Discussions between Place Branding and Territorial Brand in Regional Development—A Classification Model Proposal for a Territorial Brand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

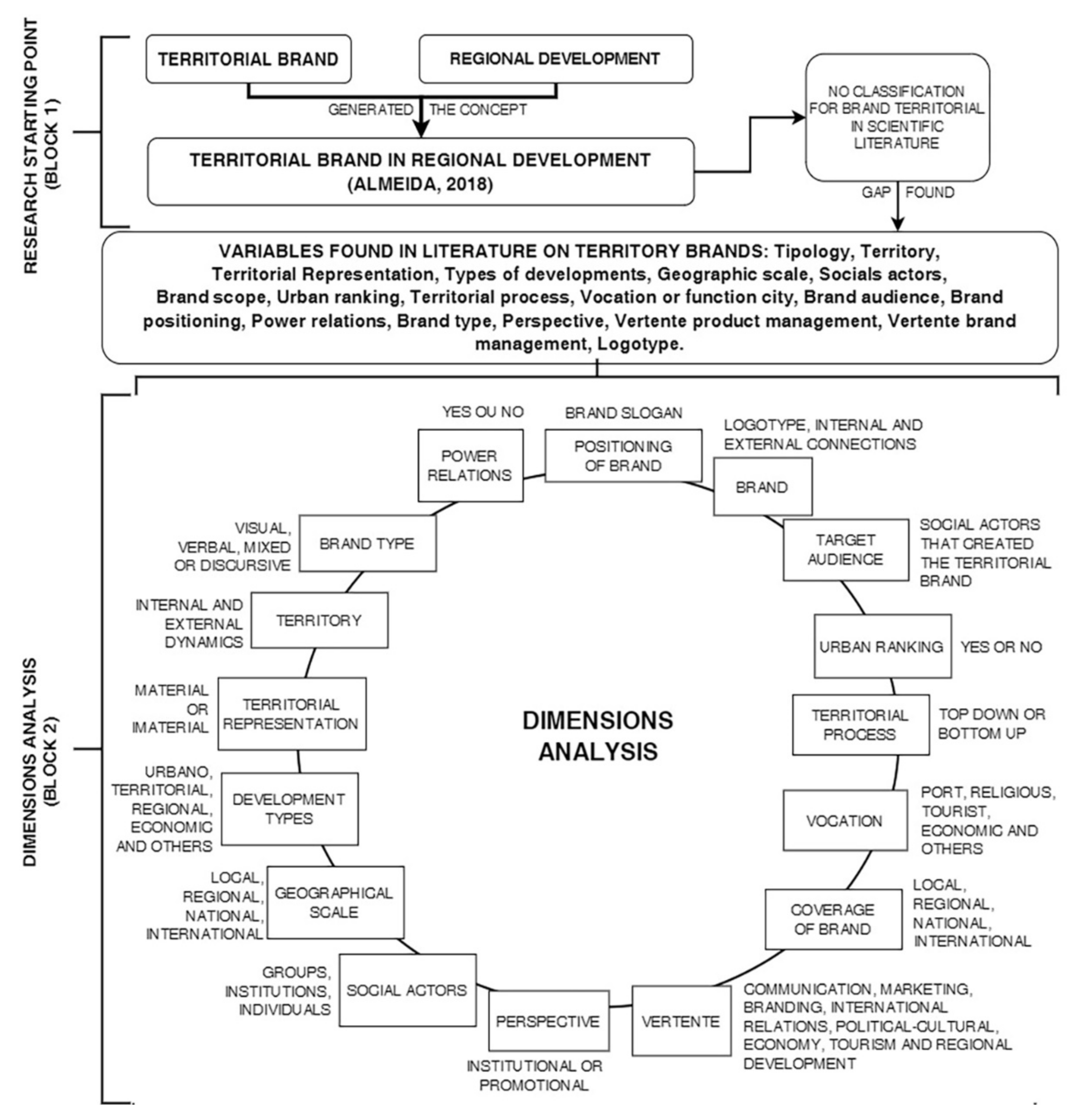

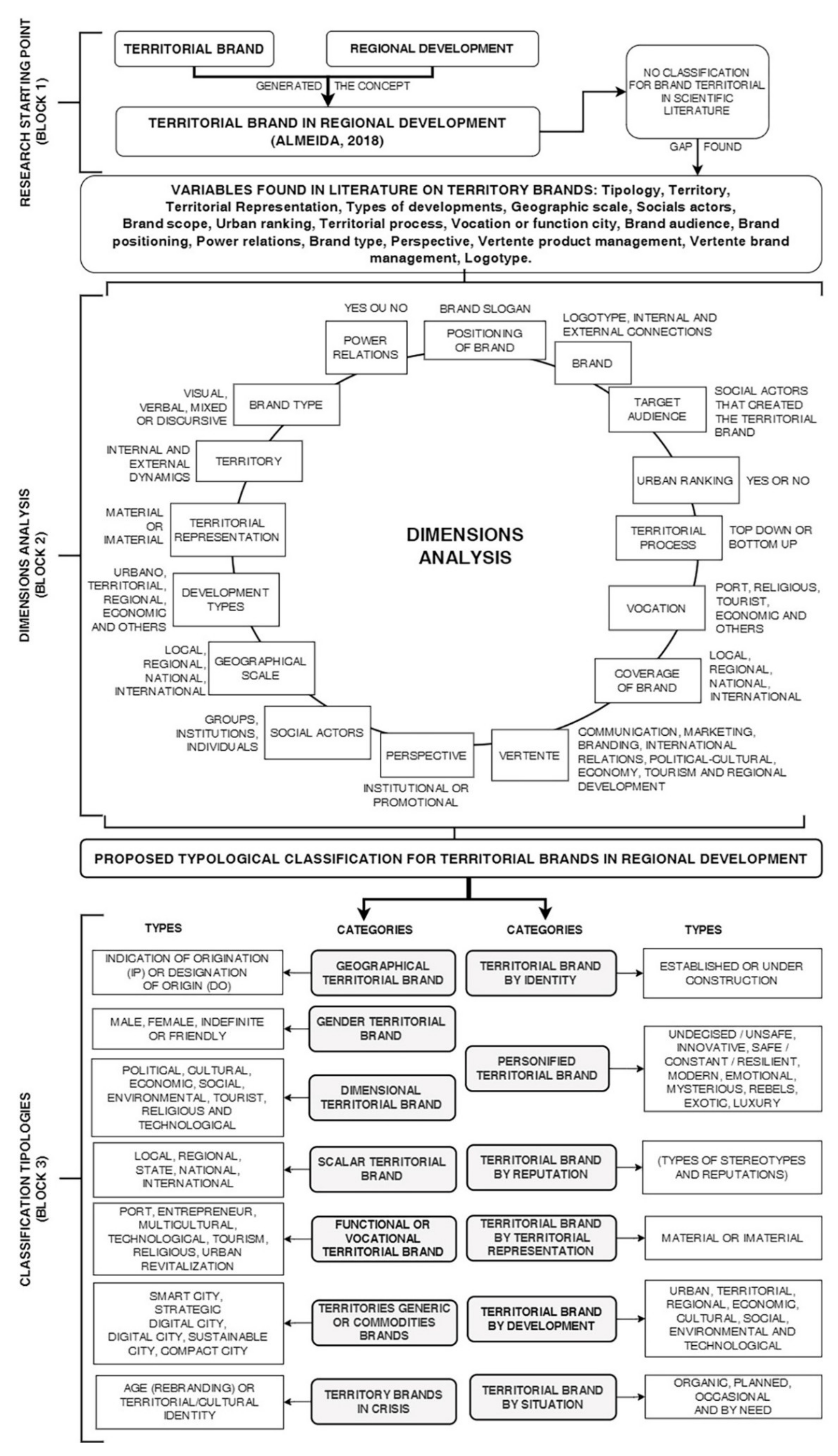

- To identify, in the scientific literature, the key concept of the territorial brand in the context of regional development;

- To identify, in the scientific literature, the variables for classifying a territorial brand in the context of regional development;

- To propose an agglutination model of the variables, analysis dimensions, and typologies for the classification of the territorial brand in the context of regional development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Place Branding and Territorial Brand

