1. Introduction

Sustainability, as a strategy, is the responsible utilization of resources. The thinking of sustainability consists of three dimensions: environmental, social, and economic sustainability [

1]. As revealed by United Nationals Social Compact, social sustainability identifies and manages business impacts on people [

2]. Companies affect employees, supply chain workers, customers, and local communities [

3]. Companies are now trying to be more responsible because of the mandated Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) policy, and, thus, sustainability through social factors is gaining more prominence [

3]. Social capital, an essential constituent of social sustainability, is important because it reduces economic transaction costs [

4]. Social demands force firms to show off their present offerings to society concerning sustainability issues. Companies link their decisions to sustainability impacts—including societal effects [

5]. Successful social sustainability approaches involve consumer perception on sustainable marketing performance [

6] and brand competitiveness [

7]. Consumer-based CSR relations reveal a firm’s status and activities with respect to perceived social obligations [

8].

Companies are expected to bring positive impacts on people to obtain social sustainability. Nevertheless, companies may go against the mainstream public opinion for controversial social issues due to their own ideology. The arguments for the controversial social issues may attract both supporters and opponents from the public. People who are dissatisfied with a company’s viewpoint on controversial social issues may find them dissatisfactory and even boycott the companies. Unethical behavior of a company may also bring negative impacts on social sustainability and damage the trustworthiness of companies. Consumers may distrust and even boycott the companies because of their misconduct.

Companies usually conduct marketing efforts to build brand equity to obtain brand sustainable development. As the internet and social media become ever more popular, social media becomes an essential component of marketing and enables companies to connect with the market in a real-time manner [

9]. Companies use social media as a channel for convenient marketing communication. They participate in social issues, strengthen their brand image, and practice CSR communication to maintain para-social relationships (PSR) with their customers [

10].

Consumers can also easily express their opinions on social media as word-of-mouth. Social media also enables consumers to share their comments about a product or service [

10]. Consumers usually search for word-of-mouth before choosing a product to purchase [

11]. In addition, consumers are now more willing to express their opinions and no longer hide their hatred for liked or disliked brands. When customers establish para-social interactions on the internet, the brand’s public position will impact the customer–brand relationship [

12]. The accumulated positive word-of-mouth may increase brand equity. By contrast, the accumulated negative word-of-mouth in the online space may gradually produce consumer hate for the company or brand [

13].

Brand hate damages brand equity, which is an obstacle to brand sustainability. There are many reasons why consumers hate brands. Three kinds of main external factors may cause consumers to feel hate: (1) negative brand experience, (2) symbolic inconsistency, and (3) incompatibility with the brand’s ideology [

14]. Consumer hate may be caused by consumers’ angry reactions to political, military, economic, or diplomatic events that affect the consumers’ purchase behavior [

15].

Brand hate may cause consumers to take actions, such as brand avoidance, boycott, or other hateful consumer behavior. It can range from mild (hate criticism or negative word-of-mouth) to severe retaliation, such as boycott for buying behaviors [

16]. Boycott as anti-consumption behavior, initiated voluntarily by consumers, has been occurring for decades, and consumer groups have increasingly used boycotting behaviors to express dissatisfaction with companies and brands [

17]. The literature has shown that boycotts could affect both companies and brands [

18]. Significantly, when the boycott activities of consumers are spread using the media, then those boycotts can threaten the tangible and intangible resources of the companies or brands. Due to these boycotts, both companies and brands are “forced” to accept a consumer argument. As the media pays ever more attention to consumer boycotts, these boycotts can easily hurt a company or a brand, severely [

18].

When consumers’ viewpoints on social or political issues conflicts with a brand’s viewpoints, viewpoint inconsistency may cause consumers to hate that brand. The literature has discussed consumers’ reactions to the difference in ideologies between consumers and a brand for an actual boycott event. For example, in the case of Barilla, an international food company [

19], the company triggered consumer boycott action because of the company chairman’s statement against same-sex families in a radio interview. Consumers then spread #boycottbarilla and other similar tags on Twitter to boycott the company. Yet another study [

20] examined brand hate due to a certain religious stance, which caused consumers to boycott that brand. Saudi Arabia boycotted Danish-made products due to the disrespect in the content of Danish newspapers toward the prophets of Islam.

However, individual consumers’ opinions toward a company or brand are not always compatible with those of their relatives or friends. When individuals’ views are different from others, and the uncoordinated situation called “collective cognitive dissonance “ happens [

21], consumers need to choose to keep their own opinions on boycotts or change their stance and views to follow others’ thoughts on boycotts and reduce the collective dissonance. Attention to Social Comparison Information (ATSCI) refers to a person’s sensitivity to social comparison information. High ATSCI individuals pay much attention to others’ reactions [

22]. Thus, ATSCI may be a moderate factor for influencing others’ viewpoints on individual consumer boycott intentions.

Although many previous studies have focused on consumer hate and boycott, few studies, if any, have explored the impact of viewpoint incompatibility and the moderate effect of ATSCI on brand boycott. Thus, the current article seeks to address the following research questions:

- RQ1:

Will viewpoint incompatibility between individual consumers and the brand position influence individuals’ intentions to boycott?

