1. Introduction

There is a small but growing ‘recognition of the relationship between peace and sustainability in both academic and policy circles’ [

1]. In this article, I aim to show that nonviolence is an essential element of environmental sustainability and the cultivation of peace, which are two key concepts in the United Nations’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: ‘Transforming our world’. After a brief discussion of the 2030 Agenda, I will define the terms ‘nonviolence’ and ‘sustainability’ and show the connections between the two.

I will then describe a number of pivotal Australian nonviolent environmental campaigns, demonstrating how without them much more environmental damage and global warming would have occurred. Next, I define militarism and the industries that are part of it and examine its environmental footprint and demonstrate that reducing this footprint is essential for global sustainability. I will describe some nonviolent campaigns against war and militarism as well.

The footprint of militarism can be reduced by making militaries more environmentally-friendly, but a more fundamental long-term solution is to reduce militarism and the need for it by replacing it with nonviolent methods of defence and regime change.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper is reliant on a nonviolence theory framework within Galtung’s notion of ‘positive peace’ [

2,

3], with the analysis of the environmental campaigns resulting from the triangulation of mixed methods fieldwork that utilize participant–observer research supported by document analysis and literature reviews. Participant–observer research is a qualitative methodology which, while having some flaws and biases, enables unique ethno-inductive insights that may not be obtainable by researchers based in outside movements due to issues of trust and because of movement complexity [

4]. Furthermore, these case studies result from longitudinal action research by this author and his colleagues (such as Bob Boughton) and Ph.D. students (such as Aidan Ricketts and Vanessa Bible) across a period of forty years following major Australian environmental campaigns. As movement insiders and emic researchers with valuable contacts and experience in the leadership and intelligentsia of national movements, they have been able to develop deep-seated subaltern understandings of the dynamics and evolution of such movements which shallower, extra-movement research would struggle to replicate.

This paper also examines the work of numerous scholars and non-government organisations who have explored various aspects of pollution and resource depletion caused by war and militarism and presents an overview of their findings. It also describes how the case studies sit within an international history of effective nonviolent action even against ruthless regimes, which suggests that it could be used to replace violent methods of national defence and regime change. In doing so, it draws together disparate elements to make a cohesive argument about the relationship between environmental nonviolent action, nonviolent action as a whole, and positive peace. The uniqueness of this exploratory approach lies in both the emic (insider) insights into environmental nonviolent action in Australia and the weaving of disparate themes into a comprehensive narrative that offers both practical and theoretical pathways towards positive peace. While potentially useful to researchers and policymakers, it is primarily aimed at an activist or potential activist readership.

3. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

The 2030 Agenda of the United Nations is an initiative of the Sustainable Development section of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs. It seeks ‘to build on the Millennium Development Goals and complete what these did not achieve’ [

5]. The 2030 Agenda forcefully argues that there is a close and intertwined relationship between the environment and peace. On the former it urges ‘taking urgent action on climate change’, while on the latter, it states: ‘We are determined to foster peaceful, just, and inclusive societies which are free from fear and violence. There can be no sustainable development without peace and no peace without sustainable development’ [

5].

It further argues that the 17 Sustainable Development Goals and 169 targets are ‘integrated and indivisible and balance the three dimensions of sustainable development: the economic, social, and environmental’ [

5]. It is ‘a plan of action for people, planet, and prosperity. It also seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom. We recognise that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for sustainable development. All countries and all stakeholders acting in collaborative partnership will implement this plan. We are resolved to free the human race from the tyranny of poverty and want and to heal and secure our planet’ [

5].

As noted above, this is a plan for action rather than to ‘greenwash’ and be business-as-usual for environmentally-damaging corporations or bureaucratic obfuscation by governments: ‘We are determined to take the bold and transformative steps which are urgently needed to shift the world onto a sustainable and resilient path’ [

5]. This article suggests that nonviolent methods of resistance to environmental damage and depletion, and the replacement of war and militarism with nonviolent methods, constitute such bold and transformative steps to avert climate catastrophe, as depicted in

Figure 1.

4. Sustainability

In this paper, I use the term ‘sustainability’ in the sense of being able to continue within the limits of the environment—i.e., minimising the use of non-renewable resources, replenishing ecosystems at the same or, preferably, greater rate than their depletion, minimising pollution and rehabilitating past pollution, reducing greenhouse gas emissions to (at least) net zero, and preferably establishing carbon negative societies. This definition arises out of the 1987 United Nations Brundtland Commission, where environmental concerns led to new approaches towards and attempted curbs on unregulated or irresponsible development, with the UN continuing to argue that ‘sustainable development requires an integrated approach that takes into consideration environmental concerns along with economic development’ [

6]. The National Geographic Society’s definition is even more emphatically environmental: ‘Sustainability is the practice of using natural resources responsibly today, so they are available for future generations tomorrow’ [

7].

Some prefer the term ‘environmental sustainability’ to distinguish it from other forms of sustainability, such as social and economic sustainability, as described by Sharifi and Simangan [

1] and Pinckney [

8]. In any case, however, environmental sustainability is inextricable from these other forms of sustainability because deficits in the latter will almost certainly impact environmental sustainability—for example, where extremes of poverty lead to the over-exploitation of natural resources such as forests and fish. In Peace Studies theory, this closely correlates with Galtung’s inter-connected triangle of direct (including ecological) violence, structural violence, and cultural violence, the opposite of which is positive peace, which minimises all three forms of violence, holistically addresses the root causes of conflicts, and therefore leads to the sustainability of peace [

2,

3]. Following Gandhi, this concept argues that violent methods of conflict resolution and environmental production are counter-productive; instead, societies should attempt to break

all cycles of violence.

A recent Peace Studies student at the University of New England, Australia gives an example from her environmental group of this connectivity and holistic vision:

‘While it has many of the features of Landcare, and we are affiliated with the Landcare movement, GLENRAC [the Glen Innes Natural Resource Advisory Committee] is actually more than environmental projects. It recognizes that if we are going to achieve any shift towards sustainability, we all need to work together. Some of that together-work is environmental, some is economic/financial, and some of that work is about building a resilient community. During the 2018–2020 drought and bushfires, for example, GLENRAC’s environmental projects took more of a back-seat to landholder support and community welfare activities, (although we did still plant over 15,000 trees in the Spring of 2019)’ (Julie Firth online forum post, 21 May 2021).

Simangan et al. examine the positive peace–sustainability nexus through examining all aspects of sustainability [

9]. This paper, however, focuses on environmental sustainability for three reasons: it has traditionally been seen since the Brundtland Commission as the cornerstone of sustainability; the climate emergency is the globe’s most pressing crisis according to international bodies such as the World Health Organisation [

10]; and nonviolent environmental action has been this author’s primary research focus for forty years.

