Sustainable Development of Underutilized Pedestrian Underpass in Seoul

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Pedestrian Underpasses in Seoul

1.2. Background and Purpose

1.3. Research on Previous Studies and Differentiation

2. Methods

2.1. Sustainability Framework

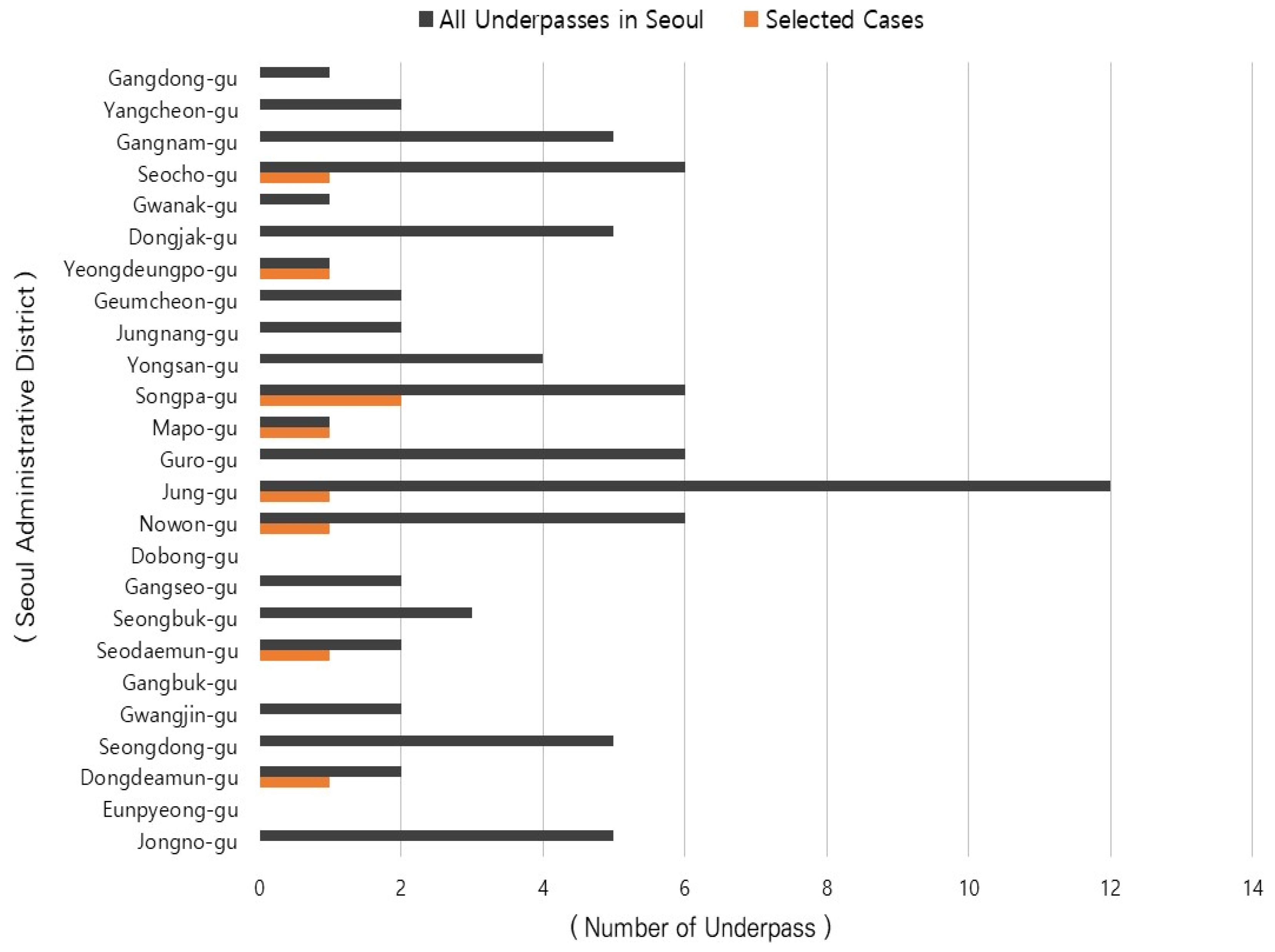

2.2. Case Selection

3. Case Studies

3.1. Comma

3.2. Underland

3.3. The Meet Up Center

3.4. The Village Art Factory

3.5. The Hwigyeong Atelier

3.6. The Musical Instrument Library

3.7. The Seoul Indie Platform

3.8. The Seoripul Gallery

3.9. The Chungmu Startup Cube

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jo, D.H. Temporary Application Plan of Public Underground Walkway Study of the Resolution Method: Focusing on Seoul’s Idle Public Underground Walkways. Master’s Thesis, University of Seoul, Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.H.R. Bunkers as difficult heritage: Imagining future for underground spaces in Seoul. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.Y. A Study on Factors of Pedestrian Crossing Accident on Characteristics of Crossing Facilities. Master’s Thesis, University of Seoul, Seoul, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.J.; Jung, S.H. Empirical Investigation and Comparative Analysis of Urban Public Underground Space—Focused on the Underground Public Pedestrian Facilities in Busan Metropolitan City. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2011, 27, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Allan, A.; Taylor, M.; Lin, D. Developing shanghai underground pedestrian system under urbanization: Mobility, functionality and equity. J. Archit. Urban. 2012, 36, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Nam, J.; Han, J.H. Paradigms of Korean urban policies at each urban growth stage. Korean Hous. Assoc. J. Autumn Acad. Press Conf. 2015, 26, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- The Seoul Research Data Service. Population Change and Population Growth Rate. Available online: https://data.si.re.kr/data/%ED%86%B5%EA%B3%84%EB%A1%9C-%EB%B3%B8-%EC%84%9C%EC%9A%B8-%EC%9D%B8%EA%B5%AC%ED%8E%B8/267 (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- Jeong, B.S. Seoul Metropolitan Theory (New Policy Discourses About the Seoul Metropolis); The Seoul Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gelezeau, V. Séoul, Ville Géante, Cités Radieuses, 10th ed.; Humanitasbook: Seoul, Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, G.J. The negative perceptions of apartment culture as represented in Korean films during the 1970s–1990s. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.S.; Oh, J.S.; Kim, S.Y. The transition from traditional infrastructure to living SOC and its effectiveness for community sustainability: The case of South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.B. The background and challenges of the Seoul community support project: On the occasion of the establishment of the Seoul Community Support Center. Environ. Philos. 2013, 15, 173–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Allan, A.; Taylor, M.; Lin, D. The perception of accessibility and ease of orientation of underground pedestrian systems: A survey in Shanghai. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2012, 16, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, M. Architecture of underground spaces: From isolated innovations to connected urbanism. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishii, T. Utilization of underground space in Japan. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anciaes, P.; Jones, P. Estimating preferences for different types of pedestrian crossing facilities. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018, 52, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, U.; Tiwari, G.; Chatterjee, N.; Fazio, J. Study of Pedestrian Risk Behavior and Survival Analysis. Proc. East. Asia Soc. Transp. Stud. 2009, 7, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankavat, S.; Tiwari, G. Pedestrians perceptions for utilization of pedestrian facilities—Delhi, India. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2016, 42, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, M.K.; Park, S.H. A Study on the Street Environmental Characteristics Influencing Jaywalking Traffic Accidents. J. Korean Reg. Dev. Assoc. 2018, 30, 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Lin, D. Utilisation of underground pedestrian systems for urban sustainability. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmastro, C.; Lavagno, E.; Schranz, L. Underground urbanism: Master Plans and Sectorial Plans. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2016, 55, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. From Pedestrian Thoroughfare to Public Space: The Social Life of the Esplanade Underpass. J. Undergrad. Ethnogr. 2019, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S. A Study on The Culture Network Platform Design of The Cumulative City: Focus on The Space of Sidewalk in The Basement. Master’s Thesis, Hongik University, Seoul, Korea, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.N. The Study on The Development of Design Checklist for The Underground Space Remodeling. Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, R.; Admiraal, H.; Bobylev, N.; Parker, H.; Godard, J.; Vähäaho, I.; Rogers, C.; Shi, X.; Hanamura, T. Sustainability issues for underground space in urban areas. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2012, 165, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland Report. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development—Our Common Future; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Passet, R. L’Économique et le Vivant; Payot: Paris, France, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Enter the triple bottom line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up; Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 23–38. Available online: https://www.johnelkington.com/archive/TBL-elkington-chapter.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Seoul NPO Center. NPO Sustainability Reporting Guidelines: 2016. Available online: http://www.snpo.kr/data//file/npo_aca/3546821009_k34HTwIi_16ECA780EC868DEAB080EB8AA5EC84B1EBB3B4EAB3A0_EAB080EC9DB4EB939CEB9DBCEC9DB828ED95A9EBB3B829.pdf?msclkid=d2a8fde7cf5811ecb775608b0dcae7bb (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Road Facilities Division, Seoul Metropolitan City. Seoul Road Facility Statistics. Available online: https://data.seoul.go.kr/dataList/261/S/2/datasetView.do# (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Zaharia, R.; Zaharia, R. Triple Bottom Line. In The Palgrave Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021; pp. 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webel, C.; Galtung, J. Handbook of Peace and Conflict Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Han, G.S.; Shin, S.J. A cultural profile of Korean society: From vertical collectivism to horizontal individualism. Korean J. Psychol. 1999, 13, 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, B.S. Utilization of Unused Space in Subway Stations. Available online: https://www.si.re.kr/sites/default/files/2018-CR-01-08_0.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Han, S.H.; Seo, C.W. A study on the possibilities and institutional burdens of the use of underground space as a substitute of land surface. Korean Real Estate Acad. Rev. 2003, 21, 179–190. [Google Scholar]