- RQ2:

What is the moderate effect of ATSCI on the influence of the public’s viewpoint on individual consumers’ boycott intentions?

In the following sections, we introduce the theoretical background (

Section 2), brand hate and consumer boycotts (

Section 2.1), collective cognitive dissonance (

Section 2.2), attention to social comparison information (

Section 2.3), our methodology (

Section 3), our hypotheses (

Section 3.1), three empirical studies (

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3, and

Section 3.4), and explain the research findings and conclusions (

Section 4).

3. Methodology

3.1. Hypotheses

Brand hate is generated by people based on their past beliefs and the ongoing hostilities between brands [

30] and will lead to passive behaviors, such as avoiding brand use, negative word-of-mouth and brand revenge [

14]. The boycott is one way for consumers to present their dissatisfaction with the company [

36] and their corporate socially irresponsible behaviors [

29].

Viewpoint incompatibility between consumers and a brand is a reason for consumer boycotts [

39]. Incompatibility with a brand’s ideology leads to brand hate, which will increase brand retaliation (negative criticism and boycott) arising from brand hate [

14]. Islam, Attiq, Hameed, Khokhar and Sheikh [

34] indicated that the inconsistency between the symbolism and functionality of a brand can be the leading cause of brand hatred and determining consumption behaviors.

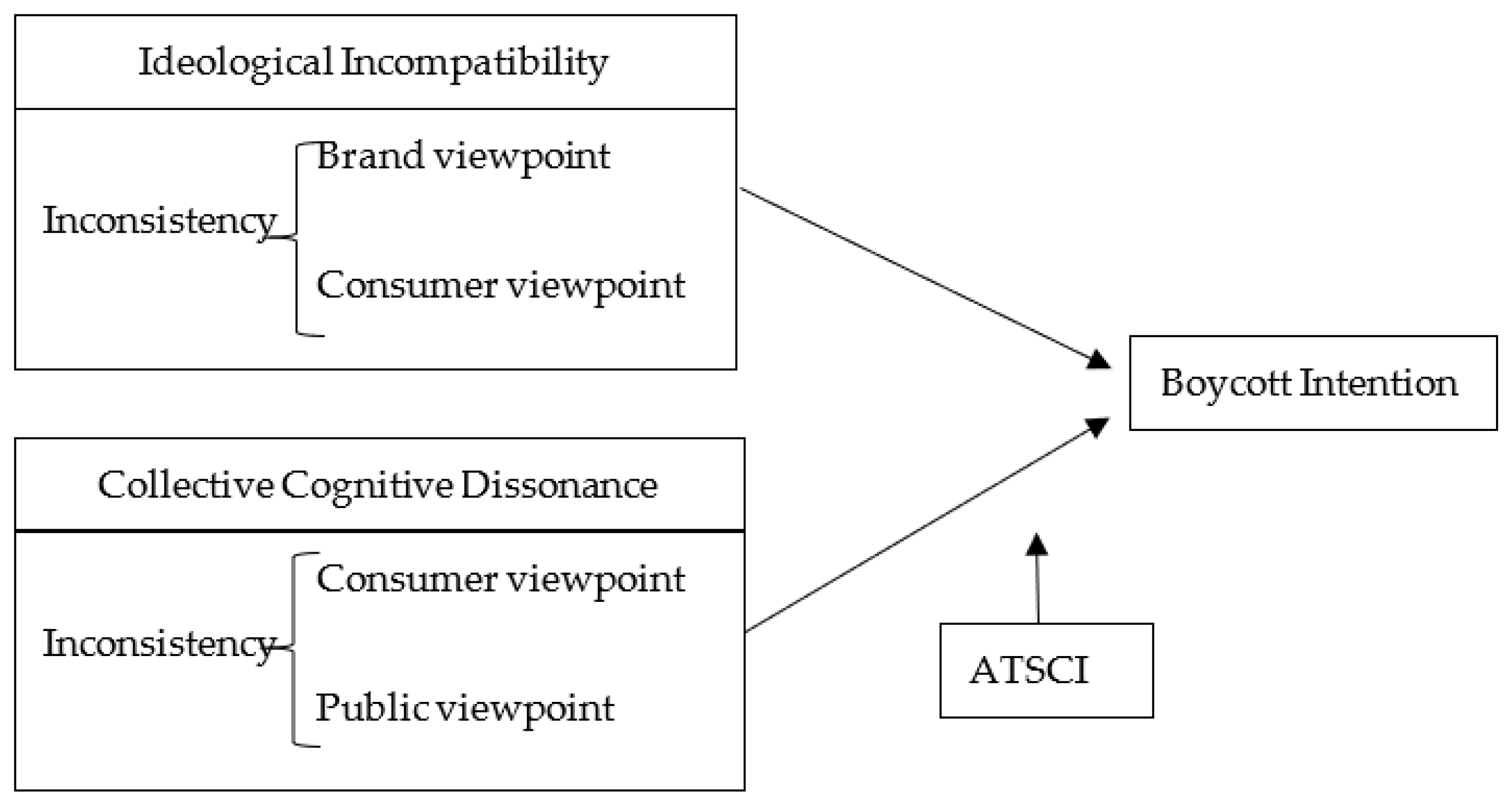

When an individual has an incompatible ideology with a brand, that individual cannot agree with the viewpoint that the brand publicly expresses. This ideological incompatibility will make consumers feel negatively about that brand, increase their hatred of the brand, and increase their intention to boycott. In other words, when an individual has conflicting opinions with a brand, then that individual will resist purchase and increase the boycott intention to oppose the brand’s ideology. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Viewpoint incompatibility of the social dispute between individuals and the brand is positive relative to individuals’ boycott intention to the brand.

