Abstract

In 2021, the European Commission set out the direction of changes in the field of European enterprise activities by establishing the principles of Industry 5.0. One of the indicated directions was the implementation of sustainable development principles in European industry. The aim of this article is to examine the level and nature of competences in the field of sustainable development among students at two Lublin universities: the Lublin University of Technology and the University of Life Sciences in Lublin. This is to enable the assessment of students’ preparation for the implementation of sustainable development principles in their future professional activities. The research sought to determine the relationship between the type of university and the competences of students, through the self-assessment of competences. The conceptualization and operationalization of competences in the field of sustainable development was based on the de Haan and Cebrian models, respectively. The tool used was the author’s own questionnaire based on the self-assessment of 25 statements, grouped into five areas of competence: knowledge, action, values and ethics, emotions and systems thinking. The results of the study confirmed differences between students in the areas of knowledge and activity. However, a relationship between the type of university and self-esteem in areas related to systemic thinking, emotions, and ethics and values was not found. Various self-assessment patterns (clusters) were observed in individual areas among the respondents. Differences in the assessment of the statements indicated the existence of factors that influenced responses. The results of the study confirmed the usefulness of the tool in identifying competency gaps of students based on which the tool can be recommended for use in the design of study programs.

1. Introduction

In 2021, the European Commission formally called for the fifth industrial revolution (Industry 5.0), following numerous discussions with research and technology organizations. The process was initiated through the official publication of a document entitled ‘Industry 5.0: Towards a sustainable, human-oriented and resilient European industry’ [1]. This document was preceded by earlier attempts to introduce the fifth industrial revolution occurring since 2017.

The introduction of the Industry 5.0 concept resulted from the evaluation that Industry 4.0 focused more on digitization and AI-based technologies and less on the original principles of social justice and sustainable development (SD) [2]. The concept of Industry 5.0 adopts a different point of view, emphasizing the importance of research and innovation in supporting industry in its long-term service to humanity within the limits of the planet [1]. None of the previous industrial revolutions—neither the first, introducing steam engines into production, nor the second, giving rise to mass production using electricity, nor the third, involving the automation of certain processes through electronic devices and information technology, not to mention the fourth, relating to the digitization of processes—had sustainable development content in their agendas.

For industry not to overuse the planet’s limited resources, it must be sustainable. It must develop circular processes that allow for the recycling and reuse of natural resources, reduction in waste and negative environmental impacts, leading to a circular economy [2]. This perspective enables industry to achieve social objectives that go beyond job creation and economic growth. In this perspective, industry provides a guarantee of prosperity while respecting the limited capabilities of our planet and placing the welfare of employees at the heart of the production process.

Industry 5.0 stems from the need identified by the European Commission to better integrate European social and environmental priorities with technological innovation and to change the focus from individual technologies to a systemic approach. For industry to recognize the need to design technologies focused on promoting future social values, it needs to rethink its position and its role in society [3].

The Industry 5.0 concept is a recent one and there has been little research in this area to date. Efforts are only now being made to build research tools for testing students’ competences [4]. This study is pioneering as it presents a tool for examining competences in the field of sustainable development with results of its application in a study of engineering students conducted at two universities in Lublin.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Role of Higher Education in Promoting Sustainability

Engineering education is essential to achieve sustainability in the world through the development and deployment of sustainable technologies and sustainable technological innovation. Thus, it plays an important role in the implementation of Industry 5.0 principles.

Promoting sustainability by engineering universities requires engineering education to be closely integrated with the concept of SD. Universities have a key role in promoting sustainable development. This task was assigned to higher education for the first time in 1972 at the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) [5]. Actions taken in subsequent years resulted in the publication of official documents that emphasized this responsibility. These included the Belgrade Charter of 1975 [6], the Tbilisi Declaration of 1977 [7] and the Brundtland Report, which particularly emphasized the role of teachers, stating, ‘teachers in the world [...] have a key role to play in helping to bring about the extensive social changes needed for sustainable development’ [8]. The key role of education was further underlined in Agenda 21 of the United Nations ‘for promoting sustainable development and improving the capacity of the people to address environment and development issues’ [9]. More recent examples include the so-called ‘Ubuntu Declaration’ of 2002, which, for the first time, referred to the need to integrate sustainable development principles into curricula at all levels of education [10], the 2005 Global Action Plan ‘Education for Sustainable Development’ [11], and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular, the formulation of Goal 4 ‘quality education’, which aims to ensure that ‘all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development’ [12].

