Forecasting the Economic Growth Impacts of Climate Change in South Africa in the 2030 and 2050 Horizons

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Econometric Modelling

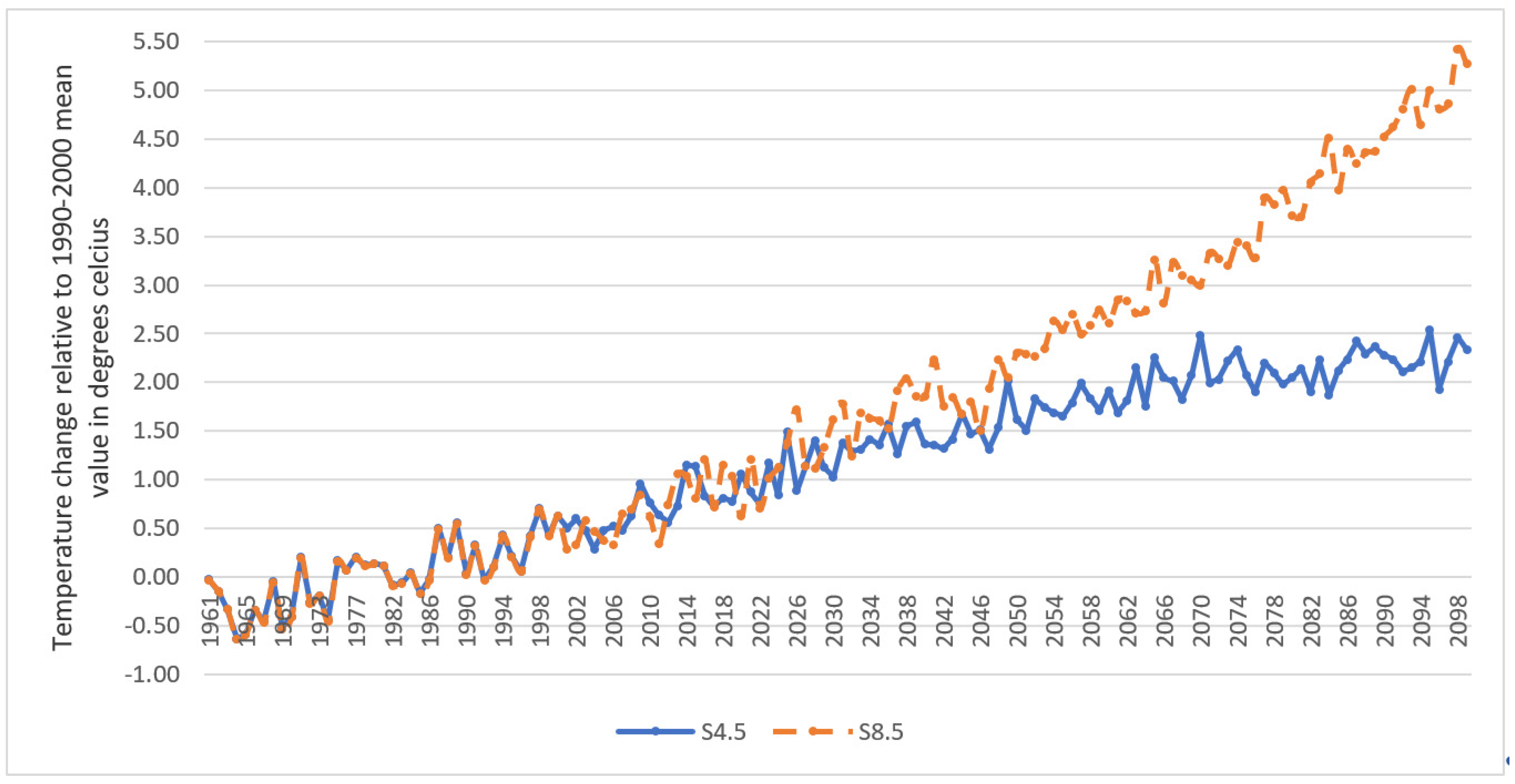

2.2. Variables and Data

2.3. Estimation Technique

3. Empirical Results and Discussion

3.1. Short-Run and Long-Run Results and the Forecasting Technique

3.2. Robustness Check

4. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Vuuren, D.P.; Edmonds, J.; Kainuma, M.; Riahi, K.; Thomson, A.; Hibbard, K.; Hurtt, G.C.; Kram, T.; Krey, V.; Lamarque, J.-F.; et al. The representative concentration pathways: An overview. Clim. Chang. 2011, 109, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiteras, R. The Impact of Climate Change on Indian Agriculture. Manuscript, Department of Economics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2009. Available online: http://econdse.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/guiteras_climate_change_indian_agriculture_sep_2009.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2019).

