research Focus | Representativeness for Analysis and Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| [12] | Spain | 3 cooperatives | San Sebastian cooperatives |

| [11] | Canada | Agricultural cooperatives | Agricultural Cooperatives in Durham, Ontario, Canada |

| [13] | Slovenia | Slovenian cooperatives | Sectors in which cooperatives operate in Ljubljana |

| [14] | France | Canadian Cooperatives | Canada—organization formed by group of climbers |

| [15] | Norway | Norwegian cooperatives | Food cooperatives located in Oslo |

| [16] | Norway | Norwegian cooperatives | All cooperatives in Norway |

| [18] | Spain | 300 largest worldwide | World Cooperative Monitor- International Cooperative Alliance |

| [19] | Italy | Italian cooperatives in the industrial sector | 25,000 companies, with focus on 3000 industrial cooperatives in Trento |

| [20] | Colombia | 126 cooperatives | Trade in Barranquilla |

| [21] | Romenia | Romanian Credit Cooperatives | Credit Cooperatives operating in Romania |

| [22] | Portugal | Technology Platform Cooperativism | Universidade de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria- |

| [23] | USA | Cooperatives in Duluth (Minnesota) | Minnesota Cooperatives—Duluth |

| [24] | USA | Cooperatives in Minnesota | University of Minnesota Duluth |

| [25] | Turkey | Three types of Cooperatives focused on agriculture | Tekirdag—All agricultural credit unions, agricultural sales and agricultural development cooperatives. |

| [26] | USA | 1 Cooperative | Cooperative from Berkeley California |

| [27] | Spain | 1 Cooperative | Region of Murcia |

| [28] | Ecuador | 3 Coperatives | Ecuador’s rural sector |

| [29] | Argentina | 1 Cooperative | Cooperatives of region—Tabaja |

| [30] | USA | Cooperative Branch of USA | All cooperatives in Kansas (USA) |

| [31] | Mali and Uganda | 2 Cooperatives | A cooperative in Mali and another one in Uganda |

| [32] | Spain | Spanish Cooperatives | Region of Murcia—Southeast—interview with 321 citizens |

| [33] | Italy | 6 Cooperatives | Cooperatives from Molise region |

| [34] | Australia and France | 5 Small cooperatives | Australian Research Council (ARC) funded cooperatives |

| [35] | USA | Philadelphia Cooperatives | All cooperatives in Philadelphia |

| [36] | Spain and France | 580 Cooperatives | France: Bretagne: 2 cooperatives Spain: Basque region: 2 cooperatives |

| [37] | Sweden | Cooperatives in general | All cooperatives existing in Uppsala, Sweden |

| [39] | Turkey | 23 Cooperatives | Istanbul Cooperatives Started by Consumer embedded in alternative food systems |

| [40] | Australia | Australian Cooperative Sector | Bathurst—Australian cooperatives |

| [41] | Netherlands | 2 Cooperatives | Cooperatives in Heeze-Leende, North Brabant |

| [42] | Italy | 1 Cooperative | North of the Apulia region—one fruit and vegetable cooperative |

| [43] | Spain | 719 Cooperatives | 36 cooperatives among hose registered in the International Cooperative Alliance |

| [44] | Malawi | Rural Cooperatives of Malawi | Malawi Cooperative Unions |

| [45] | Brazil | 2 Cooperatives | 2 cooperatives in Rio Grande do Sul’s Antonio Prado and Ipê regions |

| [46] | Ethiopia | 249 Cooperatives | 4 Cooperatives of the Tigray Region |

| [47] | Brazil | 1 Cooperative | Cooperative from Lábrea (Amazonas, Brazil) |

| [48] | Scotland | Cooperatives in General | Existing cooperatives in Stirling |

| [38] | Canada | 1 Cooperative | Cooperative located in Halifax |

| [49] | Spain | 4 Cooperatives | 1 Portuguese rural village |

| [50] | Germany | 145 countries | Sapienza University of Rome |

| [51] | United Kingdom | Cooperatives in General | Cooperatives in the UK |

| [52] | Spain | All from rural areas | Andalusia—rural area |

| [53] | Poland | 40 Cooperatives | 4 cooperatives in Warsaw |

| [54] | USA | 3 Cooperatives | Carpenter—Neighborhood in West Mount Airy |

| DIFFICULTIES | STRATEGIES |

|---|---|

| Underinvestment; Risk aversion; Lack of external financing; Productive inefficiency. | Participation or workers in decision making, ownership, and profits; Cooperation with other cooperatives and organizations. |

| Small size and weak position in the markets; Slower growth than capitalist companies. | Intercooperation among cooperatives, creation of operative co-groups, cooperation with other local agents; Education for democratic values to achieve sustainability; Growth. |

| Recruiting and retaining valuable managers; Lack of manager expertise in cooperative values and culture; | Training policies and support of management; Retention by means other than monetary incentives; Education and training for managers in cooperatives; Values and culture; |

| Slowness when making important decisions; Inefficient collective decision making. | Horizontal organizational structures; Decentralization of decision-making power; Training and education in democratic decision-making. |

| NUMBER | CHARACTERISTICS |

|---|---|

| 1 | They uphold values and practices of subsidiarity and community-led development. |

| 2 | They are rooted in the surrounding communities. |

| 3 | They have clear goals for the development of the local community. |

| 4 | They respond directly to crises. |

| 5 | They present bottom-up solutions that were brought up by workers and other grassroot groups to various challenges, especially those generated by the neoliberal capitalist model, such as increased precarity and unemployment, local economic depletion, growing marginalization, and environmental degradation. |

| 6 | They provide proactive, community-led alternatives to privatization of public goods and social services. |

| 7 | They follow equitable and sustainable ethics. |

| 8 | They take on ethical-political commitments that arise not from capital structures, but from everyday experiences and needs. |

| 9 | They aim at a more equitable distribution of social wealth. |

| 10 | They are inclusive, their protagonists come from or engage with broad coalitions of community members, several stakeholders, and social justice movements. |

| 11 | They promote collective projects based on social, cultural, economic, or environmental needs. |

| 12 | They are horizontal, democratic, and co-managed. |

| 13 | They promote more horizontalized work processes, more gender-sensitive divisions of labor, more directly democratic decision-making, and shared forms of co-management. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribas, W.P.; Pedroso, B.; Vargas, L.M.; Picinin, C.T.; Freitas Júnior, M.A.d. Cooperative Organization and Its Characteristics in Economic and Social Development (1995 to 2020). Sustainability 2022, 14, 8470. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148470

Ribas WP, Pedroso B, Vargas LM, Picinin CT, Freitas Júnior MAd. Cooperative Organization and Its Characteristics in Economic and Social Development (1995 to 2020). Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8470. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148470

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibas, Walter Perpétuo, Bruno Pedroso, Leandro Martinez Vargas, Claudia Tania Picinin, and Miguel Archanjo de Freitas Júnior. 2022. "Cooperative Organization and Its Characteristics in Economic and Social Development (1995 to 2020)" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8470. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148470

APA StyleRibas, W. P., Pedroso, B., Vargas, L. M., Picinin, C. T., & Freitas Júnior, M. A. d. (2022). Cooperative Organization and Its Characteristics in Economic and Social Development (1995 to 2020). Sustainability, 14(14), 8470. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148470