Research on Traffic Design of Urban Vital Streets

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Design Methods

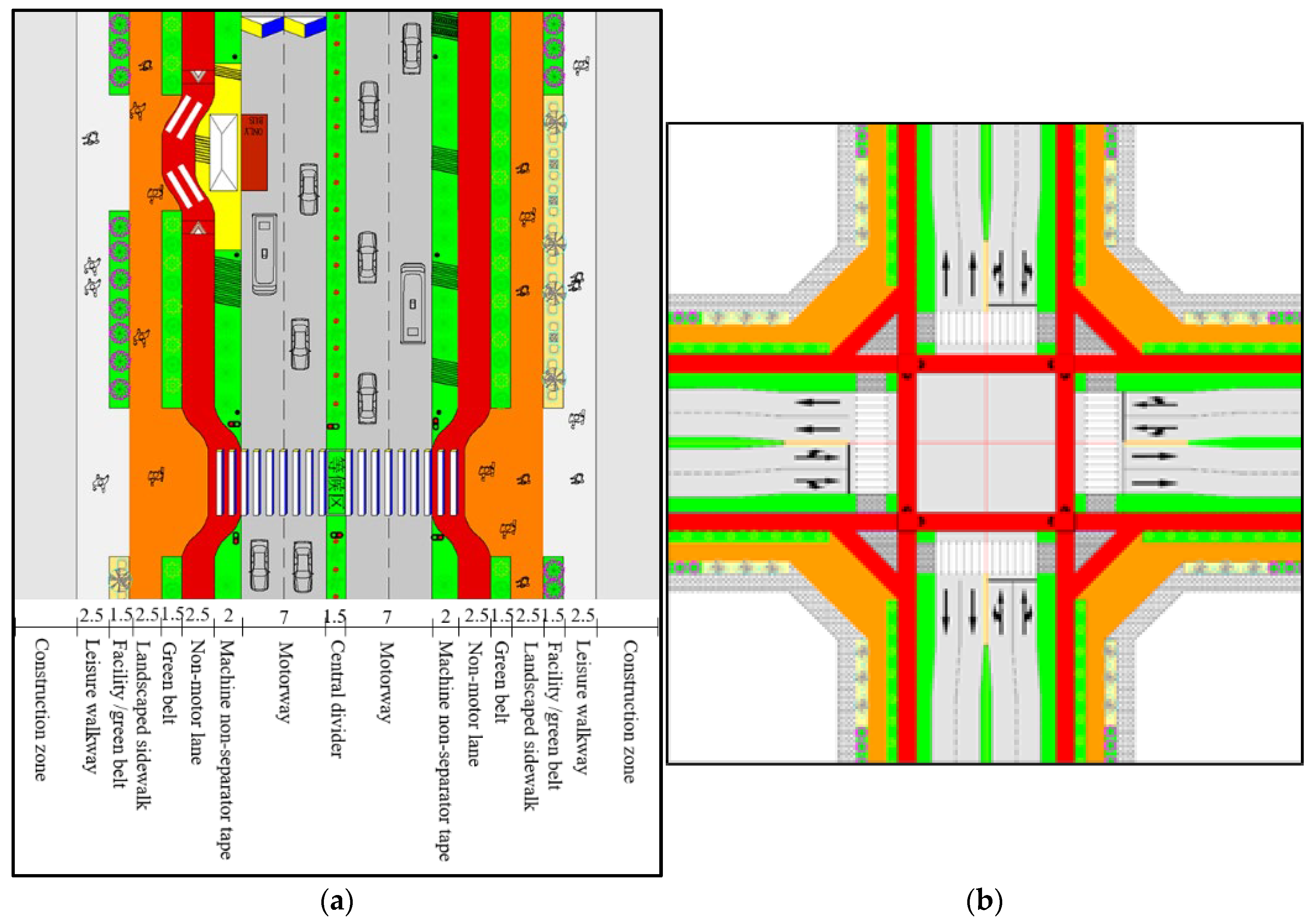

2.1. Traffic Design of Vital Street Section

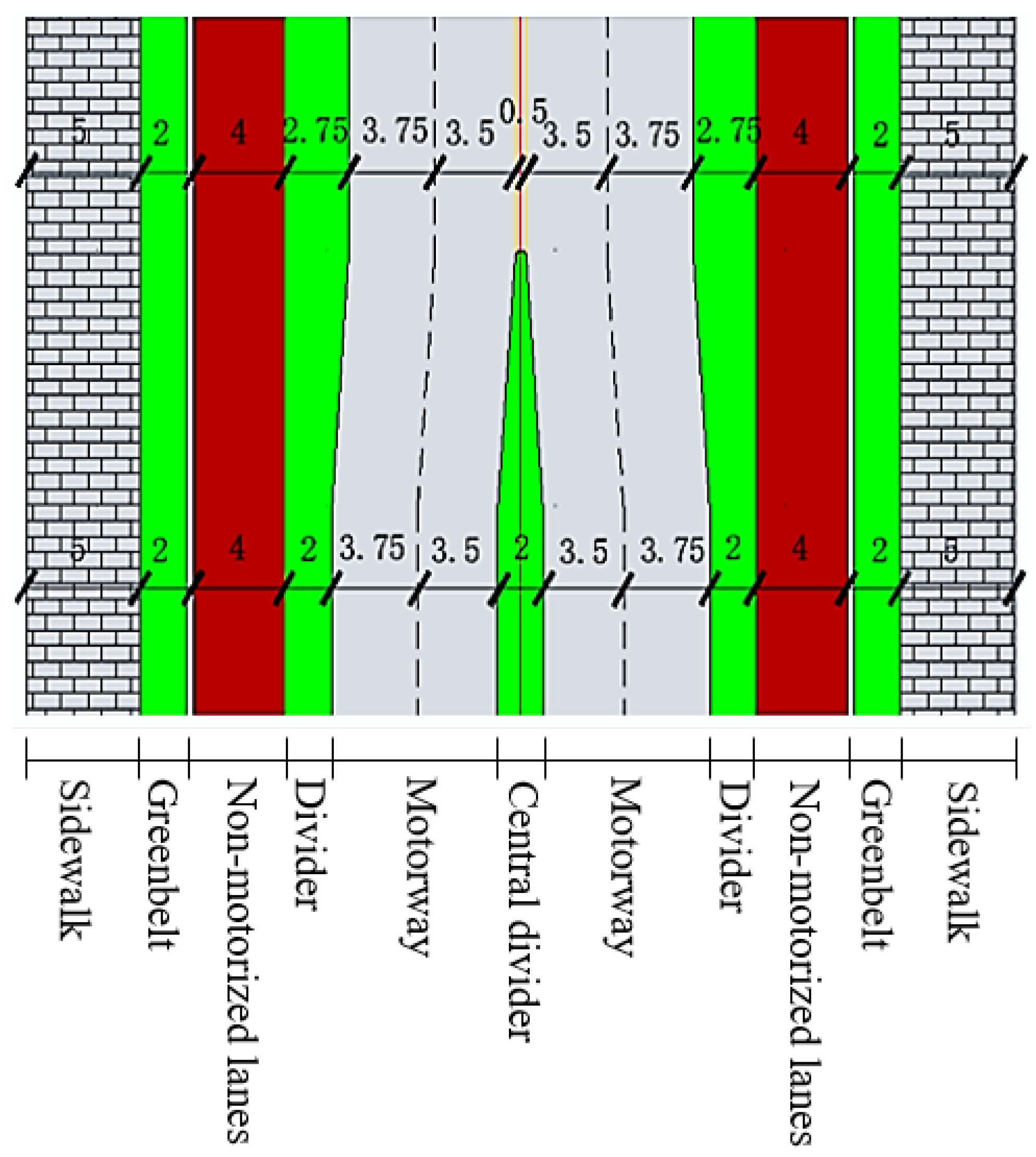

2.1.1. Road Interior Space Design

2.1.2. Walking and Activity Space Design

2.1.3. Ancillary Facilities Design

- Traffic facilities

- (1)

