1. Introduction

The concept of national security is quite broad and encompasses the diverse perspectives of scholars. National security is often interpreted as a multifaceted systemic construct covering many variables or areas of activity. It must, admittedly, be noted that with the development of the concept of national security, security was mostly measured in terms of military power and capabilities. This concept is broadly in line with the traditional (realism) approach [

1]. However, over time, the concept of national security content has expanded. Buzan [

2] attempted to broaden the scope of security, stating that security studies should not be limited to the military aspect, and proposed five aspects of security: military, environmental, economic, political, and societal [

2]. Holmes [

3] uses the concept of nonmilitary national security and has expanded the list of key security areas to include areas such as political security, economic security, energy and natural resources security, homeland security, cybersecurity, human security, and environmental security. Such a holistic conception of national security was supported by Chandra and Bhonsle [

4], who stated that there is no area of public life that would not affect national security. Therefore, no single area of socio-economic life can be considered hierarchically as a determinant of national security. The concept of national security is inseparable from individual security. Buzan [

2] states that the essence of individual security lies in the context of the links and contradictions between personal security and state security. The state is the main source of public security. Individual security is often associated with economic security, which is one of the key components of national security. It should be noted that security at the individual level is further subdivided into objective and subjective security, which can be measured by objective and subjective indicators, respectively. However, these concepts are not very clearly defined in the scientific context. According to Nussbaum and Sen [

5], objective security refers to reports of factual conditions and overt behavior, whereas subjective security stands for measurement of attitudes. In the field of security research, these concepts are perceived as: objective security means being safe and subjective security means feeling safe [

2,

6]. However, the image formed in the public consciousness does not always coincide with the real, objective situation. It should be noted that economic security of the individual, which is often associated with income [

7,

8], can also be perceived through the prism of subjectivity [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Citizens are at the center of national security strategies, but little is known about the interrelation between any individual’s objective and subjective financial well-being and his/her perception of national security. This paper presents a unique examination of public perceptions of national security based on personal income as a key factor in economic security. Thus, the study examines how an individual in a society evaluates his/her individual and national security from the individual’s objective and subjective perspectives.

The aim of the research is to explore the interrelation of personal income with the perception of national security in the Baltic states, namely Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. A low level of income of an individual limits his/her consumption, which can have negative consequences, including lack of opportunities to participate in public life, social exclusion, and sometimes existential problems [

13]. Low income levels, poverty, and social exclusion are among the most critical areas in the Baltics. These areas are inseparable from national security. Unresolved social problems can, in the long run, transform into riots, conflicts that endanger the well-being, health, and lives of members of a society. Therefore, the economic security of the individual, which is often assessed through the prism of income, is closely linked to national security. There is a lack of research in the scientific context to assess the links between an individual’s income and the perception of national security.

The investigation includes the following sections: literature review, methodological approach, research results and discussion, and, finally, conclusions.

3. Methodological Approach

In the empirical research, the following

hypothesis is formulated: both objective and subjective living conditions, represented by personal income, are significant determinants influencing sense of national security among the population. At the same time, objective living conditions (personal income) is a more important determinant for the sense of national security than subjective living conditions. Aiming to test the hypothesis and to identify exact determinants influencing the sense of national security in the population, a representative quantitative survey in three Baltic countries—Estonia (further in text—EE), Lithuania (further in text—LT), and Latvia (further in text—LV) was conducted in August 2021. The fieldwork was carried out by the public opinion and market research company Baltic Surveys. The general population considered in the sampling differ in the countries was: in Estonia—habitants 15 years old and above, in Lithuania and Latvia—18 years old and above. Nevertheless, the

sampling method in all three countries was the same—the probability multi-stage structural method [

54], based on criteria of geographical region, size of settlement, gender, and age. This way, in Estonia, 1003 respondents, in Lithuania, 1006 respondents, and, in Latvia, 1017 respondents were questioned. After some manipulations with the variables necessary for the international comparative analysis, as well for optimization of analysis and interpretation of the results, one database with 3026 cases in total was created and explored. For correction of the empirical data in accordance to the initial representative sample in each country, weights were applied in all calculations.

The research instrument consists of eight main questions and, additionally, questions on socio-demographic characteristics. Among the former, the first question concerns perception of national security and is formulated in the form of statement: “I feel safe living in my own country.” With the 5-point scale, 1 = totally disagree and 5 = totally agree.

The next six questions concern subjective living conditions, represented by perception of personal income. These questions are also formulated in the form of statements, and the respondents are asked to evaluate them with the above-mentioned 5-point scale. The statements are the following:

- (a)

I am happy with my current income.

- (b)

My current income allows me to purchase food and other necessities without worrying too much about expenses.

- (c)

I have no financial difficulties in paying utilities, rent, bank loans, leasing, and other liabilities.