2.2. Territorial Brand in the Regional Development Context

2.3. Place Brand and Territorial Brand Typologies in the Scientific Literature

2.4. Looking for a Set of Variables to Define the Territorial Brand

2.5. Looking for a Set of Dimensions to Define the Territorial Brand

3. Materials and Methods

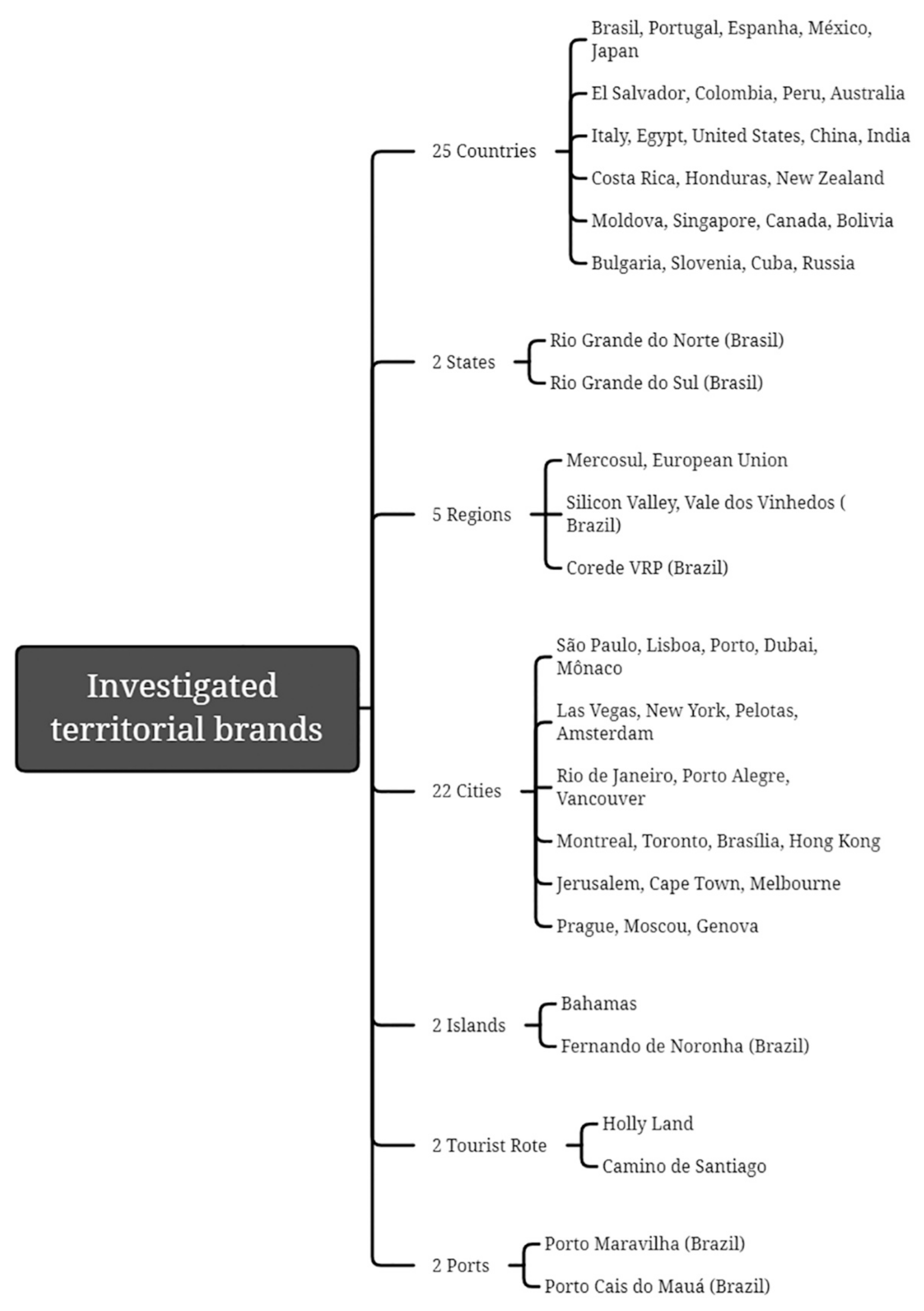

4. Results

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Findings

5.2. Research Contributions

- (1)

- Individual classification of territorial brands;

- (2)

- Overlapping classifications, where territories have more than one territorial brand;

- (3)

- Showing that territorial brands have a hegemonic classification too;

- (4)

- Showing the interests of the social actors on the territory who adopt a territorial brand;

- (5)

- Emphasizing the leading role of the territory through a territorial brand.

