1. Introduction

This paper examines the contribution of Regional Design (RD) in the construction and diffusion of spatial imaginaries (SI) concerning the present and future of our metropolitan cities.

Imagining the world with different characteristics to those we see is not only an individual mental practice: when imagination works at an intersubjective level, acting as a form of collective imagination, it is known as “common consciousness” [

1] or “social imaginary”, referring to how people imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how situations arise between them and their fellow citizens, the expectations that are normally met, and the deeper normative notions and images underlying such expectations [

2].

Historically, the spatial dimensions of imaginaries have been captured by images (ideograms, maps and cartographies) representing the actual territories and their expected development in the near future. This activity pertains to urban and regional planning, and aims to institutionalise these imaginaries in discursive, normative and drawn documents (maps, ideograms etc.). Seen from a spatial dimension, visioning through maps has traditionally been a powerful tool in the constitutive imaginary of governments seeking to define or contest the limits of their political reach [

3].

The expansion of urban populations, facilitated by improved mobility, interconnectivity and infrastructure technologies, has fuelled a particular interest in understanding whether spatial planning can facilitate visioning at larger-than-local scale, for instance in metropolitan cities, city-regions, mega-cities or a megalopolis [

4,

5,

6].

Lastly, the recent coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 pandemic that spread across cities, regions and countries has challenged the perceived geographies of spatiality, from “stay home” measures to the use of drones and roadblocks to enforce lockdown by limiting movement in certain regions. In particular, the pandemic has challenged both individual and collective perceptions of the city and its regional context. While discussions on the effects of the pandemic on regional design have already started [

7], few contributions have indirectly assessed the effect of the pandemic on SI: early evidence [

8,

9] shows that travel restrictions, “stay home” measures, physical distancing, and limitations on the use of public space have challenged the perception of the city, and in particular its public spaces, by challenging each person’s “sense of place” [

10].

The new challenges emphasised by the pandemic for the planning of cities and their regional contexts imply that even when the scale and complexity of the context and actors change, spatial imaginaries and their construction are still important issues that play a key role in guiding governance relations within spatial planning practices.

This paper focuses on RD as an imaginative and creative method aimed at the co-production of actual and future visions of a metropolitan city or a region through the application of design methodologies at a larger-than-local scale. Despite recent studies on the positioning of RD in planning theories [

5,

11] and its performance in planning practices [

6,

12], an in-depth understanding of the interrelations between regional design and spatial imaginaries has not yet been achieved.

Moreover, empirical evidence on the expression of spatial imaginaries in governance rescaling processes is focused on the role of “space imaginaries” in the design of regions for purposes of planning and economic development, rather than on the capacity of planning practices to grasp, guide and eventually influence such spatial imaginaries, whose fluidity and openness lead to processes of creation and destruction.

In light of these gaps, this paper aims to explore the relationship between planning and the spatial imaginaries that are expected to be realised by spatial planning and, in particular, by regional design processes (through cartographic/metaphoric representations and narratives), which differ in scales, geographies and governance contexts [

6].

After positioning the discussion within the existing literature relating to planning and geography, by defining the nexus between regional design and spatial imaginaries (

Section 2), the paper proposes evaluating the performativity of regional design in grasping and eventually changing spatial imaginaries, through its capacity to make SI visible, provide insight and new SI, and even enhance institutionalisation (

Section 3). Analysis under these lenses is provided through a mix of methodologies targeted at defining the performance of RD and the performativity of SI (

Section 4).

This analytical framework is tested by a case study in which spatial imaginaries have changed over time and have been challenged by an RD process (

Section 5). The analysis focuses on the metropolitan city of Florence: its strategic plan was defined through an RD process which aimed to establish a vision capable of combining multiple and even contrasting spatial imaginaries, deriving from the non-correspondence between the functional and institutional boundaries of the metropolitan city. An analysis of the consolidated and recent development of spatial imaginaries of the metropolitan city is developed in view of the analytical framework: the results (

Section 6) use evidence provided by the strategic planning process and the current pandemic context to reflect on the roles of regional design in defining and/or consolidating the spatial imaginaries of the metropolitan city and its future. Finally, directions for further research and practices are highlighted, concerning the contribution of regional design in grasping and orienting spatial imaginaries.

2. Regional Design for Grasping Spatial Imaginaries

Regional design is a process-led methodology, embedded in a long-term development and planning process and capable of taking into account the systemic nature, process-orientation, and entrepreneurial regime of regional development [

13]. In this process, the large number of actors involved, their multi-scalar networks and unclear responsibilities imply that the strategic framing of the region and its future should employ a collaborative approach by involving inter-disciplinary experts as well as regional stakeholders and local citizens in complex inter-relations, to generate new dynamics for regional planning and enable a re-scaling of governance arrangements aimed at operationalizing the inter-scalar, relational notion of space [

6].

However, implicit in much of spatial planning and regional design research is the idea that spatial representations of actual and future spaces and places in different forms (from maps to ideograms and metaphors) are representative of collective spatial imaginaries. Literature on the role of visualization and visioning in spatial planning takes for granted the capacity of images to intercept such imaginaries and use them as institution builders [

14]. Nevertheless, emphasis is placed on the role played by spatial imaginaries in governance rescaling processes [

15,

16], in developing a ‘brand’ that is outside existing political and territorial imaginaries [

17,

18], and in formulating alternative political visions in an age of digital technologies of control and regulation, in which new forms of mapping stress the need to rethink assumptions of power and knowledge [

3,

19].

Conversely, human geographers have proposed conceptualizations and the empirical verification of spatial imaginaries [

20] as representational discourses about places and spaces, linked to contextualized situations such as colonialism [

21,

22] or post-industrial cities like Detroit [

23]. Spatial imaginaries are connected to distance (in time and space, and in culture and lifestyle), scales or “spatial orderings” [

20] and collective emotions: by spreading ideas about people, places, politics and the environment they express social concerns and common uncertainties about the future [

24]. While the existing literature largely focuses on the social construction of spatial imaginaries, looking at the representational dimension of spatial imaginaries, a few geographers define them as performative [

20,

22,

25].

On this basis, Davoudi [

26] proposes approaching spatial imaginaries in planning with a dialectical combination of the two standpoints. Taking a relational view of space and place [

27], spatial imaginaries are defined as “deeply held, collective understandings of socio-spatial relations that are performed by, give sense to, make possible and change collective socio-spatial practices. They are produced through political struggles over the conceptions, perceptions and lived experiences of place. They are circulated and propagated through images, stories, texts, data, algorithms and performances. They are infused by relations of power in which contestation and resistance are ever-present” [

26] (p. 101).

These power relations are influenced by spatial representation. The efficacy of visualization as the “capacity for certain representations to win over public opinion” [

28] (p. 252) and to co-ordinate action [

29] is related to its persuasive power, especially when disclosing planning policies to the general public, outside the professional sphere [

30].