Sharifi and Simangan argue persuasively that ‘the environment is the missing link in existing positive peace indicators for achieving a more holistic peace relevant to our changing planet’ [

1]. This is a valid argument that should be accepted, but there is another notable missing link in the absence of nonviolence from positive peace indicators, such as the Institute of Economics and Peace’s Positive Peace Index and its eight pillars. While the model is generally sound, particularly if environmental sustainability is added as a pillar or at least made more explicit, there is surprisingly little about peace infrastructure [

11] or embedded nonviolent practices for waging conflict. Their eighth pillar, well-functioning government, could include peace infrastructure, such as through peace curricula embedded in educational institutions, and could include nonviolent civilian-based defence, but is unlikely to embrace nonviolence generally because it is often regarded by governments as a nuisance at best and a threat at worst [

12].

Sustainability and nonviolence have long had a connection, with activists often citing a desire for sustainable societies being their impetus for engaging in nonviolent environmental action, such as blockading inappropriate dams, old-growth logging, and new fossil fuel projects, or engaging in ‘guerilla gardening’ [

13]. Environmentalism and anti-war activism have also long been closely connected, as exemplified in Australian campaigns against uranium mining at Roxby Down and Jabiluka, which were over concerns about environmental damage as well as worries that uranium mining adds to stockpiles of nuclear material, thereby increasing the likelihood of governments or terrorists using it for nuclear weapons [

14,

15]. This coalition of movements has been termed the ‘eco-pax movement’ [

16].

5. Nonviolence

Nonviolence, according to Kurt Schock, is ‘an active process of bringing political, economic, social, emotional, or moral pressure to bear in the wielding of power in contentious interactions between collective actors’ [

17]. Physical violence or the threat of physical violence against human beings are to be avoided, and nonviolence is usually defined as operating outside the bounds of institutionalised political channels, although a more widespread understanding is of any human processes of social change or resistance that do not involve violence. In this vein, Roland Bleiker argues that seemingly undirected changes to the discourses and narratives of societies have been the root causes of the nonviolent demise of many 20th century regimes, such as communist East Germany and the USSR; dissent and resistance, therefore, are not just ‘mass uprisings and other heroic acts of defiance … [but are] located in countless non-heroic practices that make up the realm of the everyday and its multiple connections with contemporary global life’ [

18].

Nonviolence, therefore, is much more than just ‘not violent’. The Indian term

satyagraha or ‘truth force’ [

19] is more appropriate but lesser known, as it includes the many things it

is rather than

is not. Nonviolence involves acts of omission—i.e., a refusal to perform acts usually expected of people—and acts of commission—i.e., performing acts people usually don’t perform, are not expected to perform, or which are illegal. According to Gene Sharp [

20], it consists of three main categories:

protest and persuasion (e.g., rallies)

non-cooperation (e.g., boycotts and strikes)

nonviolent intervention (e.g., blockades).

It is a praxis that is widely used and has achieved some remarkable successes, such as the overthrow of numerous dictatorships, oppressive regimes, and police states [

21,

22]. It has been used widely to preserve ecosystems and resist oppressive systems such as patriarchy and racism [

23,

24].

It is not always used under the name of nonviolence. As Pam McAllister observes, ‘nonviolent actions were used long before the word nonviolence was first used in print in 1923 by Clarence Marsh Case in

Nonviolent Coercion: A Study in Methods of Social Pressure’ [

25]. It may not even recognized as such by its practitioners, and its successes have often been put down to such nebulous movers as ‘people power’, which supposedly rises spontaneously, creates major change, and then disappears again [

26]. The end of the Soviet empire, for example, was thought by many—perhaps even most people—to be impossible until it actually occurred, and then it was said to have been inevitable, the result of some inexorable eruption of ‘people power’ caused by mechanistic forces. Nevertheless, behind such monumental change is usually people with some grasp of the basic principles of nonviolent action, often based on historical campaigns. Examples include 1960s US civil rights activists such as James Lawson and Martin Luther King, Jr., learning from Gandhi’s satyagrahic campaigns [

21], who then inspired 1970s Australian Aboriginal land rights protesters [

27,

28] and 1980s anti-apartheid activists. Serbian protesters learned from these earlier campaigns [

29] and then supported Arab Spring activists through organisations such as the Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS), which is based in Belgrade [

30].

Despite these movements and others, such as the suffragette movement, having major influences on the world in the 20th century, there is a comparative paucity of literature systematically examining their dynamics. Although school curricula are full of histories of the world wars [

31], bookshops are crammed with military histories, and millions are poured into war memorials [

32], far less energy and resources go towards remembering nonviolent activists and the techniques they use or analysing the movements to discover the most effective mechanisms.

Nevertheless, the ancient and venerable history of nonviolence is finally seeing the light of day after centuries and even millennia of the domination of history by military perspectives. Examples include books such as Gene Sharp’s

The Politics of Nonviolent Action [

20], Howard Clark’s

People Power: Unarmed Resistance and Global Solidarity [

33], and Tim Gee’s

CounterPower:

Making Change Happen [

34]; films such as

Gandhi (1982) and

Lemon Tree (2008); and documentary series such as

A Force More Powerful [

35].

6. Nonviolence and Sustainability

Nonviolence is an important element of sustainability for three main reasons. One is that nonviolent action has long been used by environmentalists, conservationists, and preservationists to protect environments from damage and to advocate for more sustainable societies, institutions, and processes. The following section details some case studies of effective Australian environmental campaigns, showing that, historically, nonviolence has played a major role in movements for sustainability and will potentially be more important than ever as the Earth reaches climate and biodiversity tipping points at the same time as entrenched vested interests continue with a ‘business-as-usual’ attitude. For example, the day before school students and supporters held a May 2021 national strike for climate action, the Australian government announced it would spend

$600 million on a new gas-fired energy plant [

36].

Secondly, this environmental action has often included resistance to capitalism, consumerism, the infinite growth paradigm, and most pertinently for this article, militarism. That is, nonviolent action has opposed militarism as a whole and as a paradigm, as well as opposing particular aspects of militarism, such as United States military bases in Hawai’i [

37], the entry of nuclear-armed warships into New Zealand’s harbours, or the global opposition to the invasion of Iraq in 2003 by the ‘Coalition of the Willing’, one of the largest single weekends of protest the world has ever witnessed [

38]. This anti-military activism has usually been for a range of reasons and motivations, one of which is concern about the environmental footprint of militarism. Others include moral opposition to killing, especially of children, the elderly, women, and non-combatants in general, as well as concerns about the costs of militarism, concerns about the economic and trade impacts of war, arms races, secrecy and hierarchy of militarism, toxic masculinity, links to gendered violence, the corruption of the arms trade, and links to gun violence and civilian massacres [

39].

The third reason why nonviolence is important for sustainability is because it offers an alternative to militarism as a means of national and regional self-defence and the removal of dictatorships, genocidal regimes, and military juntas (such as Myanmar’s). The latter may be necessary under the ‘responsibility to protect’ doctrine developed in recent decades in the aftermath of genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda, and elsewhere, that the requirement for the international community to protect civilians and minorities sometimes overrides notions of national sovereignty [

40]. Following the discussion of Australian nonviolent environmental campaigns intended to enhance sustainability, I will show why nonviolent anti-militarism actions are so important for environmental sustainability through an exploration of the environmental costs of militarism and war, and therefore the urgent need for alternative methods of conflict transformation.