- IPCC Report of the 26th Session of the IPCC. Bangkok. 30 April–4 May 2007; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Deschenes, O.; Moretti, E. Extreme weather events. mortality and migration. In NBER Working Paper; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; p. 14132. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, B.; Lefgren, L.; Moretti, E. The dynamics of criminal behaviour evidence from weather shocks. J Hum. Res. 2007, 42, 489–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, E.; Satyanath, S.; Sergenti, E. Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: An Instrumental Variables Approach. J. Politi-Econ. 2004, 112, 725–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa (Stats SA). Poverty Trends in South Africa. 2017. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-06/Report-03-10-062015.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2019).

- Akram, N.; Hamid, A. Climate change: A threat to the economic growth of Pakistan. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2015, 15, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebaldi, E.; Beaudin, L. Climate change and economic growth in Brazil. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2016, 23, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; de Beurs, K.; Vrieling, A. The response of African land surface phenology to large scale climate oscillations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 2286–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abidoye, B.O.; Odusola, A.F. Climate Change and Economic Growth in Africa: An Econometric Analysis. J. Afr. Econ. 2015, 24, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adom, P.K.; Amoani, S. The role of climate adaptation readiness in economic growth and climate change relationship: An analysis of the output/income and productivity/institution channels. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fankhauser, S.; Tol, R.S. On climate change and economic growth. Resour. Energy Econ. 2005, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raddatz, C.E. The wrath of god: Macroeconomic costs of natural disasters. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1471137 (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Alagidede, P.; Adu, G.; Frimpong, P.B. The effect of climate change on economic growth: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2016, 18, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kahsay, G.A.; Hansen, L.G. The effect of climate change and adaptation policy on agricultural production in Eastern Africa. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rezai, A.; Taylor, L.; Foley, D. Economic growth, income distribution, and climate change. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.; Huang, B.; Yang, C. Assessing the coordination between economic growth and urban climate change in China from 2000 to 2015. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 732, 139283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, M.; Ahmed, M.; Naseer, M.; Slusarczyk, B.; Popp, J. The Long-Run Impacts of Temperature and Rainfall on Agricultural Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, M.; Jones, B.F.; Olken, B.A. Temperature and Income: Reconciling New Cross-Sectional and Panel Estimates. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009, 99, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burke, M.; Hsiang, S.M.; Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 2015, 527, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, M.L.; Jones, B.F.; Olken, B.A. Temperature Shocks and Economic Growth: Evidence from the Last Half Century. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2012, 4, 66–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elshennawy, A.; Robinson, S.; Willenbockel, D. Climate change and economic growth: An intertemporal general equilibrium analysis for Egypt. Econ. Model. 2016, 52, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheng, X.; Gupta, R.; Çepni, O. The effects of climate risks on economic activity in a panel of US states: The role of uncertainty. Econ. Lett. 2022, 213, 110374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, C. Extreme climate events and economic impacts in China: A CGE analysis with a new damage function in IAM. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 169, 120765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copiello, S.; Grillenzoni, C. Economic development and climate change. Which is the cause and which the effect? Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olper, A.; Maugeri, M.; Manara, V.; Raimondi, V. Weather, climate and economic outcomes: Evidence from Italy. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 189, 107156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, S.; Ouattara, B.; Strobl, E. The impact of climatic change on agricultural production: Is it different for Africa? Food Policy 2008, 33, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adom, P.K.; Djahini-Afawoubo, D.M.; Mustapha, S.A.; Fankem, S.G.; Rifkatu, N. Does FDI moderate the role of public R&D in accelerating agricultural production in Africa? Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2018, 9, 290–304. [Google Scholar]