- (d)

I can spend money on leisure, travel, entertainment, and development.

- (e)

My current income allows me to set aside part of my income for savings.

- (f)

I can afford to help other people asking for financial help.

For the identification of objective living conditions, one question is formulated on income per household (further in the text—HH) member per month. Because of the sensitivity of the question, the respondents were asked to mark an interval into which income of their HH falls. In the standard questionnaires suggested for the respondents in Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia, these intervals differ, though in this investigation they were regrouped and coded into three following intervals: 1 = Up to EUR 500, 2 = EUR 501–EUR 1000 Euro, and 3 = EUR 1001 and above. The most optimal for the international comparison and interpretation of the results intervals were selected. The additional measure 9 = N/N means that for various reasons there is no answer.

Variables based on all above-described questions were explanatory (or independent) variables in the analysis.

Among socio-demographic characteristics, the first concerns the age of respondents. The respondents were asked to write the number of their actual years of age. This way, in Estonia, respondents indicated ages between 15 and 93 years; in Lithuania, respondents indicated ages between 18 and 90 years; and in Latvia respondents indicated ages between 18 and 75 years. In this research, age numbers were regrouped and coded into three following intervals: 1 = up to 29 years old, 2 = 30–49 years old, and 3 = 50 years old and above. The most optimal age intervals were selected.

Next, the respondents were asked about their education level. An extended scale of education levels was suggested in the questionnaire. In this research, for the optimization of analysis and interpretation of the results, the scale is regrouped and coded into three following groups: 1 = basic or lower education, 2 = secondary and/or professional education, and 3 = university.

The next socio-demographic characteristic is household size. The respondents were asked to indicate the number of persons who live in their HH. This way, in Estonia, respondents indicated a number between 1 and 10 or more persons; in Lithuania, respondents indicated a number between 1 and 8. In this research, for the optimization of analysis and interpretation of the results, these numbers were regrouped and coded into the following intervals: 1 = live alone, 2 = two persons, 3 = three persons, and 4 = four or more persons.

The last socio-demographic characteristic is the size of the settlement where the respondent lives. The respondents were asked to mark on three measures: 1 = big city, 2 = another city, and 3 = village. The category “big city” included cities like Tallinn, Tartu, Pärnu, Narva, and Kohtla-Järve in Estonia, while in Lithuania and Latvia, this category included the capital cities only, i.e., Vilnius in Lithuania and Riga in Latvia.

Variables based on all above-described socio-demographic characteristics were control variables in the analysis.

Analysis of the empirical data starts from the descriptive statistics [

54,

55]. Due to the limitation of the volume of the paper, the descriptive statistics are not discussed and only presented in

Appendix A Table A1 and

Table A2. For all variables, distribution frequencies are presented in percentages. When it was reasonable, for selected variables, particularly for evaluations of perception of national security, and subjective living conditions, means of the values were calculated. For comparison of selected means, the ANOVA test was run. The latter test compares the mean values of two or more measures; the higher the value of the Fisher (F) coefficient, the higher the difference between the compared measures; and, conversely, when the value of F approaches zero that means a difference between the measures’ means does not exist [

56].

To test the hypothesis, a specific econometric model [

54] was created:

where a is constant (y-intersect); Y—dependent variable (“I feel safe living in my own country.”); X

1—explanatory (or independent) variable related to the statement (a); X

2—explanatory variable related to the statement (b); X

3—explanatory variable related to the statement (c); X

4—explanatory variable related to the statement (d); X

5—explanatory variable related to the statement (e); X

6—explanatory variable related to the statement (f); X

7—explanatory variable related to income per HH/per month; X

8—control variable related to age of respondent; X

9—control variable related to education level of respondent; X

10—control variable related to household size, and X

11—control variable related to size of the settlement, b

1,…,b

11—regression coefficients of the according variables Xi, when i = 1,…11.

Accordingly, a multivariate statistical analysis was conducted [

56,

57]. First, the method of correlation analysis was used to check the normality of distributions of dependent and explanatory variables, and the linearity of possible association between them. In general, correlation analysis measures the strength and direction of association between variables, among which may be rank order (ordinal and interval-ratio) variables [

55,

56]. The results of the correlation analysis (r) ranges from −1 to 1. The absolute values of r indicate the strength of the linear association between the two variables: r is closer to 1 where a stronger relationship exists, and r is closer to zero where a weaker relationship exists. Meanwhile, the signs ‘+’ or ‘−’show the direction of this relationship: a figure of ‘+1’ means that the two variables have a perfect positive association, while ‘−1’ means that the two variables have a perfect negative association, and zero indicates no association between the two measured variables. In our research, the Pearson correlation was carried out among the variables of perceptions of national security, and variables on objective and subjective living conditions. The results (

Table 1) revealed the existence of a linear association between the variables; therefore, analysis moved to linear regression analysis.