The efficacy of spatial imaginaries lies in their institutionalisation. This term is widely used in social theory to refer to the process of embedding concepts, social roles, values or modes of behaviour within an organization, social system, or society as a whole [

31]. The institutionalisation of spatial imaginaries covers their capacity to travel across significant institutional sites of urban and regional governance. This idea of travelling framing ideas, i.e., the use of images, metaphor and narratives, intentionally conceived as “travelling metaphors” [

32,

33], provides useful insight into the capacity of images to move between different planning and institutional levels, from local to regional and back, and between different planning and governance modes, from soft to statutory and back [

34].

Within this overview, literature concerning regional design can provide useful insight into the capacity of RD to enhance spatial imaginaries. As a matter of fact, regional design as an imaginative and creative practice is expected, among many other achievements, to enhance the quality of both spatial planning strategies and governance settings: “It is supposed to clarify political options, forge societal alliances, and remove conflict around planning solutions during early moments of decision-making and speed up their implementation in this way” [

12] (p. 13).

With these expectations, the evaluation of RD′s contribution to the enhancement of spatial imaginaries is especially interesting in relation to the approach recommended by Faludi and Korthals [

35]. Drawing on communicative planning literature, they propose that strategic plans in particular should be evaluated not in terms of whether the means respect the aims, but rather in relation to the planner’s ability to interact with the addressee (politicians, stakeholders, citizens). Considering planning as a learning process, the evaluation of the performance of strategic spatial plans concerns “how they improve decision makers′ understanding of the present and future problems they face” [

36] (p. 300). Within this sociocratic interpretation of planning “the ‘performance’ of plans is in the outcome of negotiation and deliberation: in agreement among actors, and the change of mind that the formation of such consent requires” [

12] (p. 193).

In the search for planning solutions, RD involves this change of mind by combining analytical, political and organizational reasoning with the aim of developing, challenging or refining planning frameworks, leaving ample room for interpretation. Thus, relationships between authors of regional designs and their audiences are key for the performance of a practice that relies on imagination and the representation of what is possible and desired [

37]. Incidentally, while a comparative analysis of expectations regarding the performance of RD and its effects on governance rescaling and institutional building has been undertaken in recent years in different European contexts [

6], analysis of the effects of these processes on the creation, consolidation and change of collective spatial imaginaries is still lacking. The analysis reported in this article explores this aspect.

3. Unravelling the Contribution of RD in Defining, Enhancing and Changing Spatial Imaginaries: An Analytical Framework

Literature on the performance of RD shows that, while there are great expectations about its power to “change the actor′s mind”, the evaluation of its performance in relation to spatial imaginaries has not yet been supported by empirical evidence. In order to fill this gap, this article develops a framework for analysing the impact of regional design on spatial imaginaries, in terms of its capacity to grasp them and even change them. We refer to the debate on both the performativity of spatial imaginaries and the performance of regional design, matching these two sets of literature.

The discussion about the performativity of spatial imaginaries has paved the way for ”more direct analysis of material practices, and considerations of how material practices directly form and modify spatial imaginaries” [

20] (p. 519). In particular, Davoudi suggests focusing on the ”role of space and place in the construction of social imaginaries” [

26] (p. 97). Given this assumption, though much work on imaginaries adopts a discursive analysis method, some cases have dealt with analysing the performativity of spatial imaginaries, with different approaches and outcomes. Hinks et al. [

16] linked soft space imaginaries to the process of region-building, with the presumption that the study of present-day regional institutions and policy initiatives should not ignore the often complex legacy of past region-building efforts, even those that are considered obsolete and dismissed as being of mere historical interest. Spatial imaginaries are subject to processes of creation and destruction: they can be replaced by a new imaginary that has gained primacy in the meantime and, in some cases, they can be re-appropriated later and reenergized, even in transfigured forms [

38]. Metzger and Schmitt [

39] illustrate how creative advocacy helped to secure legitimacy for the Baltic Sea region soft space as advocates aligned resources and political capital in support of a potent interregional imaginary. Sykes [

40] referred to these themes of analysis and their articulation with, and through, material spaces, places, and practices, to develop his interpretations of the role of imagined and material space in the UK’s debate about Brexit. Davoudi & Brooks [

41] analysed the role of SI within the politics of scalar fixing.

However, these studies were focused on the role of “(soft) space imaginaries” in the “phased” building of regions for planning and economic development purposes, rather than on the capacity of planning practices to grasp and orient such spatial imaginaries.

Conversely, literature on RD has mainly focused on defining its position in the context of planning theories [

5,

12] and its performance has been analysed in the field of practice [

11,

13,

42] as a method in which the imagining and envisioning of spatial futures of regions enhances planning and governance at regional and supra-regional levels [

6,

37].

By comparing these two aspects of the literature, we developed a framework for analysing the role that regional design can play in enhancing or changing spatial imaginaries, involving different and even competing imaginaries and their consolidation through institutionalisation processes (

Table 1).

Regional design is a methodology that helps to

make spatial imaginaries visible, by visualising the different spatial dimension of imaginaries of a region, as well as its future development. “Regional design may serve as a practice to critically reflect the region as a political and social construct. For this purpose, […] regional design should analyse, map, and design alternative functionalities, histories, and identities of a region, and thus help to imagine a region beyond a pure economic logic” [

37] (p. 12).

In terms of scale detection, RD helps to define the appropriate scale at which policy issues should be situated and addressed. In this process of scalar re-structuration, regional design practices, by providing images, scenarios and visions, are expected to enhance spatial imaginaries contributing to the territorial, symbolic and institutional shaping of a region [

48]. This could be connected with the process of “strategic framing” defined by Healey as the act of creating an orientation, i.e., framing and identifying critical actions by recognizing strategies through a process of “evocation, visualization, naming and framing” [

49] (pp. 188–189), which requires “intense simplification and selectivity” [

50] (p. 449).

RD contributes to strategic framing by putting on paper the different spatial imaginaries of the region and highlighting their integrations and critical issues. While on the one hand this can elicit strife between conflicting imaginaries, on the other hand it helps to establish regional narratives that can become important drivers for regional discourse [

37] (p. 22) based on SIs.

As a matter of fact, due to their nature, Spatial Imaginaries transcend regional boundaries: analysis of the imaginaries of different cities such as Toronto [

43] or Manchester [

15] show that the boundaries of the region are not fixed and connected to institutional borders, but vary widely according to the stakeholders concerned and their everyday lives and experiences, as well as their policy objectives.

Within these fuzzy boundaries and scales of perceived regions, Davoudi & Brooks connected the performativity of SI to the process of scalar fixing: “the remarkable staging power of imaginaries lies in their blurring of perceived facts and fictions and of precision and fuzziness in the political processes of scalar fixing. Through the fusion of material and discursive practices, scalar imaginaries are performed, given meanings and become taken for granted, collective understandings of what and where a particular scale is” [

41] (p. 54).

Secondly, by providing new analytical perspectives on the region and exploring new forms of spatial, functional and temporal organisation, RD provides insights into different and even new spatial imaginaries. Within this process, new images and perspectives for the future of the region can arise.

Performance of RD is thus linked to representation and the use of imagery for new readings and understandings of the region, and leads to new and innovative prefigurations of its future.

