Preparing Vulnerable Populations for Science Literacy and Young Adults for Global Citizenship through Service Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- check the impact of the service-learning project on the target community’s science literacy.

- assess soft skills developed by undergraduate students participating in the project.

- identify motivational factors in university students to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education) with the service-learning project.

- compare the impact of service-learning in both face-to-face and online modes.

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Focus Groups

3.2. Procedure

3.3. Quantitative Data

3.4. Qualitative Data

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Formative Assessment of Teams’ Performances

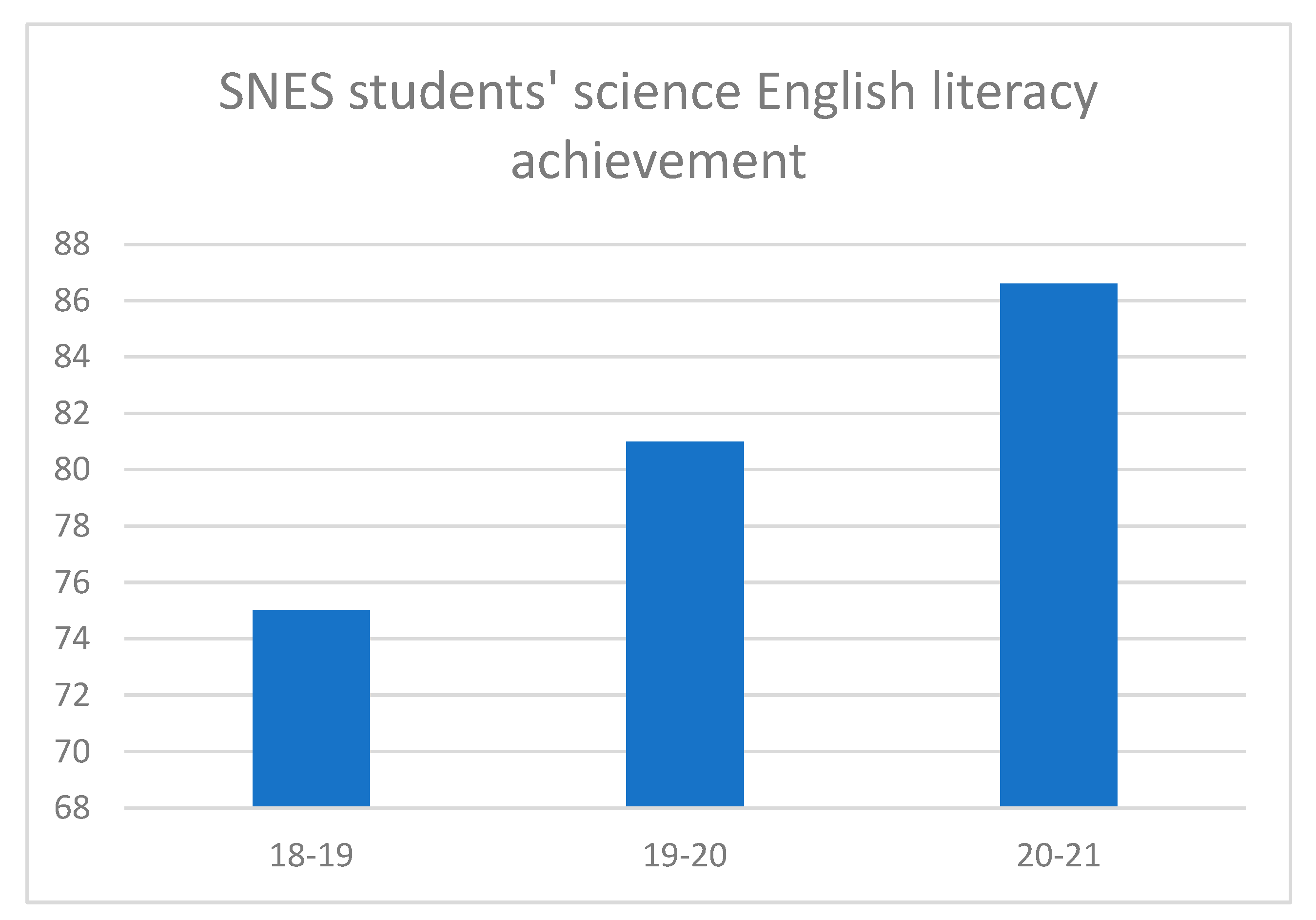

4.2. Students with SNES’ Assessment

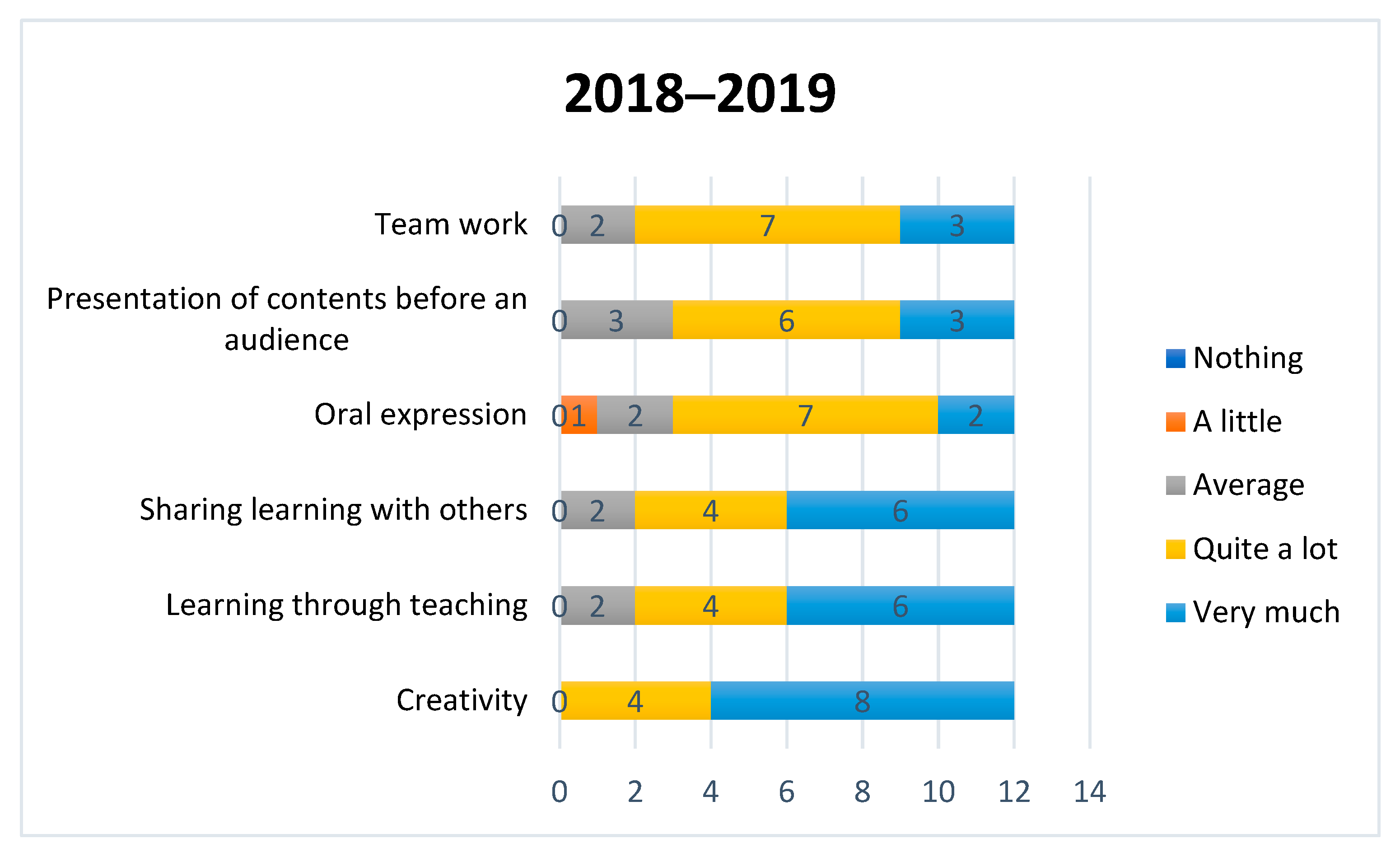

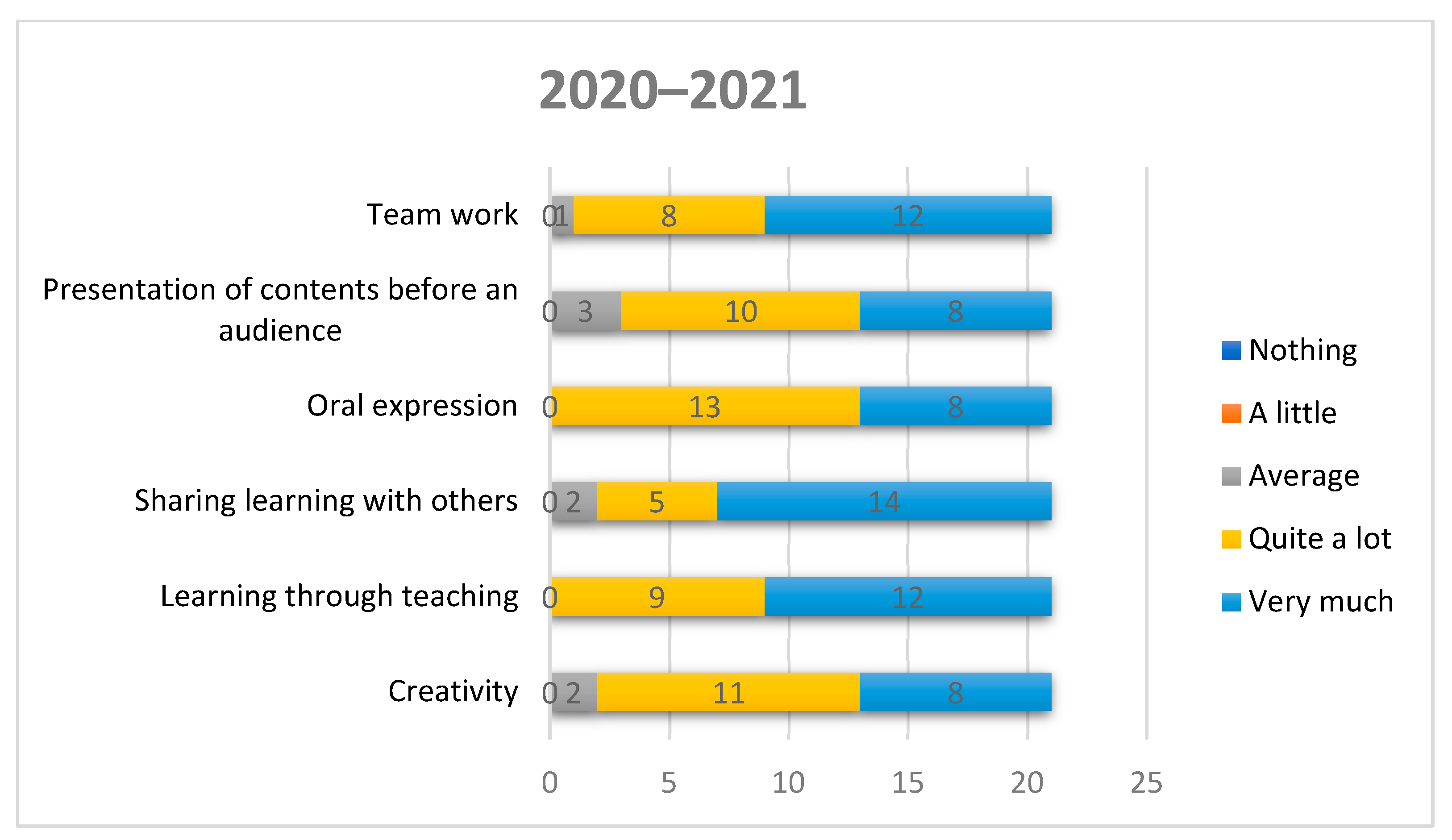

4.3. Final Survey (Close Questions)

4.3.1. Teamwork

4.3.2. Communication

4.3.3. Sharing Learning with Others

4.3.4. Learning through Teaching

4.3.5. Creativity

4.4. Situational Motivation Scale Questionnaire

4.5. Final Survey (Open Question)

4.6. Students’ Final Essay

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Domingo Moratalla, A. Responsible knowledge and active citizenship: Ethical keys of Service-Learning. In Condición humana y Ecología integral. Horizontes Educativos para una Ciudadanía Global; Publishers Publicity Circle: Madrid, Spain, 2017; p. 101. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, J.; Dominguez, L.A. Developing University and Community Partnerships: A Critical Piece of Successful Service Learning. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 2015, 44, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.; Cripps, J.; Reisman, J. Service-learning in deaf studies: Impact on the development of altruistic behaviors and social justice concern. Am. Ann. Deaf. 2013, 157, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Romero, D.; Sánchez-Busqués, S.; Lalueza, J.L. Exploring the value of Service Learning: Students’ assessments of Personal, Procedural and Content Learning. Estud. Sobre Educ. 2018, 35, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ciesielkiewicz, M.; Nocito, G.; Herrero, Y. The impact and benefits of the service-learning methodology for the Higher Education teaching personnel. Aula De Encuentro 2017, 19, 34–57. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Müller, J.V.; Ned, L.; Boshoff, H. A university’s response to people with disabilities in Worcester, Western Cape. Afr. J. Disabil. 