Abstract

This study examines the impact of microfinance on the social performance of local households in the Kassena Nankana East District of northern Ghana. The study’s primary objective was to measure the average effect of the common social performance framework’s core indicators (outreach and products and services) on beneficiaries. Because the social performance management framework is an institutional-based evaluation, it is silent on changes in the service users’ lives. This study modified the common social performance management framework to treat outreach and products and services as independent variables, with changes in the lives of service users as the only output or result. We narrowed these indicators to outreach and mobile banking, and under products and services, we concentrated on nonfinancial products and services because, in microfinance, nonfinancial services lack the needed attention. This study employed the propensity score matching (PSM) method to measure the average treatment effect of the independent variables (outreach, mobile banking, and training) by using data from 341 client households. In the absence of a random assignment of treatment conditions, we placed client households who received these three treatments in a treatment group and those who did not receive such treatments in a control group. We further used the PSM method to match observations of households in the treatment group (households who have access to mobile banks, MFI outreach, and training) with those in the control group (households without access to those) by creating the conditions of an experiment where the treatment elements are randomly assigned to avoid any possible bias. The results showed that outreach significantly decreased loan disbursement time. Conversely, outreach was not significant in relation to delayed loan disbursement time. Mobile banking was statistically significant for increased income, business expansion, timely loan disbursement, and high cost of loans. On the contrary, mobile banking was significantly negative in relation to delayed loan disbursement time. Training showed a significant correlation with women’s empowerment, household decision making, and political and community participation. Regarding the impact of training on the use of a loan, the value of loans for consumption was negative, whereas for production it was positive. Despite the general acceptance of the common framework to measure microfinance social performance, there is still little work to prove the relationship between the framework’s output variables and changes in the lives of the service users. This paper is the first to provide empirical evidence on the impact of outreach and training on change variables. The implication of this paper is that nonfinancial services are equally crucial to delivering change for microfinance service users. Therefore, policymakers must find ways to incorporate essential nonfinancial products and services as bundle packages with credit. Additionally, mobile banking has a high potential for addressing challenges with remote outreach and adverse selection, which is a primary obstacle preventing many poor people from accessing credit.

1. Introduction

Countries with efficient strategies for delivering credit to the poor and informal sectors experience low poverty rates. Fair and efficient financial opportunities ensure equitable national development. Hence, compelling microcredit delivery assemblages such as microfinance remain significant for developing economies with limited financial prospects at the micro-economy level [1]. It is no wonder that microfinance continues to receive massive support for delivering financial services to vulnerable populations [2]. Despite tremendous regulatory and financial support, measuring microfinance institution (MFI) operations remain limited, especially in Africa, where development aid remains proportionately high.

Moreover, a surge in subsidies and investment has increased the demand for accountability. This is clearly evident with institutionalized financial accountability championed by profit-oriented investors with support from international financial institutions, financial service regulators, and policy makers [3]. Meanwhile, the same cannot be said for measuring microfinance social performance [4,5,6].

Microfinance has a dual bottom-line goal: serving the vulnerable population to reduce poverty and for MFIs to sufficiently profit to remain sustainable [7,8,9]. Critics believe that too much focus remains on the latter, whereas the former is ignored. Indeed, proponents of social impact measurement do not dispute the volumes of direct impact studies on health, education, and other economic benefits for clients (Mtamakaya et al. [10], Imai and Azam [11], Kumah and Boachie [12], Viswanath [13] Becchetti and Conzo [14]). The contention is the ability of microfinance to serve the very poor (depth of outreach) and to deliver other wider benefits such as social capital, political participation, and empowerment of women [3,9,15,16]. These concerns have led to recent scrutiny, criticism, and demand for social impact accountability. Some authors believe that the complexity and expense of measuring wider social benefits is the primary obstacle hindering profit-seeking microfinance providers and commercial MFIs from measuring social impact [9,17].

Nonetheless, suppose microfinance fulfills its social mission to ascertain the level of outreach to the core poor and to know how wider benefits could enhance poverty reduction. In that case, it remains essential to implement and evaluate social performance management in microfinance [9]. Therefore, this study attempts to measure the impact of microfinance social performance on beneficiaries. The paper’s objective is to estimate the treatment effect of the output indicators of the standard framework of social performance management (outreach and product and services) on the lives of service users.

Social performance management is defined as the “effective translation of institutions mission into practice in line with social values”. An institutional evaluation approach primarily aims to evaluate how an organization’s intent and process lead to it achieving its social goals: Thus, the impact on the service users is silent. Ordinarily, the framework treats outreach and products and services as output indicators. Nonetheless, this study adds a novel approach by modifying the common social performance management framework to treat outreach and products and services as independent variables, with changes in the lives of service users as the only output or result. In addition, we utilized nonfinancial products and services because they are treated as nonessential services that only add cost to MFIs. This is the first microfinance social performance evaluation to co-currently test the effect of outreach and nonfinancial products and services on service users to the best of our knowledge.

To achieve our objectives, the paper tests three hypotheses. First, the primary meaning of outreach is extending financial accessibility to many poor people, and according to [18,19], outreach helps reduce poverty among destitute people. Therefore, we draw our first hypothesis based on the theory that outreach is significant to poverty.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Outreach is positively significant to poverty.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Mobile banking positively affects poverty variables. This hypothesis is premised on the ideology that innovation affects increased productivity, which impacts revenue and income, leading to poverty reduction [20,21].

Haider et al. [22] and Hrader [23] conclude that training is significant to poverty reduction. In conformity, Peprah et al. [24] opine that financial accompaniment such as training is vital to the fight against poverty. Therefore, we form our third hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Training is significantly positive to poverty variables.

The choice of Ghana is interesting. As with many developing economies, most of Ghana’s working population is in the informal sector. Therefore, the general perception is that the advent of microfinance will contribute to equal financial service opportunities and eventually reduce poverty. Nonetheless, Ghana’s MFI sustainability and poverty reduction ability have received massive criticism over the years [25,26,27]. For example, in 2015, some eight MFIs had their licenses revoked over suspected Ponzi schemes. In 2016, an additional 70 MFIs’ licenses were revoked for their inability to meet requirements introduced as part of the central bank’s measures to sanitize the sector [27].

The same year, customer losses emanating from widespread MFI collapses provoked uproar from the public, compelling the President of Ghana to describe the industry situation as a crisis during his annual State of the Nation address. In 2018, Ghana’s central bank, the Bank of Ghana (BOG), conducted a financial performance audit that witnessed the categorization of over 347 microfinance companies as insolvent, with revocation of their licenses as a punitive measure. After the cleanup, 137 remained to receive clearance to operate [28].

Subsequently, BOG has introduced measures to deepen its oversight responsibility toward microfinance operators to avoid recurring challenges. These include mandatory onsite and remote quarterly and annual financial performance management appraisals. Although it is obligatory by law for microfinance practitioners to conduct financial performance management periodically, there is no formal regulation to enforce or motivate social performance measurement to ascertain if MFIs live up to their core mandate of serving the poor and reducing poverty.

As discussed earlier, financial performance evaluation is institutionalized in microfinance [17], while measuring social performance (poverty and outreach) remains an afterthought. Considering the number of subsidies, tax holidays, and exemptions enjoyed by MFIs, it is imperative to ascertain if the activities of MFIs in Ghana are in line with the social mission. Therefore, this study examines the impact of microfinance on the social performance of local households in the Kassena Nankana East District of Ghana. In addition, we used the micro-survey data of the 341 client households in this region to measure the social performance impact on service users. According to the Ghana Living Standards Survey report, the three northern regions (Northern, Upper East, and Upper West) recorded the highest poverty incidence in Ghana. The report documented a high poverty rate among all the districts in the Upper East region: Builsa South District Bawku West, Bongo, and Kassena Nankana [29]. The selection of the area was based on factors such as the existence of poverty, the use of microfinance as a poverty intervention, and the presence of vibrant microfinance organizations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Social Performance Call

The increasing demand for social responsibility studies can be attributed to the success and expansion witnessed in businesses [30] such as microfinance. When companies expand and become profitable, the need to invest a portion of the profits back into the people and their communities has become a standard business practice. Nor is it a secret that microfinance expansions are motivated by commercial entities that identified microfinance as an emerging market with a considerable profit potential [31]. Moreover, the powerhouse behind the market expansion propagates the institutionalization of financial performance management to track their investments and profit margins, leading to a widely recognized standard set of indicators and common reporting tools [32]. The net effect is the sidelining of social goals or social impact assessments, driving increased demand for the establishment of social performance tools and methods to foster a trade-off on the performance management front [4,15,16].