Cognitive dissonance appears when an individual feels intrinsic conflict due to holding two different cognitions [

44]. Individuals tend to abandon or change one of these cognitions to achieve a harmonious state of mind. The idea of collective cognitive dissonance is the phenomenon when individuals feel cognitive dissonance because their opinion is not compatible with that of others [

21]. In a boycott event, not all consumers agree (disagree) to boycott the brand. Consumers may hold conflicting opinions to that of others toward the company or brand.

People usually compare themselves to others to self-assess and self-enhance [

48]. After that comparison, they may find viewpoint incompatibility with others, which leads to a collective cognitive dissonance that makes them feel conflicted and uncomfortable [

21]. To achieve a harmonious and compatible state of mind, individuals may avoid messages that are different from their own positions or actively debate with people who have different positions.

When viewpoint inconsistency exists toward boycott activities, people have two approaches that they can use to solve the collective cognitive dissonance within a social group: change their own opinion to follow others, or do not consider the opinions of others. People who pay great attention to social comparison information (ATSCI) tend to pay greater attention to the opinions of others [

22] and compare their opinions to those of others. They will seek to agree with others’ thinking or behavior because they are afraid of getting negative judgments from others [

49].

Thus, when an individual consumer’s viewpoint is incompatible with others, the boycott intention of high ATSCI individuals may be influenced significantly by those others. In contrast, low ATSCI individuals might not consider the viewpoint of others. When consumers have the same viewpoint as the brand, but it is incompatible with the perspective of the mainstream opinions, high ATSCI individuals will follow the others’ opinion to boycott the brand, even if they originally hold the same viewpoint as the brand. Low ATSCI individuals that have the same viewpoint as the brand will follow their own opinion of not boycotting the brand.

In contrast, when consumers have a different viewpoint with the brand, but the mainstream opinion agrees with the brand, a collective cognitive dissonance also exists. In this scenario, high ATSCI individuals will follow the others’ opinion not to boycott the brand, even they hold a different viewpoint about the brand. Low ATSCI individuals will follow their own opinion toward boycotting the brand.

Based on the discussion mentioned above, we propose Hypothesis 2 as follows:

Hypothesis 2: When an individual consumer’s viewpoint is incompatible with that of others, the attention given to social comparison information (ATSCI) will moderate the individual consumer’s intention to boycott. High ATSCI individuals will follow the viewpoint of others, while low ATSCI individuals will follow their own viewpoint.

Figure 1 illustrates the research model.

3.2. Study 1

Study 1 explored the influence of viewpoint incompatibility between individual consumers and the brand for consumer boycott intention.

3.2.1. Design

Study 1 designed an experimental scenario as follows:

A pseudo tea beverage shop is presenting their stand on the social dispute regarding the legalization of same-sex marriage.

The legalization of same-sex marriage is a debated issue in many countries around the world, including Taiwan. Same-sex marriage in Taiwan became legal on 24 May 2019, and that made Taiwan the first country in Asia to legally allow same-sex marriages. However, not all Taiwanese citizens agree with the legalization of same-sex marriage. It is an ongoing disputed social issue.

Study 1 created two pseudo scenarios as an experimental treatment of this issue: a brand takes a stand that supports the legalization of same-sex marriage, or this brand takes a stand opposing the legalization of same-sex marriage. The same brand plays in two pseudo scenarios to recruit different samples.

Study 1 recruited subjects to express their views on the legalization of same-sex marriage. Subjects were randomly assigned to two scenarios—brands that support or oppose the legalization of same-sex marriage. After reading the experimental scenario, the subjects were asked to indicate their intention to boycott the pseudo brand.

3.2.2. Procedure

Study 1 randomly assigned subjects to one of the scenarios. In the created pseudo scenario, subjects were provided pseudo news reports that mentioned the tea beverage shop, presenting their viewpoint about same-sex marriage legalization as follows:

Scenario of supporting same-sex marriage legalization:

“To celebrate the legalization of same-sex marriage, the tea beverage shop has started a promotion that when consumers say “love wins,” they will get a discount on the beverage. Also, the slogan “Celebration of Marriage Equality” (supporting same-sex marriage) is written with rainbow color on the cup (the rainbow color represents the symbolic support of same-sex marriage).

Scenario of not supporting same-sex marriage legalization:

“A tea beverage shop publicly supports an organization that oppose the legalization of same-sex marriage. The organization promotes the traditional family values and insist that marriage should exist only between one man and one woman. This situation has triggered criticism online.”

After reading the assigned experimental scenario, respondents were asked to complete the questionnaire.

