When Bad Becomes Good: The Role of Congruence and Product Type in the CSR Initiatives of Stigmatized Industries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Congruence between the Company and Cause

2.2. Attribution of Corporate Motives, Credibility, and Attitude

2.3. CSR Initiative Type

2.4. Product Type

3. Study 1: Effects of Congruence and CSR Type on Consumer Response

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.1.2. Pretests and Stimuli

3.1.3. Measures

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Effects of Congruence

3.2.2. Effects of CSR Type

3.2.3. Interaction Effects of Congruence and CSR Type

4. Study 2: Effects of Congruence and Product Type on Consumer Response

4.1. Materials and Methods

4.1.1. Sample and Data Collection

4.1.2. Pretests and Stimuli

4.1.3. Measures

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Effects of Product Type

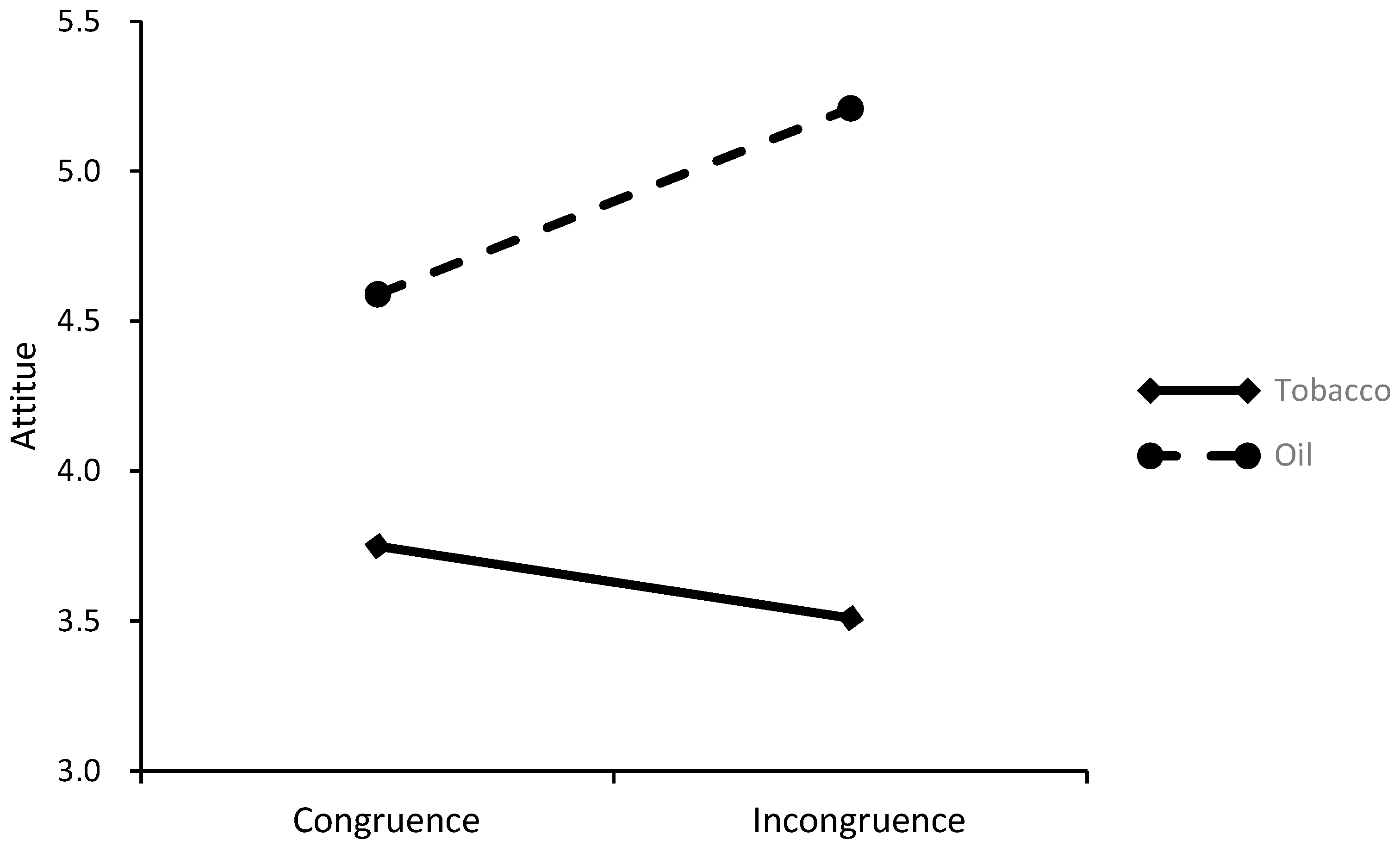

4.2.2. Interaction Effects of Congruence and Product Type

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robinson, S.; Wood, S. A “good” new brand—What happens when new brands try to stand out through corporate social responsibility? J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Business School Online. 15 Eye-Opening Corporate Social Responsibility Statistics. Available online: https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/corporate-social-responsibility-statistics (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Digital Media Solutions. Promoting Social Responsibility Initiatives Can Help Brands Connect with Gen Z Consumers. Available online: https://insights.digitalmediasolutions.com/articles/socially-responsible-brands-gen-z (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Cai, Y.; Jo, H.; Pan, C. Doing well while doing bad? CSR in controversial industry sectors. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quilliam, E.T.; Rifon, N.J. Happy Meals, Happy Parents: Food Marketing Strategies and Corporate Social Responsibility; American Academy of Advertising: San Mateo, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Song, B.; Wen, J.; Ferguson, M.A. Toward effective CSR communication in controversial industry sectors. J. Mark. Commun. 2020, 26, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqueveque, C.; Rodrigo, P.; Duran, I.J. Be bad but (still) look good: Can controversial industries enhance corporate reputation through CSR initiatives? Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2018, 27, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Bae, J.; Kim, S.J. Can sinful firms benefit from advertising their CSR efforts? Adverse effect of advertising sinful firms’ CSR engagements on firm performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Wen, J. Online corporate social responsibility communication strategies and stakeholder engagements: A comparison of controversial versus noncontroversial industries. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Willness, C. Consumer reactions to the decreased usage message: The role of elaborative processing. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Gurhan-Canli, Z.; Schwarz, N. The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on companies with bad reputations. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.; Ferguson, M.A. Are high-fit CSR programs always better? The effects of corporate reputation and CSR fit on stakeholder responses. Corp. Commun. 2019, 24, 471–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDaniel, S.R. An investigation of match-up effects in sport sponsorship advertising: The implications of consumer advertising schemas. Psychol. Mark. 1999, 16, 163184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K.; Eaton, J. Building brand image through event sponsorship: The role of image transfer. J. Advert. 1999, 28, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, C.J.; Becker-Olsen, K.L. Achieving marketing objectives through social sponsorships. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menon, S.; Kahn, B.E. Corporate sponsorships of philanthropic activities: When do they impact perception of sponsor brand? J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandon, P.; Wansink, B.; Laurent, G. A benefit congruency framework of sales promotion effectiveness. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. Charitable programs and the retailer: Do they mix? J. Retail. 2000, 76, 393–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Goldsmith, R.E. Corporate credibility’s role in consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions when a high versus low credibility endorser is used in the ad. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, D.Z.; Herr, P.M. Dangerous donations? The effects of cause-related marketing on charity attitude. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2003, 11, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Trimble, C.S.; Choi, S.M.; Rifon, N.J. Advice for industries: The case for stigmatized products in cause brand alliances. In American Academy of Advertising. Conference. Proceedings; Richards, J.I., Ed.; American Academy of Advertising: Reno, NV, USA, 2006; pp. 253–285. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Viera, E.T., Jr. Striving for legitimacy through corporate social responsibility: Insights from oil companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.L. Causal schemata and the attribution proves. In Attribution: Perceiving the Causes of Behavior; Jones, E.E., Ed.; General Learning Press: Morrstown, NJ, USA, 1972; pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Fein, S.; Hilton, J.L.; Miller, D.T. Suspicion of ulterior motivation and the correspondence bias. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 13, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forehand, M.R.; Grier, S. When is honesty the best policy? The effect of stated company intent on consumer skepticism. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A. A typology of consumer responses to cause-related marketing: From skeptics to socially concerned. J. Public Policy Mark. 1998, 17, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifon, N.J.; Choi, S.M.; Trimble, C.S.; Li, H. Congruence effects in sponsorship: The mediating role of sponsor credibility and consumer attributions of sponsor motive. J. Advert. 2004, 33, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drumwright, M.E. Company advertising with a social dimension: The role of noneconomic criteria. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friestad, M.; Wright, P. The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hastie, R. Causes and effects of causal attribution. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Lafferty, B.A.; Newell, S.J. The impact of corporate credibility and celebrity on consumer reaction to advertisements and brands. J. Advert. 2000, 26, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Lutz, R.J. An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. J. Mark. 1989, 53, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.J.; Haley, E.; Yang, K. The role of organizational perception, perceived consumer effectiveness and self-efficacy in recycling advocacy advertising effectiveness. Environ. Commun. 2019, 13, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H. How CSR Leads to Corporate Brand Equity: Mediating Mechanisms of Corporate Brand Credibility and Reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, O.S.A.C.; Lee, J. The mediating effects of message agreement on millennials’ response to advocacy advertising. J. Mark. Commun. 2020, 26, 856–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D.H. Consumer perception of corporate donations: Effects of company reputation for social responsibility and type of donation. J. Advert. 2004, 32, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Austin, L. Effects of CSR initiatives on company perceptions among Millennial and Gen Z consumers. Corp. Commun. 