In general, the method of linear regression analysis measures how much a dependent variable depends on explanatory and control variables [

55,

56,

58]. In this investigation, eight linear regression analysis models were carried out. Prior to the application of regression, collinearity diagnostics to test a possible problem of multicollinearity were conducted [

56,

58]. Four main measures were taken into consideration: eigenvalue, condition index, tolerance, and a variance inflation factor (VIF). According to the literature [

56,

58], the closer to 0 measures of eigenvalue, the higher the intercorrelation of the predictors, and the possibility that a small change in the data values may mean large changes in the results of estimations. A condition index greater than 15 indicates a possible problem with collinearity; an index greater than 30 means a serious problem of collinearity. The closer to 0 measure of tolerance, and the higher the possibility of multicollinearity, and the inflation of the standard error of the regression coefficients. A variance inflation factor greater than 2 usually means a problematic situation with the multicollinearity. In our research, the measures of eigenvalue vary between 0.034 and 10.753; and measures of the condition index vary between 1.000 and 14.716. That means that a problem of multicollinearity does not exist, though measures of tolerance (varying between 0.289 and 0.957) and VIF (varying between 1.045 and 3.466) reveal some risk of the multicollinearity. To avoid such a problem, manipulations with the explanatory variables are continued by application of the factor analysis method.

In general, the method of factor analysis helps to model (or rearrange) the observed variables as linear functions into the “factors” [

56,

57]. For extraction of factors in our research, the principal components method was used, based on a fixed number of factors (

n = 3), and Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization. The results of the factor analysis were saved as new variables in the empirical database. The first factor F1 is titled “Perception of income via possibilities/activities beyond the HH” and is mostly associated with the statements: “I can afford to help other people asking for financial help”, “My current income allows me to set aside part of my income for savings”, and “I can spend money on leisure, travel, entertainment, and development” (

Appendix A Table A3). The second factor F2 is titled “Perception of income based on material conditions to fulfil daily needs” and is mostly associated with the statements: “I have no financial difficulties in paying utilities, rent, bank loans, leasing, and other liabilities” and “My current income allows me to purchase food and other necessities without worrying too much about expenses.” The third factor F3 is titled “Unconditional perception of income” and is mostly associated with the statement: “I am happy with my current income.”

The latter three new variables were included into the improved econometric model:

where a is constant (y-intersect); Y—dependent variable (“I feel safe living in my own country.”); X

1—explanatory variable based on factor F1; X

2—explanatory variable based on factor F2; X

3—explanatory variable based on factor F3; X

4—explanatory variable related to income per HH/per month; X

5—control variable related to age of respondent; X

6—control variable related to education level of respondent; X

7—control variable related to household size, and X

8—control variable related to size of the settlement, b

1,…,b

8—regression coefficients of the according variables Xi, when i = 1,…8.

Now, measures of eigenvalue vary between 0.040 and 5.671; and the measures of the condition index vary between 1.000 and 11.852, i.e., it is less than 15 (

Appendix A Table A4). The measures of tolerance vary between 0.697 and 0.974, i.e., rather distant from 0; meanwhile measures of the VIF vary between 1.026 and 1.436, i.e., no one measure exceeds 2 (

Appendix A Table A5). That means manipulations with factor analysis let us avoid risk of the multicollinearity.

Next, we conducted linear regression analysis with total cases, as well as separately for each analyzed country (

Table 2). The dependent variable in all these models is the same—perception of national security expressed by the statement, “I feel safe living in my own country.” Meanwhile, independent variables in some regression analysis models are explanatory variables only (Model 1, Model 3, Model 5, and Model 7), while in other regression models control variables included additionally (Model 2, Model 4, Model 6, and Model 8). For inclusion of exploratory and control variables into the regression models, an enter method was applied. The latter method means all variables are entered into the model in a single step [

55]. An interpretation of regression results is similar to interpretation of correlation results: the result of the regression analysis, in our case—standardized coefficient beta (β) ranges from −1 to 1; the closer β is to −1 or 1, the stronger the dependent variable depends on the explanatory variable; and the closer β to zero, the less the dependent variable depends on the explanatory variable. The signs ‘+’ or ‘-’show the direction of this relationship of dependence: a figure of ‘+1′ means perfect positive dependence, ‘−1′ means perfect negative dependence, and zero indicates no dependence between the two measured variables.