3.2.3. Measures

The questionnaires included two variables: (1) the subject’s viewpoint on the legalization of same-sex marriage and (2) the intention to boycott the tea beverage shop. All items were measured using a 5-point Likert scale. The respondents were asked to express their views on the issue of legalization of same-sex marriage and the intention to boycott the tea beverage shop from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,”, respectively, ranging from 1 to 5 points. Three questions were then used to measure the respondents’ views on the legalization of same-sex marriage: “Do you agree that the legalization of same-sex marriage will have a negative impact on society (reverse scoring)?”, “Do you agree that same-sex people should have the right to marry?” and “Are you willing to vote for political candidates who support the legalization of same-sex marriage.” If the average of three items is higher than 3, the subjects were considered as supporting the legalization of same-sex marriage. Otherwise, the subjects were considered as opposing the legalization of same-sex marriage. Because the political candidates are public figures, they affect the legalization procedure of same-sex marriage as they are elected. Accordingly, the third item asked subjects’ voting willingness to measure the subjects’ agreement with same-sex marriage. For the intention to boycott scale, we used a 4-item scale that was modified from the scale developed by Dodds, et al. [

55].

3.2.4. Sample

Data were collected from PTT (

http://ptt.cc, accessed on July 2020), the most famous online community in Taiwan in 2020, and 177 subjects voluntarily joined Study 1.

Table 1 shows the demographic profiles of the respondents who participated in Study 1.

To realize the potential moderate effect of marital status and child parenting on the support of the legalization of same-sex marriage, we used an independent sample t-test to discover the difference in viewpoints for same-sex marriage between unmarried and married subjects and between subjects with or without children. There was no significant difference between the married and unmarried subjects (p value > 0.05) and between subjects who were parenting and those who were not parenting children (p value > 0.05).

3.2.5. Reliability and Validity

Table 2 reports the reliability and validity of the measurement scale. Cronbach’s α was used to measure the compatibility of each item under the same dimension. Cronbach’s α of same-sex marriage support was 0.773, while boycott intention was 0.904. Both were greater than 0.70, indicating that the measurement items were reliable.

Confirmatory factor analysis was employed to analyze standardized factor loading, convergent validity, composite reliability (CR), and average variance explained (AVE). Favorable construct validity was indicated by satisfying the criteria CR > 0.6 and AVE > 0.5 [

56].

Table 2 shows that the AVE values of same-sex marriage support and boycott intention were both greater than 0.50. The CR values were both higher than 0.60, indicating the internal consistency of the results. Both AVE and CR scores meet Fornell and Larcker [

57] recommendation. To examine discriminant validity, we referred to Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham [

56], which states that the correlations between the constructs should be lower than the root of the corresponding AVEs. As

Table 3 shows, the correlations between the constructs were lower than the root of the corresponding AVEs, thereby indicating favorable discriminant validity.

3.2.6. Hypothesis Results

Study 1 used an independent sample t-test to analyze the difference in viewpoint compatibility for boycott intention. As

Table 4 reveals, subjects with a different viewpoint than the brand on the legalization of same-sex marriage presented a higher intention to boycott that brand. There was a significant boycott intention difference between the compatible and incompatible viewpoints (t = 7.993,

p < 0.001). These results reveal that when the individual consumer’s view was inconsistent with that of the brand, the individual consumer had a higher intention to boycott the brand.

Many of the subjects in Study 1 supported same-sex marriage. In the scenario where the brand supported same-sex marriage, 77 (89.53%) of the 86 subjects supported same-sex marriage. In the scenario where the brand opposed same-sex marriage, 83 (90.21%) of the 92 subjects supported same-sex marriage (

Table 5). Thus, in the scenario where the pseudo brand supported same-sex marriage, most of the subjects had a compatible viewpoint with the brand. Nevertheless, in the scenario where the pseudo brand opposed same-sex marriage, most of the subjects shared the incompatible viewpoint with the brand.

Since most of the subjects supported same-sex marriage, we had to check to see if the subjects’ support of same-sex marriage was an antecedent for boycott intention. We thus further adopted ANCOVA to analyze the influence on boycott intention of the subjects’ viewpoint, the viewpoint incompatibility between subjects and the brand, and the interaction between a subjective perspective and viewpoint incompatibility.

The ANCOVA analysis results revealed that subject viewpoint was not a significant factor for boycott intention. Instead, viewpoint incompatibility was a significant factor for boycott intention, as

Table 6 shows. The ANCOVA analysis results also reported a significant influence on boycott intention of the interaction between viewpoint and viewpoint incompatibility. Subjects who opposed same-sex marriage had the highest boycott intention of the brand supporting same-sex marriage, although these subjects were the minority in Study 1. Only 9 of the 177 (5.08%) belonged to this group.

3.3. Study 2

In Study 1, the subjects were recruited from a famous online community (Ptt.cc) in Taiwan. Most of them were active users in that online community. Most subjects of Study 1 were youth, and 86% were under 35. Among them, most subjects (90%) reported that they supported the legalization of same-sex marriage and only 10% opposed the legalization of same-sex marriage. The unbalanced ratio of support and opposition to the legalization of same-sex marriage was an issue of sample representativeness. To confirm the generalized ability of these research findings, Study 2 recruited diverse subjects from a park with kids and elders to collect more samples of elders and parents. Elders and consumers who are parenting kids might oppose the legalization of same-sex marriage.