2019, 25, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Best of breed: When it comes to gaining a market edge while supporting a social cause, ‘corporate social marketing’ leads the pack. Soc. Mark. Q. 2005, 11, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadarajan, P.R.; Menon, A. Cause-related marketing: A coalignment of marketing strategy and corporate philanthropy. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koschate-Fischer, N.; Hoyer, W.D. When will price increases associated with company donations to charity be perceived as fair? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X.; Heo, K. Consumer Responses to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Initiatives: Examining the Role of Brand-Cause Fit in Cause-Related Marketing. J. Advert. 2007, 36, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, B.; Kwon, W.S.; Forsythe, S. Creating effective cause-related marketing campaigns: The role of cause-brand fit, campaign news source, and perceived motivations. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2012, 30, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.P. Modeling strategic management for cause-related marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2009, 27, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, E.C.; Holbrook, M.B. Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. J. Mark. 1982, 46, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strahilevitz, M.; Myers, J.G. Donations to charity as purchase incentives: How well they work may depend on what you are trying to sell. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerman, M.H.; Tenbrunsel, A.E.; Wade-Benzoni, K. Negotiating with yourself and losing: Making decisions with competing internal preferences. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, R.; Wertenbroch, K. Consumer choice between hedonic and utilitarian goods. J. Mark. Res. 2000, 37, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian. Is It Just Fast Food—Or Is It Social Breakdown on a Plate? Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jul/26/fast-food-social-breakdown-takeaway-life-expectancy-society (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Voss, K.E.; Eric, R.S.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, E. Corporate social responsibility as stakeholder engagement: Firm–NGO collaboration in Sweden. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Time, The Tobacco Giant That Won’t Stop Funding Anti-Smoking Programs for Kids. Available online: https://time.com/6147912/altria-anti-tobacco-funding/ (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- The Wall Street Journal. Study Slams Philip Morris Ads That Tell Teens Not to Smoke. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB1022614306124769120 (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Forbes. The Growing Importance of Social Responsibility in Business. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2020/11/18/the-growing-importance-of-social-responsibility-in-business/?sh=2e73eae62283 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Khatib, S.F.; Abdullah, D.F.; Elamer, A.A.; Abueid, R. Nudging toward diversity in the boardroom: A systematic literature review of board diversity of financial institutions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiberg, D.; Rogers, J.; Serafeim, G. How ESG Issues Become Financially Material to Corporations and Their Investors. Harv. Bus. Sch. Account. Manag. 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3482546 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Zamil, I.A.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Jamal, N.M.; Hatif, M.A.; Khatib, S.F. Drivers of corporate voluntary disclosure: A systematic review. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Self-Serving | Altruistic | Credibility | Attitude | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congruence | CRM | 6.21 (0.72) | 2.73 (0.89) | 3.51 (0.93) | 3.99 (1.00) |

