Interrelations of Ancestral Textile Handicraft Weaving and Tangible Vernacular Karkhanehs (Workspaces) in the Historic Destination of Yazd, Iran

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Actor-Network Theory and Thing Power

3. Case Study: Tracing the Relationships of Textile-Weaving and Karkhaneh

3.1. Research Setting and Background

3.2. Research Methods

3.3. Research Findings

3.3.1. Living/Working Vernacular Architecture: The Home Domiciles

3.3.2. Social/Working Vernacular Architecture Transition: Karkhanehs and Kargahs Ateliers in the Local Neighborhood

3.3.3. Vernacular Industrial Architecture in the City: From Karkhaneh to Industrial Manufacturing

4. The Industrializing Karkhanehs and Touristic Alterations

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Historic City of Yazd; Iran Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts, and Tourism Organization (ICHHTO). 2017. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1544/documents/ (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Crawford, C.S. Actor-Network Theory. In Encyclopedia of Social Theory; Ritzer, G., Stepnisky, J.N., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gürsoy, İ.T. Slow Food Justice and Tourism: Tracing Karakılçık Bread in Seferihisar, Turkey. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things; Duke University Press: Durham, UK; London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8223-4619-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, C. Non-Human Agency, Radical Ontology and Tourism Realities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 858–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan Pour Farashah, M.; Aslani, E.; Khademzade, M. Strategic Planning of Cultural Tourism Development in Historic City of Yazd (Case Study: Fahadan Neighbourhood). Almatourism-J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2018, 9, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, H. Tourism Development and Residents’ Attitude: A Case Study of Yazd, Iran. Tourismos 2010, 5, 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, M. A Persian Stronghold of Zoroastrianism; Clarendon: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Foruzanmehr, A. Thermal Comfort in Hot Dry Climates: Traditional Dwellings in Iran; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rastegar, R.; Zarezadeh, Z.; Gretzel, U. World Heritage and Social Justice: Insights from the Inscription of Yazd, Iran. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evaluations of Nominations of Cultural and Mixed Properties; ICOMOS: Kracow, Poland, 2017.

- Mohajeri, N.; Gudmundsson, A. Analyzing the Variation in Street Patterns: Implications for Urban Planning. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2014, 31, 112–127. [Google Scholar]

- Naiemi, A.H. Residential Compounds: Earthen Architecture in the Central Desert of Iran. In Earthen Architecture in Muslim Cultures: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives; Pradines, S., Ed.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 203–232. ISBN 978-90-04-35633-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, M.S. Ceramic House Models from Medieval Persia: Domestic Architecture and Concealed Activities. Iran 2008, 46, 227–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan Pour Farashah, M.; Aslani, E. A Tourism-Oriented Conservation Plan for a Historic Neighborhood Based on Urban Design Qualities: The Case of Yazd in Iran. Konwersatorium Wiedzy O Mieście 2021, 6, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts. Available online: https://www.mcth.ir/english (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Yazd Cultural Heritage Handicrafts and Tourism Organization. Available online: http://portal.yazdcity.ir/ (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Munakata, K.K. Weaving the Traditions for the Future: Building a Sustainable Support Framework for Iranian Traditional Hand-Woven Textile Arts. In Proceedings of the ACAS2015, Kobe, Japan, 28–31 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yavari, H. Nassaji Sonnati Iran [Traditional Iranian Textile]; Islamic Development Organization: Tehran, Iran, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meller, S. Silk and Cotton: Textiles from the Central Asia That Was; Abrams: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.S.; Munakata, K.K. Fabrics and Looms in Present-day Iran [Teixits i telers a l’Iran actual: Més enllà de les catifes perses]. Datatèxtil 2015, 32, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori Bafqi, A.A. An Introduction to the Textile Industry of Yazd in the Safavid Era. Pažuheš-Nâme-Ye Târix-E Ejtemâ’i Va Eqtesâdi Socio Econ. Hist. Stud. 2013, 2, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ramazankhani, S. Honar-e Nassaji Shahr-e Yazd [The Art of Yazd Textile]; Nashr-e Sobhan: Yazd, Iran, 2008. [Google Scholar]

