Abstract

Mandatory corporate extraterritorial responsibilities to promote environmental, social and human rights awareness and recordkeeping have been criticised as green-washing, despite the progressive intent of such attempts. This article conducts an in-depth investigation of extraterritorial responsibility through the lens of the social licence to operate (SLO), using a hybrid methodology involving doctrinal, conceptual, black letter, interdisciplinary and socio-legal sources. We aim to give an overview of decided cases referred to the Supreme Court by the Court of Appeal, in the hope of offering academic groundwork for legalising corporate extraterritorial responsibility in the context of global value chains with the participation of multinational enterprises and various stakeholders, including those in very vulnerable positions in developing or the least developed countries. Previous research on the notion of the SLO has tended to focus on one particular industry, based on the assumption that an SLO is more relevant in corporate social responsibility (CSR)-sensitive sectors. This article will change the focus and aim to answer the question of whether building and maintaining SLOs can help companies to acquire the social legitimacy to fulfil extraterritorial social responsibility. We link the goals, ideals and breadth of SLOs to those of extraterritorial responsibility in order to provide supplementary support for legislators to achieve better compliance and risk management. We conclude that the benefits of seeking an SLO are that they can help to inform progressive extraterritorial legislative attempts, promote board accountability, and mitigate environmental and social risks.

1. Introduction

The investigation of mandatory extraterritorial responsibilities rests critically on the responses to two key theoretical enquiries: could and should SLOs be used to explain the significance and legitimacy of corporate extraterritorial responsibilities to enhance the compliance of extraterritorial responsibilities and to resolve conflicts between the vulnerabilities of stakeholders and the power of MNEs, in order to create more sustainable business and social environments? This article aims to contribute an academic basis to rationalise mandatory corporate extraterritorial responsibility through the lens of the SLO. We make a connection between the goals, ideals and breadth of SLOs and those of extraterritorial responsibility, in order to provide supplementary support for legislators to achieve better compliance and risk management.

1.1. Research Significance

This is a significant attempt with comprehensive application to the reconciliation of the shareholder-centred values of MNEs and the interests of multiple stakeholders, in the context of the trend towards sustainable and ethical corporations. The article offers a valuable contribution to the literature on stakeholder engagement, social cohesion and sustainable economic development. In detail, the significance of the article rests on the following two aspects.

First, the analysis hopes to contribute to vulnerable community engagement, economic well-being and social cohesion by supporting directors of all kinds of companies to have a better understanding of the rationales and legislative approaches underlying the creation and maintenance of SLOs as well as protecting extraterritorial stakeholders, particularly vulnerable ones such as local communities and substitutable employees. Second, the links between extraterritoriality and SLOs will support policymakers to design additional legislative approaches more confidently, reducing the risk of negligent corporate actions by MNEs outside their territory and offering a measure of protection for extraterritorial stakeholders.

1.2. Research Originality and Novelty

The article is an original attempt to link SLOs with mandatory corporate extraterritorial responsibility, in order to produce coherent arguments for a more rational and logical embedding of ethical notions in the domain of corporate law with extraterritorial reach. The article brings rigour and rationality to the field of regulating MNEs that are engaging in global business in developing and the least developed countries. Rather than focusing on a particular industry, the article offers a comprehensive and general analysis of mandatory corporate extraterritorial responsibility in a specific business scenario.

1.3. Research Layout

The article proceeds as follows. After the introduction, Section 2 provides an overview of the methodology framework of the article. Section 3 is concerned with the application of corporate extraterritorial responsibility in MNEs, contextualising current legislative attempts. Section 4 critically reviews the literature on SLOs to illustrate the theoretical basis for the practical operation of extraterritoriality in corporate responsibility. Section 5 investigates the links between SLOs and extraterritorial corporate responsibility, in order to shed light on the legitimacy of extraterritorial responsibility. A typical business scenario is presented, referring to recent cases. Links between stakeholder participation, board accountability, risk management and SLOs are also made to further consolidate the rationale for applying SLOs to justify extraterritorial responsibility.

2. Literature Review: Rationale and Challenges for the Regulation of Multinational Enterprises

Governing multinational enterprises (MNEs) in a multilevel world requires novelty and innovation. The adoption of extraterritoriality as a projection of national law abroad, with the legal impact outside the home jurisdiction, is one of the most recent new legal forms to tackle sustainability challenges [1]. However, this approach has not always been positively acknowledged, primarily because of a lack of legislative rationale and enforcement measures. This article will try to address the first concern by examining the notion of the SLO in the context of MNEs’ extraterritorial responsibilities, mainly executed through their boards of directors and required by both company law and soft law approaches such as corporate governance codes.

Despite its laudable intent, mandatory corporate extraterritorial responsibility may be incompatible with traditional notions of state sovereignty [2] and the shareholder primacy norm, which is the default dogma in the UK and the US. The doctrine of separate legal entities, the limited liability principle and the complexity of corporate groups with thousands of subsidiaries create difficulties for the exercise of companies’ extraterritorial responsibility. The transnational structure of MNEs and economic and financial globalisation have blurred the boundaries that determine whether a particular situation or organisation is located in a given territory [3]. The distribution of MNEs’ controlling power has been arranged in ways that challenge territorial boundaries [4], and in practice the complications brought by piercing the corporate veil make the issue even more acute.

Furthermore, the current business culture is steeped in “a standard economic narrative” related to beliefs that corporations are independent legal persons for the purpose of making profits with their nationality decided by their registration [5]. Political barriers such as foreign relationship priorities [4,6], intended to help domestic corporations to secure contracts abroad by lobbying against extraterritorial regulatory [7] and anti-extraterritoriality opinions from courts to advance welfare [8,9,10], also create challenges for legal attempts to impose corporate extraterritorial responsibilities. In the corporate setting in general, but particularly for MNEs, there are important calls for an even distribution of rights and resources such as clean water, safe working conditions, security and health, and access to these rights and resources is often seriously undermined by the misconduct of large corporations.

This situation becomes increasingly complicated in contexts characterised by powerful MNEs in conjunction with poor living and working conditions and environments in developing and the least developed countries. The growing corporate power of MNEs is partially problematic as the result of globalisation, which sometimes deepens vulnerability while diminishing the resilience required to adapt and mitigate it [11]. In the future, companies will increasingly be expected to take on joint responsibility to mitigate vulnerability as a part of the need for public-private partnerships to establish social legitimacy and strive towards global sustainability goals.

In addition to these complications, however, the most challenging issue is that extraterritorial attempts always lack a solid foundation that is widely acceptable to a variety of schools of thought [12,13]. A good notional base for persuasive and plausible arguments for corporate extraterritorial responsibility is vital in order to promote more accountable companies and boards, but also to mitigate corporate risks [14,15,16,17]. This article aims to fill this gap by investigating the notion of the SLO, not only to make extraterritorial responsibility rational and legitimate but also to broaden the understanding of the SLO notion beyond its current context of the mining industry and other CSR-sensitive sectors [18,19,20]. We contextualise a particular business scenario through an analysis of recent cases, and argue in favour of corporate responsibilities to mitigate extraterritorial vulnerability and promote the interests of extraterritorial communities [21]. This scenario involves MNEs, their subsidiaries and the most vulnerable communities and employees.

