Do FDI Inflows and ICT Affect Economic Growth? An Evidence from Arab Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- Information and communication technology has a positive and moral impact on foreign direct investment in the short and long terms in the Arab countries under study.

- -

- Information and communications technology and foreign direct investment have a positive and moral impact on economic growth in the short and long terms in the Arab countries under study.

- -

- Foreign direct investment and economic growth positively and morally affect information and communication technology in the short and long term in the Arab countries under study.

2. Information and Communication Technology in the Arab Countries

3. Literature Review

3.1. Theoretical Framework

3.2. Empirical Framework

4. Research Data and Methodology

4.1. Data

4.2. Methods

- GDPC: GDP per capita (at constant 2010 USD).

- FDI: FDI inflows as a percentage of GDP.

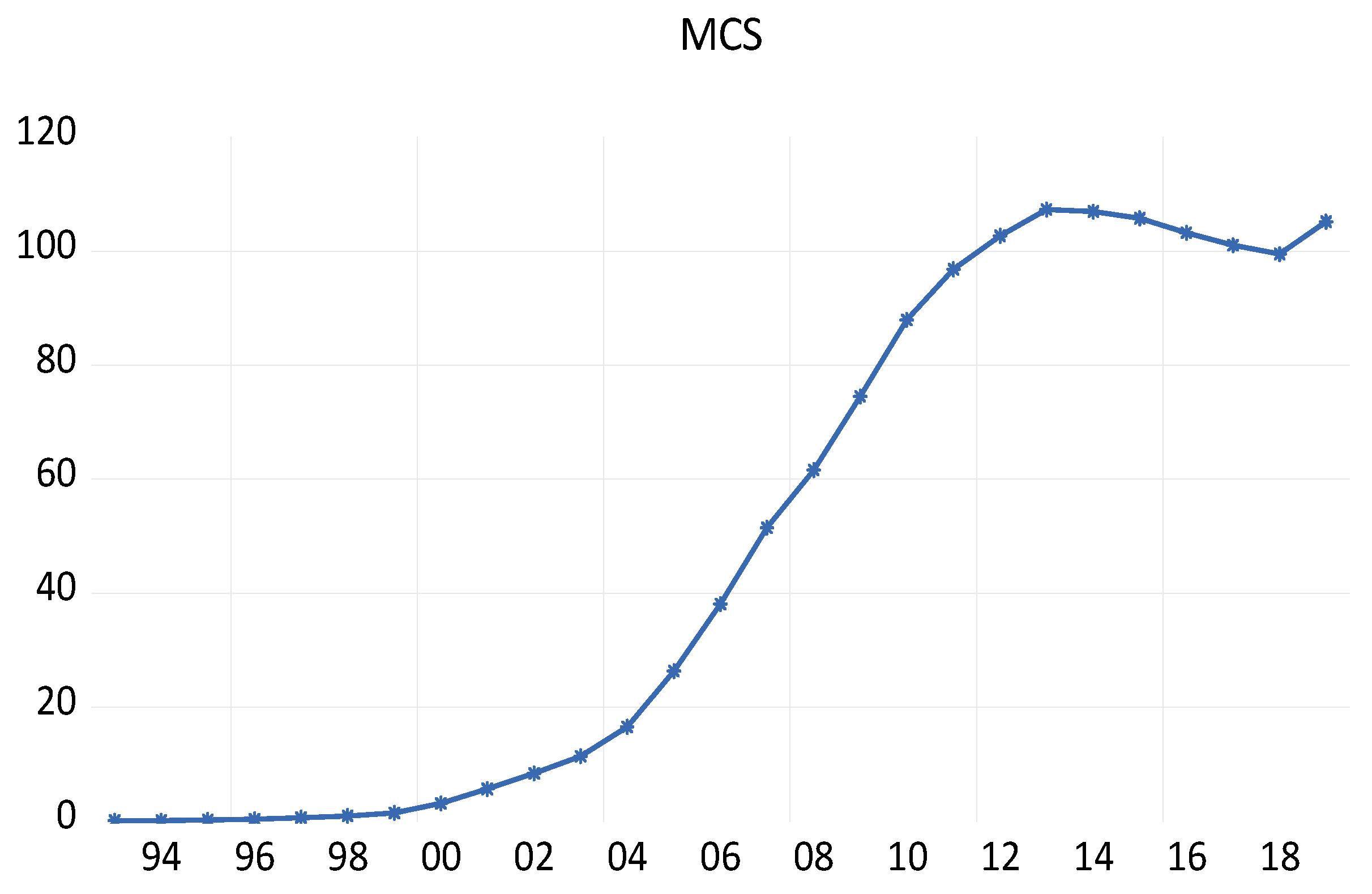

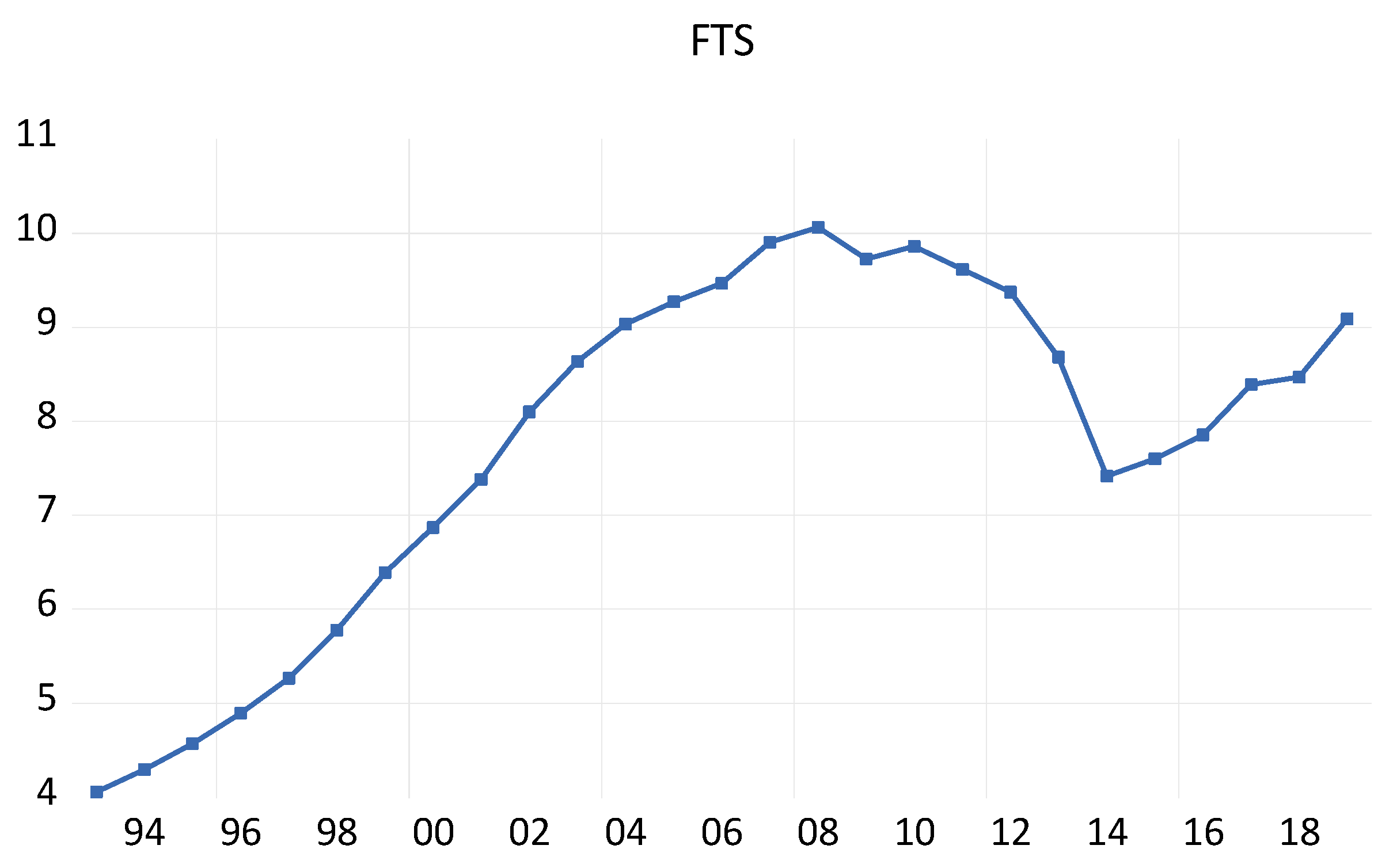

- ICT: Information and Communication Technology. It is represented here by three variables: the percentage of internet users, the number of mobile phone subscriptions per 100 people, and the number of fixed phone subscriptions per 100 people (PIUI, MCS, and FTS, respectively).