As the performance of imagery is closely connected with its narrative nature and the storylines it implies, reasoning in and through imagery broadens the horizon of discussions. Despite the fact that design imagery may be provocative, the performance of maps, models and other spatial representations is not easy to predict [

37]. Thus, RD may help to reveal new ways of perceiving the region and make them evident to their different advocates by providing “moments of insight” in which stakeholders start to see the areas, their problems and their futures from different perspectives. Through the designs produced in a regional design process, or while participating in a design meeting, new understandings occur in the form of both individual and collective shifts of perspective [

42]. Within this process, RD can even help to change an actor’s mind and, consequently, shift policy objectives and the logic of policy rationale [

46]. Such changes can lead to or result in a change to spatial imaginaries, SIs being confronted with resistance or contestation [

45] of previous and existing spatial imaginaries and “taken-for-granted assumptions” [

26] (p. 105), with tension regarding the re-imagination of what might come [

16]. Moreover, being contingent and dynamic, SIs provide insight into the future in the present: “Spatial imaginaries not only enable and legitimise material practices through representation. They also are enacted and maintained by these practices […]. Planning tools such as maps, images, diagrams and scenarios do not simply represent an urban future. They also perform the future in the present, and by doing so they essentialize a specific imaginary of urban futures which has material consequences for how cities are planned, redeveloped, invested in and reimagined” [

26] (p. 103).

As a third aspect,

regional design enhances the institutionalisation of SI. RD boosts institutional and organisational capacity by enhancing imaginative capacity. Images, metaphors and narratives produced within the framework of an RD process are expected to address and influence stakeholders’ imaginaries. Within this process, RD is the linking element between soft and hard governance modes and connected planning instruments at all levels [

34]. Given its nature of interstitial planning [

5], it acts as a sort of “free way” to enable images to travel between planning scales and modes [

34].

The final result of this process of moving between scales and planning levels is the institutionalisation in formal documentation or in policy or strategy of images of the present status and the future of a territory.

Moreover, regional design can act at a softer level, leading to or enhancing the process of appropriation of such images.

The evaluation of the performance of RD in this case is twofold: it concerns both the insertion of spatial imaginaries into a strategic planning document, a memorandum of understanding or a partnership agreement, and the process by which SI become part of the collective imaginary, entering into current narratives and policy discourses.

In order to analyse this process, two concepts from the SI literature can be helpful: repetition and resonance. According to Patomäki and Steger, “imaginaries acquire solidity through the repetitive performance of their assigned qualities and characteristics, as well as through the social construction of the space of everyday practices” [

47] (p. 1057).

For an SI to be institutionalised, it needs to persist within the mechanisms of competition among different and even overlapping spatial imaginaries, and resonance allows it to win them over: “For any soft space imaginary to gain traction, then, it will need to compete with previous and parallel imaginaries, including those of territorial government or other soft spaces […]. The more resonance a particular imaginary has at multiple sites and scales, the more likely it is to be translated into tangible strategies, practices or projects” [

15] (p. 645).

The concepts of “repetitive performance” and “resonance” can open up interesting perspectives for analysing how spatial imaginaries, through RD processes, travel across scales and planning processes, and are institutionalised into planning instruments and policies, becoming part of collective imaginaries.

Comparing the RD and SI literature, these concepts of resonance and repetition can also answer the claim made by Kempenaar et al. [

42] in their analysis of RD’s long term effects, in this case concerning the “long-lasting” nature of SI over time and after great changes and challenges, such as the current pandemic. Therefore, taking the pandemic into due account when evaluating the performance of RD in defining, enhancing and changing spatial imaginaries can provide useful insights into the repetition of the performance of spatial imaginaries and the “travelling” capacity of the metaphors on which they are based.

4. Methods

Given the theoretical approach and the analytical framework, our empirical approach was based on methods of analysing regional design performance and methods of identifying and analysing the performativity of spatial imaginaries.

The analysis of planning imagery [

12,

29,

51] within planning documents, maps and tests reveals details planning issues that have been addressed by regional planning or design processes, and their evolution over time. Reviews of documents referring to RD initiatives, such as the working programme of the RD process, discussion notes, tenders and briefs, ex-post evaluation of the studio’s work [

51] and reports of the participatory process, provide insights into the expected performance of the design process. In general terms, changes to the spatial imaginaries of a region can be deducted by analysing “changing policy objectives, organizations authoring documents, the status and audience of publications and degrees of formality of policies” [

46].

Moreover, stakeholders’ and practitioners’ evaluations of regional design-led approaches can be identified through semi-structured interviews with key actors [

42]. Researchers’ participation in the process can bring added value as they can provide in-depth information on the use of spatial representations in policy rationale [

46].

The debate on the performativity of spatial imaginaries, based on a direct analysis of how material practices directly form and modify spatial imaginaries [

20] and the political projects they serve [

41], can provide useful insight into the analysis of SIs emerging in an RD process.

The framework developed by Hincks et al. [

16] analyses competing soft space imaginaries that emerged and were consolidated during the process of region-building, which is considered a socio-spatial construct. Applying methodological approaches of “critical discourse analysis”, Crawford [

44] (p. 74) defined a framework for the analysis of spatial imaginaries, to be conducted through targeted interviews and the examination of policy documents. Within this framework, Sykes [

40] approached the analysis of SIs by referring to the definitional and analytical themes connected to the scale, ‘type’, performativity and materiality of imaginaries.

Finally, while analysing the performativity of SIs in scalar fixing, Davoudi & Brooks [

41] (p. 54) “propose to consider the political project as the why of fixing (what political goals are pursued), the scalar fix as the what (what scale is enacted as best serving the political goal), and the scalar imaginaries as the how (what are the key drivers through which the fixing is pursued, and by whom)”.

We propose applying the analytical framework through a mixture of these methods, as reported in

Table 2. The research we undertook under these lenses was aimed at understanding how a regional design process is challenged by and challenges existing spatial imaginaries. For this purpose, the visions defined by the regional design process and the connected narratives were examined against the spatial imaginaries to which they were connected analysing how they changed both in the documents and in the policy rationale. In particular, the analysis of the evolution of spatial imaginaries proposed by Hincks et al. referred to documents that institutionalise them, and the underlying narratives which indicate the key drivers that led to such institutionalisation.

We assumed a “case study approach” [

42], with the case of the strategic plan for the metropolitan city of Florence chosen as emblematic due to the density of the spatial imaginaries that have concerned the city region over time, and which showed the greatest splendour in the Renaissance period.

Over the centuries, the theme of “rebirth” has been the leitmotif of the policies adopted by the capital city and other cities in the functional area, shaping their spatial imaginaries. The analysis of the case study was carried out on the basis of experience gained in the Regional Design Lab (ReDLab, Florence, Italy) of the University of Florence, Department of Architecture, which accompanied the Metropolitan City in defining the vision of the strategic plan, by applying a regional design process.

In the results monitoring phase, the research aimed to evaluate the performance of the process in relation to changes in the spatial imaginaries. However, during the research period, the pandemic occurred and provided useful elements to evaluate the third aspect of the methodological framework, concerning the institutionalisation of SIs in terms of repetition and resonance.

