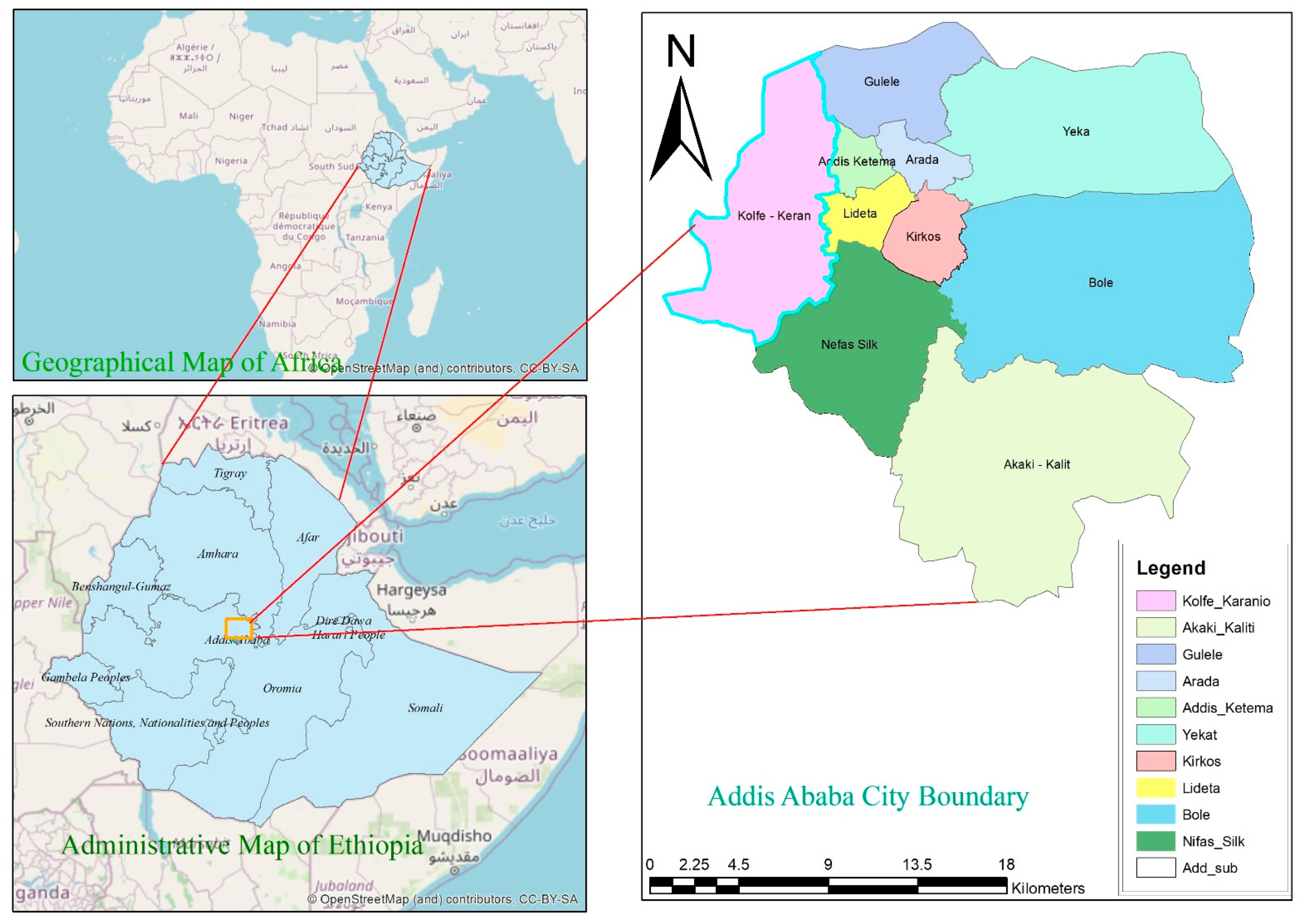

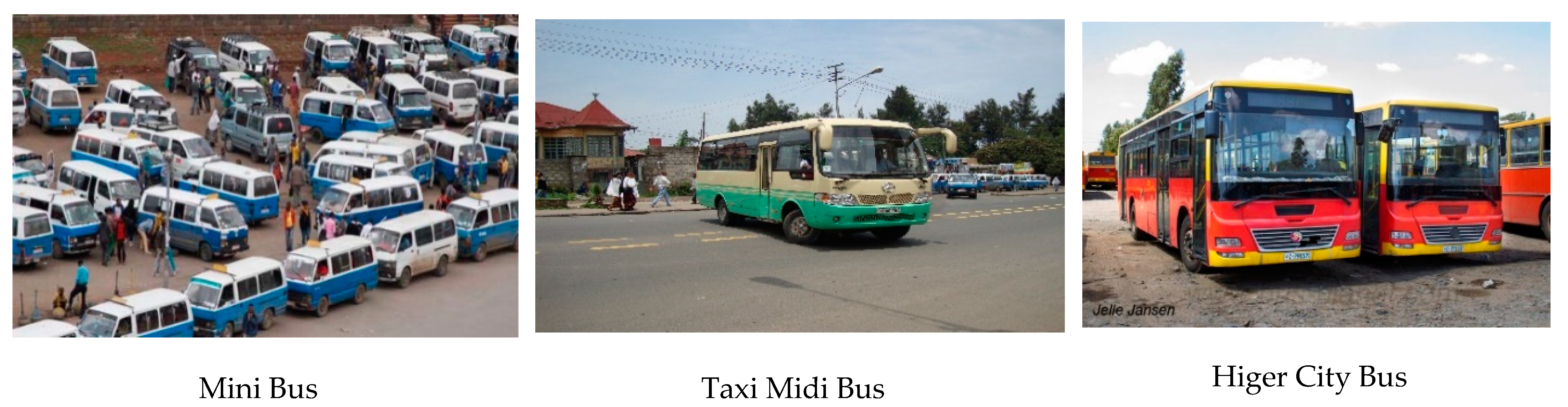

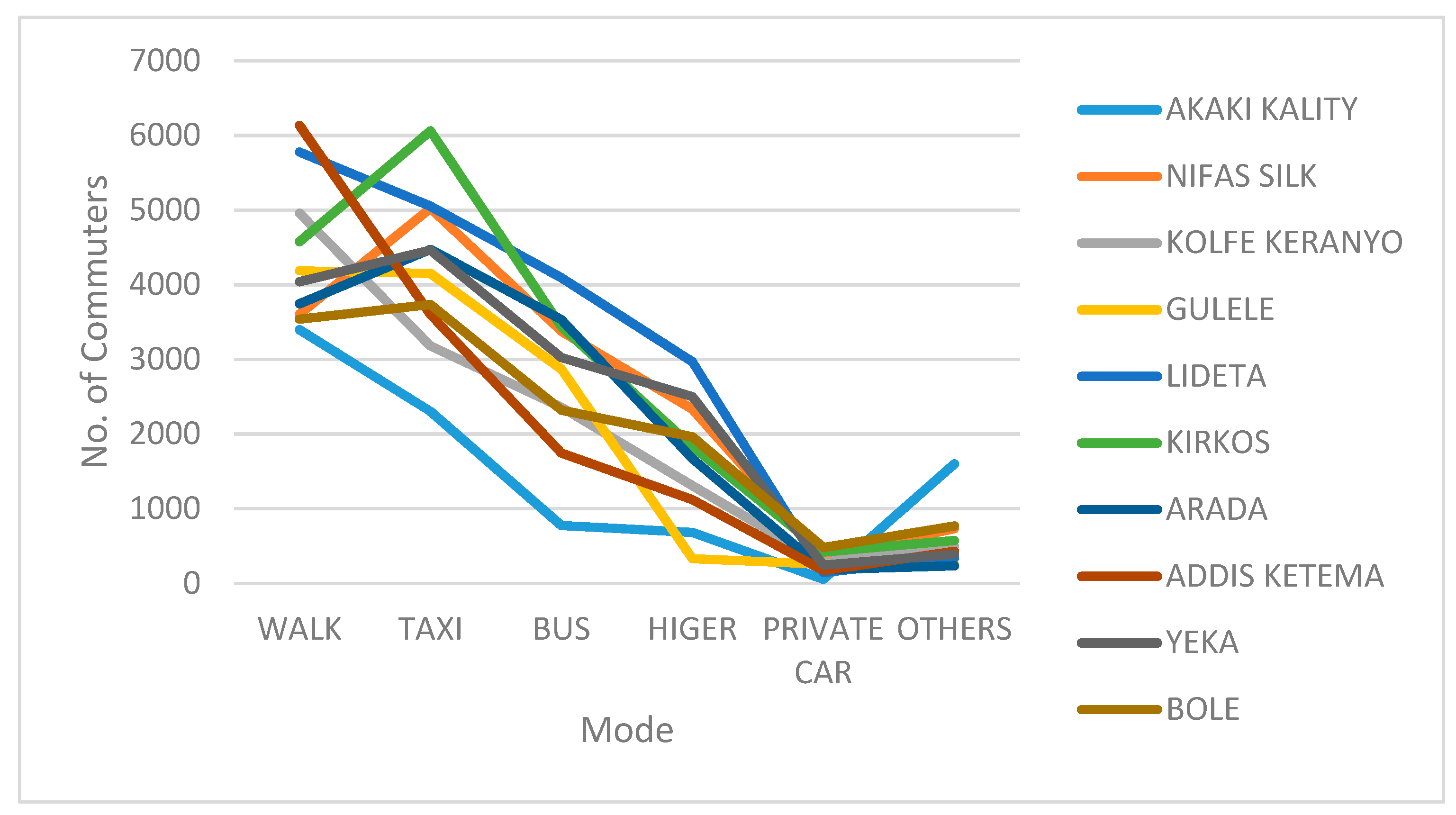

This paper addresses public transport affordability in Addis Ababa on city-wide and sub-city levels. The sub-cities are very similar in terms of overall modal share and socio-demographic and spatial characteristics; furthermore, their mobility patterns are similar to cities in other developing countries. Public transport is the most important motorized transport mode for the urban poor.

