2. Literature Review on CSR Drivers and Barriers

In order to select the specific CSR drivers and barriers to be analyzed in an industrial sector (considering both emerging and developed markets) we reviewed the related literature. Drivers and barriers have been classified in many different ways, depending on the study approach and characteristics [

12].

Analogously to the abovementioned two major CSR perspectives described by [

2], “instrumental/economic” vs. “injunctive/social”, currently there are two main lines of thought debating the nature of CSR factors [

3,

13]. One is the instrumental use of CSR, whereby CSR is considered as a means to increase the company’s financial results and market value: profit driven, also referred to as strategic driven, based on the assumption that a higher corporate social performance (CSP) leads to a correspondingly higher corporate financial performance (CFP) [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

The other mainstream line of thought regarding the most influential CSR factors is focused on moral values (holistic interpretation) [

12,

20,

21]. The personal core values of the organization’s top managers and founders have been established as a key CSR driver [

22,

23,

24], since they can play a significant role in the contents and key aspects of CSR practices and implementation. For instance, a study encompassing 100 reputable Spanish firms found that socially responsible firms are comparatively more inclined to foster long-term relationships with stakeholders, rather than maximizing their short-term profit [

25].

Regarding other previous studies on multinational corporations’ (MNCs’) CSR drivers, it has been reported that when MNCs have pursued a predominantly reactive CSR strategy, they are mainly influenced by external drivers (

external meaning stemming from the environment outside the firm, such as legal regulations), while as when MNCs have followed a proactive CSR strategy, they have generally been influenced by internal drivers (

internal meaning concerning specific firm characteristics, such as company values and objectives, top management’s values, commitment and personal features) [

26].

An empirical study encompassing 416 Spanish firms [

3] analyzed both subjective (conditioned by morals) and objective (not conditioned by morals) CSR drivers, concluding that both act as mediators of the CSR approach adopted by the companies. In their research, the most relevant subjective CSR driver was the integration of ethics and sustainable development principles, and the most relevant objective CSR driver was stakeholder pressure.

A literature survey of CSR determinants in developing economies revealed that both internal and external factors influenced the disclosure of CSR information [

27]. These authors pointed out that the analysis of differences in determinants and motivators by region has been neglected, thus reinforcing the abovementioned relevance of comparing developing and developed markets.

2.1. Selected CSR Drivers, Analysis/Representation Approach

On the basis of this literature review, we have selected as the starting base list of CSR drivers, the 20 CSR determinants of internal and external motivations for companies to engage in CSR proposed by [

26]. In their study, they analyze “how” and “why” a large European company engages in CSR and sustainability.

We also draw upon the article “

What Motivates Managers to Pursue Corporate Responsibility? A Survey among Key Stakeholders” [

28], in order to refine this starting base list (as described below) and to establish the analysis approach and the graphical representation of results.

These authors asked their panels to evaluate the relevance of their selected list of CSR drivers from two perspectives: the current, perceived or “as-is” situation, and the desirable, “should-be” viewpoint. In this paper, we apply their method to ask which currently are and also which should be the most influential CSR drivers. We also follow their advice to engage in ethical reflection, as well as on the use of surveys for complementary empirical analysis of the eventual discrepancies found between current practices (as-is situation) and the future, desirable (should-be) situation. In their research, they found that, while the drivers currently considered by their panel as being most influential (as-is) were mainly instrumental, e.g., seeking branding and reputation-building, their panel reported a clear willingness for sustainability and ethics to take a much more important role. Thus, ethics-based drivers were deemed more relevant in the desirable (should-be) situation, without discarding the instrumental drivers such as those mentioned.

Regarding graphical representation of results, the results they obtained were depicted through radar graphs. We decided to use the same radar graphical representation to describe and compare the current and desirable scores for each factor.

This starting base list of CSR drivers based on the determinants proposed by [

26] was then slightly modified as follows. Legislative recommendations were merged with the legal and regulatory framework of the country, resulting in a driver defined as

legal and regulatory framework (legislative compliance obligations and recommendations); and pressure from financial markets and pressure from socially responsible investors were merged into

pressure from ethical financial markets and socially responsible investors (SRIs), since CSR integrates transparency and affects investor confidence.

We then further refined the resulting 18-item list with two additional drivers [

28]. One derived from the sustainable development approach to CSR, defined in our list as

sustainability, i.e., the commitment to sustainable development and transformation of industrial focus from a purely financial emphasis to a broader environmental and social orientation [

29]. Another driver came from the institutional isomorphism approach, to identify the normative diffusion of CSR through advisory and consultancy services [

30].

Since we had identified the analysis of specific industrial sectors as a centerpiece for our research, we also drew upon an industrial sector research by [

31], which studied the drivers, motivations and barriers to the implementation of CSR practices by construction companies. In their literature review they identified 13 drivers (3 drivers and 10 motivations). Regarding drivers, they identified policy pressure (PP); market pressure (MP) and innovation and technology development (IT); as for motivational drivers: financial benefits (F); branding, reputation, and image (BR); human resource benefits (HR); supplier-induced benefits (SI); persuasion and inspiration (PI); relationship building (RB); policy benefits (PB); organizational culture and awareness (OC); strategic business direction (SD); and resource and capability availability (RC). These drivers have been cross-checked within the list and assigned to the different categories in

Table 1 below.

The resulting 20 CSR drivers are briefly described below. They are divided into 10 internal and 10 external drivers. Some drivers are further described to understand some relevant variants as per the different related research work reviewed.

2.2. Selected CSR Barriers

Research carried out by [

10] focused on the promotion of sustainability through CSR implementation in the manufacturing sector. In their literature review, however, they identified various CSR barriers in several industrial sectors.

They suggest, as a line of research, exploring CSR drivers and barriers by industrial sector, thus reinforcing the abovementioned relevance or following a sector-oriented research approach.