| TBL | Criteria |

|---|---|

| (A) Social | Is there a program addressing specific regional issues? |

| (B) Economic | Is there an independent space in place for the organization to perform its operations? |

| (C) Environmental | Are the environmental characteristics of the underpass utilized? |

| No. | Category | Renovation Date | Project Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Youth | 2016 | Comma |

| 2 | 2019 | Underland | |

| 3 | 2020 | The Meet Up Center | |

| 4 | Local residents | 2013 | The Village Art Factory |

| 5 | 2019 | The Hwigyeong Atelier | |

| 6 | 2021 | The Musical Instrument Library | |

| 7 | Vulnerable populations | 2014 | The Seoul Indie Platform |

| 8 | 2018 | The Seoripul Gallery | |

| 9 | 2018 | The Chungmu Startup Cube |

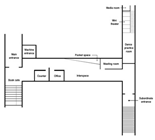

| Name | Comma | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Address | 444-2, Seongsan-ro, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul |  | |

| Renovation Date | 2016 | ||

| Area | 524 m2 | ||

| Main User | Youth (9–24 years old) | ||

| Space Program | Rest area, small concert hall, program room, media room, learning space, etc. | ||

| Site History (Source: National Geographic Information Institute) |  |  |  |

| 1977 | 1978 | 2014 | |

| (a) Social | This is one of the youth-only spaces in Seodaemun-gu. Here, young people lead the operation. This space strives to communicate with the local residents and offers young people the opportunity to experience several different activities that are not taught in school, such as media production. By providing psychological tests and counseling services to teenagers with concerns, it also serves as a local youth safety net. | ||

| (b) Economic | The Nowon-gu local government supports the budget, and it is operated by Seodaemun Youth Counseling and Welfare Center. | ||

| (c) Environmental | In Sinchon, where Comma is located, there are several prestigious universities, making the connection between young people and college students easier. Additionally, since it is a busy street, many young people frequently visit this place. Moreover, it is easily accessible from many areas thanks to its excellent traffic connections. | ||

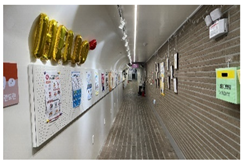

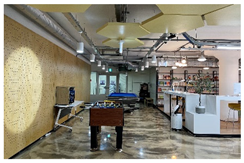

| Photos (Source: Author) |  |  |  |

| Name | Underland | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Address | 86, Gukjegeumyung-ro, Yeongdeungpo-gu, Seoul |  | |

| Renovation Date | 2019 | ||

| Area | 853.79 m2 | ||

| Main User | Teenagers | ||

| Space Program | Book café, powder room, camping zone, arcade, playroom, etc. | ||

| Site History (Source: National Geographic Information Institute) |  |  |  |

| 1977 | 1978 | 2007 | |

| (a) Social | During a meeting meant to provide young people with a chance to participate in local policies, the young people in Yeongdeungpo-gu selected a youth-only leisure place as the most necessary facility in the region. Underland fulfills such wishes of the local youth by providing public spaces for reading, playing, games, and various other leisure activities that are not available within the traditional institutional education systems. | ||