5.3. Research Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anholt, S. Definitions of place branding–Working towards a resolution. Place Branding Public Dipl. 2010, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almeida, G.G.F. Marca territorial como produto cultural no âmbito do Desenvolvimento Regional: O caso de Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. PhD. Thesis, University Santa Cruz do Sul, Santa Cruz do Sul, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L.; Machado, M. Gestão Estratégica de Marcas; Pearson Prentice Hall: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Haider, D.; Rein, I. Marketing Places, 1st ed.; Prentice Hall: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cidrais, A. O marketing territorial aplicado às cidades médias portuguesas: Os casos de Évora e Portalegre. Biblio3W Rev. Bibliográfica Geogr. Cienc. Soc. 2007, 6. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/b3w-306.htm (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Dinis, A. Marketing Territorial: Um Instrumento Necessário para a Competitividade das Regiões Rurais e Periféricas; Textos para Discussão-Departamento de Gestão e Economia (DGE), Universidade da Beira Interior: Covilhã, Portugal, 2004; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis, M. Place Branding: A Review of Trends and Conceptual Models; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2005; Volume 5, pp. 329–342. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Ashworth, G. Place marketing: How did we get here and where are we going? J. Place Manag. Dev. 2007, 1, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moilanen, T.; Rainisto, S. How to Brand Nations, Cities and Destinations: A Planning Book for Place Branding; Palgrave Mcmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vela, J.S.E.; Portet Ginesta, X.; Algado, S.S. De la marca comercial a la marca de território: Los casos de la doc priorat y do Montsant. Hist. Comun. Soc. 2014, 19, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.R. Marcas-lugares, bairros, cidades e nações. In Place Branding; Esteves, C., Ed.; Simonsen: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Syssner, J. Place branding from a multi-level perspective. Place Brand Public Dipl. 2010, 6, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M. A Natureza do Espaço: Técnica e Tempo, Razão e Emoção; Hucitec: São Paulo, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D. Criando e Administrando Marcas de Sucesso; Futura: São Paulo, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson, G. Rethinking the place branding construct. In Rethinking Place Branding; Kavaratzis, M., Warnaby, G., Ashworth, G.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lucarelli, A. Place branding as urban policy: The (im)political place branding. Cities 2018, 80, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertner, D. A (tentative) meta-analysis of the place marketing and place branding literature. J. Brand Manag. 2011, 19, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffestin, C. Por uma Geografia do Poder; Ática: São Paulo, Brazil, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, M. A Identidade Cultural do Território como Base de Estratégias de Desenvolvimento: Uma Visão do Estado da Arte; Projeto RIMISP: São Paulo, Santiago de Chile, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pecqueur, B. O desenvolvimento territorial: Uma nova abordagem dos processos de desenvolvimento para as economias do sul. Raízes Camp. Gd. 2005, 24, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulisova, B.; Horbel, C.; Noe, E. Rural place branding from a multi-level perspective: A Danish example. Place Branding Public Dipl. 2021, 17, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmi, J.; Bridson, K.; Casidy, R. A typology of organisational stakeholder engagement with place brand identity. J. Strateg. Mark. 2020, 28, 620–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taecharungroj, V. User-generated place brand identity: Harnessing the power of content on social media platforms. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2019, 12, 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, J.B. O Poder das Marcas; Summus Editorial: São Paulo, Brazil, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Val, M.G.C. Produção Escrita: Trabalhando com Gêneros Textuais; Ceale/FaE/UFMG: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2007; pp. 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, S. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices; Sage/The Open University: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Minayo, M.C.S. O conceito de Representações Sociais dentro da sociologia clássica. In Textos em Representações Sociais; Guareschi, P., Jovchelovitch, S., Eds.; Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 2000; pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Moscovici, S. Representações Sociais: Investigação em Psicologia Social; Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, G.G.F. A Identidade Territorial Gaúcha no Branding das Marcas Regionais: Caso da Marca da Cerveja Polar. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Santa Cruz do Sul, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, I.E. Análise Geográfica e o Problema Epistemológico da Escala; Anuário do IGEO: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992; Available online: http//www.anuario.igeo.ufrj.br/anuário_1992/vol_15_21_26.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2022).