- Adom, P.K.; Adams, S. Decomposition of technical efficiency in agricultural production in Africa into transient and persistent technical efficiency under heterogeneous technologies. World Dev. 2020, 129, 104907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiang, S.M. Temperatures and cyclones strongly associated with economic production in the Caribbean and Central America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 15367–15372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gosling, S.; Zaherpour, J.; Szewczyk, W. Assessment of Global Climate Change Impacts on Labour Productivity. 2019. Available online: https://www.gtap. agecon.purdue.edu/resources/download/9260.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Martínez-González, J.L.; Suriñach, J.; Jover, G.; Martín-Vide, J.; Barriendos-Vallvé, M.; Tello, E. Assessing climate impacts on English economic growth (1645–1740): An econometric approach. Clim. Chang. 2020, 160, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. 2021. Available online: http://www.world bank.org (accessed on 28 February 2022).

- Colacito, R.; Hoffmann, B.; Phan, T. Temperature and growth: A panel analysis of the United States (No. IDB-WP-676). In IDB Working Paper Series; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Benhin, J. Climate Change and South African Agriculture: Impacts and Adaptation Options, CEEPA Discussion Paper No. 21 Special Series on Climate Change and Agriculture in Africa; Centre for Environmental Economics and Policy in Africa, University of Pretoria: Pretoria, South Africa, 2006; ISBN1 1-920160-01-09. ISBN2 1-920160-21-3. [Google Scholar]

- South African Weather Services. Weather Forecast Data. 2013. Available online: http://www.weathersa.co.za/ (accessed on 11 December 2014).

- Department of Environmental Affairs. South Africa’s Third National Communication under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 2018. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/South%20African%20TN C%20Report%20%20to%20the%20UNFCCC_31%20Aug.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- US Library of Congress, South Africa. 2006. Available online: http://countrystudies.US/south_Africa/41.htm and http://countrystudies.us/south-africa/67.htm (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Liu, L.-C.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, L.-T.; Cao, Y.; Wang, C. Investigating the significant variation of coal consumption in China in 2002-2017. Energy 2020, 207, 118307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelevitch, R. Testing supply-side climate policies for the global steam coal market—Can they curb coal consumption? Clim. Change 2018, 150, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saba, C.S.; Ngepah, N. Convergence in renewable energy sources and the dynamics of their determinants: An insight from a club clustering algorithm. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 3483–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, C.S.; Ngepah, N. Convergence in renewable energy consumption and their influencing factors across regions: Evidence from convergence algorithm approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1993–1999 | 2004–2000 | 2005–2009 | 2010–2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 2.48% | 2.36% | 2.12% | 2.19% |

| Forestry | 0.46% | 0.44% | 0.42% | 0.43% |

| Fishery | 0.15% | 0.12% | 0.11% | 0.13% |

| Mining | 14.96% | 12.96% | 10.58% | 8.74% |

| Manufacturing | 15.90% | 16.21% | 15.88% | 15.09% |

| Electricity and gas | 2.60% | 2.41% | 2.37% | 2.08% |

| Water | 0.81% | 0.68% | 0.60% | 0.64% |

| Services | 62.65% | 64.82% | 67.91% | 70.70% |

| Total value-added (USD Billions) | 696.892 | 603.135 | 738.774 | 802.235 |

| EC | FS | GT | KZN | LIM | MP | NW | NC | WC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manu. | L-R coef | −0.021 | −0.009 | −0.004 | −0.031 | 0.006 | −0.004 | −0.004 | −0.014 | 0.009 |

| S-R coef | 0.000 | −0.019 | −0.015 | −0.011 | 0.017 | 0.015 | −0.017 | 0.000 | 0.054 | |

| Mining | L-R coef | −0.073 | −0.081 | −0.065 | −0.089 | −0.099 | −0.076 | −0.090 | −0.025 | 0.052 |

| S-R coef | −0.032 | −0.083 | −0.068 | −0.047 | −0.081 | −0.081 | −0.082 | −0.025 | 0.068 | |

| Serv. | L-R coef | −0.008 | 0.003 | −0.006 | −0.012 | −0.004 | 0.003 | 0.008 | 0.000 | −0.014 |