2019, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonati, M.L. Collaborative Planning: Cooking Up an Inclusive Service-Learning Project. Educ. Treat. Child. 2018, 41, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J. Learning to Teach Students with Disabilities through Community Service-Learning: Physical Education Preservice Teachers’ Experiences. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2021, 68, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chang, S.H.; Haegele, J.A. Does Service-Learning Work? Attitudes of College Students toward individuals with disabilities. J. Exp. Educ. 2020, 43, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozencroft, A.J.; Pate, J.R.; Griffiths, H.K. Experiential learning and its impact on students’ attitudes toward youth with disabilities. J. Exp. Educ. 2015, 38, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, J.; Ruiz-Corbella, M.; Del Pozo, A. Innovation and virtual service-learning: Elements for reflection based on experience. RIDAS Rev. Iberoam. De Aprendiz. Serv. 2020, 9, 62–80. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, N.; Giles, D.E., Jr. Where is the community in service-learning research? Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 2000, 7, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, A.; Holland, B.; Gelmon, S.; Kerrigan, S. An assessment model for service-learning: Comprehensive case studies on impact on faculty, students, community and institution. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 1996, 3, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- George-Paschal, L.; Hawkins, A.; Graybeal, L. Investigating the Overlapping Experiences and Impacts of Service-Learning: Juxtaposing Perspectives of Students, Faculty, and Community Partners. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 2019, 25, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.H.; Snell, R.S. Assessing Community Impact after Service-Learning: A Conceptual Framework. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Higher Education Advances (HEAd’20), Valencia, Spain, 2–5 June 2020; pp. 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, P.; Fitch, P. Assessing Service-Learning. Res. Pract. Assess. 2007, 2, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Aramburuzabala, P.; Gezuraga, M.; López De Arana, E. How to carry out assessment in Service-Learning projects. In Aprendizaje-Servicio: Los retos de la Evaluación; Ruiz Corbella, M., García-Gutiérrez, J., Eds.; Narcea Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 27–37. ISBN 9788427725317. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Puig, J.M.; Martín, X.; Rubio, L. How to assess service-learning projects? Voces Educ. 2017, 2, 122–132. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Alcón, A.I.; Gómez Pérez, M.N.; Elvira Zorzo, M. Formative Assessment in university service-learning projects: A diachronic study. Infanc. Educ. Y Aprendiz. 2019, 5, 26–33. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgueiras Bertomeu, P.; Luna González, E.; Puig Latorre, G. Service-Learning: A study on university students’ level of satisfaction. Rev. Educ. 2013, 362, 159–185. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, A.J.; Christensen, R.K. First-Year Student Motivations for Service-Learning: An Application of the Volunteer Functions Inventory. Mich. J. Community Serv. Learn. 2017, 23, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzak, K.; Paterson, K. Learning Through Service: Student Motivations. In Proceedings of the 2011 North Midwest Section Conference, University of Minnesota, Duluth, MN, USA, 22 June 2011; pp. 91–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jouannet, C.; Salas, M.; Contreras, M. Implementation model of service-learning at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. An experience that positively impacts integral professional formation. Calid. Educ. 2013, 39, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalge, S.; Pajunen, M.; Brotherton, J. Service-Learning makes it real: Assessing value and relevance in Anthropology education. Ann. Anthropol. Pract. 2018, 42, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunti, C.; Chipa, S.; Orlandini, L. The impact of service learning in teaching-learning practices. In Proceedings of the 12th annual International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation (ICERI 2019), Seville, Spain, 11–13 November 2019; pp. 4506–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielkiewicz, M.; Nocito, G. Motivation in service-learning: An improvement over traditional instructional methods. Teknokultura 2018, 15, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersz, D.; Olaru, D. The value of service-learning: The student perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 42, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Álvarez, C.; Silió Sáiz, G. Service-learning and learning communities: Two innovative school projects that are mutually enriched. Enseñanza Teach. 2015, 33, 43–58. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, J.A. Bridging the Gap with Voice and Movement. Exp. