1. Introduction

Daena J. Goldsmith put forward the view that the analysis of social support may be the source of both known and unknown aspects related to the means whereby discussions about existential issues can help people overcome life challenges [

1]. We find this idea a pertinent way to start discussing the concept of social support, since it relates to a social phenomenon that manifests itself as a way of dealing with the personal problems generated by everyday experiences; a phenomenon whose intensity of manifestation turns these problems into matters of constant concern. Everyday experiences can be shaped by a local, regional, national or European socio-economic reality. These issues arise from the relationship individuals establish with their social environment. The idea of social support does not refer only to solving personal problems but also to sharing them with the members of the social network to which each person belongs at a given time. Moreover, social support as a phenomenon is also manifested as a form of solidarity, which occurs not only at the request of the person who feels the need to share a personal issue, but also appears, quite often, as a manifestation of anticipation on the part of the supporter. Social solidarity is a complex phenomenon with profound implications for the homogeneity of a human community. Social homogeneity is the great stake of the construction of the global social space. Starting from the aforementioned reasons, our study argues that the development of sustainable strategies for building a European society must take into account the forms of manifestation of social support, which generate solidarity between people and ensure the cohesion of groups.

Social support is a factor that leads to solidarity and contributes to the satisfaction of relationships developed in couples. During stress-dominated periods, it prevents emotional breakdown or depression and combats the increase of intensity in conflicts by strengthening the bonds between partners [

2]. Perceived social support refers to the degree of support that individuals feel as coming from significant others. Friends, family-members, colleagues, or other representative individuals may be sources of support [

3]. The role of social support is that of stimulating the achievement of individual goals. High social support is associated, through causal links, not only with physical and mental health, but also with psychological resilience, self-esteem and subjective well-being [

4]. However, some studies have shown that social support can undermine the pursuit of goals. Certain experiments have revealed that participants with an abstract perspective on social support demonstrated greater determination and worked harder so as to achieve their goals, compared with participants who had a concrete representation of social support. [

5]. The perception of high social support leads to a lower risk of drug use and reduced risk of mental dysfunction or serious health problems, while at the same time limiting involvement with forms of unsafe sexual behaviour. Social support has a positive impact upon well-being, both at the individual and collective levels. Perception of social support may alleviate addictive behaviours with harmful health consequences. The consistent perception of social support may contribute to the development of the three components of happiness (positive affect, absence of negative affect and satisfaction with life as a whole) [

6,

7]. Other examples of how social support impacts on people’s daily lives may be provided, although the aspects illustrated so far clearly illustrate the positive influence of social support upon society. From this perspective, it may be pointed out that social support is a ubiquitous phenomenon, necessary in the life of each individual, which, when manifested with great intensity, has beneficial effects in the evolution of everyday experiences. As regards social homogeneity, two aspects relating to social support emerge as essential: On the one hand the absolute generality of the phenomenon (social support is manifested in all people) and on the other hand its quality of being desirable (due to its beneficial effects, social support is desired by all). Any social phenomenon that brings together and sums up the two aforementioned qualities is regarded as a strong factor that contributes to the implementation and commitment to behavioural patterns in society. Such social phenomena ensure cohesion and contribute to the shaping of society.

The social structure of the European Union has always been a sensitive issue, which, if not properly monitored and organized, may become a serious obstacle to the construction of the European Community space. We therefore argue that social support should be used as a form of defining European identity in the particular case of each citizen. Our study provides a comprehensive description of social support based on information gathered from a sample of 1346 European Union citizens living in north-western Romania. The Romanian sample is sufficient for the studied problem because social support is neither a regional, nor a cultural phenomenon. At the same time, it does not have specific characteristics that depend on individuals’ nationality. We analyse a desirable phenomenon with a high degree of generality, and thus the data provided can apply to any social context.