3. Methodology

This is a desk-based conceptual and analytical piece of legal research (secondary research) primarily based on the material published in reports, journals, book chapters and monographs that are available in the public domain. The authors aim to critically review previous research findings and judgements to gain a comprehensive understanding of the field of corporate extraterritorial responsibility through an original lens, i.e., the SLO. It uses a hybrid methodology comprising black letter, theoretical, interdisciplinary, doctrinal, and socio-legal research. Section 3 and Section 4 of the paper utilise the doctrinal and interdisciplinary approach, and the findings are based on analysing and contextualising relevant legal authorities, primarily statutes and case law. Section 5 of the article employs black letter and interdisciplinary research methods by exploring SLOs through different innovative lenses such as risk management and board accountability. The theoretical investigation formulates the central arguments in the article. Arguments supporting mandatory extraterritorial corporate responsibility and theoretical support for the concept of the SLO are socio-legal, and the extraterritorial social, environmental and human rights impacts of MNEs’ conduct are carefully studied as social phenomena. We aim to understand how the legal idea of the SLO, corporate practices, and MNEs as business institutions are influenced by or function in developing counties with weaker bargaining power, immature legal systems, less effective law enforcement, and more complicated social and political contexts such as a high score on the Corruption Perceptions Index. The socio-legal approach is practical and suitable to articulate an ambiguous concept such as extraterritorial responsibility in its particular social and political context.

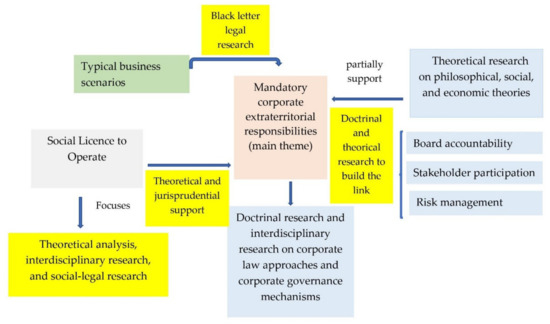

The methodology framework (Figure 1) consists of black letter, theoretical, doctrinal, interdisciplinary and socio-legal research methods applied to the analysis in different parts of the article. First (presented in blue), the framework shows the relationships between mandatory corporate extraterritorial responsibility and current mainstream theories, board accountability, stakeholder participation and risk management. Second (presented in green), it contextualises the typical business scenarios in which mandatory corporate extraterritorial responsibility become particularly important. Third (presented in grey), we examine the connection between SLO and mandatory corporate extraterritorial responsibilities. We have presented the relevant methodologies in yellow.

Figure 1.

The methodology framework.

4. Extraterritorial Corporate Responsibility to Promote Corporate Sustainability

4.1. Treating Multinational Enterprises Differently

The article focuses on MNEs as “a cluster of corporations of diverse nationality joined by ties of common ownership and responsive to a common management strategy” [22], as well as the global value chains they invest in and impact on. With this focus, we pay attention to value chains structured through parent-subsidiary relationships, and to global supply chains structured through contractual relationships. The term “MNE” has also been contested and confused with other terms such as “transnational corporation” or “global corporations”; it is not our goal in this article to differentiate between these terminologies, but it will be valuable to contextualise a few distinct characteristics of MNEs.

First, MNEs own and control assets beyond their national territory. These assets may be also directly owned by their subsidiaries. Therefore, the tort liability of MNEs and their subsidiaries can involve a complicated investigation; for example, a complicated network of legally separated and independent subsidiaries may belong to a single economic unit, and therefore be responsive to board decisions and managerial discretion from a sole decision-making centre [23]. Second, MNEs are always involved in global value chains, and their business impacts suppliers, the employees of suppliers and communities in developing countries. Third, it is increasingly the case that the majority of MNEs place high importance on implementing CSR policies and activities to boost sustainable development with increasingly active participation from stakeholders and communities, so as to attain mutual benefits with regard to profit, merits and moral standards [24].

MNEs have a truly global impact, not just on economic development but also on the environment and society. The Economist reported that MNEs own or orchestrate supply chains that account for over 50% of world trade, although they only account for 2% of jobs worldwide [25]. Due to their complexity and global impact, MNEs may become subjects of international law related to global criminal activity or transitional tort litigation. States compete for investment from MNEs, which provide important financial income for governments. However, this high level of competition may also lead to weak regulatory frameworks and accountability mechanisms, even though MNEs are faced with a wide variety of social, environmental and human rights externalities in their corporate actions. This problem merits consideration in terms of possible approaches to bridge the accountability gap. While voluntary CSR by itself is highly unlikely to solve the most serious sustainability challenges, it makes sense to pursue SLOs from local communities and locate hard law measures in domestic law, using extraterritorial reach to address the typical vulnerabilities of MNEs, considering their characteristics and the market structures in which they operate.

4.2. Regulating Multinational Enterprises through Extraterritorial Corporate Responsibility

Rules in relation to extraterritoriality are one of the most important approaches for MNEs. “Extraterritoriality of regulation has become a fact of life” [10]. This is a “situation in which state powers (legislative, executive or judicial) govern relations of law situated outside the territory of the state in question” [26]. This involves an exercise of jurisdiction by a nation state over behaviours that happen outside its territory [27]; the extraterritoriality examined in a corporate setting is a condition where a state power controls activity in relation to communities or stakeholder relationships beyond its own borders through synchronised business actions.

A fundamental and common feature of extraterritorial jurisdiction and MNEs is their transnational nature. When MNEs are involved in unethical behaviours and extraterritoriality is used to represent the vulnerable during dispute settlement (perhaps because of the inadequacy of national avenues and resources to tackle problems satisfactorily), in most cases to date the extraterritorial approaches have involved attempts to promote sustainability, seek justice and equality, and mitigate vulnerability. This refers to the application of domestic law outside the borders of the jurisdiction of the home state of an MNE or a company with a global supply chain. It arises in a variety of contexts, and imposes extra duties on the boards of these companies. These are imposed as the result of a strong tendency for the need to levy an obligation on states to seek to influence extraterritorial situations to align the scope of the international responsibility of developed states with the degree of their effective power to control [28].

In order to achieve sustainable economic growth, using domestic laws with extraterritorial effect in a transnational attempt to deal with environmental, social and human rights abuses is at the centre of the progressive law reform movement [29]. From the angle of internal governance and the imposition of broader or additional duties upon boards of directors, discussions on extraterritorial responsibility are likely to be required in domestic law where the question of extraterritorial regulation takes on greater relevance.

In detail, the domestic regulatory framework can be observed in legislation such as company law, insolvency law, and laws tackling transnational crimes such as human trafficking and bribery. It is worth pointing out that despite their potential function in combating transnational sustainability challenges, extraterritorial attempts are frequently exceedingly politicised, with nation states using such approaches to further their unilateral foreign policy objectives [30]. This may be seen in strong objections from developed countries in relation to attempts to control the process of globalisation and the regulation of MNEs. This thwarted initiative also makes the imposition of extraterritorial responsibilities on MNEs, which are mostly registered in developed countries, even more legitimate and necessary. In other words, extraterritorial attempts could be seen as “colonialist efforts” in which developed countries take the lead [31] in the establishment of a favourable regulatory framework that nevertheless also applies to the rest of the world.