A study on CSR drivers and barriers in Spain was performed by [

3], including a selection of the most influential factors for analysis and the description of the different drivers and barriers that affect CSR in Spanish firms. We drew upon this work by using their proposed list of ten CSR barriers, as shown in

Table 2. In order to enrich the list of barriers and relate it to the research contributions of other authors, we cross-checked and mapped the CSR barriers used in two other relevant articles against this list, as discussed below.

In the study published by [

31], by identifying the drivers, motivations and barriers to the implementation of CSR practices by construction companies, they identified five barriers: government policy (GP); construction enterprises—resources, capabilities and training constraints—(CE); attributes of CSR—resource consumption at early stage—(A); stakeholder perspective—lack of communication, coordination and cooperation—(SP); and construction industry—lack of CSR knowledge and framework among customers and stakeholders—(CI). These barriers have been cross-checked against the list proposed by [

3] and mapped to the corresponding barriers in

Table 2 to facilitate cross-referencing and comparison.

We also considered the identification made in an Indian textile company case study [

32], where twelve common barriers for CSR implementation were identified: lack of stakeholder awareness (B1), lack of training (B2), lack of information (B3), financial constraints (B4), lack of customer awareness (B5), lack of concern for reputation (B6), lack of knowledge (B7), lack of regulations and standards (B8), diversity (B9), company culture (B10), lack of social audit (B11) and lack of top management commitment (B12). These barriers have also been mapped to the most closely related barriers in

Table 2 below.

Thus, as a starting point for our study, we used the resulting list of ten barriers shown and briefly described in

Table 2. They are divided into five barriers associated with the managers’ moral values and five associated with the managers’ perception of the CSR business case (managers’ cost-benefit analysis of CSR).

3. Materials and Methods

As discussed in the previous sections, in this paper we attempt to bridge the identified research gap by exploring CSR drivers and barriers in the context of a specific industrial sector, while shedding some light on the particularities of emerging markets. Furthermore, both the current (“as-is”) and the desired (“should-be”) states will be analyzed and compared.

Thus, the general objectives for this paper, within which more specific hypotheses will be framed, can be summarized as:

To bridge the identified research gap by exploring CSR drivers and barriers in the context of a specific industrial sector, and supporting a structured comparison of the results found along the various study dimensions (e.g., current vs. desired states or developed vs. developing markets). This should contribute to a better understanding of the particularities of these dimensions and of facets such as the company’s and the environment’s culture.

To this end, the lists of 20 CSR drivers (classified into internal vs. external) and 10 CSR barriers (classified into moral values vs. business case) that will be used in the analysis have been compiled and justified (

Table 1 and

Table 2).

In order to achieve this, and in line with the approach followed in similar research CSR projects by other authors [

6,

33,

34,

35] the basic methodology chosen for this empirical study was the qualitative research, based on in-depth case studies.

This qualitative research was complemented with a quantitative approach aimed at better summarizing the findings and at supporting a structured comparison of the results found along the various study dimensions (e.g., current vs. desired states or developed vs. developing markets).

In order to carry out the in-depth case studies, two major corporations from the same sector (aerospace and defense) were selected: Airbus and Tata Advanced Systems Limited (TASL).

Aerospace and defence is a highly relevant global economic sector that, in spite of some specific studies [

6], remains largely understudied. It encompasses major companies (as well as smaller ones) in both developed and developing markets.

Within that sector, two major companies, leaders in their respective markets, were selected, one from a developed market (Europe), another from a developing market (India). Airbus is the leading European company in this sector, and a member of the global duopoly (the other being the U.S. based Boeing). It is an international corporation operating in over 180 sites, with 12,000 global vendors. It comprises three divisions that share the same “Airbus” brand: commercial aircraft, helicopters and defense and space. As per the 2021 Airbus Annual Report, the company had 126,495 employees from over 100 nationalities and had revenues exceeding 52 billion Euros [

36]. Tata Advanced Systems Limited (TASL), a private industry belonging to Tata Group Multinational, is the leading aerospace and defense company in India. It belongs to the Tata Group, the largest industrial multinational in South-East Asia, encompassing 30 companies and over 800 thousand employees; the TASL group has over 5000 employees [

37]. It is worth mentioning that India was the first country in the world to make CSR compulsory for companies, as per the 2013 law of companies, amended in April 2014. Recent research suggests that investing in Indian domestic CSR improves the scope of internationalization for emerging-market multinational enterprises [

38].

Furthermore, the employment relationship with Airbus and intense business relationship with TASL of one of the authors allowed for a much deeper understanding of the environment and better access to both companies’ management on such a sensitive topic as CSR that would not have been feasible otherwise.

Within the framework of the general objectives for this paper stated above, and once the specific case studies were selected, two more specific hypotheses to be tested could now also be specified:

H1. The main type of CSR drivers at Airbus and TASL are internal, not external.

H2. The main CSR driver at Airbus and TASL is the personal moral values of the top management.

The process to outline these hypotheses is based on the literature review carried out, which suggests the two major controversies currently being debated among CSR scholars: the relative weight of internal vs. external determinants and the profit vs. moral driven orientation.

Figure 1 depicts a process flow to define the hypotheses. The choice of H1 is based on published research that suggests that the internal drivers and values of individual companies may lead to a higher level of CSR awareness, implementation and proactiveness, as compared with the effect of external pressure and drivers on CSR practices [

26,

39]. H2 is framed considering studies which report that personal core values of top management and founding entrepreneurs can play a significant role in the contents and key aspects of CSR practices [

22,

23,

24].

The research field work aimed at both achieving these general objectives and testing these specific hypotheses was structured as a two-step process, firstly carrying out a structured interview and then completing a related survey with Airbus and TASL managers. The same methodology was applied in both firms.

We selected Airbus and TASL CSR-related managers from all divisions of Airbus and different areas in TASL to obtain a comprehensive scope of the data. Participants’ demographic data are included in

Appendix A. In total, 35 top managers from both firms participated in this research and were interviewed.

Regarding the areas from which the participants were drawn, in the case of Airbus, eleven (11) came from the CSR and sustainability area, four (4) from procurement and supply chain, three (3) from communication and one (1) from general management. In the case of TASL, four (4) were from human resources and corporate social responsibility, four (4) from general management, three (3) from manufacturing, two (2) from procurement and supply chain, two (2) from project management and one (1) from engineering.