7. The Franklin River Campaign

In 1976, the Tasmanian Wilderness Society (TWS) formed to oppose the Gordon-below-Franklin hydroelectric scheme and its plan to inundate one of the world’s few remaining temperate wilderness areas [

41]. Its campaign involved nonviolent action and civil disobedience on a scale never previously experienced in Australia, being the ‘first organised mass blockade in Australia’ [

42], and one of the world’s largest, most successful nonviolent actions until then [

43]—which resulted in the preservation of almost 800,000 hectares of ‘wilderness’ in the southwest of the island state of Tasmania. The campaign was remarkable for its participatory-democratic nature and the significant involvement of women in leadership roles [

44]. It involved a record-breaking informal vote in a referendum and ‘one of the largest per capita rallies ever held in Australia’ [

45].

Politically, the campaign aided the election to federal parliament of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) [

46] where it remained for thirteen years (unprecedented before or since for the ALP) after decades of mainly conservative governments. The ALP government stopped the dam and successfully defeated a High Court challenge by Tasmania, resulting in major legal ramifications [

47]. The decision generated a more centralised Australian federation and re-interpreted the conventional demarcation of responsibility for environmental matters under the Constitution, thereby allowing the federal government to preserve wilderness areas of international significance and leading to a national system of reserves under Commonwealth control, with additional international support through World Heritage agreements.

For many participants, including this author, the Franklin campaign was a profound and life-changing experience involving emancipatory learning in social and deep ecology, experiences of a sense of belonging and creativity rarely felt before, and the forging of deep connections with the wilderness and fellow activists [

48]. They also learned skills that would prove useful in other campaigns, such as facilitating meetings, public speaking, movement organising, operating radios, and repairing boats and operating them in fraught circumstances [

49]. The success of the blockade convinced many of the blockaders of the efficacy of nonviolent direct action. The Franklin success empowered activists, gave them hope, and showed that their actions were worthwhile.

8. Anti-Uranium Blockades

8.1. Roxby Downs

Inspired and buoyed by the successful Franklin campaign, environmentalists collaborated with Kokatha Aboriginal traditional owners, peace activists, and students in a 1983 blockade of the uranium mine at Roxby Downs in South Australia’s remote desert region. They held concerns about uranium fuelling the nuclear weapons cycle globally—either directly or by adding to stockpiles that were vulnerable to terrorist attacks. There were also concerns over the mining itself, which impacted sacred sites, released carcinogenic radon gas, and massively depleted the Great Artesian Basin on which both ecosystems and farmers in three states rely. Nuclear power was said to be unsafe, centralised, secretive, and posed security risks, and the requisite long-term disposal of radioactive waste was still unresolved [

50]. Although the nuclear industry is now promoting nuclear energy as a way of mitigating climate change, these concerns remain valid for many people, and the extensive time, economic costs, and carbon-intensive resources, such as cement, needed for the construction of nuclear stations make it a poor solution, as does the industry’s extreme vulnerability to climate change [

51].

In August 1984, another blockade occurred after comprehensive nonviolence workshops occurred to ensure more disciplined and effective action. These included role-plays, discussions of nonviolence theory and history, and practice in making decisions through the ‘consensus’ method utilised by the Quaker-influenced anti-nuclear Clamshell Alliance in the USA. It was felt that stronger, clearer nonviolent practices had to be instituted and small ‘affinity groups’ formed prior to the action in order to better cope with the fraught, volatile environment predicted for Roxby II, which was opposing both the state and a wealthy corporation. A larger and more diverse contingent was involved with many more professionals and university students.

Despite a massive securitisation of the mine and battalions of police and security guards, several groups (including this author’s affinity group from the University of Sydney) were able to reach the mine and slow down work. Mass arrests and (almost inevitably) guilty findings at ‘kangaroo courts’ followed [

52]. Nevertheless, creative actions persisted, such as a group of women plugging a mineshaft with a three-metre tampon emblazoned with messages such as ‘Womyn know about hidden blood—plug the shaft—stop the cycle’. This was one of numerous effective actions by women who were determined to have a strong, assertive presence. Christians performed a church service in front of one of the mine gates with police initially being reluctant to end it. Another action was a group of doctors attempting to visit and distribute pamphlets at the nearby mining town to explain the dangers that the workers and their families faced.

Despite the improved commitment to nonviolence training that led to less violence at the second Roxby blockade, the inevitable tensions that characterise any challenges to the status quo persisted. The actions, arrests, and incarcerations were traumatic for many, and the failure to stop the mine was dispiriting. However, the blockades instigated the first close contact with Aboriginal people for many activists, and many obtained a closer understanding of the culture, strengths, oppression, and challenges of the Kokatha people. In this way, the eco-pax movement shifted towards becoming more holistic and inclusive, with significantly improved interaction with and respect for Aboriginal owners than the mainly tokenistic interactions at the Franklin action [

53].

The next major anti-nuclear and pro-peace actions were bike rides. One was The Bike Ride, a large, fairly unwieldy group riding from Adelaide to Alice Springs in 1986 despite few resources, support vehicles, or communications capabilities. The group held protest rallies at Roxby Downs and military facilities in SA and the Northern Territory (NT) and visited remote Aboriginal communities, such as Nepabunna, to build movement solidarity. In 1998 a smaller group, the Cycle Against the Nuclear Cycle (CANC), successfully completed a 4000-km epic from Melbourne to Jabiluka in the remote Northern Territory (NT) with favourable (though small scale) media. CANC was more focused on befriending and educating people in the communities they passed through than on high-profile protests. They networked with Aboriginal people at every stage and produced quality videos that were played nationally on a government broadcaster. Music, firestick twirling, monocycle riding, and juggling were frequently used as artforms designed to find common ground with onlookers, dissolve barriers, and entertain [

54].

These rides demonstrated that a small, well-organised, cohesive group could be more effective than a mass event with few resources and strained group dynamics. Similar actions, such as various ‘Peace Buses’ that toured Australia, received little media attention but demonstrated ongoing resistance to militarism and nuclear power. They contributed to the development and evolution of the eco-pax protest culture and movement [

44,

54], and likely contributed to the success of the 1998 ride and campaign at Jabiluka.

8.2. Jabiluka: A Blockade Led by Aboriginal People

One aim of CANC was to draw attention to the blockade of a uranium mine proposed for Jabiluka. This campaign had been organised by the Mirrar traditional owners in league with student and environmental organisations. In a sign of the evolution of the eco-pax movement, most of the external activists showed respect for the Mirrar and acceptance of Mirrar sovereignty over the site and the campaign. Tactical advances included more emphasis on boycotts, divestments, and sanctions, led by The Wilderness Society and the Mineral Policy Institute quietly lobbying businesses to divest from the Energy Resources of Australia project. This was supported by Jabiluka Action Groups engaging in colourful occupations and protests outside businesses and banks that were funding the mine. The result was the withdrawal of large amounts of money, amounting to almost seven million dollars, from the mine’s backers [

55]. This widespread and diverse campaign demonstrates how different types of groups can complement each other, cover different ground, and achieve an overall objective.