4.3. Review of the Existing Primary Sources of Extraterritorial Corporate Responsibility

In an effort to promote the principle of “consistent best practice” within the domain of company law, some jurisdictions make legitimate extraterritorial applications to govern the actions of their corporations. Extraterritoriality is an instrument that can be applied to ensure that the environment is protected and human rights are respected by companies and board members in a cross-border context, especially involving MNEs with a strong presence in the least developed nations. However, these attempts have been heavily criticised for their weak theoretical foundations and lack of incentives. The approaches in different jurisdictions also vary, even when they have the same legal system and similar corporate governance models.

One important dimension of the responsibilities of developed states is fulfilled by the board of directors of MNEs who see these developed states as their home states. This can be achieved through imposing transparency requirements in various forms in both transnational and domestic law. Active domestic law approaches include statements such as s.54 of the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015, and a due diligence mechanism enacted in s.7(1) of the UK Bribery Act 2011, which specified a crime where corporations fail to prevent bribery committed by individuals allied with the company.

A duty of vigilance through a mandatory vigilance plan such as art. L. 225-102-4 of the French Code of Commerce provides the steps that MNEs must take to detect risk and prevent human rights violations and environmental damages resulting from the activities of their subsidiaries, suppliers and subcontractors. In addition to the French law, which is regarded as a landmark in enlightened corporate respect for human rights and corporate protection of the environment and society at large [32], the Company Act of Albania is probably the most innovative in terms of group companies, having a broad extraterritorial application [33]. In relation to the fiduciary duties arising in “an equity group”, it is stated that directors of the parent company “must take account of the interests of the subsidiary company” [34]. A director “shall be liable for his actions” for “violation of their duties” [35], and this may be enforced through derivative action by a partner, shareholder or creditor as a private enforcement measure of directors’ duties [36]. Fiduciary duties are thereby extended to form an MNE compliance system with coverage of foreign subsidiaries and stakeholders in the global supply chain.

In addition to attempts in civil law countries, a duty of care within a supply chain was also introduced in common law countries based on the principles established in Candler v Cape [37], which assessed the proximity between an entity and the employee of another entity, as well as the fairness and reasonableness of imposing a duty of care [38]. Principles for common law jurisdiction over extraterritorial acts have mostly advanced within national legal systems. For example, an approach comparable to the “enterprise liability doctrine” [39] is enacted in the United States. The attribution of liability incurred by a subsidiary to a parent entity is recognised due to the “integrated” and coordinated character of corporate groups and enterprises [40]. Australia has adopted a more progressive approach wherein two types of extraterritorial regulation have become legitimate in company law. According to the Australian Corporations Act, each provision of the Act applies to all corporations, including those not having a nationality or territorial connection to Australia [41]. However, statutory directors’ duties do not apply to extraterritorial directors of foreign companies unless a jurisdictional connection can be established [42].

4.4. Contextualising Corporate Extraterritorial Responsibility

Extraterritorial attempts always relate to governments’ claims of being international frontrunners in settling sustainability challenges globally. The goal of extraterritorial sustainability could be achieved through transparency requirements or imposing additional duties upon directors to implement a “vigilance plan” as part of their duties of skill, care and diligence, as well as extended fiduciary duties that strengthen the regulation of unethical conduct. This is applicable in relation to extraterritorial acts or omissions occurring outside the jurisdiction of the relevant legislation. With the involvement and contribution of civil society, the law-drafting process has been developed in favour of more respect for sustainability issues in a globalised context. Companies and directors may be held accountable for their decisions and conduct if they breach their duty of care, steering company law towards a wider convergence with extraterritorial considerations. These broader duties include both an “objective” axis with ethical objects as well as shareholder wealth maximisation, and a “scope” axis along which directors must consider elements of extraterritoriality by including extraterritorial stakeholders’ interests when they make corporate decisions that may internalise sustainability challenges directly and strategically [43]. These extraterritorial attempts may be relevant to violations in developing states in a number of scenarios. Most often, these involve situations where corruption and ineffective government authorities disrupt the availability of juridical recourse within the domestic legal system, or where state departments are themselves responsible for these violations [44].

5. The SLO and the Undertesting SLO in the Global Business Environment

5.1. Definition of an SLO

An SLO is hard to define and impossible to measure [45]. The most influential definition describes the notion as “the demands on and expectations for a business enterprise that emerges from neighbourhoods, environmental groups, community members and other elements of the surrounding civil society” [46]. An SLO reflects the “dynamic and changing quality and strength” of the connection and engagement between corporations and communities or stakeholders, and the lack of an SLO may incur serious delays and costs for corporations.

The term SLO in the business arena has been defined and understood in diverse ways, not least owing to constant fine-tuning of the expectations and demands of stakeholders in dynamic corporate settings, especially those involving MNEs. Focusing on its relationship with stakeholders, the SLO is defined by Black as “the negotiation of equitable benefits and impacts of a company in relation to its stakeholders, over the near and longer term” [47]. More interactively, Thomson and Boutilier contextualise an SLO as existing when a project has continuing acceptance or approval within the local community as well as with a variety of other stakeholders [48]. More practically, a survey of mining industry professionals found that 90% of practitioners viewed an SLO as “an intangible, impermanent indicator of ongoing acceptance of a company’s activities by communities” [49].

The SLO has principally been established within the CSR literature in the context of key themes such as corporate sustainability, corporate citizenship, social and environmental reputation and the legitimacy of CSR, which are seen as essential for companies to build a sustainable relationship with the communities wherein they operate [50]. In a corporate setting, an SLO is not a piece of paper or a government licence. Rather than being a permanent treaty, an SLO is a dynamic social contract that requires renewal and re-evaluation. It is contingent on the dynamic preference perceptions of multiple stakeholders [51], operating as a form of social endorsement that companies can win through responsible and accountable corporate conduct and decisions together with sustainable interactions with various stakeholders, so as to build the perception that the company deserves a valid and fair place in a community [52].

The clarity and scope of the SLO notion depend very much on the investigation of a few issues such as the definition and geographical and contractual scope of the “community”, the relationship between the “community” and local citizens, and how to validate decisions without reaching a consensus on nature and scope of the term “community” [53]. The “community” can be divided into vested communities that would have a voice in awarding an SLO, vested communities who own a right to the possession of tangible items in the community, and nonvested communities who have only a voice [54].

An SLO can be regarded as a contract that is a result of partnering with stakeholders [54]. The SLO is broadly regarded as going beyond compliance with the law; Moore contended that corporations should exceed government regulations in order to maintain their SLO with the public and the community and compensate for government failures, which might produce community opposition later [55]. Key factors of the level of SLOs include trust and perceptions of fairness [56]. The scope of the community is very much decided by geographic proximity to an operation, the level of participation in granting and maintaining the licence, and rights in challenging the legitimacy of the licence [57].

5.2. The Nature and Scope of SLOs

No consensus has been reached about “the demands made by those to whom the social licence is presented or how and when their demands should be responded to” [58]. An SLO is established through engagement with individuals of the local community and information disclosure about corporate decisions and strategic projects, stakeholder communications and stakeholder scrutiny, as well as what may happen in the future [59]. Granting an SLO relies on sustainable relationships with stakeholders based on social legitimacy, credibility and trust as key values for the operation of the social licence [59]. An SLO is much more helpful in comparison with CSR, requiring corporations to ensure that their decisions and behaviours respect the rights of all the members in a given community.