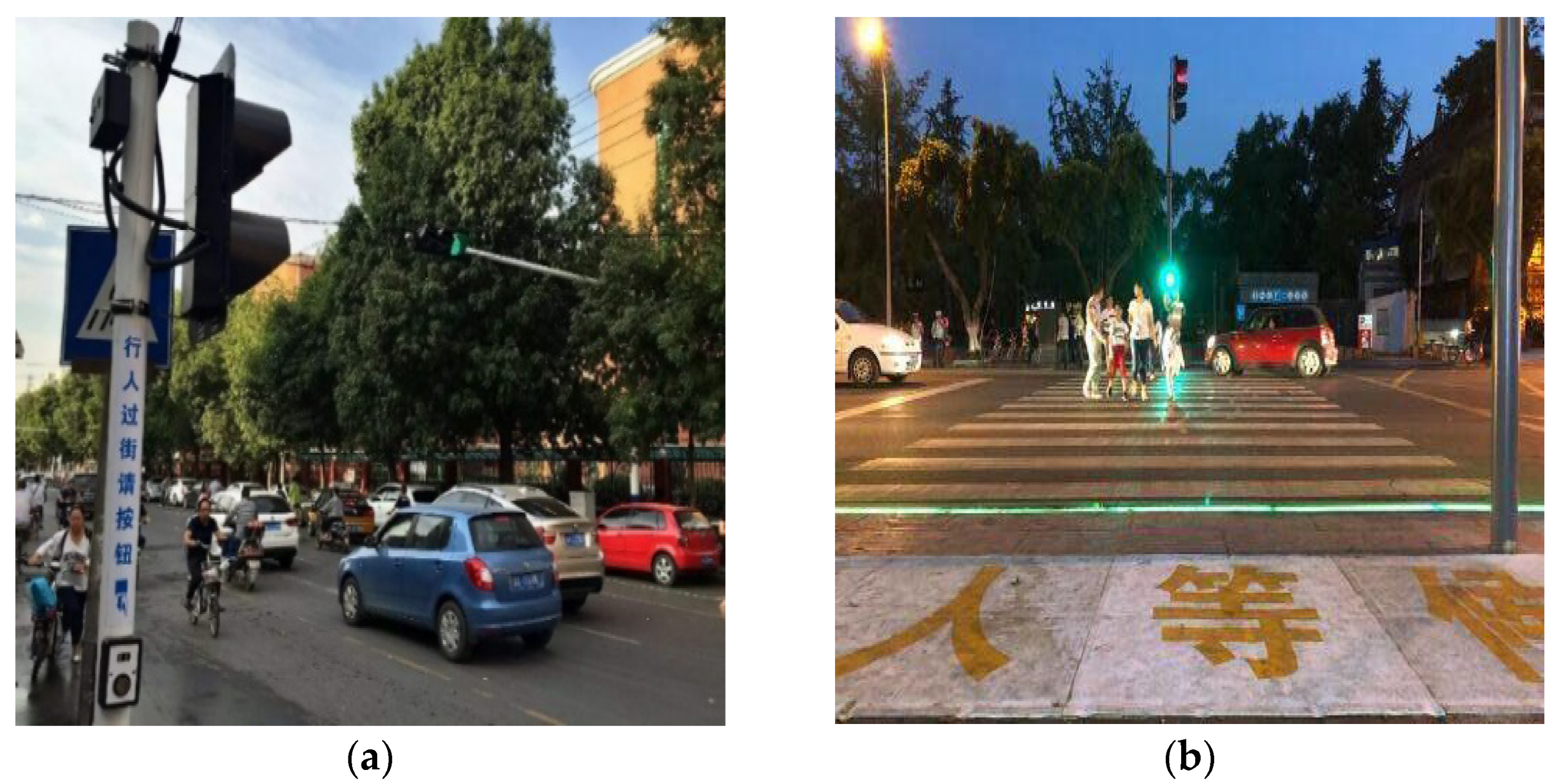

- Pedestrian crossing facilitiesThe cross section of the street was symmetrical. When the distance of pedestrians crossing the street at one time was equal or greater than 18 m, the central divider should be used to set up a safety island for two times. When non-motor vehicles crossed the street, the width of the safety island should not be less than 2 m. Set up crosswalk signal lights on pedestrian crossing safety islands [25]. The design scheme was shown in Figure 4, the curb of the non-motorized lane protrudes 2 m to the non-motorized zone, and the non-motorized zone was compressed. In order to guarantee the continuity of the non-motorized lane, the footpath also protruded 2 m.Figure 4. Design drawing of ancillary facilities of a vital street section.As shown in Figure 5, the pedestrian crossing traffic light should be set as touch type signal light, and the height of the pedestrian button should be within the range of 1.2 m to 1.5 m. At the same time, set up the sound of traffic lights to remind, the entrance of the crosswalk set up the ground LED light to remind, and kept synchronized with the crossing traffic lights, to prevent “phubs” playing mobile phones to ignore the traffic lights caused by the hidden dangers of crossing the street.Figure 5. Pedestrian crossing facilities. (a) Touch type signal lamp. (b) Floor LED reminder lamp.

- (2)