This author observed that interactions with police were also better than at Roxby for the most part, and some police were sympathetic towards and supportive of the protests and less inclined to act officiously or arbitrarily. The movement showed greater maturity, discipline, group dynamics, and commitment to nonviolence. This disciplined civil disobedience remained effective and put immense pressure on the government infrastructure, such as its jails, police stations, and courts. Activist Anthony Kelly, working in a police liaison role, was contacted by police while in his jail cell and begged to halt rallies—temporarily or permanently—because police were unable to deal with the overload of people in custody. Meanwhile, the blockade and boycott campaign were having a serious impact on the mining corporation, leading them to intimidate protesters and successfully pressure the police to escalate to more serious charges against the protesters [

56]. Finally, however, the campaign and its global publicity forced the corporation to engage in a legal agreement with the Mirrar people that Jabiluka would not be developed without their consent [

57], which they continue to refrain from giving.

9. Forest Blockades

In the late 1980s, the North-East Forest Alliance (NEFA) formed in northern NSW. Their actions built upon those of an earlier generation of activists in the region who had revolutionised political action in Australia through the use of nonviolent direct action to stop rainforest logging at Terania Creek, Mt. Nardi, and Nightcap [

58]. Those actions had influenced the TWS decision to use nonviolent direct action at the Franklin, albeit in a more orthodox, centrally-controlled form, but this form of nonviolence led to a reaction towards militancy at Roxby Downs. That trend towards militancy continued at a rainforest blockade at Daintree in far north Queensland and during the NEFA blockades, with important tactical developments occurring concurrently in forest action throughout Australia, in NSW at the Southeast Forest Alliance (SEFA) blockades at Tantawangalo and Coolungubra, in East Gippsland (Victoria), in southwestern Western Australia, and in Tasmania’s Tarkine region [

23].

The reasons for campaigning for ‘old-growth’—i.e., ecologically-mature forest that has had minimal human disturbance—are numerous and varied and range from rigorously scientific to purely aesthetic. They have been well-documented elsewhere (e.g., [

59,

60], so they are only briefly mentioned here. Although each blockade had slightly different issues, most shared common rationales, such as to slow the current unprecedented crisis of extinction of species—partly because ‘the planet’s forests are being irrevocably lost in what amounts to a mere tick of the geological clock’ [

59]. Over half of Australia’s land animals and three-quarters of its plants live in forests and woodlands, yet protected forests that have never been logged cover just 0.3% of Australia’s land area [

60]. Australia already has a high rate of extinctions, with logging further threatening biodiversity. Burning, poisoning, and roading that accompanies logging has a disastrous effect on many species and makes the forests more fire prone [

61]. Also, the logging was not for essential building or value-added products: ‘over 90% of old growth logs taken from public land are turned into woodchips and exported’ [

62]. There was often little financial gain to the community from logging (and export woodchipping particularly), with the taxpayer often subsidising large corporations. Job losses, while blamed on conservationists, were inevitable through new technology, company ‘rationalisations’, and the limited nature of the ‘resource’ [

63]. In the vast majority of situations, the value of forests for tourism, recreation, and sustainable employment was much greater than for logging.

Conservationists argued that the forests had an intrinsic right to exist, independent of humanity, but there were anthropocentric reasons too for old-growth preservation:

Healthy old growth forests are regarded as integral to the long-term and consistent supply of high-quality potable water to urban centres, as well as to supply farms and support aquatic ecosystems. Water is stored by and slowly released by old-growth forests and is underappreciated for its high economic, ecological, and social value [

60].

NEFA began as a small, informal network of alternate life-stylers who had moved ‘back to the land’ to build self-sufficient communities of progressive like-minded souls. Having built their own houses on forested land near Kyogle, they were well-resourced with building equipment, tools, and 4WD trucks. Not expecting any assistance from mainstream environmental organisations, they began to create their own militant tactics in the forests of Chaelundi, while also utilising more orthodox tactics such as lobbying, taking action in the law courts of NSW, and establishing protocols with the police. Assisted by riggers who had worked on film sets, they established a range of physical impediments to entry by loggers and police—for example, by building tripods that activists could climb and burying large concrete pipes that they could occupy. Some activists chained themselves to bulldozers [

64]. Others were partly buried in holes, and some even had derelict cars placed over them, to which they locked themselves in. Fires, heated rocks, and other obstacles found in the forest were all employed to further delay the entry of loggers. Despite a considerable police presence, this militant form of action enabled a significant and empowering victory for NEFA; it both impeded logging and gained media attention and was complemented by successful court action [

65].

Similar blockades occurred at Mt. Killiekrankie, which was the beginning of a year of constant blockading throughout 1992. Other sites included Mummel Gulf, Wild Cattle Creek, Styx River, Carrai, Toonumbah, Wollumbin, and Mistake State Forest. The activists, including this author, survived on minimal income with few resources in the rugged mountainous wilderness of Australia’s Great Dividing Range—where nights often had sub-zero temperatures [

66]. With drinking water limited, health issues emerged, and with the camps open to all, group dynamics were often stressful—on top of the harassment, surveillance, and occasional violence by loggers and authorities. Some organisational aspects, however, were highly professional, such as the communication networks and communal kitchens. The blockades had a tribal feel and were aided by engagement with Aboriginal activists and donations of supplies from sympathisers.

The use of innovative devices to physically delay logging was obviously effective, with more than a million hectares of forests preserved and a doubling of the area’s national park estate [

67]. Political consequences included the resignation of the NSW Education Minister, and later that of the state Premier, and important new endangered species legislation [

68]. NEFA activists such as Aidan Ricketts were also engaged by other activist organisations to teach their new skills and expertise, with long-term consequences—as we shall see below. The successes also inspired an eco-pax movement that had slumbered somewhat under a federal Labor government and enjoyed few grassroots or major victories. Locally, it positively influenced the region’s cultural, political, and social life, thereby enabling skills education, community development, empowerment, and a sense of purpose for long-term unemployed people [

67]. As Boughton and this author have noted elsewhere, such community actions are often high-pressure educational environments where learning and teaching are fast-tracked, and occur in an interactive, egalitarian—rather than didactic—hierarchical manner. It usually occurs in a continuous, informal and non-formal process, as opposed to formal or institutional education, and it happens on three levels: instrumental, communicative (or interpretive), and emancipatory (or critical) education. The former two can aid with future careers, while the latter can result in fundamental change to people’s worldviews and life paths [

49,

69]. Despite its effectiveness, education in nonviolent movements has been accorded little academic research (with exceptions such as [

70]).