However, the attribution of a responsibility to contribute to sustainable development to higher education was not solely due to the influence of external policies/activities. Since the 1990s, there has been greater and greater spontaneous involvement of higher education institutions in the promotion and implementation of sustainable development principles. The 1990 Talloires Declaration, which was the first official declaration by university authorities on the inclusion of sustainable development in teaching and research, the 1993 COPERNICUS Charter [13], which highlighted universities’ commitment to sustainable development, which was renewed in 2011, and the 2009 Turin Declaration on Education and Research for Sustainable and Responsible Development, serve as examples [14,15]. All these international declarations represent a commitment by higher education institutions to support and promote sustainable development, which has led to significant initiatives, such as the greening of campuses [16]. Despite the initiatives taken, however, there have been repeated criticisms that such commitments are not sufficient to significantly and permanently change institutional practices in higher education [17]. Research conducted on groups of graduates has confirmed that graduates do not have sufficient knowledge of environmental issues [18]. This has led to the conclusion that there is a need for stronger integration of SD topics into existing study programs [19].

2.2. The Place of Sustainability in Engineering Education

The statement that engineers and engineering education are necessary to achieve sustainable development, including the implementation of sustainable technologies and sustainable system innovations, is unquestionable [20]. This implies the implementation of SD in engineering education. At the beginning of the education for sustainable development (EfSD) decade, it was considered important to identify outstanding examples and best practice in the integration of SD in engineering education. These examples should include not only methods of teaching sustainable development and innovative educational practices developed in specific course programs, but also cases of how sustainability has been successfully integrated into the current engineering paradigm and into engineering educational institutions.

In most industrialized countries, a new trend in engineering education is to go beyond a technical focus and to expand curricula to include the teaching of social and management skills such that the ethical and social aspects of technology are integrated into university courses. De Graaff and Ravesteijn described this as ‘complete engineer training’ [21]. Moreover, Mulder [22] suggested that sustainability is a tool that can open doors in engineering institutions enabling modernization of the traditional engineering paradigm. Such a paradigm shift may narrow the ‘gap’ between technology and society.

In engineering education, environmental issues are often addressed at the level of engineering tools and methods, ignoring the holistic nature of sustainable development, its social component and the principles of equality. For effective implementation of sustainable development [22], it is not enough to include a social sciences course in the engineering curriculum. It is necessary to change the existing engineering paradigms, broaden the mental framework and embrace changes in values and basic assumptions [23]. Some technical universities have introduced such innovative activities. These include TU Delft, where, in 1998, the authorities decided to integrate SD into all engineering curricula and to create the possibility for graduates to specialize in sustainable development in all curricula instead of offering separate SD programs. The rationale was that every student should have a basic understanding of sustainability, sustainable technologies and the way in which sustainability related to their own engineering discipline.

2.3. Competency Classifications

The introduction of sustainable development into curricula in higher education has led to research into the associated competences [24,25,26]. These competences, including knowledge, skills and attitudes, are means of representing the intended learning outcomes [27,28]. In recent years, several authors have undertaken work on competences in the field of education for sustainable development.

According to de Haan [29], the key elements of sustainability competence include: competence to think in a forward-looking manner, to deal with uncertainty, and with predictions, expectations and plans for the future; competence to work in an interdisciplinary manner; competence with respect to open-mindedness, transcultural understanding and cooperation; participatory competence; planning and implementation competence; ability to feel empathy, sympathy and solidarity; competence to motivate oneself and others; and competence to reflect in a distanced manner on individual and cultural concepts. Poza-Vilches and colleagues [30] defined a reduced set of seven competences, including: systemic thinking, anticipation, legislation, strategic, collaboration, critical thinking and self-awareness.

Wiek et al. (2011) proposed five general groups of competences, including: systems-thinking, anticipatory, normative, strategic, and interpersonal competences [31].

Rieckmann (2012) proposed twelve competences, including: systemic thinking and handling of complexity, anticipatory thinking, critical thinking, acting fairly and ecologically, cooperation in (heterogeneous) groups, participation, empathy and change of perspective, interdisciplinary work, communication and use of media, planning and realizing innovative projects, evaluation, and ambiguity and frustration tolerance [32].

Lambrechts et al. (2013) identified six competences: responsibility, emotional intelligence, system orientation, future orientation, personal involvement, and ability to take action [25].

Brundiers et al. (2021), adopting a Delphi approach, updated the set of competences developed by Wiek et al. [31], suggesting the following: integrated problem-solving, interpersonal, implementation, strategic thinking, values thinking, futures thinking, and systems thinking [33].

Lozano et al. [34,35] synthesized the existing sets of competences by extending their number to twelve, including: systems thinking; interdisciplinary work; anticipatory thinking; justice, responsibility, and ethics; critical thinking and analysis; interpersonal relations and cooperation; empathy and change of perspective; communication and use of media; strategic action; personal involvement; assessment and evaluation; and tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty [35]. This compilation was used for empirical research (conducted both in Europe and elsewhere), in which the diagnosis of competences was systematically linked to the pedagogical approach aimed at shaping them [34].

Mula and colleagues [36] suggested that the nature of the required competences in the field of SD was becoming established. However, they suggested that there were serious concerns about the lack of conceptual clarity of the proposed competences and the ways in which they were developed, supported and evaluated.