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. (ELTHE) A J. Engaged Educ. 2020, 3, 3–6. Available online: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/elthe/vol3/iss1/6 (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Doody, K.R.; Schuetze, P.; Fulcher, K. Service Learning in the Time of COVID-19. Exp. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 2020, 3, 12–16. Available online: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/elthe/vol3/iss1/8/ (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Bradford, M. Motivating students through project-based service learning. Technol. Horiz. Educ. 2005, 32, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Turchyn, I. The importance of soft skills in educational process. Int. Sci. J. Grail Sci. 2021, 5, 291–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.K.; Wiczer, E.; Eberhardt, N.B. What’s so hard about soft skills? Am. Speech-Lang. Hear. Assoc. ASHA Lead. 2019, 24, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, K.; Baker, H.; Mascorro, A. Service-Learning in a Pandemic: The Transition to Virtual Engagement. J. Nurs. Educ. 2021, 60, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherk, J.; Bretzman, D. Integrating service-learning in a landscape design/build course in a hybrid and an online format. In Proceedings of the 13th Annual International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies (EDULEARN 21), Mallorca, Spain, 5–6 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Veyvoda, M.A.; Van Cleave, T.J. Re-Imagining Community-Engaged Learning: Service-Learning in Communication Sciences and Disorders Courses During and After COVID-19. Perspectives 2020, 5, 1542–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovi, K.; Chiarelly, J.; Franco, J. Service-Learning for a Multiple Learning Modality Environment. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98, 2005–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.A.; Schönemann, N.; Karpa, D. Integrating Service-Learning into the University Classroom; Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- Guay, F.; Vallerand, R.; Blanchard, C. On the Assessment of Situational Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: The Situational Motivation Scale (SIMS). Motiv. Emot. 2000, 24, 175–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Varela, J.L.; Gregori-Giralt, E. The reliability and sources of error of using rubrics-based assessment for student projects. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escofet, A. Service-learning and digital technologies: A possible relationship? RIED Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Distancia 2020, 23, 169–182. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Nichols, H. A reflexive evaluation of technology-enhanced learning. Res. Learn. Technol. 2017, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, M.Y.; Lee, A.; Wong, M.L.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, V.; Li, J.; Ng, E.N.E. Pilot study: Impacts of a telephone-based service-learning program on undergraduate students in Hong Kong. In Proceedings of the 13th Annual International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies (EDULEARN 21), Mallorca, Spain, 5–6 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Playford, D.; Bailey, S.; Fisher, C.; Stasinska, A.; Marshall, L.; Gawlinski, M.; Young, S. Twelve tips for implementing effective service learning. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Wilder, C.; Yu, C. Exploring students’ perceptions of service-learning experiences in an undergraduate web design course. Teach. High. Educ. 2018, 23, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, L.; Maloney, P.; Karp, T. Self-Efficacy Development among Students Enrolled in an Engineering Service-Learning Section. Int. J. Serv. Learn. Eng. Humanit. Eng. Soc. Entrep. 2018, 13, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnell, M.; Daniels, M.; Hallinan, K.; Berkemeier, G. Leveraging Students’ Passion and Creativity: ETHOS at the University of Dayton. Int. J. Serv. Learn. Eng. 2014, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Kim, M.S.; Hwang, H.; Lee, B.Y. Effects of intrinsic motivation and informative feedback in service-learning on the development of college students’ life purpose. J. Moral Educ. 2018, 47, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folgueiras, P.; Guezuraga, M.; Aramburuzabala Higuera, P. Participatory processes in service-learning. Bordón Rev. Pedagog. 2019, 71, 97–114. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque-Bristol, C.; Knapp, T.D.; Fisher, B.J. The effectiveness of Service-Learning: It’s not always what you think. J. Exp. Educ. 2010, 33, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, A.; Longmire-Avital, B.; Chenault, J.; Haglund, M. Students’ Motivation in Academic Service-Learning over the course of the semester. Coll. Stud. J. 2013, 47, 185–191. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=trh&AN=92757396&site=ehost-live (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Jones, J.L.; Gallus, K.L.; Cothern, A.S. Breaking Down Barriers to Community Inclusion Through Service-Learning: A Qualitative Exploration. Inclusion 2016, 4, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n Engineering students | 12 | 17 | 7 |