4. Research Results and Discussion

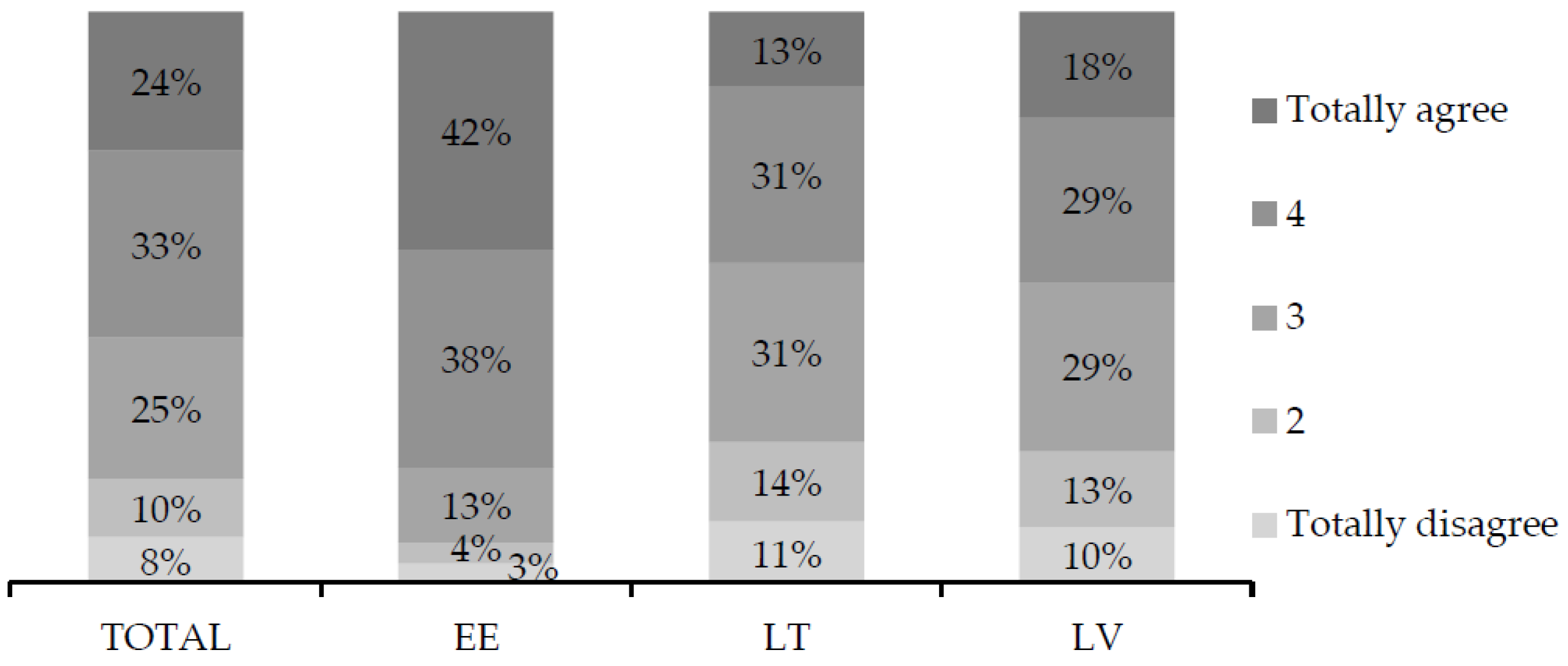

The percentage distribution of the variable on perception of national security reveals that more than half of the respondents in all the Baltic countries agreed that they feel safe living in their own country and, among all the respondents, 24% totally agree with such a statement (

Figure 1). Only 8% of the respondents stated that they totally disagree about feeling safe living in their own country.

The total mean of evaluations in the 5-point scale (where 1 = totally disagree and 5 = totally agree) is 3.6. Results in separate countries show that population opinions differ somewhat: in Estonia the mean measure is equal to 4.1, in Lithuania it is 3.2, and in Latvia 3.3. Meanwhile, the ANOVA test shows that such a difference is rather big and statistically significant (F = 187.983, p < 0.001). The latter results point to a need for the hypothesis to be tested precisely, considering not only total measures but also measures for each country (Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia) individually.

Furthermore, for analysis of the association between the perception of national security and actual (or objective) income, as well as subjective perception of income, the Pearson correlation analysis has been conducted. The results provided in

Table 1 show positive associations between feeling safe in the country and both objective and subjective perceptions of personal income. All measures are statistically significant. Therefore, it can be stated: the higher the objective perception of personal income, the more people feel safe in their country; and, conversely, the lower the objective perception of personal income, the less people feel safe in their own country.

The results of correlation analysis (

Table 1) also show the strongest association between the feeling of safety and the subjective perception of income, particularly, happiness with their own current income (r = 0.344) and having no financial difficulties in paying utilities, rent, bank loans, leasing, and other liabilities (r = 0.343). A lower, but still rather strong association is between feeling safe in the country and having income that allows an individual to purchase food and other necessities without worrying too much about expenses (r = 0.315), with the possibility of spending money on leisure, travel, entertainment, and development (r = 0.300). Meanwhile, feeling safe in one’s own country is associated with an objective perception of income (r = 0.206), with current income that allows them to set aside part of their income for savings (r = 0.264), as well with the possibility of helping other people asking for financial help (r = 0.227). These associations are rather weak, but still statistically significant. That is, the association of the feeling of safety in the country with the subjective perception of income is stronger than the objective perception of income. On the other hand, among subjective perceptions of personal income, some individuals more strongly than others associate this with a feeling of safety in the country. It seems that considerations related to the current situation, and the possibility of fulfilling individual and/or HH needs, are among the more important subjective living conditions for a feeling of safety.