3.3.1. Sample

Study 2 adopted a hard-copy questionnaire and recruited subjects in a park in Taipei, Taiwan. The research design and procedure for Study 2 were the same as for Study 1 (

n = 247).

Table 7 shows the demographic information of the respondents involved in the survey.

To realize the potential moderate effect of marital status and child parenting on supporting the legalization of same-sex marriage, we used an independent sample t-test to realize the difference in viewpoint on same-sex marriage between unmarried and married subjects and between subjects with or without children. The t-test result shows that in terms of supporting the legalization of same-sex marriage, there was a significant difference between unmarried and married people (p-value < 0.05) and between having children and not having children (p-value < 0.05). The results of Study 2 are different from those of Study 1. Thus, based on the samples from the public space, we can conclude that marital status and parenting are important for supporting the legalization of same-sex marriage.

However, the research focus of this article is not on supporting the legalization of same-sex marriage. Instead, we focus here on the influence of viewpoint incompatibility on boycott intention. To avoid any loss of focus in this current article, we do not discuss here the impact of marital status and parenting.

3.3.2. Reliability and Validity

Table 8 shows the reliability and validity test results for Study 2. Cronbach’s α for both same-sex marriage support and boycott intention was greater than 0.70, indicating that the measurement items were reliable. AVE values for same-sex marriage support and boycott intention were greater than 0.50, and CR values were both higher than 0.60, indicating an internal consistency of results. Both AVE and CR scores met the Fornell and Larcker [

57] recommendation. In

Table 9, the correlations between the constructs were lower than the root of the corresponding AVEs, thus indicating good discriminant validity [

56].

3.3.3. Hypothesis Results

Study 2 also used t-test and ANCOVA to test Hypothesis 1. As

Table 10 reveals, there is a significant difference in boycott intention between subjects with a compatible and incompatible viewpoint of the brand (t = 8.973,

p < 0.001). These results reveal that when individual consumers’ viewpoints are incompatible with that of the brand, they will have a higher intention to boycott that brand.

In Study 2, 169 (68.42%) of 247 subjects supported same-sex marriage, which was lower than Study 1. In the scenario of brand supporting same-sex marriage, 83 (65.35%) of the 127 subjects supported same-sex marriage. In the scenario where the brand opposed same-sex marriage, 86 (71.66%) of the 120 subjects supported same-sex marriage (

Table 11). The support to oppose ratio was more balanced than that for Study 1.

We adopted ANCOVA to analyze the influence on boycott intention of subject viewpoint, viewpoint incompatibility between subjects and the brand, and the interaction between subjective viewpoint and viewpoint incompatibility. The ANCOVA analysis results revealed that subject viewpoint was not a significant factor for boycott intention (

p = 0.088). Nevertheless, viewpoint incompatibility was a significant factor for boycott intention (

p < 0.001), as shown in

Table 12.

The ANCOVA analysis results reported the significant influence on boycott intention of viewpoint incompatibility (p < 0.001). Subjects who oppose same-sex marriage had the highest boycott intention for the brand supporting same-sex marriage. The significant influence of interaction means that the personal viewpoint moderated the influence on the intention to boycott and was impacted by whether the personal viewpoint was compatible with the brand’s viewpoint or not. This result showed that individual consumers who hold a different viewpoint with the brand have a higher intention to boycott, which supports H1.

3.4. Study 3

Study 1 and Study 2 explored the influence of viewpoint incompatibility between subjects and the brand. However, viewpoint incompatibility may exist between individual consumers and others, such as their relatives and friends. People feel collective cognition dissonance when they find that their viewpoint toward the brand is different from the viewpoint of others. To reduce collective cognition dissonance, people may change their viewpoint to follow others. In contrast, people may also ignore others’ viewpoints and hold their own viewpoint. ATSCI is a moderator for influencing others’ viewpoints on consumers’ boycott intention when there is existing collective cognition dissonance.

Study 3 examined the moderation of ATSCI on individual boycott intention when the personal viewpoint was in an opposite position to that of others.

3.4.1. Design

Study 3 used a real case of a milk brand boycott in its experiment design. However, the authors decided not to mention the brand name in the article because the brand itself is not the major focus of Study 3. Before 2013, the targeted milk brand was the leading brand with the top market share in Taiwan. The milk brand is a product of the second-largest food manufacturer company, which is a subsidiary of a large food group company that has business in both Taiwan and Mainland China. In 2014, another subsidy of that group company was involved in a tainted cooking oil scandal in Taiwan. Consumers boycotted the milk brand because the milk brand belongs to the same group company as the tainted cooking oil. In 2016, the milk brand slid back to second position in market shares. In 2020, the market share of the milk brand is still recovering but is yet not back to holding its original market share.

Some consumers keep boycotting the milk brand, while other consumers have ceased the boycott since the milk company is not the same company that produced the tainted cooking oil. The milk brand is a debated brand since some consumers think that the milk brand is innocent and that the boycott should not extend to the milk brand. However, some consumers believe that the boycott should include all brands and all subsidy companies that belong to the same group company to make sure that the boycott is successful. It is a suitable example for exploring the phenomenon of collective cognition dissonance among consumers regarding boycotts.

Study 3 compares the consumer boycott intention for two scenarios of collective cognition dissonance: the consumers have low brand identification while others agree on high brand identification, and the consumers had low brand identification while others had high brand identification.