2.4. Areas of Competence in Sustainable Development

Sustainable development is a constantly evolving concept because human-environment relations are complex and dynamic [37]. People and organizations learn every time they need to adapt to a changing environment, and the environment reacts to changes in human behavior and resulting actions. Consequently, it should be assumed that a readily available, once-defined knowledge and skills package that automatically leads to the implementation of SD does not exist. This challenge is easier to meet by operating in a broader category than competences, namely: areas. Such an approach enables a quick response to the need to establish new competences in the field of sustainable development. An example of such an approach is the CSCT model.

The CSCT (curriculum, sustainable development, competences, teacher training) model, in its original form, referred to the competence of teachers in the field of SD and focused on the teacher as an individual, an employee of an educational institution and as a member of a given society. It assumed that effective education in the field of sustainable development at every level of teaching requires teachers to have competences related to each of these roles [38]. Therefore, the model considers the entire personality of the teacher in terms of sustainable development, not only their professional sphere.

The model was developed as part of the Comenius-2 project by 15 European universities associated with the Environment and School Initiatives (ENSI) network [39]. It defines ESD learning objectives as the acquisition of skills with respect to:

- understanding and changing one’s own living conditions,

- participating in collective decisions,

- having solidarity with those who, for various reasons, are unable to control their own living conditions.

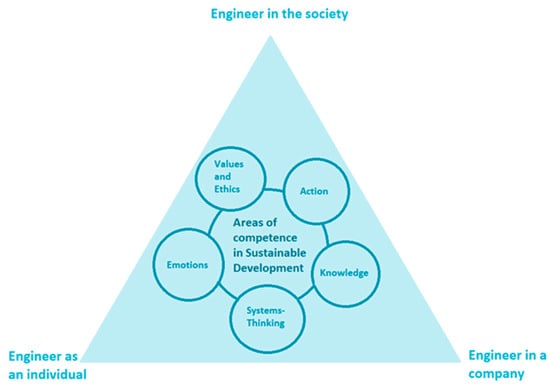

The model indicates the competence areas necessary to consciously achieve the ESD educational goals which can inform the creation of innovative educational programs in the field of SD. Model areas that form the framework for education in the field of sustainable development include: knowledge, systemic thinking, emotions, values, ethics, and action (Figure 1). These play the role of a filter through which competences in the field of sustainable development are perceived. The authors of the model suggest that the competences desired within the separate areas should be more of an attribute of a group than of an individual [38]. The CSCT model is intended to enable the development of an educational offer for all levels of education. It implies a more comprehensive educational offer, the aim of which is to consider the complexity of sustainable education by means of a holistic approach. At the same time, the authors suggest that competence models should focus on occupational-specific core competences if they are to be used as a basis for the concept of sustainability education and further training. This assumes that the type of education may result in differentiation in the competence profile of graduates.

Figure 1.

Model for areas of competence in the field of sustainable development for engineers. Source: Author’s own compilation based on Sleurs [38].

As engineers perform similar roles to teachers, i.e., they are individuals, employees of enterprises and members of a given community, it was considered reasonable to use this model in the present research on future engineers.

3. Materials and Research Methods

The aim of the present study was to determine the level and structure of competences in the field of SD of engineering students at the Lublin University of Technology (LUT) and the University of Life Sciences in Lublin (ULS). Both universities educate engineers, but with a different profile, preparing students for the implementation of sustainable technologies and system innovations in different areas. In the case of LUT, the focus is on areas of engineering related to technology and industry, and in the case of ULS, the focus is on areas related to the environment. Theoretical considerations enable the proposal of five hypotheses with respect to the diversity of self-assessed competences in the field of SD depending on the university:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Due to the specificity of the universities and the scope of knowledge transferred, LUT and ULS students differ in their competences in the field of SD.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Students’ competences in the field of SD in the area of systemic thinking do not vary depending on the university, since they formed in earlier stages of education.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Students’ competences in the field of SD in the area of emotions do not vary depending on their university, because they are shaped in earlier periods of life.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Students’ sustainable development competences in the area of ethics and values do not vary depending on the university, because they are shaped in earlier periods of their life and moral development.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Students’ competences in the field of sustainable development in the area of activity do vary depending on the university, because they are shaped and created during the students’ studies.

To test the hypotheses, the research included a group of 308 students of LUT and ULS (Table 1). The study was conducted using an SD self-assessment questionnaire [40] which was based on the classification of competences by Cebrian and colleagues [41]. In order to create a more general picture of SD, 25 questions were grouped into five areas, according to the five domains of the CSCT competences model, i.e., knowledge, systems thinking, emotions, ethics and values, action [42]. The self-assessment questions were closed, with the answers rated according to a 5-point Likert scale. The research was preceded by multiple pilot studies. The questionnaire was also evaluated by experts comprising other researchers from the unit. The data were collected using the CAWI technique.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics.