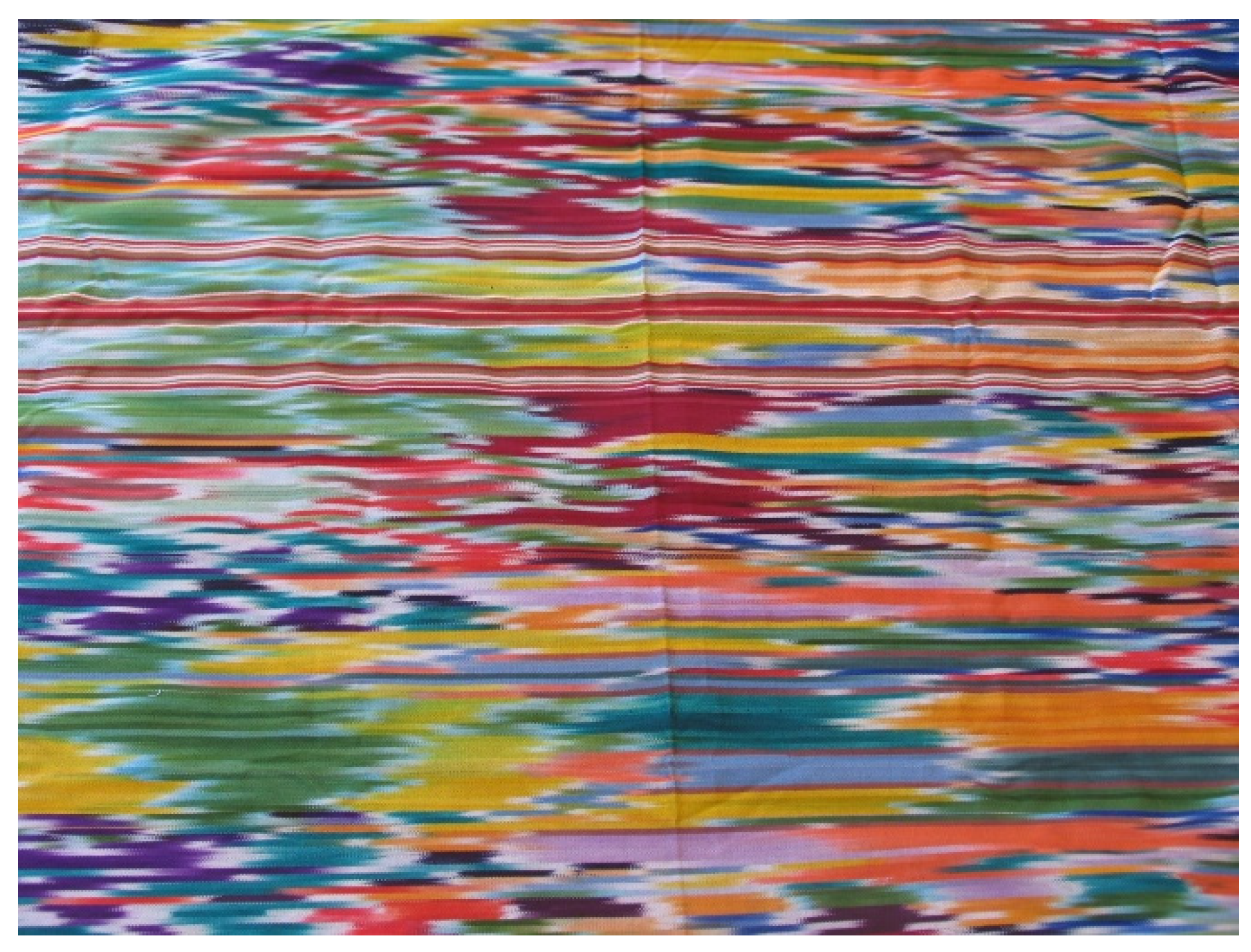

- Amiri, E.; Weaving Educator, Tehran, Iran. Unpublished collection of Daraibafi Images, 2009.

- Dehkhoda, A.A. Karkhaneh. In Loghat Nameh Dehkhoda Dehkhoda Dictionary; Tehran University Press: Tehran, Iran, 1958; p. 17962. [Google Scholar]

- Dehkhoda, A.A. Kargah. In Loghat Nameh Dehkhoda Dehkhoda Dictionary; Tehran University Press: Tehran, Iran, 1958; p. 17974. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, M.G. Living Core of the Future: Proposing New Approach for The Future of Residential Complex in Metropolitan Areas; University of Massachusetts Amherst: Amherst, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boudagh, M.; Ghaemmaghami, P. The Typology of Traditional Houses in Tabriz. In Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XII; Brebbia, C.A., Binda, L., Eds.; WIT Press: Billerica, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 87–98. ISBN 978-1-84564-526-7. [Google Scholar]