After each structured interview, recorded testimonies were transcribed into a written document for analysis.

The same survey was used in both firms, after the interviews, to gather quantitative data about the same questions that had been discussed in depth during the structured interview. It covered the 20 CSR drivers and the 10 CSR barriers. The survey was delivered to all the interviewees. After a careful screening, 28 completed surveys (out of the 35 interviewed participants) were deemed sufficiently complete to be included in the analysis.

Participants were asked to assign a score ranging from 0 (no influence) to 10 (maximum influence) to quantify the leverage of the 30 variables on CSR. The relevance of the 20 drivers was assessed both for the current state (as-is) and for the desirable state (should-be).

Testimonies of the interviewees and survey results constituted the primary data used in the study. To complement the analysis, the companies’ public reports and documents from the Airbus and TASL websites were used as secondary data.

As the first step to carrying out the quantitative analysis, to support and complement the qualitative analysis, descriptive non-parametric statistics were applied to the survey results; the results were presented in tabular and graphical formats.

In order to achieve the stated objective of supporting a structured comparison of the results found along the various study dimensions (e.g., current vs. desired states or developed vs. developing markets), non-parametric paired Wilcoxon tests were then applied to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences observed between the current and the desired states, both for Airbus and for TASL. Radar graphs were used to illustrate the differences in results between Airbus (developed market) and TASL (developing market); the statistical significance of these differences was then assessed through non-parametric, non-paired Wilcoxon tests (since the two respondents’ populations were different, paired tests could not be used).

The interpretation of these results and the drawing of conclusions was based on the insights provided by the testimonies provided during the structured interviews.

4. Results

As stated in the methodology, this section presents survey results, complemented by the testimonies from the structured but open-ended interviews, for each company, for both as-is and should-be CSR drivers and for the key barriers. The statistical significance of the differences found between the as-is and the should-be states is also assessed.

4.1. Airbus Results

Non-parametric medians were used to represent the survey results in the following three tables,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5. Means were used as tie-breakers for the ranking. To facilitate cross-reference, the driver columns in these tables contain, in addition to the driver’s short-name, the original coding (internal 1–10, external 1–10) assigned in

Table 1. This short code (INT-1, INT-2…) is also used in the summarized graphs and tables below, e.g., in

Table 6. Analogously, barrier tables include the original coding (moral values 1–5, business case 1–5) assigned in

Table 2.

Survey results for Airbus show that, in the current state (as-is), the CSR drivers reported by the participants as being most influential are predominantly external. The external drivers “legal and regulatory compliance framework” and “sector codes of conduct shaping industry behavior” hold the top two positions. They are, however, followed by two internal drivers: the “geographic MNC span of activities”, which includes aspects such as the corporations’ visibility, foreign partners and international diversification; and the “Firm size”. The remaining spot among the top-5 drivers is held by another external driver, the national business systems across Airbus operating countries. Copying and imitating sectorial trends also exerts a positive influence in CSR, consistent with the notion that the spillover effect of the adoption of CSR is a strategic response to competitive threats [

40]. Nevertheless, rather than merely copying/imitating, unique CSR strategies could more effectively promote stakeholder engagement by helping firms develop differentiated and unrivalled positions with key stakeholders, as suggested by the positive association between CSR uniqueness and market value reported by [

41].

Among the top 10, the following five positions are preponderantly occupied by internal drivers: past financials, which condition the funds available for investments, e.g., in CSR and sustainability projects (internal); the company governance system, encompassing such elements as guidelines, policies, procedures and standards (internal); the values of the top management (internal); the pressure from ethical markets (external); the characteristics of the industry sector (internal); and, with a tied median value of 6, the pressure from the media (external).

These survey results are supported and complemented by the participants’ structured but open-ended testimonies during the interviews. They highlight the significance in Airbus, as a CSR driver, of the influence of the employees at all levels. Interviewees emphasize the relationship and inter-dependence between top management leadership and a set of company values based on the vision that business integrity promotes the evolution towards a CSR driven by the United Nations sustainable development goals (SDG). They also stress the relevance of environmental, social and governance (ESG) ratings, socially responsible investors (SRI), the legal framework and the role played by non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

When interviewees are asked in the survey about the desired, should-be state, 7 out of the top 10 as-is CSR drivers also make it to the top 10. There are relevant differences, however, in their relative position. The internal driver “top management values” becomes the top should-be CSR driver. The sustainability factor undergoes a most remarkable reshuffle, jumping from the 19th all the way to the 2nd position. It thus becomes the driver whose priority/relevance, according to these experts, should change the most. Along similar lines, stakeholdership climbs 13 positions (18th to 5th) and firm objectives moves up to the third position. As per the interviewee’s testimonies, this is aligned with the definition of a new company purpose at Airbus and the adoption of modern strategies, which emphasize dialogue with stakeholders in order to be able to maximize the positive impact of corporations.

Complementary testimonies stemming from the interviews, regarding the should-be drivers, reinforce and further clarify these survey results. Participants argue that a major CSR driving force should be a genuine purpose, aimed at a positive impact on society and environment, considering not only the direct stakeholders but also the population at large. Particular focus is placed on a specific stakeholder, the customers, due to the importance of eco-design and lifecycle assessment requirements. The various CSR drivers are perceived as interconnected pillars; thus, their combined impact cannot be understood in isolation. Partnerships also play a key role, particularly in the development of technologies that can contribute to the vision and mission of pioneering a sustainable aerospace industry.

As for the top 5 CSR barriers, according to the survey results they are mainly related to the business case analysis of CSR (see

Table 2), and, more specifically, to a shortage of CSR and sustainability knowledge, time scarcity, lack of economic resources/monetization and structure/staff; as well as to CSR focusing on image and reputation rather than reflecting a true strategic conviction. Along the same lines, testimonies from the interviews pointed out, as CSR barriers, to management focused solely on profit and to the overlooking of holistic sustainability benefits. Regarding the low institutional interest, interviewees suggested that governments should strive to promote and facilitate the path towards CSR development in the aerospace and defense industry. This suggestion would be supported by research reports linking countries with higher corporate social responsibility penetration, such as India, with higher income growth rates [

42]. Median scores of relevance are generally higher in business-case-related barriers, with a median of medians of 4, as compared to 3 for the moral-values-related barriers.