After the study, the reliability of the scales used was determined. The statistical analysis for each area of competences was conducted in an analogous way involving the following:

- Firstly, a k-means clustering method was applied to group cases into clusters based on answers to questions which were characteristic for a given area of competence. Guided by indices recognized in the literature, the number of clusters was determined using the NbClust package [43]. Each identified cluster represented a different attitude towards the competence for a particular area;

- Secondly, a Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of various for ranks and Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction were applied to determine whether differences in the assessment of individual statements by people included in the identified clusters were statistically significant, which made it possible to determine whether the clusters differed significantly [44];

- Lastly, a chi-square test of independence was used to check whether there was a relationship between the university attended and belonging to a specific cluster [44].

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistica TIBCO package.

4. Research Results

4.1. Domain—Knowledge

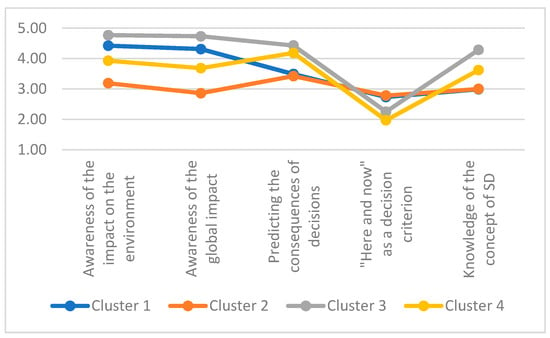

In the area of knowledge, four clusters with respect to the self-assessment of competences were distinguished, with 90, 64, 56 and 98 cases per cluster, for clusters one to four, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cluster chart for competence self-assessment in the field of knowledge. Source: Author’s own compilation.

Respondents included in individual clusters differed in the assessment of competences represented by the five statements relating to the analyzed area (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of clusters in the field of knowledge.

Individual clusters differed in the assessment of individual statements. To determine the significance of these differences, a Kruskal–Wallis test and a Dunn post hoc test were carried out for each. For each of the statements, the null hypothesis was tested, assuming that its assessment was the same in each cluster. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test for individual statements in the field of knowledge.

The data from Table 3 allow to bring about an alternative hypothesis: the respondents qualified for individual clusters differed in the self-assessment of individual statements.

The obtained p-values indicated a significant difference in self-assessment ratings of individual statements provided by the respondents included in each cluster. The Dunn post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction indicated that, in the case of statements 1 and 2, there were significant differences between the ratings for respondents belonging to each cluster. With respect to statement 3, differences in ratings were observed for respondents included in cluster 1, in comparison with clusters 3 and 4, and for those included in cluster 2, also in comparison with clusters 3 and 4. Regarding statement 4, the self-assessment of individuals in cluster 1 differed significantly from those in cluster 3 and 4. This was also the case for cluster 2. In the case of statement 5, clusters 3 and 4 differed significantly from each of the other clusters, while the self-assessments of statement 5 for clusters 1 and 2 differed from that for both clusters 3 and 4.

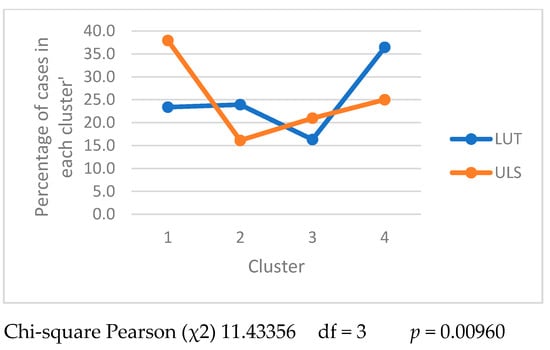

The analysis presented in Figure 3, showing the size of clusters in the studied universities, shows that there were differences between the groups of engineers from LUT and ULS. The value of the chi-square test supported rejection of H0 and the acceptance of the alternate hypothesis that a relationship existed between the two variables, university attended and membership of a specific cluster.

Figure 3.

The size of clusters in the area of knowledge in the studied universities. Source: Author’s own compilation.

4.2. Domain—Systemic Thinking

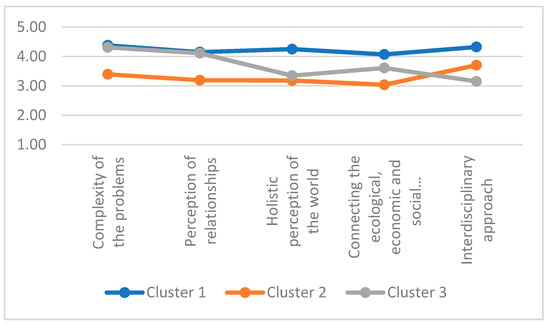

In the area of systemic thinking, three clusters were distinguished (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cluster chart for self-assessment of competences in the area of systemic thinking. Source: Author’s own compilation.