As a result, if they cannot access public transport, they must walk or be immobile. Middle-income and affluent groups, however, could complement their trips by using their car or taking a taxi. The implication is quite straightforward: in developing countries, public transport affordability is a crucial component to achieve equity.

6.1. Main Findings

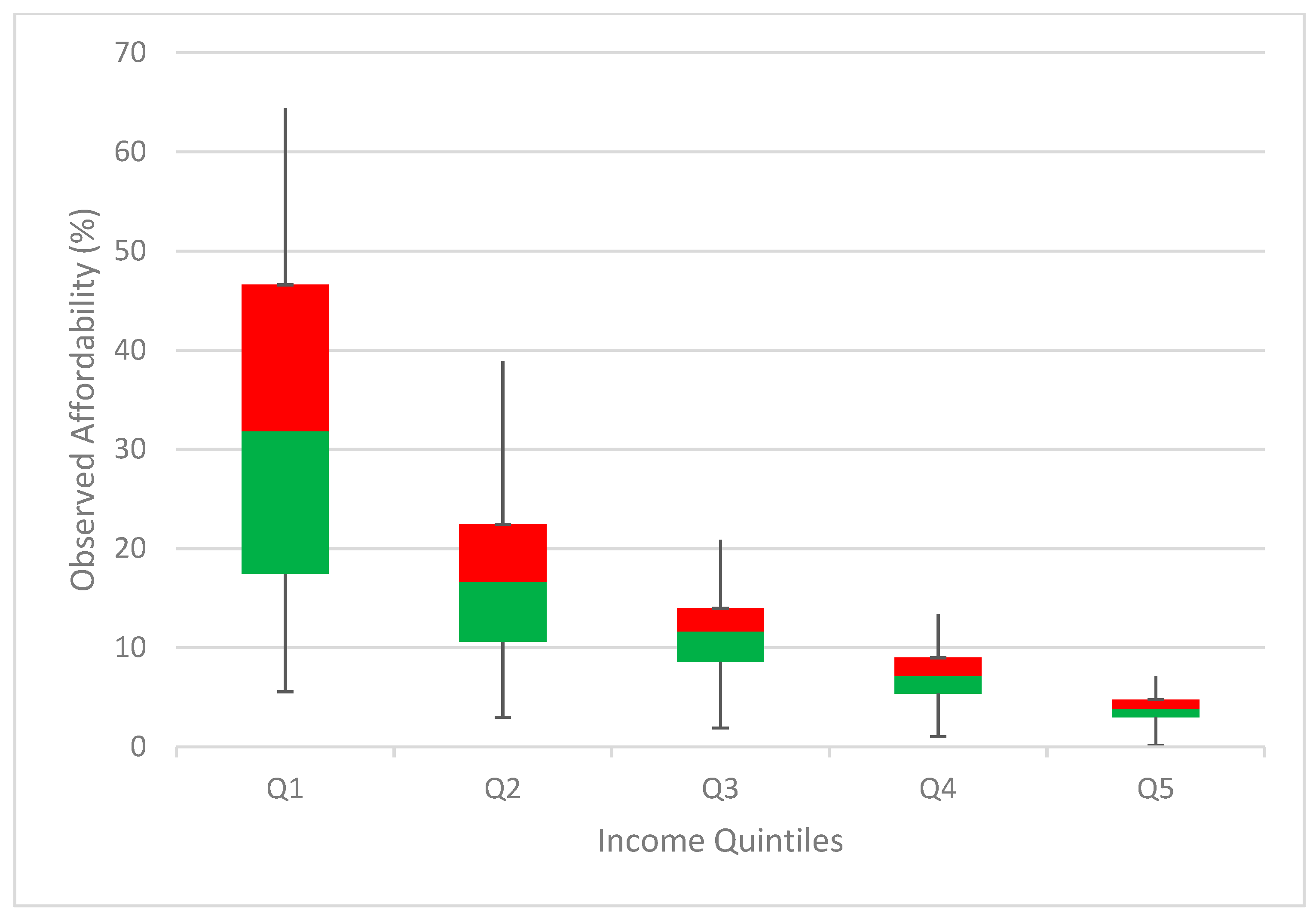

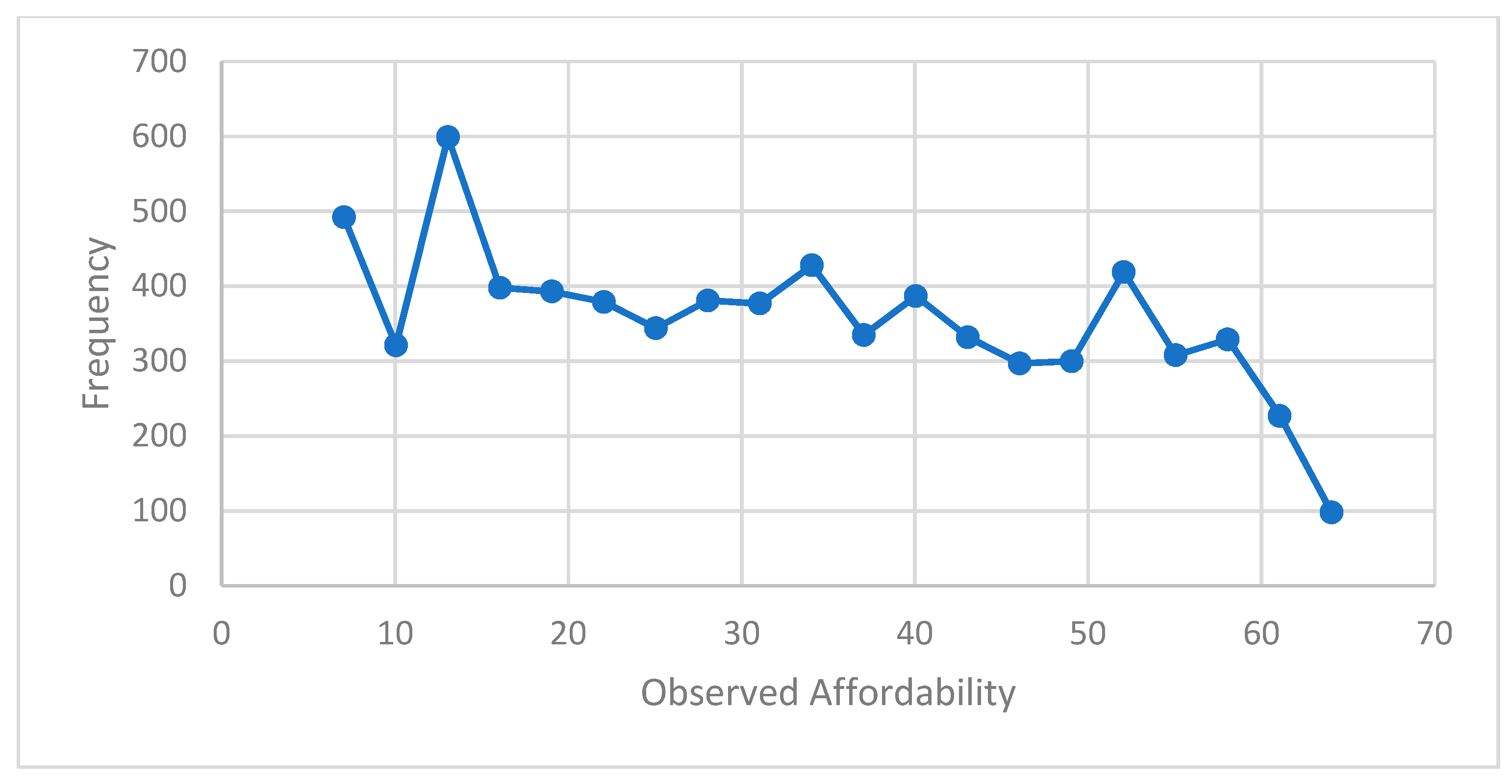

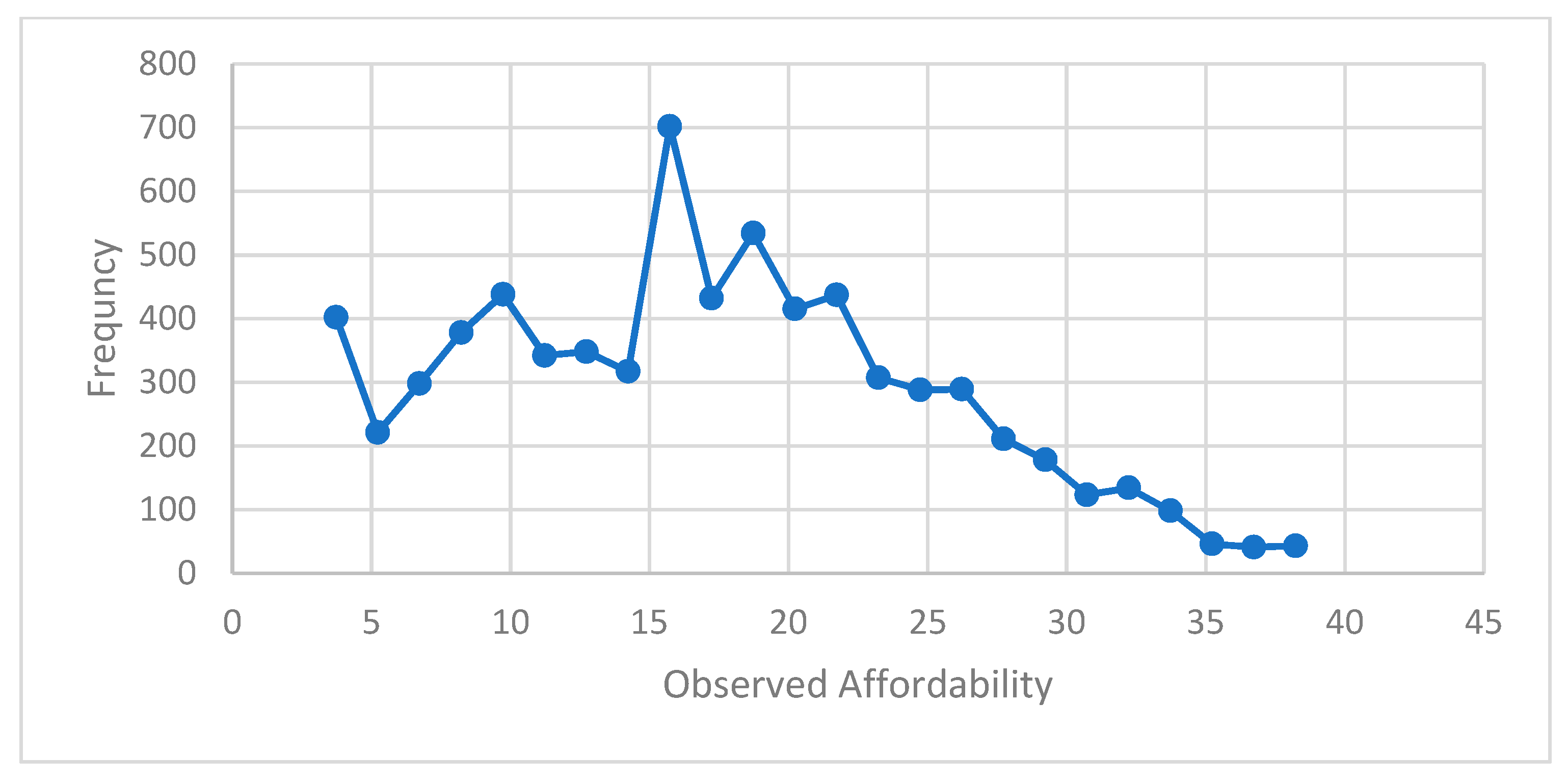

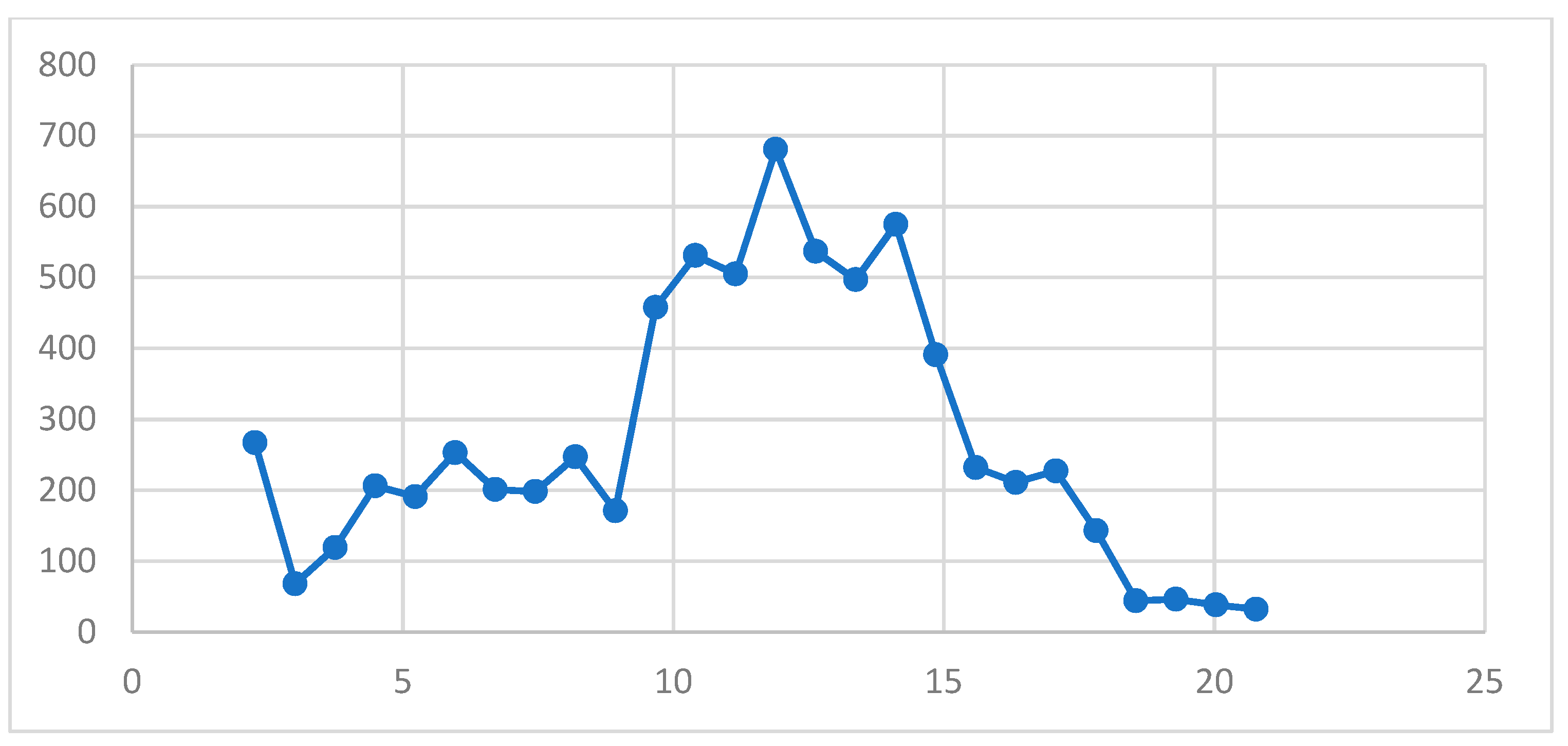

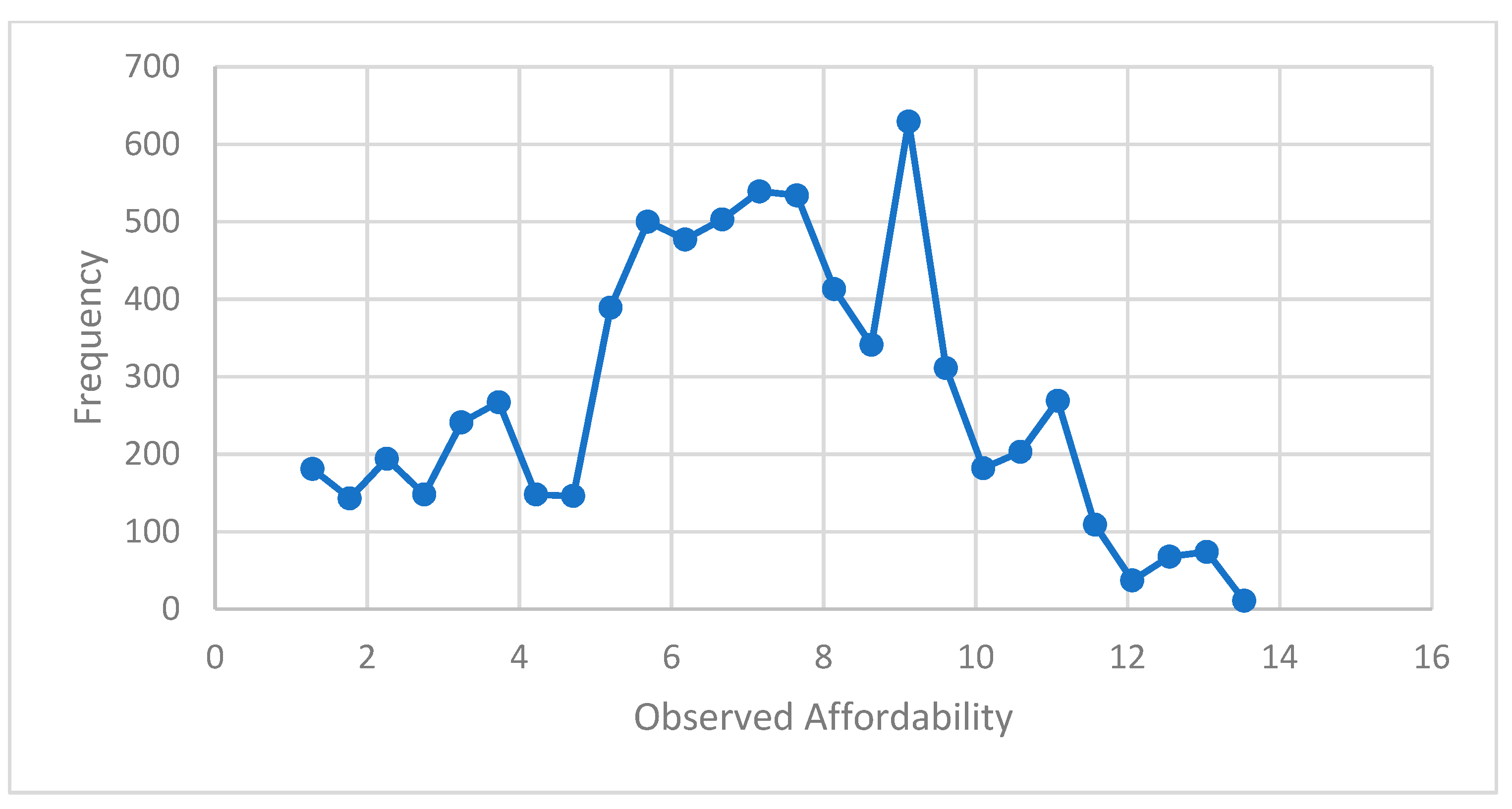

In the case of observed affordability of public transport (Affo), the actual trips of urban low-income families are not considered holistically; instead, the metric fails to consider those reduced trips. In filling this gap, the public transport potential affordability approach is an improvement to over the observed affordability approach. The potential affordability (Affp) metric assumes the middle-income class (Q3) is capable of undertaking all desired trips without compromising any of them. That means that potential affordability values are higher than the observed affordability values for lower-income classes.