In-depth information about the changes and challenges for metropolitan spatial imaginaries during the monitoring of the strategic metropolitan plan and during the pandemic was obtained, since the author was in charge of scientific consultancies for both the Metropolitan area and the capital city. At the metropolitan level, the ReDLab was engaged in the definition of the Metropolitan Territorial Plan as an implementing instrument for the strategic plan; the Municipality of Florence, during the pandemic, launched the public consultation “Rinasce Firenze”. The ReDLab was tasked with understanding changes within the spatial imaginaries of the city’s future and their connection with the participatory process for the municipal land use plan, and with funding policies in the framework of the cohesion policy and the recovery fund provided for the pandemic crisis. Finally, the ReDLab participated as a contractor of the Municipality of Florence in the Targeted Analysis “ESPON METRO-The role and future perspectives of Cohesion Policy in the planning of Metropolitan Areas and Cities” [

52]. Although it was not the author’s original intent to conduct the research presented in this paper, these processes provided much data (450 contributions to “Rinasce Firenze”, 8000 answers to the questionnaire for the Municipal Land Use Plan, and ten targeted interviews with metropolitan stakeholders within the framework of the ESPON METRO project) that has fuelled our analyses of the long term effects of RD on the spatial imaginaries of the metropolitan city.

5. The Metropolitan City of Florence between Consolidated and New Spatial Imaginaries

Although the establishment of metropolitan cities has been under discussion since the post-war period [

53], metropolitan cities in Italy only came into play within the framework of the “Delrio law” (Law 56/2014), which superseded fourteen provinces incorporating major regional capital cities with “metropolitan cities”. This scheme was introduced in order to adopt a new spatial planning instrument, the Metropolitan Strategic Plan (MSP), to manage the metropolitan cities’ development by promoting and managing services, infrastructures and communication networks in an integrated way.

The Metropolitan City of Florence (MCF) is composed of 41 municipalities; its population slightly exceeds one million inhabitants.

Since its institution in 2015, the lack of correspondence between the administrative boundaries and the functional socio-economic dynamic within the area has been evident to administrators, citizens and regional scientists [

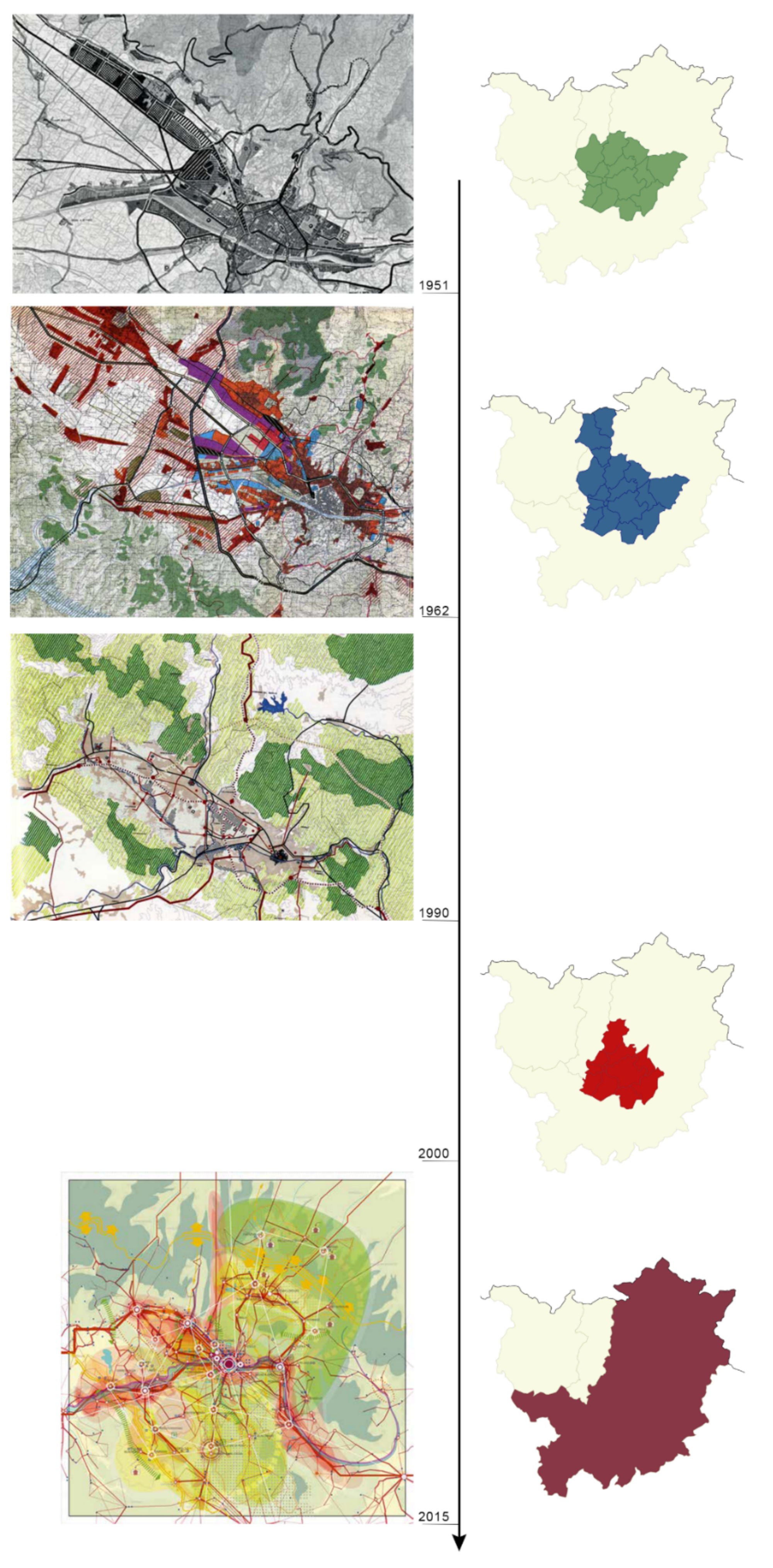

54], and institutional borders seem to deny the consolidated spatial imaginaries of the metropolitan area.The MFC resulting from the Delrio law involves territories with a strict identity (Chiantishire, the Mugello mountains, Elsa Valley) that do not feel they belong to the metropolitan city of Florence. The city’s spatial imagery is linked to the conurbation localised on the Arno plain and has been the focus of previous regional planning instruments and economic programming strategies since the post WWII period (

Figure 1).

5.1. Consolidated City-Regional Spatial Visions

Evidence of the dynamics of an increasingly integrated and interconnected conurbation on the Arno plain has arisen since a regional analysis was undertaken for the local land-use plan for the City of Florence in 1951. The planning process was based on the definition of an initial inter-municipal planning scheme concerning 13 municipalities joined by the hypothesis of linear development on an “equipped axis” connecting the cities of Florence, Prato and Pistoia along the flat plain of the Arno Valley. The proposal for an Inter-Municipal Plan in 1962 strengthened the narrative of the equipped axis, merging 16 municipalities by depicting the infrastructural and functional layout of the plain as a polycentric system connected by infrastructural axes. De Luca et al. report that “This image, although it was never approved by the Region or by local and inter-municipal authorities, acted as a guideline for the positioning of enhancement infrastructures such as the railway axes, parks and industrial parks in the cities of Sesto Fiorentino (part of the first belt of Florence) and the city of Prato, along the highway” [

53] (p. 249).