From the perspective of European studies, the process of building a strong Europe is based on inclusion and equity. The objectives and instruments of the cohesion policy, combined with the various aspects that influence the daily life of each European citizen, generate effects that influence the formation of European social structures. In the opinion of sociologists and social psychologists, social cohesion can be interpreted in terms of either the presence or the absence of social obligations [

8]. People’s social obligations generate emotions of different types and intensities, which are shaped by personality traits, education, age and other individual attributes. However, social obligations provide some predictability in relation to everyday actions and condition the individual from the perspective of social integration. Social support is often needed when there is a sense of inability to meet social obligations in a form accepted by the community. Therefore, there is a close and deep relationship between social support and social cohesion. The analysis of social cohesion focuses on measuring indicators such as solidarity, reciprocity, trust, equity or social inclusion [

9]. As these indicators have a largely subjective dimension, it is difficult to measure the phenomenon. In addition, due to social dynamics, which generates frequent changes in people’s moods, the data gathered are perishable. On the other hand, the concept of social support is a much more stable one, as long as it relates to moments of personal history. Based on events that have or have not happened, it can be assessed whether or not a person or an institution has offered support in fulfilling social obligations.

Other studies emphasize social cohesion as a phenomenon resulting from interactions among groups, social unity being a result of such interactions [

8,

10]. A context with strong implications at the level of group interactions is the educational context, where institutions fulfil the role of organizing activities and implementing skills at the level of school groups (classes, groups of students). Institutional education is complemented by the phenomenon of self-education, which often involves social support. The help provided by others is also necessary. The purpose of self-education is to increase independence from the institutional systems, which demands both time and expenses. This independence ensures a personal comfort, whose strength is influenced by the intensity of the social support provided [

11,

12,

13]. In such a perspective, the subjective availabilities of individuals no longer actually belong to them. Solidarity, trust, and reciprocity are forms of covering social obligations. Group membership is a compelling force that makes individuals act in specific ways. The two theoretical perspectives are not always consistent with each other and sometimes even imply contradictory elements. The introduction of social support as an alternative to understanding the forms in which social cohesion manifests appears a desirable alternative.

When we set out to analyse social support, we started from the desire to offer a practical applicability to this research approach. We wanted to answer the questions: why study social support? What will be the benefits and how can the explanatory model of social support used? In this context we understand the link with the phenomenon of social cohesion and the European community. In fact, this relational context shaped the interpretation of social support. The European Commission’s Eurobarometers show that the most common factor in motivating public opinion about the membership of Eastern European states in the structure of the European Union is to increase the quality of life. Our study defines social support as a determinant of living standards, social cohesion and community integration. Furthermore, social cohesion is a phenomenon of great interest in the context of building a homogeneous European Union society. In our study we constructed a model for interpreting social support that could be used as a barometer of social integration of local, regional or even national communities in the global social system, promoted by the European Union. The proposed model of social support interpretation can highlight features that stimulate or, on the contrary, obstruct cohesion between a community and the social space of the European Union. In this way we want to offer an accurate method of analysing and interpreting the cohesion between a European community and the social ensemble of the European Union. In fact, the originality and scientific contribution of this study can be summed up in the development of interpreting social support method, that explains the degree of cohesion between different communities of the European Union.

Evidence from Studies

The main purpose of this study is to highlight the forms in which social support can be perceived and associate these with the formation of the European Union’s social structures. Our approach intends to point at some general needs that relate, on the one hand, to citizen’s motivations to be considered European citizens and, on the other hand, to their aim of contributing actively to strengthening the social space of the European Union.

People’s daily concerns are largely focused on meeting their personal or family needs and coping with the problems that occur daily. The objectives of perpetuating a European social space can be achieved as long as this social space is regarded by its citizens as an environment where their needs can be fulfilled and where solutions to difficulties associated with life events may be found. Below, we shall present some studies, carried out at the European level, which emphasize both the way social support is perceived and its relationship to life events or life satisfaction. The selected quantitative studies, which were conducted during the last two decades, are presented in

Table 1. The search was based on keywords from international databases such as ProQuest, EBSCO, PsychInfo, PubMed, Scopus, Sage, SringerLink, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. Quantitative studies were classified based on the scales used to measure perceived social support, but also in relation to the type of the study (e.g., experimental, cross-sectional, or longitudinal). In order to avoid redundancy, we decided to discuss the conclusions based on studies that were considered relevant.