As previously discussed, in order to achieve the stated objective of supporting a structured comparison of the results found along the various study dimensions (e.g., current vs. desired states), non-parametric matched-pairs Wilcoxon tests were then applied to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences observed between the as-is and the should-be states. The resulting

p value significance levels for Airbus are shown in

Table 6.

The matched-pairs Wilcoxon test indicates that statistically significant differences are detected for 50% of the drivers. Since the median of the differences is different from zero with p values significant at the 0.05 level, we find that there is a statistically significant difference between the as-is and the should-be pairs of data (the scores assigned by the same respondent to the same driver, for the as-is and the should-be states). These significant differences occur more among the internal drivers (in 6 internal and 4 external drivers), thus reflecting that in the opinion of Airbus CSR top leaders there is still more work to do in the internal drivers than with regard to external factors.

4.2. TASL Results

Concerning

Table 7, the as-is situation, the most important drivers were the top management values followed by the relation with stakeholders, firm objectives, top management features and the company governance system, all of which were internal. Firm ownership, the sustainability challenges and the legal requirements also play an important role influencing CSR, according to the respondents. There are also other factors with substantial influence, such as the requirements of ethical markets, the national system, the money available for CSR as per the past financials results and the sector codes of conduct. The contributions from the interviews provided complementary, aligned insights. TASL participants highlighted that the most influential driver is the Tata Group value system, the aspiration to serve the communities and the culture of commitment to serve people and the environment, in line with the company purpose. Legal requirements are also considered relevant, but at a second tier.

Survey results show that both in the as-is (

Table 7) and should-be states (

Table 8), the CSR drivers deemed as most influential are internal to the company.

Regarding

Table 8, the should-be state, the top 5 most important drivers are the top management values followed by the relation with stakeholders, the firm objectives, top management features and the company governance system. Firm ownership, sustainability and legal framework also play an important role influencing CSR. There are other external factors with high influence, such as the Indian national system, which is considered to be influential in the desired, future-state state. Regarding the importance assigned to the relation with the stakeholders, in terms of aeronautical customers, some authors have reported that an airliner’s participation in social and environmental activities is positively and significantly correlated with a higher level of financial efficiency [

43]. In order to avoid environmental degradation, stakeholders increasingly require green-friendly practices and disclosure [

44].

The results of the interviews emphasize the importance of the value system and participation by all the employees. Interviewees consider that a focus on servicing the society as a whole should permeate the company’s culture and be driven, with top-down support, to inform specific actions.

Table 9 shows that the main TASL CSR barriers are the limitative assumption that CSR is especially applicable in large corporations (which is a moral-values-related barrier, MV), followed by a set of mainly business-case-related barriers (BC): issues of time scarcity (BC), low institutional interest (lack of governmental willingness and official grants) (BC), availability of economic resources/monetization (BC), focusing only on solidarity (MV), low CSR knowledge (BC) and lack of CSR structure and staff (BC).

During the interviews, the participants focused on the resources and CSR knowledge availability constraints, as well as on the difficulties involved in appropriately selecting and planning the projects to which the limited funds would be assigned.

As in the Airbus case, non-parametric matched-pairs Wilcoxon tests were then applied to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences observed between the as-is and the should-be states. The resulting

p value significance levels for TASL are shown in

Table 10.

As shown in

Table 10, 40% of the drivers are marked with an asterisk, thus signaling resulting

p values of less than 0.05. Thus, there is enough statistical evidence to reject the null hypothesis, thus the median of the score differences between the as-is and should-be pairs is not zero. This indicates that there are also significant statistical differences between the as-is and the should-be answers for TASL. These results occur more on the internal drivers, in 6 internal vs. 2 external drivers. The fact that more significant differences are found in the internal drivers, suggests that TASL managers consider that there is more work to do at internal level than at external level to improve the implementation of CSR in TASL.

5. Discussion

In the previous section, survey results and interview testimonies have been presented, separately for Airbus and TASL, for both as-is and should-be CSR drivers (along with the statistical significance of the as-is vs. should-be differences) and for the key barriers.

These results constitute a first step towards testing hypotheses H1 and H2 and provide the basis for achieving the more general stated objective of supporting a structured comparison of the results found along the various study dimensions (e.g., current vs. desired states or developed vs. developing markets).

This section will further analyze and discuss these results, in order to attain the stated objectives. Radar graphs will be used for data visualization and comparison, to illustrate the differences in results between Airbus (developed market) and TASL (developing market); the statistical significance of these differences will be assessed through non-parametric, non-paired Wilcoxon tests. Detailed inputs from the interviews will allow an insightful interpretation of these observations.

5.1. Statistical Significance of the Survey Differences Observed between Airbus and TASL

In the quest to support a structured comparison along the various study dimensions (e.g., current vs. desired states or developed vs. developing markets), the existence of a statistically significant difference between current and desired state results has been established (both in Airbus and in TASL) in the previous sections.

In this discussion chapter, differences and similarities observed between Airbus and TASL responses will be analyzed and discussed, drawing on the interview testimonies, looking for contributions that help to understand the role played by different cultures and market/external environment situations. Thus, the first question to be answered, prior to the discussion of specific differences, is whether the differences found in the survey results for Airbus and TASL are statistically significant.

As justified in the Materials and Methods section, this significance will be assessed through non-parametric, non-paired Wilcoxon tests (since the two respondents’ populations are different, paired tests cannot be used). Thus, in each of the subsequent sections, the radar graph depicting and comparing median results for Airbus and TASL will be followed by a table reflecting the statistical significance of the observed differences, for each factor.