- Sabourin, E. Desenvolvimento territorial e abordagem territorial: Conceitos, estratégias e atores. In Planejamento e Desenvolvimento dos Territórios Rurais: Conceitos, Controvérsias, Experiências; Sabourin, E., Teixeira, O.A., Eds.; Embrapa Informação Tecnológica: Brasília, Brazil, 2002; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P. Administração de Marketing, 10th ed.; Prentice Hall: São Paulo, Brazil, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, G.G.F. The role of urban rankings in the construction of perception on innovation in smart cities. Int. J. Innov. 2019, 7, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esteves, C. O Que é Place Branding. 2017. Available online: http://www.placesforus.com.br/downloads-reports-apostilas/ (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Sampaio, R. Propaganda de A a Z: Como Usar a Propaganda para Construir Marcas e Empresas de Sucesso, 3rd ed.; Campus: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ries, A.; Trout, J. Posicionamento: A Batalha pela sua Mente, 5th ed.; Pioneira: São Paulo, Brazil, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kipnis, D.; Schmidt, S.M.; Swaffin-Smith, C.; Wilkinson, I. Patterns of Managerial Influence: Shotgun Managers, Tacticians, and Bystanders. Organ. Dyn. 1984, 12, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, L.K.; Andersen, P.A. Close Encounters: Communication in Relationships, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- INPI. Instituto Nacional de Propriedade Intelectual. 2021. Available online: http://www.inpi.gov.br/ (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Semprini, A. A Marca Pós-Moderna: Poder e Fragilidade da Marca na Sociedade Contemporânea; Estação das Letras e Cores: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, H. Marketing the City: The Role of Flagship Developments in Urban Regeneration; Taylor & Francis E-Library: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares, F. Gestão da Marca: Estratégia e Marca; E-Papers: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Iasbeck, L.C. A Arte dos Slogans: Técnicas de Construção das Frases de Efeito do Texto Publicitário; Annablume: São Paulo, Brazil, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, R. Branding: Uma nova filosofia de gestão. ESPM 2003, 10, 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, B.A.; Knapp, T.; Knapp, T.R. Dictionary of Nursing Theory and Research; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gbrich, C. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, L.; Dias, F.; Araújo, A.; Andrés Marques, I. A destination imagery processing model: Structural differences between dream and favourite destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.C. Narrative analysis: Exploring the whats and hows of personal stories. Qual. Res. Health Care 2015, 1, 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K.S. A Lógica da Pesquisa Científica, 2nd ed.; Cultrix: São Paulo, Brazil, 1975. [Google Scholar]

| Author | Concept | Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Val [25] | In systematic studies, intuitive and conceptual types and differences are often used to define categories that contrast with each other. | Typology |

| Raffestin [18]; Flores [19] | The boundaries of the territory are defined by power relations among social actors (Raffestin, 1993). Territory as a place for strategic connections (Flores, 2006). | Territory |

| Hall [26] | A connection between something and its meaning. Refers to a way of seeing the world, of expressing the vision of a group of people (social actors). | Territorial representation |

| Minayo [27] | The ways in which society’s reality can be expressed. | |

| Moscovici [28] | Classification system. | |

| Almeida [29] Almeida [2] | Cultural, economic, social, environmental, and political dimensions are part of development. | Types of developments |

| Castro [30] | Scales indicate different types of space coverage (country, region, state, city, street, etc.). It can also be a strategy of social actors in perceiving reality as a representation. | Geographic scale |

| Sabourin [31] | A social or economic agent is an individual or an institution that carries out an activity or maintains relationships within a given territory. | Socials actors |

| Kotler [32] | Corresponds to the geographical scale on which products are marketed. | Brand scope |

| Almeida [33] | Corresponds to a list of cities classified according to predetermined criteria (e.g., best cities to live or work, smart cities, sustainable cities, etc.). | Urban ranking |

| Pecquer [20] | Two territory formats: top-down and bottom-up. | Territorial process |

| Esteves [34] | A place’s inclination or tendency towards certain areas, such as social, cultural, political, economic, etc. | Vocation or function city |

| Sampaio [35] | Refers to the consumer group that is targeted in the sale of products. Target segments and target markets are also terms for this demographic group. | Brand audience |

| Ries and Trout[36] | Place where the brand is in the consumer’s mind. | Brand positioning |

| Kipnis et al. [37] Guerrero and Andersen [38] | Power as expressed in the relationship between people and social groups. | Power relations |

| INPI [39] | Brands can be visual, verbal, or mixed. | Brand type |

| Almeida [2] | The territorial brand is also discursive. | |

| Semprini [40] | Product brands can be viewed from an institutional (long-term) and promotional (short-term) perspective. | Perspective |

| Kotler et al. [4]; Smyth [41] | Based on the 4 Ps model (product, price, place, and promotion), marketing deals with companies, their products, and services. This includes product logistics, product management, tangible aspects, tactics, and quantitative measurement. | Product management aspect |

| Tavares [42] Keller [3] | Brand management is the strategic management of the product brand, considering product and brand as distinct elements. Management, relationships between brand and target-consumer audience, intangible aspects, strategy, and qualitative measurement are considered in this concept. | Brand management aspect |

| Aaker [14] | A logo is the graphic identification of the brand and not the brand itself. | Logo |

| Logo | Territorial Brand (60 Brands) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand | Slogan | Country | State | Region | City | Island | Route | Port | Generic Term | |