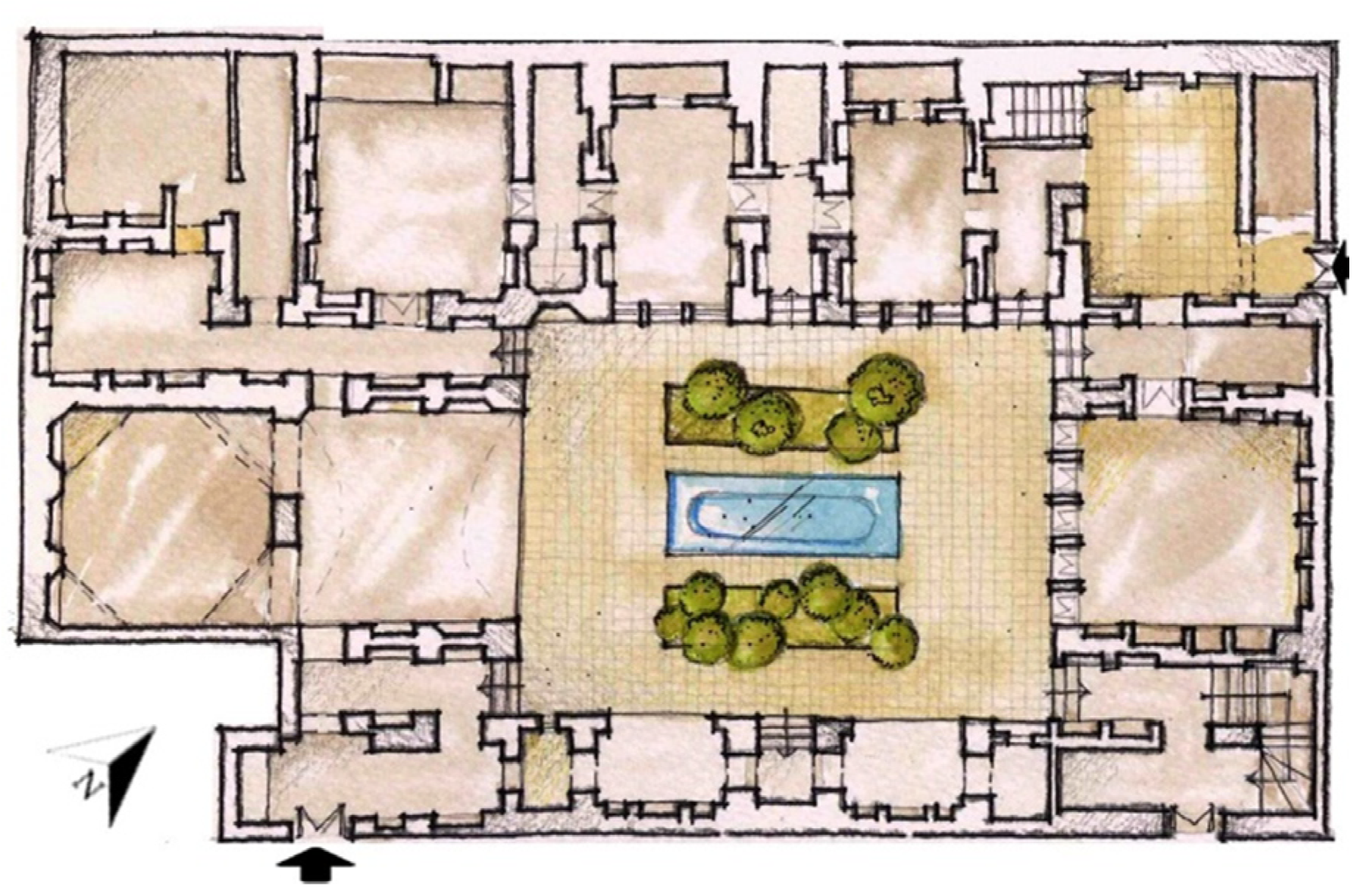

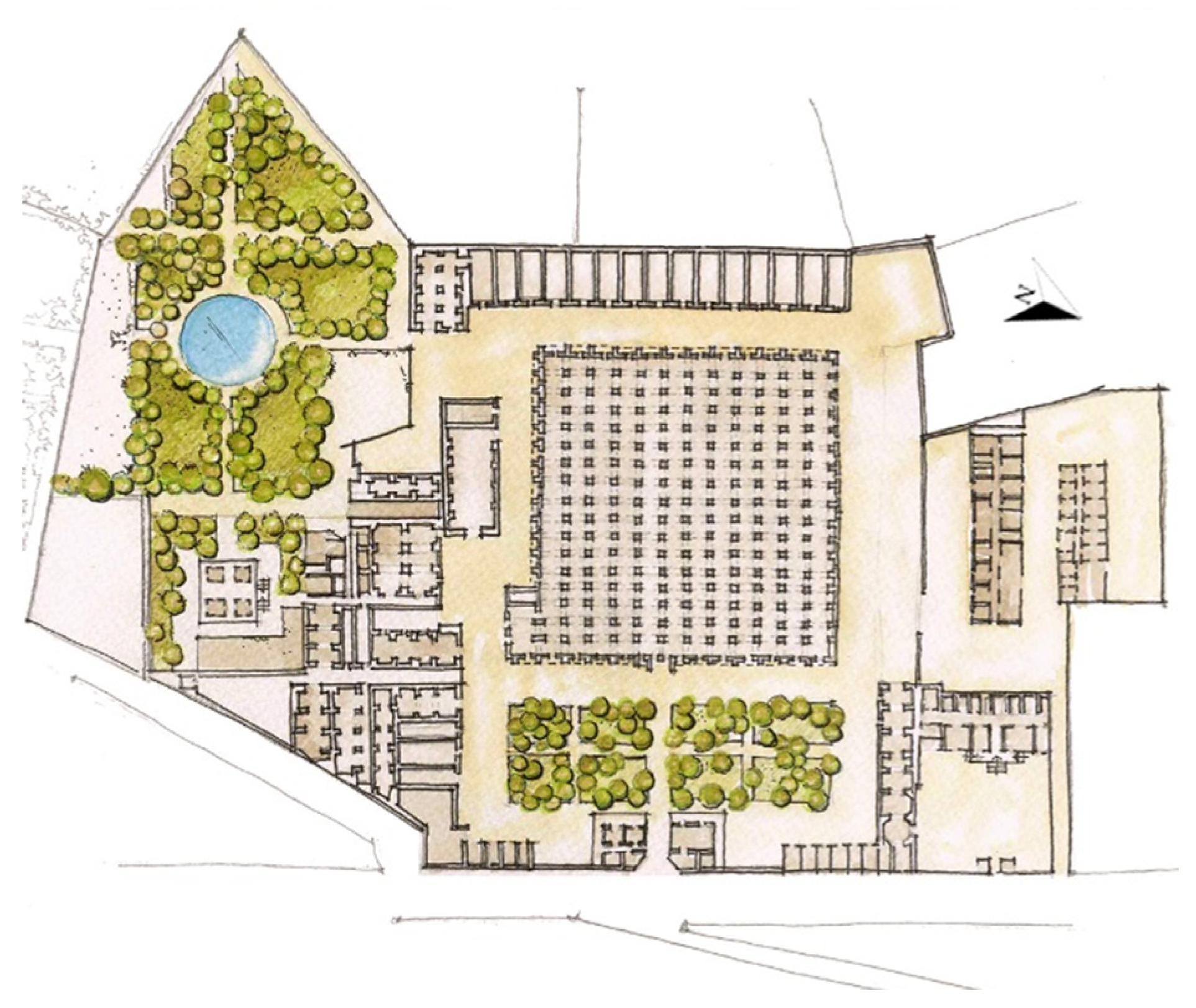

- Dehghan, H.; Owner of the Shaarbaf House Hotel, Yazd, Iran. Unpublished drawings of The Shaarbaf House by AutoCAD Software, the Ground Floor Drawing, 2014.