The concept of the SLO is a contractarian base for the legitimacy of a company’s activities or projects [60]. It has become widespread, and therefore warrants closer scrutiny in sectors beyond its traditional applications in the mining industry, where the concept originated [61]. The limited body of research investigating SLOs has tended to draw from SLO experiences and their application generally, but the SLO will be only meaningful as a concept in connection with a specific activity, including “a specific project, policy, law, product, initiative, operation, campaign, or whatever”, and mediated by “NGOs, interest groups, trade unions, religious groups, media and the wider public” [62]. Therefore, our arguments will investigate the SLO literature by linking business scenarios involving the value chain of MNEs with the notion of the SLO, together with an articulation of SLOs’ functions in promoting sustainability, equality and fairness.

In some cases, the conditions required by social licensors may be more demanding than those levied by regulation. This will lead to actions “beyond compliance” in terms of the companies’ environmental, social and human rights objects [46]. The SLO may be used to complement both hard and soft law to achieve extraterritorial justice around the globe. Taking the Ruggie Principle as an example, the most obvious motivation for corporate compliance, according to Ruggie, is that the responsibility to respect will be supported by the “court of public opinion” [63], as part of the social expectations imposed on companies or a condition of an SLO [58]. The “court of public opinion” will enable communities to execute “naming and shaming” powers over social operators that do not conform to social expectations. Ideally, courts of law and the court of public opinion will be balanced to ensure the accountability of MNEs [63], and SLOs will help corporations to embrace and embody not only the law’s formal remit by complying with command-and-control regulation, but also the spirit of the law by self-regulation through voluntary codes of conduct [19].

5.3. The Purpose, Function and Classification of an SLO

As for the purpose of an SLO, it is generated and developed to control and minimise the negative impact of social problems such as child labour and environmental pollution and degradation. When an SLO is used to promote more socially responsible companies, profit growth can be seen as a by-product [64]. The SLO is an increasingly popular tool for corporations to establish and manage long-term and sustainable relations with communities. The SLO will also facilitate profit-making if the companies are granted an SLO to extract natural resources, and companies may even obtain the general public’s acceptance and even approval of corporate activities [64].

The SLO is essentially a political idea related to the distribution of benefits and impacts, and its withdrawal is often a political decision that aims to change public policy [64]. The SLO functions as a safeguard against corporate misconduct, on the basis of adequate trust, legitimacy, and the consent of stakeholders who are affected by the behaviour. Due diligence for preserving the SLO often involves accumulating social capital in a procedure that is recognised as community- and capacity-building as well as institutional-strengthening [53]. If corporations can obtain an SLO, they will obtain the privilege of operating with minimal formalised restrictions built on established public faith, which indicates that society trusts that the activities of the corporations will be in line with social expectations and the values of the local community [65].

Together with a right to operate that is legally granted by the state, based on concession theory [66], the SLO functions as a spectrum of multiple social licences for companies to operate, obtained from various societal groups [67]. Establishing an SLO will promote sustainability and stakeholder interests, while also potentially reducing economic risks for the company since it mitigates the risk of group actions at production sites. Although an SLO indicates an encouraging relationship between corporations and their communities and stakeholders, corporations are hardly keen to withdraw operations when impacted stakeholders or communities are in opposition [68]. The positive impacts of an SLO can be observed from engagement with a community, the community’s access to critical information, and enhanced stakeholder scrutiny. The SLO facilitates public cooperation and compliance as communities and stakeholders not only know about corporate decisions and policies, but also understand the rationale underlying them [69].

Rather than being a binary concept, e.g., a company either has or does not have one, the SLO is about multifaceted social relationships and should be conceptualised as “a continuum of distinguishable levels” [70]. The SLO is a much more useful concept than CSR is in terms of its enforceability and effectiveness, as the SLO requires corporations to ensure their actions respect the rights of all community members [71]. The notion of the SLO will facilitate and encourage external regulation to promote CSR, in order to advance the long-term interests of society and sustainability. Compared with a legal licence issued by a governing authority, the SLO needs to be earned from impacted stakeholders and the community [72].

As for the classification of the SLO, Joyce and Thomson associated SLOs with the idea of social risk and corporate reputation, and articulated that granting an SLO requires that a company must be perceived as legitimate [73]. The legitimacy of modern corporations as business institutions is an important assumption in society—their SLO depends on their capability to satisfy the expectations of a complicated and assorted array of community members, particularly for MNEs [74]. Thomson and Joyce introduced different levels of SLOs, including the lowest level of basic “acceptance”, which only requires being regarded as legitimate, a developed level of “approval” that may be gained if corporate actions are seen as credible, and the highest level that comprises insights of trust [75].

6. Linking the SLO with Extraterritorial Corporate Responsibility

The emergence of the concept of the SLO indicates increasing corporate awareness of the need to communicate with community members in terms of benefits and costs of industrial development [61]. The operation of a social licence involves the maintenance of essential goods ranging from clean drinking water to vaccines, and from eliminating modern slavery to fighting gender discrimination. In this section, a number of factors that are related to establishing and maintaining a social licence are discussed, such as transparency, accountability and effectiveness [62]. We explore the question of how the SLO notion is instantiated through the lens of stakeholder engagement as an extension of CSR.

6.1. Typical Business Scenarios with the Participation of MNEs: A Review of Recent Cases

It is an open secret that in many cases the business activities of large companies carried out through foreign-domiciled subsidiaries in developing countries involve human rights violations and environmental hazards that compromise the well-being of the most vulnerable local communities. Fighting against these abuses in the host country is not easy due to factors such as political interference, mistrust of the courts, inability to afford legal assistance, lawyers’ lack of experience, and so on [76,77]. In these cases, the only viable option for the affected groups is often to litigate in the home state of the partner company [78]. The problem is that traditionally this sort of claim is rejected on the basis of limitations imposed by tort law and domestic rules [79].

The situation changed radically after a ruling by the UK’s Supreme Court in the case of Vedanta Resources PLC and Another v. Lungowe [80], where it was confirmed that civil claims against an English parent company, e.g., Vedanta, together with the Zambian subsidiary (KCM) for damages in Zambia could proceed before the English courts [81]. The plaintiffs—a group of 1826 persons who live in the Chingola District in Zambia—alleged that the operations of KCM in the Nchanga copper mine had polluted their only source of water for personal consumption and irrigation, resulting in damage to their health and farming activities [80]. The claims against both defendants were pleaded in common law negligence and breach of statutory duty in the case of KCM because it was the operator of the mine, while the claim against Vedanta arose by reason of the “very high level of control and direction that the first defendant exercised at all material times over the mining operations of the second defendant and its compliance with applicable health, safety and environmental standards” [80].

The court addressed two issues, the first of which turned on whether Vedanta had intervened sufficiently in managing the mine possessed by its subsidiary KCM to have itself incurred duty of care to the claimants. Lord Briggs ruled that the parent may incur a duty of care in responding to third parties if it holds itself out as exercising that degree of supervision and control of its subsidiaries in published materials [80].

Second, the Supreme Court considered whether the claims could be heard before English courts. Although the proper place to do so would be Zambia, the Court held that if there is satisfactory evidence of an actual risk that substantial justice will not be attained in an extraterritorial jurisdiction, it might give permission to a foreign defendant to bring litigation in England [82]. It was concluded that access to justice was not available in Zambia due to two factors: first, the fact that the claimants lived in extreme poverty and could not afford the costs of the process; second, the absence of appropriately knowledgeable legal teams within Zambia to initiate effective litigation, considering the size and complexity of the case to be prosecuted [80].