The results presented in Figure 3 suggest the existence of two clearly different clusters (clusters 1 and 2 comprising 178 and 84 cases, respectively) and the existence of an intermediate cluster (cluster 3 comprising 46 cases). Cluster 3 responses were similar to some extent to those of respondents from cluster 1 (the first two statements), but were also similar to an extent to the self-assessment of respondents constituting cluster 2 (statement 3). With respect to the self-assessment of statements 3 and 4, however, these were not similar to any of the other groups. These similarities and differences are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Characteristics of clusters in the area of systemic thinking.

The Kruskal–Wallis test indicated that the differences described were statistically significant (Table 5). The observed significant differences (applying Dunn’s test) related to self-assessment of statements 1 and 2 (clusters 1 and 2 and clusters 2 and 3), statement 3 (cluster 1 from 2 and 3), and statements 4 and 5 (all clusters).

Table 5.

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test for individual statements in the area of systemic thinking.

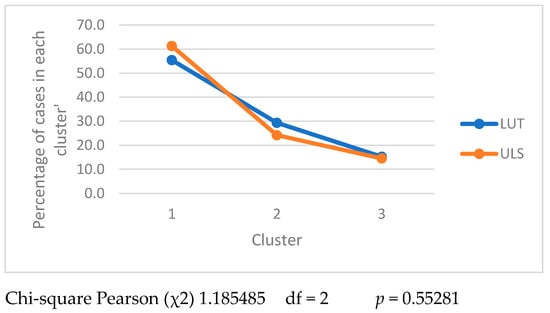

Figure 5 shows that there was no relationship between university attended and belonging to a given cluster, which was confirmed by the results of the chi-square test.

Figure 5.

The size of clusters for the area of systemic thinking in the universities studied. Source: Author’s own compilation.

4.3. Domain—Emotions

In the area of emotions, four clusters were distinguished (Figure 6) with 88, 110, 48 and 62 cases, respectively. Not all statements had the same discriminatory power (Table 6).

Figure 6.

Cluster chart for self-assessment of competences in the area of emotions. Source: Author’s own compilation.

Table 6.

Characteristics of clusters in the area of emotions.

The Kruskal–Wallis test results showing differences in the self-assessment of individual statements by respondents in individual clusters are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test for individual statements in the field of emotions.

Statistically significant differences (Dunn’s test) were observed for the following: in the self-assessment of statement 1—groups 1 and 4, 2 and 4, 3 and 4; in the self-assessment of statement 2—groups 1 and 2 and 3, groups 2 and 3 and 4; in the self-assessment of statements 3 and 4—group 4 from groups 1, 2 and 3. In the self-assessment of statement 5, group 3 differed statistically significantly from every other group.

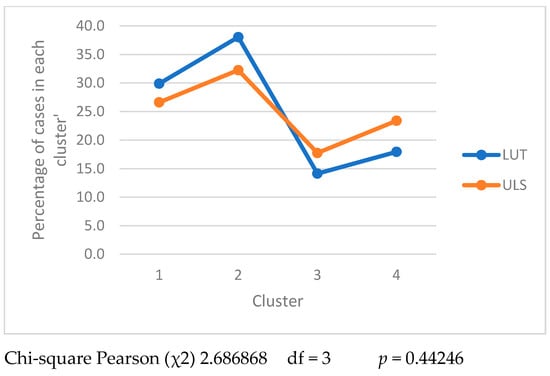

Figure 7 indicates that there was no relation between university attended and belonging to a given cluster, which was also confirmed by the chi-square test result.

Figure 7.

The size of clusters in the area of emotions in the studied universities. Source: Author’s own compilation.

4.4. Domain—Ethics and Values

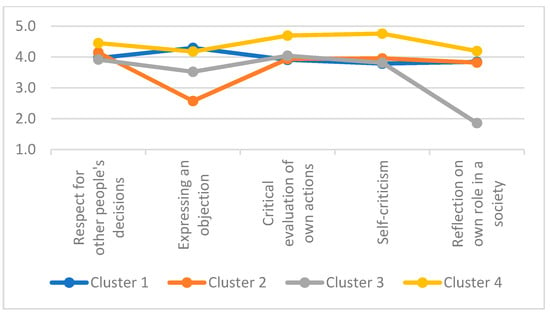

In the area related to ethics and values, four clusters were distinguished (Figure 8) numbering 124, 61, 71 and 52. The average self-assessments for individual statements in each cluster are presented in Table 8.

Figure 8.

Cluster chart for self-assessment of competences in the area of ethics and values. Source: Author’s own compilation.

Table 8.

Characteristics of clusters in the area of ethics and values.

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test (Table 9) and the Dunn test indicated that differences in the self-assessment of individual statements were significant.

Table 9.

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test for individual statements in the field of ethics and values.