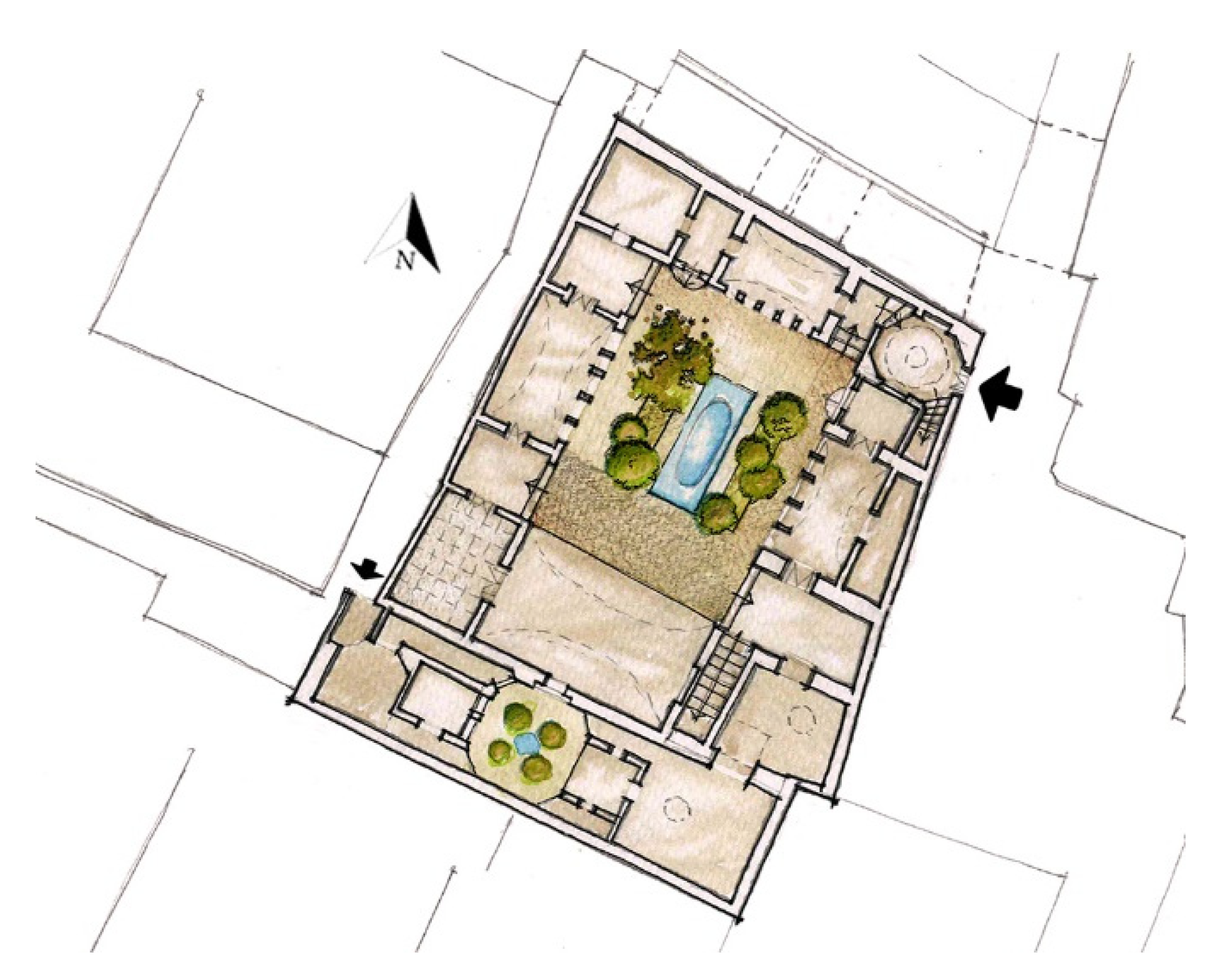

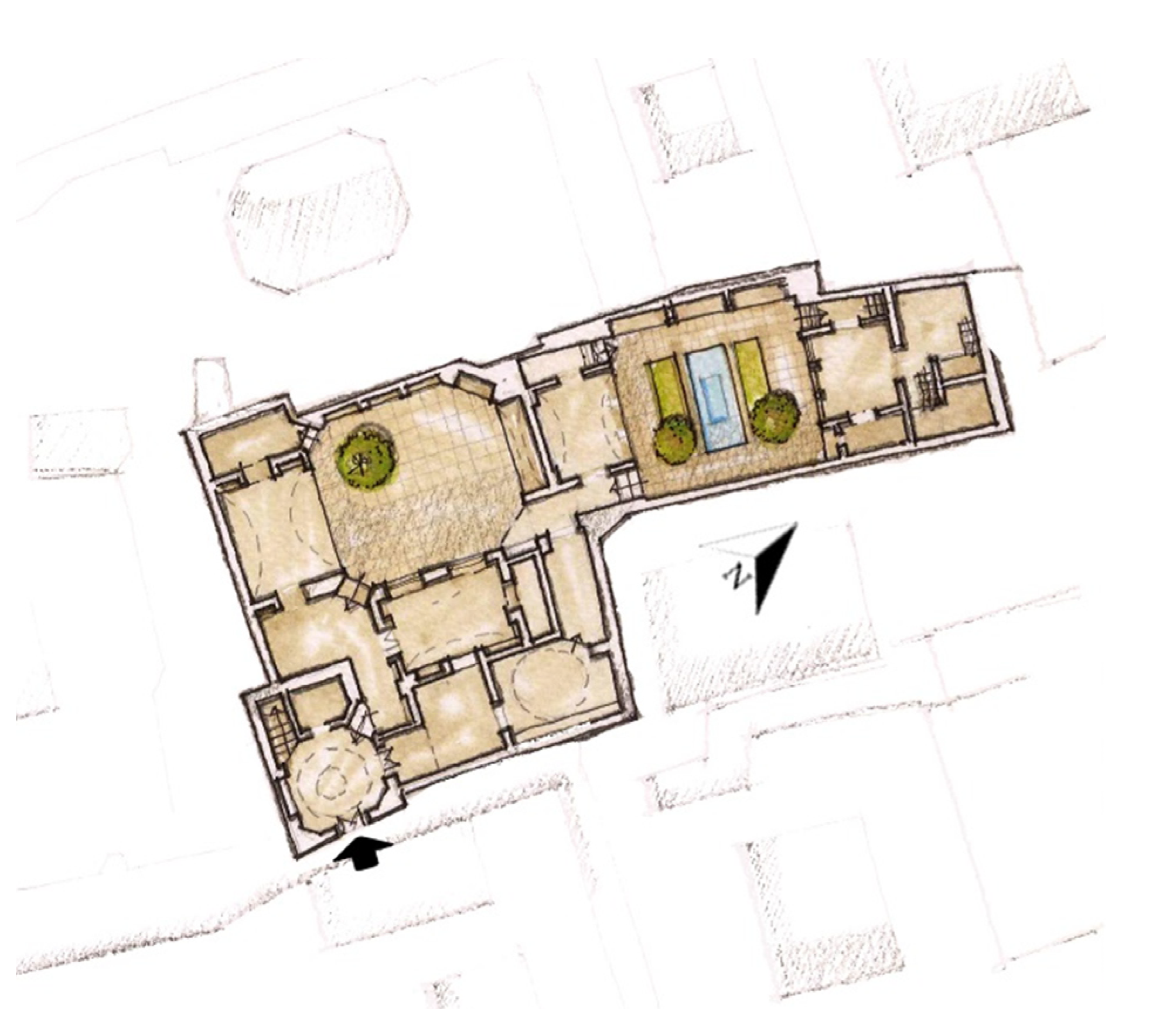

- Seddighikhavidak, S.; Instructor, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA. Unpublished watercolor sketches of Yazd Traditional Architecture, 2019.