Although the circumstances under which a parent company could owe a legal duty of care to the employees of its subsidiaries had already been enunciated in Chandler v. Cape [37,83,84], the decision in Vedanta constitutes an important precedent for providing access to justice for foreign claimants [79]. This new trend has been followed by other jurisdictions such as the Netherlands [85] and Canada [86], and it is expected to have an impact on companies’ willingness to implement human rights and environmental policies, as well as to actively supervise the operations of their subsidiary companies [87].

It is worth noting that the approach of the English courts was not the same in the case of Okpabi v. Royal Dutch Shell [88]. Here, the claimants—citizens of Nigeria—claimed that Royal Dutch Shell Plc, a UK company and the parent company of the multinational Shell group of companies, owed a duty of care to the people of the Ogale community who had been affected by the contamination of natural water sources due to the negligence of the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd. (Rivers, Nigeria). This company, which is a subsidiary of RDS, was alleged to be responsible for oil spills causing widespread environmental damage and not adopting adequate remedial measures [88].

To determine whether Royal Dutch Shell owed a duty of care, the Court focused on the proximity requirement to “control operations”. In this regard, Lord Justice Simon pointed out the importance of distinguishing:

“Between a parent company which controls, or shares control of, the material operations on the one hand, and a parent company which issues mandatory policies and standards which are intended to apply throughout a group of companies in order to ensure conformity with particular standards. The issuing of mandatory policies plainly cannot mean that a parent has taken control of the operations of a subsidiary (and, necessarily, every subsidiary) such as to give rise to a duty of care in favour of any person or class of persons affected by the policies” [88].

After the analysis of five factors taken into account to determine the relation of proximity [89], it was concluded that there was no sufficient degree of control of operations of the Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd. by Royal Dutch Shell to build the required degree of proximity [88]. A duty of care does not merely arise because of health and safety guidelines introduced by the parent company, which should apply to all subsidiaries [90].

However, the last word in this matter is yet to be uttered [76]. Recently, the English Supreme Court granted permission to appeal in the understanding that the Court of Appeal had made various errors of law, including an approach to the factors and circumstances that might give rise to a duty of care that was inconsistent with that taken in the Vedanta case [87]. Thus, it may be expected that the new judgement will follow the same path, in line with the purpose of ensuring rigorous compliance with ethical requirements.

The typical business scenario where corporate extraterritorial responsibility is triggered involves the participation of MNEs, their subsidiaries and vulnerable and uninformed stakeholders in developing and the least developed countries. In this scenario, an SLO enables companies to implement upgraded social and environmental practices that go beyond regulatory compliance [91]. SLOs assume a quasi-contracultural connection between the company and society, where the terms of supply and demand have been reciprocally accepted [91]. This quasi-contract specifies the terms and conditions under which companies are granted an SLO. If these terms and conditions are breached, e.g., by noncompliance with the SLO, the withdrawal of the licence is considered an important reminder of the recognition, maintenance and enforcement of the SLO. In this business scenario, licensors include parties or entities that can grant an SLO, such as governments or landowners in the local community, while licensees are companies that are obliged to comply with the conditions of their prospecting SLO.

6.2. Enforcement of Extraterritorial Responsibility and Stakeholders’ Participation

In order to attain local fairness, MNEs need to be able to access privileges in a state while bearing the burden of being held accountable. The enforcement of extraterritorial sustainability challenges is key for their legitimacy. It may encompass the efforts of all community members, through private enforcement measures assisted by public enforcers both nationally and internationally. It may be valuable here to give examples from the perspectives of both private enforcement and public enforcement, in order to clarify the importance and application of effective corporate extraterritorial responsibility mechanisms.

From the point of view of private enforcement, extraterritorial responsibilities require sharing corporate resources through extra duties by considering the interests of multiple stakeholders, including extraterritorial ones. One legislative attempt using this logic is s.1324 of the Australian Corporations Act, which allows “a person whose interests have been, are or would be affected by the conduct” of the director breaching the Section to seek an injunction [92]. The section may serve as a remedy for stakeholders and community members, including those of MNEs’ subsidiaries or suppliers [93].

Teamwork is also supported by institutions at the international level. The International Chamber of Commerce encourages governments to use intergovernmental organisations such as the OECD as vehicles for resolving problems and disputes in relation to the extraterritorial application of national law, through processes of consultation, cooperation, conciliation or arbitration [94]. Moreover, states are encouraged to foster convergence and the harmonisation of divergent national laws and policies to recognise equivalent standards. Effective extraterritorial regulation needs active participation from stakeholders, corporations, nongovernment organisations and states. As well as the contribution of independent international organisations, MNEs’ extraterritorial responsibility requires harmonisation, collective accountability and answerability that recognises the legitimate rights of MNEs’ subsidiaries as well as their stakeholders.

If SLOs are to become a useful pillar of extraterritorial responsibility, the scope of the community will be essential in their establishment and implementation. In most communities in which MNEs operate, various stakeholders will stake a claim in deciding what is acceptable to the community. Therefore, attaining a certain level of consent in SLO schemes should begin with identifying the nature and scope of the groups who are the licensors of the SLO and their expectations.

6.3. SLOs Will Promote Board Accountability

The notion of the SLO was initially advanced as a response to an initiative from the United Nations that requires corporations doing business in territories that are home to indigenous people to safeguard “free, prior, and informed consent” from those indigenous communities and stakeholders in order to build an equal and respectful relationship [95]. Companies should respect the legitimate authority of communities and stakeholders “based on the principle of informed consent” [95,96]. An SLO requires corporations to meet sustainable growth expectations by concentrating on the interests of the community members within their business operative region; a couple of key cases involving vulnerable communities’ expectations of MNEs and their subsidiaries are Okpabi v. Royal Dutch Shell PLC AAA and Others versus Unilever PLC and another [88] and Vedanta Resources PLC and Another v. Lungowe [80].

As a notion related to board accountability, achieving an SLO involves five steps [59]. In Step 1, boards need to describe how the company would meet the expectations of the local community in order to obtain an SLO. In Step 2, boards collect information on social contracts with the impacted stakeholder groups. This information may be collected from the government, NGOs or other stakeholders through mutual communication. In Step 3, boards investigate the configuration between their corporate norms and the social contracts of the stakeholders. In Step 4, boards consult the community members to formulate a proposal, which will lead to agreement by the majority of the entrusted stakeholders for an SLO. In Step 5, boards must monitor the development of the proposal to ensure compliance, and that the proposal and projects in it are proceeding as agreed [59]. These steps have a number of common characteristics with board accountability mechanisms, which involve transparency, stakeholder communication and stakeholder scrutiny [97]. Therefore, maintaining an SLO will be an important ongoing activity for promoting more accountable boards, especially to safeguard the interests of communities.