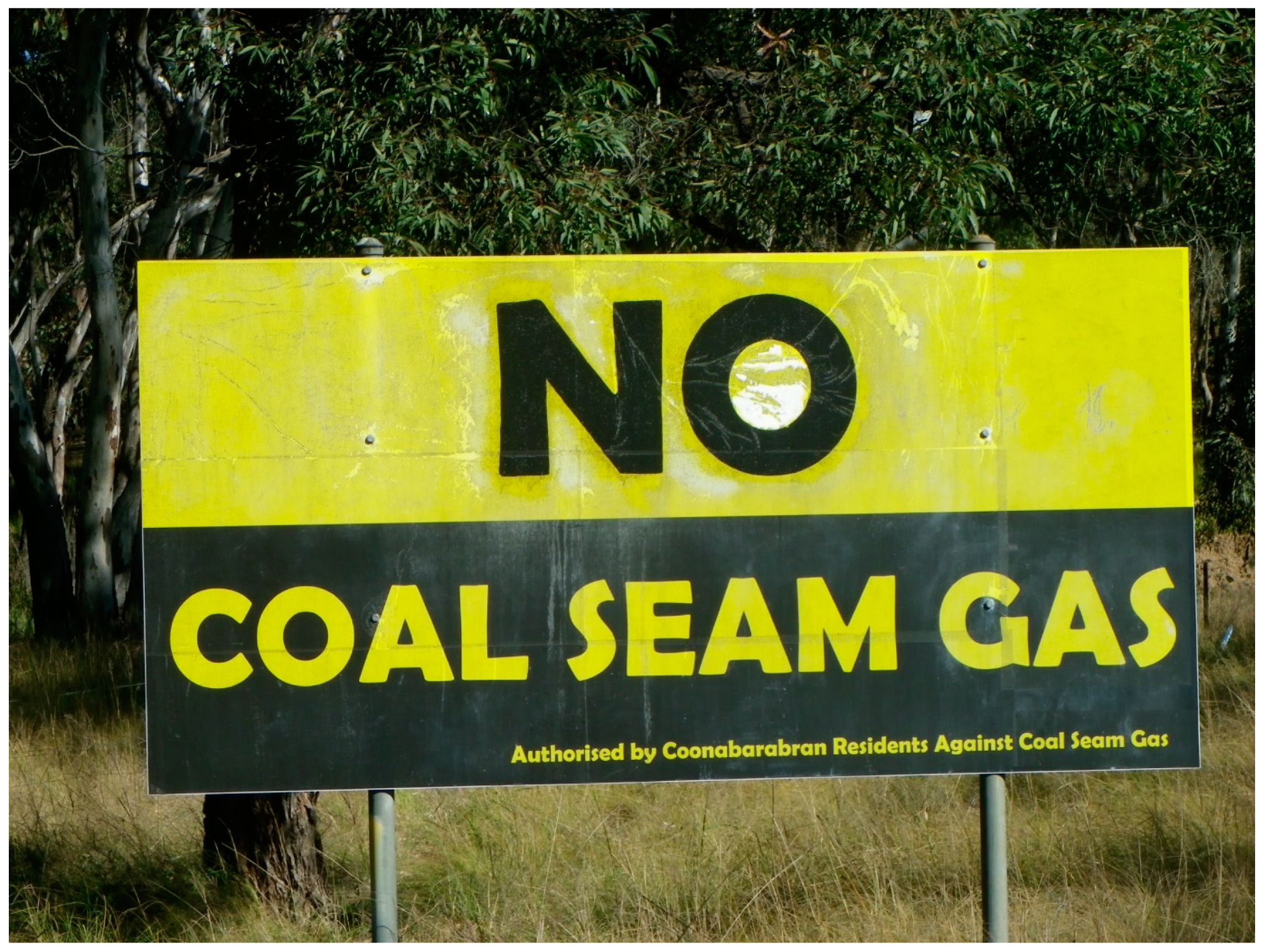

Bentley and Beyond

Building on the success stories and movement building of the Nightcap, Franklin, NEFA and Jabiluka campaigns, the Bentley campaign (2010–2014) against coal seam gas (CSG) extraction used intentional targeting of the media with theatrical, colourful, and musical actions, as well as clever framing. New developments included the use of social media and online platforms such as YouTube, with videos challenging stereotypes by framing activists as ‘protectors’ rather than ‘protesters’. Activist and law academic Aidan Ricketts describes Bentley as part of the fastest growing movement in Australian history, which was composed of an unprecedented coalescence of environmentalists, Aboriginal people, and farmers in loose coalitions of groups such as ‘Lock The Gate’, ‘Frontline Action Against Coal’, and ‘Gasfield Free Northern Rivers’, and were supported by more formal groups such as The Wilderness Society [

71,

72]. As with other campaigns, though it is under-reported, women played a major role as leaders, strategists, artists, and communicators [

44]. High profile supporters, for example, included Jenny Dowell, Mayor of Lismore, and Danielle Mulholland, Mayor of Kyogle, who occupied a tripod. Blockade spokesperson Elly Bird was later elected to Lismore Council to address ‘democracy deficits’, as was evident at Bentley, where CSG development was being forced on a population despite 87 percent opposing it [

72].

Bentley has been one of the most effective campaigns to date against CSG in Australia; it succeeded despite opposing a wealthy corporation, Metgasco, supported by a Coalition state government widely believed to be in the pocket of such corporations, and which was planning to send in 800 riot police to quell the rising tide of civil disobedience and non-cooperation [

73]. The suspension of Metgasco’s licence was widely regarded as a ‘historic moment’ that was as significant as the Franklin Dam win and the long community campaign that helped end Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War [

74].

Nonviolent protest cultures in Australia have continued to develop with improvements in organisational dynamics [

72], consensus decision-making, acceptance of Aboriginal leadership [

54] corporate campaigning [

75], artistic activism, ‘active resistance’ techniques, and information and communication technologies [

23]. Although climate campaigns against coal and CSG at Leard Forest and the Pilliga region (

Figure 2) are yet to succeed, the widespread, diverse, and effective resistance to gas extraction at James Price Point (Western Australia), Bentley, and elsewhere indicates that nonviolent direct action remains a powerful force. Forest blockades also continue to be effective, such as 2021’s Camp Nunguu near Urunga in NSW (

Figure 3).

The elements of drama, music, colour, humour, and play that the Franklin River blockades’ artistic activism popularised, moving protest from the activities of the committed few to mass civil disobedience [

76], have since been a strong factor in the growth of other mass campaigns, such as the School Strikes for Climate, with their clever, humorous signs, and the Extinction Rebellion protests, with their dramatic ‘Red Rebels’ theatrical performances. This dynamic is aided by a growing body of research into ‘eco-arts’—art forms used in the service of environmentalism—which, in Australia, revolve around Eco-Arts Australis’s conferences, projects, and publications (such as [

77]).

10. How These Nonviolent Actions Contributed to Environmental Sustainability

Without these environmental blockades and campaigns, the Franklin River’s forests would be drowned and emitting greenhouse gases through rotting vegetation [

78]. The valuable carbon sinks in the Chaelundi and other old growth forests would have been lost. The water and land at Jabiluka (and then overseas) would have been polluted for many generations by radioactive substances, thereby impacting inter-generational equity. The intimate, long-term relationship between Aboriginal people and the environment at Jabiluka, Bentley, and James Price Point would have been severely disrupted, in addition to the environmental pollution and greenhouse gases released. Bentley’s underground water sources, on which farmers and ecosystems rely for sustainability, may have been irrevocably destroyed [

79]. Although often depicted as radical and extremist by their detractors, others see the eco-pax activists as ‘patriots’ defending their country from multinational corporate exploitation [

80].