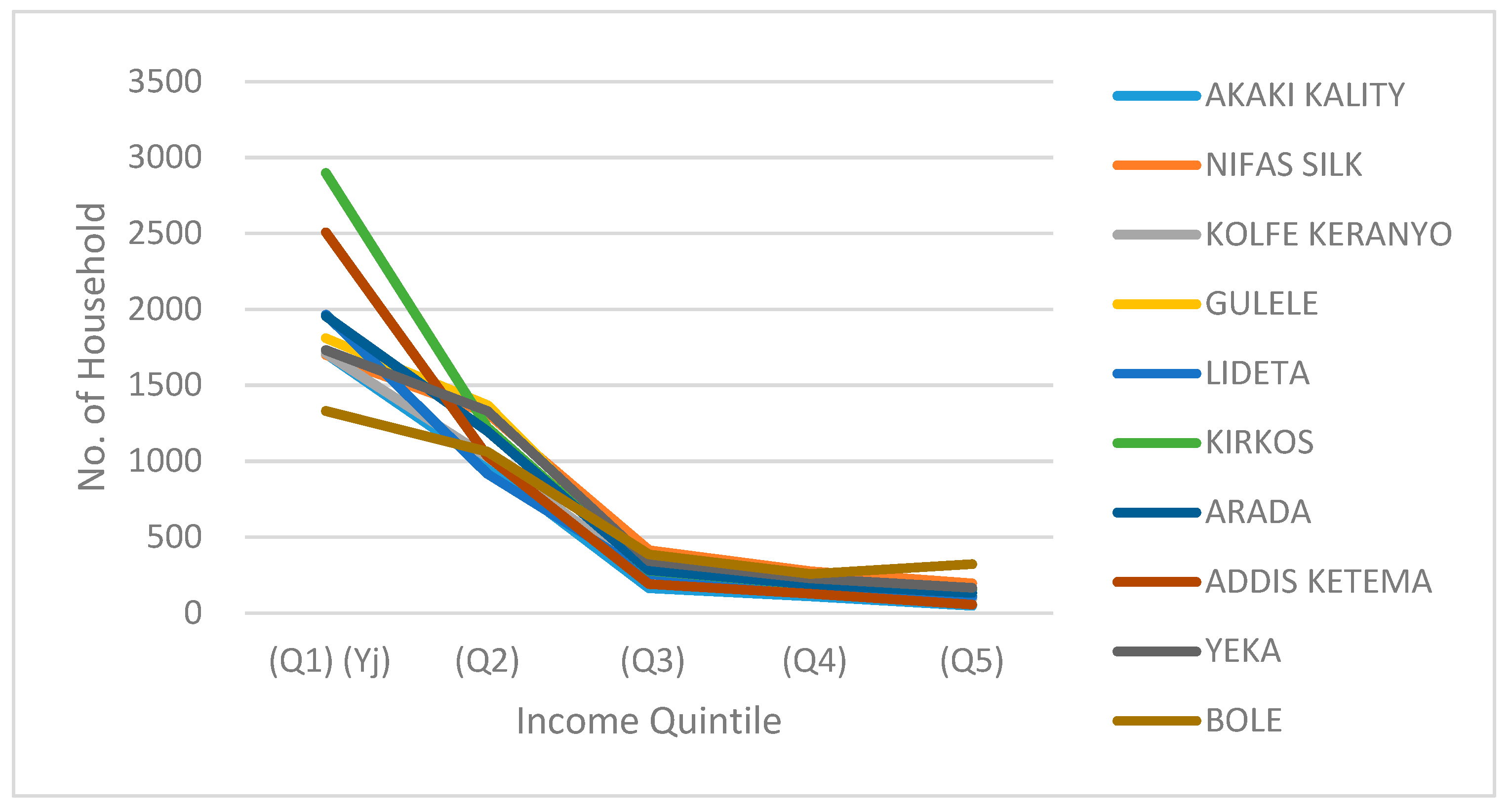

On average, the observed public transport affordability index is about 14.13% citywide (with the smallest value of 3.69 for the highest income group (Q5) and the highest value of 32.11 for the lowest income group (Q1)). On the other hand, the public transport potential affordability index is about 14.83% citywide (with 11.04 for the middle-income group (Q3) and 41.21 for the lowest income group (Q1)).

The difference between the potential and observed affordability indicates that to reach the same motorized trip rates as the third quintile, households in the lowest quintile need to increase their transport expenditure by 28.34% in Addis Ababa. This means that, if the poorest households could spend 28.34% more than they currently spend, they should not need to forego any trips.

6.2. Policy Implications

This study offers a viable approach that assists policymakers to shed light on public transit strategies. In this sense, a more realistic affordability measure provides a better policy alternative to the strategies aiming at minimizing financial burdens for mobility of the urban poor.

The variation of the two affordability indices, i.e., potential and observed, gives the insight to recognize financial equity in transport expenses that impacts mobility rates of various income classes differently. In this context, urban transport officials should target residents of the lower economic class to be able to commute a public transit trip amount equivalent to middle-income residents to combat trips sacrificed due to unaffordability.

When a particular household composition is considered in the city, the poorest 20% (Q1) should spend 28% more than the actual expenditure to equalize those public transport trip rates of the third quintile, showing that the mobility problem of the poorest is very significant.

In short, Addis Ababa’s city administrators should be attentive to their low-income residents’ lack of mobility options due to unaffordability. The results of this study clearly show that Addis Ababa is encountering dual challenges from the transport affordability perspective. On the one hand, the high degree of observed affordability index actually forces residents to allocate a significant portion of their earnings towards transport. Thus, any strategies targeting minimizing public transport flat fare through subsidies the median income may not reduce observed affordability because it does not particularly address the targeted lowest income groups. On the other hand, mobility challenges mainly affect the two lowest income classes, and thus, it might be useful to apply strategies, through targeted discounts and subsidies that reduce transit fares relative to wages to minimize avoided trips, among the bottom quintile groups.

