Indigenous Knowledge on the Uses and Morphological Variation among Strychnos spinosa Lam. at Oyemeni Area, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

Ethnobotanical Survey

2.3. Data Analysis

- FC: the number of participants per age group

- N: the number of participants per gender.

3. Results

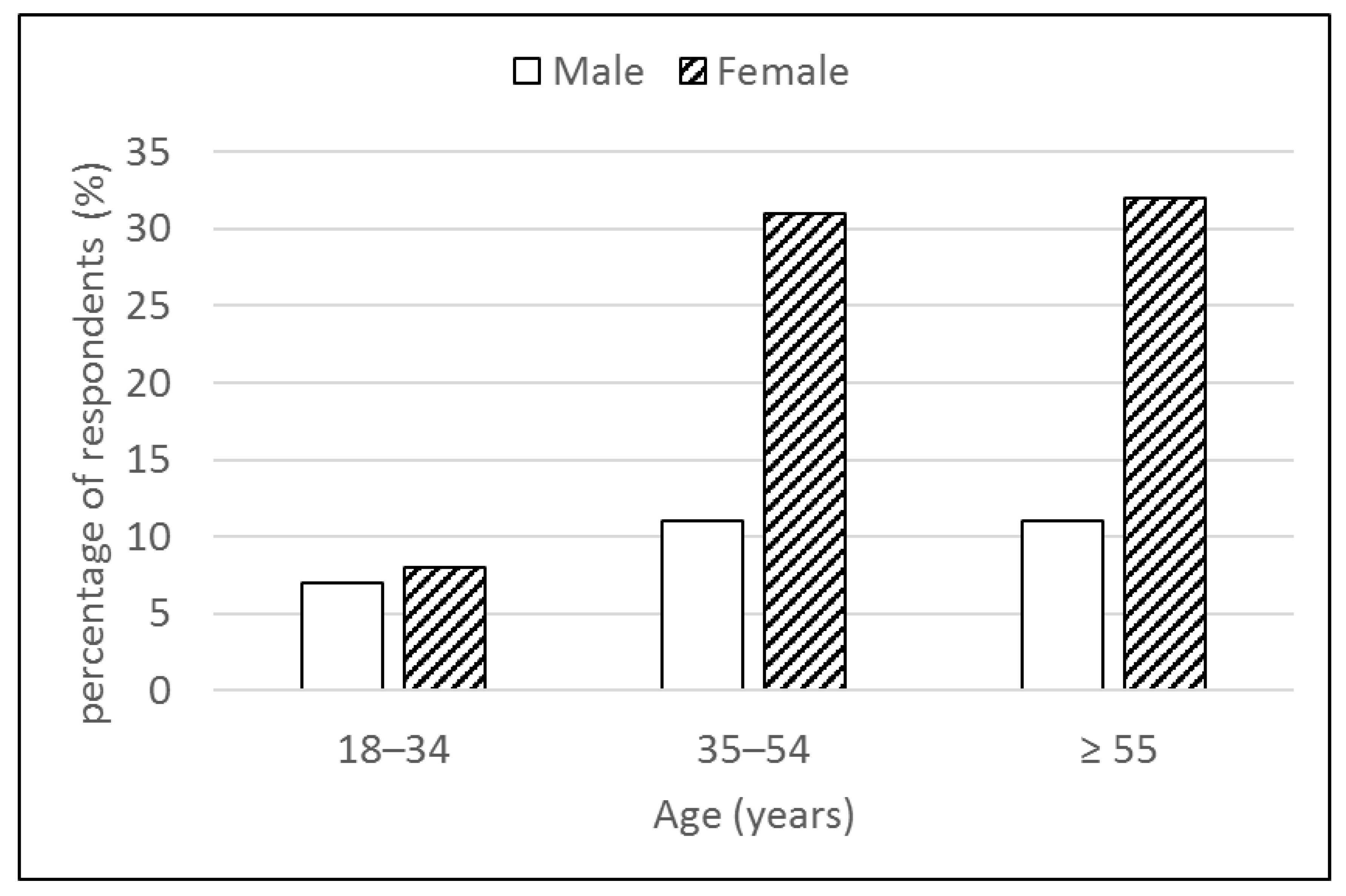

3.1. Socio-Demographic Information

3.2. The Significance of the isiZulu Name “umHlala” in the Context of Strychnos spinosa

3.3. Uses of Strychnos spinosa

- (a)