5.2. Discussion of the Current (as-Is) State for CSR Drivers

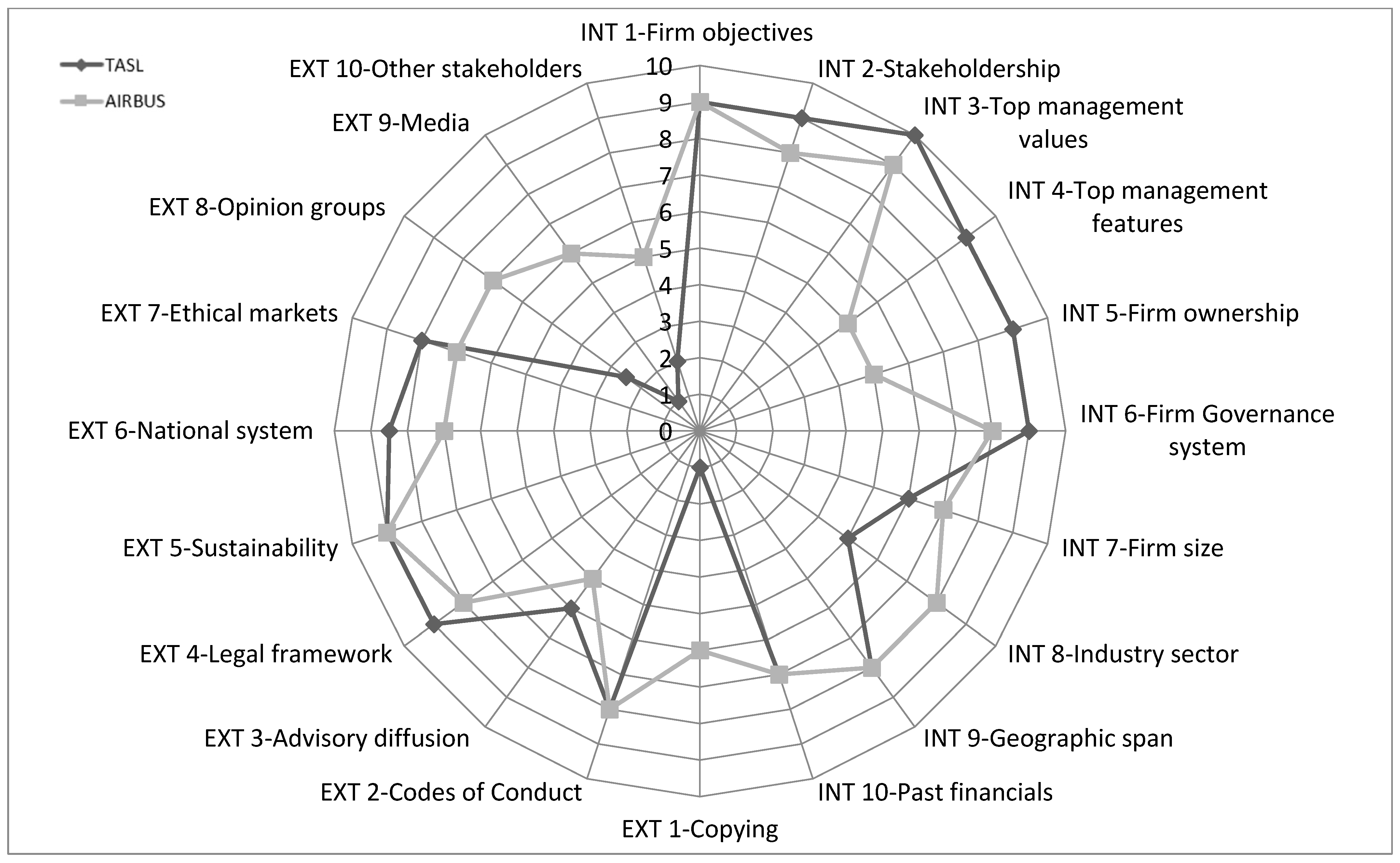

The radar graphic in

Figure 2 depicts the (non-parametric) median survey scores, in the current, as-is situation, for the various CSR drivers in Airbus and TASL, drawing data from

Table 3 and

Table 7.

The

p value significance levels for the differences between Airbus and TASL results, for these as-is CSR drivers, assessed through non-paired Wilcoxon tests, are shown in

Table 11.

Both the marked contrast in the shape of the corresponding radar graphs and the fact that almost 50% of the drivers present statistically significant disparities (mainly the internal ones), suggest the existence of underlying, structural differences between the current situation in Airbus and TASL, which might potentially be attributable to their different geographic areas, market development states and cultures.

Regarding the different cultures of the two companies, several drivers that have been linked to organizational culture and awareness, such as top management values, stakeholdership, firm objectives and firm governance system [

31], are among those exhibiting statistically significant (

Table 11) and marked (

Figure 2) differences between the two companies.

These culture-related divergences may be attributed to India’s cultural heritage, which is a key determinant of its CSR environment. It can be traced back to the pre-industrialized periods, in which religion, philanthropy and charity combined to shape CSR in India towards inclusive social development [

45]. This environment can foster ethically focused or humanitarian visions (including those of Tata’s founder, Jamsetji Tata) that are extensively applied in TASL. They help to explain widespread CSR practices such as participating in charity activities, providing care and support for disadvantaged groups and assisting in public health and disaster prevention activities [

24]. These activities, reported on the TASL website, are also highly influenced by the legal framework built around Section 135 of India’s 2014 Companies Act, which mandates organizations to spend a minimum of 2% of the profits on CSR activities.

In stark contrast with TASL’s predominantly culture-driven CSR approach, the main current drivers in Airbus, as a European firm framed in a developed economic zone subject to intense competition, are resource-related. Airbus is a much larger multinational. Thus, according to the respondents, its sheer size, global reach and industrial sector leadership allow it to leverage the resources required for both internal projects (aimed at increasing the sustainability of its products, services and its overall supply chain) and major external projects to support communities as a global citizen. TASL is more prone to implementing projects related to the local communities.