- The index (i = 1,…, N) i refers to the country i of our sample (N = 15).

- The index (t = 1,…, T) t represents the period or years (T = 25).

- β0, β1 and β2: parameters to be estimated.

- µi: These are the country-specific fixed effects.

- εit: This is the random error term.

- Φi is the group’s adaptive velocity coefficient (

- ϑ and ρ: represent the coefficients that measure the effect of the independent variables on the dependent variable in the long run.

- δij and γij: They are the coefficients that represent the effect of the independent variables on the dependent variable in the short run.

- μi: They are the fixed effects that represent the specifies of each country, and they do not change in time.

- εit: This is the random error term.

5. Result Analysis

5.1. Results of Unit Root Tests and Cointegration Tests

5.2. Analysis of The Results of Panel ARDL Model

6. Main Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable Symbol | Variable Name | Variable Definition |

|---|---|---|

| GDPC | GDP per capita | GDP per capita at constant 2010 prices in US dollars. GDP is the sum of the total value added of all resident producers in the economy, plus any product taxes, minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products. |

| FDI | FDI inflows | The percentage of net inflows of foreign direct investment from the gross domestic product. Foreign direct investment refers to the flows of direct investment shares in the economy. It is the sum of equity capital, revenue reinvestment, and other capital. Direct investment is a category of cross-border investment associated with a resident of one economy who has control or significant influence over the management of an enterprise that is resident in another economy. |

| FTS | The number of fixed-line subscriptions | The number of fixed-line subscriptions per 100 people. |

| MCS | Number of mobile phone subscriptions | The number of mobile phone subscriptions per 100 people. |

| PIUI | Percentage of Internet users | The percentage of individuals who use the Internet out of the total population. |

Appendix B

| GDPC | FDI | PIUI | MCS | FTS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 11,936.57 | 2.96 | 26.27 | 64.73 | 10.58 |

| Median | 4221.84 | 2.001 | 14.90 | 59.472 | 9.334 |

| Maximum | 64,864.74 | 33.56 | 99.70 | 212.63 | 32.87 |

| Minimum | 632.90 | −11.62 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.256 |

| Standard deviation | 14,923.72 | 4.325 | 29.15 | 57.245 | 7.655 |

| observations | 375 | 375 | 375 | 375 | 375 |

Appendix C

| Correlation T Stat p-Value | LGDPC | FDI | PIUI | MCS | FTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGDPC | 1 - - | - | - | - | - |