6.4. SLOs Will Guide Risk Management

The SLO is not only a formula of control that entails companies to meet social, environmental and human rights expectations, it also requires them to avoid activities that the stakeholder community find offensive or deem unacceptable, regardless of whether these expectations are enshrined in current legislation [46]. Black suggests that “managing risk and reputation is generally why companies think about how to protect their social licence” [52]. On the one hand, failing to secure an SLO is regarded as a main risk for companies in CSR-sensitive sectors such as natural resource-based industries, which may give rise to protests and litigation [98]. On the other hand, after an SLO has been developed, the risk management of the company will be guided and regulated by it. Thus, an effective SLO will equip directors with knowledge for measuring risks and formulating corporate strategies to inform their assessment of the legitimacy of their corporate decisions [99].

Because the conditions and terms required by an SLO may be stricter than those imposed by regulation, an SLO will help companies to develop sophisticated risk management strategies so decision makers will understand why, when and to what extent they should go beyond compliance with legal obligations and consider the terms imposed by the SLO [46]. Breaches of the terms and conditions of an SLO, as a form of social contract, will spread environmental risk awareness and trigger negative reactions from stakeholder communities, as well as the need for a system of environmental accountability.

7. Conclusions and Limitation of the Research

Kofi Annan, the seventh Secretary-General of the United Nations, reminded us that the fragility of globalisation has been underestimated and any imbalance between the economic, social and political realms cannot be continued [100]. Although the vulnerability of MNEs’ value chains can be addressed through treaty, negotiation and consensus among super powerful MNEs [101], fairness and equality are still undermined by the failure to protect vulnerable parties. With operations that span the globe, MNEs have an imperative role to play in facilitating the risks of globalisation.

In the absence of internationally recognised legal principles in relation to piercing the corporate veil and sound board accountability mechanisms, extraterritorial responsibilities for MNEs have been introduced or proposed in law. These exercises in extraterritoriality are “frequently controversial” and sometimes even cause “tensions between states” [102,103]. In terms of MNEs and regulatory measures on them and their stakeholder relationships, these are still largely understood or interpreted in minimalistic or moral terms, if at all. It is difficult to justify that stakeholders’ socio-economic deprivation is entirely the responsibility of companies from an external state.

A number of theoretical implications may be drawn from these findings. First, we have investigated the relationship between mandatory corporate extraterritorial responsibility and SLOs, and we conclude that an SLO will give companies social legitimacy to undertake shared responsibility for delivering social justice and equality. Second, an SLO will go some way towards promoting more accountable companies, MNEs in particular. Many corporations are adopting SLOs to mitigate social risks and protect both their own interests and those of their stakeholders. We have also noted that SLOs and board accountability are mutually enhancing notions, and boards must be able to interact with and be monitored by stakeholder communities if they wish to generate the consent of the community and thereby develop their companies in a sustainable and stable environment. Third, an SLO may be used as a tool to ensure a company’s commitment to social norms and community values. In order to generate, implement and maintain an SLO, corporations need to build social legitimacy and trustworthiness with communities and wider stakeholders. The notion of the SLO is also consistent with business cases for CSR and directors’ duties to promote the long-term interests of the company.

The following practical implications for legal practitioners, board members and policymakers could be suggested. Due to the sensitive nature of CSR in most of the industries that currently pay attention to SLOs, when addressing SLOs and corporate responsibilities the focus of research has always been on the SLOs of these particular industries. We suggest that when the notion of the SLO is applied universally across all industries, other equally important aspects are highlighted, such as the classification, nature and scope of the community, and particularly business relationships between MNEs as parent companies, their subsidiaries, and communities in developing and the least developed countries. This shift in focus will provide a useful channel for inspiring an effective and popular use of the notion by corporations and legislators.

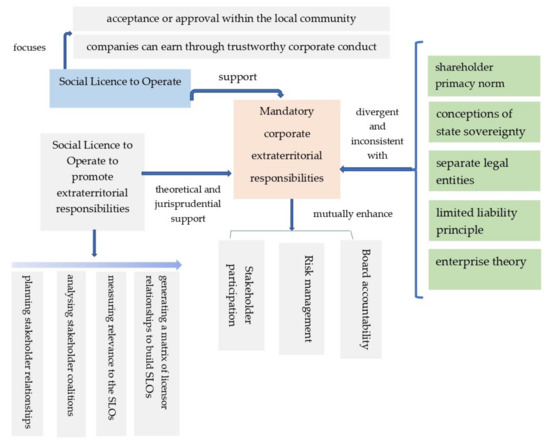

This research should also provide an essential primer for legal practitioners, particularly in-house counsel who have to deal with CSR issues regularly and offer guidance to obtain and maintain SLOs. Board members should follow the steps to ascertain the nature and scope of different licensors in the process of maintaining SLOs, including planning stakeholder relationships, analysing stakeholder coalitions, measuring the nature of stakeholders’ authority and relevance to the SLOs, and generating a matrix of licensor relationships to build sustainable SLOs. The interconnections between notions and arguments are represented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

The interconnections between SLOs and mandatory extraterritorial responsibility and guidance for practitioners to improve their corporate extraterritorial responsibility through SLOs.

A limitation of this article is that it is unable to fully investigate the links between different company approaches and SLOs. For example, there are gaps in the current literature in terms of the linkages between SLOs and specific company law regulatory approaches such as directors’ duties, mandatory transparency or philanthropic responsibilities in the context of extraterritorial responsibilities within individual jurisdictions. Moreover, although the concept of the SLO originated in the mining industry [104,105], it is also valuable to deliberate the application of the concept in other CSR-sensitive industries such as oil and gas, energy, tourism and other large infrastructure industries. Important topics for further research include the application of SLOs in different industries, and the enforcement of extraterritorial responsibility to promote the interests of particular stakeholder groups such as employees.

Author Contributions

J.Z., X.L. and W.L. conceived, designed and wrote this Article together. All authors contribute equally to this article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the NTU Global Challenge Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kinley, D.; Tadaki, J. From Talk to Walk: The Emergence of Human Rights Responsibilities for Corporations at International Law. Va. J. Int. L. 2004, 44, 931–960. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein, K. Australian Citizenship Law in Context; Law Book Co of Australasia: Sydney, Australia, 2002; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Ascensio, H. Contribution to the Work of the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative on Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and other Businesses: Extraterritoriality as an Instrument. 2022. Available online: https://media.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/31691c168cfe77e298345cf255b337e4748fb57d.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- McCorquodale, R.; Simons, P. Responsibility beyond Borders: State Responsibility for Extraterritorial Violations by Corporations of International Human Rights Law. Mod. L. Rev. 2007, 70, 598–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Section 1 of Companies Act 2006, UK. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/46/contents (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Bollier, D. The Growth of the Commons Paradigm. In Understanding Knowledge as a Commons: From Theory to Practice; Hess, C., Ostrom, E., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office UK. UK International Priorities: A Strategy for the FCO; Foreign and Commonwealth Office UK: London, UK, 2003; p. 38.