- Fermented maize meal (umBhantshi)

- (b)

- Fruit

- (c)

- Juice

- (d)

- Alcohol

- (e)

- Fermented porridge (amaHewu)

- (f)

- Homestead protection

- (g)

- Snakebite

- (h)

- Firewood

- (i)

- Food allergy

- (j)

- Increasing livestock

- (k)

- Stomachache

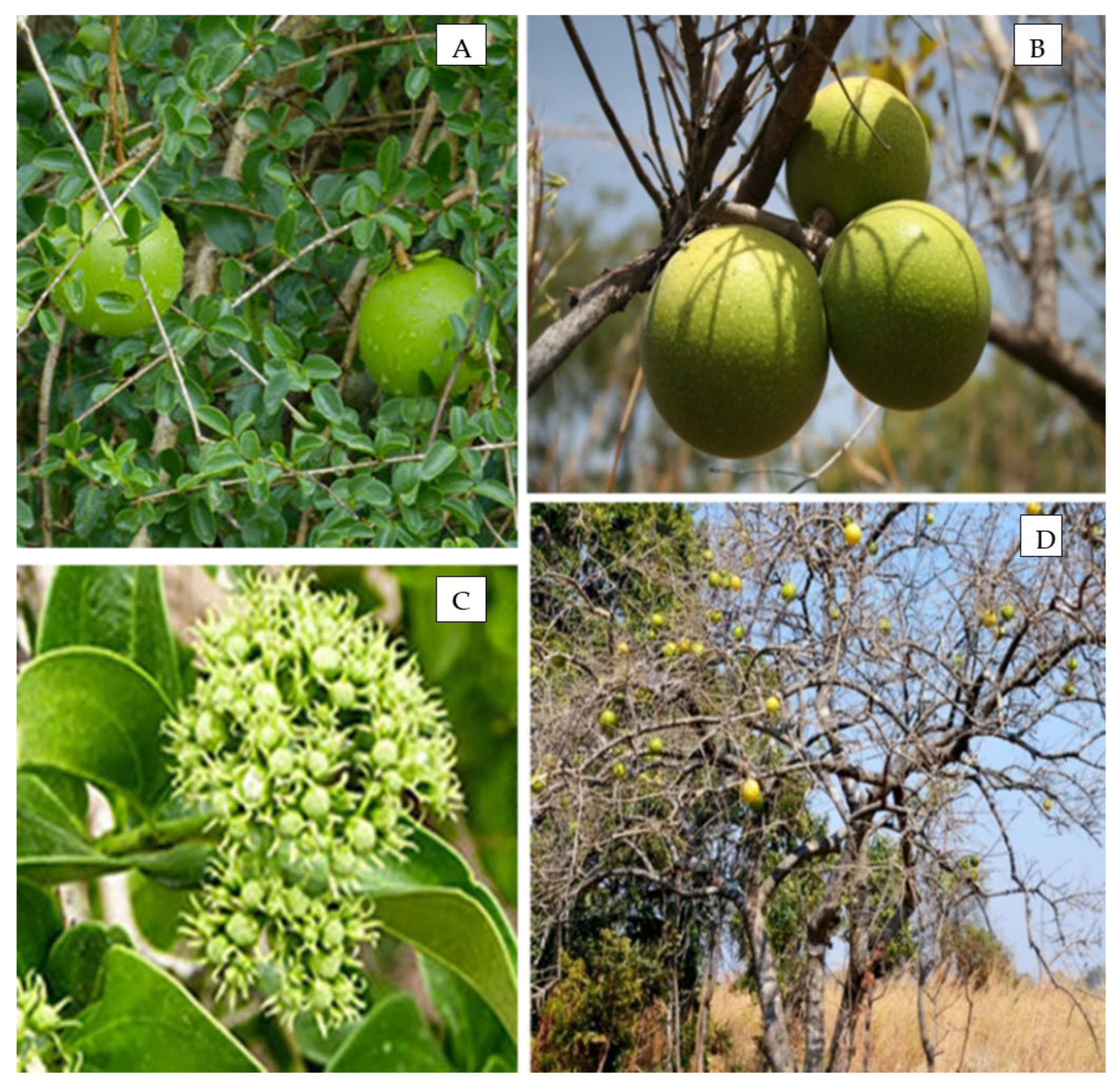

3.4. Morphological and Organoleptic Variation of Strychnos spinosa

3.4.1. Leaf Traits

- (a)