| (b) Economic | All local governments in Seoul are legally required to support and foster youth activities in accordance with the Framework Act on Youth and Youth Protection Act. Installation and operation of youth facilities are specified in the basic ordinances of local governments. Underland is an independent youth facility in Yeongdeungpo-gu and is operated with the support of local governments. | ||

| (c) Environmental | Located in the heart of Yeouido’s residential area, Underland is adjacent to all of Yeouido’s schools (within a 1 km radius). Furthermore, the underground space provides an environment where young people can enjoy various amusement facilities without being too concerned about the surroundings. | ||

| Photos (Source: Author) |  |  |  |

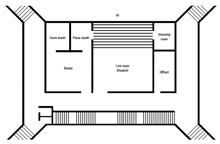

| Name | The Meet Up Center | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Address | 11-2, Choansan-ro, Nowon-gu, Seoul |  | |

| Renovation Date | 2020 | ||

| Area | 672 m2 | ||

| Main User | Local youth and residents | ||

| Space Program | Comic café, mini-theater, performance practice room, single media room, etc. | ||

| Site History (Source: National Geographic Information Institute) |  |  |  |

| 1995 | 1996 | 2009 | |

| (a) Social | In Wolgye-dong, this space was created exclusively as a youth center to promote the growth, happiness, and interaction of the local youth. It offers various growth programs in cooperation with nearby schools. As of 2021, these programs address both the needs of the local youth population and expands to businesses for the revitalization of the local community. The Meet Up Center has been operating as a place where the local youth and residents meet and interact. | ||

| (b) Economic | This place is supported by the local government of Nowon-gu and operated by the Blue Tree Foundation, a non-profit NGO for youth in South Korea. | ||

| (c) Environmental | The Meet Up Center is located in an apartment complex near other residences. Moreover, it is characterized by a unique location that is near two universities, six elementary schools, four middle schools, and five high schools (within a 1 km radius), indicating a high population of young people in the area. Moreover, a library and a sports center are located right near the center, with regional characteristics that enable close connections to local resources. | ||

| Photos (Source: Author) |  |  |  |

| Name | The Village Art Factory | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Address | 384, Songpa-daero, Songpa-gu, Seoul | ||

| Renovation Date | 2013 | ||

| Area | 727 m2 | ||

| Main User | Local residents | ||

| Space Program | Book rental space, movie theater, program room, office, etc. | ||

| Site History (Source: National Geographic Information Institute) |  |  |  |

| 1995 | 1996 | 2013 | |

| (a) Social | The Village Art Factory was created as a space for autonomous cultural and arts activities. It provides club projects, rest areas, various life-education and culture and arts programs for local residents. | ||

| (b) Economic | Songpa-gu supports residents’ voluntary art and hobby activities, and the Village Art Factory is operated directly by the district. | ||

| (c) Environmental | Located between the Songpa Station and the Seokchon Station, it is easily accessible within the region. Based on this advantage, a variety of art and cultural programs are offered to residents in nearby areas. Furthermore, environmental projects have been implemented in the region by combining environmental movements and living cultures with the object of protecting the environment and nature. | ||

| Photos (Source: Author) |  |  |  |

| Name | The Hwigyeong Atelier | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Address | 55, Mangu-ro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul |  | |

| Renovation Date | 2019 | ||

| Area | 375 m2 | ||

| Main User | Local residents | ||

| Space Program | Café, program room, office, lecture hall, etc. | ||

| Site History (Source: National Geographic Information Institute) |  |  |  |

| 1991 | 2008 | 2019 | |

| (a) Social | The Hwigyeong Atelier was built in Dongdaemun-gu as a center for village revitalization. It serves as a hub for community building and supports village activities, providing residents with various life-education programs and rest areas. | ||

| (b) Economic | The village revitalization center project was implemented in accordance with the Seoul Metropolitan Government Ordinance on Support for the Creation of Village Communities. The Hwigyeong Atelier is operated by private consignment by the district. | ||

| (c) Environmental | Thanks to its location on a main street near the Hwigyeong Station, this atelier enjoys good regional access. Thus, efforts have been made to bring various underground programs to the land surface so that they do not remain solely and invisibly underground. By holding a flea market on the main street, which features items donated by the local residents, music performances and busking, the atelier hopes to penetrate the region. | ||