| Advocacy | 6.08 (0.79) | 2.99 (0.87) | 3.44 (1.04) | 4.01 (0.93) | |

| Incongruence | CRM | 5.92 (1.11) | 3.27 (0.79) | 4.11 (0.82) | 4.37 (0.83) |

| Advocacy | 6.11 (0.70) | 3.13 (1.07) | 3.79 (1.24) | 4.53 (1.24) |

| Self-Serving | Altruistic | Credibility | Attitude | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congruence (C) | 0.67 | 4.07 * | 6.60 * | 5.81 * |

| CSR Type | 0.04 | 0.12 | 1.09 | 0.24 |

| C × CSR Type | 1.06 | 1.35 | 0.47 | 0.17 |

| IVs | DVs | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Congruence (C) | H1a | Self-Serving Motive | Not Supported |

| H1b | Altruistic Motive | Supported | |

| H1c | Credibility | Supported | |

| H1d | Attitude | Supported | |

| CSR Type | H2a | Self-Serving Motive | Not Supported |

| H2b | Altruistic Motive | Not Supported | |

| H2c | Credibility | Not Supported | |

| H2d | Attitude | Not Supported | |

| C × CSR Type | H3a | Self-Serving Motive | Not Supported |

| H3b | Altruistic Motive | Not Supported | |

| H3c | Credibility | Not Supported | |

| H3d | Attitude | Not Supported |

| Self-Serving | Altruistic | Credibility | Attitude | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congruence | Hedonic | 5.44 (0.16) | 2.59 (1.07) | 3.05 (0.22) | 3.75 (1.24) |

| Utilitarian | 6.10 (0.16) | 3.49 (0.97) | 3.71(0.22) | 4.59 (0.97) | |

| Incongruence | Hedonic | 5.27 (0.16) | 3.00(0.99) | 3.26 (0.22) | 3.51 (0.13) |

| Utilitarian | 5.77 (0.15) | 4.12 (1.13) | 4.55 (0.22) | 5.21 (1.16) |

| Self-Serving | Altruistic | Credibility | Attitude | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Type | 13.84 ** | 27.93 *** | 19.82 *** | 34.59 *** |

| C × Product Type | 0.24 | 0.35 | 2.07 | 3.90 |

| Product Type | H4a | Self-Serving Motive | Not Supported |

| H4b | Altruistic Motive | Supported | |

| H4c | Credibility | Supported | |

| H4d | Attitude | Supported | |

| C × Product Type | H5a | Self-Serving Motive | Not Supported |

| H5b | Altruistic Motive | Not Supported | |

| H5c | Credibility | Not Supported | |

| H5d | Attitude | Marginally Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. When Bad Becomes Good: The Role of Congruence and Product Type in the CSR Initiatives of Stigmatized Industries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138164

Kim Y, Choi SM. When Bad Becomes Good: The Role of Congruence and Product Type in the CSR Initiatives of Stigmatized Industries. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):8164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138164

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yoojung, and Sejung Marina Choi. 2022. "When Bad Becomes Good: The Role of Congruence and Product Type in the CSR Initiatives of Stigmatized Industries" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 8164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138164

APA StyleKim, Y., & Choi, S. M. (2022). When Bad Becomes Good: The Role of Congruence and Product Type in the CSR Initiatives of Stigmatized Industries. Sustainability, 14(13), 8164. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138164