| Vale dos Vinhedos (Brazil) | Patrimônio Histórico e Cultural do Rio Grande do Sul | × | |||||||

| São Paulo (Brazil) | Viva tudo isso! | × | |||||||

| El Salvador | Great like our people | × | |||||||

| Colômbia | Colombia. Es pasión | × | |||||||

| Porto Maravilha (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) | Not found | × | |||||||

| Cais do Mauá (Porto Alegre, Brazil) | Cais Mauá de todos | × | |||||||

| Lisboa (Portugal) | Lado bonito dos negócios | × | |||||||

| Porto (Portugal) | Porto. Ponto. | × | |||||||

| Dubai | City where extraordinary things happen | × | |||||||

| Mônaco | Not found | × | |||||||

| Las Vegas | What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas | × | |||||||

| Caminho de Santiago | El camino francês | × | |||||||

| New York | I love NY | × | |||||||

| Fernando de Noronha (Brazil) | Not found | × | |||||||

| Peru | A country for everyone | × | |||||||

| Espanha | Tudo debaixo do sol | × | |||||||

| Portugal | Not found | × | |||||||

| Pelotas (Brazil) | Sou + Pel | × | |||||||

| Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) | Marca registrada do Brasil | × | |||||||

| Brazil | Sensacional | × | |||||||

| Amsterdan (Alemanha) | I am Amsterdan | × | |||||||

| Silicon Valley | Not found | × | |||||||

| Corede VRP (Brazil) | Not found | × | |||||||

| União Europeia | Not found | × | |||||||

| Mercosul | Not found | × | |||||||

| Porto Alegre (Brazil) | Multicultural | × | |||||||

| Vancouver (Canada) | Not found | × | |||||||

| Montreal (Canada) | Not found | × | |||||||

| Toronto (Canada) | Canada’s Downtown | × | |||||||

| Brasília (Brazil) | Not found | × | |||||||

| Austrália | Australia Unlimited | × | |||||||

| Cuba | Autêntica Cuba | × | |||||||

| Italy | It | × | |||||||

| Egipt | Where it all begins | × | |||||||

| Estados Unidos (EUA) | Discover the america and visit The USA | × | |||||||

| Bahamas | 700 islands. A milion stories | × | |||||||

| China | Like never before | × | |||||||

| Hong Kong | Asia’s world city | × | |||||||

| India | Inacredible India | × | |||||||

| Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil) | Um grande destino | × | |||||||

| Costa Rica | No Artificial Ingredients | × | |||||||

| Honduras | Somos para ti | × | |||||||

| México | Vive hoy, vive tuyo | × | |||||||

| Russia | O mundo inteiro na Rússia | × | |||||||

| New Zealand | 100% Pure | × | |||||||

| Japan | Japan. Endless. Discovery | × | |||||||

| Not found | Jerusalem | Not found | × | |||||||

| Not found | Terra Santa | Not found | × | |||||||

| Rio Grande do Norte, Brasil | Tudo começa aqui | × | |||||||

| Not found | Cape Town, South Africa | Mother City | × | |||||||

| Melbourne | Melbourne’s Diversity as a Sacred Concept | × | |||||||

| Praga, República Tcheca | Prague: emotions identity | × | |||||||

| Moldova | Discover the routes of life | × | |||||||

| Singapore | Your Singapore | × | |||||||

| Moscou | Wow Moscou | × | |||||||

| Canadá | Keep exploring | × | |||||||

| Genova | More than this | × | |||||||

| Bolívia | Corazón del Sur | × | |||||||

| Bulgária | A discovery to share | × | |||||||

| Eslovênia | Slovenijo? Utim (I feel Slovenia) | × | |||||||

| Smart city, strategic digital city, digital city, and others | × | |||||||||

| Territorial Brand Categories | Types of Territorial Brands | Analyze | Concept for Each Brand Category | Analyzed Brands |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Geographical | Indication of Origin (IP) and Denomination of Origin (DO) | Of the investigated brands, only Vale dos Vinhedos had a geographic certification. According to INPI (2021), only the brands that result from combining a culture’s know-how with the geographical conditions of that region are officially certified. However, not all territorial brands can obtain these certifications because they do not refer to a specific product but to a territorial reputation or another symbolic characteristic. | Geographical territorial brand: a brand that relies on the production of a specific product (cheese, wine, handicrafts, etc.) and is registered in its country of origin. | Vale dos Vinhedos (Brazil) |