At the beginning of the questionnaire, the respondents reported on their degree of ATSCI and the degree of brand identification toward the brand. The real brand name was used in the experiment. The subjects were presented with the following statement:

“Image that you drink milk for breakfast every morning. One day, when you go to school/work, you walk into a convenience store and find that there are only the BRAND’s products on the shelf.”

After reading the statement, the subjects were randomly assigned to one of the following scenarios:

The scenario of others with high brand identification:

“Most of the other consumers, such as your relatives and friends, like the Brand. They usually recommend this brand product to you. If you do not purchase or like the product of the brand like them, they will feel upset and disappointed about it.”

The scenario of others having low brand identification:

“Most of the other consumers, such as your relatives and friends, dislike the Brand. They persuade you not to purchase the product of the brand products. If you still purchase or like the products, they will feel upset and disappointed about it.”

Then the respondents were asked to indicate their boycott intention for the assigned scenario.

3.4.2. Measures

Study 3 used the 13-item ATSCI scale initially developed by Bearden and Rose [

22]. To measure brand identification, Study 3 adopted a four-item brand identification scale that was modified from the scale developed by Mael and Ashforth [

58]. To measure boycott intention, Study 3 adopted five items that were revised from the scales used in Dodds, Monroe and Grewal [

55]. All items were measured using a Likert-type 5-point scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Subjects were divided into high and low brand identification groups according to their average brand identification score. High brand identification subjects were those with an average brand identification score greater than or equal to 3.

3.4.3. Sample

Data were collected in an online community Ptt.cc in December of 2020. In Study 3, a total of 253 valid samples were collected. The high brand identification scenario (others had high brand identification) contained 125 valid samples. Of them, 44 (35.20%) subjects had high brand identification and were compatible with the viewpoints of others. 81 (64.80%) subjects had low brand identification and were with incompatible viewpoint of their relatives and friends (details in

Table 13).

Low brand identification scenario (others had low brand identification) contained 128 valid samples. Of them, 69 (53.91%) subjects had low brand identification and compatible viewpoints with their relatives and friends. The remaining 59 (46.09%) had incompatible perspectives with others.

3.4.4. Reliability and Validity

Table 14 indicates the reliability and validity test results for Study 3. Cronbach’s α of ATSCI, brand identification, and boycott intention were all greater than 0.70, indicating that the measurement items were reliable. AVE values were all greater than 0.50, CR values were both higher than 0.60, indicating an internal consistency of results. Both AVE and CR score met the Fornell and Larcker [

57] recommendation. The correlations between the constructs were lower than the root of the corresponding AVEs, thereby indicating favorable discriminant validity [

56], as

Table 15 shows.

3.4.5. Hypothesis Test Results

Study 3 focuses on the moderated effect of ATSCI on the influence of viewpoint incompatibility on boycott intention. To test Hypothesis 2, Study 3 only considered subjects with an incompatible viewpoint with the others. There were two groups of subjects that had an incompatible viewpoint with others. The first group (Group 1) included subjects with low brand identification, but others had high brand identification (n = 81). The second group (Group 2) included subjects with high brand identification, while others had low brand identification (n = 59).

In Group 1, an incompatible viewpoint existed since subjects had low brand identification while others had high brand identification.

Table 16 shows a significant difference in boycott intention between high and low ATSCI subjects (t = 2.933,

p = 0.004). High ATSCI subjects followed others’ viewpoint (high brand identification) and had a lower intention to boycott the brand (mean = 3.361, s.d. = 0.884). Nevertheless, low ATSCI subjects followed their own mind (low brand identification) and had a higher intention to boycott the brand (mean = 4.100, s.d. = 0.839).

In Group 2, an incompatible viewpoint exists since some subjects had high brand identification while others had low brand identification.

Table 17 shows a significant difference in boycott intention between high and low ATSCI subjects (t = −3.414,

p < 0.001). High ATSCI subjects followed the viewpoint of others (low brand identification) and had a higher intention to boycott the brand (mean = 3.479, s.d. = 0.650). Nevertheless, low ATSCI subjects followed their own minds (high brand identification) and had a lower intention to boycott the brand (mean = 2.162, s.d. = 0.522).

Based on the t-test analysis results of

Table 16 and

Table 17, H2 was supported.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

A boycott is a type of anti-consumption behavior initiated voluntarily by consumers to express their dissatisfaction with brands [

17]. There are plenty of reasons that cause consumers to be dissatisfied or hate a brand. Negative brand experience is a reasonable reason to brand-hate and boycott [

14]. However, not all consumers boycott because of their negative consumption experience of the brand. Ideological incompatibility is another reason for consumer boycotts. The literature has argued that ideology incompatibility between consumers and a brand is a potential reason for consumers to hate brands [

14,

15,

39]. It may cause consumers to take boycott actions to express their dissatisfaction with the brands [

17].