Knoll and Schwarzer [

14] have demonstrated that women who reported the highest social support also had a low level of negative mood and thus a better state of health compared to men. In addition, young women reported to have benefited from more social support compared to middle-aged or older women. In the case of men, regardless of the participants’ age, the reported level of social support was the same. Schulz and Schwarzer [

15] evinced that, in the case of patients diagnosed with cancer, the support provided by a partner had a positive impact both on patients’ well-being and on their ability to cope with the disease while patients who benefited only from limited social support encountered more difficulties. Marian [

16] did not identify gender differences in measuring the perception of social support; however, in a study aimed at validating the scale of perceived social support, the researcher indicated that the instrument had discriminatory capacity, depending on patient categories. Other studies have shown that social support from the family seemed to decrease with the age of the respondents [

17,

18]; along with this limitation of support, there was an increase in the number of declared cases of depression.

In patients with chronic stroke, Adriaansen et al. [

19] found that, although patients benefited from social support for a while, it tended to decline over time. Social support was positively associated with life satisfaction regardless of the concerns expressed by partners.

Alexe et al. [

20] found that, in the case of performance athletes, perceived social support was not associated with the frequency and severity of daily hassles or negative life events. On the other hand, Marian et al. [

21] have argued that the orientation towards reconciliation in organizations was more common among employees with high social support while the orientation towards revenge at work was more common among employees with low social support. On the other hand, perceived social support appeared to act as a buffer between the offense perceived by employees and the negative emotions that generated revenge in organizations. However, Mekeres et al. [

22] have shown that perceived social support was not associated with the internalization and appreciation of scar size by post-traumatic and post-surgical patients. Comparison of batches including patients having gone through surgical interventions versus groups suffering from post-traumatic conditions did not indicate differences in the perception of social support coming from family, friends and significant others due to the availability and allocation of psychological resources.

In a study focusing on Slovak teenagers, Lichner et al. [

23] showed that loneliness could be multifactorial in nature; negative correlations were registered with the perception of significant others.

Based on the examples presented above, we may conclude that social support influences not only mood or one’s closeness or remoteness from others but works in different ways at the inter-human lever. It also functions differently in particular geographical regions.

We consider that little attention has been paid to the absence or presence of circumstances in which both the perception of social support and the hypothetical adaptive consequences occurred. Previously published studies did not identify (hypothetical) mechanisms that influenced social support in a representative community, with effects on the functioning of that society, focusing instead on specific and sectoral issues. A better understanding of these circumstances in the communities of the European Union is essential in relation to decisions aimed at improving cohesion policies. As regards the collective perception of EU citizens, the appreciation of the European social space as a social structure that determines and encourages the support from others in the context of life events might be an advantage. This will increase the community citizens’ motivation and desire to be part of the social structure of the European Union.

Table 1.

European measurements of social support, the stressors studied, and their effects.

Table 1.

European measurements of social support, the stressors studied, and their effects.

| Study | Social Support Measures | Method | Stress/Strain/Distress | Effect |

|---|

| Knoll & Schwarzer [14] | Self-constructed 11-item scale | Longitudinal; Self-report questionnaire | Depression, anxiety, and Health Complaints | Positive main effect |

| Schulz & Schwarzer [15] | Self-response: The Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS) | Longitudinal; Self-report questionnaire | Cancer | Positive main effect |

| Marian [16] | Self-response: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaire; Factor analysis | General population | Positive main effect |

| Vollmann, Antoniw, Hartung, & Renner [17] | Self-response: Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) | Longitudinal; Self-report questionnaire | Couples | Mixed effects |

| Adriaansen, van Leeuwen, Visser-Meily, van den Bos, & Post [19] | Self-response: Social Support List (SSL-12) | Prospective cohort study; Longitudinal; Self-report questionnaire | Patients with stroke and their spouses | Positive main effect |

| Melchiorre, Chiatti, Lamura, Torres-Gonzales, Stankunas, Lindert et al. [18] | Interviews/self-response: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaire; interviews | Old age | Positive main effect |

| Marian, Barth, & Oprea [21] | Self-response: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaire; Path analysis | Employees/organizations | Mixed effects |

| Alexe, Sandovici, Robu, Burgueño, Tohănean, Larion, & Alexe [20] | Self-response: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaire; confirmatory factor analysis | Athletes | Positive main effect |

| Lichner, Žiaková, & Ditommaso [23] | Self-response: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaire | Adolescents | Mixed effects |

| Mekeres, Voiţă-Mekereş, Tudoran, Buhaş, Tudoran, Racoviţă, Voiţă, Pop, & Marian [22] | Self-response: Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Cross-sectional; Self-report questionnaire; confirmatory factor analysis | Post-traumatic scars | No effect |