| S-R coef | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.008 | −0.001 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.010 | 0.019 | −0.003 | |

| Agric. | L-R coef | 0.026 | −0.007 | 0.021 | 0.055 | −0.030 | 0.094 | 0.068 | 0.046 | −0.055 |

| S-R coef | 0.013 | 0.035 | 0.070 | 0.098 | 0.080 | 0.184 | 0.101 | 0.083 | −0.069 | |

| Forest. | L-R coef | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.037 | 0.040 | 0.081 | 0.033 | 0.042 | 0.048 | −0.042 |

| S-R coef | 0.046 | 0.079 | 0.093 | 0.074 | 0.170 | 0.091 | 0.064 | 0.060 | −0.029 | |

| Fishery | L-R coef | 0.021 | 0.025 | 0.012 | 0.059 | 0.062 | 0.036 | 0.042 | 0.057 | −0.054 |

| S-R coef | 0.042 | 0.076 | 0.074 | 0.097 | 0.180 | 0.089 | 0.083 | 0.066 | −0.057 | |

| Elec. and Gas | L-R coef | −0.035 | −0.005 | 0.006 | −0.035 | 0.003 | 0.022 | −0.008 | 0.026 | −0.025 |

| S-R coef | 0.035 | 0.075 | 0.067 | 0.053 | 0.114 | 0.121 | 0.057 | 0.075 | 0.010 | |

| water | L-R coef | 0.024 | 0.021 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.045 | 0.009 | 0.039 | −0.058 | −0.076 |

| S-R coef | 0.017 | −0.003 | 0.007 | −0.027 | 0.011 | 0.006 | 0.029 | 0.069 | 0.115 |

| Mean | SE | T-Stat (p-Value) | DECISION | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Actual | 0.025 | 0.001 | 1.614 (0.107) | No statistical diff. in mean |

| Forecast | 0.024 | 0.001 | |||

| Eastern Cape | Actual | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.227 (0.821) | No statistical diff. in mean |

| Forecast | 0.021 | 0.001 | |||

| Free State | Actual | 0.033 | 0.003 | 0.801 (0.423) | No statistical diff. in mean |

| Forecast | 0.031 | 0.003 | |||

| Gauteng | Actual | 0.015 | 0.003 | −0.003 (0.998) | No statistical diff. in mean |

| Forecast | 0.015 | 0.201 | |||

| KwaZulu-Natal | Actual | 0.027 | 0.001 | 1.221 (0.223) | No statistical diff. in mean |

| Forecast | 0.025 | 0.002 | |||

| Limpopo | Actual | 0.025 | 0.002 | −0.634 (0.526) | No statistical diff. in mean |

| Forecast | 0.027 | 0.002 | |||

| Mpumalanga | Actual | 0.022 | 0.002 | 0.663 (0.507) | No statistical diff. in mean |

| Forecast | 0.021 | 0.002 | |||

| North-West | Actual | 0.023 | 0.002 * | 1.890 (0.060) | Significant mean diff. at 10% |

| Forecast | 0.018 | 0.003 | |||

| Northern Cape | Actual | 0.023 | 0.002 | 0.900 (0.369) | No statistical diff. in mean |

| Forecast | 0.021 | 0.003 | |||

| Western Cape | Actual | 0.033 | 0.002 | 1.092 (0.275) | No statistical diff. in mean |

| Forecast | 0.032 | 0.003 |

| Absolute Changes in Millions | Percentage Changes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | 2030 Horizon | 2050 Horizon | 2030 Horizon | 2050 Horizon | ||||

| RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | RCP4.5 | RCP8.5 | |

| Elec. and gas | −3408.38 | −4390.52 | −3408.38 | −4390.52 | −10.35% | −12.89% | −10.35% | −12.89% |

| Forestry | −370.53 | −449.56 | −370.53 | −449.56 | −6.79% | −8.47% | −6.79% | −8.47% |

| Agriculture | −1654.77 | −2140.36 | −1654.77 | −2140.36 | −5.70% | −7.14% | −5.70% | −7.14% |