- Ghazi, J.; Khezri, A.-R.; Attarzadeh, A.-K. A comparison of the structure and components of the entrance of religious and non-religious buildings of Kashan in Qājār Era. J. Hist. Islam. Civiliz. 2014, 46, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finastiian, M.; Torabi Farsani, N.; Mortazavi, M. Traditional Weaving House in Isfahan as a Museum for Promoting Last-Chance Tourism. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2019, 34, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staying of 850,000 tourists in Nowruz 97. 2018. Available online: http://portal.yazdcity.ir/ (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Mirhosseini, S.M. The Study of Industrial Clusters Performance in Islamic Republic of Iran (The Case Study of Yazd Textile Industrial Cluster). Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Maleksabet, M.; The main weaver and the owner of Maleksabet Family Daraibafi Karkhaneh, Yazd, Iran. Personal communication, 2019.

- Khademzadeh, M.H. Continuity and Change in the City of Yazd. In Iran: Architecture for Changing Societies; Jodidio, P., Ed.; Umberto Allemandi: Turin, Italy, 2006; pp. 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Seddighikhavidak, S.; Instructor, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA. Unpublished photos of Yazdi Karkhaneh Architecture. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maleksabet, G.; The main dyer in Maleksabet Dyeing Kargah, Yazd, Iran. Personal communication, 2019.