Testimonies from the interviews confirm this difference in focus, whereby the most important driver in Airbus is external (legal and compliance regulation), while as in TASL it is internal, the top management values, consistently attributed by the interviewees to the influence of the foundational Tata Group value system. On the other hand, legal and compliance regulation is perceived as a major factor in TASL, by determining budgets and conditioning the specific CSR organization.

Contrasting positions arise among interviewees while assessing the influence of external stakeholders’ expectations as CSR drivers. For Airbus they are a key CSR driver, contributing to the necessary company alignment. The main framework within which to manage the relationship with the stakeholders is the Airbus contribution to the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and the publication on its website of the materiality matrix reflecting the communication activity with stakeholders. On the other hand, such practices are not found on the TASL public website, which does not contain a materiality matrix or sustainability report about their stakeholder management activity, except for the reference to the social support projects within local communities that have been undertaken, and the diversity and inclusion policy. This might represent an opportunity, since CSR investments in the community have been characterized as being positively related to financial performance in resource-intensive industries [

46].

5.3. Discussion of the Desired (Should-Be) State for CSR Drivers

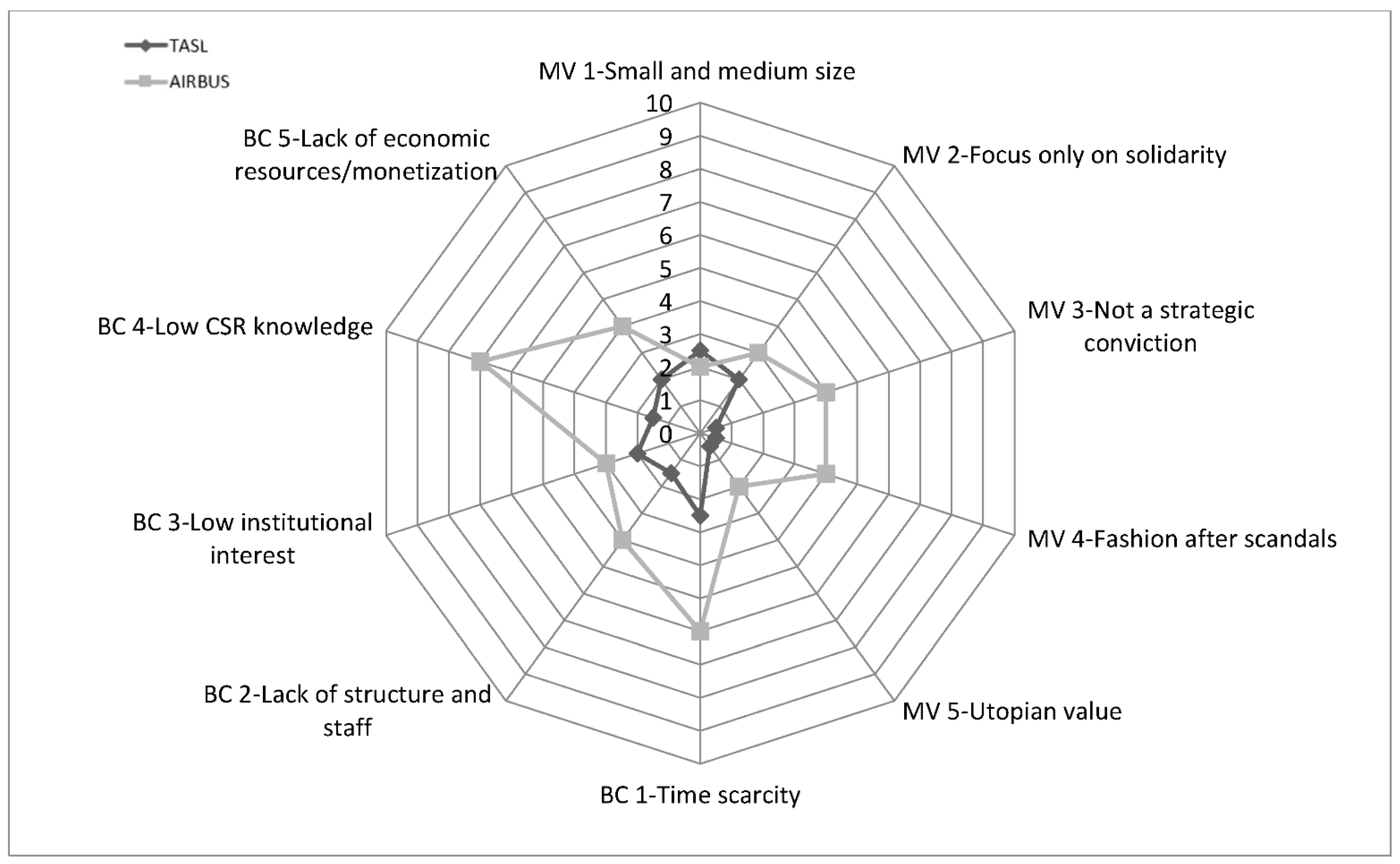

The radar graphic in

Figure 3 depicts the median survey scores, in the desired should-be situation, for the various CSR drivers in Airbus and TASL, drawing data from

Table 4 and

Table 8.

The

p value significance levels for the differences between Airbus and TASL results, for these should-be CSR drivers, assessed through non-paired Wilcoxon tests, are shown in

Table 12.

As compared with the current, as-is situation, the less pronounced differences in the shape of the corresponding radar graphs and the fact that fewer drivers present statistically significant disparities (in this case, predominantly the external ones, rather than the internal drivers as in the as-is situation), suggest a certain convergence in the way to look at the desirable future in the aerospace and defense industry, even by firms that come from different geographic areas, market development states, cultures and starting situations.

Thus, top management values and firm objectives also rise to prominence in Airbus for the should-be state. The testimonies from the interviews reveal that, when looking at the desired future, both companies are aligned in putting values first; the influence of all the employees, particularly the leaders, is deemed essential to enable CSR to grow from the deep core of the organization.

In the TASL case, nearly all the participants agree on continuing with the same value-driven culture that has brought fast-growing success. Nevertheless, they emphatically advocated a shift from excessive reliance on the top management to an approach that fosters an active involvement by all employees. This could also result in a positive retention effect associated with employee participation in corporate initiatives with explicit social impact goals [

47].