The current article uses three empirical studies to discuss the influence of viewpoint incompatibility on the boycott actions for individual consumers, the brand, and other consumers. Study 1 and Study 2 examined viewpoint incompatibility between the brand and the consumers. Study 3 discusses the viewpoint incompatibility among consumers. Based on the results of Study 1 and Study 2, we found that when consumers’ viewpoints are incompatible with that of the brand in any social dispute, consumers might have a high intention to boycott that brand. Some consumers choose to take boycott action because the brand chooses to take a position that the consumer disagrees with for a social dispute. The results of Study 1 and Study 2 confirmed the argument proposed in the literature that ideology incompatibility is one reason for consumer boycotts [

39].

Consumers’ opinions are diversified. Individual consumers may have their own opinions of a brand. In a consumer boycott event, not all consumers take action to boycott the brand. Some consumers have a strong intention to boycott the brand, while others may believe that the brand does not deserve to be boycotted. It is not pragmatic to consider all consumers as same in a consumer boycott event. When individual consumers’ opinions toward the brand are not the same as their relatives or friends, then collective cognitive dissonance may appear. Consumers must decide whether insist on their own viewpoint on boycott or change their viewpoint to follow others’ viewpoints. Consumers’ sensitivity to social comparison information can be a moderator for boycott intention. The literature has advocated that when consumers have high ATSCI, they will pay more attention to other consumers’ reactions. [

22]. ATSCI is a moderator when discussing consumer boycott action.

Based on Study 3, we conclude that ATSCI will moderate the influence of viewpoint incompatibility between the brand and consumers on boycott intention. High ATSCI individuals will follow the opinions of others. Alternatively, low ATSCI individuals will follow their own minds and ignore other consumers’ opinions. The results of Study 3 supported the argument in the previous literature that high ATSCI consumers will follow the behavior of other consumers [

50] and assimilate into the majority in the social environment.

4.1. Theoretical Contribution

The literature has explored the structure of emotions regarding brand hatred [

31] and the reasons why consumers have hated emotions [

15]. Consumers’ brand hatred will impact brand loyalty and induce individuals to resist that brand [

18]. Brand hatred will also lead to passive behavior, such as brand avoidance, and active behavior, such as a boycott.

Based on the three empirical surveys conducted for this paper, we agree with the prior literature, but also contribute additional academic arguments by asserting that incompatible viewpoints of brand, consumers and the public are an antecedent of consumer boycotts. We also contribute to academics by proposing that individuals’ ATSCI is a moderator for consumer boycotts when viewpoint incompatibility exists among individual consumers.

Few previous studies, if any, have adopted empirical studies or experimental designs to discuss the influence on consumer boycotts of viewpoint incompatibility between consumers and the brand. The current article contributes to academia by adding viewpoint incompatibility on debatable social issues as a potential reason for consumer boycotts. Some consumers boycott the brand, but not because of a negative consumption experience. Instead, they boycott the brand because of incompatible viewpoints on social disputes.

Another theoretical contribution of the current article is its discussion of the moderating effect of consumers’ focus on social attention information regarding consumer boycotts. The literature proposes the concept of collective cognitive dissonance, which refers to the uncoordinated situation wherein individuals’ viewpoints are different from the others in a group [

21]. Consumer attention to social attention information (ATSCI) can be considered a personal trait that pays attention to others’ behavior. High ATSCI consumers have higher assimilation needs with their peers in order to follow others’ expectations [

22].

The current article contributes to academia by using the concept of the collective cognitive dissonance phenomenon to discuss viewpoint incompatibility among consumers in consumer boycotts. This study explains the real practice in any consumer boycott event, i.e., not all consumers will agree with the boycott action. Individual consumers may have their own viewpoint on the boycott action. Individuals’ ATSCI traits may be a moderating factor for following others’ viewpoint or insisting on their own viewpoint of the boycott event when an incompatible viewpoint does exist among the brand consumers.

The boycott is a threat to the brand’s sustainable development. The targeted brand of consumer boycotts can suffer many consequences, including a damaged brand image and decreased consumer loyalty. The literature has discussed consumer boycotts. Nevertheless, the literature has seldom discussed the influence on the boycott of a viewpoint that is incompatible with the brand, the individual consumers, and the public. This article adopts a different perspective from the previous boycott literature by discussing the incompatible viewpoint. This article also examines the moderation of ATSCI on boycott intention, while there is still existing collective cognitive dissonance among consumers. It, thus, complements the theoretical views that have been seldom discussed in previous literature.

The previous literature has mostly focused on the view that consumers are dissatisfied with a brand or are incompatible with the brand’s standpoint. Nevertheless, some consumers may have the same viewpoint as the brand but have a different viewpoint than other majority consumers. Consumers who like the brand or have the same viewpoint as the brand were ignored in the previous literature. The current article advocates that these consumers may take boycott action because their high ATSCI traits make them follow the actions of the majority. The current article, thus, starts a theoretical discussion on the influence of viewpoint inconsistency on boycott action.

4.2. Practical Contribution and Managerial Implication

In the internet age, consumers are no longer passive information receivers. Consumers can also play an active role in information broadcasting to express their opinions and word-of-mouth on positive or negative consumption experiences to others on social media. They can even initialize or join boycott action to present their serious negative feelings to the brand. The rapid information flow that occurs on social media empowers consumers to speak for themselves, express their thoughts and even call for action to boycott a brand.