| n Education students | - | 2 | 14 |

| Total n participating students | 12 | 19 | 21 |

| n teams | 4 | 8 | 8 |

| Assessment Components | Max. |

|---|---|

| Team’s participation in the session preparation | 10 |

| Team’s participation in the presentation | 10 |

| Digital resources used | 10 |

| Structure and sequencing of activities | 10 |

| Materials selected for SNES students | 10 |

| Adaptation to SNES students’ level and pace during the class | 10 |

| Interaction with SNES students | 10 |

| Ability to motivate SNES students | 10 |

| Gestures, facial expression | 10 |

| Time control | 10 |

| Total score | 100 |

| Close Questions | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Would you repeat this SL experience? | Yes | 100% | Yes | 100% | Yes | 100% |

| No | - | No | - | No | - | |

| Would you recommend it to other students? | Yes | 100% | Yes | 100% | Yes | 100% |

| No | - | No | - | No | - | |

| Would you repeat it even if it did not count for your final grade? | Yes | 92% | Yes | 90% | Yes | 100% |

| No | 8% | No | 10% | No | - | |

| Factors | Activity Motivation | Total Range: 12–84 | Mean | Median (Me) | Mode (M) | (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic | It is interesting | 69 | 9.85 | 6 | 6 | 1.58 |

| It is pleasant | 73 | 6.08 | 6 | 6 | 0.86 | |

| It is fun | 68 | 5.67 | 6 | 6 | 0.94 | |

| It makes one feel good | 72 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1.35 | |

| Identified Regulation | It is for one’s own good | 56 | 4.66 | 4.5 | 4 | 1.54 |

| It is good for oneself | 75 | 6.25 | 6 | 6 | 0.82 | |

| By personal decision | 78 | 6.5 | 7 | 7 | 0.65 | |

| It is important for oneself | 72 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0.82 | |

| External Regulation | One is supposed to do it | 31 | 2.58 | 2 | 1 | 1.89 |

| It is one’s obligation | 20 | 1.67 | 1 | 1 | 1.37 | |

| There is no choice | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| One feels that has to do it | 66 | 5.5 | 6 | 6 | 0.96 | |

| Amotivation | One cannot see any reason | 17 | 1.41 | 1 | 1 | 0.86 |

| Not sure it is worth it | 16 | 1.33 | 1 | 1 | 0.85 | |

| One cannot see any utility | 15 | 1.25 | 1 | 1 | 0.82 | |

| Not sure if it is a good thing | 14 | 1.17 | 1 | 1 | 0.55 |

| Factors | Activity Motivation | Total Score Range: 19–33 | Mean | Median (Me) | Mode (M) | (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic | It is interesting | 113 | 5.94 | 6 | 6 | 0.94 |

| It is pleasant | 113 | 5.94 | 6 | 6 | 0.88 | |

| It is fun | 102 | 5.36 | 6 | 6 | 1.49 | |

| It makes one feel good | 121 | 6.36 | 6 | 7 | 0.66 | |

| Identified Regulation | It is for one’s own good | 93 | 4.89 | 5 | 6 | 1.33 |

| It is good for oneself | 111 | 5.84 | 6 | 6 | 0.87 | |

| By personal decision | 117 | 6.15 | 7 | 7 | 1.08 | |

| It is important for oneself | 104 | 5.47 | 6 | 6 | 1.5 | |

| External Regulation | One is supposed to do it | 47 | 2.47 | 1 | 1 | 1.95 |

| It is one’s obligation | 46 | 2.42 | 1 | 1 | 1.87 | |

| There is no choice | 27 | 1.42 | 1 | 1 | 0.81 | |

| One feels that has to do it | 85 | 4.4 | 5 | 7 | 2.20 | |

| Amotivation | One cannot see any reason | 37 | 1.94 | 1 | 1 | 1.76 |

| Not sure it is worth it | 32 | 1.68 | 1 | 1 | 1.29 | |

| One cannot see any utility | 21 | 1.10 | 1 | 1 | 0.30 | |

| Not sure if it is a good thing | 21 | 1.10 | 1 | 1 | 0.30 |

| Factors | Activity Motivation | Total Score Range: 21–147 | Mean | Median (Me) | Mode (M) | (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsic | It is interesting | 135 | 12.2 | 7 | 7 | 0.7 |