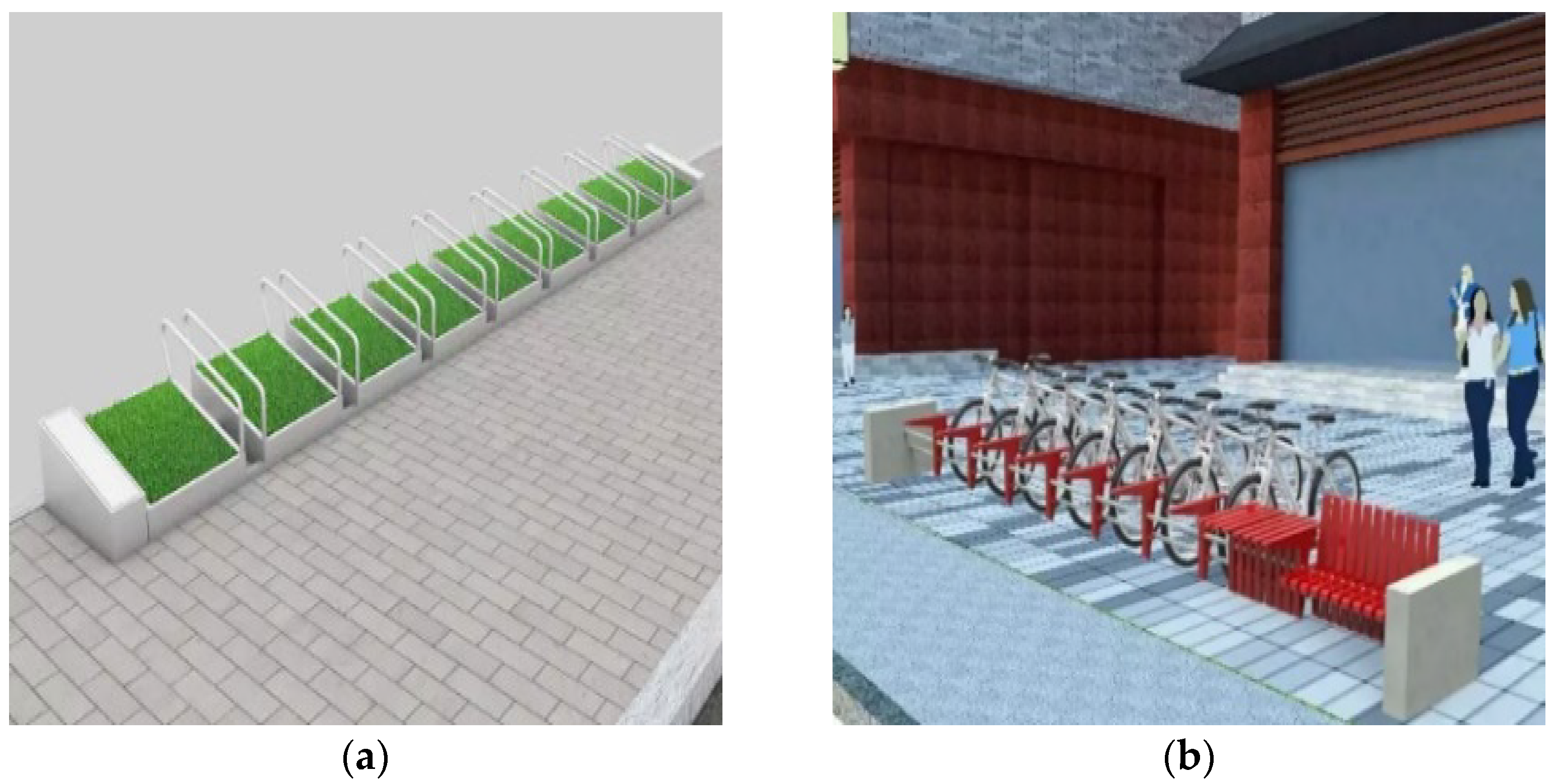

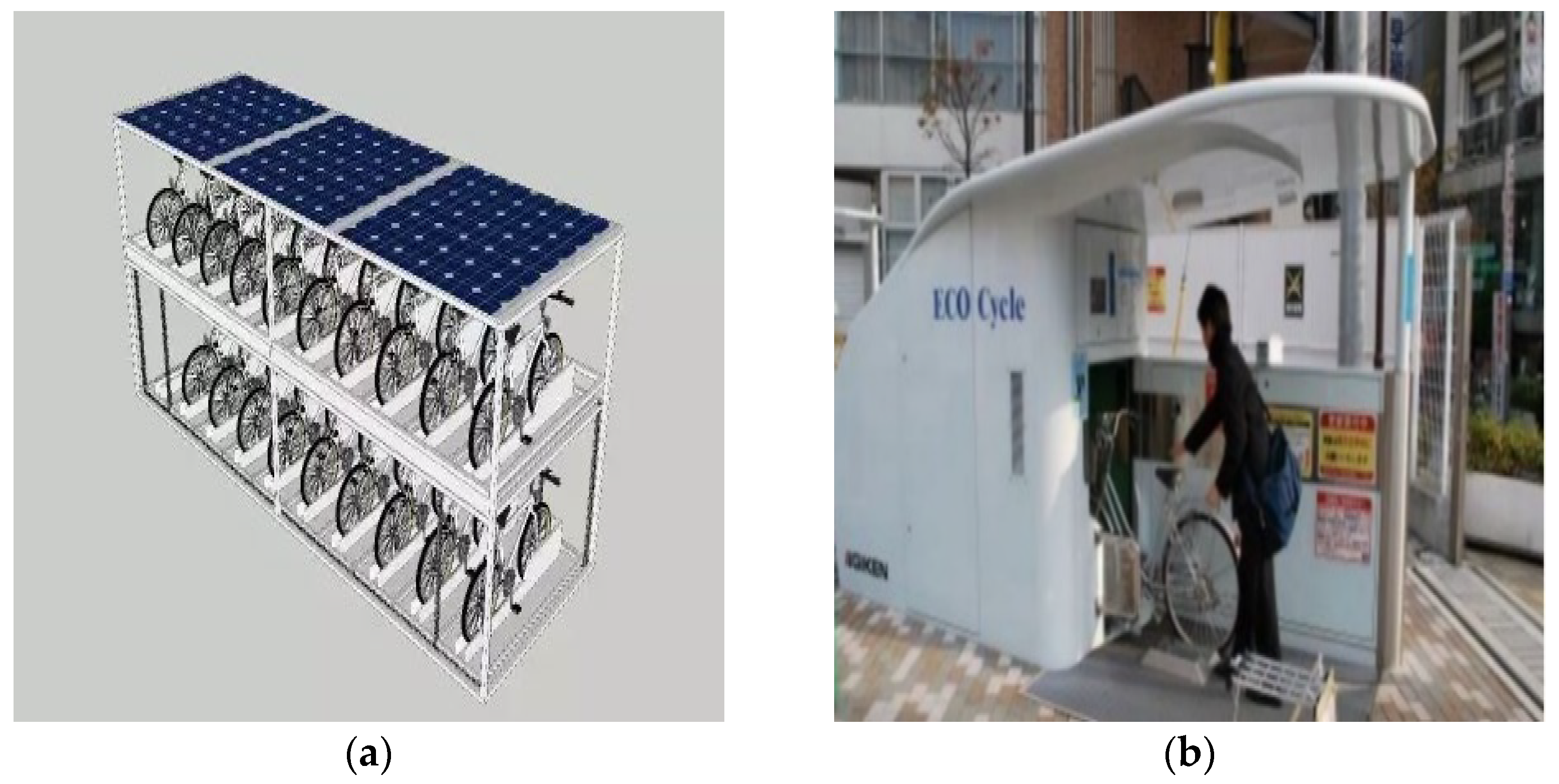

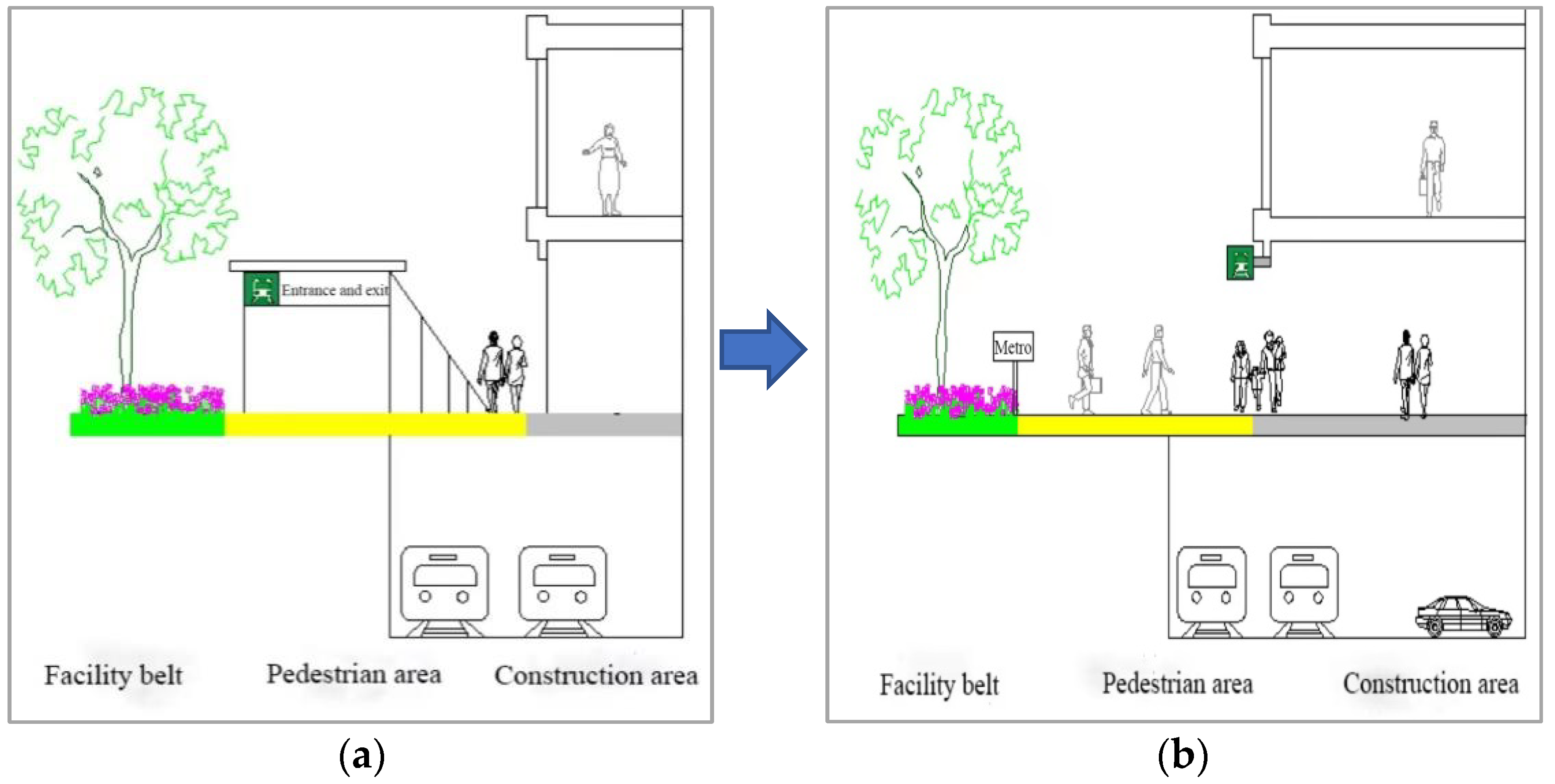

- Bicycle parking facilitiesBicycle parking spaces were set up in the space behind the separation zone for motor vehicles and non-motor vehicles and the bus station; a bicycle parking area was planned next to the subway station on the ground to facilitate the transfer between bicycles and subways (as shown in Figure 6).Figure 6. Layout of bicycle parking space. (a) Behind the separation zone for motor vehicles and non-motor vehicles and the bus station. (b) Next to the subway station.Figure 6. Layout of bicycle parking space. (a) Behind the separation zone for motor vehicles and non-motor vehicles and the bus station. (b) Next to the subway station.As shown in Figure 7, bicycle parking facilities could adopt landmark and easily identifiable road parking racks, one for each vehicle, which were easy to park neatly, strong wind resistance and novel.Figure 7. Bicycle parking rack. (a) Type one; (b) type two.For nodes with large street space, such as squares and parks, advanced ground and underground three-dimensional bicycle parking methods could be adopted, as shown in Figure 8.Figure 8. (a) Underground stereo bicycle parking mode; (b) ground three-dimensional bicycle parking mode.Figure 8. (a) Underground stereo bicycle parking mode; (b) ground three-dimensional bicycle parking mode.According to the layout characteristics of bicycle parking spaces in vital streets, roadside guardrail parking racks could be used for bicycle parking facilities near the machine non separation belt and subway stations. For bicycle parking facilities in the rear space of the bus shelter, the integrated design of the bus shelter and bicycle facilities could be used, as shown in Figure 9.Figure 9. Vital street bicycle parking facilities.