| FDI | −0.035 −0.693 0.488 | 1 - - | - | - | - |

| PIUI | 0.444 * 9.59 0.00 | −0.030 −0.585 0.55 | 1 - - | - | - |

| MCS | 0.427 * 9.14 0.00 | 0.022 0.428 0.66 | 0.857 * 32.21 0.00 | 1 - - | - |

| FTS | 0.847 * 30.84 0.00 | 0.091 *** 1.768 0.07 | 0.354 * 7.31 0.00 | 0.283 * 5.69 0.00 | 1 - - |

References

- Sinha, M.; Sengupta, P.P. FDI Inflow, ICT Expansion and Economic Growth: An Empirical Study on Asia-Pacific Developing Countries. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2019, 23, 804–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bon, A.; Akkermans, J.M.; Gordijn, J. Developing ICT Services in a Low-Resource Development Context. Complex Syst. Inform. Modeling Q. CSIMQ 2016, 9, 84–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Yang, S. Information Technology and productivity: A review of the literature. Adv. Comput. 1966, 43, 179–214. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrini, R.; Qaffas, A. Impact of Information and Communication Technology on Economic Growth: Evidence from Developing Countries. Economies 2019, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dimelis, S.P.; Papaioannou, S.K. FDI and ICT effects on productivity growth: A comparative analysis of developing and developed countries. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2010, 22, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measuring the Information Society Report; International Telecommunication Union: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- World Development Indicators (WDI); The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Solow, R.M. A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Endogenous technological change. J. Political Econ. 1990, 98, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pohjola, M. The New Economy: Facts, Impacts and Policies. Inf. Econ. Policy 2002, 14, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, E.H.; Aghaei, M. The Effect of ICT on Economic Growth: Further Evidence. Int. Bull. Bus. Adm. 2009, 5, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sarangi, A.K.; Pradhan, R.P. ICT infrastructure and economic growth: A critical assessment and some policy implications. Decision 2021, 47, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addison, T.; Heshmati, A. The New Global Determinants of FDI Flows to Developing Countries: The Importance of ICT and Democratization. Res. Bank. Financ. 2004, 4, 151–186. [Google Scholar]

- Matambalya, F.; Wolf, S. Performance of SMEs in East Africa: Case Studies from Kenya and Tanzania; Center for Development Research, ZEF: Bonn, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pajarinen, M.; Ylä-Anttila, P. Countries Compete for Investment-Finnish Technology Attracts Foreign Firms; ETLA B 173; Taloustieto Oy: Helsinki, Finland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Clemons, E.; Row, M. Sustaining IT Advantage: The Role of Structural Differences. MIS Q. 1991, 15, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbaxani, V.; Whang, S. The Impact of Information Systems on Organizations and Markets. Commun. ACM 1991, 34, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, L.M. Information Technology and Firm Boundaries: Evidence from Panel Data. Inf. Syst. Res. 1999, 10, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jorgenson, D.W. Information Technology and the US Economy. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kraemer, K.L.; Dedrick, J. Payoffs from Investment in Information Technology: Lessons from the ASIA-PACIFIC Region. World Dev. 1994, 22, 1921–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dewan, S.; Kraemer, K. International dimension of the productivity paradox. Commun. ACM 1998, 41, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohjola, M. Information Technology and Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Analysis; Working Paper No. 173; The United Nations University: Tokyo, Japan, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, S.; Kraemer, K. Information Technology and Productivity: Evidence from Country-Level Data; Center for Research on Information Technology, University of California: Irvine, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgenson, D.W.; Stiroh, K.J. Raising the Speed Limit: US Economic Growth in the Information Age. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2000, 2000, 125–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joseph, K.J. Growth of ICT and ICT for Development—Realities of the Myths of the Indian Experience; Discussion Paper No. 2002/78; UNU/WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, K.L.; Dedrick, J. IT-Led Development in Singapore: From Winchester Island to Intelligent Island; Working Paper #ITR-123; Center for Research on Information Technology and Organizations, Graduate School of Management, University of California: Irvine, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Oliner, S.D.; Sichel, D.E. The Resurgence of Growth in the Late 1990s: Is Information Technology the Story? J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tallon, P.P.; Kraemer, K.L. Information technology and economic development: Ireland’s coming of age with lessons for developing countries. J. Glob. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2000, 3, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gholami, G.; Tom, L.S.; Heshmati, A. The Causal Relationship between Information and Communication Technology and Foreign Direct Investment; Discussion Paper No. 2003/30; UNU/WIDER: Helsinki, Finland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Blomstrom, M.; Kokko, A.; Globerman, S. The Determinants of Host Country Spillovers from Foreign Direct Investment: A Review and Synthesis of the Literature. In Inward Investment, Technological Change, and Growth; Pain, N., Ed.; Palgrave: Basingstoke, UK, 2001; pp. 34–65. [Google Scholar]