The need for coordination emerged in the 1980s in order to face uncontrolled urban and industrial developments in the interstitial spaces within the three main city centres. This is why the Tuscany Region proposed a coordinated territorial plan involving 20 municipalities, the “Structural Scheme for the metropolitan area of Florence, Prato and Pistoia”. This document, approved in 1990, was misaligned with the recently approved national law no. 142/1990, which defined the metropolitan city of Florence as being located within the provincial boundaries and established the Province of Prato: de facto, the delegation of responsibilities to the provinces weakened the implementation of territorial coordination policies in this sub-regional area.

Eventually, in the 2000s the public-private association “Firenze Futura” drew up the “Florence 2010” Strategic Plan, a narrative document based on four main strategic axes of intervention: ‘promoting innovation’; ‘re-balancing the distribution of functions in the metropolitan area’; ‘re-organizing mobility and accessibility’ and ‘improving urban quality as a resource for development’ [

55] (p. 31, author’s translation). Each strategic vision or axis is accomplished by two to four objectives, achieved through diverse projects that were mainly focused on the City of Florence, “envisioned as a cultural centre for branded Italian production and for high-quality handcraft that encourages and manages tourism, promoting a new image related to creativity and technological innovation” [

56] (p. 53). Although this strategic plan mainly targeted the municipality of Florence, it was “supported by massive urban marketing and promotional multimedia campaigns” (ibid.) and represented the rationale for launching the political project of establishing “Greater Florence”, an intermunicipal institution including Florence and the nine municipalities in the first belt (approx. 600,000 inhabitants).

5.2. The New Strategic Plan: Enhancing the Metropolitan Renaissance

As per Law 56/2014, in October 2015 the MFC started to define its strategic plan: a participatory process was launched under the slogan “Together for the plan” which revealed both the stakeholders’ difficulty in defining the “new” metropolitan area and its problems, and the emergence of certain recurring narratives. Aside from the mayor of Florence, who was also governor of the Metropolitan City, most politicians from the other 40 municipalities involved were reluctant to participate in the project, and “large-scale thinking” among citizens only referred to large infrastructures that were already the focus of ongoing conflicts (airport enlargement, together with the location of an incinerator and a high-speed railway station).

In order to overcome this gap, the Metropolitan City of Florence decided to engage in the process of outlining the vision for Florence’s metropolitan area by defining the image of the metropolitan city, both today and in the near future (2030), through the application of a Regional Design process with the support of the Regional Design Lab (Department of Architecture, University of Florence).

In order to avoid the mismatch between institutional boundaries and functional dynamics, a basic representation of the territory as a 100 × 100 km square was chosen as the background for all spatial representations: within this framework, the institutional boundaries of the metropolitan city and the cities of Prato and Pistoia were conceived as a whole, and the green side (80%) of the metropolitan city became prominent.

Differences and divergences regarding the imaginaries of the region were visualised at two different design scales. ‘Macro-stories’ concerned official descriptions, chronicles and design studies of institutional public projects, as well as semi-public and private projects covering public supra-local services: from metropolitan public transport projects (tramways and cycle paths) to agricultural parks. ‘Micro-stories’ were current and evolving projects and practices involving local communities, which emerged from the participatory process through the storytelling technique: they ranged from active solidarity networks and forms of co-housing and co-living in diverse parts of the countryside, to policies that enhanced local values, such as “milk streets” in the Mugello area and the ancient grain supply chains in the plain.

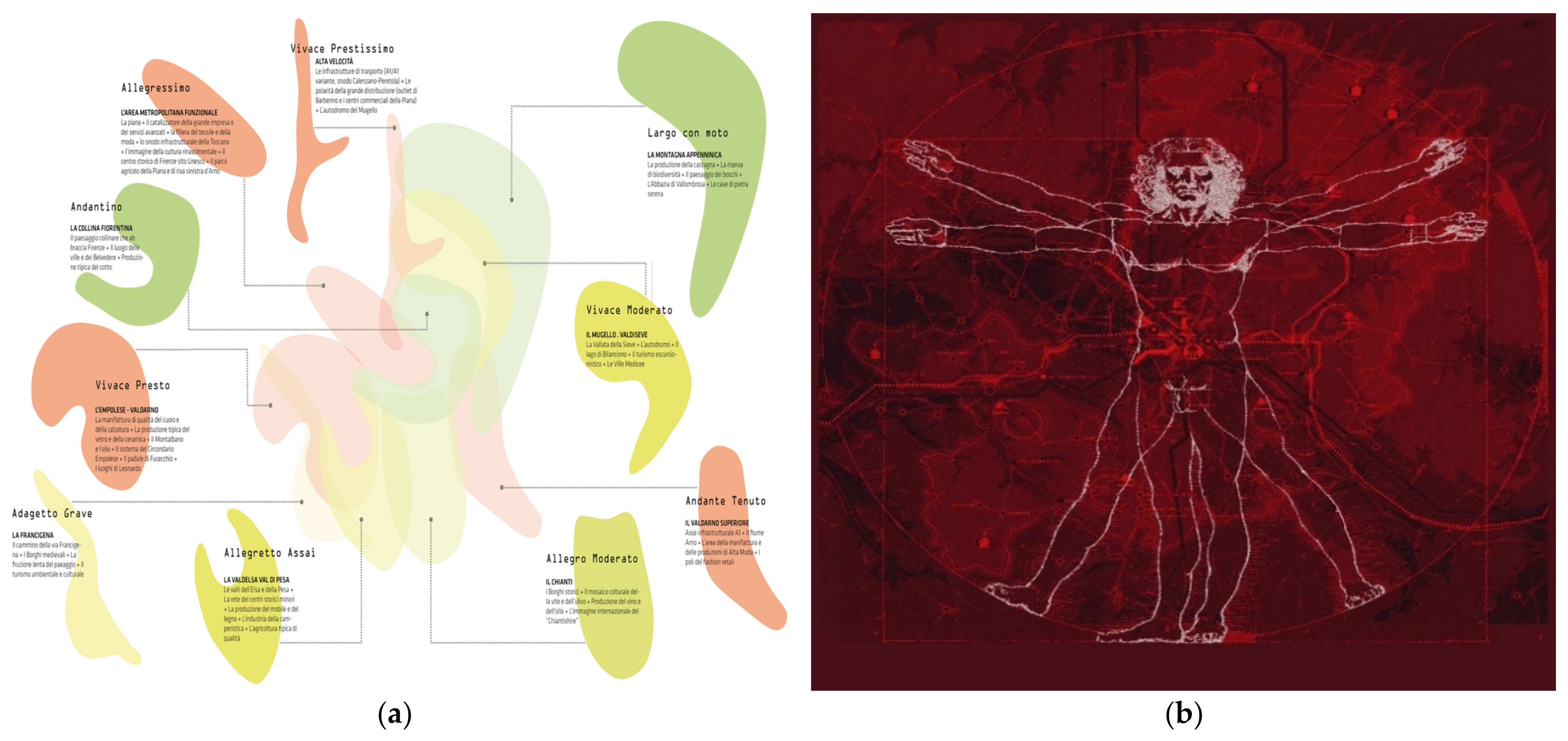

Macro and micro stories were represented together as “metropolitan rhythms” (

Figure 2a), a metaphorical spatial device adopted to visually translate the complexity of territories and their dynamics in current and future scenarios [

53,

57], and in three strategic visions of the plan (universal accessibility, widespread opportunities, lands of wellbeing) aiming to bring about a new ‘Metropolitan Renaissance’. This slogan evokes the image of a cultural rebirth of the Florentine territory, referring not only to the UNESCO site or to the core city, but to the entire metropolitan city.