The above results of the ANOVA test and

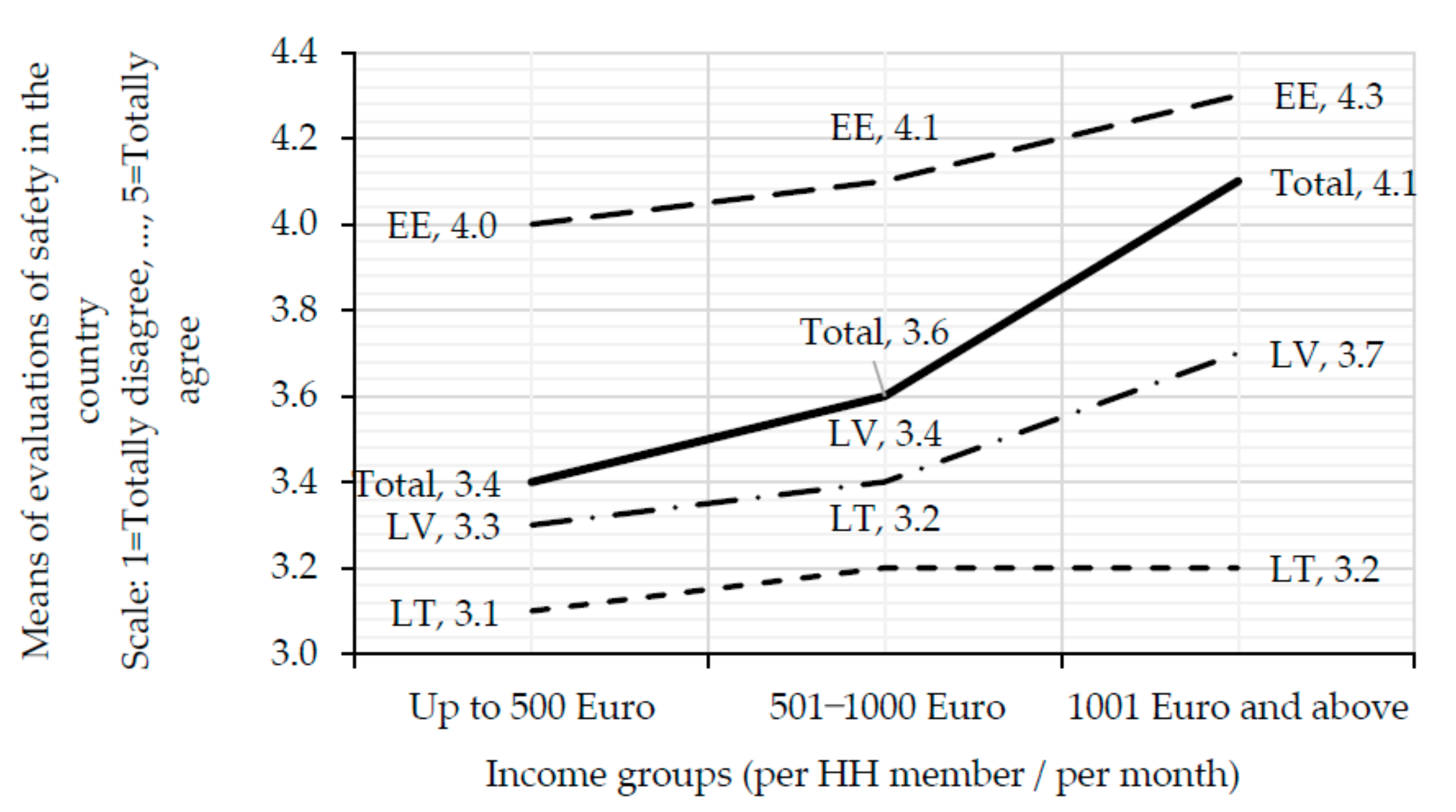

Table 1 strengthen the case for the hypothesis to be tested precisely and separately for each country selected for analysis. Therefore, for each country the means of evaluation of feeling safe in the country according to income per HH member/per month were calculated (

Figure 2). The results, first of all, show that evaluations of feeling safe are independent of income and are highest in Estonia, close to average in Latvia, and lowest in Lithuania. On the other hand, a linear increase in a feeling of safety evaluations together with an increase in income is evident in Estonia (means from 4.0 to 4.3) and Latvia (means from 3.3 to 3.7). Meanwhile, in Lithuania, such an increase in safety evaluations is not so evident (means from 3.1 to 3.2), although even such a small increase is associated with an increase in income. So, it could be presumed that a feeling of safety does depend on measures of objective personal income.