To build brand equity, firms adopt a series of marketing activities to earn consumer identification. Companies commit to CSR to earn brand love in long-term relationships. However, this study showed the cruel result that brand hate and boycotts are serious obstacles to brand equity sustainability. Companies cannot and should not ignore the influence of brand hate and boycott in brand management.

Brand managers should be aware that a consumer boycott is not just induced from a negative consumption experience or low product performance. At certain times, consumers involve in a boycott action are not just dissatisfied with the product or service of that brand. Instead, consumers may feel dissatisfied with the brand’s ideology and the position that the brand takes on controversial social issues. The brand, the firm, or the senior executives of the firm may intentionally or unintentionally stand on a position of a social dispute. Brand managers should think carefully about whether their brand needs to claim an argument since viewpoint incompatibility is a potential reason why some consumers do decide to boycott a brand. Based on the empirical study results of the current article, brand managers should create a social atmosphere wherein most consumers support the brand and keep the boycott participants to only a small group of consumers.

Brand managers should clearly understand the viewpoint of their targeted customers since any viewpoint taken that is incompatible with the brand and its targeted consumers will damage brand equity. In contrast, if the viewpoint of the brand is compatible with that of the target brands, then the targeted consumers may feel close identity with the brand. A compatible viewpoint between the brand and its customers might lead to high brand loyalty.

When the brand holds a viewpoint that is incompatible with that held by the general public, that incompatible viewpoint may decrease the public’s identification with the brand and raise many consumers’ intention to boycott or criticize the brand. Thus, brand managers need to be more cautious about whether their brand wants to publicly support or oppose a social issue and its debate because once they stand and take an opposing direction to their targeted consumers, those consumers may boycott the brand. The boycott will produce a significant negative impact on the brand. For instance, consumers will no longer purchase the products, and the brand’s reputation will be damaged. Therefore, we suggest that brand managers consider the opinions of both online mainstream and actual customers before formulating any coping strategy for a social dispute.

Further, during consumer boycott events, not all consumers support or oppose the brand. In most situations, there is no consensus among consumers: some consumers advocate the boycott, while others refuse to join the boycott. It is common for the existence of incompatible viewpoints among consumers. The brand manager should always be aware of the diverse viewpoints among brand consumers.

The consumer boycott is usually a social movement. Certain aggressive initiators advocate for boycott action. Some consumers present their support for the boycott. However, others are unaware of the boycott or decide not to join it for various reasons discussed here. Incompatible viewpoint on any boycott action is not unusual among consumers. The brand manager should know that a consumer boycott is a collective behavior rather than an individual behavior. Before joining or not joining a boycott, some consumers will consider the mainstream opinions of the society. Other consumers may prefer the idea of their friends and relatives in boycott action, especially for any consumers who have the personal trait of paying attention to others and following their point of view.

Most consumers will change their minds to follow the mainstream opinions of the public. Striving for majority consumer support is always essential for effective public relationship management of any boycott crisis. Brand managers may also seek endorsements or supportiveness from celebrities. These trustworthy celebrities are also useful for creating a social atmosphere that supports the brand and thus can reduce the influence of consumer boycotts.

4.3. Research Limitations and Future Studies

The current article is not without some theoretical and methodological limitations, which can suggest the need for future research.

First, the current article focuses only on the influence of viewpoint incompatibility on boycott intention. There are plenty of factors that may influence an individual’s intention to boycott the brand. In Study 1 and Study 2, this article chose the legalization of same-sex marriage as the research target, which is a social dispute without full social consensus in Taiwan. The social norm is an influencing factor for this kind of behavior for a social dispute. Future studies may consider the influence of social norms and use the theory of planned behavior [

59] to identify the impact of social norms on boycott action. Social influence is a potential influence factor for boycotts since a boycott is a collective behavior from consumers.

Further still, the legalization of same-sex marriage is a controversial issue in many societies, including Taiwan. Individuals with either conservative or liberal political stances will likely have different opinions on this issue. Future studies may also consider the moderating effect of conservative or liberal political stances for address, ending, or even avoiding boycotts. Not all subjects were willing to respond on this issue. In a conservative family, same-sex marriage is an untouchable issue. Thus, the current research model should be tested in various societies and countries to example the generalization ability of the research model.

In Study 1, the current article recruited online users as research subjects. Most of the subjects in Study 1 were youths. To avoid the moderating effects of the age and marital status on boycott intention, the current article conducted Study 2, which recruited subjects from the street to obtain more diverse participants. Nevertheless, age and marital status still does influence the issue of the legalization of same-sex marriage. Future studies might focus on the influence of age and marital status on boycott actions related to the legalization of same-sex marriage or other similar age or group-related issues. The age difference is also a direction for future boycott research.

Study 3 used a real brand (not disclosed in this article) as an experimental target. The real brand can obtain external validity. Nevertheless, product quality, brand love, brand identification, brand loyalty, etc., are all potential moderators when discussing the boycott action against a real brand. Future studies should consider the influence of these variables. Future studies might also consider creating a pseudo-brand to obtain better internal validity and reduce the interference effect of product quality, brand love, brand identification, and brand loyalty of a real brand.

Brand awareness, market share, and product type, as well as consumers’ involvement in products, can also be considered as variables when discussing boycott intention in future studies. Future studies can also explore the boycott behavior of various product types and different competitive positions of the brand.