Regardless of the effort to introduce social performance management assessments, they still face inadequate robust, concise, and regular assessment mechanisms. For example, Palwak and Matul [33] and Mosley and Rock [34] argue that these challenges exist because social indicators are complex and challenging to conceptualize, and indecision affects the means and methods applied. Additionally, social outcomes are not always quantifiable. Therefore, they become difficult to measure since it is almost impossible to establish a causal link between treatment and changes [17]. Again, however, as social impact studies are expensive, complex, and time-consuming, they discourage profit-making organizations from investing time and money in conducting such studies [9,17]. A critical concern that continues to resonate in the impact assessment literature is the availability of reliable data and methodologies. In that regard, Zeller and Meyer [8] (p. 373) simply state that the unavailablility of reliable data and methods raises doubts about the industry’s poverty reduction prowess, thus affecting its outlook.

Despite the challenges above, the literature also points to multiple benefits of the social performance assessments of industry players, policymakers, and clients. First, social performance measurements can provide vital information on the risks and benefits of management systems and their products and services [35]. Data derived can help MFI management optimize their available resources and improve relationships with socially oriented investors and donors. The expected outcomes will bring enhanced benefits to clients and accountability to stakeholders [36], leading to increased and more timely deliveries of subsidies and donor funds critical to MFIs’ sustainability.

According to Copestake [4], the theory that underlines social performance is deeply rooted in the dual objectives of microfinance, that is, becoming a financially sustainable institution and remaining a force for social development [7,9,31]. Therefore, any attempt to sideline the social mission affects socially responsible investors and governments and their relationship with MFIs. We share similar sentiments with Zeller and Meyer [8] (p. 376) that uncertainty surrounding the poverty reduction capacity of microfinance prevents many states from providing friendly regulations and causes them not to use their scarce resources to support MFIs. The obvious way out is to measure the social performance of microfinance to provide evidence of its social development drive.

2.2. Empirical Evidence

Despite the introduction of robust methodologies, the outcome of impact studies remains inconsistent, spawning considerable interest among scholars and stakeholders. The conflicting results of many studies have triggered a divided school of thought among proponents of microfinance who say it positively impacts its beneficiaries [37,38,39,40,41,42], those who hold the opposing view that microfinance does not have a positive impact on poverty [43,44,45,46,47], and partial success converters [48,49]. However, literary contradictions and inconsistency in the microfinance impact literature remain a cause for worry.

Beginning with evidence for partial success, Nadar [50] utilized the correlation and regression method to examine the socio-economic well-being of 100 women in Cairo, Egypt, using assets, health, children’s education, and harmony in the family as indices. Whereas income and assets proved significantly positive, children’s education and harmony were significantly negative. A similar empirical review on socio-economic well-being by Al-Shami et al. [51] also produced a partial outcome. The results of the propensity score matching showed a significant positive effect on household income and accumulated assets, whereas female household decisions and mobility had a significant negative impact. A systematic review of evidence from sub-Saharan Africa by [52] indicated that though access to microfinance enables poor people to withstand shock, others become poorer because borrowers use the loans for consumption instead of productive investment. Re-enforcing borrowers’ remaining poor arguments, similar evidence from Bangladesh in South Asia also found a positive impact on participants’ overall well-being. However, the empirical results also proved that members of microfinance programs were poorer than non-members [53].

Regarding the positive effects of microfinance, Mahmood et al. [54] adopted the sample t-test and regression analysis to examine microfinance’s welfare impact on pre- and post-borrowers’ households in Pakistan. The results positively affected assets, income, expenditures on food, education, and health. In a related study in India, Bansol and Singh [55] proved that microfinance develops entrepreneurial skills and supports borrowers’ households. Similarly, the findings of a multinomial logistic regression conducted on borrowers of Aims microfinance in Malaysia revealed a positive effect on the poverty household income of woman participants. In Africa, a cross-sectional survey of 185 borrowers and 209 non-borrowers in rural Côte d’Ivoire was tested with propensity score matching and concluded that the borrower’s group has higher income on average than the non-borrowers [56]. The study further identified access to credit with women’s decision-making power in borrowers’ households. Finally, Nadege [57] used national household data from Cameroonians to investigate the relationship between microfinance and household well-being. The findings identified a significantly positive correlation between poverty and education. Finally, recent impact studies conducted in Ghana produced favorable results on poverty reduction [58,59,60,61].

On the contrary, one of the earlier impact studies that challenged microfinance positive impact studies was by Coleman [62] in Southern Thailand—using participants in village bank microfinancing as the treated group and designated villages that have not yet received credit as the controlled group. The study challenged the existing impact as dubious after the findings showed no significance for any asset and income of the members of the participating villages. The study further concluded that the small size of the loan may have influenced beneficiaries to divert the funds for consumption. Similar findings uncovered the diversion of loans for consumption instead of productive activities by Kotir and Obeng-Odoom [43]. The researchers concluded that microfinance had a modest impact on households because beneficiaries diverted a significant portion of the loans to consumers. For example, in a related study in Vietnam, Nghiem [63] examined the effect of microfinance on 470 households across 25 villages utilizing a quasi-experimental survey approach to limit selection bias. Finally, the results showed adverse effects on welfare indicators such as income and consumption.

3. Theoretical Framework

The underlying premise of social performance is the Theory of Change (TOC), with features and elements consistent with the definition of social performance: “Transmission of mission into practice.” TOC is known as a “pathway of change.” Similarly, the standard framework of the Social Performance Task Force, an association of global non-profit organizations that spearhead the advancement of microfinance social performance, describes the evaluation process as a pathway that begins with an analysis of the institution’s intent, designs, systems, and strategies, to produce an output (outreach and appropriate products and services) and outcome or change [5,15,16]. The pathway of the social performance common framework [16] is designed with a qualitative underpinning, hence the conclusions of Copestake [4] and Goldberg [30] that the common pathway for measuring social performance is based on a qualitative approach. Because social outcomes are not always quantifiable [17], it remains challenging to identify the causal linkage between the output and change indicators. The output indicators are the main variables that cause change. Therefore, it is crucial to quantify the output indicators to measure change correctly. Nonetheless, with the standard framework, both the outreach and the financial product and services that seek to have a direct causal effect on change are treated as outputs, supporting Maitroit’s [17] argument that causal linkages between treatment and change are difficult to determine.

As discussed earlier, TOC is the basis of the common social performance framework. Connell and Kubisch [64] assert that conducting TOC analysis with straightforward, collective, and collaborative processes creates unnecessary difficulties. Hence, the steps must identify long-term outcomes that a program or intervention seeks to achieve [65]. Moreover, Funnel and Rogers [66] conclude that TOC is a creation of logical models with underlying hypotheses that influence causal linkages expected to program impact. Considering the arguments mentioned and earlier expounded by the authors, one would expect the common framework that guides the management of the existing social performance regime to have logical models with clear indicators to identify the links between variables. However, we believe the framework’s qualitative background makes it difficult to establish relationships (between independent and dependent variables) and their causal effects.

The researchers adopted the social performance common framework and re-enforced TOC as its theory based on the literature discussed. However, we differ on utilizing outreach and products as output indicators. This paper proposes an adjustment to the social performance common framework by conceptualizing it as one that treats outreach and products and services as part of the institutional process, with a change in customer lives as the only output or result. Thus, we treat outreach and financial products and services as independent variables that may directly correlate with dependent variables.