In the self-assessment of statement 1, statistically significant differences were found for groups 1, 2 and 3; 2, 3 and 4; as well as for 3 and 4. In the self-assessment of statement 2, statistically significant differences were found between group 4 and every other group, and between groups 1 and 2 and 3.

The analysis of Figure 9 presenting the size of clusters in the studied universities showed some similarities and differences. However, the value of the chi-square test obtained did not allow for the rejection of H0 indicating that there was no relationship between the variables.

Figure 9.

The size of clusters in the area of ethics and values in the universities studied. Source: Author’s own compilation.

4.5. Domain—Action

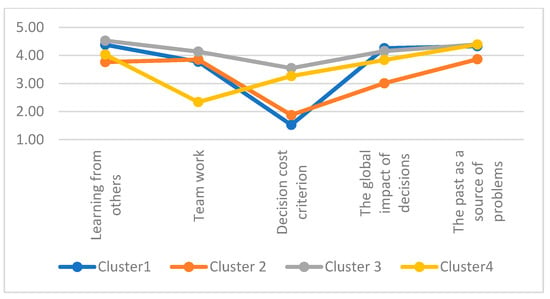

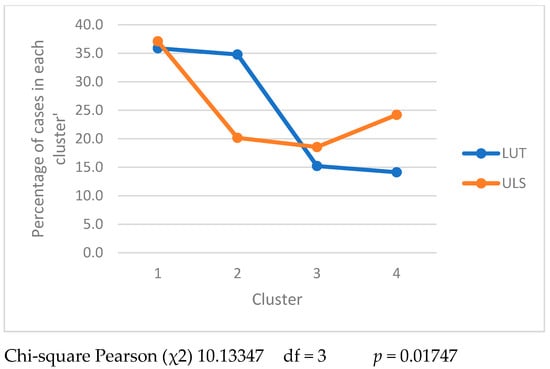

In the area related to activity, four clusters were distinguished (Figure 10) numbering, respectively, 112, 89, 51 and 56 respondents. The average self-assessment for individual statements is presented in Table 10.

Figure 10.

Cluster chart for self-assessment of competences in the area of activity. Source: Author’s own compilation.

Table 10.

Characteristics of clusters in the area of action.

Analyses carried out using the Kruskal–Wallis test and the Dunn test indicated statistically significant differences in the self-assessment of individual statements (Table 11).

Table 11.

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test for individual statements in the field of action.

In the self-assessment of statement 1, statistically significant differences were found for groups 1 and 2 to 4, 2 and 3 and 3 and 4. For statement 2, the self-assessment ratings for cluster 4 were significantly lower than for respondents representing all other clusters. Self-assessments of statement 3 made by respondents in cluster 1 were higher than the self-assessments reported by respondents from other clusters. There was also a difference between the representatives of clusters 3 and 4. Statistically significant differences in the self-assessment of statement 4 occurred between groups 1 and 2, and 1 to 3 and 4. Differences in the self-assessment of statement 5 were observed for respondents forming clusters 1 and 2; 2 and 3, 2 and 4.

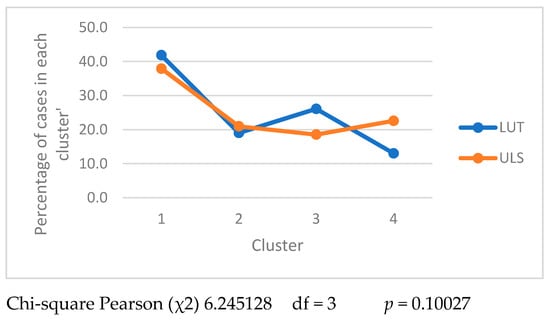

The analysis of Figure 11 shows that the self-assessment of LUT and ULS students showed different patterns, which was confirmed by the chi-square test.

Figure 11.

The size of clusters in the area of action in the universities studied. Source: Author’s own compilation.

5. Discussion and Directions for Further Research

Universities are credited with having a significant impact on the process of creating a responsible, sustainable society. Lecturers should focus not so much on knowledge as on the competences of students in the area of sustainable development [45]. To determine levels of competence, the present study was conducted to evaluate specific hypotheses. The hypotheses that there are significant differences between LUT and ULS students with respect to competences related to knowledge and action were confirmed (Hypotheses 1 and 5). The hypotheses that there are no relationships between the type of university and self-assessed competence in areas related to systemic thinking, emotions, ethics and values were also supported. It should, however, be emphasized that the surveyed students of both universities rated their competences in the field of SD highly. This high self-assessment is consistent with the results of other studies on SD competences. Students in the UAE [46] showed a high level of concept awareness, a strong positive attitude and moderately positive behavior with respect to education for SD. However, research carried out under the RUCAS project [47] indicated that European students had a more favorable attitude towards sustainable development than students from the Middle East [48]. Moreover, research at the University of Cairo [49] showed that students of individual colleges differed in the level of competences in the field of sustainable development. The same research also showed variation in the comprehensive provision of SD content in education programs in individual faculties. Wright and Froese, who conducted research [50] on Canadian civil engineering students, highlighted the lack of such content in education programs.