- (3)

- Motor vehicle parking facilitiesAs shown in Figure 10, make full use of the underground space, set the motor vehicle parking lot in the underground parking lot of large buildings, and set the subway station close to the ground floor of the building to form a “P + R” (parking and transfer) mode with the underground parking lot of the building, so as to facilitate the transfer between motor vehicles and subway.Figure 10. (a) Traditional parking facilities; (b) design of motor vehicle parking facilities in a vital street.Figure 10. (a) Traditional parking facilities; (b) design of motor vehicle parking facilities in a vital street.

- Service facilitiesStreet service facilities were mainly divided into municipal facilities and public leisure facilities. Municipal facilities mainly included street lights, signs, traffic lights, traffic electronic monitoring and so on; public leisure facilities mainly included leisure seats, cigarette butts dropping devices, mobile phone charging piles, shared charging treasure, etc.

- Landscape facilitiesIn places that affect the driver’s observation line of sight, such as pedestrian crossing, bicycle parking area of facility belt, etc., high trees should be cancelled, and seasonal flowers or green space could be set. In addition, street trees should be pruned regularly to avoid blocking street lights, street signs and signal lights. Add small shrubs in the green belt beside the pedestrian road to create rich levels of high, medium and low, and plant different varieties of street trees for different characteristic sections.

2.1.4. Interface Design of Buildings along the Street

- Space combination and layout design of buildings

- 2.

- Facade form design of buildings

- 3.

- Street architectural style design

- 4.