- Morrison v. Australia National Bank, Ltd. 561, U.S., 130 S. Ct. 2869 (2010). Available online: https://www.lexisnexis.com/community/casebrief/p/casebrief-morrison-v-national-australia-bank-ltd (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., 569 U.S., 133 S. Ct. 1659 (2013). Available online: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/12pdf/10-1491_l6gn.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Stephan, P.B. The Political Economy of Extraterritoriality. Politics Gov. 2013, 1, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, P. Vulnerability and Globalisation: Mediating Impacts on Society. J. Hum. Rights Environ. 2011, 2, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrana-Tévar, N. The International Responsibility of the Holy See for Human Rights Violations. Religions 2022, 13, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, L.; De Albuquerque, C.; Roaf, V.; Jiménez, A. Overview of 12 Years of Special Rapporteurs on the Human Rights to Water and Sanitation: Looking Forward to Future Challenges. Water 2020, 12, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogoviz, A.V.; Lobova, S.V.; Alekseev, A.N. The Concept of Corporate Social Responsibility Based on Integrating the SDGs into Corporate Strategies: International Experience and the Risks for Profit. Risks 2022, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Bi, M.; Jia, D. Corporate Social Responsibility Risk and Firm Performance: A Network Perspective. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2022, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowska-Woszczycka, A.; Pactwa, K. Social License for Closure—A Participatory Approach to the Management of the Mine Closure Process. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, M.-J.; Durán, J.-J.; Avilés-Palacios, C. Managing Reputation in MNEs through Intangible Liabilities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, A.L.; Nogueira, F.; Gonçalves, S.P.; Marques, I.C.P. Work-Family Interface in the Context of Social Responsibility: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, N. The Impact of CSR on the Performance of a Dual-Channel Closed-Loop Supply Chain under Two Carbon Regulatory Policies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A.; Sands, J.; Rahman, H.U. Environmental, Social and Governance Disclosure and Value Generation: Is the Financial Industry Different? Sustainability 2022, 14, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, D.; Rodriguez, A.C.; de Castro Casa Nova, S.P.; Ardichvili, A.A. Five Practices for Building Local Capacity in Sustainability-Driven Entrepreneurship for Place-Based Transformations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagts, D. The Multinational Enterprise: A New Challenge for Transnational Law. Harv. L. Rev. 1970, 83, 738–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatouros, A.A. The Computer and the Mud Hut: Notes on Multinational Enterprise in Developing Countries. Colum. J. Transnat’l L. 1971, 10, 325–326. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, M.; Tiwari, T.; Santhose, S.S.; Mishra, L.; Rejeesh, M.R.; Sundararaj, V. Corporate social responsibility and supply chain: A study for evaluating corporate hypocrisy with special focus on stakeholders. Int. J. Fin. Econ. 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economist. The Retreat of the Global Company. 2017. Available online: https://www.economist.com/briefing/2017/01/28/the-retreat-of-the-global-company (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Salmon, J. Dictionary of Public International Law; Bruylant/University Agency of the Francophonie: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; p. 491. [Google Scholar]

- Senz, D.; Charlesworth, H. Building Blocks: Australia’s Response to Foreign Extraterritorial Legislation. Melb. J. Int. Law 2001, 2, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Schutter, O. Sovereignty-Plus in the Era of Interdependence: Towards an International Convention on Combating Human Right Violations by Transnational Corporations. In Making Transnational Law Work in the Global Economy: Essays in Honour of Detlev Vagts; Bekker, P.H.F., Doler, R., Waibel, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 245+274–275. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, M.; Janda, R.; Pitts, C. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Legal Analysis; LexisNexis: Markham, ON, Canada, 2009; pp. 472–475+595. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland-Piper, D. Extraterritorial Criminal Jurisdiction: Does the Long Arm of the Law Undermine the Rule of Law. Melb. J. Int. Law 2012, 13, 122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zerk, J.A. Multinationals and Corporate Social Responsibility: Limitation and Opportunity in Internationals Law; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cossart, S.; Chaplier, J.; Lomenie, T. The French Law on Duty of Care: A Historic Step Towards Making Globalization Work for All. Bus. Hum. Rights J. 2017, 2, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dine, J. Stopping Jurisdictional Arbitrage by Multinational Companies: A National Solution. Eur. Co. L. 2014, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Article 209 (1)3 Company Act of Albania. 2008. Available online: http://images.mofcom.gov.cn/al/201401/2014010617380694.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Article 210 Company Act of Albania. 2008. Available online: http://images.mofcom.gov.cn/al/201401/2014010617380694.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Article 211 Company Act of Albania. 2008. Available online: http://images.mofcom.gov.cn/al/201401/2014010617380694.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Chandler v Cape Plc, E.W.C.A. Civ 525 (2012). Available online: https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/doc-chandler-v-cape-plc-judgment/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Sanger, A. Crossing the Corporate Veil: The Duty of Care Owed by a Parent Company to The Employees of its Subsidiary. Cam. Law J. 2012, 71, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, G.C. The Theory of Enterprise Liability and Common Law Strict Liability. Vand. Law Rev. 2001, 54, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoco Cadiz Oil Spill, 1984 A.M.C. 2123, 2 Lloyd’s Rep 304 (N.D. Ill. 1984). Available online: https://casetext.com/case/matter-of-oil-spill-by-the-amoco-cadiz (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s. 5. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018C00031 (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s. 186. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018C00031 (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Zhao, J. Extraterritorial Attempts at Addressing Challenges to Corporate Sustainability. In Cambridge Handbook of Corporate Law, Corporate Governance and Sustainability; Sjåfjell, B., Brunner, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kendal, D.M. CSR and Extraterritorial Jurisdiction—International Law Boundaries to Human Rights Litigation; Kendal Human Right Consulting Issues Paper; Kendal Human Right Consulting: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Investopedia. Social License to Operate. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/social-license-slo.asp (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Gunningham, N.; Kagan, R.; Thornton, D. Social License and Environmental Protection: Why Businesses Go Beyond Compliance. Law Soc. Inq. 2004, 29, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pro Bono Australia. The Very Seductive Social License to Operate—A Reality Check. 2012. Available online: https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2012/10/the-very-seductive-social-license-to-operate-a-reality-check/ (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- Thomson, I.; Boutilier, R.G. Social Licence to Operate. In SME Mining Engineering Handbook, Society for Mining, Metallurgy and Exploration; Darling, P., Ed.; SME Books: Englewood, CO, USA, 2011; pp. 1779–1796. [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen, J.L. Social Licence to Operate: Industry Survey; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D. Social Licence and Mining: A Critical Perspective. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelsen, J.L. Social License to Operate. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2006, 20, 161–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L. The Social License to Operate: Your Management Framework for Complex Times; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Asmus, P. When It Comes to Water, Can Corporations and Community Really Coexist? 2009, p. 8. Available online: http://peaceandjustice.org/article.php/20090820081745528 (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Wilburn, K.M.; Wilburn, H.R. Demonstrating a Commitment to Corporate Social Responsibility Not Simply Shared Value. Bus. Prof. Ethics J. 2014, 33, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, W.H. The Social License to Operate; PIMA Magazine, Paper Industry Management Association: Norcross, GA, USA, 1996; pp. 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Boutilier, R.G.; Thomson, I. The Social License: The Story of the San Cristobal Mine; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- International Council on Mining and Metals. Mining’s Contribution to Sustainable Development: An Overview; International Council on Mining and Metals: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, S. Global production, CSR and human rights: The courts of public opinion and the social licence to operate. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2015, 19, 757–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilburn, K.M.; Wilburn, R. Achieving Social License to Operate Using Stakeholder Theory. J. Int. Bus. Ethics 2011, 4, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Demuijnck, G.; Fasterling, B. The Social License to Operate. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, N.; Lacey, J.; Carr-Cornish, S.; Dowd, A. Social Licence to Operate: Understanding How a Concept has been Translated into Practice in Energy Industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J. The Social License How to Keep Your Organization Legitimate; Palgrave: London, UK, 2014; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel, T. Court of Law and Court of Public Opinion: Symbiotic Regulation of the Corporate Management Duty of Care. N. Y. Univ. J. Law Bus. 2007, 3, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Boutilier, R.G. Frequently Asked Questions About the Social Licence to Operate. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2014, 32, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WattPoultry, Interview for Charlie Arnot, Terence O’Keefe. Social License Provides Freedom to Operate. 2009. Available online: https://www.wattagnet.com/articles/315-social-license-provides-freedom-to-operate (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- Padfield, S.J. Corporate Social Responsibility and Concession Theory. William Mary L. Rev. 2015, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dare, M.; Schirmer, J.; Vanclay, F. Community engagement and social licence to operate. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais 2014, 32, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxfam America. Community Consent Index: Oil, Gas and Mining Company Public Positions on Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC); Oxfam America: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Consumers Health Forum of Australia. Ethical Issues Arising from the COVID-19 Pandemic Consumer Position Statement; Consumers Health Forum of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, R.; Moffat, K. Constructing the Meaning of Social Licence. Soc. Epistemol. 2014, 28, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian, Business and Society: Defining The ‘Social Licence’. 2014. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2014/sep/29/social-licence-operate-shell-bp-business-leaders (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- Lacey, J.; Parsons, R.; Moffat, K. Exploring the Concept of a Social Licence to Operate in The Australian Minerals Industry Results from Interviews with Industry Representatives; EP125553; CSIRO: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2012.