- Guetat, I.; Drine, I. The Information and Communication Technologies Impact on MENA Countries Growth Performance. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference of the MEEA, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 14–16 March 2007; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Sassi, S.; Goaied, M. Financial development, ICT diffusion and economic growth: Lessons from MENA region. Telecommun. Policy 2013, 37, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Habib, T. The Impact of Information and Communication Technology on Economic Growth in Developing Countries: A Record Study during the Period 2005–2015. J. Econ. Financ. Res. Umm El Bouaghi Larbi Ben M’hidi Univ. 2018, 5, 559–580. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Sharekh, N.; Hamdan, B. The Impact of Investment in Information and Communication Technology on Palestinian Economic Growth. J. Manag. Econ. Res. Djelfa Xian Ashour Univ. 2019, 1, 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Alshubiri, F.; Jamil, S.A.; Elheddad, M. The impact of ICT on financial development: Empirical evidence from the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 1847979019870670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghaed, E.; Heidari, H.; Goltapeh, M.R. The Impact of Information and Communication Technology (ICT), Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and General Government Expenditures on the Economic Growth of MENA Countries. Iran. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 1, 58–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hussein, E. The Impact of Information and Communication Technology on Inclusive Growth: An Applied Study on Developing and Arab Countries. J. Fac. Econ. Political Sci. Cairo Cairo Univ. 2020, 21, 3–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.H.; Choi, C.H. Has the Internet increased FDI, economic growth, and trade? Evidence from Asian economies. Inf. Dev. 2021, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, M.A. Analysis of the impact of information communication technology on economic growth: Empirical evidence from Asian countries. J. Asian Bus. Econ. Stud. 2021, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Sahoo, D. FDI inflow, ICT and economic performance of India: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2021; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Soomro, A.N.; Kumar, J.; Kumari, J. The Dynamic Relationship Between FDI, ICT, Trade Openness, and Economic Growth: Evidence from BRICS Countries. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2022, 9, 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Peizhi, G.; Bangash, G.R. The Effect of Information Communication Technology (ICT) Infrastructure Availability on FDI Inflow in D8 Countries. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 235, 02052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, W.H. Computers and Society. In The International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; Elsevier Science Limited: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 2480–2487. [Google Scholar]

- Peracchi, F. Econometrics; Wiley: West Sussex, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Im, K.S.; Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J. Econom. 2003, 115, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Lin, C.-F.; Chu, C.S.J. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J. Econom. 2002, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I. Unit root tests for panel data. J. Int. Money Financ. 2001, 20, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. J. Econom. 1999, 90, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. Critical values for cointegration tests in heterogeneous panels with multiple regressors. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 1999, 61 (Suppl. S1), 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. Panel cointegration: Asymptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series tests with an application to the PPP hypothesis. Econom. Theory 2004, 20, 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M.; Alse, S. Export Growth and Economic Growth: An application of cointegration and error correction modeling. J. Dev. Areas 1993, 27, 535–542. [Google Scholar]

- Kazem, K.A. The Problem of the Relationship between the Rentier Economy and the Rentier State; The Civilized Dialog: Kazem, Kamel Allawi, 2013; Volume 25, p. 4155. [Google Scholar]