In the present study, among the respondents, different patterns (clusters) of self-assessment were observed in individual areas. These differences indicated the existence of factors other than the type of education in shaping competences. In this respect, the research conducted among students of two Lublin universities is consistent with the results obtained by other researchers [49], supporting the view that formal education is only one of the determinants of competences in the field of SD.

Preparing future engineers to operate in a sustainable environment and creating such an environment requires more than only incorporating a social sciences course into engineering curricula. It requires, above all, changes in the existing engineering paradigms, broadening the mental framework and changing value systems and basic assumptions [36]. It is important, therefore, to identify discrepancies in this respect between the current and the desired state. Therefore, it is worth examining which elements of knowledge about the natural environment students in engineering faculties at technical universities need, and which elements of technical knowledge students in engineering faculties at natural universities need.

Another direction for investigation is to conduct cross-country comparisons to determine if there are differences in how the competence paradigm for SD is developed. The discourse to date has been dominated by North American and European perspectives, which implies cultural influence in the definition and interpretation of these competences [36].

There is also a deficit in research related to the institutional context of shaping behavior in the field of sustainable development. This applies to both institutions, such as NGOs, and to systems, including the education system or the legal system.

In the context of the education system, future research should include the consideration of methods leading to more effective education in the field of sustainable development, including pedagogical methods related to e-learning. In an era of accelerated technological development, this issue has particular importance in relation to engineering students.

In the future, current students will become decision makers in the area of development. Implementation of the concept of Industry 5.0 requires competence in fields related to the development of technology, as well as in social and environmental areas. Only an engineer competent in each of these areas can ensure that the planet develops sustainably.

Author Contributions

Both authors (B.M. and A.W.) confirm that their contribution in each stage of the preparation of this article was equal. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Breque, M.; Nul, L.D.; Petridis, A. Industry 5.0: Towards a Sustainable, Humancentric and Resilient European Industry; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; ISBN 978-92-76-25308-2. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Wang, L. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.Y.; Xu, X.; Klotz, E.; Newman, S.T. Intelligent Manufacturing in the Context of Industry 4.0: A Review. Engineering 2017, 3, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titko, J.; Tambovceva, T.; Atstaja, D.; Lapinskaite, I.; Solesvik, M.Z. Attitude towards Sustainable Entrepreneurship among Students: Testing a Measurement Scale. In Business and Management, Proceedings of the 12th International Scientific Conference “Business and Management 2022”, Vilnius, Lithuania, 12–13 May 2022; Vilnius Gediminas Technical University (VILNIUS TECH) Press: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2022; ISBN 978-609-476-288-8. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment. In Proceedings of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm, Sweden, 5–16 June 1972. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; UNEP. Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment. In Proceedings of the UNESCO–UNEP International Workshop on Environmental Education, Belgrade, Serbia, 13–22 October 1975. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO; UNEP. Final Report. In Proceedings of the Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education Organized by UNESCO in Cooperation with UNEP, Tbilisi, Georgia, 14–26 October 1977; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; ISBN 9780192820808. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Division for Sustainable Development. United Nations Conference on Environment & Development, Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992; United Nations Division for Sustainable Development: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development: Johannesburg, South Africa, 26 August–4 September 2002; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2002. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/478154 (accessed on 8 February 2022).