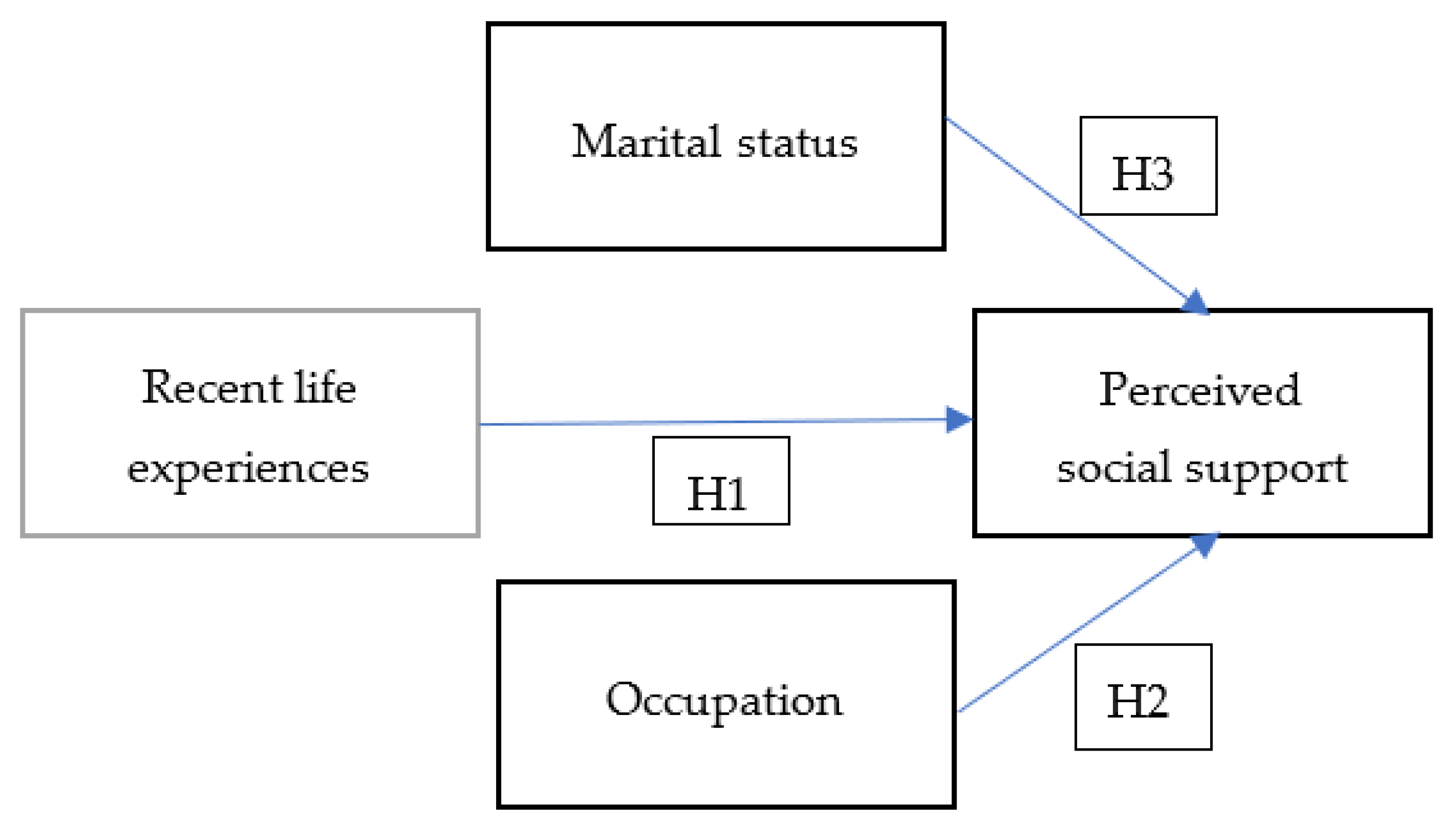

5. Discussion

The variables included in the study met the general goodness of fit indexes in accordance with the recommendations of the literature on SEM models [