- Qurm, G. In a Critique of the Arab Rentier Economy; Center for Arab Unity Studies: Beirut, Lebanon, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.P. Pooled Mean Group Estimation of Dynamic Heterogeneous Panels. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999, 94, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Smith, R. Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. J. Econom. 1995, 68, 79–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | ICT Development Index in 2017 | Regional Ranking in 2017 | ICT Development Index in 2017 | Regional Ranking in 2017 | Change in ICT Development Index 2011–2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahrain | 7.6 | 1 | 5.79 | 2 | 1.81 |

| Qatar | 7.21 | 2 | 6.41 | 1 | 0.8 |

| United Arab Emirates | 7.21 | 3 | 5.68 | 3 | 1.53 |

| Saudi Arabia | 6.67 | 4 | 5.46 | 4 | 1.21 |

| Oman | 6.43 | 5 | 4.8 | 5 | 1.63 |

| Lebanon | 6.3 | 6 | 4.62 | 6 | 1.68 |

| Jordan | 6 | 7 | 3.9 | 7 | 2.1 |

| Tunisia | 4.82 | 8 | 3.57 | 10 | 1.25 |

| Morocco | 4.77 | 9 | 3.59 | 9 | 1.18 |

| Algeria | 4.67 | 10 | 2.98 | 12 | 1.69 |

| Egypt | 4.63 | 11 | 3.64 | 8 | 0.99 |

| Syria | 3.34 | 12 | 3.12 | 11 | 0.22 |

| Sudan | 2.55 | 13 | 2.18 | 13 | 0.37 |

| Djibouti | 1.98 | 14 | 1.71 | 14 | 0.27 |

| Comoros | 1.82 | 15 | 1.68 | 15 | 0.14 |

| Variable | Statistics of Tests | Order of Integ. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLC Test | IPS Test | ADF-Fisher Test | PP-Fisher Test | ||||||

| H0: Common Unit Root | H0: Individual Unit Root | ||||||||

| At Level | At First Level | At Level | At First Level | At Level | At First Level | At Level | At First Level | ||

| LGDPC | −0.497 | −4.50 * | 0.437 | −5.59 * | 30.92 | 84.68 * | 12.82 | 108.6 * | I (1) |

| FDI | −3.56 * | - | −5.60 * | - | 88.51 * | - | 88.00 * | - | I (0) |

| PIUI | 3.51 | −3.43 * | 9.30 | −4.82 * | 3.76 | 95.27 * | 0.85 | 138.2 * | I (1) |

| MCS | 0.541 | −3.92 * | −0.872 | −4.09 * | 32.61 | 66.01 * | 7.60 | 76.77 * | I (1) |

| FTS | −3.22 * | −5.48 * | −1.96 ** | −7.21 * | 50.83 * | 113.15 * | 32.50 | 216.5 * | I (0) or I (1) |

| LGDPC | FDI | MCS | PIUI | FTS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedroni Residual Cointegration Test | |||||

| Alternative Hypothesis: Common AR Coefs. (Within-Dimension) | |||||

| Panel v-Statistic | −4.41 * | −3.22 * | −1.79 *** | −0.98 | −1.92 *** |

| Panel rho-Statistic | −1.02 | −0.79 | −0.36 | −0.53 | −0.17 |

| Panel PP-Statistic | −7.45 * | −6.21 * | −2.44 ** | −1.85 *** | −2.51 ** |

| Panel ADF-Statistic | −8.66 * | −6.74 * | −2.51 ** | −1.94 *** | −2.63 ** |

| Pedroni Residual Cointegration Test | |||||

| Alternative Hypothesis: Individual AR Coefs. (Between-Dimension) | |||||

| Group rho-Statistic | −1.02 | −0.79 | −0.36 | −0.53 | −0.17 |

| Group PP-Statistic | −7.71 * | −6.35 * | −2.29 ** | −1.78 *** | −2.55 ** |

| Group ADF-Statistic | −8.44 * | −6.88 * | −2.61 ** | −1.84 *** | −2.59 ** |

| Kao Cointegration Test | |||||

| Augmented Dickey Fuller | −5.67 * | −4.58 * | −0.81 | −1.95 *** | −2.78 ** |

| Dep. Var. | LGDPC | FDI | FTS | MCS | PIUI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMG vs. MG | PMG vs. DFE | PMG vs. MG | PMG vs. DFE | PMG vs. MG | PMG vs. DFE | PMG vs. MG | PMG vs. DFE | PMG vs. MG | PMG vs. DFE | |