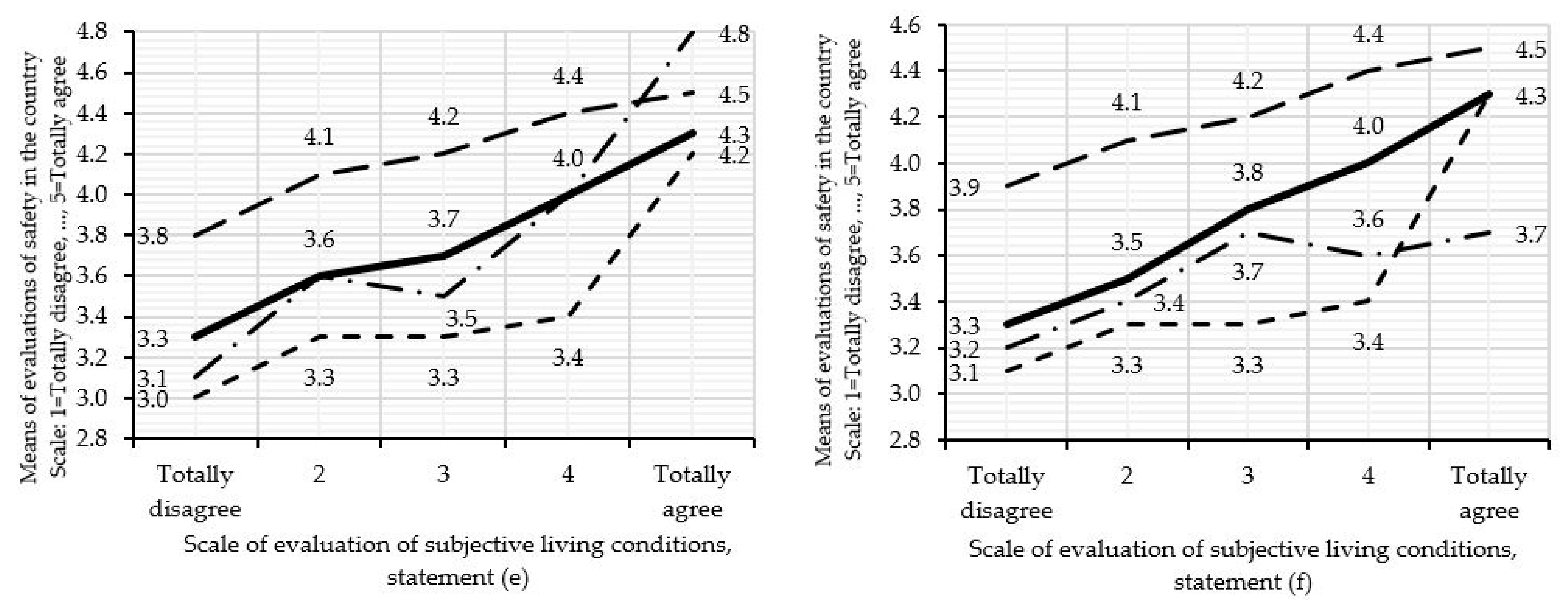

Furthermore, the association between the feeling of safety and the subjective perception of personal income in each Baltic country is reviewed. The results provided in

Figure 3 show an evident general trend: the higher the evaluation of a particular statement related to subjective perception of income, the higher the evaluation of the feeling of safety in the country. At the same time, it is evident that the evaluation of the feeling of safety in Estonia is higher than in the other two countries; meanwhile, in Lithuania, conversely, the evaluation of the feeling of safety is lower than in the other two countries. On the other hand, precise analysis shows that, in Latvia, evaluations of the feeling of safety often vary, especially in the high point of subjective perception of income. Even so, the above-mentioned linear association between the feeling of safety and subjective living conditions represented by personal income remains.

For identification of the determinants that influence the feeling of safety in the Baltic countries, linear regression analysis has been conducted (

Table 2). Results of the regression analysis for all the Baltic countries allow us to state that the feeling of safety statistically significantly depends as much on subjective perception of income as on objective personal income (Model 1 in

Table 2). On another hand, feeling safety stronger than on other explanatory variables depends on the factor F2, “Perception of income based on material conditions to fulfil daily needs” (β = 0.254,

p < 0.001) and less than on other variables in the Model 1, feeling safety depends on income per HH member/per month (β = 0.052,

p < 0.05). All β coefficients are positive and let us state: as more people agree with the statements on personal income, the more they feel safe living in their home country, and, in opposite, as less people agree with the statements on personal income, the less they feel safe living in their home country.