The final mission was represented in both cartographic and metaphorical terms: the ideogrammatic map was defined by composing rhythms and strategies into a sole image of the future of Florence in 2030; the metaphorical device was the superimposition of the Vitruvian Man on the 100 × 100 km square territory of the metropolitan city, as if he were embracing it (

Figure 2b).

The strategic metropolitan plan was approved in 2017 by both the metropolitan council and the regional council as part of the Regional Development plan.

After that, the monitoring and updating process undertaken in 2018 by the MCF required mayors to make the vision their own. This is why in December 2018, together with the “traditional” presentation of the strategic plan in the metropolitan council with paper documents, a 4 × 4 m print of the vision was installed in the council room and mayors were invited to sign it and summarize the metropolitan territory identity in one word. This was spread widely on mayors’ and municipalities’ social media channels (

Figure 3).

5.3. The COVID Phase: Testing Institutionalised Imaginaries

After the Strategic Plan was approved, the MCF engaged with its monitoring and the definition of the Metropolitan Territorial Plan in order to apply the strategies to local contexts. These processes started in 2019 and came to a halt with the pandemic, which had very different impacts on the core urban area and the less urbanized areas within the metropolitan city of Florence.

During and after the 2020 lockdown, recognition of the need for a greener lifestyle emerged. Less populated areas, such as the Mugello mountains and Chiantishire, were identified as healthier places to live and to visit. Tourism flow was concentrated on these locations during the summers of 2020 and 2021.

The pandemic led to a social, economic and labour emergency and highlighted past attempts to combat over-tourism. It underlined the fragility of the tourism model developed over the years in terms of the city’s economy, especially in the city centre. In order to tackle this crisis, in September 2020 the charitable organization Fondazione Cassa Risparmio Firenze and the Intesa Sanpaolo banking group launched “Rinascimento Firenze” (Florence Renaissance), a 60 million euro socio-economic financing programme aimed at encouraging an ‘economic and social renaissance’ of typical Florentine small businesses. The financing, available through grants, was targeted at five key sectors for the metropolitan city: art and craftsmanship; tourism and culture; fashion and lifestyle; start-ups and technology and the agro-industry (

https://rinascimentofirenze.it/, accessed on 3 May 2022).

Moreover, the mayors of the municipalities in the first belt proposed the establishment of “Greater Florence”, a new institution to coordinate the urban and territorial policies of the capital city and the eight surrounding municipalities in the first belt. This proposal would enforce supra-local governance, but within shrinking boundaries concerning only the core and inner municipalities of the metropolitan city.

At the local level, the municipality of Florence launched “Rinasce Firenze” (Florence Rebirth), a project to collect ideas, through the active citizenship of Florence’s residents and stakeholders, on nine main issues: Polycentric City, A New Historic Centre, Green Spaces, Green Mobility, Economic Development, Culture, Families and Children, Welfare, Work and Homes, An Intelligent City (

https://www.comune.fi.it/rinascefirenze, accessed on 3 May 2022). Actions conceived for each issue defined and enhanced the actions of the PSM and, in some cases, represented an update of its strategies.

Finally, in response to the COVID-19 emergency, the enhanced EU cohesion recovery fund has allowed targeted interventions in some problematic areas, such as those related to social cohesion and unemployment. Within the framework of the National Operative Programme “Metro” (PON Metro), which targets metropolitan cities, certain projects in Florence were reviewed and implemented in 2020 to address the new problems: the strengthening of cycle mobility systems and new management of the housing problem [

59].

The post-COVID challenge for the metropolitan city is now to update the metropolitan strategic plan (which must occur under law 56/2014 every three years) by considering this moment as an opportunity to strengthen the vision of the “metropolitan renaissance”, which appeared to “resist” the pandemic shock. This can even be reinforced by evoking new and different ways of living and moving within a greener metropolitan city, where inner areas are “places of wellbeing” to escape to or live in.

Moreover, the concept of wellbeing has become an important international project at the University of Florence which, together with six other universities in Europe, has launched the “European University of Wellbeing-EUniWell” through which students can attend all the partner universities and acquire specific knowledge about wellbeing which, at the University of Florence, is connected to “Urbanity” (

https://www.euniwell.eu/, accessed on 3 May 2022).

6. Discussion: The Role of an RD Practice in Challenging Spatial Imaginaries

The strategic planning experiences developed in the metropolitan city region of Florence since the mid-20th century and the specific practice of regional design for the strategic plan of the MCF each had distinct purposes, strategies and approaches linked to different ideas of the metropolitan city and its extension.

Although almost none of the strategic plans and frameworks of the last century were institutionalised, the connected spatial imaginaries entered the collective imagination and became part of the regional plan in 1991 and the metropolitan strategic plan (PSM) which was approved in 2018. Moreover, the idea of “renaissance” represents a strong metaphor from the past to describe the future of the metropolitan city, and has been both confirmed and challenged by the pandemic.

In

Table 3, we describe the relationship between the RD process and the connected SI in light of the analytical framework proposed in

Section 3.

6.1. The Contribution of RD in Making Regional Imaginaries Visible

The case of the metropolitan city of Florence reveals a great mismatch between the institutional and functional metropolitan areas. On the one hand, the institutional boundary has been unable to seize on the socio-economic and functional trends that clearly emerged in the densely-populated settlements seamlessly joining the three cities of Florence, Prato and Pistoia. On the other hand, the institutional boundary includes municipalities from the northeast to the southwest, whose territories and settlements have strong historical roots and a perceived feeling of being “other” than part of a metropolitan city.

The imagination and construction of metropolitan regions changes across space and time. According to the different actors, spatial imaginaries evolve and change, and this process elicits strife among different conceptions [

60]. The difficulty faced by metropolitan citizens in recognizing themselves as such, especially those who live in peripheral areas of the metropolitan context who have developed strong and consolidated identities over time, is a clear indication of this trend.

These difficulties, which emerged during the participatory process, were tackled through a process of regional design aimed at making the “real” region visible and discussing its characteristics.

The transcalar design process considers the imaginaries of the metropolitan city at different levels: while macro-stories derive from statutory, traditional planning and programming, micro-stories relate to local and hyper-local projects, conceived as fundamental tactics to achieve the three strategic visions of the plan.

The metaphor of rhythms, as a synthesis of micro- and macro-stories, has been successful because it is easy to understand and because it implies the search for harmony between territorial areas with different identities, characteristics and dynamics of development [

61].

From a methodological perspective, metropolitan rhythms are the final result of a proactive reading of the territory, intended to join variable geometries from the “contradiction” of institutional reform, functional and socio-economic trends and perceived boundaries of the metropolitan city.