Again, programs and interventions commonly referred to as products and services in commercial microfinance feature prominently in the TOC literature. In fact, Jackson [67] emphasized that TOC is sometimes referred to as Program Theory, originating from program evaluations. Despite emphasizing the importance of programs, interventions, or products and services, the social performance management framework fails to establish products’ relevance in the change process. We believe microfinance programs or products should be more prominent in social performance evaluations because microfinance depends on the client and institutional interactions. Financial products and services, along with programs, permit that coordination. Unfortunately, performance management tools such as the social performance common framework fail to capture the customer’s experience with products and services or the critical role of testing outcomes [37]. It is treated as an outcome like outreach, but our paper’s conceptual framework utilizes financial and nonfinancial products and services as independent variables. In sequence, the performance pathway begins with the institutional intent and designs, internal systems, output, outcomes, and change. Nonetheless, this study’s primary focus is output and change.

4. Microfinance in Ghana

The concept of microfinance is not new in Ghana. Traditionally, Ghanaians have engaged in savings and taking small loans from individuals and groups to establish or expand their small businesses. History has it that the Canadian Catholic Missionaries found the first credit union in northern Ghana in 1955. The purpose was to provide small credit to support farming activities. Again, in the 1990s, Susu (a small group or individual saving system) was a widespread practice in Ghana.

The development of formal microfinance in Ghana has undergone several phases, starting with the idea of subsidized government credit to the needy in 1950. The second phase was the introduction of microcredit by NGOs in the 1960s and 1970s. Again, the shift from a restricted financial sector regime to a liberalized system in 1986, coupled with the promulgation of PNDC Law 328 in 1991, ushered private investment into Ghana’s financial system [68]. The population and housing census undertaken by the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) in the year 2000 also identified financial gaps between the informal sector and financial services as a critical constraint on the economy. The census results showed that 80% of the working population emanates from the informal sector and lacks credit.

As lack of financial opportunities became a primary constraint to development in the informal sector, microfinance was formally introduced into Ghana’s financial industry in 2005. A committee of experts enacted a microfinance policy to encourage private sector participation. The policy led to the emergence of three categories of microfinance: (a) formal suppliers such as savings and loans companies, rural and community banks, and some development and commercial banks; (b) semi-formal suppliers such as credit unions, financial non-government organizations, and cooperatives; (c) informal suppliers including Susu collectors, rotate and accumulate savings and credit associations (ROSCA and ASCA), traders, money lenders, and individuals [69,70].

Over the years, the MFI sector has gone through several stages and reforms. First, the present regulatory document is guided by the microfinance policy of 2011. This policy created four categories: Tier 1 comprises all microfinance activities undertaken by Rural and Community Banks, Finance Houses, and Savings and Loans LLCs. The deposit-taking organizations are regulated under the Ghana Banking Act, 2004 (Act 673). Tier 2 involves deposit-taking and profit-making activities, Susu companies, and other non-deposit-taking financial services such as financial NGOs. These companies are regulated under companies limited by shares. Credit unions fall under this rubric; their regulations come under the Non-banking Financial Institutions Act 2008 (Act 744) [71]. Tier 3 includes money lenders and non-deposit taking financial NGOs, and Tier 4 is currently unregulated. All these organizations are guided by minimum capital requirements and permissible activities criteria which distinguish, in particular, deposit- and non-deposit-taking organizations [68].

5. Methods and Data

5.1. Methods

According to El-Zoghbi and Martinez [72], assigning an intervention to a treatment and control group is one of the most effective methods for impact studies but is barely utilized. For a study that seeks to identify the causal effects of treatment on outcomes, it is necessary to adopt a matching method in the absence of a random assignment of treatment conditions. We employed the PSM method, one of the most efficient methods for examining treatment impacts. This study measures the effects of microfinance activities, specifically MFI outreach, access to mobile banks and training, and the social outcomes of client households following the use of PSM. In addition, we placed client households who received these three treatments in a treatment group and those who did not receive such treatments in a control group. The PSM method was used to match observations of households in the treatment group (households who have access to mobile banks, MFI outreach, and training) and those in the control group (households without access to those) by creating the conditions of an experiment where the treatment elements are randomly assigned.

We observed that due to limited resources, treatment intervention (mobile bank, MFI outreach, and training) was not allocated randomly across clients. For example, MFI training was for those who could afford it. Mobile banking was available, particularly at market centers and select remote areas with difficult access to the main branch. MFI outreach was designed specifically for very poor clients. Due to unobserved factors, specific household clients were granted access or decided to access the MFI. In this context, selection bias may arise because of the non-randomness of mobile banking access and the MFI’s outreach and training. Therefore, we employed the PSM method to reduce the selection bias and compared social performance outcomes for household clients between the treated and control groups. The primary purpose of the matching approach was to identify the counterfactual outcomes to enable the researchers to correct the selection biases created by the sampling method. The counterfactual outcomes represent the benefits derived from access to treatment, including household income, business expansion, decision making within households, political participation, women’s empowerment, social cohesion, and loan use.

We employed a standard formula for the Rosenbaum–Rubin model’s potential outcome approach. The ATT is specified as follows:

where Ti denotes a dummy variable indicating whether client households have access to mobile banking and the MFI’s outreach and training (Ti = 1), or they have no access to those services (Ti = 0); E(Yi(1)|Ti = 1) is the average of the outcome variables of client households who have access to the bank’s services. E(Yi(0)|Ti = 1) is the counterfactual, i.e., the average outcomes of the treatment group that would have prevailed in the absence of treatment. The ATT is obtained by the average difference in outcomes between treated households and their counterfactuals

The average outcome, E(Yi(1)|Ti = 1), is available, but the counterfactual, E(Yi(0)|Ti = 1), is not readily observable. However, the propensity score can be used to match households with treatment to households without treatment. Assuming P(Zi) is the propensity score, i.e., the likelihood that a household will be treated on the bases of its observable characteristics, and maintaining the assumptions of conditional independence (CIA) and overlap, ATT is expressed by:

where Zi denotes the covariates representing the household’s observable characteristics, the ATT is estimated by simplifying the mean difference in outcomes between treated households and similar households to those of the treatment group based on the propensity score. An essential element in the PSM is choosing a matching algorithm that can significantly eliminate bias and produce statistically equal covariate means between the two groups. We used Kernel matching and radius matching techniques.

5.2. Data

The principal investigator and field officers collected the data for this study from December 2020 to April 2021. According to [40], household clients with three years of exposure to a microfinance program or intervention are best for impact studies. Therefore, our focus was on household clients with 4–10 years of experience. When choosing an appropriate sample with a probability of equal opportunity for all, three factors are considered: the margin of error, the confidence level or alpha level, and the degree of variables. For example, in social science research, an alpha level of 0.05 or 0.01 with a 5% margin of error is acceptable. Therefore, the researchers adopted Yamane’s model to determine the study’s sample size.

A sample of 350 households from a total population of 2800 was obtained. However, 341 were used due to irregularities. The adopted MFIs were instrumental in providing us with the list of possible clients and group leaders within the focus year bracket. To maintain fair representation, we used all 15 areas with a microfinance presence. Self-selection joint liability groups based on shared attributes were the microfinance regime’s lending strategy for customers. Because group lending strategies bear similar characteristics with stratified random sampling techniques, adopting stratification was the most appropriate and efficient option considering the time and financial constraints. The selection process initially involved first utilizing the available groups. A random sample of a number proportionate to each stratum was taken with support from the group leaders and considering the focus years. Subsets of these strata were pooled again to construct a random sample. A survey questionnaire was the primary data collection instrument. The survey’s focus was to investigate the impact of mobile banking and the MFI’s outreach and training of the client households. Hence, the questions focused on extracting valid information for both the independent and dependent variables. Based on the location information provided by the MFIs with assistance from the group leaders and three research assistants recruited from the community, the questionnaires were administered to the sample population. Because of missing variables, we used 341 sample client households for the empirical analysis.