In general, the findings of this study can be generalized in a broader context towards public transportation improvement in Africa in general and those cities with similar land use policies, mobility characteristics, population sizes, and income distributions in particular. This can help urban transport policy makers in this region to give due attention in dealing with transport equity based on income rather than simply employing subsidies based on median income. The following are lists of available strategies to enhance transportation affordability: address security concerns, bike-transit integration, commuter financial incentives, commute trip reduction (CTR) programs, land use accessibility improvements, location-efficient development, mobility management marketing, improvements in non-motorized transport (NMT), ride sharing, school trip management, smart growth, telework, taxi service improvements, transit improvements, etc.

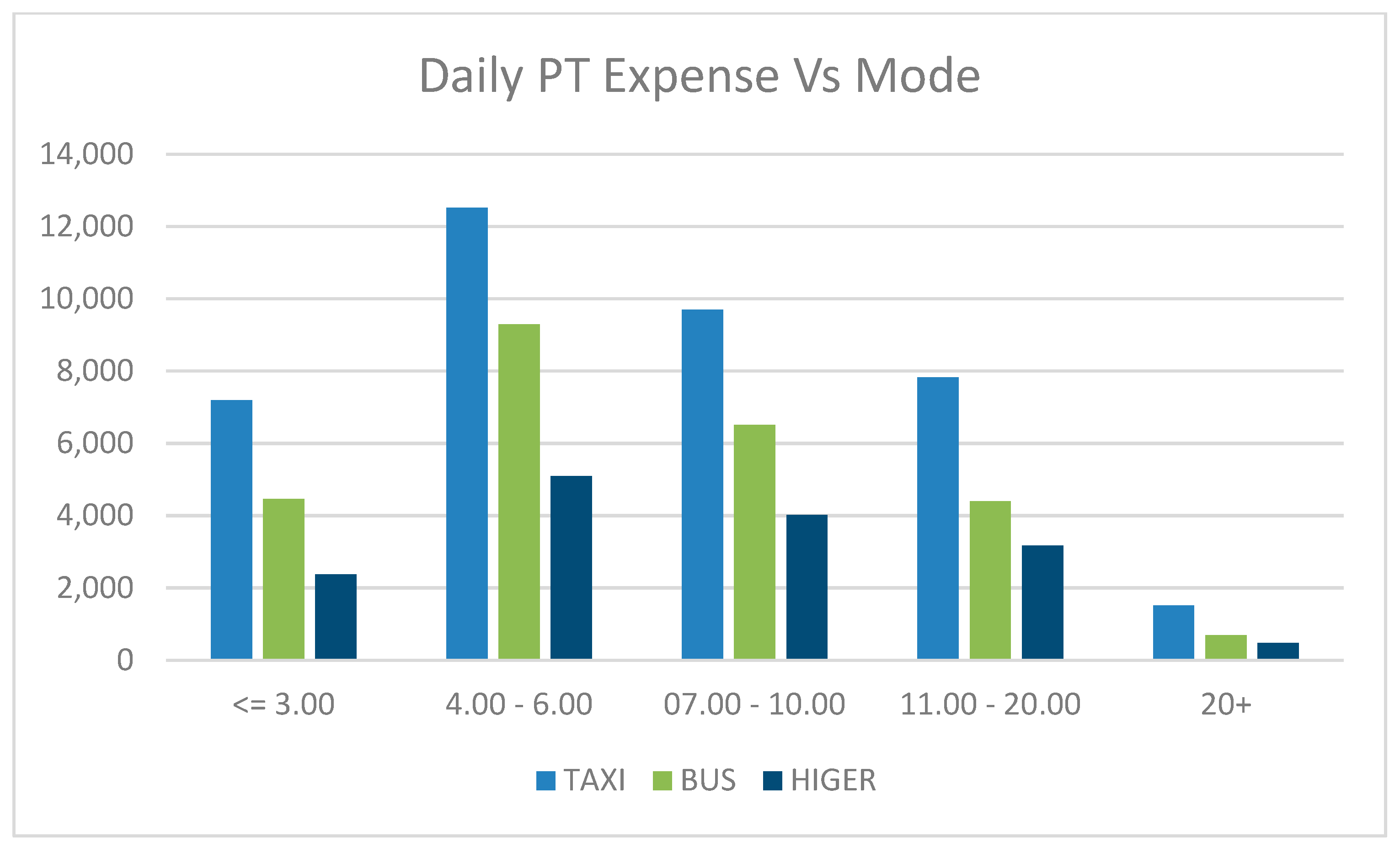

However, this study can be made more comprehensive in similar future studies if the following major limitations are addressed. First, the study is focused on affordability of bus-based public transport users only, but it can be extended to other transport modes, including private cars and rail-based transit. Second, this study is limited to public transport affordability from a transport perspective only due to data availability, whereas recent studies consider transport affordability evaluation from both a transport and housing perspective by conducting a comprehensive transport and housing survey.