| Chi-squared statistic | 1.60 | 1.73 | 1.14 | 1.65 | 7.23 | 8.56 | 1.62 | 0.00 | 1.17 | 0.00 |

| p-value | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.00 |

| Decision | The null hypothesis of homogeneity cannot be rejected | |||||||||

| Best model | PMG estimation | |||||||||

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable: D (LGDPC) |

|---|---|

| Use of the ICT Index: Proportion of Individuals Using the Internet | |

| Long run coefficients | |

| FDI | 0.025 * |

| PIUI | 0.003 * |

| Short run coefficients | |

| ECT | −0.155 * |

| D(FDI) | −0.005 |

| D(PIUI) | 0.001 |

| Use of the ICT Index: Number of Mobile Subscriptions per 100 Individuals | |

| Long run coefficients | |

| FDI | 0.018 * |

| MCS | 0.0002 |

| Short run coefficients | |

| ECT | −0.211 * |

| D(FDI) | −0.004 |

| D(MCS) | 0.001 |

| Use of the ICT Index: Number of Fixed Telephone Subscriptions per 100 Individuals | |

| Long run Coefficients | |

| FDI | 0.026 * |

| FTS | 0.048 * |

| Short run coefficients | |

| ECT | −0.088 * |

| D (FDI) | −0.004 |

| D (FTS) | 0.005 |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variable: D (FDI) |

|---|---|

| Use of the ICT Index: Proportion of Individuals Using the Internet | |

| Long run coefficients | |

| LGDPC | 3.14 * |

| PIUI | 0.059 * |

| Short run coefficients | |

| ECT | −1.31 * |

| D (LGDPC) | 7.44 |

| D (PIUI) | 0.302 |

| Use of the ICT Index: Number of Mobile Subscriptions per 100 Individuals | |

| Long run coefficients | |

| LGDPC | 0.174 * |

| MCS | 0.001 * |

| Short run coefficients | |

| ECT | −1.061 * |

| D (LGDPC) | −2.30 |

| D (MCS) | 0.069 |

| Use of the ICT Index: Number of Fixed Telephone Subscriptions per 100 Individuals | |

| Long run coefficients | |

| LGDPC | 0.207 * |

| FTS | 0.026 ** |

| Short run coefficients | |

| ECT | −0.623 * |

| D (LGDPC) | 29.28 |

| D (FTS) | −1.302 *** |

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| D (MCS) | D (PIUI) | D (FTS) | |

| Long run coefficients | |||

| LGDPC | 57.04 * | 6.45 * | 0.11 * |

| FDI | 5.83 * | 19.42 * | 1.92 * |

| Short run coefficients | |||

| ECT | −0.09 * | −0.02 | −0.83 * |

| D(LGDPC) | 11.80 | −0.54 | −2.93 |

| D(FDI) | −0.36 | −1.07 | −0.01 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Belloumi, M.; Touati, K. Do FDI Inflows and ICT Affect Economic Growth? An Evidence from Arab Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106293

Belloumi M, Touati K. Do FDI Inflows and ICT Affect Economic Growth? An Evidence from Arab Countries. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):6293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106293

Chicago/Turabian StyleBelloumi, Mounir, and Kamel Touati. 2022. "Do FDI Inflows and ICT Affect Economic Growth? An Evidence from Arab Countries" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 6293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106293

APA StyleBelloumi, M., & Touati, K. (2022). Do FDI Inflows and ICT Affect Economic Growth? An Evidence from Arab Countries. Sustainability, 14(10), 6293. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106293