Table 1 reports the summary statistics of variables used in the study. The choice of variable is consistent with the key indicators of social performance management [15], including other variables to fit the study’s purpose. Our treatment variables included access to mobile banks, outreach activities, and training provided by MFI to clients. The variable of access to mobile banking represents the proximity of microfinance branches or offices to remote customers because it is a bank on a wheel. The outreach variable stands for providing financial services to the poor and excluded clients. Microfinance practices training is considered a nonfinancial service. Hence, many microfinance impact studies do not capture the significance of nonfinancial services. Therefore, the focus of this study is the utilization of nonfinancial products and services such as training. We observed that loans are the primary product for the MFI’s understudy in the study area. Therefore, utilizing loans as a variable may deliver a biased result.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of variables.

Therefore, we chose MFI training to represent the products and services variables. These treatment variables were constricted as binary variables. For example, whether households can access mobile banking denotes a dummy variable equal to 1—those without mobile banking access equal to 0. Outreach is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the household client is considered poor or very poor and lacks access to financial services and 0 if the household is not classified as poor and excluded. Likewise, training is a dummy variable equal to 1 if a household has received training provided by the MFI; otherwise, it is 0.

Regarding outcome variables for microfinance clients’ households, we used business expansion or new enterprises, improvements in household income, household decision making, loan use for consumption, loan use for production, loan delivery time, and wider developmental objectives that reflect millennium development goals such as women’s equality, community participation, transparency, social cohesion, political participation, and women’s empowerment. The aforementioned dependent variables are consistent with the standard social performance framework’s change indicators.

Transparency would be a dummy variable equal to 1 if an individual experienced transparency in the MFI’s dealings. High loan costs capture the perception of households that believe the loan price is high. A dummy variable of timely loan disbursement equals 1 if loans are disbursed from 1–2 weeks after the loan application. The variable of delayed loan disbursement equals 1 if loans are disbursed from 2 weeks on. Business expansion is a dummy variable that equals 1 if client households have expanded their farms or trade; business expansion equals 0 if there was no expansion. A dummy variable of income improvement measures the client’s experience of increased income, which equals 1. We use a dummy variable of political participation equal to 1 to examine the impact on household participation in political activities and 0 if there was no increase in political activities. A dummy variable of women’s empowerment equals 1 if female clients feel empowered after joining microfinance and 0 if otherwise. In a patriarchal locality, community participation may positively affect women’s well-being. Thus, we set community participation equal to 1 for women’s involvement in community activities and 0 if there was no improvement in women’s engagement in community activities. We use a dummy variable for household decision making if access to microfinance positively affects women’s contributions to household decision making. A dummy variable for social cohesion equals 1 if microfinance membership builds social cohesion; it equals 0 if otherwise. This study examines the impact of microfinance on the production and consumption behavior of households, equaling 1 for a positive impact and 0 for no observed effect. A dummy variable of loans used for production measures whether or not clients invested the loans for production or to support production activities and vice versa. Loan use for consumption captures customers utilizing loans for household consumption activities.

We use covariates to control the characteristics of client households. Age is a continuous variable indicating the age of the household head. Married is a dummy variable representing marital status. Number of children is a continuous variable indicating the number of children in each household. Farmer is a dummy variable indicating status as a farm household. Number of years is a continuous variable indicating the number of years as a member of an MFI. Distance is a dummy variable indicating the distance to the main microfinance branch. East region is a dummy variable of that region.

6. Empirical Results

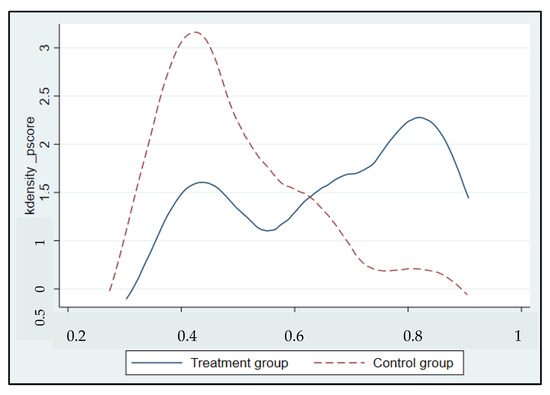

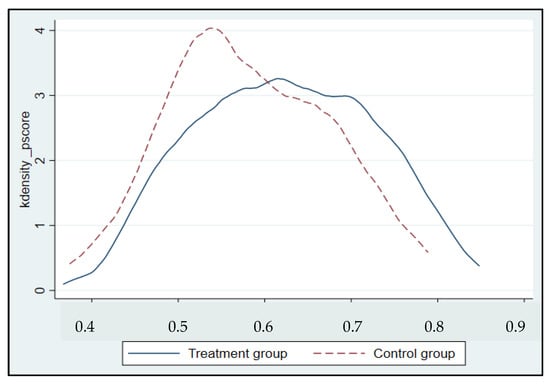

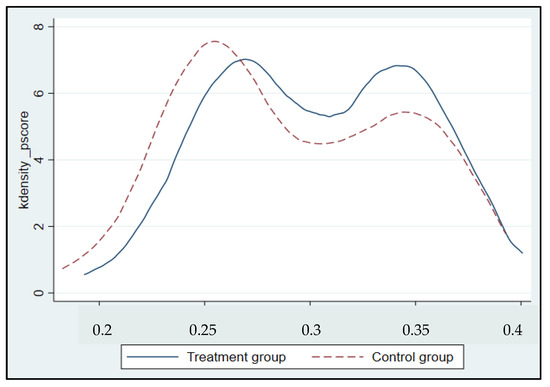

Table 2 reports the results of a probit estimation for the prediction of the propensity scores. Several covariates have a significant effect on access to microfinance. For example, households located in remote areas are more likely to access mobile banking. Similarly, the distance increases the probability of access to MFI outreach activities. Distance has a significant nonlinear impact on the probability of access to mobile banking and MFI outreach. Farm households are unlikely to receive MFI training. In matching, each household with access to microfinance is matched to a household without access but with a similar propensity score. We employed kernel and radius matching methods. The bandwidth of the kernel matching was set equal to 0.06 as a rule of thumb. As for radius matching, we used a caliper of 0.02. One observation was dropped because of off-support in the matching between households with access to mobile banking and those without. Likewise, we dropped 12.2 observations from the treated group for the matching of access to outreach or training, respectively. We summarized the distribution of propensity scores of the treated and control households after matching (Figure A1, Figure A2 and Figure A3 of Appendix A). The distribution of the treatment and control group households are mostly overlapped.

Table 2.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of probit models.

In Table A1, Table A2 and Table A3 of Appendix A, we report the balancing of test results on covariates of the matched sample. As expected, the covariates of distance, distance squared, and the dummy variable of farmers do not satisfy the balancing property before matching. Yet, the differences in the three covariates became insignificant after matching. In addition, the mean and median of absolute biases were reduced in both the radius and kernel matching. Pseudo R-squared values were substantially reduced because of matching. These results suggest that both matching methods were successful in balancing covariates, which indicates their validity and robustness.

Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 present estimated results of ATT adoption of access to microfinance on several outcomes of social performance. The standard errors for the PSM estimation were estimated using bootstrapping with 200 replications. To check the sensitivity to unobservables or hidden bias, we computed the Rosenbaum bounds’ critical levels of odds ratio (Γ) at the 10% level. The larger the value that the Rosenbaum bounds suggest, the less sensitive our estimated results are to hidden bias. In our estimations, some odd ratios are low, which implies their sensitivity to unobservables. Others reflect mostly large values, which imply the robustness of the treatment effects.

Table 3.

ATT of mobile bank.

Table 4.

ATT of M.F. bank’s outreach.

Table 5.

ATT of M.F. bank’s training.