- Leaf colour

- (b)

- Leaf shape

3.4.2. Fruit Traits

- (a)

- Rind colour

- (b)

- Size

- (c)

- Rind texture

- (d)

- Fruit pulp colour

- (e)

- Fruit pulp texture

- (f)

- Fruit taste

4. Discussion

4.1. Socio-Demographic Information

4.2. The Significance of the isiZulu Name “umHlala” in the Context of Strychnos spinosa

4.3. Indigenous Uses of Strychnos spinosa

4.4. Strychnos Spinosa Fermented Food and Drinks

- (a)

- Fermented maize meal (umBhantshi)

- (b)

- Fermented porridge (amaHewu)

- (c)

- Alcohol

4.5. Fresh Fruit

4.6. Juice

4.7. Jam

4.8. Homestead Protection and Livestock Increase

4.9. Snakebite

4.10. Firewood

4.11. Food Allergy and Stomachache

4.12. Morphological Variation of Strychnos spinosa

- (a)

- Leaf traits

- (b)

- Fruit traits

4.13. Organoleptic Variation of Strychnos spinosa

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Avakoudjo, H.G.G.; Achille, H.; Rodrigue, I.; Mamidou, W.K.; Achille, E.A. Local knowledge, uses and factors determining the use of Strychnos spinosa organs in Benin (West Africa). Econ. Bot. 2019, 74, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankoana, S. Indigenous plant foods of Dikgale community in South Africa. J. Ethn. Foods 2021, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, B.; Gruber, F.; Finkeldey, R.; Gailing, O. Linking indigenous knowledge, plant morphology and molecular differentiation: The case of ironwood (Eusideroxylon zwageri Teijsm. et Binn.). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2016, 63, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansiime, M.K.; Ochieng, J.; Kessy, R.; Karanja, D.; Romney, D.; Afari-Sefa, V. Changing knowledge and perceptions of African indigenous vegetables: The role of community-based nutritional outreach. Dev. Pract. 2018, 28, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Omotayo, A.O.; Aremu, A.O. Evaluation of factors influencing the inclusion of indigenous plants for food security among rural households in the North-West Province of South Africa. Sustainability 2021, 12, 9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R. Wild edible plants: A change for future diet and health. Plants 2022, 11, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, L.; Pillay, K.; Siwela, M.; Modi, A.; Mabhaudhi, T. Food and nutrition insecurity in selected rural communities of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa-Linking human nutrition and agriculture. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masekoameng, M.R.; Molotja, M.C. The role of indigenous knowledge systems for rural households’ food security in Sekhukhune district, Limpopo Province, South Africa. J. Consum. Sci. 2019, 4, 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mwamba, C.K. Monkey Orange: Strychnos cocculoides; Crops for the Future: Cambridge, UK, 2006; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Ngadze, R.T. Value Addition of Southern African Monkey Orange (Strychnos spp.): Composition, Utilization and Quality; Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karambiri, M.; Elias, M.; Vinceti, B.; Grosse, A. Exploring local knowledge and preference for shea (Vitellaria paradoxa) ethnovarieties in Southwest Burkina Faso through a gender and ethnic lens. For. Trees Livelihoods 2017, 26, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leakey, R.B.R.; Tientcheu Avana, M.-L.; Awazi, N.P.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Hendre, P.S.; Degrande, A.; Hlahla, S.; Manda, L. The future of food: Domestication and commercialization of indigenous food crops in Africa over the third decade (2012–2021). Sustainability 2022, 14, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, N.N.; Morstert, T.H.C.; Dzikiti, S.; Ntuli, N.R. Prioritization of indigenous fruit tree species with domestication and commercialization potential in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2020, 67, 1567–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saka, J.D.K.; Msonthi, J.D. Nutritional value of edible fruits indigenous wild tree in Malawi. For. Ecol. Manag. 1994, 64, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madzimure, J.; Nyahangare, E.T.; Hamudikuwanda, H.; Hove, T.; Belmain, S.R.; Stevenson, P.C.; Mvumi, B.M. Efficacy of Strychnos spinosa (Lam.) and Solanum incanum L. aqueous fruit extracts against cattle ticks. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2013, 45, 1341–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittikpina, N.K.; Atapama, W.; Hoekou, Y.; Diop, Y.M.; Batawila, K.; Akapagana, K. Strychnos spinosa L.: Comprehensive review on its medicinal and nutritional uses. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 17, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashile, S.P.; Tshisikwane, M.P.; Masevhe, N.A. Indigenous fruit plants of the Mapulana of Enhlanzeni district in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magwede, K.; van Wyk, B.E.; van Wyk, A.E. An inventory of Vhavenda useful plants. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 122, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfukwa, T.M.; Chikwamba, O.C.; Katiyatiya, C.L.F.; Fawole, O.A.; Manley, M.; Mapiye, C.J. Southern African indigenous fruits and their byproducts: Prospects as food antioxidants. Funct. Foods 2020, 75, 104220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shai, K.N.; Ncama, K.; Ndhlovu, P.T.; Struwig, M.; Aremu, A.O. An exploratory study on the diverse uses and benefits of locally-sourced fruit species in three villages of Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Foods 2020, 9, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadima, L.J. User Attitudes to Conservation and Management Options for the Ongoye Forest Reserve, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa; University of KwaZulu-Natal: Durban, South Africa, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, S.C.; Lawes, M.J. Edge effects at an induced forest-grassland boundary: Forest birds in the Ongoye Forest Reserve, KwaZulu-Natal. S. Afr. J. Zool. 1997, 32, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongoye Forest Reserve: Birdlife Zululand. 2015. Available online: http:www.birdlifezululand.co.za/birdingsites/southernzululand/mtunzini/ongoyeforest (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Akweni, A.L.; Sibanda, S.; Zharare, G.E.; Zimudzi, C. Fruit-based allometry of Strychnos madagascariensis and S. spinosa (Loganiaceae) in the savannah woodlands of the Umhlabuyalingana Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Trees For. People 2020, 2, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, A.I.; Adebayo, S.A.; Mohammed, A.; Magaji, R.A.; Ayo, J.O.; Suleman, M.M.; Saleh, M.I.A.; Sadan, Y.; Eloff, J.N. In-vitro lipoxygenase inhibitory activity and total flavonoid of Strychnos spinosa leaf extracts and fractions. Niger. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 13, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Asuzu, C.U.; Nwosu, M.O. Comparative study of the leaf morphology and anatomy of selected Strychnos species: Strychnos spinosa Lam., Strychnos Innocua Del., and Strychnos usambarensis Gilg found in three ecological zones in Nigeria. Int. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2019, 19, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu, C.; Ndinda, C. Female Household Headship and Poverty in South Africa: An Employment-Based Analysis. 2018. Available online: https://www.econrsa.org/system/files/publications/working_papers/working_paper_761.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Ngadze, R.T.; Verkerk, R.; Nyanga, L.K.; Fogliano, V.; Linnemann, A.R. Improvement of traditional processing of local monkey orange (Strychnos spp.) fruits to enhance nutrition security in Zimbabwe. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wayland, C.; Walker, L.S. Length of residence, age and patterns of medicinal plant knowledge and use among women in the urban Amazon. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2014, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaoue, O.E.; Coe, M.A.; Bond, M.; Hart, G.; Seyler, B.C.; McMillen, H. Theories and major hypotheses in ethnobotany. Econ. Bot. 2017, 71, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Andel, T.R.; van’t Klooster, E.A.; Quiroz Villarreal, D.K.; Towns, A.M.; Ruysschaert, S.; van den Berg, M. Local plant names reveal that enslaved Africans recognized substantial parts of the New World flora. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mace, G.M. The role of taxonomy in species conservation. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khasbagan, S. Indigenous knowledge for plant sciences diversity: A case study of wild plants’ folk names used by the Mongolians in Ejina desert area, Inner Mongolia, P.R. China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al Azharia, J. How plant names reveal folk botanical classification, trade, traditional uses and routes of dissemination (II), in Asian studies. Int. J. Asian Stud. 2006, 7, 77–128. [Google Scholar]