| It is pleasant | 131 | 11.9 | 7 | 7 | 1 | |

| It is fun | 103 | 9.3 | 5 | 5 | 1.7 | |

| It makes one feel good | 126 | 11.4 | 6 | 7 | 1.1 | |

| Identified Regulation | It is for one’s own good | 100 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 1.7 |

| It is good for oneself | 126 | 11.4 | 6 | 6 | 0.9 | |

| By personal decision | 134 | 12.1 | 7 | 7 | 0.8 | |

| It is important for oneself | 127 | 11.5 | 6 | 7 | 0.9 | |

| External Regulation | One is supposed to do it | 57 | 5.1 | 1 | 1 | 2.2 |

| It is one’s obligation | 62 | 5.6 | 2 | 1 | 2.3 | |

| There is no choice | 41 | 3.7 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| One feels that has to do it | 106 | 9.6 | 6 | 7 | 2 | |

| Amotivation | One cannot see any reason | 41 | 3.7 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Not sure it is worth it | 46 | 4.1 | 1 | 1 | 2.3 | |

| One cannot see any utility | 40 | 3.6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Not sure if it is a good thing | 42 | 3.8 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Topic | Comments |

|---|---|

| Personal satisfaction | It was highly rewarding both personally and professionally. Everyone should have the opportunity to experience it. Time flew. I wished it had last longer. You feel really good. A wonderful experience I strongly recommend. An amazing experience that I would love to repeat and I undoubtedly recommend. Teaching and helping students with disabilities made me feel good. A highly satisfying experience. We received more than we gave. A great personal experience. The best experience I have had in this semester. It has been a highly satisfying experience. I have been able to experience the value of a well done job, a job put at the service of others without seeking individual recognition. |

| Interpersonal relationships | You can approach and interact with these people. I would have loved to live this experience face-to-face, but technology worked fine. It was the first time I could interact with people like these and I loved helping them. It has been a plasure to help them. They are great people. It is a shame that we could not interact face-to-face, but even so I would love to repeat it. I have loved participating in this project, I have been very comfortable with my classmates and interacting with people with disabilities. Getting closer to them has been a mutual learning. I totally recommend the experience. |

| Target community’s response | To see how they learn and have fun is very satisfying. I have learnt a lot from the people that wanted to learn a bit of English from my classmates and me. It is great to see how these students enjoy the activities we prepare for them. It was incredible to see the effort they make and the desire they have to continue learning despite their difficulties. I have learnt that if you make people happy, you will be happier. |

| Expectations | It far surpassed all my expectations. It is a great project. It was worth spending time on this activity. I feel fortunate to have had this opportunity to work on this service-learning project. |

| Teamwork | Working collaboratively with my classmates was great. We helped one another. We learnt how to work together as a team. |

| Students’ Recurrent Ideas in Final Essay | 2018–2019 | 2019–2020 | 2020–2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impact of the target community’s attitude towards servers | 55.5% | 46% | 4.7% |

| Impact of the target community’s gratefulness | 11% | 7.6% | - |

| Impact of the target community’s attitude towards learning | 66.6% | 77% | 9.5% |

| Empathy | 66.6% | 46% | 71.4% |

| Development of soft skills | 55.5% | 61.5% | 33.3% |

| Development of human values | 44.4% | 38.4% | 100% 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muñoz-Alcón, A.I.; Tejedor-Hernández, V.; Lafuente-Nafría, M.B. Preparing Vulnerable Populations for Science Literacy and Young Adults for Global Citizenship through Service Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116775

Muñoz-Alcón AI, Tejedor-Hernández V, Lafuente-Nafría MB. Preparing Vulnerable Populations for Science Literacy and Young Adults for Global Citizenship through Service Learning. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116775

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuñoz-Alcón, Ana Isabel, Víctor Tejedor-Hernández, and María Begoña Lafuente-Nafría. 2022. "Preparing Vulnerable Populations for Science Literacy and Young Adults for Global Citizenship through Service Learning" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116775

APA StyleMuñoz-Alcón, A. I., Tejedor-Hernández, V., & Lafuente-Nafría, M. B. (2022). Preparing Vulnerable Populations for Science Literacy and Young Adults for Global Citizenship through Service Learning. Sustainability, 14(11), 6775. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116775