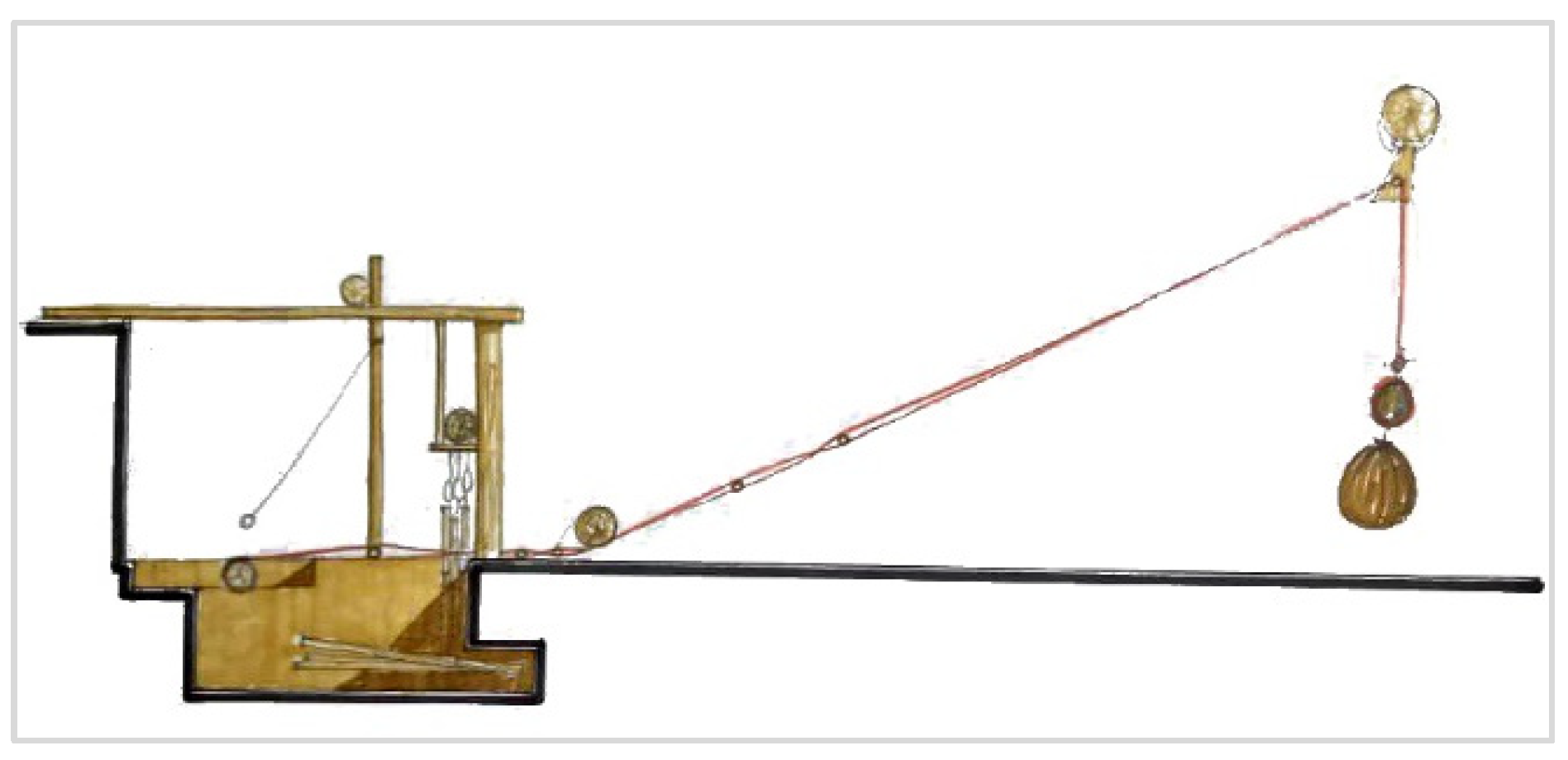

- Seddighikhavidak, S. Design of Yazd Daraei-Weaving Loom and Exhibition; University of Yazd: Yazd, Iran, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Seddighikhavidak, S.; Caffey, S.M. From Karkhaneh to Karkhaneh: From a Workroom to a Factory and Shaping a City. In Book of Abstracts, Proceedings of the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Southeast Chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Greenville, South Carolina, 9–12 October 2019; Southeast Chapter of the Society of Architectural Historians: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani-sanij, A.R.; Soltani, M.; Raahemifar, K. A New Design of Wind Tower for Passive Ventilation in Buildings to Reduce Energy Consumption in Windy Regions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reza, A.; Kors, G.R.; Shoushtari, M.A.; Entezami, A.A. Water and Technology of Irrigation in Ancient Iran; Ministry of Water and Electricity: Tehran, Iran, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Alamdaryazdi, A.; Mahmodi, M.M.; Mostafazadeh, M. Shaarbafi Kargahs in Yazd City; Yazd University: Yazd, Iran, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, H.; Zarei, A. Dorakhshan Factory: Record of Proposing the Register in National Monuments Lists; Yazd, Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization of Yazd Province (CHHTOY): Yazd, Iran, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Campagnol, G. The Place of the Industrial Past: The Adaptive Reuse of the Industrial Heritage in the Engenho Central de Piracicaba, Brazil. Built Environ. 2017, 43, 106–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan Pour Farashah, M.; Aslani, E.; Hosseini, M. Strategic Planning of Industrial Heritage Conservation in Yazd with Tourism Approach (Case Study: Textile Factories). In Proceedings of the International Conference on Conservation of 20th Century Heritage from Architecture to Landscape, Tehran, Iran, 23–24 April 2019; University of Tehran: Tehran, Iran, 2019. Available online: https://www.en.symposia.ir/ICCCHA01 (accessed on 21 May 2022).

- Ramazankhani, M.R. Regeneration of Industrial Heritage with Emphasis on Maintaining Cultural Values, Case Study: Spinning and Wrapping Factory of Nasadjan Yazd; University of Tehran: Tehran, Iran, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gorguie, H. Eghbal Factory: Record of Proposing the Register in National Monuments Lists; Yazd, Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization of Yazd Province (CHHTOY): Yazd, Iran, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmatzadeh, S. Saadat Factory: Record of Proposing the Register in National Monuments Lists; Yazd, Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization of Yazd Province (CHHTOY): Yazd, Iran, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzadi, D. Jonub Factory: Record of Proposing the Register in National Monuments Lists; Yazd, Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism Organization of Yazd Province (CHHTOY): Yazd, Iran, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bazazzadeh, H.; Nadolny, A.; Mehan, A.; Hashemi Safaei, S.S. The Importance of Flexibility in Adaptive Reuse of Industrial Heritage: Learning from Iranian Cases. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 12, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. Attributes of Tradition. In Dwellings, Settlements, and Tradition: Cross-Cultural Perspectives; Bourdier, J.-P., Alsayyad, N., Eds.; University Press of America: Lanham, MD, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, N. Resident Perceptions toward Tourism Impacts in Historic Center of Yazd, Iran. Tour. Geogr. 2017, 19, 734–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrolahi, A.; Roux, J.-M.; Ghasvarian Jahromi, L.; Khalili, M. Assessment of Local People Opinion after World Heritage Site Designation, Case Study: Historic City of Yazd, Iran. Heritage 2019, 2, 1739–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adib, A.; Habib, F. Strategic Planning for Spatial Development in the Historical Tissue of Yazd City with a Tourism Approach. Eur. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2016, 5, 595–605. [Google Scholar]

- Passanti, F. The Vernacular, Modernism, and Le Corbusier. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 1997, 56, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, C. Persian Local Histories: Views from the Wings. Iran. Stud. 2000, 33, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojasteh, M.; Professor and the owner of Khojasteh Daraibafi Kargah, Yazd Azad University, Yazd, Iran. Personal communication, 2019.