Inclusion of control variables into the regression model enhances the influence of the F1, “Perception of income via possibilities/activities beyond the HH” (β = 0.133,

p < 0.001), and F2, “Perception of income based on material conditions to fulfil daily needs“ (β = 0.262,

p < 0.001), but weakens the influence of the objective income per HH member/per month (β = 0.045,

p < 0.001) (Model 2 in

Table 2). Positive β coefficients, again, reveal that the more positive perception of the personal income, the more positive perception of safety in the country, and the opposite, although there is an additional, even if not strong, influence of the size of the settlement that indicates that the bigger the cities, the more positive feeling of safety in own country, and the opposite (β = −0.055,

p < 0.01).

Considering the differences among the countries identified in the above-described findings, it was decided to review the influence of objective and subjective perceptions of living conditions, as well as the socio-demographic characteristics of feeling safe in each of the three Baltic countries. For these reasons, six regression analysis models were constructed (Models 3–8 in

Table 2). The results show that the determinants related to the subjective perception of personal income always, in all six models, remain influential on feeling safe in the country. Meanwhile, objective income per HH member/per month does not influence perception of safety in the countries. At the same time, these determinants become less strong after inclusion of control variables based on socio-demographic characteristics. That is, the mentioned determinants are influential, though at different levels among various groups of populations. The trend is common to the Baltic countries such as Estonia and Lithuania, but not in Latvia.

In Estonia, the most influential is F2, “Perception of income based on material conditions to fulfil daily needs” (β = 0.283,

p < 0.001), and less influential is F1, “Perception of income via possibilities/activities beyond the HH” (β = 0.144,

p < 0.001) (Model 3 in

Table 2). Inclusion of control variables into the regression model enhances the influence of the F1, “Perception of income via possibilities/activities beyond the HH” (β = 0.150,

p < 0.001), and F3, “Unconditional perception of income” (β = 0.251,

p < 0.001), but somewhat weakens the influence of the F2, “Perception of income based on material conditions to fulfil daily needs” (β = 0.280,

p < 0.001) (Model 4 in

Table 2). The latter trend is mostly related to the education level of the population: the higher the education level, the more positive the feeling of safety in the country, and the opposite (β = 0.080,

p < 0.05). The relationship is not strong, though it is statistically significant.

In Lithuania, again, the most influential is F2, “Perception of income based on material conditions to fulfil daily needs” (β = 0.245,

p < 0.001), and the less influential is F1, “Perception of income via possibilities/activities beyond the HH” (β = 0.085,

p < 0.05) (Model 5 in

Table 2). Inclusion of control variables into the regression model slightly enhances the influence of the F1, “Perception of income via possibilities/activities beyond the HH” (β = 0.090,

p < 0.05) and F3, “Unconditional perception of income” (β = 0.234,

p < 0.001), but weakens the influence of the F2, “Perception of income based on material conditions to fulfil daily needs” (β = 0.253,

p < 0.001) (Model 6 in

Table 2). The latter trend is related to the size of the settlement and the bigger the city, the more it is related to the positive feeling of safety in the country, and the opposite (β = −0.097,

p < 0.01).

In Latvia, the most influential is F3, “Unconditional perception of income” (β = 0.221,

p < 0.001) and the less influential is F1, “Perception of income via possibilities/activities beyond the HH” (β = 0.118,

p < 0.05) (Model 7 in

Table 2). Inclusion of control variables into the regression model makes absolutely minimal changes in F1, “Perception of income via possibilities/activities beyond the HH” and F3, “Unconditional perception of income”, and it can be stated that socio-demographic characteristics do not have any influence on the relationship between feeling safe in the country and objective or subjective perceptions of living conditions.

As the authors mentioned in the introduction of this article, there is a lack of research examining the impact of the income of the population on perceived national security. Therefore, we can compare only some of the obtained results with only certain insights of other studies. The results of the investigation reveal that more than half of the respondents in the three Baltic countries—Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia—agreed that they feel safe living in their own country. The results of this research in some sense converge with the findings by Janušauskienė et al. [

16], stating that 63 percent of Lithuanians say they feel safe. Socio-demographic characteristics, such as size of the settlement and education, make the strongest influence on perceived security in the Baltic states, especially in Estonia and Lithuania. Meanwhile, the findings of Janušauskienė et al. [

16] highlight the age of the respondents as the factor influencing the perception of security in Lithuania. Moreover, the results of the study showed that the objective and subjective incomes of society play a significant role in the context of national security. In the previous study, Janušauskienė et al. [

16] provided a very similar insight, stating that people who are more affluent feel safer than those who are poor. Additionally, the results demonstrate that the association of the feeling of safety in the country with subjective perception of living conditions is stronger than objective perception. This finding reflects the attitudes of Stoetman [