| 2—Gender | Male, female, undefined, and friendly | Brand perceptions are influenced by the shape of the logo. According to Perez (2004), straight lines are associated with male brands, while sinuous shapes are associated with female brands. Territorial brands are also influential in shaping perceptions. In addittion to the right angles (male) and sinuous shapes (female), we see that these brands present a certain blurring of right or sinuous angles, and therefore we call them indefinite brands. There are also many brands with multiple colors, but this is not recommended for product brands due to the high cost of reproducing them in graphics. This type of brand is called friendly. | Gender territorial brand: When a brand’s logo has mostly right angles, it is considered masculine. If a logo has curved shapes, it is considered feminine. Logos that do not have a majority of right or sinuous angles are undefined gender brands. “Friendly” territorial brands use straight and sinuous angles, as well as multiple colors, in an attempt to encompass different cultural and territorial identities. | Male’: Lisbon, Monaco, Toronto, Camino de Santiago de Compostela. Female: Brazil, Egypt, Peru. Undefined: Cuba, Porto, Rio de Janeiro, European Union. Friendly: El Salvador, Colombia, São Paulo. |

| 3—Dimensional | Political, cultural, economic, social, environmental, religious and technological | Some brands highlighted their cultural dimensions. Not every brand displays its culture, however. Based on these findings, we posited that brands have multiple dimensions. | Dimensional territorial brand: Brands can be seen from several perspectives, some obvious and others hidden (consciously or unconsciously). Moreover, a brand can have more than one dimension, revealing the interests of actors in a given space. | Political: Brasilia. Cultural: Peru, Spain. Economic: Mercosur, European Union. Environmental: Fernando de Noronha. Religious: Holy Land, Jerusalem. Technological: Silicon Valley. Social: Cais do Mauá (Brazil). |

| 4—Multiple scales | Local, regional, state, national, international | Upon analyzing the brands, we found that they had different scales. However, there were local brands on an international scale, as is the case of São Paulo in Brazil and Porto in Portugal. This means that some territorial brands exist at multiple scales. | Territorial brand by scale: In the production of a territory, social actors have interests that are represented. A territorial brand by scale may be local when its power relations are directed at a smaller scale, as in a city or neighborhood, or it may be national when directed at a larger scale, such as a country; or it may exceed a scale, as in the case of a territorial brand at international level. The use of one or more scales reveals the scope of the relationships among social actors as they produce and use the territory. | Local: Porto Maravilha (RJ, Brazil). Regional: Pelotas (Brazil). State: Rio Grande do Sul. National: Brasilia. International: São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil); Monaco, Dubai, Jerusalem |

| 5—Functional or vocational | Port, entrepreneurial, multicultural, technological, tourist, religious, urban revitalization | In some brands, the focus was on the functions (vocation) of the city, such as the port (Porto, Portugal; Porto Maravilha, Brazil) or business incubator (Lisbon, Portugal). | Vocational or functional territorial brand: Providing a role for a territory justifies the actions of social actors, hiding or making less apparent the actions of other groups of social actors. Producing symbolic debates about production and territory ownership is a way of generating conflict. | Port: Porto (Portugal) and Porto Maravilha (Brazil). Entrepreneurial: Lisbon (Portugal) Multicultural: Porto Alegre (Brazil). Technological: Silicon Valley. Tourist: Spain. Religious: The Way of Saint James of Compostela, Jerusalem, Holy Land. Urban revitalization: Business improvement districts (e.g., Times Square, NY) |

| 6—Generic or commodities | Smart city, strategic digital city, sustainable city, compact city (and other terms) | Some of the researched brands emphasize generic terms, such as smart city, making a territory known by this nomenclature. | Generic territorial brand or commodity: In this case, the territory (city) should be viewed from generic perspectives, such as smart or sustainable. Cities using it are those that have not yet established their territorial identity, which makes it more practical to adopt a commodity territorial brand rather than to assume a position that will cause a symbolic conflict between different social actors. This category includes current imaginaries, including technological imaginaries, which are based on desirable and achievable futures. | Smart city: Toronto (Canada) Sustainable city: Fernando de Noronha (Brazil). (and other terms) |

| 7—In crisis | Age (re-branding) or territorial/cultural identity | Some brands frequently change their logos due to their “age” (time on the market) or a dispute over territorial/cultural identity. Such brands are considered to be in crisis. | Territorial brand in crisis: Those that have not established an institutional brand, using brands that have little temporality (in their logo or in relation to their identity) | Egypt, Florianópolis (Brazil) |