- Simoni, V. Tobacco’s Worlds: Tourism, Cigars, and the Shaping of Realities in Cuba. In Things That Move: The Material Worlds of Tourism and Travel; Picard, D., Robinson, M., Eds.; Leeds Metropolitan University: Leeds, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, A. Actor Network Theory. In Encyclopedia of Social Theory; Harrington, A., Marshall, B.I., Muller, H.P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- van der Duim, R.; Ren, C.; Thór Jóhannesson, G. Ordering, Materiality, and Multiplicity: Enacting Actor–Network Theory in Tourism. Tour. Stud. 2013, 13, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, M.; Jafarpour, G.K.; Hekmatnia, H.; Bagheri, K.A. Providing a Comprehensive Model of Inter-Sectoral Coordination with the Express Purpose of the Creative City Realization: Case Study of Yazd City. UXUC-User Exp. Urban Creat. 2020, 2, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guia, J.; Jamal, T. A (Deleuzian) Posthumanist Paradigm for Tourism Research. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Scale | Name | Neighborhood | Current Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Home domiciles | the Shaarbaf House | the Fahadan District | renovated and reused |

| the Haghighat House | the Fahadan District | in the process of renovation | |

| the Ra’sol-hoseini House | the Fahadan District | renovated and reused as a textile museum | |

| unnamed (I) | the Lard-e-asiab District | abandoned and ruined | |

| unnamed (II) | the Lard-e-asiab District | abandoned and ruined | |

| unnamed (III) | the Lard-e-asiab District | active—Foreign workers living here | |

| the Padiav House | the Baazar-e-no District | renovated and reused as a hotel | |

| the Arabshahi House | the Shah Abolqasem District | renovated | |

| the Doost (Friend) House | the Shah Abolqasem District | renovated and reused as a hotel | |

| the Ranjbar House | the Sar-e Jam District | abandoned | |

| unnamed | the Sar-e Jam District | active—living and working (textile weaving) | |

| unnamed | the Sheykhdad District | active—living | |

| unnamed | the Fahadan District | active—living and working (textile weaving) | |

| the Baghaiepour House | near the Gazorgah District | active—living and working (textile weaving) | |

| the Peyvandi House | near the Gazorgah District | active—living and working (textile weaving) | |

| Local neighborhood | unnamed kargah | near Kamalieh Madreseh in the Fahadan District | ruined |

| the Khojasteh Daraibafi Kargah (I) | the Vaght-o-saa’t District | active—working (textile weaving) and selling textile products | |

| the Khojasteh Daraibafi Kargah (II) | the Vaght-o-saa’t District | renovated | |

| Maleksabet Family Daraibafi Kargah | the Yaghoubi District | active—working (textile weaving) | |

| Karkhaneh-ye-sefid: Yazd Sefid Textile Econo-Museum | the Baazar-e-no District | part of it is renovated as a textile museum | |

| unnamed kargah | near to Kooshk-e-No Water Cistern in the Kooshk-e-No District | abandoned | |

| unnamed kargah | the Lard-e-asiab District | abandoned and ruined | |

| the Azadi Kargah | the Fahadan District | selling textile products | |

| Malek Daraibafi Kargah | the Fahadan District | active—living, working (textile weaving) and selling textile products | |

| City of Yazd | the Eghbal Factory | the Sar-e Dorah District | renovated and reused as the Yazd Science Technology Park |

| the Saadat Factory | near to the Fahadan District | renovated | |

| the Dorakhashan Factory | Near to Zartoshtiha District | abandoned and ruined | |

| the Jonub factory | out of Historic city of Yazd | renovated and reused as seasonal exhibitions |

| Establishment Year | Current Condition | View | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eghbal | 1931 | Renovated and reused |  |

| Source: Hossain Gorgui, 2002 [48] (p. 8) | |||

| Saadat Nasadjan | 1934 | Renovated and reused |  |

| Source: Alireza Rahmani, 2012 [49] (p. 9) | |||

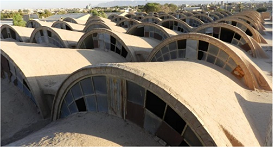

| Dorakhshan (Herati) | 1935 | Abandoned and ruined |  |

| Source: Hamidreza Amiri, 2005 [44] (p. 32) | |||

| Seyed-Mohammad Agha | 1948 | Abandoned | |

| Dastbafan | 1948 | Abandoned | |

| YazdBaf | 1956 | Active | |

| Jonub | 1959 | Renovated and reused |  |

| Source: Dinyar Shahzadi, 2003 [50] (p. 20) | |||

| Afshar | 1963 | Active |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seddighikhavidak, S.; Jamal, T. Interrelations of Ancestral Textile Handicraft Weaving and Tangible Vernacular Karkhanehs (Workspaces) in the Historic Destination of Yazd, Iran. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106363

Seddighikhavidak S, Jamal T. Interrelations of Ancestral Textile Handicraft Weaving and Tangible Vernacular Karkhanehs (Workspaces) in the Historic Destination of Yazd, Iran. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):6363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106363

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeddighikhavidak, Somaye, and Tazim Jamal. 2022. "Interrelations of Ancestral Textile Handicraft Weaving and Tangible Vernacular Karkhanehs (Workspaces) in the Historic Destination of Yazd, Iran" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 6363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106363

APA StyleSeddighikhavidak, S., & Jamal, T. (2022). Interrelations of Ancestral Textile Handicraft Weaving and Tangible Vernacular Karkhanehs (Workspaces) in the Historic Destination of Yazd, Iran. Sustainability, 14(10), 6363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106363