49] and Janušauskienė et al. [

16], revealing that a gap exists between the reality of security and the individuals’ perceptions of security. According to Cialani and Mortazavi [

43], subjective measures capture the economic utility level reflecting an individual’s satisfaction, derived through the maximization of the consumption of goods, services, and leisure within budgetary constraints. Moreover, income not only allows individuals to purchase goods and services [

42,

43] but it also goes hand in hand with happiness and life satisfaction [

44,

59,

60]. Additionally, research results have revealed that three determinants, relating to the statements (a) “I am happy with my current income,” (b) “My current income allows me to purchase food and other necessities without worrying too much about expenses,” and (c) “I have no financial difficulties in paying utilities, rent, bank loans, leasing, and other liabilities” are the most influential on perception of security. Particular attention should therefore be paid to reducing poverty and social exclusion. This insight of the study directly responds to the critical indicators—income inequalities and poverty—identified in the reports of the European Commission [

61,

62] in Lithuania and Latvia. These indicators also relate to sustainable development goals, such as elimination of poverty (1SDG) and reduced inequalities (10 SDG). It should be noted that this study was limited to revealing the links between economic security indicators related to the income of the population and security perceptions; it did not examine respondents’ attitudes toward other security factors, such as political security, energy and natural resources security, homeland security, cybersecurity, human security, and environmental security [

3] and their impact on national security. Given the holistic approach to national security and the fact that there is no area of public life that would not affect national security [

4], in the long run it would be appropriate to extend the study by linking the insights gained to the activities of the authorities responsible for ensuring public and national security. Only cooperation between state authorities and the public could strengthen both the objective and the subjective senses of national security of the society. That is even more so when modern challenges and threats call for measures to reduce the likelihood of adverse events occurring. Government decisions on effective socioeconomic measures could help find a way out of poverty and income inequality and, at the same time, they could ensure a sense of security for the population.

5. Conclusions

Economic security is one of the key components of national security. The areas of security are complex, encompassing a number of interrelated factors, with close correlations and causal links. An objective and subjective perception of income plays an important role in achieving a sense of security. The authors of this investigation focus on the effect of objective and subjective individuals’ incomes on perceived national security in the Baltic countries.

The percentage distribution of the variable on the perception of safety reveals that more than half of the respondents in all Baltic countries agreed that they feel safe living in their own country. Only 8% of the respondents stated that they totally disagreed about feeling safe.

The results of the investigation reveal that evaluations of feeling safe independently of income are highest in Estonia, close to average in Latvia, and lowest in Lithuania.

Empirical data collected in the representative survey confirm the hypothesis that both objective and subjective perceptions of living conditions are significant determinants influencing a sense of safety in populations. Moreover, it can be stated that the higher the levels of objective and subjective perceptions of personal income, the more people feel safe in their country. In contrast, the lower the objective and subjective perceptions of personal income, the less people feel safe in their country.

Notwithstanding, the second part of the hypothesis should be rejected because empirical research reveals that subjective, but not objective, living conditions expressed in personal income are a more important determinant for the perceived security in the countries under consideration. Among the subjective living conditions, identified as determinants of feeling safe in the country, the most strong are happiness with their own current incomes and having no financial difficulties in paying utilities, rent, bank loans, leasing, and other liabilities, and, also, in purchasing food and other necessities without worrying too much about expenses. That is, the feeling of safety is strongly and positively associated with the subjective perception of an income that allows the fulfilment of daily personal and household needs. Less influential determinants related to subjective perception of income vary from country to country and depend on the list of possible determinants. There are few determinants that exert less influence on feeling safe in the country: these are associated with the subjective perception of living conditions like having a current income that makes it possible to set aside part of the income for savings, being able to spend money on leisure, travel, entertainment, and development, and being able to help other people who are asking for financial help.

Finally, it is to be noted that socio-demographic characteristics have had statistically significant but rather weak impact on objective and subjective perceptions of living conditions in the context of feeling safe in the country. Among such characteristics, the most significant are size of the settlement and educational level.

The insights of this investigation could be applied to ensure both national and economic security and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals 2030, such as elimination of poverty (1SDG) and reduced inequalities (10 SDG). Poverty and inequality are areas where government action and solutions are particularly needed in the Baltic states. People who are more affluent feel safer than those who are poor. A person’s relationship with the state is shaped first and foremost by the satisfaction of their individual needs. The study’s insights show that to ensure a sense of security in the country, particular attention needs to be paid to tackling the problems of poverty and inequalities.

It should be noted that this study is limited to revealing the impact of economic security indicators related to people’s incomes on perceptions of national security. It did not explore respondents’ perceptions of other security factors such as political security, energy and natural resource security, cyber security, environmental security, and other factors. Given the holistic approach to national security, it would also be useful to extend the survey in the future to reveal the impact of the Russian invasion into Ukraine on the perception of national security.