The results show that access to microfinance significantly affects social performance. Access to mobile banking positively affects high loan costs and timely loan disbursement. In contrast, that access has a negative impact on delayed loan disbursement. Mobile banking also positively affects business expansion, if not income improvement. In addition, because mobile banking has created an environment that simplifies loan requirements, customers can quickly complete required loan documents. These negatively impact delayed loan disbursements. In addition, because mobile banking is a one-stop shop that effectively moves the MFI closer to the customer, it eliminates the difficulties associated with accessibility, branch visits, knowing your customer requirements, and other conditions that demand physical verification. Hence, mobile banking automatically impacts the time spent on service delivery. Finally, the costs associated with the timely delivery of services increase operational expenditures, affecting service costs. Hence, mobile banking appears to correlate with the high cost of loans. Mobile banking eradicates long distances, and the speedy delivery of services enhances productivity, which improves income. Because all the features of mobile banking point to the swift delivery of products and services, loan disbursement times are reduced.

The ATT estimates for MFI outreach suggest a significant impact on swift loan disbursement and delayed loan disbursement time. The positive and significant effects on timely loan disbursements are that the outreach strategy processes require the MFIs to adopt a more customer-friendly approach. This practice has eliminated some requirements, thus shortening the loan processing time.

The estimated ATT of the MFI’s training is statistically significant compared to political participation, women’s empowerment, household decisions, and community participation. The MFI’s training primarily provides information and instruction to individuals to enhance their knowledge and skills to efficiently perform specific tasks. Thus, the findings support that training provided by the MFIs was successful in their intentions and purposes by significantly affecting decision making in the household, empowering women clients, and positively changing political and community participation. In addition, MFI training encourages savings through reduced consumption and increased investment in production activities.

We estimated ATTs by using the PSM. Yet, the PSM method computed the probability to be a treated group based on observed characteristics. Following Oster [73], we tested the coefficient stability of the treatment effects, which produced statistically significant results in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. We used the STATA code psacalc to calculate δ and coefficient bands. Table 6 presents the results of the sensitivity test for selection on unobservables. The ratio of selection on unobservables to selection on observables, δ, captures how large the effect of unobservables needs to be in proportion to the effect of observables such that the treatment effect becomes 0, given a maximum value of R-squared. We calculated δ assuming Rmax =1.3 R-squared and β = 0. The identified value was calculated assuming Rmax = 1.3 R-squared with δ = 1. For instance, the value of δ is 1.381 in the impact of banks’ training on community participation, indicating that unobservables need to be at least 1.381 times stronger than observable covariates to drive the treatment effect to zero. All estimates are robust since δ is higher than 1. In addition, all the identified sets estimated do not include zero. The estimated coefficients are reasonably stable, and the selection on unobservables would have to be quite large to overturn our main results. These results suggest that the estimated coefficients of the treatment effect are robust to unobservable heterogeneity.

Table 6.

Selection on unobservable characteristics: test of coefficient stability.

The PSM method is enabled to control the observable characteristics between the treated and control groups of client households. In addition, we discussed that our estimation results are robust against unobservable effects by Oster’s coeffeicient stability test. However, the selection bias may remain since the decision to be a treated group depends on the choice of individual households. Unobservable characerisitics such as motivation to reach microfinance may affect both treated and outcome variables. Following Heckman [74] and Heckman et al. [75], we estimated Heckman’s two-step sample selection model. Table A4 of Appendix A presents first stage probit model estimators, using binary variables (access to mobile banks, outreach, banks’ training) as dependent variables and a set of exogenous variables determining treatment. Based on the estimated parameters of the 1st stage selection equation, we computed the inverse Mills ratio to be included in the 2nd stage equation. The inverse Mills ratio can capture the possible selection bias and omitted variables, or other unexplained parts in the error term. To investigate the problem of selection bias, we employed Heckman’s sample selection approach, which found significant results in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. Table A5, Table A6, Table A7, Table A8 and Table A9 of Appendix A report the estimated results of the 2nd stage equation. While the inverse Mills ratio is statistically significant at the 10% level in the equation of the impact of mobile banks on business expansion and income improvement as well as that of the impact of training on loan use production (Table A6 and Table A9), the inverse Mills ratios are mostly found to be statistically insignificant. These results do not suggest the sample of treated households suffer from serious selection bias. Together with the PSM results, we reserve the significant impact of mobile banks on business expansion and income improvement, and that of training on loan use production, but other significant estimates of ATTs can be considered robust against the selection bias.

7. Discussion

The estimation results for outreach positively affect timely loan disbursements but have a negative effect on delayed loan disbursement times. MFIs with deliberate poverty outreach strategies adopt such customer-friendly approaches. The idea is to present a poverty-friendly outlook and implement practices that fit the poor clients’ socio-economic environment. Customer-friendly operational strategies include recruiting staff from the locality, unbiased selections, waiving complicated requirements, non-collateral, simple loan application forms, and timely loan disbursement. We observed that the MFIs operating in the area under study recruited staff from the local communities who spoke the local language and were familiar with the people and their characteristics. Therefore, the team waived some documentary requirements, such as national identification cards and utility bills. Because the MFIs engage in relatively unrestricted social collateral, the challenges of selectivity, documentation, and collateral requirements diminish. These have translated into the outreach having a significant effect on timely loan disbursements, as documented by this study. Like Norjo and Adjasi [18], easy access leads to the efficient application of the loans increasing productivity and income with an overall effect on poverty. Our findings on outreach are consistent with Ennim [18]: outreach affects poverty positively.

Conversely, when poor clients strictly follow the required loan documentation submissions, just as well-to-do clients and MFIs adhere to all loan regulations, loan delivery times will undoubtedly be extended. For example, many communities lack water or electricity and do not have utility bills to prove personal information requirements; strict requirements may prevent or delay loan delivery times. These provide insights into why the study’s findings negatively identified outreach and delayed loan payment times.

The empirical findings suggest that mobile banking positively affects high loan cost, timely loan disbursement, business expansion, and income, but we obtained a negative correlation between mobile banking and delayed loan disbursement. Access to microfinance offices is a massive challenge for poor people in remote locations. However, if the critical objective of microfinance is poverty reduction, then it is essential to implement policies that will eliminate impediments to household access. Therefore, it is not surprising that the proximity of microfinance branches is considered a measuring indicator for the breadth of outreach [76,77]. Moreover, because many MFIs serve customers residing in dispersed and remote locations, it is financially and practically impossible to provide branches closer to all customers. In such situations, Zeller and Meyer [8] (p. 6) posit that it is essential to introduce innovative mechanisms that can promote outreach to the poor.

Like Dary and Issahaku [78], we observed that the MFIs in the study area deploy a wide range of innovative strategies such as mobile banking vans, motorbikes for field officers, and mobile money loans disbursement. The introduction of mobile banking vans specifically has moved banking services closer to the people, broadening accessibility and the rapid delivery of loans to the beneficiaries. Innovations significantly impact productivity [20,21], influencing mobile banking to positively affect timely loan disbursements.

The positive effect of mobile banking and timely loan disbursement is absolute in that the loan processes involve filling out application forms, conducting KYC requirements, visiting customers to confirm their residence, personal identification document verifications, and most importantly, credit-worthy analysis. These loan processes adopted by MFIs in Kassena Nankana East are similar to Yeboah [40] and Salia [79] in that unconventional methods are the primary credit analysis tools used for the poor. These include prior knowledge of the customer’s residence, family credit history, farm or work visits, a customer history of hard work, and others. Because the operational characteristics of mobile banking involve moving to customer locations, conducting these requirements becomes more straightforward and simplified, which shortens the loan processing time, leading to rapid loan disbursement.

The common paradigm posits that serving the poor is expensive, and the delivery of customized services such as mobile banks imposes an additional cost on the enterprise. For example, transactional and administrative expenses influence the cost of lending. Since high transactional costs affect MFIs’ self-sufficiency and sustainability. MFIs need to charge fees sufficient to cover the expenses incurred for remote services: transport, ICT, and more excellent internal controls [7]. In addition, because loan charges are calculated based on the cost structure of Ledgerwood [80] (p.139), it is not uncommon that this study identified a positive correlation between mobile banking and high loan costs. This finding corresponds with Pedroso and Do [81], that distance affects the cost of loans.