- De Siqueira, J.I.A.; Vieira, I.R.; Chaves, E.M.F.; Sanabria-Diago, O.L.; Lemos, J.R. Biocultural behavior and traditional practices on the use of species of Euphorbiaceae in rural home gardens of the Semiarid Region of Piauí State NE, Brazil. Caldasia 2020, 42, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Albuquerque, U.P. Re-examining hypotheses concerning the use and knowledge of medicinal plants: A study in the Caatinga vegetation of NE Brazil. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alencar, N.L.; Araújo, T.A.; Amorim, E.L.C.; Albuquerque, U.P. The inclusion and selection of medicinal plants in traditional pharmacopoeias—Evidence in support of the diversification hypothesis. Econ. Bot. 2010, 64, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rayne, K.K.; Adebo, O.A.; Ngobese, N.Z. Nutritional and physicochemical characterization of Strychnos madagascariensis Pior. (Black monkey orange) seeds as a potential food source. Foods 2020, 9, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanza, N.; Musakwa, W. Revitalizing indigenous ways of maintain food security in a changing climate: Review of the evidence base from Africa. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2022, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar]

- Ngadze, R.T.; Linnemann, A.R.; Nyanga, L.K.; Fogliano, V.; Verkerk, R. Local processing and nutritional composition of indigenous fruits: The case of monkey orange (Strychnos spp.) from Southern Africa. Food Rev. Int. 2017, 33, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekpa, O.; Palacios-Rojas, N.; Kruseman, G.; Fogliano, V.; Linnemann, A.R. Sub-Saharan African maize-based foods processing practices, challenges and opportunities. Food Rev. Int. 2019, 35, 609–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Masarirambi, M.T.; Mhazo, N.; Dlamini, A.M.; Mutukumira, A.N. Common indigenous fermented foods and beverages produced in Swaziland: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 46, 505–508. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, M.R.; Anandharaj, M.; Ray, R.C.; Rani, R.P. Fermented fruits and vegetables of Asia: A potential source of probiotics. A potential source of probiotics. Biotechnol. Res. Int. 2014, 10, 250424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhata, S.G.; Ayua, E.; Kamau, E.H.; Shingiro, J.B. Fermentation and germination improve nutritional value of cereals and legumes through activation of endogenous enzymes. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 2446–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akinnifesi, F.K.; Kwesiga, F.; Mhango, J.; Chilanga, T.; Mkonda, A.; Kadu, C.A.C.; Kadzere, I.; Mithofer, D.; Saka, J.D.K.; Sileshi, G.; et al. Towards the development of miombo fruit trees as commercial tree crops in southern Africa. For. Trees Livelihoods 2006, 16, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; de Brito, E.S.; de Oliveira Silva, E. Maboque/Monkey Orange-Strychnos Spinose; Fruits, E., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejene, T.; Agamy, M.S.; Agúndez, D.; Muartín-Pinto, P. Ethnobotanical survey of wild edible fruit tree species in lowland areas of Ethiopia. Forests 2020, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prins, H.; Maghembe, J.A. Germination studies on seed of fruit trees indigenous to Malawi. For. Ecol. Manag. 1994, 64, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaba, F.; Chirwa, P.; Prozesky, H. The contribution of indigenous fruit trees in sustaining rural livelihoods and conservation of natural resources. J Hortic For. 2009, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Aremu, A.O.; Moyo, M. Health benefits and biological activities of spiny monkey orange (Strychnos spinosa: An African indigenous fruit tree). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 283, 114704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Hu, G.; Ranjitkar, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. Implications of ritual practices and ritual plants uses on nature conservation: A case study among the Naxi in Yunnan Province, Southwest China. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bvenura, C.; Sivakumar, D. The role of wild fruits and vegetables in delivering a balanced and healthy diet. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankoana, S. Sustainable use and management of indigenous plant resources: A case of Mantheding community in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Sustainability 2016, 8, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Isa, A.I.; Dzoyem, J.P.; Adebayo, S.A.; Suleiman, M.M.; Eloff, J.N. Nitric oxide inhibitory activity of Strychnos spinosa (Loganiaceae) leaf extracts and fractions and fractions. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 13, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, D.J.; Faiz, M.A.; Abela-Ridder, B.; Ainsworth, S.; Bulfone, T.C.; Nickerson, A.D.; Habib, A.G.; Junghanss, T.; Fan, H.W.; Turner, M.; et al. Strategy for a globally coordinated response to a priority neglected tropical disease: Snakebite envenoming. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gómez-Betancur, I.; Gogineni, V.; Salazar-Ospina, A.; León, F. Perspective on the therapeutics of anti-snake venom. Molecules 2019, 24, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Félix-Silva, J.; Silva-Junior, A.A.; Zucolotto, S.M.; Fernandes-Pedrosa, M.F. Medicinal plants for the treatment of local tissue damage induced by snake venoms: An overview from traditional use to pharmacological evidence. Evid. Based Complement Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahru, T.; Asfaw, Z.; Demissew, S. Indigenous knowledge of fuel wood (charcoal and/or firewood) plant species used by the local people in and around the semi-arid Awash National Park, Ethiopia. J. Ecol. Nat. 2012, 4, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Gu, J.Q.; Li, L.S.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, H.T.; Wang, Y.; Chang, C.; Sun, J.L. The association between intestinal bacteria and allergic diseases-cause or consequence? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratap, K.; Taki, A.C.; Johnson, E.B.; Lopata, A.L.; Kamath, S.D. Comprehensive review on natural bioactive compounds and probioactive compounds and probiotics as potential therapeutics in food allergy treatment. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndarubu, T.A.; Rahinat, G.; Majiyebo, A.J.; Julius, I.N.; Moshood, A.O.; Damola, A.S.; Eustace, B.B. Strychnos spinosa as a potential anti-oxidants and anti-microbial natural product. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 2, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Kang, L.; Zhao, J.; Qi, N.; Li, R.; Wen, Z.; Kassout, J.; Peng, C.; Lin, G.; Zheng, H. Quantifying leaf trait covariations and their relationships with plant adaptation strategies along an aridity gradient. Biology 2021, 10, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Prentice, I.C.; Wright, I.J.; Evans, B.J.; Togashi, H.F.; Caddy-Retalic, S.; Mclnerney, F.A.; Sparrow, B.; Leitch, E.; Lowe, A.J. Components of leaf trait variation along environmental gradients. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, J.S.; Corney, D.; Clark, J.Y.; Remagnino, P.; Wilkin, P. Plant species identification using digital morphometrics: A review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 7562–7573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldechen, J.; Rzanny, M.; Seeland, M.; Mader, P. Automated plant species identification—Trends and future directions. PLoS Comput. Biol 2018, 14, e1005993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ren, J.; Ji, X.; Wang, C.; Hu, J.; Nervo, G.; Li, J. Variation and genetic parameters of leaf morphological traits of eight families from Populus simonii x P. nigra. Forests 2020, 11, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngemakwe, P.H.N.; Remize, F.; Thaoge, M.L.; Sivakumar, D. Phytochemical and nutritional properties of underutilised fruits in the southern African region. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 113, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitrit, Y.; Loison, S.; Ninio, R.; Dishon, E.; Bar, E.; Lewinsohn, E.; Mizrahi, Y. Characterisation of monkey orange (Strychnos spinosa Lam.), a potential new crop for arid regions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6256–6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, C.; Levitan, C.A. Explaining crossmodal correspondence between colours and taste. i-Perception 2021, 12, 20416695211018223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Use | Respondents | Gender | Age (Years) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F [N (%)] | 18–34 N(TFI; SFI) | 35–54 N(TFI; SFI) | ≥55 N(TFI; SFI) | |||

| Food | Fermented maize meal (umBhantshi) | 97 | F [66 (68)] | 13 (13; 20) | 26 (27; 39) | 27 (28; 41) |

| M [31 (32)] | 12 (13; 39) | 9 (9; 29) | 10 (10; 32) | |||

| Fruit | 85 | F [61 (72)] | 26 (31; 43) | 5 (6; 8) | 30 (35; 49) | |

| M [24 (28)] | 10 (12; 42) | 6 (7; 25) | 8 (9; 33) | |||

| Juice | 23 | F [17 (74)] | 7 (30; 41) | 4 (17; 24) | 6 (26; 35) | |

| M [6 (26)] | 2 (9; 33) | 1 (4; 17) | 3 (13; 50) | |||

| Jam | 16 | F [4 (25)] | 4 (25; 100) | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | |

| M [12 (75)] | 6 (38; 50) | 2 (13; 17) | 4 (25; 33) | |||

| Alcohol | 7 | F [5 (71)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 5 (71; 100) | |

| M [2 (29)] | 0 (0; 0) | 2 (29; 100) | 0 (0; 0) | |||

| Fermented porridge (amaHewu) | 6 | F [5 (83)] | 1 (17; 20) | 2 (33; 40) | 2 (33; 40) | |

| M [1 (17)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 1 (17; 100) | |||

| Other | Homestead protection | 41 | F [29 (71)] | 3 (7; 10) | 7 (17; 24) | 19 (46; 66) |

| M [ 12 (29)] | 0 (0; 0) | 7 (17; 58) | 5 (12; 42) | |||

| Snakebite | 24 | F [15 (63)] | 3 (13; 20) | 4 (17; 27) | 8 (3; 53) | |

| M [ 9 (38)] | 0 (0; 0) | 5 (21; 56) | 4 (17; 44) | |||

| Fire | 10 | F [9 (90)] | 4 (40; 44) | 1 (10; 11) | 4 (40; 44) | |

| M [1 (10)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 1 (10; 100) | |||

| Food allergy | 10 | F [ 9 (90)] | 3 (30; 33) | 3 (30; 33) | 3 (30; 33) | |

| M [1 (10)] | 0 (0; 0) | 1 (10; 100) | 0 (0; 0) | |||

| Increasing livestock | 7 | F [7 (100)] | 0 (0; 0) | 5 (71; 71) | 2 (29; 29) | |

| M [0 (0)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | |||

| Stomachache | 7 | F [5 (71)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 5 (71; 100) | |

| M [2 (29)] | 0 (0; 0) | 2 (29; 100) | 0 (0; 0) |

| Leaf Trait | Total Mention per Category | Gender | Age (Years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FI | F [N (%)] | 18–34 N (TFI; SFI) | 35–54 N (TFI; SFI) | ≥55 N (TFI; SFI) | ||

| Colour | Green | 78 | F [68 (70)] | 7 (7; 10) | 30 (31; 44) | 31 (32; 46) |

| M [29 (30)] | 7 (7; 24) | 11 (11; 38) | 11 (11; 38) | |||

| Dark green | 22 | F [20 (74)] | 4 (15; 20) | 10 (37; 50) | 6 (22; 30) | |

| M [7 (26)] | 3 (11; 43) | 2 (7; 29) | 2 (7; 29) | |||

| Shape | Rounded | 74 | F [62 (74)] | 5 (6; 8) | 26 (31; 42) | 31 (37; 50) |

| M [22 (26)] | 4 (5; 18) | 8 (10; 36) | 10 (12; 45) | |||

| Elongated | 26 | F [18 (62)] | 3 (10; 17) | 7 (24; 39) | 8 (28; 44) | |

| M [11 (38)] | 4 (14; 36) | 3 (10; 27) | 4 (14; 36) | |||

| Fruit trait | ||||||

| Rind colour | Light green | 13 | F [19 (76)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 19 (76; 100) |

| M [6 (24)] | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 6 (24; 100) | |||