| Photos (Source: Author) |  |  |  |

| Name | The Musical Instrument Library | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Address | 326, Olympic-ro, Songpa-gu, Seoul | ||

| Renovation Date | 2021 | ||

| Area | 290 m2 | ||

| Main User | Local youth and residents | ||

| Space Program | Studio, music studio, small performance hall, storage space for musical instruments, etc. | ||

| Site History (Source: National Geographic Information Institute) |  |  |  |

| 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | |

| (a) Social | Generally, playing a musical instrument ranks high on the list of activities with a high barrier to entry. There is an economic burden involved in all stages, from purchasing the instrument to managing it and taking lessons. To enable residents to learn an instrument, Songpa-gu loans and manages a variety of musical instruments at a very low price. Furthermore, it utilizes relevant human resources in the area and provides space for music practices, making various lessons available. | ||

| (b) Economic | As part of the Songpa-gu specialized education model project, it is operated with local government support. The local residents donate musical instruments to the library, allowing it to own more instruments and to hire music professionals to teach. | ||

| (c) Environmental | The old underpass, which was not frequently visited, had become one of the most hideous places in the region. Given the crosswalks above ground, people do not have to use this underpass. On top of providing practical spaces such as libraries and studios, The Music Instrument Library forms a harmonious relationship with the underpass. There is a passageway inside the musical instrument studio, which serves as an extended performance area. Musical instruments for rent are interactively displayed with a hologram that allows citizens to hear the instrument’s sound when they touch the glass. In addition to its original purpose, the Musical Instrument Library adds fun and a sense of aesthetics to the urban environment. | ||

| Photos (Source: Author) |  |  |  |

| Name | The Seoul Indie Platform | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Address | 238, Mapo-daero, Mapo-gu, Seoul |  | |

| Renovation Date | 2014 | ||

| Area | 590.8 m2 | ||

| Main User | Independent musicians and residents | ||

| Space Program | Live performance hall, studio, workroom, multipurpose hall, etc. | ||

| Site History (Source: National Geographic Information Institute) |  |  |  |

| 1996 | 1997 | 2006 | |

| (a) Social | It offers halls for live performances, recording studios, workshops for individuals and bands, and multipurpose halls for various gatherings and events, all at below standard market prices. In addition, various projects are carried out to support the creative activities of independent musicians. | ||

| (b) Economic | As the Mapo Cultural Center was seeking to relocate its facilities, Mapo-gu planned a project to renovate the Ahyeon underpass, which no longer served its function, as a facility for music creation. Accordingly, the space was built as part of a remodeling project for a music creation space and included funding from the Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism and the local government (Mapo-gu). It is currently operated by the Mapo Cultural Foundation. | ||

| (c) Environmental | Mapo-gu’s Hongdae is the district that produces the Korean indie culture; however, when the Seoul Indie Platform was created, independent cultural artists working in Hongdae started to leave because of increasing gentrification. To preserve Mapo-gu’s art culture, the Seoul Indie Platform was established to ensure that musicians do not completely leave their homes. In addition to being equipped with unique locational characteristics that are suitable for indie musicians’ creative activities, the underground space has also become a cultural space that presents performances by independent musicians. | ||

| Photos (Source: Author) |  |  |  |

| Name | The Seoripul Gallery | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Address | 1, Nambusunhwan-ro 323-gil, Seocho-gu, Seoul |  | |

| Renovation Date | 2018 | ||

| Area | 522 m2 | ||

| Main User | Young artists (aged 19~39) and local residents | ||

| Space Program | Exhibition space, multipurpose hall, collaboration space, office, etc. | ||

| Site History (Source: National Geographic Information Institute) |  |  |  |

| 1988 | 1989 | 1999 | |

| (a) Social | This space not only provides exhibition opportunities for young artists aged 19 to 39 but also supports various cultural programs (cultural performances, dialogues with artists, art programs, curator talks, etc.) that are linked to the exhibitions. It aims to create various jobs through this process. | ||

| (b) Economic | In 2017, as Seoul’s urban regeneration and job creation projects began in earnest, the Seoripul Gallery was selected for the cooperative job creation project contest. Therefore, it received initial support from the Seoul Metropolitan Government. It is currently operated by local governments in partnership with the Seocho Cultural Foundation. | ||