Conversely, the findings of this study showed that mobile banking is not significant in relation to increased income. These findings are inconsistent with Kotir and Odoom [43] and Peprah et al. [24], who found that access to credit improves the production capacity and increases beneficiaries’ household incomes.

Similarly, mobile banking did not influence business expansion. The findings of this section also differ from Barnes et al. [82], who identified easy access to credit as positively influencing the expansion of new businesses, the introduction of new products and services, new market entries, and reduced costs by engaging in bulk purchasing.

In addition, our findings showed that mobile banking negatively correlates with delayed loan disbursements. Ordinarily, customers are required to visit the branch for the loan subscription activities, involving filling out loan application forms and other submissions. Because of a lack of reliable data on poor people, information about microfinance clients is determined solely from details declared by the applicant. Therefore, loan officers must verify them to avoid adverse selections [81] and unpaid loans. Because information verification is conducted manually, the process may take several weeks or months, especially in remote and dispersed settlements with many applicants. This creates a keen effect on loan delivery time. Nonetheless, mobile banking has sped up the process.

Similar to Haider et al. [22] and Huis et al. [83], training was statistically significant for political participation, women’s empowerment, household decision making, and community participation. Regarding the impact of training on the use of loans, the value of utilizing loans for consumption and loans used for production were negative. The positive relationship between training and many social variables is a positive poverty reduction indicator.

Though this study has identified training as having positive relations with many social indicators, except for the use of loans for production, the general understanding from customer engagement was that training is primarily conducted at the initial loan disbursement. All other training is per the request of a group, which comes at a cost to members unless it is related to a health outbreak. Despite limited training, we assume that it positively impacted the social indicators for several reasons. First, training may affect microfinance clients regardless of the number of times it is conducted. Secondly, the positive outcomes may be a by-product of the group lending approach, which has translated into social cohesion, collective agreement, and cooperation among the service users. We share similar sentiments with Putman [84] that the promotion of collaboration leads to the accumulation of social capital, which may have influenced the positive change in social indicators among the microfinance beneficiaries. Second, we observed that social capital has transformed into various vertical women’s social groups such as Ansarul Islam, Wejegedam, Nurul Islam, the Big Six, and Nassara women’s groups. These groups formed out of existing microfinance joint liability groups collaborating with some NGOs, who occasionally organized enterprise and social training for their members. Finally, for a patriarchal community, the appointment of a woman as a political head (Regional Minister) may have also contributed to the transformation and empowerment of women’s political and social participation in the community.

8. Conclusions

Improving the lives of the poor is the primary social goal of microfinance. In this regard, MFIs must develop and implement programs, products, and services tailored to reduce poverty and create wider social benefits for their clients. Conducting impact studies is the surest way to measure the effectiveness of microfinance in the fight against poverty. Nonetheless, concerns over the neglect of social impact studies have garnered heated debate. Therefore, this study attempts to measure the impact of the microfinance social performance on beneficiaries. The primary objective is to estimate the average treatment effect of outreach and product and services on the lives of service users. Unlike the existing framework that treats outreach and appropriate products and services as outputs, we adopted PSM to utilize outreach products and services as treated variables, with changes in customers’ lives as the primary output or result.

Our results support hypothesis 1: that outreach strategies positively impact poverty indicators. These findings confirm Annim [18], who found that outreach that extends credit access to the rural poor reduces poverty. Our results are consistent with the theory that access to microfinance credits improves beneficiaries’ social life and welfare [26,43]. Hypothesis 2’s findings also validate Nyeadi [20] and Fu et al. [21], who found that innovations in microfinance are vital in the fight against poverty. The findings of hypothesis 3 validate Haider et al. [22] and Hrader [23], finding that training provisions for microfinance clients positively affects poverty. Lensink et al. [85] also confirm our hypothesis 3, that when microfinance institutions provide social services such as training, this improves the proper use of loans. Finally, considering that training was significant to most of the study’s social indicators, the study’s finding fall in line with the argument espoused by Peprah et al. [24], that credit accompaniments such as training is vital to poverty reduction strategies.

The paper’s findings contribute to the limited body of literature on the impact of outreach and products and services on changes in the lives of service-users in microfinance social performance management. Additionally, this paper’s contribution proves that nonfinancial services are equally crucial to delivering change for microfinance beneficiaries. Training has proven essential for the efficient utilization of loans and the delivery of social benefits, differing from the current practice where MFIs disregard training and other social services as nonessential financial services that only increase transactional costs.

While trying to investigate the problems of selection bias, we utilized PSM, Oster’s coefficient stability, and Heckman’s two-step sample selection. We found a significant impact of mobile banking on business expansion and income improvement. We also found a significant impact of training on the use of loans for production for both PSM and Oster. However, the Heckman model’s results were reserved. Therefore we cannot deny the possibility of selection bias by Heckman’s sample selection model. We agree that the study has some limitations. Nonetheless, the results typically apply to all microfinance practitioners, governments, socially-oriented investors, and donors who want to pursue accountability and value for money audits. Finally, all practitioners can use our framework and methodology to evaluate the impact of management decisions and internal processes on the lives of service users.

The critical policy implications are that access to microfinance credit autonomously reduces poverty. However, added services stimulate the most significant effect. Mobile banking as an outreach strategy also provides a solid background for policymakers struggling to solve the problem of outreach to the rural and remote poor. If the purpose of microfinance is to fight poverty, access to credit for the poor remains essential. Hence, policymakers must introduce strategies that incorporate innovative additional services such as mobile banking and training as bundle packages with credit. The output indicators of the social performance management standard framework are determined by the organization’s management intent and internal processes. Therefore, for future studies, it is recommended that a quantitative approach be adopted to measure the microfinance institutions’ internal processes and their effect on outreach and products and services. This approach will help in evaluating institutional-level social performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O. and K.K.; methodology, K.K.; formal analysis, E.O. and K.K.; investigation, E.O.; resources, E.O.; writing—original draft preparation, E.O.; writing—review and editing, E.O. and K.K.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, E.O.; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the research grant “Strategic Initiative S” provided by the University of Tsukuba.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsink, however approval was not required because the survey was conducted during the height of the COVID 19 pandemic and following the WHO recommendations it was critical to avoid physical contacts. The strategy was to avoid all direct contact including group discussion and interviews with subjects. The data was recorded such that the subjects could not be identied by the researcher who lived abroad.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects who participated in the survey.The ethical statement was written and sometimes read to respondents. Subjects were dully informed of their confidentiality and rights before participating in the exercise. Subjects were further informed not to mention their names or add any clue that may reveal their identitities, thus their participatory were voluntary. They had the right to withdraw form the process without been disadvantaged in any way and may proceed only if they agree. No data was obtained from persons under 16 yeaars.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available at the International Public Policy department of the University of Tsukuba. Regarding data submission requests, contact eofori7@gmail.com.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the management of Fast link Microfinance Ltd. and MASLOC for their support throughout the data collection and interview process. A very big thank you to Kenichi Kashiwagi for his supervision, support, encouragement, and contribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Balancing test of matched sample: mobile bank.

Table A1.

Balancing test of matched sample: mobile bank.

| Variable | Unmatched Samples | Kernel Matching | Radius Matching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Diff: p > |t| | Mean | Diff: p > |t| | Mean | Diff: p > |t| | ||||

| Treated | Control | Treated | Control | Treated | Control | ||||

| Age | 39.61 | 39.45 | 0.851 | 39.56 | 38.90 | 0.378 | 39.56 | 39.03 | 0.476 |

| Married | 0.884 | 0.844 | 0.299 | 0.883 | 0.870 | 0.702 | 0.883 | 0.876 | 0.832 |

| Number children | 2.981 | 3.126 | 0.392 | 2.995 | 3.132 | 0.362 | 2.995 | 3.035 | 0.793 |

| Farmers | 0.529 | 0.496 | 0.554 | 0.532 | 0.601 | 0.160 | 0.532 | 0.632 | 0.040 |

| Years membership | 5.782 | 5.800 | 0.900 | 5.785 | 5.673 | 0.371 | 5.785 | 5.650 | 0.275 |

| Distance | 9.642 | 4.790 | 0.000 | 9.606 | 9.579 | 0.972 | 9.606 | 9.852 | 0.759 |

| Distance squared | 155.13 | 59.92 | 0.000 | 154.48 | 160.52 | 0.772 | 154.48 | 165.64 | 0.592 |

| East region | 0.680 | 0.756 | 0.132 | 0.678 | 0.715 | 0.420 | 0.678 | 0.672 | 0.904 |

Note: Treated are households who have access to mobile bank.

