Effect of Ethical Climate in Hotel Companies on Organizational Trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ethical Climate

2.2. Organizational Trust

2.3. Organizational Citizenship Behavior

3. Methodology

3.1. Development of Measures

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis Method

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Correlation Analysis

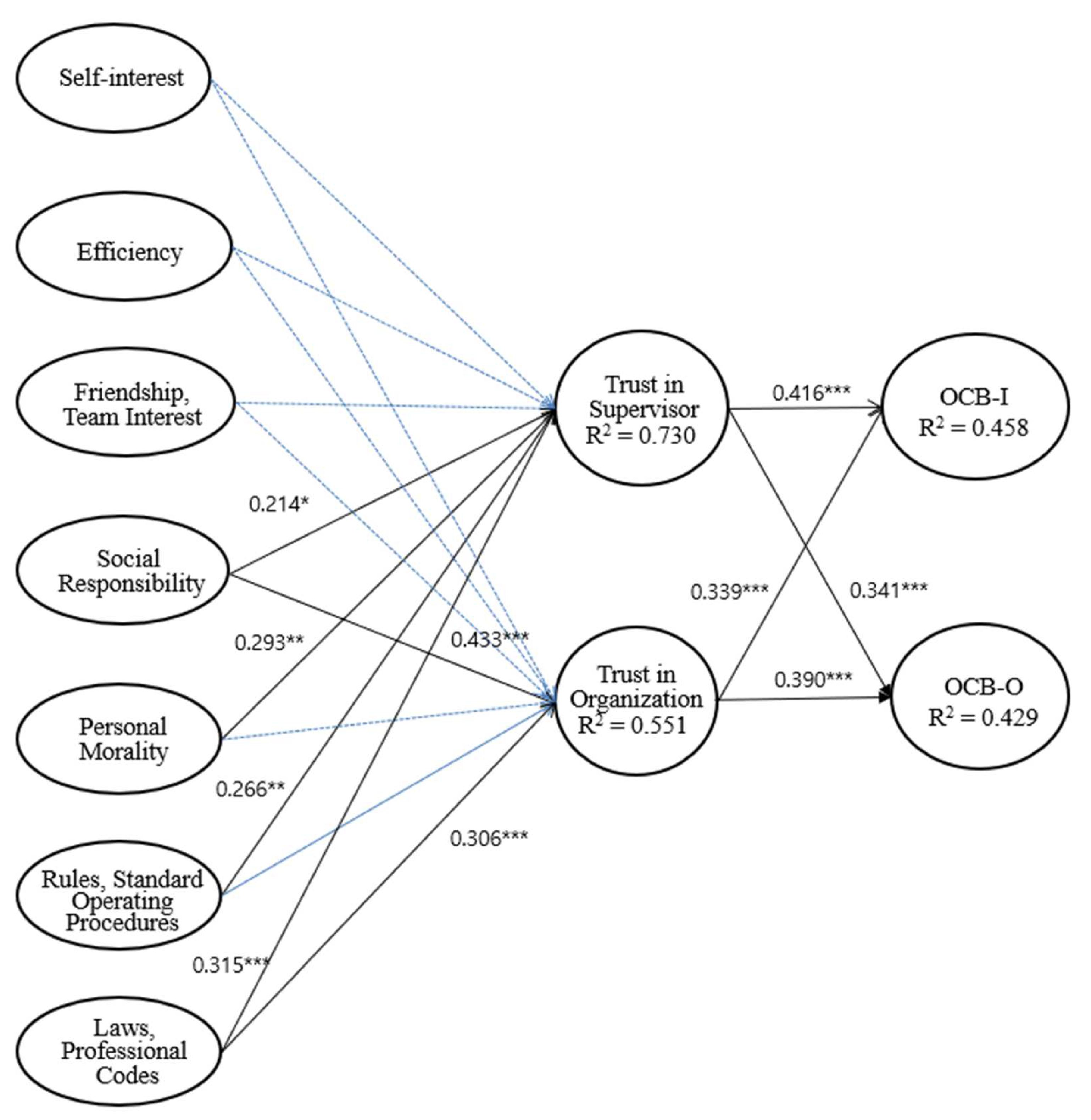

4.4. Structural Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Implications

5.2. Limitations and Further Research Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferrell, O.C.; Fraedrich, J.; Ferrell, L. Business Ethics: Ethical Decision Making and Cases, 8th ed.; South-Western Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kidder, R.M. How Good People Make Tough Choices: Resolving the Dilemmas of Ethical Living; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, M.; Manning, M.; Timo, N.; Ryder, P. The dimensions of organizational climate in four and five-star Australian hotels. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2001, 25, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, V.; Ashforth, B.E.; Joshi, M. Business as usual: The acceptance and perpetuation of corruption in organizations. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2004, 18, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish-Gephart, J.; Harrison, D.A.; Treviño, L.K. Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. A theory and measure of ethical climate in organizations. In Research in Corporate Social Performance; Frederick, W.C., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1987; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, M.W.; Smith, D.B.; Grojean, M. An organizational climate regarding ethic: The outcome of leader values and the practices that reflect them. Leadersh. Q. 2001, 12, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsche, D.J. Ethical climate and the ethical dimension of decision making. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 24, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.S.; Lin, C.C. The effects of ethical leadership and ethical climate on employee ethical behavior in the international port context. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.B.; Parboteeah, K.P.; Victor, B. The effects of ethical climates on organizational commitment: A two-study analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh, M.; Belak, J.; Milfelner, B. Core values, culture and ethical climate as constitutional elements of ethical behaviour: Exploring differences between family and non-family enterprises. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. The Organizational bases of ethical work climates. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 33, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lützén, K.; Kvist, B.E. Moral distress: A comparative analysis of theoretical understandings and inter-related concepts. HEC Forum. 2012, 24, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, D.K. The relationship between unethical behavior and the dimensions of the ethical climate questionnaire. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 41, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.Y.; Wang, L. The mediating effect of ethical climate on the relationship between paternalistic leadership and team identification: A team-level analysis in the Chinese context. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 129, 639–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.H.; Tan, C.S.F. Toward the differentiation of trust in supervisor and trust in organization. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 2000, 126, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, C.; Dixon, R.D. Love, forgiveness, and trust: Critical values of the modern leader. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirks, K.T.; Ferrin, D.L. Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.S.; Sims, D.E.; Lazzara, E.H.; Salas, E. Trust in leadership: A multi-level review and integration. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 606–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.; Finegan, H.K.; Shamian, J. The impact of workplace empowerment, organizational trust on staff nurses’ work satisfaction and organizational commitment. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Turnley, W.H. Going the extra mile: Cultivating and managing employee citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2003, 17, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.K.; Baniya, R. Emotional intelligence and employee outcomes: Moderating role of organizational politics. Bus. Perspect. Res. 2016, 4, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, P.; Bidarian, S. The relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 47, 1815–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Blume, B.D. Individual-and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Aryee, S.; Law, K.S. High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior and organizational. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upchurch, R.S.; Ruhland, S.K. The organizational bases of ethical work climates in lodging operations as perceived by general managers. J. Bus. Ethics 1996, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S.H.; Banks, H.S.C.; Lee, K.H. An ethical work climate and its consequences among food-service franchise employees. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 20, 1286–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menes, C.C.; Haguisan, I.A. III. Ethical climate, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment of hotel employees. Philipp. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 3, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwepker, C.H., Jr.; Hartline, M.D. Managing the ethical climate of customer-contact service employees. J. Serv. Res. 2005, 7, 377–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M. Inking perceived ethical climate to performance outcomes: The mediating role of job embeddedness. Ekon. Istraž. Econ. Res. 2013, 26, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P.; Guerra-Báez, R. Exploring the influence of ethical climate on employee compassion in the hospitality industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I.E.; Elbaz, A.M.; Elkhwesky, Z.; Ghazi, K.M. The COVID-19 pandemic: The mitigating role of government and hotel support of hotel employees in Egypt. Tour. Manag. 2021, 85, 104305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, F.C.; Fan, Y.J. Exploring the influence of organizational ethical climate on knowledge management. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.C.; Lu, A.C.C.; Huang, J.Y.; Fan, C.H. Ethical work climate, organizational identification, leader-member-exchange (LMX) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): A study of three star hotels in Taiwan. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Agbaim, I.M. Perceived ethical climate and hotel employee outcomes: An empirical investigation in Nigeria. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2012, 13, 286–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, K.; Kim, W.G.; Chang, H.S.; Li, J.J. Workplace spirituality as a mediator between ethical climate and workplace deviant behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 86, 102372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.C.K.; Li, J.S. Will hotel employees’ perception of unethical managerial behavior affect their job satisfaction? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 853–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.B.; Victor, B.; Bronson, J.W. The Ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychol. Rep. 1993, 73, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.D.; Cullen, J.B. Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: A meta-analytic review. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simha, A.; Cullen, J.B. Ethical climates and their effects on organizational outcomes: Implications from the past and prophecies for the future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 26, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, S.; Weißenberger, B.E. The relationship between informal controls, ethical work climates, and organizational performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeConinck, J.B. The effects of ethical climate on organizational identification, supervisory trust, and turnover among salespeople. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simha, A.; Stachowicz-Stanusch, A. The effects of ethical climates on trust in supervisor and trust in organization in a Polish context. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilly, J.; Duffy, J.A.; WIpawayangkool, K. The impact of ethical climate on organizational trust and the role of business performance: If business performance increases, does ethical climate still matter? J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2016, 17, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Nedkovski, V.; Guerci, M.; De Battisti, F.; Siletti, E. Organizational ethical climates and employee’s trust in colleagues, the supervisor, and the organization. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 71, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.K. Do ethical climates impact trust in management? A study in Indian context. Int. J. Org. Anal. 2017, 25, 804–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Scott, B.A.; LePine, J.A. Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 909–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.L. Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Adm. Sci. Q. 1996, 41, 574–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.; Sitkin, S.; Burt, R.; Camerer, C. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Wall, T. New work attitude measure of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non-fulfillment. J. Occup. Psychol. 1980, 53, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitener, E.M. The impact of human resource activities on employee trust. Hum. Res. Manag. Rev. 1997, 7, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özlük, B.; Baykal, Ü. Organizational citizenship behavior among nurses: The influence of organizational trust and job satisfaction. Florence Nightingale J. Nurs. 2020, 28, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.T.; Ngo, H.Y.; Wong, C.S. Perceived organizational justice, trust, and OCB: A study of Chinese workers in joint ventures and state-owned enterprises. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, N.; Qiu, S.; Yang, S.; Deng, R. Ethical leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: Mediation of trust and psychological well-being. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.; Jang, J.; Lee, J. Environmental management strategy and organizational citizenship behaviors in the hotel industry: The mediating role of organizational trust and commitment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1577–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choong, Y.O.; Ng, L.P. The effects of trust on efficacy among teachers: The role of organizational citizenship behaviour as a mediator. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Kemal, I. The effect of trust and job satisfaction on citizenship organizational behavior in high school. AL-ISHLAH J. Pendidik. 2021, 13, 1348–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, A.; Hendrikz, K. Influence of moral intelligence, principled leadership and trust on organizational citizenship behaviour. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2020, 23, a3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, R.C.; Marlowe, H.A., Jr. Development and psychometric properties of the organizational trust inventory. Eval. Rev. 1997, 21, 614–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Syed, S.I. Frontline employees’ high-performance work practices, trust in supervisor, job-embeddedness and turnover intentions in hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1436–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Park, S. The role of transformational leadership in citizenship behavior. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 1347–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Humphrey, R.H.; Qian, S. A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence effects on job satisfaction mediated by job resources, and a test of moderator. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. The motivational basis of organizational citizenship behavior. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Staw, B.M., Cummings, L.L., Eds.; Jai Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1990; pp. 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C.A.; Organ, D.W.; Near, J.P. Organizational citizenship behavior: Its nature and antecedents. J. Appl. Psychol. 1983, 68, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.; Qu, H.; Wilson, M.; Eastman, K. Modeling OCB for hotels don’t forget the customers. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2013, 54, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, A. Increasing organizational citizenship behaviors of Turkish academicians mediating role of trust in supervisor on the relationship between organizational justice and citizenship behaviors. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 22, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ötken. A.V.; Cenkci, T. The impact of paternalistic leadership on ethical climate: The moderating role of trust in leader. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Moorman, R.H.; Fetter, R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadersh. Q. 1990, 1, 107–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. 2020 Annual Report on Tourism Trends. Available online: https://www.mcst.go.kr/kor/s_policy/dept/deptView.jsp?pSeq=1846&pDataCD=0406000000&pType= (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Chen, C.H.; Wang, S.J.; Chang, W.C.; Hu, C.S. The effect of leader-member exchange, trust, supervisor support on organizational citizenship behavior in nurses. J. Nurs. Res. 2008, 16, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Preston, L.E.; Sachs, S. Redefining the Corporation: Stakeholder Management and Organizational Wealth; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Selznick, P. The Moral Commonwealth: Social Theory and the Promise of Community; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA; Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Frequency (Person) | Percentage (%) | Variable | Frequency (Person) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Position | ||||