- Detailed design of building façade

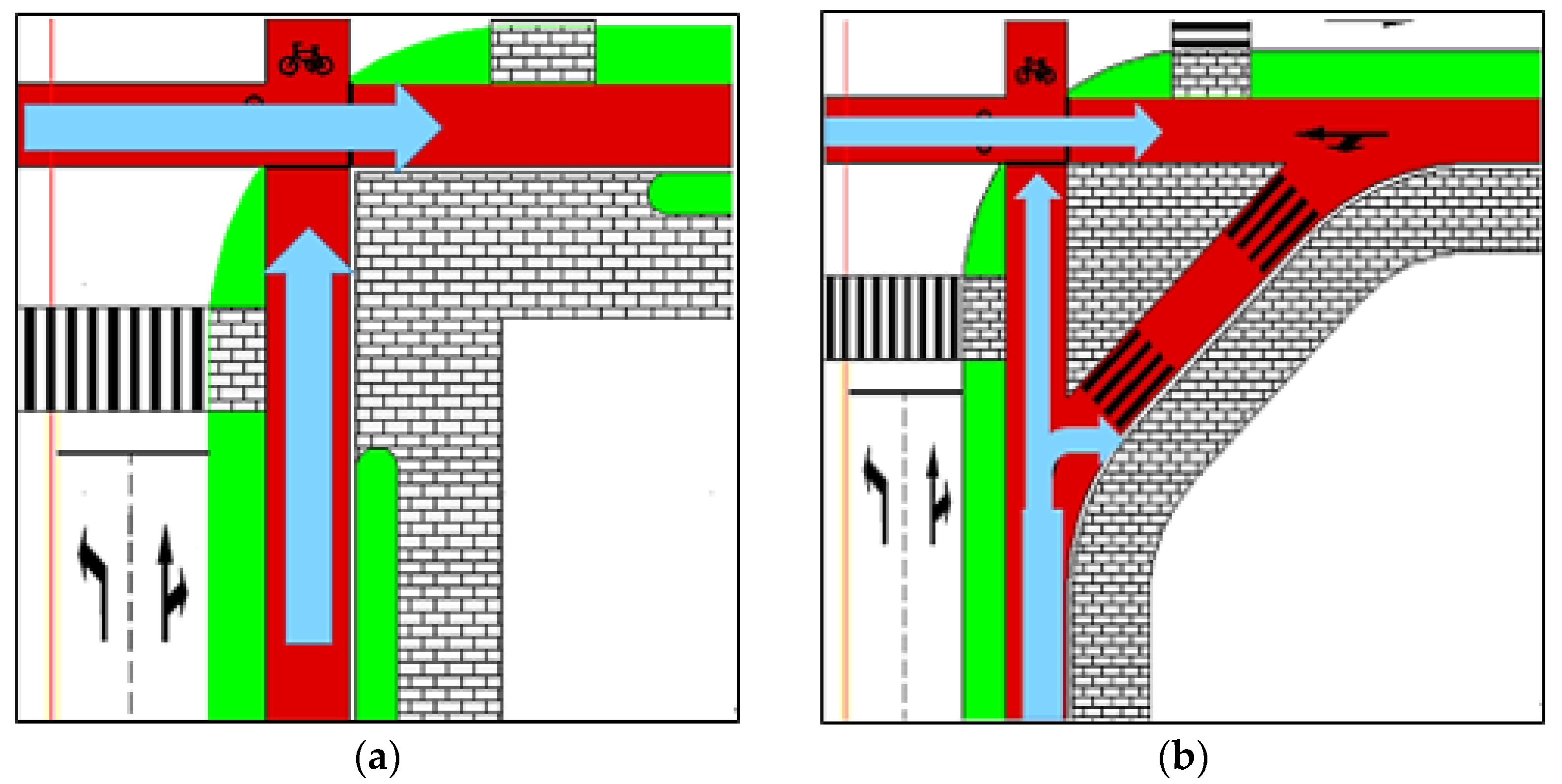

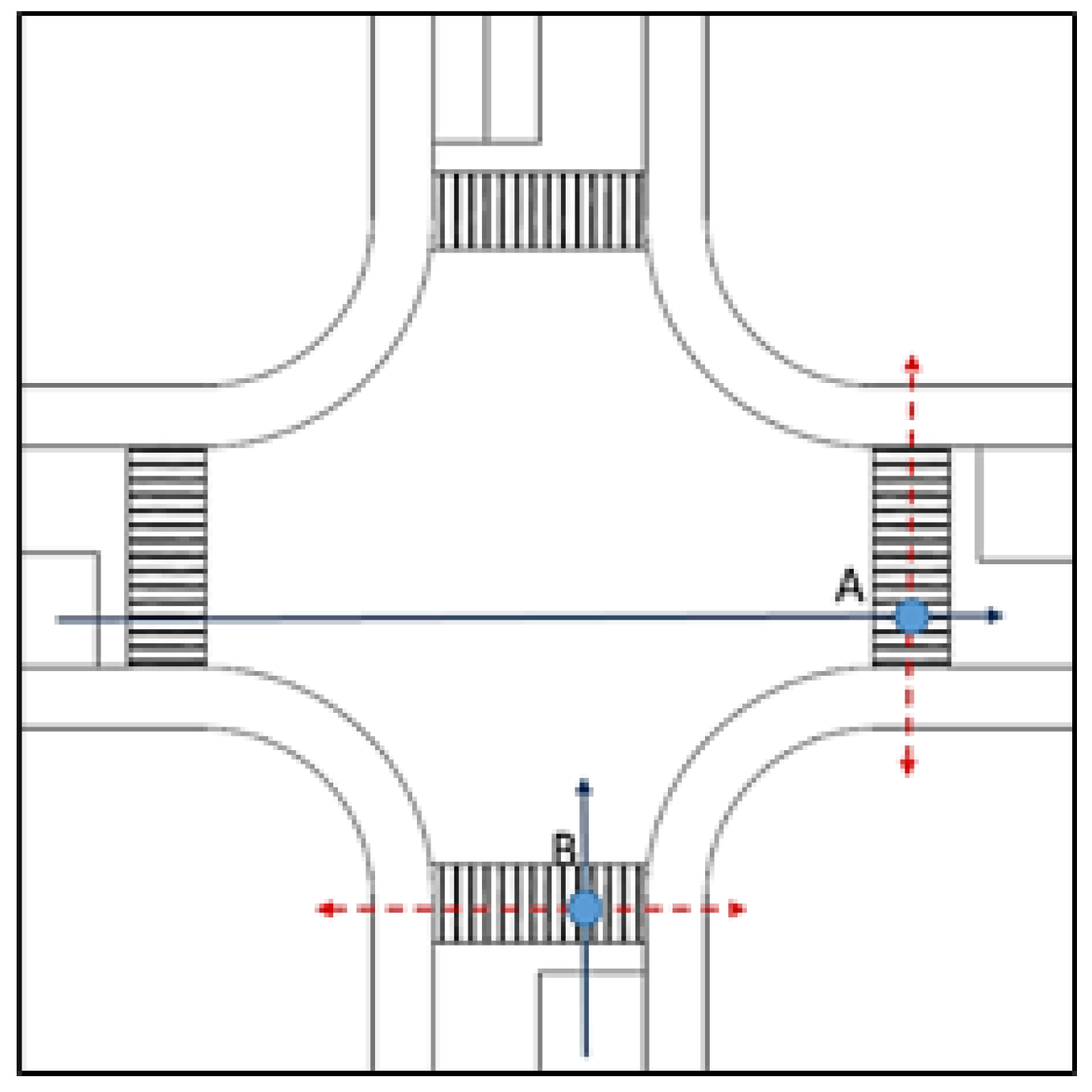

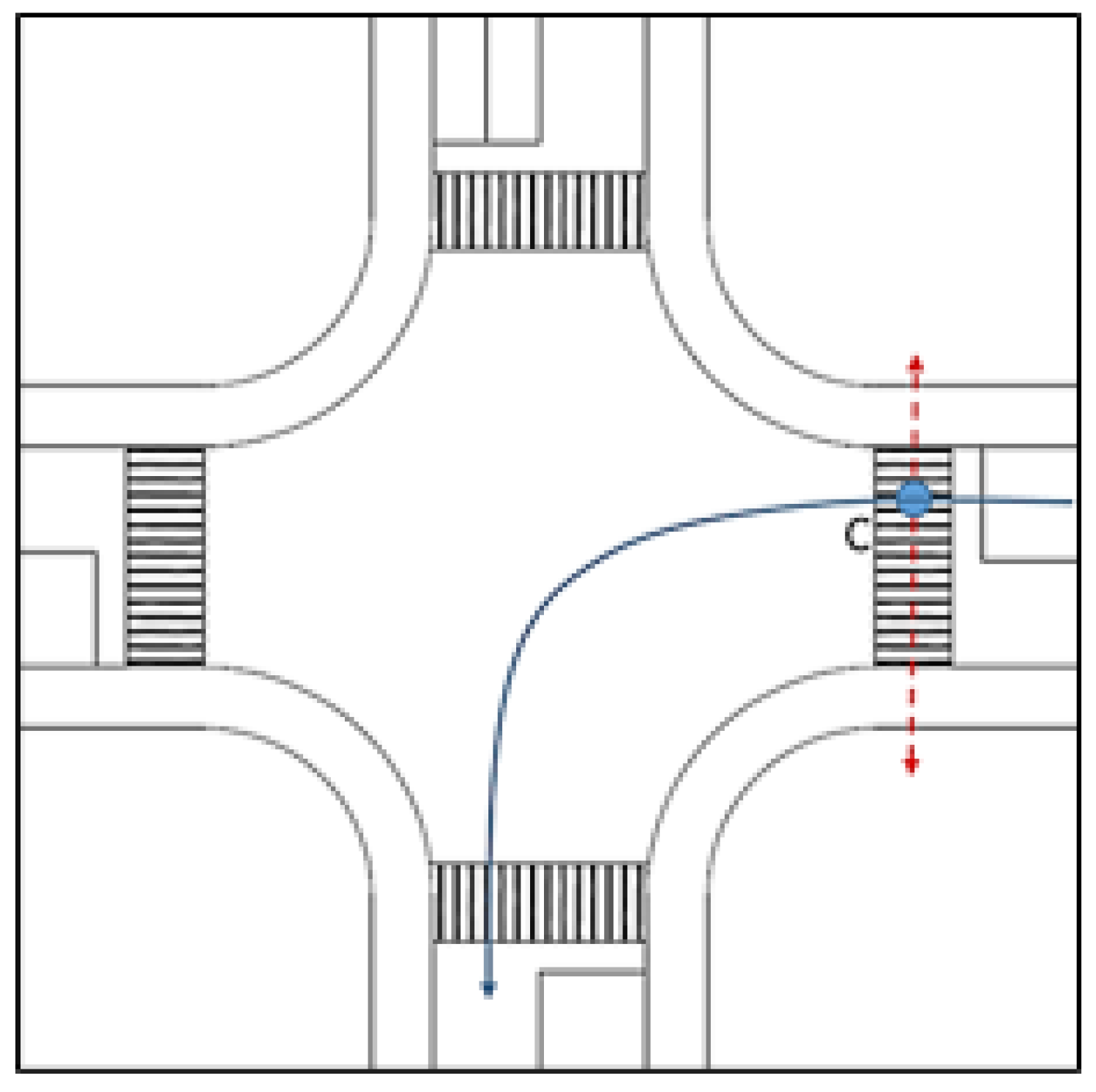

2.2. Traffic Design of Vital Street Intersection

2.2.1. Physical Space Design

- Vehicle

- 2.

- Non-Motor Vehicle

- 3.

- Walking and activity area

2.2.2. Traffic Organization Design

2.2.3. Ancillary Facilities Design

- Traffic facilities

- 2.

- Service facilities

- 3.