As well as the obvious, immediate, visible, or direct impacts of these actions, there are more intangible ones that nevertheless also contribute to both environmental sustainability and positive peace in the long term by helping to build community capacity and develop movements and their knowledge and skillsets. They have empowered individuals and strengthened local communities and national networks and provided valuable job training in informal and non-formal settings, as well as facilitated leadership opportunities [

49,

67,

68]. These findings complement Simangan et al.’s argument that environmental sustainability should be viewed as one of the pillars of positive peace [

9].

Such determined nonviolence succeeded when political and institutional processes did not. Nonviolence has been an essential element of sustainability in those communities and, more widely, has been most effective when nonviolence training has occurred when using experienced trainers and activists, as well as when nonviolent discipline has been established at a strategic level across the entire campaign.

Having examined a number of influential Australian case studies of nonviolent action as the action research component of this paper, we will return to nonviolence later in a wider, international context, in relation to sustainability. However, first let us examine, on the other hand, the use of violent, militaristic methods and explore their environmental and economic costs.

11. Militarism and the Military-Industrial-Media-Entertainment-Finance Complex

In my monograph

Global Warming, Militarism and Nonviolence: The Art of Active Resistance [

23], I drew on Vivienne Jabri’s

Discourses on Violence [

81], David Campbell’s

Writing Security [

82] and the work of David Apter to define the pervasive phenomenon of militarism as a set of pervasive hegemonic discourses, power structures (which are often covert), and everyday practices (often unconscious) that direct individuals and societies towards large-scale violence. This is not just obvious physical violence but may include ‘cultural violence’, which supports direct violence by dehumanising or vilifying the ‘enemy’. Militarism may also support and encourage ‘structural violence’—such as inequitable economic systems where people die from hunger, poverty, or ill-health despite the presence of adequate resources nearby. Another form of violence of particular importance to this paper is ‘ecological violence’, where ecosystems are unnecessarily damaged, such as through warfare [

3].

The physical manifestation of militarism is the military-industrial-media-entertainment-finance complex (MIMEFC) see [

83,

84], which includes the world’s military forces as well as all the industries that supply and support them. This behemoth includes many multinational industries with a heavy environmental footprint, such as fossil fuels, automobiles, aviation, and nuclear power [

85], with examples being such respectable household names as Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and General Electric. It operates in lockstep with the state [

86] in a ‘permanent war economy’, as depicted by George Orwell in his 1948 novel

1984, and it has a vested interest in the continuation of militarism and war.

As the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute notes, arms production and procurement deals are worth hundreds of billions of dollars a year. Aiding the might and covert strategies of the complex is an unofficial ‘revolving door’ policy in which former senior government figures are appointed to its executive boards and vice-versa. The complex’s connections, wealth, and lobbying power, such as spending

$101,907,368 in one year alone to lobby the United States government [

87], enable it to control and profit from both the development and manufacture of arms, armed conflict, and the post-war reconstruction of conflict zones. To illustrate how this power warps governmental expenditure priorities, the United States allocates approximately 58 percent of its discretionary spending towards its militaries, whereas it only dedicates 4 percent to supporting education [

88].

12. The Impact of War and Militarism on the Environment

My monograph also detailed the enormous environmental pollution and resource depletion occasioned by war, militarism, and the complex (summarised in

Table 1). It examined the insatiable energy demands of militarism, how militaries operate in secrecy, and are usually exempted from climate action and accountability (see also [

89]) as well as how tax revenues could be used to address the emerging environmental catastrophe instead of continuing to be siphoned by the powerful corporate forces behind militarism [

23]. Below I summarise the main environmental impacts of war and militarism.

From the earliest days of humanity, warfare has impacted environments, such as European deforestation from building warships and fortresses [

90]. More recent manifestation have been the destruction of Vietnamese rainforests by Agent Orange herbicides [

91] and chemical spillages caused by violent attacks or human error that have caused widespread damage to soil and negatively affected agriculture [

92]. The extraction of rare minerals for military technologies generally occurs in conflict-wracked and poverty-stricken countries in an unethical manner, resulting in structural and ecological violence [

93]. Land mines abandoned after conflicts disproportionately kill or injure children, farmers, and animals in poor, rural regions of the third world [

94].

Oil spills and destroyed pipelines have damaged ocean ecosystems [

95] as have discarded munitions and chemical weapons [

96]. Battleships and tankers sunk during conflicts or by accident continue to impact aquatic food chains [

97], while the low-frequency sonars used by naval vessels are harmful to cetaceans, such as beaked whales [

92].

Hazardous waste impacts both land and sea [

98], including the manufacture and disposal of nuclear weapons [

91,

99], while the testing of nuclear weapons, such as at Muroroa Atoll, has affected land, sea, and sky and left long-lasting health problems for Pacific and other communities [

91]. Atmospheric testing was only halted through a determined international campaign.

Military aircraft are major contributors to global warming and air pollution [

100,

101] while the atmospheric release of chlorofluorocarbons has resulted in the depletion of the ozone layer [

91] that, again, has only gradually been improved of late through concerted international action. Most military activity outside of major crises consists of training exercises [

92], thereby creating health impacts—such as elevated rates of cancer—near bombing ranges [

102].

All the above-mentioned impacts have a direct or indirect effect on the climate, with emissions from military vehicle production and use, burning oil wells, deforestation, crop destruction, construction and supply of military bases, extraction and transport of fossil fuels, and post-conflict reconstruction of countries (often by military-linked corporations) all releasing masses of carbon into the atmosphere and making a major contribution to global warming [

103]. Although Chinese, Russian, Korean (North and South), and other nations’ militarism is alarming, the United States is responsible for almost half of the globe’s spending [

104]—or three quarters if you include their allies [

105]. This expenditure translates into highly significant military pollution and resource depletion, with the US military being the single largest institutional polluter on the planet [

106,

107].

The wealth, power, and influence of MIMEFC are such that its carbon footprint is rarely taken into account at international forums when measuring a country’s environmental obligations [

89]. Defence forces are regarded as essential and above scrutiny, rather than subject to measurement and accountability as are all the other aspects of societies, even though the provision of water, food, housing, healthcare, and education are all more essential on a daily basis. Such measuring that occurs may only examine limited aspects of ‘defence’ rather than all the MIMEFC footprints that contribute, such as in the internationalised production of aircraft carriers. Yet these footprints are all taxpayer-funded, and the public should have the power to reduce them. It is government patronage—not human nature or inevitable forces—that underwrites and guarantees the continuance of dinosaur industries, outdated technologies, and outmoded methods of conflict resolution.

This section has summarised some of the many ways in which widespread and long-lasting environmental pollution and resource depletion are occasioned by war, militarism, and the complex that supplies and supports them. Globally, environmental sustainability is severely compromised by them. It is clear that if the world is to progress to a more sustainable place that is able to survive, adapt to, and hopefully mitigate the global warming and biodiversity crises, militarism needs to be confronted and minimised—despite the enormity of this challenge. This section supports the contention by Simangan et al. that negative peace (or the absence of war) is one of the dimensions of sustainability [

9].