38,

39]. In terms of our conceptualization, the behaviour of people in the North-West area of Romania can be explained by the direct and the indirect effects of life-threatening events, occupation and marital status on social support. First of all, everyday life events (through time pressure, work difficulties, financial worries, social and cultural difficulties) directly indicate a pressure on social support. Respondents reported that a higher number of recent life events (sometimes exceeding the barrier of personal tolerance) limited their perception of the support provided by family, friends or the significant others. Our results show that respondents participated to a lesser extent in prosocial activities that ensured and promoted socially sustainable forms of behaviour. The study is consistent with other interdisciplinary analyses focused on social support [

20,

23,

43,

44].

However, not all recent life events can be considered negative and directly related to well-being. Therefore, daily difficulties, social support and coping style are significantly interconnected. In terms of social support, increased values associated by the respondents in the North-West area of Romania with daily hassles could be correlated with lower levels of satisfaction with social support, for which respondents demonstrated a biased perception. We consider that, generally, daily problems are inversely related to satisfaction with perceived social support, as emphasized in

Table 5 and

Figure 2.

5.1. The Negative Aspects of Social Relationships

The benefits of interpersonal relationships for people who live in stressful circumstances do not help in avoiding the potentially problematic aspects of individuals’ relations with other people or the uncertain effects of their attempt to gain support. It is therefore imperative that both positive and negative aspects of social involvement be taken into account. We find that the perception of social support has an indirect influence, being related to the way occupational status has an impact on life satisfaction and ultimately on well-being.

What happens when people facing troubles and stress increase their efforts to gain social support? Seeking explicit support can be an inefficient means of coping with the environment and an equally unsustainable one, especially for people with a low level of education and those included in the old-age category. This finding could be a reflection of the circumstances in which social support is not obtained easily, so that people have to resort to other problem-solving strategies [

1,

2,

3,

7,

16,

17]. In addition, people’s efforts to increase social involvement and get support expose these individuals to socio-economic demands that they cannot meet.

It is possible that the occupation (COR), which is a precedent and a causal factor in the perception of social support, is in fact the result of such a conflicting connection. For example, some employees may increase their level of involvement in the profession as a result of low perceptions of family support and as a consequence of loneliness [

21,

45]. At the same time, it appears that many of the relationships observed in this study are potentially bi-directional. We consider that the situation presented above, although valid in the relationship between occupational categories (COR) and social support may also be valid in the relationship between occupational categories (COR) and life satisfaction [

46,

47]. We emphasize that the possibility of non-recursion or bi-directionality could be extended to all relationships between social support and relevant factors. Consequently, we credit Hoyle’s [

39] statement that “directionality is a form of association distinguished from non-directional association either by logic (e.g., income cannot cause biological sex), theory (e.g., group cohesion effects group performance), or, most powerfully, by research design (e.g., a manipulated variable to which subjects are assigned randomly cannot be caused by a dependent variable)” (p. 10).The SEM model presented in this study cannot unequivocally select the most correct direction of relationships.

Employed respondents generally have an extensive social network and receive more social support compared to pensioners and the unemployed. Occupation improves life satisfaction and facilitates social integration, so well-being [

33,

34,

35] is not majorly affected by daily hassles [

29,

30,

31].

5.2. Marital Status, Daily Hassles, and Support

Marital status is often accepted as an indicator of social support [

2,

48]. There are some difficulties in making global comparisons between married and unmarried people, which have not been sufficiently debated in the literature. In our study, low marital status values reflected (a) isolation, (b) the effects of widowhood, separation or divorce, or (c) low quality relationships. However, for married people, high scores probably reflect the respondents’ involvement in a relationship, which is a source of self-satisfaction and mitigates the impact of daily hassles. On the other hand, lifelong transitions may indicate that the lack of a confidant outside of marriage may be associated with psychological stress. Thus, it seems that the key factor in accounting for the positive effects of perceived support is a satisfactory couple relationship. The possibility that the support perceived may be ensured by other sources has significant theoretical and practical implications. However, there seem to be circumstances in which the husband is not necessarily a part of the social framework in which daily hassles take place, such as the case of stress at work, time pressure, social rejection, etc.