- Landscape facilities

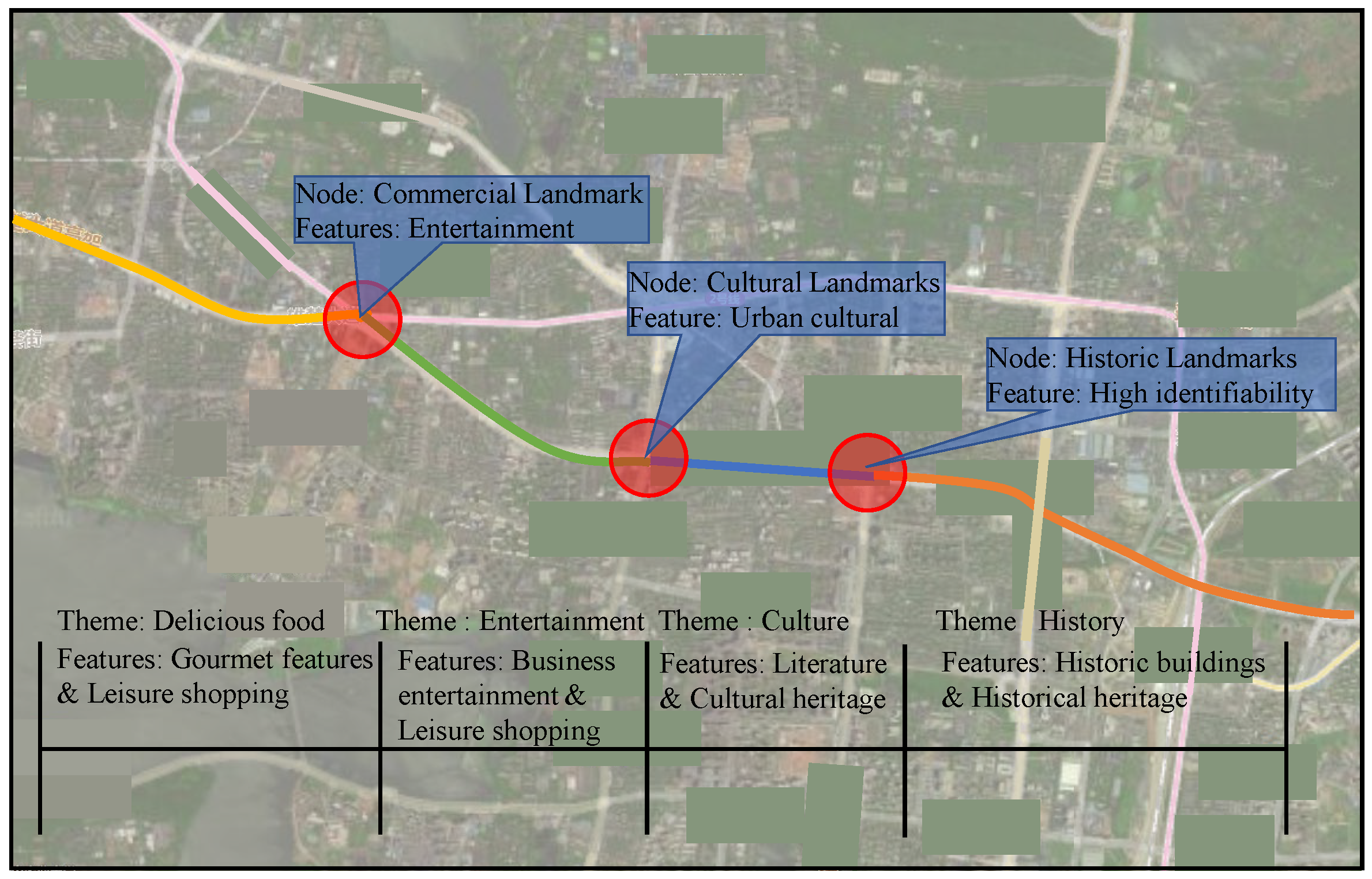

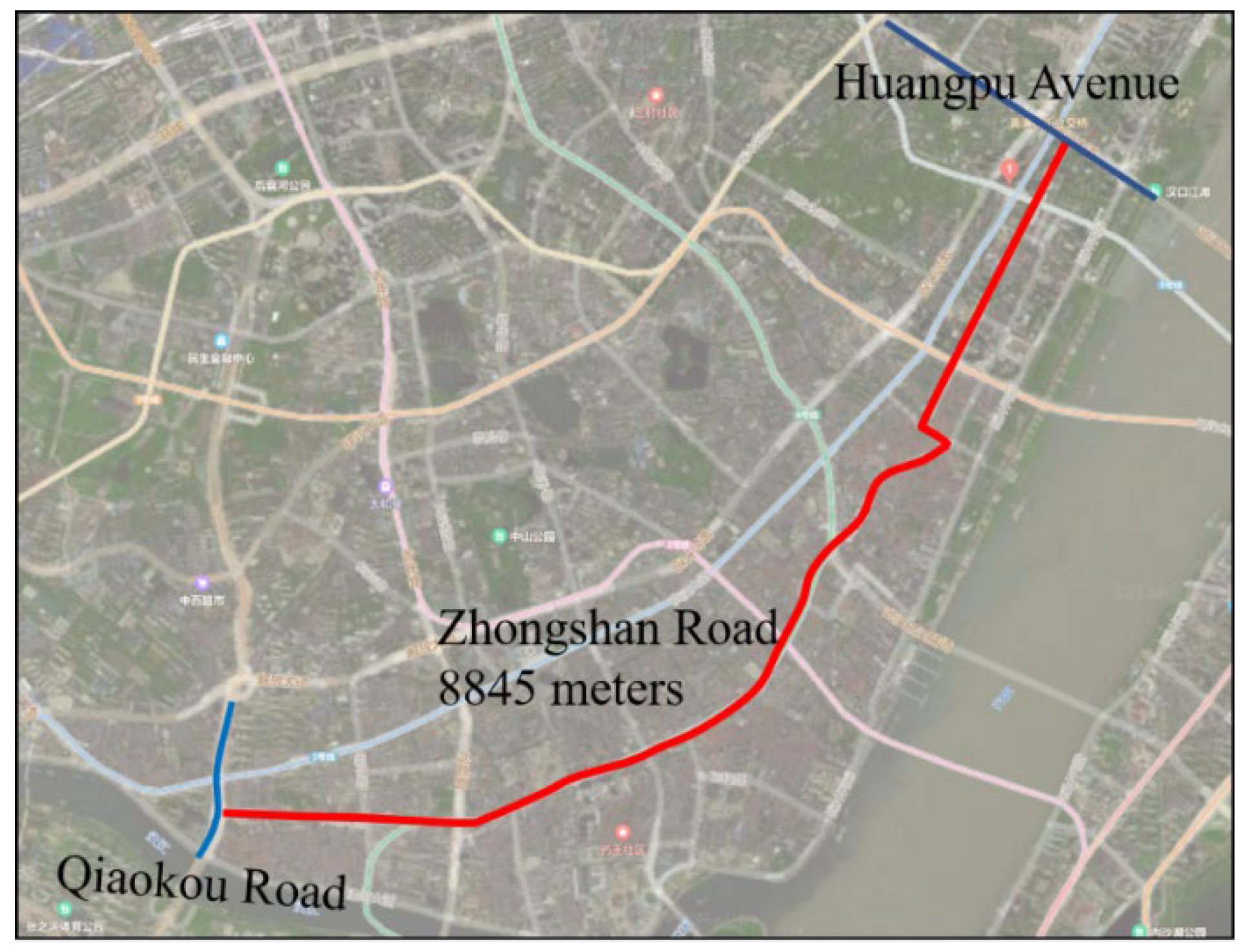

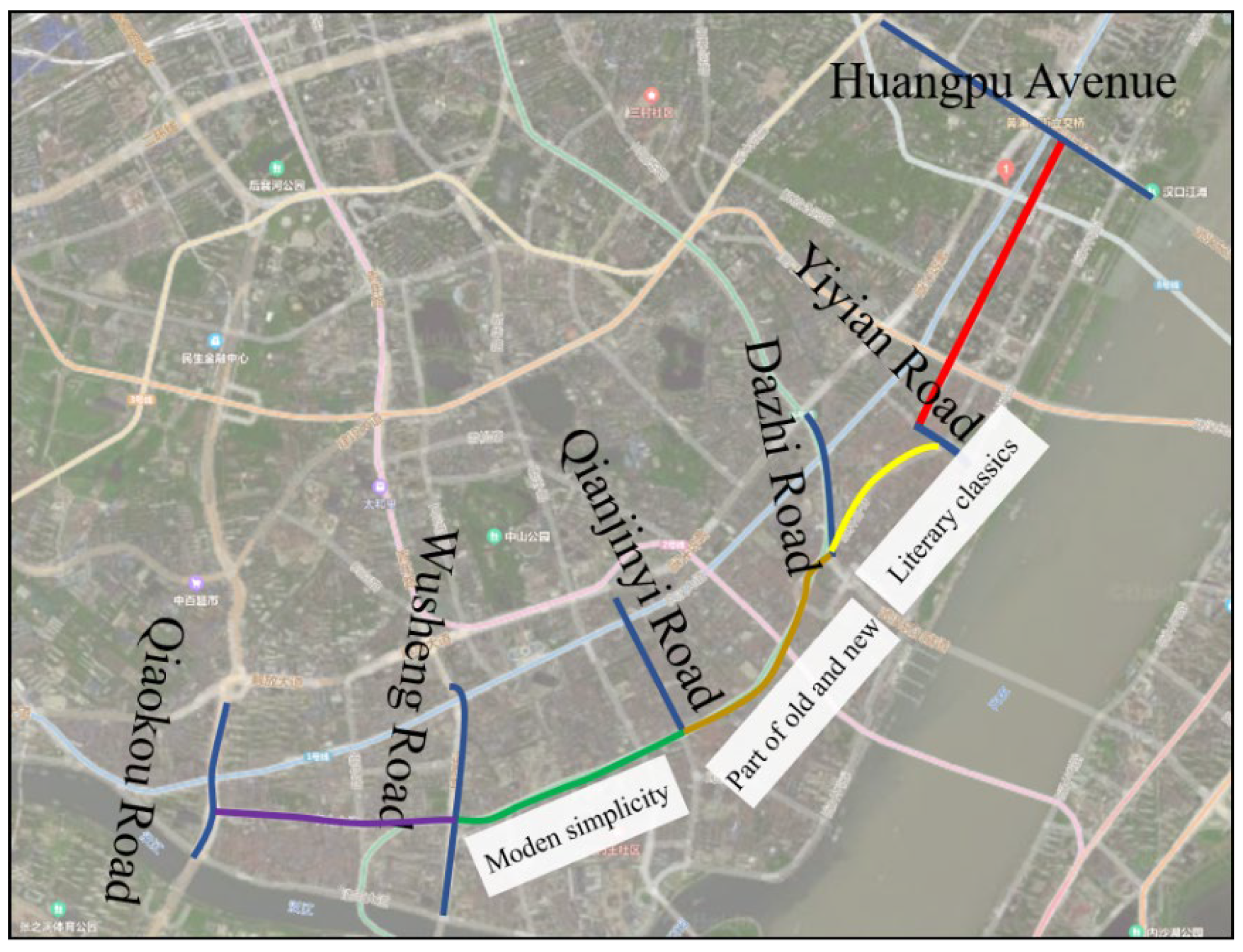

3. The Empirical Analysis

3.1. The Empirical Selection

3.1.1. The Empirical Generalizations