- UNESCO. The UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD 2005–2014): International Implementation Scheme. Available online: https://www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/a33_unesco_international_implementation_scheme.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- United Nations. Goal 4: Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2017/Goal-04/#:~:text=Goal%204%3A%20Ensure%20inclusive%20and%20equitable%20quality%20education,individuals%20and%20to%20the%20realization%20of%20sustainable%20development (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Talloires Declaration—ULSF. Available online: http://ulsf.org/talloires-declaration/ (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Administrator. Background. Available online: https://www.copernicus-alliance.org/background (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- IAU—International Association of Universities. Torino Declaration on Education and Research for Sustainable and Responsible Development; IAU: Torino, Italy, 2009; Available online: https://www.iau-hesd.net/sites/default/files/documents/g8torino_declaration.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Shephard, K. Higher education’s role in ‘education for sustainability’. Aust. Univ. Rev. 2010, 52, 13–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bekessy, S.A.; Samson, K.; Clarkson, R.E. The failure of non-binding declarations to achieve university sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azapagic, A.; Perdan, S.; Shallcross, D. How much do engineering students know about sustainable development? The findings of an international survey and possible implications for the engineering curriculum. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 30, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmasin, M.; Voci, D. The role of sustainability in media and communication studies’ curricula throughout Europe. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 42–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quist, J.; Rammelt, C.; Overschie, M.; de Werk, G. Backcasting for sustainability in engineering education: The case of Delft University of Technology. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaff, E.; Ravesteijn, W. Training complete engineers: Global enterprise and engineering education. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2001, 26, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, K. Engineering education in sustainable development: Sustainability as a tool to open up the windows of engineering institutions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2004, 13, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heel, H.P.; Jansen, J. Duurzaam: Zo Gezegd, zo Gedaan; Technische Universiteit Delft: Delft, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, M.; Godemann, J.; Rieckmann, M.; Stoltenberg, U. Developing key competencies for sustainable development in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambrechts, W.; Mulà, I.; Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Gaeremynck, V. The integration of competences for sustainable development in higher education: An analysis of bachelor programs in management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trencher, G.; Vincent, S.; Bahr, K.; Kudo, S.; Markham, K.; Yamanaka, Y. Evaluating core competencies development in sustainability and environmental master’s programs: An empirical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, P.; Beckett, D. Philosophical underpinnings of the integrated conception of competence. Educ. Philos. Theory 1995, 27, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturmberg, J.P.; Hinchy, J. Borderline competence—From a complexity perspective: Conceptualization and implementation for certifying examinations. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2010, 16, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, G. The development of ESD-related competencies in supportive institutional frameworks. Int. Rev. Educ. 2010, 56, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poza-Vilches, F.; López-Alcarria, A.; Mazuecos-Ciarra, N. A Professional Competences’ Diagnosis in Education for Sustainability: A Case Study from the Standpoint of the Education Guidance Service (EGS) in the Spanish Context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rieckmann, M. Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be fostered through university teaching and learning? Futures 2012, 44, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Barth, M.; Cebrián, G.; Cohen, M.; Diaz, L.; Doucette-Remington, S.; Dripps, W.; Habron, G.; Harré, N.; Jarchow, M.; et al. Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—Toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Barreiro-Gen, M.; Pietikäinen, J.; Gago-Cortes, C.; Favi, C.; Jimenez Munguia, M.T.; Monus, F.; Simão, J.; Benayas, J.; Desha, C.; et al. Adopting sustainability competence-based education in academic disciplines: Insights from 13 higher education institutions. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Merrill, M.; Sammalisto, K.; Ceulemans, K.; Lozano, F. Connecting Competences and Pedagogical Approaches for Sustainable Development in Higher Education: A Literature Review and Framework Proposal. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mulà, I.; Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M. Lessons Learned and Future Research Directions in Educating for Sustainability Competencies. In Competences in Education for Sustainable Development: Critical Perspectives; Vare, P., Lausselet, N., Rieckmann, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 185–194. ISBN 978-3-030-91055-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, S.; Scott, W. Sustainable Development and Learning: Framing the Issues, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 9780415276481. [Google Scholar]

- CSCT. Competencies for ESD (Education for Sustainable Development) Teachers: A Framework to Integrate ESD in the Curriculum of Teacher Training Institutes; Sleurs, W., Ed.; CSCT: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, F.; Steiner, R. Competences for Education for Sustainable Development in Teacher Education. CEPSj 2013, 3, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, B.; Walczyna, A.; Bojar, M. Structure of Competences of Lublin University of Technology Students in the Field of Sustainable Development. ERSJ 2021, XXIV, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrián Bernat, G.; Junyent Pubill, M. Competencias profesionales en Educación para la Sostenibilidad: Un estudio exploratorio de la visión de futuros maestros. Ensciencias 2014, 32, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bertschy, F.; Künzli, C.; Lehmann, M. Teachers’ Competencies for the Implementation of Educational Offers in the Field of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2013, 5, 5067–5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charrad, M.; Ghazzali, N.; Boiteau, V.; Niknafs, A. NbClust: An R Package for Determining the Relevant Number of Clusters in a Data Set. J. Stat. Soft. 2014, 61, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stanisz, A. Przystępny Kurs Statystyki: Z Zastosowaniem STATISTICA PL na Przykładach z Medycyny; StatSoft: Kraków, Poland, 2006; ISBN 978-83-88724-18-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sułkowski, Ł.; Kolasińska-Morawska, K.; Seliga, R.; Buła, P.; Morawski, P. Sustainability Culture of Polish Universities in Professionalization of Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naqbi, A.K.; Alshannag, Q. The status of education for sustainable development and sustainability knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of UAE University students. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 566–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrakis, V.; Kostoulas, M. Developing and Validating an ESD Student Competence Framework: A Tempus—Rucas Initiative. IJEE 2013, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for sustainable development (ESD): The turn away from ‘environment’ in environmental education? Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmassah, S.; Biltagy, M.; Gamal, D. Engendering sustainable development competencies in higher education: The case of Egypt. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 121959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.; Froese, T.; Nesbit, S. Canadian Civil Engineering and Sustainable Development Competence. PCEEA 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).