13. Nonviolent Defence and Nonviolent Regime Change

As suggested above, a rapid reduction in war and militarism is an essential element of sustainability. One method of achieving this is through a greater understanding of, resourcing of, and reliance upon nonviolent methods of national defence and removal of genocidal regimes. As mentioned in the nonviolence introduction section above, nonviolent methods have been instrumental in the removal of numerous regimes as well as in some examples of national defence, such as Denmark’s resistance of its WWII occupation by Nazi Germany [

108]. Successful anti-colonial campaigns, such as India’s independence movement, could also be regarded as examples of effective nonviolent national defence against foreign occupation.

Other examples include the overthrow by civic strikes of nine dictatorships in South America between 1931 and 1961 [

26], followed by the 1988 removal of Chile’s dictator Augusto Pinochet. In 1986, a nonviolent movement over thirty months, assisted by a rebellion by military personnel, succeeded in deposing the ruthless Philippines dictator Ferdinand Marcos, something which armed communist guerrillas failed to achieve over seventeen years. Examples elsewhere in the world include the deposing of the Shah of Iran in 1979, the dismantling of the Iron Curtain in the early 1990s [

21], and the overthrow of Slobodan Milosevic in 2000 and Hosni Mubarak in 2011—entirely or mainly through unarmed popular resistance. If nonviolence can succeed against even the most ruthless of dictators and totalitarian police states, could it not be developed more widely as a means of national defence and for international forces to use to uphold their Responsibility to Protect obligations?

A number of theorists have utilised such examples to envisage a much more widespread use of nonviolence for national defence, such as Desmond Ball in his pioneering

Strategy and Defence [

109], Gene Sharp’s

Making Europe Ungovernable: The Potential of Civilian-based Deterrence and Defence [

110] and his later

Civilian-Based Defense: A Post-Military Weapons System [

111]. More recently, Jorgen Johansen and Brian Martin released

Social Defence [

12], which gives a detailed proposition for nonviolent defence as a viable alternative (see also [

23]). Despite this work, the concept of nonviolent defence has achieved little traction and could be better theorised and more widely promoted, such as through peace education. Academies, similar to military ones, could be employed to train both leadership teams as well as large numbers of citizens for widespread popular resistance. There are kernels of such peace education in the various Peace Studies departments at universities around the world, such as in Armidale, Australia and Bradford, UK, or in the UN-mandated University for Peace in Costa Rica. These are struggling under the neo-liberalisation and commercialisation of universities; they usually lack corporate sponsors, and their financial benefits are not immediately obvious. However, the dividends of peace are enormous, including the environmental, social, and economic factors, as demonstrated initially by political economist and Peace Studies pioneer Kenneth Boulding [

112], and more recently by the

Positive Peace Report compiled by the Institute for Economics and Peace [

113].

14. Results

The case studies component of this paper, which is reliant on an emic action research methodology, described a number of pivotal Australian nonviolent environmental campaigns that showed how bold, strategic, and creative actions can protect environments, resist ecological damage and depletion, and contribute to sustainability in numerous ways, including acting for social justice and positive relationships as well as environmental sustainability. These case studies demonstrated the effectiveness and potential of nonviolent action; its educative and empowerment qualities for activists, movements, and communities; and its ability to evolve according to need. The Australian environmental case studies also showed, albeit on a minor scale in a wealthy democracy, how nonviolence can be useful for the defence of a community from outside aggression, such as in the successful Bentley resistance. Here, an entire community in the Northern Rivers region of NSW, despite negligible institutional or corporate resourcing, used a wide range of nonviolent tactics, including lobbying, artistic activism, civil disobedience, and widespread non-cooperation, despite—or perhaps because of—the threat of 800 riot police being sent into the community from cities such as Sydney. Engagement in such actions is like joining an informal academy—informal, yet educationally effective as the learning occurs during actions in the real world. These campaigns demonstrate some of the immense potential of nonviolent defence. Nonviolence does not always succeed, of course, but nor does military violence, no matter how well-resourced—as demonstrated by the failure of the USA, the most-well-armed nation in human history, to subdue the communist aspirations of the poverty-stricken Vietnamese or to eradicate the Taliban from Afghanistan.

The review aspect of the paper exposed the enormous environmental footprint of war and militarism; described the wealth, power, and influence of the military-industrial complex; and showed how this has prevented any concerted international effort to examine and reduce its carbon footprint. This is, therefore, a major shortcoming in global moves towards environmental sustainability, which requires addressing with creative solutions as reducing this footprint is an essential component of global sustainability. This review section also described some of the little-known history of successful nonviolent action throughout the last century and across the world, even against the most ruthless of opponents. Again, this suggests that there is a nascent potential for nonviolent action to become more prominent as an alternative method to armed violence for transforming conflicts.

15. Discussion: A Blueprint for Action and Change

Anti-war movements also contain the kernels of much larger and stronger nonviolent forces. Following the successful Australian resistance of the 1991 AIDEX armaments fair [

114], the Melbourne-based International Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) became a global movement that succeeded in creating the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which made nuclear weapons illegal under international law from 22 January 2021. This is a legally-binding global agreement that prohibits signatory states from ‘developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, stockpiling, stationing, transferring, and using or threatening to use nuclear arms’ or to assist or encourage the prohibited activities [

115]. This nonviolent movement could be regarded as the global community defending itself against the threat (environmental and social) of nuclear war.

In 1931, peace campaigner and suffragist Maude Royden became an early advocate for a ‘Peace Army’, which would be composed of unarmed activists who would use nonviolent methods to intervene in and defuse armed conflicts. The

Shanti Shena and

Khudai Khidmatgar peace armies of India were practical examples of this in the following decades [

116]. The 1990s saw a resurgence of the practice with the ‘Gulf War Peace Camp’ and the ‘Time for Peace’ rally in 1990, followed by the ‘Walk for a Peaceful Future in the Middle East’ in June 1992 [

117]. In the second Palestinian

intifada, there were human shields and concerted advocacy across borders [

118], and the Balkan Peace Team operated in Serbia, Croatia, and Kosovo from 1994 to 2001. Perhaps the best known, most enduring, and effective organisation has been Peace Brigades International, wherein small groups accompany dissidents or activists in authoritarian regimes and use their profiles and connections in order to protect them and demonstrate international solidarity for human rights [

119]. Nonviolent Peaceforce is an emerging Brussels-based non-governmental organisation that has worked in conflict situations in Guatemala, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka. Other proactive nonviolent organisations include the World Peace Brigade, Witness for Peace, and Christian Peacemaker Teams [

120].

Such organisations could be the core of mass people’s movements to repel and resist invasions and military coups, both at home and abroad. Using coordinated stratagems of defending sovereignty nonviolently, they could lead to widespread non-cooperation, defiance, disruption, assertive resistance by people and institutions, and attempts to subvert and convert the invader’s forces [

109]. Well-prepared civilian-based defence could deny or frustrate the invader’s aims and make any long-term occupation difficult or impossible, particularly if the international community supported the resisters through sanctions, boycotts, and diplomatic pressure on the invading power, which would further undermine the invader’s pillars of support. With the extraordinary advances in communications technologies in recent decades, the world is more connected as a global village than it ever has been with the availability of instantaneous mass communication making it possible to mobilize support quickly.