In this sense, the RD approach was able to overcome the spatial paradoxes of institutional reform by defining a shared representation of the metropolitan area in terms of its institutional and functional features.

One year after the approval of the plan, the path towards the appropriation of a metropolitan spatial imaginary in a broad sense still seemed far away. The working group attempted to identify ways of appropriating the vision with the metropolitan mayors. During the pandemic, the “shrinking” boundaries of the metropolitan city linked to its core and first ring of “greater Florence”. The contribution of the RD process lay in the identification of operational projects capable of implementing the strategies of the plan: emerging especially in relation to the dominant narratives of the debate about large-scale metropolitan projects (stadium, airport extension, new supra-local infrastructures for healthcare, technology farms). During the pandemic, increased attention was focused on the actions of the strategic plan concerning accessibility and slow mobility (bike paths within the city, trekking and slow tourism in countryside areas).

6.2. RD Provides for Insights: The Narratives of Greenery and Wellbeing

The strategic plans conceived at the end of the last century for the Florentine urban area were based on the visualization of the Florentine plain, understood as a system of urban and socio-economic development. After the Delrio reform of 2014, the shift of the reference axis from the functional to the institutional territory of the Province determined the need to visualize the metropolitan system of reference and to redefine the connected spatial imaginaries, in the context of the regional design process implemented for the metropolitan strategic plan.

Within the strategic planning process, the visualization of the territory’s characteristics highlighted the presence of an important system of mountains and hills with woods, vineyards and olive groves (Mugello and Chianti), representing more than 80% of the metropolitan area. This data, part of the analytical framework presented to the metropolitan council, provided insight into a “green” metropolitan city and was discussed several times in the context of the debate and in presentations of the plan given by the President of the Metropolitan City. The narrative of a “green” metropolitan city highlights the emergence of awareness of the opportunities generated by an agricultural territory and a hilly and mountain landscape of enormous value. While the non-urbanized territory was previously conceived as requiring the protection of superordinate bodies (the Ministry of Cultural Heritage through the superintendencies and the Tuscany Region through the Regional Landscape Plan), in the context of political discussion the agricultural or “green” territory was conceived as an “engine of development”. Incidentally, some areas of Chiantishire determine 20% of the metropolitan area’s GDP, through wine production and tourism. This first aspect has been discussed at great length, with the metaphor of rhythms permitting technicians and politicians to concentrate not so much on the conflict, but rather on the possibility of harmonizing positions taken by the advocates of conservation and those of development.

The visualization of territories with different rhythms of life provided strong insight into the coexistence within the metropolitan city of strongly urbanized territories (those on the plain, characterized by commuter movements) and “slow” territories. This latter group should not be understood as “lagging development territories” but as territories with a different rhythm of life, characterised by slowness and the fruition of special landscapes through sustainable mobility and development systems. The discussion following this insight led to the name of the third aspect of the plan’s vision being changed from “countryside as a development engine” to “lands of wellbeing”, with wellbeing understood as a life-style: it is true that in these areas services and urban transport are limited, but the presence of nature and the value of the landscapes increase the quality of life.

6.3. RD Institutionalises Shared Spatial Imaginaries: The Hold of SI during and after the Pandemic

Institutionalisation certainly has two implications: Regional design is expected to improve the process of the institutionalisation of current or new and future images of the metropolitan city in strategic planning documents and policies, and to lead or enhance the process of the appropriation of such. This means that images of the city’s future are expected to become part of the strategic planning documents and of the collective imaginary, entering into current narratives and discourses.

In the Florence case, institutionalisation of the images took place through the approval of the strategic plan by the metropolitan council: the metaphors of rhythms and the metropolitan renaissance are now an integral part of the planning document. In addition, the strategic metropolitan plan was approved as an annex to the Regional Development Program (RDP), the region′s programming document. This means that local administrations must prepare their own planning and programming tools and instruments in line with both the PSM and the RDP.

On the other hand, the reading of the process of appropriating the metaphors of the strategic plan and the images conveyed by the strategies in collective spatial imaginaries is more complex. The plan is based on simple strategies in which each name is defined in terms of its future characteristics by an adjective: accessibility is universal, opportunities are spread throughout the metropolitan area, which is also a land of wellbeing.

As for the mission of the plan, the theme of the “metropolitan renaissance” is certainly old wine in new bottles: for 500 years in Florence there has been talk of renaissance, and the Renaissance is the driving force behind the promotional policies of the Florentine area.

However, the decline in “metropolitan” terms is represented the true innovation of the RD path: the image of the Vitruvian Man who “spreads” himself over the metropolitan territory, combining the institutional territorial dimension with the historical identity dimension in a captivating metaphor, which has extended the propensity for rebirth. The idea of renaissance is not peculiar to the UNESCO site or the capital city, but has become an attitude of the entire metropolitan territory, as it was in the 14th century when the city and countryside were linked by mutual interdependence. This image of the Vitruvian Man, more than the cartographic one (see

Figure 2), has been diffused by the media, resulting in the repetition of the performance of the Renaissance theme in a contemporary key, extending to both the institutional and functional regional context.

After the approval of the strategic metropolitan plan, the spread of COVID-19 represented a great challenge for the imaginaries which were institutionalised within the strategic metropolitan plan.

The attempts to react to the pandemic’s momentum led, on the one hand, to the definition of new images of the metropolitan city, capable of breaking the inertia of territorial structures and imaging new and different futures for renaissance after the pandemic. The need for healthier and safer public spaces and mobilities led to the financing of bike paths and green policies within the framework of the recovery fund, giving rise to new narratives connected to a polycentric intelligent city with a new historic centre, green spaces, mobility, and new ways to conceive of the welfare, work and homes system through co-housing and co-living policies and projects, under the goal of a general rebirth.

On the other hand, the attempt at “rebirth” after the pandemic was rooted in the mission of the strategic plan: once again, the resonance of the “renaissance” concept appeared operative in terms of leading to tangible practices or projects [

16].

This narrative of a city that “resists” and rebirths, however, was mainly conceived by the capital city of Florence, while the need for distancing and greener spaces fuelled the conception of the metropolitan city as a “land of wellness”. A corresponding element was oversight regarding the effect of over-tourism in the city centre, which, after the pandemic, revealed the urgent need to implement PSM tourism strategies targeted at shifting tourist flows to the countryside and the Mugello mountains.

This vision of the metropolitan city as a harmonious system of “lands of wellbeing” was confirmed in the pandemic phase, not only with regards to tourism but also to citizens’ lives. The repetitive performance [

47] of the concept of wellbeing arose during the pandemic with increased awareness about the value of slowness and different rhythms inside the city, and of green and accessible territories in which the countryside, hills and mountains offer a safer and healthier setting just beyond the urbanized area.

Finally, the use of the term “renaissance” by the bank foundation to promote post-covid funding, as well as the use of the term “wellbeing” for setting up a European University, are evidence of the power of these metaphors to “travel” at different scales (from the metropolitan to the local and back), and among diverse institutions.

7. Conclusions and Directions for Further Research

Regional design as an imaginative and creative planning practice is expected to improve the quality of spatial planning strategies and governance settings, by capturing existing images of the region and providing visions of its future.