- Joyce, S.; Thomson, I. Earning A Social Licence to Operate: Social Acceptability and Resource Development in Latin America. Can. Min. Metall. B. 2000, 93, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Post, J.E.; Preston, L.E.; Sachs, S. Redefining the Corporation: Stakeholder Management and Organizational Wealth; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2002; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, I.; Joyce, S. The social licence to operate: What it is and why it seems so hard to obtain. In Proceedings of the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada Annual Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, C. Corporate Liability for Toxic Torts Abroad: Vedanta v. Lungowe in the Supreme Court. J. Environ. Law 2020, 32, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croser, M.; Day, M.; Van Huijstee, M.; Samkalden, C. Vedanta v. Lungowe and Kiobel v Shell: The Implications for Parent Company Accountability. Bus. Hum. Rights J. 2020, 5, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varvastian, S.; Kalunga, F. Transnational Corporate Liability for Environmental Damage and Climate Change: Reassessing Access to Justice after Vedanta v. Lungowe. Trans. Environ. Law 2020, 9, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, E. Transnational Corporate Liability Litigation and Access to Environmental Justice: The Vedanta v. Lungowe Case. L.S.E. Law Rev. 2021, 6, 223–248. [Google Scholar]

- Vedanta Resources Plc and Another v. Lungowe [2019] UKSC 20; UK Supreme Court: London, UK, 2019. Available online: https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2017-0185.html (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Van Ho, T. Vedanta Resources Plc and Another v. Lungowe and Others [2019] UKSC 20″. Am. J. Int’l L. 2020, 114, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbe v Cape plc [2000] 1 WLR 1545. Available online: https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/Link/Document/FullText?findType=Y&serNum=0465940008&pubNum=231975&originating-Doc=IFB77B4500B9C11E8BB889F8161330197&refType=UB&originationContext=document&transitionType=DocumentItem&ppcid=ebcba0b508684b7f8d161aff8e51defd&contextData=(sc.Category)&firstPage=true#co_pp_sp_231975_3e50d63e-596a-46b1-bb4b-e5125f2c091b (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Thompson v The Renwick Group plc [2014] EWCA Civ 635. Available online: https://www.blmlaw.com/news/thompson-v-the-renwick-group-plc-2014-ewca-civ-635#:~:text=Summary%3A%20in%20an%20asbestos%2Drelated,employee%20of%20its%20subsidiary%20company (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Bueno, N.; Bright, C. Implementing human rights due diligence through corporate civil liability. Int. Comp. Law Q. 2020, 69, 789–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esther Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Shell PLC [2019] ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2019:4233. Available online: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/12pdf/10-1491_l6gn.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Hopkins, R. Nevsun Resources Ltd. v. Araya. SCC 5 (workers’ forced labour in a mine in Eritrea). Int. Leg. Mater. 2020, 59, 747–810. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, S. Vedanta resources plc and another lungowe and others. North. Irel. Leg. Q. 2019, 70, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpabi v. Royal Dutch Shell Plc & Another [2021] UKSC 3. Available online: https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2018-0068.html (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Ye, B. Okpabi v. Shell and Nestle USA v. Doe: Trend and Divergence on Parent Company Liability for Human Rights Abuse in the United Kingdom and United States. N.Y.U. J. Int. Law Politics 2021, 54, 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney, J. Extraterritorial corporate liability for environmental harm: Okpabi v Royal Dutch Shell. North. Irel. Leg. Q. 2019, 70, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch-Wood, G.; Williamson, D. The Social Licence as a Form of Regulation for Small and Medium Enterprises. J. Law Soc. 2007, 34, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) s. 1324. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018C00031 (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Cermak, R. Directors’ Duties to Respect Human Rights in Offshore Operations and Supply Chains: An Emerging Paradigm. Co. Secur. Law J. 2018, 36, 124–148. [Google Scholar]

- International Chamber of Commerce, Policy Statement: Extraterritoriality and Business. 2006, p. 5. Available online: https://cdn.iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2006/07/Extraterritoriality-and-business.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Para 35, 64–65 United Nations, Commission on Human Rights, Sub-Commission on The Promotion and Protection of Human Rights; Working Group on Indigenous Populations, Twenty-Second Session; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2004.

- Wen, S.; Zhao, J. The Commons, the Common Good and Extraterritoriality: Seeking Sustainable Global Justice through Corporate Responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Regulation of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Lens of Board Accountability and the Case of China. In Globalisation of Corporate Social Responsibility and its Impacts on Corporate Governance; Plessis, J., Veldman, J., Varottil, U., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 121–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna, P.; Vanclay, F.; Langdon, E.J.; Arts, J. Conceptualizing Social Protest and The Significance of Protest Action to Large Projects. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2016, 3, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meesters, M.; Wostyn, P.; Leeuwen, J.; Behagel, J.H.; Turnhout, E. The Social Licence to Operate and the legitimacy of resource extraction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 49, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, K.A. A Compact for the New Century; World Economic Forum: Davos, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Buck, S.J. The Global Commons: An Introduction; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Zerk, J.A. Extraterritorial Jurisdiction: Lessons for the Business and The Work of Nations: Preparing Ourselves for 21 Century Capitalism; Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Available online: https://www.hks.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/centers/mrcbg/programs/cri/files/workingpaper_59_zerk.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Zerk, J.A. Extraterritorial Jurisdiction: Lessons for the Business and Human Rights Sphere from Six Regulatory Areas; Working Paper No 59; Harvard Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Kot-Niewiadomska, A. The Role of Mineral Raw Materials Education in a Social License to Operate—A Case of Poland. Resources 2022, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuah-Offei, K.; Que, S.; Ur Rehman, A. Evaluating Mine Design Alternatives for Social Risks Using Discrete Choice Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).