| Green | 39 | F [57 (78)] | 22 (30; 39) | 22 (30; 39) | 13 (18; 23) | |

| M [16 (22)] | 5 (7; 31) | 5 (7; 31) | 6 (8; 38) | |||

| Light yellow | 21 | F [30 (77)] | 10 (26; 33) | 10 (26; 33) | 10 (26; 33) | |

| M [9 (23)] | 2 (5; 22) | 2 (5; 22) | 5 (13; 56) | |||

| Yellow | 24 | F [31 (67)] | 14 (30; 45) | 15 (33; 48) | 2 (4; 6) | |

| M [15 (33)] | 8 (17; 53) | 7 (15; 47) | 0 (0; 0) | |||

| Intense yellow | 3 | F [2 (33)] | 1 (17; 50) | 1 (17; 50) | 0 (0; 0) | |

| M [4 (67)] | 2 (33; 50) | 2 (33; 50) | 0 (0; 0) | |||

| Size | Small | 31 | F [48 (77)] | 0 (0; 0) | 22 (35; 46) | 26 (42; 54) |

| M [14 (23)] | 1 (2; 7) | 7 (11; 50) | 6 (10; 43) | |||

| Medium | 22 | F [28 (64)] | 2 (5; 7) | 15 (34; 54) | 11 (25; 39) | |

| M [16 (36)] | 2 (5; 13) | 6 (14; 38) | 8 (18; 50) | |||

| Large | 46 | F [64 (70)] | 8 (9; 13) | 28 (31; 44) | 28 (31; 44) | |

| M [27 (30)] | 5 (5; 19) | 11 (12; 41) | 11 (12; 41) | |||

| Rind texture | Smooth | 73 | F [70 (80)] | 8 (10; 11) | 31 (40; 44) | 31 (40; 44) |

| M [28 (20)] | 7 (9; 25) | 11 (14; 39) | 10 (13; 36) | |||

| Rough | 30 | F [24 (65)] | 2 (5; 8) | 11 (30; 46) | 11 (30; 46) | |

| M [13 (35)] | 3 (8; 23) | 4 (11; 31) | 6 (16; 46) | |||

| Pulp colour | White | 8 | F [7 (70)] | 1 (10; 14) | 5 (50; 71) | 1 (10; 14) |

| M [3 (30)] | 1 (10; 33) | 2 (20; 67) | 0 (0; 0) | |||

| Yellow | 14 | F [10 (59)] | 3 (18; 30) | 3 (18; 30) | 4 (24; 40) | |

| M [7 (41)] | 3 (18; 43) | 2 (12; 29) | 2 (12; 29) | |||

| Light brown | 24 | F [24 (80)] | 6 (20; 25) | 8 (27; 33) | 10 (33; 42) | |

| M [6 (20)] | 2 (10; 33) | 1 (3; 17) | 3 (10; 50) | |||

| Brown | 54 | F [46 (69)] | 1 (1; 2) | 24 (36; 52) | 21 (31; 46) | |

| M [21 (31)] | 4 (6; 19) | 9 (13; 43) | 8 (12; 38) | |||

| Organoleptic Trait | ||||||

| Pulp texture | Watery | 33 | F [30 (70)] | 5 (15; 17) | 9 (27; 30) | 16 (48; 53) |

| M [13 (30)] | 3 (9; 23) | 6 (18; 46) | 4 (12; 31) | |||

| Thick | 67 | F [63 (72)] | 6 (7; 10) | 30 (34; 48) | 27 (31; 43) | |

| M [24 (28)] | 6 (7; 25) | 8 (9; 33) | 10 (11; 42) | |||

| Taste | Very sweet | 10 | F [11 (65)] | 1 (6; 9) | 4 (24; 36) | 6 (35; 55) |

| M [6 (35)] | 1 (6; 17) | 3 (2; 50) | 2 (12; 33) | |||

| Sweet | 58 | F [67 (69)] | 7 (7; 10) | 29 (30; 43) | 31 (32; 46) | |

| M [30 (31)] | 8 (8; 27) | 11 (11; 37) | 11 (11; 37) | |||

| Sour | 31 | F [36 (69)] | 2 (4; 6) | 17 (33; 47) | 17 (33; 47) | |

| M [16 (31)] | 6 (12; 38) | 5 (10; 31) | 5 (10; 31) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mbhele, Z.; Zharare, G.E.; Zimudzi, C.; Ntuli, N.R. Indigenous Knowledge on the Uses and Morphological Variation among Strychnos spinosa Lam. at Oyemeni Area, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116623

Mbhele Z, Zharare GE, Zimudzi C, Ntuli NR. Indigenous Knowledge on the Uses and Morphological Variation among Strychnos spinosa Lam. at Oyemeni Area, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116623

Chicago/Turabian StyleMbhele, Zoliswa, Godfrey Elijah Zharare, Clement Zimudzi, and Nontuthuko Rosemary Ntuli. 2022. "Indigenous Knowledge on the Uses and Morphological Variation among Strychnos spinosa Lam. at Oyemeni Area, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116623

APA StyleMbhele, Z., Zharare, G. E., Zimudzi, C., & Ntuli, N. R. (2022). Indigenous Knowledge on the Uses and Morphological Variation among Strychnos spinosa Lam. at Oyemeni Area, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sustainability, 14(11), 6623. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116623