| Male Female | 211 131 | 61.7 38.3 | Entry level Supervisory level Managerial level or Executive level | 235 86 21 | 68.7 25.1 6.1 |

| Age | Working department | ||||

| 20–29 30–39 40–49 ≥50 | 97 138 83 24 | 28.4 40.4 24.3 7.0 | Rooms Food and beverage Culinary Marketing/operational support Facilities | 76 138 48 69 11 | 22.2 40.4 14.0 20.2 3.2 |

| Education level | Years of experience in hotel industry | ||||

| High school or less Two- or three-year college Four-year university Master’s degree and above | 22 114 161 45 | 6.4 33.3 47.1 13.2 | ≤4 years 5–9 years 10–14 years 15–19 years ≥20 years | 115 114 56 37 20 | 33.6 33.3 16.4 10.8 5.8 |

| Construct and Scale Item | Standardized Factor Loadings | CR (t-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-interest (AVE = 0.611, CCR = 0.825, Cronbach’s α = 0.810) | ||

| We hotel employees are interested in protecting our interests. We hotel employees consider our own interests first in decision making. We hotel employees strive for our personal interests. | 0.766 0.780 0.762 | 12.631 12.490 |

| Efficiency (AVE = 0.643, CCR = 0.843, Cronbach’s α = 0.760) | ||

| Performing tasks efficiently at our hotel is an important duty of employees. Performing tasks most efficiently is the best way to work at our hotel. Our hotel considers work efficiency important. | 0.639 0.717 0.791 | 10.359 10.939 |

| Friendship, team interest (AVE = 0.649, CCR = 0.880, Cronbach’s α = 0.834) | ||

| The main concern of our hotel is what is best for employees. Our hotel considers the situations (dispositions) of individual employees in decision making. Our hotel considers the common interests of employees important. Our hotel strives to make the best choice for all employees. Our hotel values the happiness of all employees. | 0.642 0.759 0.708 0.801 0.653 | 11.533 10.927 11.983 10.254 |

| Social responsibility (AVE = 0.717, CCR = 0.835, Cronbach’s α = 0.739) | ||

| We hotel employees consider customers and public interests important when performing tasks. Our hotel makes decisions considering the impact on customers and public interests. | 0.771 0.761 | 12.107 |