In Airbus, shareholders, CEO and top management are considered key as they have the power to promote CSR and push it forward. Employees are also considered as the actual CSR engines, since they enable CSR to “actually happen”, by implementing evolutionary programs fostering a sustainable aerospace and by executing projects within the Airbus Foundation. This evolutionary path provides a benchmark for younger companies, such as TASL, that are eager and, in a position, to take the opportunity to embark on the sustainable aerospace ambition; even if, at this stage, the aerospace sector in India is still not highly developed. “TASL endeavors to create a model which is sustainable and replicable”. The push to comply with the Tata Group value system exerts a strong influence on the TASL development and growth path.

For Airbus, another important should-be CSR external driver is the natural environment deterioration, which pushes sustainability to one of the top positions in the respondents’ minds. This emphasizes the need to pursue production and management changes towards a clean and decarbonized aerospace industry. Even though sustainability is also reported among the most influential should-be drivers by TASL, this driver is not found in the TASL website activities or objectives. This commitment towards a clean and green industry could represent an opportunity for TASL and other fast-growing industries, which could incorporate the principles, tools and methods that would enable them to undertake green management practices. Both company strategy (primary reason) and legitimation would support the adoption of an environmental CSR focus [

33].

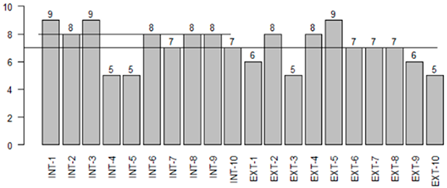

5.4. Discussion of the Current (as-Is) State for CSR Barriers

The radar graphic in

Figure 4 depicts the median survey scores, in the current, as-is situation, for the various CSR barriers in Airbus and TASL, drawing data from

Table 5 and

Table 9.

As depicted in the radar graph, and highlighted by the existence of statistically significant differences between Airbus and TASL in the survey results for seven out of the ten barriers (

Table 13), the two organizations must overcome different hurdles to further advance in CSR. In TASL, the main barrier is related to its smaller size, coupled with an implicit assumption that CSR is better suited for large companies, and the associated resource-related issues, mainly time and economic resources. By contrast, in Airbus the issues primarily stem from the current predominance of a business case assessment approach that does not incorporate sustainability; therefore, a change in the managers mindset would be required for CSR to be integrated into the business core. A complementary approach to get around these stumbling blocks is to make a compelling business case for the business potential of effectively incorporating sustainability.

In the case of the barriers, no survey questions on the “desired” (“should-be”) state were included, for obvious reasons. During the interviews, participants from both companies were adamant that existing barriers should be removed, in order that CSR advancement is not stymied.

TASL interviewees highlighted challenges related to the fast growth of the firm, since it is relatively new in the sector in India. These growth-related challenges included stakeholder alignment, the financial strength required to undertake the desirable projects and the hurdles faced while involving diverse staff in the prioritization decisions to allocate the limited available resources. Airbus participants, while concurring with the existence of such barriers, also emphasized other aspects, such as the cost of technical maturity (in the sense of environmentally friendly products) and the long-term nature of the return of these investments. In Airbus, a culture mindset better tuned to long-term engagement was deemed necessary. This cultural shift might facilitate the increase in budget, training, competences and knowledge required to foster the CSR strategy and reposition CSR as a source of competitive advantage. This might lead to CSR investments being perceived as potential routes to both better overall financial results and quick wins with governments and societal expectations. Interviewees contended that sustainability should be viewed as an opportunity rather than a burden: enabling the development of new or improved products and services (as opposed to the compliance approach of doing it because it is a legal obligation), attracting and keeping increasingly scarce talent, avoiding fines and gaining the support of relevant pressure groups. They also suggested the inclusion of CSR and sustainability topics in the job descriptions of employees, as an incentive to focus more skilled resources on these strategic ambitions. A specific reference was made to the particularly short (three years) terms for Airbus CEO and the board of directors, and how this could be balanced with the required long-term vision and focus.

6. Conclusions

Having established this research project’s general objectives, as well as the specific hypothesis (H1, H2) to be tested, and the ensuing methodology to attain them, in the preceding sections the observed results have been presented, compared and discussed.

In this concluding section, the stated general objectives and hypothesis will be reviewed, in light of the project’s findings. The main conclusions and contributions that derive from these findings will then be analyzed.

Given the specificities of the chosen methodology (in-depth case studies complemented by statistical analysis of survey results), the potential applicability of these findings to other companies and sectors will then be explored. The ultimate aim of this reflection will be to identify how other CSR stakeholders (companies, authorities, researchers, etc.) could benefit from this endeavor’s various facets (methodologies, results including checklists, conclusions, etc.), as well as the corresponding caveats.

Regarding the hypotheses:

H1:The main type of CSR drivers at Airbus and TASL are internal, not external.

H2:The main CSR driver at Airbus and TASL is the personal moral values of the top management.

It is worth reminding that, rather than being self-standing, binary questions, they were set in the context of (and as a first step towards) the project’s general objectives (reviewed below). Furthermore, they were aimed at making specific contributions to the current CSR debate on two major controversies: the relative weight of internal vs. external determinants and the profit vs. moral driven orientation.

Thus, regarding H1 and the relative weight of internal vs. external determinants, the findings of this research support (and qualify) the currently predominant view among CSR scholars: the superior role of internal drivers as compared to the external ones [

26,

39]. When asked about the desired, should-be state, respondents from both Airbus and TASL primarily espoused internal drivers, both through the survey (4 out of the top 5 positions in Airbus and a conclusive 5 out of 5 in TASL are internal drivers), and particularly through the contributions during the structured interviews, as reviewed in the Results section.