Table A2.

Balancing test of matched sample: bank’s outreach.

Table A2.

Balancing test of matched sample: bank’s outreach.

| Variable | Unmatched Samples | Kernel Matching | Radius Matching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Diff: p > |t| | Mean | Diff: p > |t| | Mean | Diff: p > |t| | ||||

| Treated | Control | Treated | Control | Treated | Control | ||||

| Age | 39.95 | 38.93 | 0.227 | 39.49 | 39.71 | 0.777 | 39.49 | 39.52 | 0.968 |

| Married | 0.860 | 0.881 | 0.583 | 0.867 | 0.873 | 0.846 | 0.867 | 0.872 | 0.874 |

| Number children | 2.952 | 3.172 | 0.195 | 3.005 | 3.080 | 0.620 | 3.005 | 3.051 | 0.766 |

| Farmers | 0.527 | 0.500 | 0.633 | 0.513 | 0.516 | 0.955 | 0.513 | 0.536 | 0.651 |

| Years membership | 5.783 | 5.799 | 0.914 | 5.780 | 5.784 | 0.975 | 5.780 | 5.798 | 0.887 |

| Distance | 8.606 | 6.354 | 0.007 | 8.086 | 7.466 | 0.417 | 8.086 | 8.253 | 0.832 |

| Distance squared | 134.61 | 90.91 | 0.038 | 122.92 | 111.37 | 0.548 | 122.92 | 129.11 | 0.753 |

| East region | 0.700 | 0.724 | 0.643 | 0.697 | 0.721 | 0.616 | 0.697 | 0.706 | 0.851 |

Note: Treated are households who have access to bank’s outreach.

Table A3.

Balancing test of matched sample: bank’s training.

Table A3.

Balancing test of matched sample: bank’s training.

| Variable | Unmatched Samples | Kernel Matching | Radius Matching | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Diff: p > |t| | Mean | Diff: p > |t| | Mean | Diff: p > |t| | ||||

| Treated | Control | Treated | Control | Treated | Control | ||||

| Age | 39.92 | 39.39 | 0.560 | 39.83 | 39.50 | 0.760 | 39.83 | 39.81 | 0.987 |

| Married | 0.891 | 0.858 | 0.416 | 0.889 | 0.885 | 0.925 | 0.889 | 0.902 | 0.756 |

| Number children | 3.000 | 3.054 | 0.766 | 2.980 | 3.062 | 0.701 | 2.980 | 3.034 | 0.799 |

| Farmers | 0.446 | 0.546 | 0.091 | 0.455 | 0.514 | 0.404 | 0.455 | 0.470 | 0.826 |

| Years membership | 5.802 | 5.783 | 0.906 | 5.788 | 5.795 | 0.970 | 5.788 | 5.810 | 0.909 |

| Distance | 7.841 | 7.671 | 0.851 | 7.383 | 7.740 | 0.734 | 7.383 | 7.719 | 0.750 |

| Distance squared | 120.73 | 116.05 | 0.836 | 104.38 | 118.34 | 0.577 | 104.38 | 118.83 | 0.566 |

| East region | 0.693 | 0.717 | 0.662 | 0.707 | 0.709 | 0.970 | 0.707 | 0.711 | 0.958 |

Note: Treated are households who received bank.

Table A4.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of probit model of 1st stage sample selection equation.

Table A4.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of probit model of 1st stage sample selection equation.

| Mobile Banking | Outreach | Training | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | Robust SE | Coefficient | Robust SE | Coefficient | Robust SE | |

| Constant | −0.566 | 0.546 | −0.324 | 0.524 | −0.656 | 0.528 |

| Age | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.009 |

| Married | 0.204 | 0.218 | −0.132 | 0.207 | 0.165 | 0.224 |

| Number of children | −0.066 | 0.048 | −0.070 | 0.047 | −0.024 | 0.047 |

| Farmers | 0.091 | 0.145 | 0.067 | 0.141 | −0.241 * | 0.145 |

| Years of membership | −0.019 | 0.054 | −0.005 | 0.053 | 0.007 | 0.055 |

| Distance | 0.155 *** | 0.031 | 0.075 | 0.031 | −0.005 | 0.031 |

| Distance squared | −0.004 *** | 0.001 | −0.002 ** | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| East region | 0.106 | 0.170 | 0.082 * | 0.164 | −0.092 | 0.169 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.106 | 0.032 | 0.010 | |||

| Observations | 341 | 341 | 341 | |||

Note: *, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Table A5.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of 2nd stage equation..

Table A5.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of 2nd stage equation..

| Selection of Mobile Banking | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Loan Cost | Timely Loan Disbursement | Delayed Loan Disbursement | ||||

| Coefficient | Robust SE | Coefficient | Robust SE | Coefficient | Robust SE | |

| Constant | 0.586 ** | 0.251 | −0.006 | 0.256 | 0.463 | 0.282 |

| Age | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.004 | −0.006 | 0.005 |

| Married | −0.052 | 0.090 | −0.010 | 0.105 | 0.144 | 0.112 |

| Number of children | 0.039 ** | 0.020 | −0.008 | 0.020 | 0.012 | 0.024 |

| Farmers | 0.070 | 0.057 | 0.126 ** | 0.061 | −0.169 ** | 0.069 |

| Years of membership | 0.008 | 0.020 | 0.029 | 0.025 | 0.022 | 0.028 |

| Inverse Mills ratio | 0.088 | 0.112 | 0.140 | 0.124 | 0.114 | 0.133 |

| R2 | 0.036 | 0.035 | 0.050 | |||

| Observations | 206 | 206 | 206 | |||

Note: ** indicates significance at the 5% level.

Table A6.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of 2nd stage equation.

Table A6.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of 2nd stage equation.

| Selection of Mobile Banking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business Expansion | Income Improvement | |||

| Coefficient | Robust SE | Coefficient | Robust SE | |

| Constant | 0.603 ** | 0.270 | 0.556 ** | 0.236 |

| Age | −0.006 | 0.004 | −0.004 | 0.004 |

| Married | −0.046 | 0.103 | 0.162 | 0.102 |

| Number of children | 0.050 ** | 0.022 | 0.036 * | 0.019 |

| Farmers | 0.013 | 0.066 | 0.063 | 0.057 |

| Years of membership | 0.010 | 0.026 | −0.001 | 0.023 |

| Inverse Mills ratio | 0.207 * | 0.125 | 0.189 * | 0.109 |

| R2 | 0.054 | 0.059 | ||

| Observations | 206 | 206 | ||

Note: * and ** indicate significance at the 10% and 5% levels, respectively.

Table A7.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of 2nd stage equation.

Table A7.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of 2nd stage equation.

| Selection of Outreach | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timely Loan Disbursements | Delay Loan Disbursements | |||

| Coefficient | Robust SE | Coefficient | Robust SE | |

| Constant | −0.213 | 0.319 | 0.462 | 0.339 |

| Age | 0.005 | 0.005 | −0.004 | 0.005 |

| Married | 0.000 | 0.094 | 0.116 | 0.105 |

| Number of children | 0.002 | 0.022 | −0.022 | 0.026 |

| Farmers | 0.099 | 0.062 | −0.109 | 0.070 |

| Years of membership | 0.010 | 0.026 | 0.038 | 0.028 |

| Inverse Mills ratio | 0.270 | 0.257 | 0.006 | 0.275 |

| R2 | 0.022 | 0.036 | ||

| Observations | 207 | 207 | ||

Table A8.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of 2nd stage equation.