| (c) Environmental | The Seoul Arts Center is Korea’s largest comprehensive arts facility, comprising a concert hall, an opera house, and an art gallery. It was designed to take on a core function for promoting Korean art. Therefore, it is a gathering place for numerous art groups and is frequented by countless visitors interested in experiencing various art activities. The space is in harmony with the local environment; it was created by transforming an underpass, which was a neglected passageway linking to the Seoul Arts Center, into a place where young artists can present their works to visiting citizens. | ||

| Photos (Source: Author) |  |  |  |

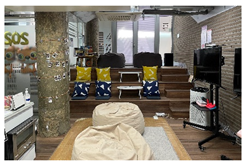

| Name | The Chungmu Startup Cube | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Address | 265, Toegye-ro, Jung-gu, Seoul |  | |

| Renovation Date | 2018 | ||

| Area | B1 594 m2, B2 567 m2 | ||

| Main User | Young entrepreneurs (aged 19–39) and local residents | ||

| Space Program | Café, shared sample training center, office, start-up room, etc. | ||

| Site History (Source: National Geographic Information Institute) |  |  |  |

| 1984 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| (a) Social | The Seoul Metropolitan Government and all autonomous districts have enacted ordinances to support youth startups. In fact, the relevant law requires local governments to come forward and facilitate youth startups and set up support centers. Accordingly, Jung-gu has supported the Chungmu Startup Cube, a center for youth startups. | ||

| (b) Economic | The Chungmu Startup Cube is a local government-run support center that provides various programs for youth startups. It is a project that is fully consistent with local government efforts to support youth start-ups, so legally guaranteed support can be obtained. Creating space in this way increases the sustainability of the project in connection with the region’s local resources from the central business district and the traditional manufacturing streets. | ||

| (c) Environmental | Seoul’s central business district, Jung-gu, is home to a variety of commercial, social, and cultural transportation facilities. While it provides a good network for business activities, the land prices are high. The Chungmu Startup Cube provides a variety of geographic advantages to break down these barriers and assist startups. Euljiro and Cheonggye-ro near the center are representative areas for manufacturing facilities in Seoul, and various companies are coming to the area to test ideas and prototypes, creating a hub for young startups. | ||

| Photos (Source: Author) |  |  |  |

| Old | New |

|---|---|

| functional | emotional |

| supplementary | independent |

| new development | development of unused spaces |

| an isolated space of innovation | connected daily spaces |

| Characteristics of Seoul | TBL | SCT Underpass Development |

|---|---|---|

| Deepening urban polarization due to the lack of public spaces | (A) Social | a program to solve regional problems |

| Promoting local community revitalization policies | (B) Economic | local government support |

| “Slummized” underpasses | (C) Environmental | Utilizing the benefits of unused underground resources |

| No. | Project Name | Project Value | Social Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Comma | Support for youth in self-governing activities and counseling | Support the healthy development of youth |

| 2 | Underland | Youth-only leisure facilities | |

| 3 | The Meet Up Center | Provision of education that is Insufficiently experienced in institutionalized education | |

| 4 | The Village Art Factory | Promote networking among village artists and the local community | Create and support local communities |

| 5 | The Hwigyeong Atelier | Create and support local communities | |

| 6 | The Musical Instrument Library | Lend and teach how to play instruments to local residents | |

| 7 | The Seoul Indie Platform | Support for independent musicians | Promote appropriate balance and harmony between mainstream and non-mainstream |

| 8 | The Seoripul Gallery | Support for young artists | |

| 9 | The Chungmu Startup Cube | Support for young adults’ entrepreneurship |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, D.Y.; Kim, H.J. Sustainable Development of Underutilized Pedestrian Underpass in Seoul. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137878

Jeong DY, Kim HJ. Sustainable Development of Underutilized Pedestrian Underpass in Seoul. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137878

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Dae Yeong, and Hee Jin Kim. 2022. "Sustainable Development of Underutilized Pedestrian Underpass in Seoul" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137878

APA StyleJeong, D. Y., & Kim, H. J. (2022). Sustainable Development of Underutilized Pedestrian Underpass in Seoul. Sustainability, 14(13), 7878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137878