| Personal morality (AVE = 0.706, CCR = 0.905, Cronbach’s α = 0.860) | ||

| Employees at our hotel tend to follow their moral beliefs when performing tasks. Employees judge what is “right or wrong” themselves when performing tasks. Our hotel values and respects the personal judgment of employees about what is “right or wrong.” Employees act according to their moral beliefs. | 0.784 0.712 0.840 0.776 | 13.450 16.236 14.865 |

| Rules, standard operating procedures (AVE = 0.668, CCR = 0.889, Cronbach’s α = 0.840) | ||

| Strictly complying with rules and procedures is extremely important at our hotel. Our hotel requires all employees to comply with rules and procedures. Employees complying with rules and procedures succeed at our hotel. Employees complying with hotel policies succeed. | 0.772 0.726 0.805 0.712 | 13.332 14.900 13.060 |

| Laws, professional codes (AVE = 0.669, CCR = 0.858, Cronbach’s α = 0.769) | ||

| Following laws or professional ethical codes is an important matter in our hotel. Laws and professional codes must be observed first when performing tasks at our hotel. Our hotel requires employees to comply strictly with legal standards or professional codes. | 0.705 0.755 0.719 | 11.494 11.119 |

| Trust in supervisor (AVE = 0.612, CCR = 0.863, Cronbach’s α = 0.781) | ||

| I trust the words and actions of my supervisor. My supervisor truly cares about what is important to me. I will support my supervisor even in difficulties. My supervisor provides considerable help in my working life. | 0.669 0.703 0.651 0.722 | 11.015 10.341 11.259 |

| Trust in organization (AVE = 0.658, CCR = 0.885, Cronbach’s α = 0.801) | ||

| Our hotel strives to meet the expectations and interests of employees. I think our hotel’s promises or policies are worth believing and following. I believe that our hotel management will make wise decisions for the company’s future. I trust our hotel. | 0.669 0.696 0.783 0.691 | 10.796 11.770 10.735 |

| OCB-I (AVE = 0.616, CCR = 0.865, Cronbach’s α = 0.808) | ||

| I help my supervisor without request. I help new employees adjust well to the company. I help my colleagues when they have too much work to do. I find the time to listen to my colleagues’ troubles or concerns. I help my colleagues absent from work due to certain reasons. | 0.669 0.675 0.713 0.665 0.663 | 10.573 11.051 10.448 10.417 |

| OCB-O (AVE = 0.623, CCR = 0.868, Cronbach’s α = 0.802) | ||

| I do not waste time unnecessarily when performing tasks. I save and protect the company’s assets. I well observe unofficial rules established to maintain the invisible order. I actively participate in unofficial events of the company, such as workshops and outings. | 0.649 0.770 0.783 0.666 | 11.489 11.619 10.291 |

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 1250.066 (df = 724, p < 0.00), χ2/df = 1.727, RMR = 0.032, SRMR = 0.049, TLI = 0.908, CFI = 0.919, RMSEA = 0.046 | ||

| Construct | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Self-interest | [0.611] | ||||||||||

| (2) Efficiency | 0.429 (0.184) | [0.643] | |||||||||

| (3) Friendship, team interest | 0.434 (0.188) | 0.725 (0.526) | [0.649] | ||||||||

| (4) Social responsibility | 0.339 (0.115) | 0.585 (0.342) | 0.741 (0.549) | [0.717] | |||||||

| (5) Personal morality | 0.315 (0.099) | 0.459 (0.211) | 0.574 (0.329) | 0.579 (0.335) | [0.706] | ||||||

| (6) Rules, standard operating procedures | 0.356 (0.127) | 0.430 (0.185) | 0.546 (0.298) | 0.556 (0.309) | 0.772 (0.596) | [0.668] | |||||

| (7) Laws, professional codes | 0.378 (0.143) | 0.576 (0.332) | 0.572 (0.327) | 0.542 (0.294) | 0.462 (0.213) | 0.529 (0.280) | [0.669] | ||||