Table A8.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of 2nd stage equation.

| Selection of Training | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political Participation | Women Empowerment | Household Decision | ||||

| Coefficient | Robust SE | Coefficient | Robust SE | Coefficient | Robust SE | |

| Constant | −1.943 | 2.026 | 0.413 | 1.601 | 0.322 | 2.209 |

| Age | 0.024 *** | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.006 | −0.014 | 0.009 |

| Married | 0.093 | 0.227 | 0.047 | 0.215 | 0.451 * | 0.239 |

| Number of children | 0.011 | 0.041 | 0.023 | 0.032 | −0.021 | 0.043 |

| Farmers | −0.100 | 0.273 | 0.030 | 0.215 | −0.265 | 0.296 |

| Years of membership | −0.005 | 0.038 | 0.031 | 0.030 | −0.027 | 0.041 |

| Inverse Mills ratio | 1.243 | 1.490 | 0.058 | 1.256 | 0.571 | 1.636 |

| R2 | 0.122 | 0.031 | 0.129 | |||

| Observations | 101 | 101 | 101 | |||

Note: * and *** indicate significance at the 10% and 1% levels, respectively.

Table A9.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of 2nd stage equation.

Table A9.

Estimated coefficient and robust standard errors of 2nd stage equation.

| Selection of Training | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Participation | Loan Use Production | Loan Use Consumption | ||||

| Coefficient | Robust SE | Coefficient | Robust SE | Coefficient | Robust SE | |

| Constant | 2.035 | 2.018 | −2.149 | 1.599 | 0.635 | 0.755 |

| Age | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.005 | −0.001 | 0.002 |

| Married | −0.115 | 0.215 | 0.307 * | 0.163 | −0.007 | 0.059 |

| Number of children | −0.011 | 0.040 | −0.025 | 0.031 | −0.003 | 0.022 |

| Farmers | 0.230 | 0.260 | −0.344 | 0.223 | 0.064 | 0.123 |

| Years of membership | −0.020 | 0.036 | 0.022 | 0.025 | −0.029 | 0.023 |

| Inverse Mills ratio | −1.160 | 1.545 | 2.291 * | 1.227 | −0.362 | 0.544 |

| R2 | 0.044 | 0.097 | 0.083 | |||

| Observations | 101 | 101 | 101 | |||

Note: * indicates significance at the 10% level.

Figure A1.

Distribution of propensity scores between treatment and control groups after matching: mobile bank. Note: The treatment group are households which have access to mobile banks.

Figure A2.

Distribution of propensity scores between treatment and control groups after matching: banks’ outreach. Note: The treatment group are households which have access to banks’ outreach.

Figure A3.

Distribution of propensity scores between treatment and control groups after matching: banks’ training. Note: The treatment group are households which received banks’ training.

References

- Honohan, P. Cross-country variation in household access to financial services. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 2493–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, R.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Morduch, J. Microfinance meets the market. J. Econ. Perspect. 2009, 23, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armendáriz, B.; Szafarz, A. On Mission Drift in Microfinance Institutions; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2011; Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/31041/1/MPRA_paper_31041 (accessed on 3 December 2021).

- Copestake, J. Mainstreaming microfinance: Social performance management or mission drift? World Dev. 2007, 35, 1721–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Fund for Agriculture Development. Assessing and Managing Social Performance in Microfinance; IFAD: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thrikawala, S.; Locke, S.; Reddy, R. Social performance of microfinance institutions (MFIs): Does existing practice imply a social objective? Am. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 2, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Awaworyi Churchill, S. Microfinance financial sustainability and outreach: Is there a trade-off? Empir. Econ. 2020, 59, 1329–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeller, M.; Meyer, R. The Triangle of Microfinance: Financial Sustainability, Outreach and Impact; IFPR-International Food Policy Research Institute, The John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, M.; Mosley, P.; Simanowitz, A. The social impact of microfinance. J. Int. Dev. 2004, 16, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtamakaya, C.; Kessy, J.; Jeremia, D.; Msuya, S.; Stray-Pedersen, B. The impact of microfinance programmes on access to healthcare, knowledge of health indicators and health status among women in Moshi, Tanzania. Tanzan. J. Health 2018, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, K.S.; Azam, M.S. Does Microfinance reduce poverty in Bangladesh? New evidence from household panel data. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 48, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumah, A.; Boachie, W.K. An investigation into the impact of microfinance in poverty reduction in less developed countries (LDCs): A. case of Ghana. Am. Sci. Res. J. Eng. Teach. Sci 2016, 6, 188–201. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath, P. Microfinance and the decision to invest in children’s education. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2018, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Conzo, P. The effect of microfinance on childs schooling: A retrospective approach. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2014, 24, 9–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, F. Social Rating and Social Performance Reporting in Microfinance: Towards a Common Framework; Argidius Foundation and The SEEP NETWORK: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, S. Beyond Good Intentions: Measuring the Social Performance of Microfinance; Focus Note; CGAP: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maitrot, M. The Social Performance of Microfinance Institutions in Rural Bangladesh. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Annim, S.K. Outreach and poverty-reducing effect od microfinance in Ghana. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2018, 29, 145–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norjo, R.C.; Adjasi, C.K.D. The Impact of Finance on the Welfare of Smallholder Farmers Household in Ghana; IAAE: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nyeadi, J.D.; Kunbuor, V.K.; Ganaa, E.D. Innovation and Firm Productivity: Empirical Evidence from Ghana. Acta Univ. Danubius. Acon. 2018, 14, 127–140. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Mohnen, P.; Zanello, G. Innovation and productivity in formal and informal firms in Ghana. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 131, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, H.H.; Asad, M.; Fatima, M.; Abidin, R.Z.U. Microfinance and performance of micro and small enterprise; Does training have an impact. J. Entrep. Bus. Innov. 2017, 6, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, S.R. Poverty outreach and BRACs’s microfinance interventions: Programme impact and sustainability. IDS Bull. 2003, 34, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Peprah, J.A.; Koomson, I.; Sebu, J.; Bukari, C. Improving productivity among smallholder farmers in Ghana: Does financial inclusion matter? Agric. Financ. Rev. 2020, 81, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, B.O. The Failure of microfinance in Ghana: A case study of Noble Dream microfinance limited. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 53, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, F.G.; Nortey, S.; Barnie, J.A.; Dwumah, P.; Acheampong, M.; Ackom-Sampene, E. Collapsing microfinance institutions in Ghana: An account of how four expanded and imploded in the Ashanti Region. J. Afr. Dev. 2016, 3, 37–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ofori, E. The effects of ponzi schemes and revocation of licenses of some financial institutions on financial threat in Ghana. J. Financ. Crime 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. The Budget Statement and Economic Policy of the Government of Ghana for the 2019 Financial Year, Budget Paper; GOG: Accra, Ghana, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GSS. Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS7): Poverty Trends in Ghana 2005–2017; Ghana Statistical Services: Accra, Ghana, 2018; pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, P.L. The evolution of corporate social responsibility. Bus. Horiz. 2007, 50, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, N.; Tang, S.Y. Delivering microfinance in developing countries: Controversies and policy perspectives. Policy Stud. J. 2001, 29, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conning, J. Outreach, sustainability and leverage in monitored and peer-monitored lending. J. Dev. Econ. 1999, 60, 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, M.; Matul, M. Realizing mission objectives: A promising approach to measuring the social performance of microfinance institutions. J. Microfinance ESR Rev. 2004, 6, 2–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, P.; Rock, J. Microfinance, labour markets and poverty in Africa: A study of six institutions. J. Int. Dev. 2004, 16, 467–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, F.M. Social Performance of Microfinance Institutions: Theory and Empirical Evidence. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hohenheim Stuttgart, Stuttgart, Germany , 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Doligez, F.; Rennes, I. Stakes of Measuring Social Performance in Microfinance; SPI3—Discussion Paper; CERISE: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]