| Fishery | −3.54 | −5.6 | −3.54 | −5.6 | −5.97% | −7.26% | −5.97% | −7.26% |

| Manufacturing | −3015.94 | −3610.42 | −3887.22 | −6032.67 | −2.25% | −2.77% | −2.89% | −4.16% |

| Mining | −84.89 | −12.2 | −84.89 | −12.2 | −1.50% | −1.94% | −1.50% | −1.94% |

| Services | −20,085.33 | −25,358.62 | −20,085.3 | −25,358.6 | −1.98% | −2.49% | −1.98% | −2.49% |

| Water | 214.14 | 281.6 | 214.14 | 281.6 | 1.78% | 2.29% | 1.78% | 2.29% |

| All | −28,409.24 | −35,685.66 | −29,280.5 | −38,107.9 | −4.10% | −5.08% | −4.11% | −5.19% |

| Province | Agri | Man | Min | Ser | For | Fis | ELG | Wat | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 4.5 | |||||||||

| Eastern Cape | 2% | −3% | −5% | −2% | −3% | −3% | −9% | 1% | −3% |

| Free State | −6% | 2% | 1% | −1% | −11% | −7% | −12% | 3% | −4% |

| Gauteng | −5% | 1% | 0% | −2% | −6% | −6% | −7% | 1% | −3% |

| KwaZulu-Natal | −5% | −3% | −4% | −2% | −4% | −5% | −11% | 5% | −3% |

| Limpopo | −22% | −2% | −4% | −3% | −22% | −26% | −18% | 5% | −11% |

| Mpumalanga | −13% | −3% | 8% | −2% | −10% | −7% | −14% | 0% | −5% |

| North West | −4% | 2% | −1% | 0% | −4% | −5% | −8% | 1% | −2% |

| Northern Cape | −6% | −2% | 0% | −3% | −2% | −1% | −6% | −1% | −3% |

| Western Cape | 2% | −8% | −2% | −2% | −2% | 1% | −6% | −6% | −3% |

| National | −5.70% | −2.25% | −1.50% | −1.98% | −6.79% | −5.97% | −10.35% | 1.78% | −4.10% |

| Scenario 4.5 | |||||||||

| Eastern Cape | 2% | −4% | −6% | −3% | −4% | −4% | −11% | 1% | −4% |

| Free State | −7% | 2% | 1% | −2% | −13% | −8% | −15% | 4% | −4% |

| Gauteng | −7% | 2% | 1% | −3% | −8% | −9% | −9% | 1% | −4% |

| KwaZulu-Natal | −7% | −3% | −5% | −2% | −6% | −6% | −14% | 7% | −4% |

| Limpopo | −27% | −2% | −5% | −4% | −28% | −32% | −23% | 6% | −13% |

| Mpumalanga | −15% | −4% | 10% | −3% | −12% | −8% | −17% | 1% | −6% |

| North West | −5% | 2% | −2% | 0% | −5% | −6% | −9% | 1% | −3% |

| Northern Cape | −7% | −3% | 0% | −4% | −3% | −2% | −8% | −2% | −4% |

| Western Cape | 3% | −9% | −2% | −3% | −3% | 1% | −7% | −7% | −3% |

| National | −7.14% | −2.77% | −1.94% | −2.49% | −8.47% | −7.26% | −12.89% | 2.29% | −5.08% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ngepah, N.; Tchuinkam Djemo, C.R.; Saba, C.S. Forecasting the Economic Growth Impacts of Climate Change in South Africa in the 2030 and 2050 Horizons. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148299

Ngepah N, Tchuinkam Djemo CR, Saba CS. Forecasting the Economic Growth Impacts of Climate Change in South Africa in the 2030 and 2050 Horizons. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148299

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgepah, Nicholas, Charles Raoul Tchuinkam Djemo, and Charles Shaaba Saba. 2022. "Forecasting the Economic Growth Impacts of Climate Change in South Africa in the 2030 and 2050 Horizons" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148299

APA StyleNgepah, N., Tchuinkam Djemo, C. R., & Saba, C. S. (2022). Forecasting the Economic Growth Impacts of Climate Change in South Africa in the 2030 and 2050 Horizons. Sustainability, 14(14), 8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148299