| (8) Trust in supervisor | 0.292 (0.085) | 0.461 (0.213) | 0.577 (0.333) | 0.628 (0.394) | 0.719 (0.517) | 0.742 (0.551) | 0.640 (0.410) | [0.612] | |||

| (9) Trust in organization | 0.238 (0.0570 | 0.460 (0.212) | 0.536 (0.287) | 0.647 (0.419) | 0.517 (0.267) | 0.548 (0.300) | 0.566 (0.320) | 0.685 (0.469) | [0.658] | ||

| (10) OCB-I | 0.325 (0.106) | 0.373 (0.139) | 0.366 (0.134) | 0.426 (0.181) | 0.477 (0.228) | 0.437 (0.191) | 0.541 (0.293) | 0.600 (0.360) | 0.570 (0.325) | [0.616] | |

| (11) OCB-O | 0.365 (0.133) | 0.590 (0.348) | 0.471 (0.222) | 0.499 (0.249) | 0.459 (0.211) | 0.450 (0.203) | 0.555 (0.308) | 0.523 (0.274) | 0.553 (0.306) | 0.742 (0.551) | [0.623] |

| Mean | 3.201 | 3.537 | 3.532 | 3.589 | 3.497 | 3.482 | 3.622 | 3.579 | 3.684 | 3.683 | 3.660 |

| S.D | 0.852 | 0.761 | 0.816 | 0.808 | 0.816 | 1.414 | 0.867 | 0.789 | 0.770 | 0.756 | 0.873 |

| Path | Std. Estimate | t-Value | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-interest→Trust in supervisor | −0.027 | −0.478 | Not supported |

| Efficiency→Trust in supervisor | −0.017 | −0.195 | Not supported |

| Friendship, team interest→Trust in supervisor | −0.071 | −0.656 | Not supported |

| Social responsibility→Trust in supervisor | 0.214 | 2.186 * | Supported |

| Personal morality→Trust in supervisor | 0.293 | 3.135 ** | Supported |

| Rules, standard operating procedures→Trust in supervisor | 0.266 | 2.773 ** | Supported |

| Laws, professional codes→Trust in supervisor | 0.351 | 4.378 *** | Supported |

| Self-interest→Trust in organization | −0.051 | −0.801 | Not supported |

| Efficiency→Trust in organization | 0.062 | 0.615 | Not supported |

| Friendship, team interest→Trust in organization | −0.099 | −0.799 | Not supported |

| Social responsibility→Trust in organization | 0.433 | 3.638 *** | Supported |

| Personal morality→Trust in organization | 0.075 | 0.732 | Not supported |

| Rules, standard operating procedures→Trust in organization | 0.136 | 1.283 | Not supported |

| Laws, professional codes→Trust in organization | 0.306 | 3.510 *** | Supported |

| Trust in supervisor→OCB-I | 0.416 | 4.893 *** | Supported |

| Trust in organization→OCB-I | 0.339 | 4.098 *** | Supported |

| Trust in supervisor→OCB-O | 0.341 | 4.109 *** | Supported |

| Trust in organization→OCB-O | 0.390 | 4.574 *** | Supported |

| Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 1370.130 (df = 740), p = 0.000, χ2/df = 1.852, RMR = 0.038,SRMR = 0.059, TLI = 0.892, CFI = 0.903, RMSEA = 0.050 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, S.-Y. Effect of Ethical Climate in Hotel Companies on Organizational Trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7886. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137886

Oh S-Y. Effect of Ethical Climate in Hotel Companies on Organizational Trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7886. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137886

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Seok-Youn. 2022. "Effect of Ethical Climate in Hotel Companies on Organizational Trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7886. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137886

APA StyleOh, S.-Y. (2022). Effect of Ethical Climate in Hotel Companies on Organizational Trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. Sustainability, 14(13), 7886. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137886