The “qualification”, and a prelude to the more general analysis along the various study dimensions carried out below, stems from the gap between Airbus and TASL participants regarding the internal vs. external relative weight in the “as-is” drivers. As discussed in the previous section, and visually highlighted in

Figure 2, the statistically significant differences found between Airbus and TASL are basically due to this difference. As extensively discussed there, the overwhelming dominance of internal drivers in TASL’s as-is state (all the top six drivers were internal) might be attributable to culture-related issues linked to India’s (and Tata’s) cultural heritage. By contrast, the European firm Airbus, framed in a developed economic zone subject to intense competition, and where cultural internalization of CSR’s strategic role is still incipient, is still currently focused on resource-related drivers; three out of the top five as-is CSR drivers are external.

Thus, these findings provide conditional support to H1, particularly in terms of the foreseeable future evolution, with the caveat that, contingent on cultural issues, many firms may not have reached this state yet.

As for H2 and the profit vs. moral driven orientation debate, the outcome is similar to the H1 case. The findings of this research also provide qualified support for the view held by numerous scholars, who emphasize the role of the personal core values of top management and founding entrepreneurs [

22,

23,

24]. As with H1, but to a larger extent, when prompted about the should-be situation, respondents from both Airbus and TASL earnestly highlighted the paramount importance of the personal moral values of the top management. This was conspicuous both in the survey (this driver topped the list in both companies), and throughout the interviews, as analyzed in the Results section.

The study of the current, as-is situation revealed a noteworthy parallelism with the H1 analysis. A discernible gap is also observable here, between the culturally-conditioned TASL, where top management values were also reported as the most influential as-is driver, and the business-case, resource-oriented Airbus, where it lingers in the 8th position.

Thus, following a similar reasoning line, these findings also provide qualified support to H2, quite strongly as it concerns the desirable, should-be state. Nevertheless, an equivalent forewarning should be made about the current state, since, contingent on cultural issues, many firms may also not have completed this evolutionary path yet.

This recurring pattern lends further plausibility to the abovementioned potential key influence exerted by the company’s and the environment’s culture and cultural heritage.

Regarding the project’s general objectives:

To bridge the identified research gap by exploring CSR drivers and barriers in the context of a specific industrial sector (aerospace and defense), and supporting a structured comparison of the results found along the various study dimensions (e.g., current vs. desired states or developed vs. developing markets). This should contribute to a better understanding of the particularities of these dimensions and of facets such as the company’s and the environment’s culture.

The preceding hypotheses-centered analysis already provides significant insights into such aspects as the role of the company’s and the environment’s culture and development state, and on the relationship between the current and the future desired or should-be situations.

Furthermore, the project’s findings suggest that, in terms of CSR drivers and barriers, the current situation could be characterized as contingent, transitional and convergent.

The “contingent” trait, in the sense that the current state of CSR affairs is highly heterogeneous, and contingent on a number of internal and external circumstances, is appropriately illustrated by the statistically significant gap found between the as-is states of Airbus and TASL, both for drivers and for barriers.

This gap, and the likely underlying internal and external circumstances that can explain it for the case of Airbus and TASL (e.g., company size, development state, cultural environment, cultural heritage, etc.), have been discussed at length in the previous section.

The inherent strengths of the methodological approach chosen (in-depth case studies complemented with surveys) have enabled a profound study of these differences and their likely causes, that might provide a starting ground for similar analysis in other companies and sectors. On the other hand, its inherent limitations (since only two companies of the same sector were studied) impede the direct generalization of the specific relationships found. The authors feel, however, that the general conclusion regarding the current heterogeneity and contingency is likely to be widely applicable. As for the specific contingency relationships proposed in this article, they could be used as starting hypotheses to be tested, particularly in similar companies and sectors. At a minimum, the methodology followed in this paper could be used to guide subsequent equivalent analysis, e.g., by providing tried-and-tested templates and checklists for the drives and barriers to be explored.

The “transitional” trait, in the sense that CSR is currently in a state of flux along an evolutionary path, is analogously appropriately illustrated by the statistically significant differences found between the as-is and the should-be states of both Airbus and TASL, as analyzed in depth in the Results section. Based on the similarity of the results found in these two significantly disparate companies, and on the nearly unanimous level of agreement on this particular facet displayed by the various participants, it could be inferred that this attribute will also be found in a generality of companies. This insight could be particularly useful both for researchers and for practicing managers, since it involves a cautionary tale regarding placing excessive emphasis on the observable current situation while analyzing or taking future-oriented decisions.

It is, however, the “convergent” trait that emerges as the most intriguing and potentially consequential finding of this research project. As already hinted at during the previous discussion of the hypotheses, in spite of the remarkable differences between the internal and external circumstances of Airbus and TASL and between their current CSR situations, their projected evolutions are strikingly similar. Based on current trends and on the participant’s testimonies, this cannot be attributed to a foreseeable convergence in their currently disparate circumstances. Rather, it seems to reflect a certain commonality in CSR’s foreseeable evolutionary path, converging on such aspects as the predominance of the internal drivers, the ever-increasing role of the value system and of the shared, internalized company culture and the evolution of CSR’s role from an obligation to a potential source of competitive advantage.

Given the abovementioned methodology limitations, such a remarkable, wide-ranging conclusion should be taken with the adequate precautions. Even though the conspicuousness of the supporting evidence and the disparateness of the two companies under study provide a compelling case for this finding to be credibly extended to other companies within the same sector, it is conceivable that it is influenced by the idiosyncrasy of the aerospace and defense sector (even though the authors have not identified any specific reason suggesting that).

In any case, this insight could represent a useful contribution for the various CSR stakeholders (companies, authorities, researchers, etc.). Official authorities keen on promoting CSR and sustainability could explore whether this convergence is actually noticeable within their target groups, and adapt their policies accordingly. Practicing managers could get a hint of an at least reasonable, maybe even likely, path of future evolution for their CSR activities; on the other hand, if their current plans are at odds with this projection, maybe it would be worthwhile for them to reexamine their assumptions (as if a benchmarking exercise had revealed profound differences with others). As for researchers, the potential existence of a convergent CSR evolutionary path could constitute a promising avenue of research, e.g., by validating this project’s findings, following a similar research methodology, particularly in other industrial sectors.