3.1.2. The Empirical Generalizations

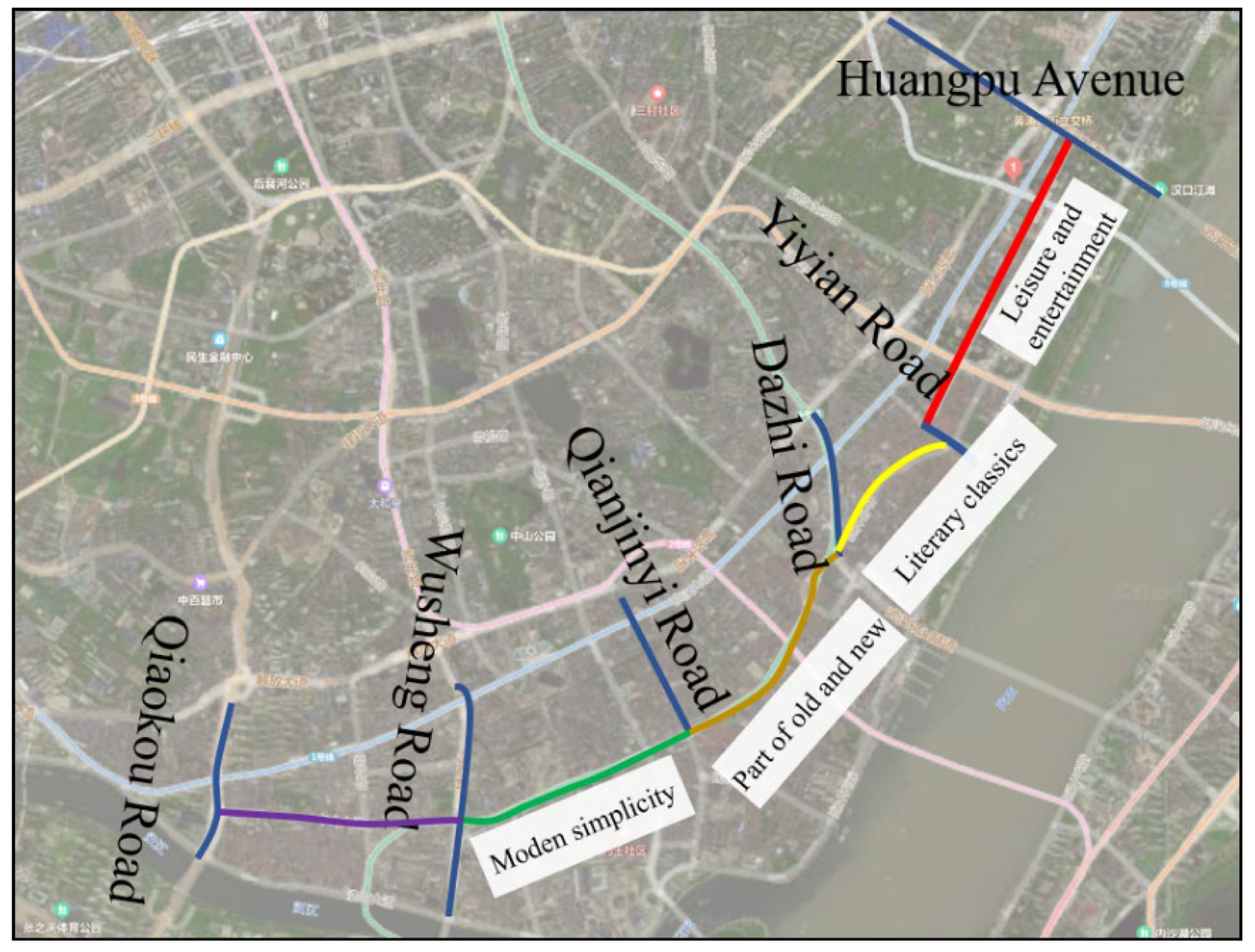

3.1.3. Traffic Development of Zhongshan Avenue in Wuhan City

- Motor traffic system

- 2.

- Rail transit system

- 3.

- Conventional bus system

- 4.

- Bicycle system

- 5.