The dimensions of social support affect well-being differently [

33,

35,

36]. Our findings provide insight into the relationship between social support and marital status by identifying potential targets for psychosocial interventions that promote mental health.

The functional social network being associated with marital status will lead to health benefits, including low morbidity and mortality [

48,

49,

50,

51]. An important objective of the study was to investigate the influence of marital status on social support, but also the connection between marital status and recent life events in respondents in the North-West region of Romania.

The coefficients obtained during the study indicate that being married in itself is not a universal benefit; instead, the satisfaction and support associated with a marital relationship is important. The marital relationship had a distinctive role in our study because the results show that the support from the social network does not compensate for the effect of loneliness and perceptive distortions identified in the case of divorcees and widows. These results highlight the complexity of the influence of the status of relationships on both the medium and long terms and emphasize the role played in mitigating the effect of life events that can generate distress with direct action on the body, psyche and society.

6. Conclusions

Over the last two decades, there has been an increase in the number of studies that do not clarify the methodological orientation towards the perceived social support or towards the support offered and/or the support received. Therefore, the implemented research nuanced the theoretical and experimental orientation towards the perceived support of people from a border region of the European Union.

The analysis of perceptions on social support allows us to draw some strong conclusions about the role played by this phenomenon in maintaining social structures. A strong society is characterized by social structures and sustainable collective values. Our study shows that, where the phenomenon of social support is perceived and manifested in people’s lives with high intensity, social cohesion is high and the social environment is stable. The analyses carried out emphasized how the understanding of the different aspects related to the perceived social support illustrates the determining relationship between this phenomenon and the social cohesion.