While there are great expectations about its power to “change the actor’s mind”, the evaluation of its performance in relation to spatial imaginaries has not yet found empirical evidence. The presented research helps to fill this gap by providing a theoretical framework for analysing the impact of regional design on spatial imaginaries, in terms of its capacity to grasp them and even to change them. With reference to the debate on the performativity of spatial imaginaries, and to the performance of regional design, we propose evaluating the performativity of regional design in grasping and eventually changing spatial imaginaries. This evaluation will be achieved by analysing RD’s capacity to make the region visible, providing moments of insight and institutionalising certain imageries through processes of SI resonance.

Under the lens of this analytical framework, the metropolitan city of Florence provides useful understandings of spatial imaginaries that have concerned the city-region over time: in particular, since the second half of the 20th century, the attempt to develop a scheme for the metropolitan area referring to the functional area and its connected spatial imaginaries, even if these have not been institutionalised, has shaped local and regional planning practices.

In 2014, the institutionalisation of the metropolitan city on the boundaries of the previous province challenged the spatial imaginaries of the urban region and led to the activation of a Regional design process to join the functional, perceived and institutional dimension of the region in a shared region. Finally, the spread of COVID-19 has represented a great challenge for the strategic metropolitan plan: attempts to react to the pandemic’s momentum have lead, on the one hand, to the definition of new images of the metropolitan city, capable of breaking the inertia of territorial structures and imagining new and different futures for the renaissance after the pandemic. On the other hand, the attempt to “rebirth” from the pandemic was rooted in the strategic plan’s visions, which “resist” and fuel the need to conceive of the metropolitan city as a “land of wellbeing”.

Although the final version of the strategic plan was approved in 2018, it is impossible to define the long-term performance of the regional design approach; however, the challenges brought about by the pandemic have been seen as a moment to evaluate the performance of both the RD process and its design product, the strategic plan. In this sense, the COVID-19 pandemic represents a sort of litmus test for measuring the strength and resistance of spatial imaginaries conceived within previous strategic planning and regional design processes, especially with respect to the 3rd issue of the analytical framework.

In this sense, even if the research results are built on a single case study in a specific context, they shows to be consistent with previous theoretical studies of both the performance of RD and the performativity of SI, and the issues at stake are suitable for generalisation.

In general terms, the analytical framework provided a useful grid for reading the performance of regional design in enhancing spatial imaginaries and, in the light of the case study, a generalisation can also provide useful directions for future research directions concerning the reading of the interrelations between RD and SI in relation to different contexts and time periods.

First, the process of framing the region and visualizing its possible future development through an RD approach is intended to define the region not only in terms of physical interventions but also by helping to create institutional and organizational capacity [

14,

46] through representations of the connected spatial imaginaries of the current situation and future scenarios.

The Regional design process embarked on by the metropolitan city of Florence has helped to make the region visible and to enhance the vision for its future. A vision based on consolidated spatial imaginaries of renaissance and that has been challenged, but not overcome, by the pandemic.

However, the results of the case study analysis highlight a contraction of the spatial dimension of imaginaries of the region due to the occurring pandemic. Such challenges led to broader reflections on the performative value of Regional Design in grasping and challenging the spatial imaginaries of everyday life, which have been greatly challenged by the pandemic. The process of planning daily actions is connected to the spatial imaginaries of the region people live in, and refers to life and experiences rather than administrative and functional boundaries. This micro dimension clearly emerged during the pandemic and led to the definition of the 15-min city [

62].

While the architecture of the strategic plan for the metropolitan city of Florence, through a Regional Design approach, was conceived to coordinate micro-stories into general strategies, in the post-pandemic phase this approach calls for an extension of such practices. Spatial planning has the renewed task of coordinating these micro activities and their connected polycentric space systems in a macro vision. Moreover, a series of questions emerge about the need to define a strategic vision by referring to spatial imaginaries at micro level: how have images of the region changed (both in terms of spatial imaginaries, as well as cartographic/metaphorical and narrative representations) with the change in scales and geographies of reference conveyed by the pandemic? How do post-pandemic spatial imaginaries influence the modelling process of urban regions?

Secondly, Regional Design has provided insights into the real nature of the region, even leading to a change of mind concerning its possible future, not only connected to made-in-Italy and tourism in the capital city, but to the quality of life and landscape around the city.

The reading of the “evolution” or “involution” of competing and evolving spatial imaginaries, indeed, can open up interesting perspectives on the analysis of the role that RD plays within processes of future-building, by visualising and even creating spatial imaginaries that differ and evolve over time, gaining or losing attractiveness but, in general terms, setting a new direction for the government’s investments and policies.

Under this direction, an RD approach can answer to Davoudi & Brook’s claim for enhancing transformative imagination: “While making the invisible visible is a necessary step, it is not enough for disrupting taken-for-granted imaginaries and offering effective alternatives. For that, planners and other stakeholders need to recognize and mobilise the power of transformative imagination which, as Castoriadis (1987, p. 81) put it, is ‘the capacity to see in a thing what it is not, to see it other than it is.’ ” [

41] (p. 58). In this sense, indeed, RD can be seen as a method for future literacy, as it provides insights on different, disruptive and even unthinkable futures [

62]. Finally, the concept of resonance [

15] has showed to be consistent in tracing the “hold” to coronavirus of spatial imaginaries defined and even institutionalised through regional design processes held before the pandemic.

However, this research only takes into account changes in spatial imaginaries that occurred in traditional spatial representations (maps, cartographies and policy documents) of the metropolitan city within the PSM and regional planning documents, as well as narratives emerging from interviews and the analysis of (online) questionnaires. It does not take into account the explosion of images, both in terms of visualization and visioning practices, that has developed in the digital era and grew exponentially during the coronavirus lockdown: images of empty cities spread all over the world, together with images of the “lost” spaces of the heart, referring to a growing multiplication of spatial imaginaries.

What further research should identify is the acceleration of changes in spatial imaginaries within and after the pandemic shock: as individual representations, SI travel now at a speed that was previously unthinkable, and they can suddenly become viral as shared collective representations of spaces and places.

This acceleration of the process of creation (and destruction) of spatial imaginaries, due to the exponential use of online devices and networks, seems to be promising for forward in-depth research concerning their exposition to the dynamism of the digital era [

3]. In particular, this affects the institutionalisation of spatial imaginaries, which is now challenged by this explosion of dynamism. If, in order to gain traction, spatial imaginaries need to compete with previous and parallel imaginaries, including those of territorial government (planning at all institutional levels) and/or other soft spaces originating from other stakeholder partnerships and agreements [

14,

15,

63], their exposure to multiple competing spatial imaginaries, found on global networks, submits them to the risk of great turnover.

On the one hand, this calls for further research on SI to highlight this trend, through methodical, reasoned empirical research on how different and competing spatial imaginaries, related to multiple-and now also virtual-sites and scales, create momentum by being institutionalised and translated into tangible strategies, practices or projects that last over time and concern territorial identities. On the other hand, Regional Design practices need to tackle such a turnover, by taking into consideration both consolidated and new emerging spatial imaginaries in the definition of actual and future visions of a region.