| 8—Personified | Indecisive/insecure, temporary/ephemeral/shifting, innovative, changing, secure/constant/resilient, fluid/modern, emotional, mysterious, rebellious, articulate, exotic, luxurious | Product brands commonly use a personification strategy to become closer to consumers, and we perceive that this strategy is also used in territorial brands. Some are more unpredictable, constantly changing their brand design; others are more secure, retaining the same brand since the first version; the temporary ones are those marked by social actors that, in practice, are unaware of the concept of territorial brand and its management (place branding). The mysterious brands use exotic aspects and myths of their culture. Territorial luxury brands are divided into triple-A, double-A, and just A (similar to product brands), referring to the luxury exhibited somehow in the territory. | Personified territorial brand: The brand that displays a human characteristic, such as insecure, secure, innovative, mutant, mysterious, and so on. | Safe territorial brands: Spain and Portugal. Temporary territorial brand: Porto Alegre (Brazil). Exotic territorial brand: India. Luxury territorial brands: Dubai and Monaco. Mutant territorial brand: Melbourne |

| 9—Identity | Established or under construction | As in the case of Porto Alegre (Brazil), brands were used as a strategy to establish a new identity for the territory. There are territorial brands that can be identified based on their identity. | Territorial brand by identity: A territorial brand is a place where social actors compete for the appropriation of the territory’s identity. Brands compete for hegemonic identity while at the same time maintaining it. In this scenario, more than one brand can be mentioned simultaneously, as well as the cultural and political issues of the territory. | Under construction: Porto Alegre (Brazil). Established: Portugal. |

| 10—Reputation | (n types of stereotypes and reputations) | Based on the analysis of the brands, we found instances of stereotypes spreading due to the reputation of their territories. | Territorial brand by reputation: These are brands that create reputations, positive or negative, for the territories, justifying the dynamics in force in the territory. | Las Vegas (drug city). Holy Land (land blessed by God). Brazil (country of football). |

| 11—Territorial representation | Material/immaterial | The logos of some brands exalt material aspects of their territories, such as beaches, statues, urban furniture, etc. Still, some brands used, in their logos, symbols of materialism (symbolic), such as culture. | Territorial brand by representation: When using symbolic aspects, brands can represent territories both materially and immaterially. Generally, it is more common for territorial brands to use immaterial representations recurrently associated with tourism. In their use of landscape fragments, they refer to the material representation of the territory. | Fernando de Noronha (Brazil) Brasília e São Paulo (Brazil). Porto (Portugal) Australia, El Salvador, Peru, Montreal, Dubai The Way of Saint James of Compostela, New York. |

| 12—Development | Urban, territorial, regional, economic, cultural, social, environmental, and technological | Analyzing the brands, we found that there are different types of development in each of them. | Territorial brand by development: A territorial brand typically uses more than one development type. In the production, use, and appropriation of the territory, this choice varies depending on the interests of social actors. | All brands analyzed |

| 13—Situation | Organic, planned, occasional, and out of necessity | The formation of some brands occurs without prior planning; others are planned; some are born out of an event that occurs in the market; others are born out of a need. Organic territorial brands develop from reputations and stereotypes. When the brand is planned, a persuasive structure is created that supports and legitimizes the discourse of a given group of actors. An occasional territorial brand uses a specific circumstance to link itself to a particular area. In a time of crisis, be it dimensional or scalar, the territorial brand serves as a strategy for social actors to emerge from it. | Territorial brand by situation: Territorial brands result from social actors taking advantage of certain circumstances to create them. Brands are not designed in advance; rather, they are created in response to a given situation. | The organic type was present in all brands. Planned territorial brand: Dubai, Lisbon, Peru. Occasional territorial brand: Porto Alegre and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil). Territorial brand out of necessity: Spain. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almeida, G.G.F.d.; Cardoso, L. Discussions between Place Branding and Territorial Brand in Regional Development—A Classification Model Proposal for a Territorial Brand. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116669

Almeida GGFd, Cardoso L. Discussions between Place Branding and Territorial Brand in Regional Development—A Classification Model Proposal for a Territorial Brand. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116669

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmeida, Giovana Goretti Feijó de, and Lucília Cardoso. 2022. "Discussions between Place Branding and Territorial Brand in Regional Development—A Classification Model Proposal for a Territorial Brand" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116669

APA StyleAlmeida, G. G. F. d., & Cardoso, L. (2022). Discussions between Place Branding and Territorial Brand in Regional Development—A Classification Model Proposal for a Territorial Brand. Sustainability, 14(11), 6669. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116669