Leading nonviolence theorists such as Sharp [

110,

111], Watner [

121], and Johansen and Martin [

12] have examined such scenarios in detail, providing useful blueprints for action. They advocate measures ranging from the broad, such as the decentralisation of economics, politics, and society [

122], to the minute, such as removing or changing street signs. Some suggestions are at the fringe of nonviolence, such as destroying infrastructure, highways, tunnels, bridges, communications equipment, and arms. While some would regard such acts as not nonviolent (e.g., [

123]), others regard them as legitimate in some circumstances and occasionally necessary (e.g., [

124,

125,

126]).

Less destructive sabotage could include factories and essential infrastructure being engineered such that they can be rendered inoperable at short notice through the removal of essential parts [

127]. Industries, systems, and essential utilities such as water, power, sewage, and garbage disposal could be disrupted by targeted or general strikes [

12]. Labour forces could be decimated by stay-at-home strikes or protest emigration. Aggressor attempts to control and utilise existing administrations and bureaucracy could be thwarted by boycotts, go-slows, and deliberate incompetency by officials, bureaucrats, and public servants. Processes could be established to ensure that communications and media systems continued to function underground in the event of an invasion. Dispersed acts of dissent and protest, such as temporary, mobile ‘flash mobs’ could demonstrate opposition and erode aggressor morale and legitimacy while inspiring the population to resistance [

128]. Mass rallies of opposition and vibrant, creative musical blockades could occur if safe—preferably using well-trained and experienced nonviolent activists and organisations [

129].

While reliance on nonviolent rather than violent defence may seem naïve against violent opponents, the former surprisingly has a ‘greater track record of success than violence’ and is a ‘crucial ingredient for any society to move toward positive peace’ [

8,

130]. Lithuania, which nonviolently resisted Russian military force from 1955–1991—when it gained its independence [

131]—strongly emphasises the role of civilian resistance (albeit both armed and unarmed) in the defence of the state, an approach incorporated into Lithuania’s 1992 National Security Concept, which has endured since [

132].

Creating a society prepared for determined nonviolent resistance would involve costs, challenges, and changes, but would have a much lower environmental footprint and lower economic costs than maintaining standing armies, navies, and air forces and engaging in armed warfare. Nonviolent defence could therefore cut defence spending dramatically. This would allow that money to be spent instead on environmental protection and sustainability programmes. Costa Rica, for example, dismantled its army and discontinued armed national defence in 1948; now it is globally recognised for its ‘democratic institutions, the remarkably healthy and happy population, and, not least, the fact that Costa Rica has been able to invest not only in its people but also in preserving about 25% of its land area in either national parks or biological reserves’ [

133].

The money saved from cutting ‘defence’ spending could also be used instead for education, health, the arts, poverty reduction, and homelessness—thereby reducing inequality and crime with further savings from fewer prisons needed, and healthier, better educated societies. More spent on diplomacy, aid, trade, and cultural exchange would reduce regional tensions, build links, and reduce regional arms build-ups. All this would contribute to social sustainability, which feeds into environmental sustainability; where people are less desperate and more educated, they tend to care for their environments better [

134]. All these societal and environmental improvements occasioned through a move from violent to nonviolent methods of conflict transformation would contribute greatly to positive peace.

16. Conclusions

This article has explored the connections between nonviolence and sustainability, arguing that nonviolence is an essential element of environmental sustainability and the cultivation of peace—two key concepts of the United Nations’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. While agreeing with Sharifi and Simangan [

1] that environmental sustainability should be added as an important positive peace indicator, the paper has argued that nonviolence should also be recognized as essential for environmental sustainability and positive peace. This accords with the Quadrant of Positive Peace proposed by Standish et al. [

135], which envisages positive peace to emerge from four aspirational and operational domains of peace, which include nonviolence, social justice, environmental sustainability, and positive relationships. Their platform is one of ‘engagement, action, and change: an interconnected appreciation that building peace in one part of the Positive Peace Quadrant is not enough’ [

135]. For them, nonviolence is an essential strategy of conflict transformation and ‘a foundational pillar of positive peace’ acting in personal, interpersonal, social, and international dimensions [

135].

The paper has described a number of pivotal Australian nonviolent environmental campaigns, showing how dedicated, strategic, and creative actions can preserve ecosystems, resist environmental damage, and contribute to sustainability in manifold ways—including acting for social justice and positive relationships as well as environmental sustainability. These case studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of nonviolent action; its ability to empower and educate activists, movements, and communities; and its ability to evolve according to need.

Those movements can also be viewed as seedbanks, which suggest the potential for stronger, better-resourced, and better-educated nonviolent movements. Although conditions and contexts in other countries may be quite different, the adoption of Australian tactics overseas [

23], such as active resistance ones [

136], and the importation of foreign tactics, such as the Freedom Rides initiated in the United States and replicated in Australia in 1965 [

28], indicate that successful movements have international influences.

The article also examined the environmental footprint of militarism and showed that reducing this footprint is essential for global sustainability. This footprint can be reduced by making militaries more environmentally-friendly, but a more fundamental long-term solution is to reduce militarism and the need for it by replacing it with nonviolent methods of defence and regime removal. This paper described some of the little-known history of successful nonviolent action throughout the last century and across the world, even against the most ruthless of opponents. The removal of violent dictatorships and totalitarian regimes is a vital aspect of positive peace achieved through nonviolent means. Following the Australian case studies, these examples indicate some of the immense potential of nonviolent defence and provide blueprints for action.

Replacing the expensive and polluting culture of militarism, war, and violence with nonviolent methods of conflict resolution would have threefold benefits. First, it would support nonviolent campaigns for environmental protection, sustainability, and poverty reduction. Second, it would eliminate a significant contributor to the global environmental crisis of resource depletion, climate change, and biodiversity loss. Finally, it would allow the redistribution of funds from militarism to climate mitigation and adaption strategies, as well as poverty reduction.

As Sharifi and Simangan observe, peace can promote sustainability as well as vice-versa; a more equitable and sustainable world that minimises ecological and other interrelated forms of violence is likely to be a more peaceful and harmonious world [

1]. Amster [

137] also notes the many opportunities for peacebuilding and cooperation that arise from addressing environmental problems nonviolently at local levels and as a global community. It is a two-way process with mutual benefits for all. Both environmental sustainability and well-resourced nonviolent institutions and processes deserve recognition and support as pillars of positive peace.

Although a move from militarism to nonviolent defence may seem unlikely and even naïve, it ‘could happen suddenly, for example as a result of a crisis’ [

12], and there is no greater international crisis than global warming. Such a shift is completely in accordance with the 2030 Agenda’s acknowledgement of ‘the bold and transformative steps which are urgently needed to shift the world onto a sustainable and resilient path’ [

5]. All positive change begins with a clear vision of a better future.