- Walking system

3.2. Traffic Characteristics Analysis of Zhongshan Avenue in Wuhan City

3.2.1. Research Contents and Methods

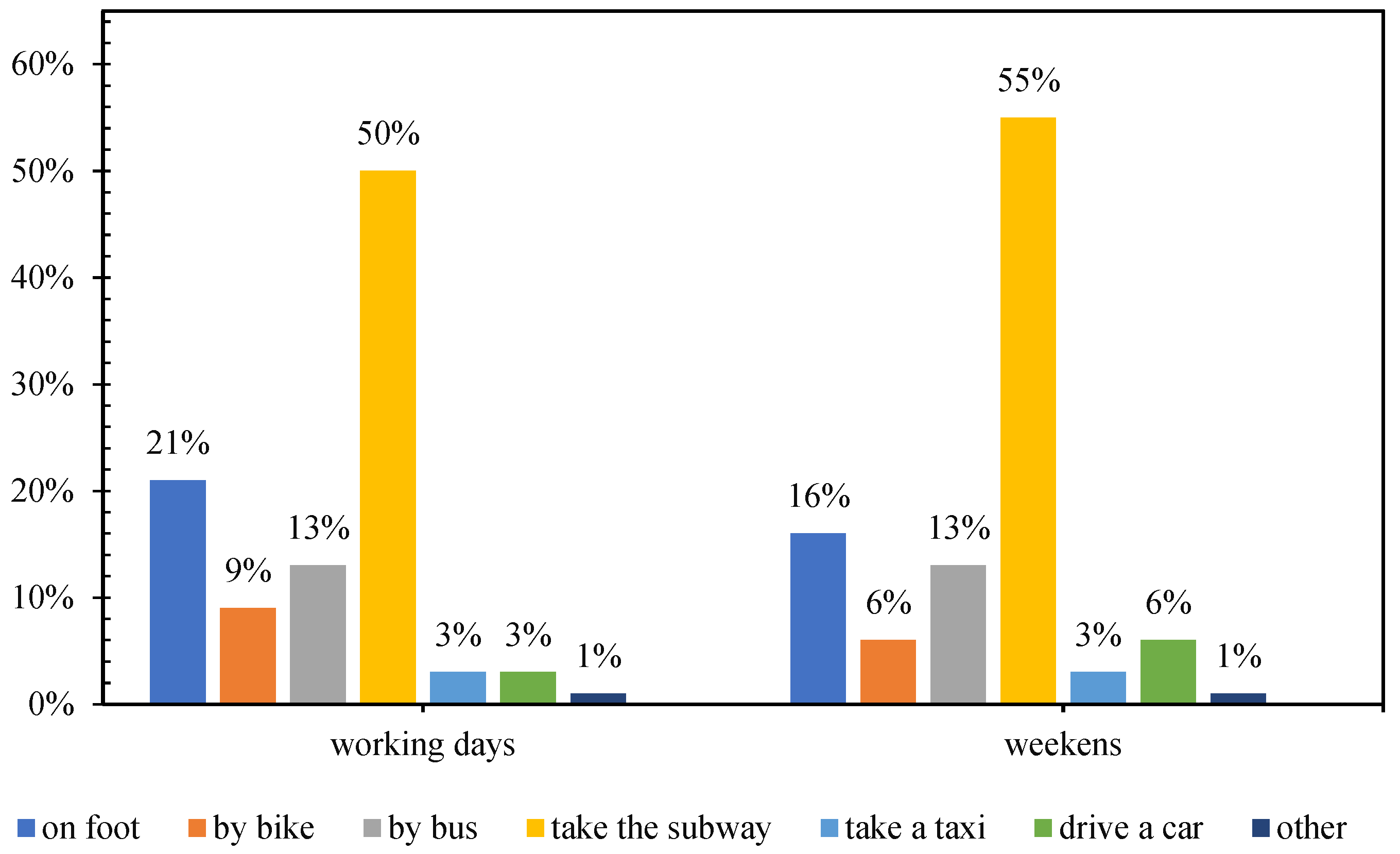

3.2.2. Survey Statistics and Traffic Characteristics Analysis

3.3. Traffic Design of Zhongshan Avenue in Wuhan City

4. Conclusions

- The basic idea of a vital street is being “people-oriented”. We concluded that the traffic connotations for a vital street lie in having an efficient, safe, healthy, and environment-friendly green traffic system and a good slow travel environment.

- The traffic design method for a vital street section was determined. According to the main characteristics of vital streets, combined with the design concept of being “people-oriented”, four aspects of design elements and specific design methods were discussed: road interior space, walking and activity space, auxiliary facilities, and street architectural interface.

- The traffic design method of the intersections of vital streets was determined, mainly from consideration of three parts of the key points and methods of design: physical space design, traffic organization design, and auxiliary facilities design

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Zhou, X.; Rana, M.P. Social benefits of urban green space: A conceptual framework of valuation and accessibility measurements. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2012, 23, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegetschweiler, K.T.; Vries, S.D.; Arnberger, A.; Bell, S.; Brennan, M.; Siter, N.; Olafsson, A.S.; Voigt, A.; Hunziker, M. Linking demand and supply factors in identifying cultural ecosystem services of urban green infrastructures: A review of European studies. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 21, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodriguez-Valencia, A.; Ortiz-Ramirez, H.A. Understanding Green Street Design: Evidence from Three Cases in the U.S. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenscroft, N. The Vitality and Viability of Town Centres. Urban Stud. 2015, 37, 2533–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Chodron Drolma, S.; Zhang, X.; Liang, J.; Jiang, H.; Xu, J.; Ni, T. An investigation of the visual features of urban street vitality using a convolutional neural network. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 23, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, C. Happy City: Transforming Our Lives through Urban Design. Civ. Eng. 2014, 84, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cranshaw, J.; Schwartz, R.; Hong, J.I.; Sadeh, N. The Livehoods Project: Utilizing Social Media to Understand the Dynamics of a City. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2012, 6, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Feick, R.; Robertson, C. A multi-scale approach to exploring urban places in geotagged photographs. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2015, 53, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.W. Measuring Streetscape Design for Livability Using Spatial Data and Methods; The University of Vermont and State Agricultural College: Burlington, VT, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S. Imagining the Future City: London 2062. Ubiquity Press: 2013. Available online: https://www.ubiquitypress.com/site/chapters/e/10.5334/bag.u/ (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Nai, W. Study on the Influence of Physical Space Environment on Street Vitality of Living Street. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zarin, S.Z.; Niroomand, M.; Heidari, A.A. Physical and Social Aspects of Vitality Case Study: Traditional Street and Modern Street in Tehran. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, X.; Xu, X.; Guan, P.; Ren, Y.; Ning, X. The cause and evolution of urban street vitality under the time dimension:Nine cases streets in Nanjing city, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Samvati, S.; Nikookhooy, M.; Saiedizadi, M. The Role of Vitality and Viability of Urban Streets in Enhancement the Quality of Pedestrian–Oriented Urban Venues (Case Study: Buali Sina Street, Hamedan, Iran). J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 554–561. [Google Scholar]

- Yj, A.; Yun, H.; Ml, D.; Yu, Y. Street vitality and built environment features: A data-informed approach from fourteen Chinese cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 79, 103724. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, T. The Dynamic Development of Urban Public Space. Urban Plan. Forum 2012, 5, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, L.; Xiao, L. Redevelopment of Urban Public Space: A Review of Urban Street Design Manuals in the World. Urban Transp. China 2014, 12, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Yue, W.; Xie, J.; Yang, L.; Jie, Z. Return to Human-oriented Streets:The New Trend of Street Design Manual Development in the World Cities and Implications for Chinese cities. Urban Plan. Int. 2012, 27, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, W.W.; Lokman, N.I.S.; Hasan, R.; Hassan, K.; Ramlee, N.; Nasir, M.M.; Yeo, L.B.; Gul, Y.; Bakar, K.A.A. The implication of street network design for walkability: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 881, 012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, P. Urban Street Design Based on Spatial Experience. J. Landsc. Res. 2020, 12, 117–119. [Google Scholar]

- Zoppi, C.; Mereu, A. Perceived urban quality of the historic centers: A study concerning the city of Cagliari (Italy). Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Apilánez, B.; Karimi, K.; García-Camacha, I.; Martín, R. Shared space streets: Design, user perception and performance. Urban Des. Int. 2017, 22, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Traffic Management Research Institute, Ministry of Public Security. Specification for Setting and Installation of Road Traffic Signal Lights; General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People′s Republic of China; Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2016; Volume GB 14886-2016, p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Tongji University. The code for Urban Road intersection planning. In Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, PRC.; General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People′s Republic of China; Tongji University: Shanghai, China, 2010; Volume GB 50647-2011, p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Hanser, A. Street Politics: Street Vendors and Urban Governance in China. China Q. 2016, 226, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Travel Purpose | Go and from Work | Entertainment | To Visit Friends and Relatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| weekdays | 22% | 69% | 9% |

| weekends | 18% | 68% | 14% |

| Environmental Improvement Proposals | Set Up Non-Motor Vehicle Lane | Additional Public Bicycle Spots | Set the Bike Parking Position | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| weekdays | 44% | 25% | 27% | 4% |

| weekends | 46% | 27% | 23% | 4% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Tan, C.; Li, M.; Gu, D.; Wang, H. Research on Traffic Design of Urban Vital Streets. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116468

Wang F, Tan C, Li M, Gu D, Wang H. Research on Traffic Design of Urban Vital Streets. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116468

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fu, Chang Tan, Miaohan Li, Dengjun Gu, and Huini Wang. 2022. "Research on Traffic Design of Urban Vital Streets" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116468

APA StyleWang, F., Tan, C., Li, M., Gu, D., & Wang, H. (2022). Research on Traffic Design of Urban Vital Streets. Sustainability, 14(11), 6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116468