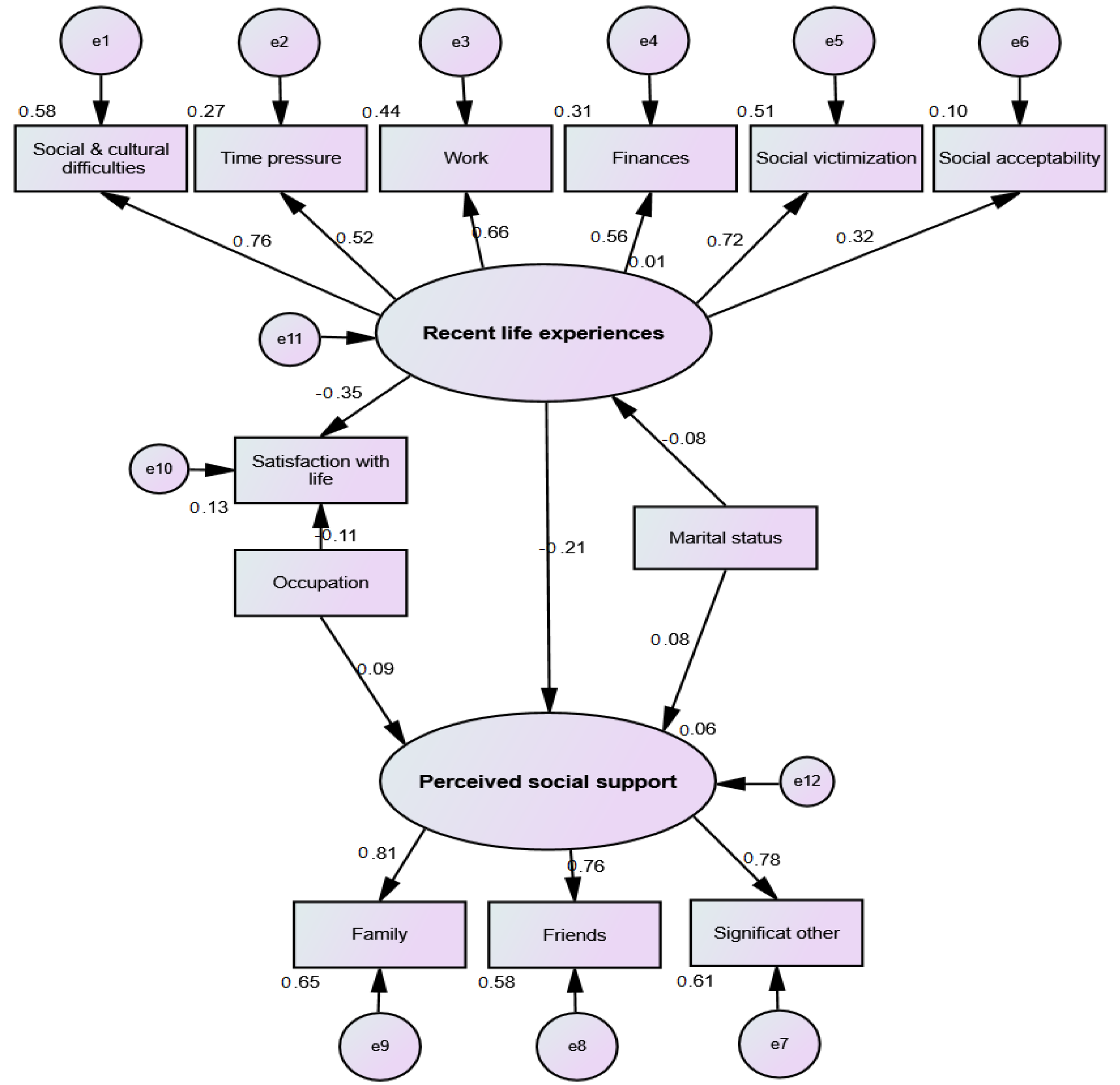

Structural equation modelling (

Figure 2) demonstrates the major importance of social support in people’s lives. Recent life experiences and the essential factors that describe them are constant and assiduous preoccupations in people’s daily lives. These factors indicate the level of social integration and therefore the level of success in life. The determining relationship between social support and recent life experiences is mathematically demonstrated in SEM. At the same time, according to the model, the forms in which this permanent relationship is manifested imply a satisfaction with life at the individual level. A comparison of the different population groups shows a homogeneous perspective of the perception on social support in the case of gender relations. The question that has arisen is why both men and women express themselves almost similarly in their perception of social support? Our conclusion is that this situation is another form that confirms the importance of social support in everyday life. Thus, social support is a permanent concern, a continuous need for existence, regardless of gender. As in the case of physiological needs (food, clothing, heat), social support is manifested in both genders, and represents a basic need in the pyramid of social needs. In other words, the homogeneity of manifestation is due to the general conditioning elements related to the objective of social integration, but also to the permanent character in the development of daily activities.

Moreover, the analysis of the SEM model (

Figure 2) statistically demonstrates that social support is at the core of social integration factors. As a universal goal, social support is one of the most important factors in social cohesion. This aspect is reinforced by the permanent manifestation of the phenomenon. Everyday life and people’s relationship with others is characterized by a permanent need for social support. The analysis model proposed in our study highlights social groups according to the perception of the phenomenon. Thus, the groups that perceive a high or low social support may be identified. This is valuable information that guides intervention strategies aimed at increasing and maintaining social cohesion. It has been found that people over the age of 46 tend to perceive low social support. The same happens in the case of people with a low level of education (respondents with secondary education), in the case of those with marital status as widows or divorced, in the case of those living in rural areas or in the case of respondents belonging to certain occupational groups (G6—agricultural, forestry and fishery workers). Statistical analyses demonstrated that these socio-demographic characteristics show a significant correlational relationship with the phenomenon social support perception.

The SEM model (

Figure 2) includes the most important aspects of life that are decisive in the process of social integration (social relations, occupation, job, marital status, time pressure, life satisfaction, etc.). Perceptions of the possibilities of social integration that lead to positive feelings about life satisfaction are the most motivating phenomena that determine individual actions aimed at ensuring social cohesion. These interpretive models provide concrete guidelines for understanding and intervening with the aim of strengthening social cohesion.

We consider that the development of the global society and the huge interests that the European Union has for the social strengthening of the community space, represent contexts that highlight the scientific approach of this study.

Speaking about the limitation of the proposed study, we do not have a method for the numerical interpretation of the personal degree of social integration. This would allow us to validate the method of social cohesion, analysed through the formula of interpreting social support, that is promoted and applied in this study. Thus, we could have measured the level at which social support determines the cohesion between different communities of the European Union.