Abstract

This paper documents state-of-the-art research on the impact of social norms on pro-environmental consumer behavior. Our aim was to identify possible research gaps, in particular in terms of the moderating role of culture and self-construal, and to suggest potentially fruitful research avenues. To achieve these objectives, we conducted a systematic review of the literature on the impact of social norms on sustainability over the past 20 years, placing emphasis on the role of culture and self-construal. Altogether, we collected over 16,000 papers via Web of Science and subsequently used NVivo 12 for a fine-grained qualitative analysis. Our findings provide several new insights. First, we identified the most popular research areas, top journals and leading authors in the field of social norms and pro-environmental sustainability. Second, we pinpointed the most popular research topics in the context of the norm–sustainability relationship. Third, we revealed how culture and self-construal have been addressed when researching the connection between social norms and pro-environmental behavior, identified managerial implications, and offered future research directions on the moderating effects of culture and self-construal.

1. Introduction

One of the main problems in promoting sustainable behavior is the attitude–intentions–behavior gap, as people do not always act in line with their sustainability attitudes (e.g., [1,2,3]). In an attempt to bridge this gap, scholars in different disciplines (e.g., sociology, psychology, political science, environmental studies, business research and marketing) have searched for ways to activate pro-environmental behavior (e.g., [4,5]). In this context, different researchers (e.g., [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]) have demonstrated that social norms are especially important in motivating sustainable actions. Social norms originate from cultural standards within a country and can be defined as “cultural rules that guide behavior within a society” [13] (p. 105). Distinguishing between two types of social norms, descriptive (what is commonly done) and injunctive (what is usually approved/disapproved of), Cialdini et al. [6] demonstrated that both norm categories motivate behavior only when they are salient. Building on this work, Goldstein et al. [7] showed that descriptive norms have a stronger influence on sustainable behavior than injunctive norms, in particular when aligned with settings familiar to that of the norm-conforming individuals. Meanwhile, Schultz et al. [9] concluded that actions of others motivate pro-environmental behavior more strongly than monetary advantages or environmental benefits.

While a large body of research, scattered across different areas, has examined the relationship between social norms and sustainable behavior (e.g., [7,10,11,14]), referred to as norm–sustainability relationship, work on possible moderators of this relationship is particularly scarce. A few authors have investigated the effects of self-construal on the norm–sustainability relationship and have shown that the importance of injunctive and descriptive social norms on pro-environmental behavior depends on whether the individual or collective self is activated (e.g., [3,12]). According to the self-construal theory [15], people can be considered as more individualistic (i.e., independent self-construal) or as more interconnected (i.e., interdependent self-construal), and different underlying emotional mechanisms influence pro-environmental behavior of independent compared to interdependent consumers (e.g., [16]). In addition to these personal consumer (micro-level) characteristics, some authors also focused on the macro-cultural level [17] and observed that individualism and collectivism can have a powerful impact on norm conformity [1,6]. However, while individual or collective self-construal on a micro-level and the influence of individualistic and collectivistic cultures on a macro-level have been identified as important potential moderators of the norm–sustainability relationship, the extant research is rather fragmented. For instance, Onwezen et al. [18] looked at individualism and collectivism on a personal and cultural level but focused only on the effects of descriptive norms on sustainable behavior and not on injunctive norms. A paper by Hardeman et al. [19] incorporated both independent and interdependent self-construal, along with individualism on a cultural level, but in respect to norm–sustainability, their study included only personal norms and social norms in general, without distinguishing between descriptive and injunctive norms. Further, while focusing on descriptive norms exclusively, Park et al. [20] looked at culture in general and the effects of high and low self-construal. Thus, to date, there seems to be no comprehensive investigation of the moderating effects of self-construal and culture on all facets of the relationship between norms and sustainability. Consequently, researchers call for a closer investigation of the importance of cultural effects on norm–sustainability (e.g., [21]), as the theoretical understanding of the role of these potentially relevant moderators is important from a theoretical as well as a managerial vantage point.

Our paper responds to this call for additional research and aims to shed more light on the potentially important moderating role of self-construal (independent and interdependent) and culture (individualistic and collectivistic) on the effects of social norms (descriptive and injunctive) on pro-environmental consumer behavior. We propose that analyzing the moderating role of self-construal and culture in the relationship between norms and sustainable consumer behavior is important from a theoretical perspective, as it would offer more of a fine-grained understanding of how and why social norms affect sustainable consumer behavior. From a managerial perspective, we suggest that a better understanding of the role of self-construal and culture would enable the development of more targeted, country-specific international marketing strategies that promote sustainable consumer behavior.

Specifically, we intend to make a contribution by addressing three questions. First, how has the research on the norm–sustainability relationship developed during the last 20 years? The answer will provide a comprehensive overview of the key contributions of this body of research. Second, to what extent has previous work taken account of our focal moderators (independent and interdependent self-construal; individualistic and collectivistic cultures)? This will improve the understanding of the nature of the norm–sustainability relationship and identify knowledge gaps in extant research. Third, what is the methodological and theoretical fabric of the research on the role of self-construal and culture? Together with the insights from the second research question, this will enable the identification of future research avenues designed to close still existing knowledge gaps.

To achieve our objectives, we conducted a systematic interdisciplinary literature review covering the last two decades. Below, we provide an explanation of our methodology followed by the results of the systematic literature review. The discussion of our findings then considers which theoretical and managerial implications can be drawn from the extant body of research and where knowledge gaps still exist. Based on the latter, we suggest avenues for future research on the impact of our focal moderators, self-construal and culture, on the norm–sustainability relationship.

2. Methodology

To provide answers to our research questions, we started by conducting a systematic literature review on the relationship between social norms and sustainability over the past 20 years, focusing particularly on the moderating role of culture and self-construal on the norm–sustainability relationship. A systematic review allowed us to improve the accuracy and reliability of our conclusions by treating the literature as qualitative data [22]. For the purpose of this study, we followed the SALSA model by Booth et al. [22], which consists of a search stage, appraisal, synthesis and analysis.

In the search stage, we collected our material through Web of Science (previously Web of Knowledge), which provides access to journals from different research areas and a search capability that is more refined compared to some other scientific databases, such as ProQuest [23]. Based on a careful screening of several publications on the general topic, we identified the following keywords to help us locate studies relevant for our research:

- (pro-environ* OR sustainab* OR green) behav*;

- soc* norm*;

- self constr*;

- cult*.

We initiated our search with the most widely-used terms in the pertinent literature, namely pro-environmental, sustainable and green. As these terms are frequently used synonymously, we used the ‘OR’ connection. Throughout our search, the use of asterisks (*) permitted a so-called ‘wildcard’ search by representing one or more characters and maximizing the search results for the keywords. As our preliminary analysis of the literature suggested (e.g., [6,7,12]) that the individualism and collectivism dimensions of culture and self-construal may primarily moderate the impact of descriptive and injunctive norms on sustainable behavior, we added three terms to our search criteria, namely:

- (descript* OR injunct*) soc* norm*;

- (individual* OR collectiv*) self*;

- (individual* OR collectiv*) cult*.

In Web of Science, we chose the search field ‘Topic’ (covering search for Title, Abstract, Author Keywords and Keywords Plus) and proceeded by entering different combinations of our keywords. In order to analyze a broader spectrum of literature on pro-environmental consumer behavior and trace the development of research over time, our analysis spanned the beginning of this century to the first quarter of the year 2020. We covered only publications in English and did not confine the search by any additional criteria because we wanted to inspect the variety of approaches to our topic of interest across a range of subject areas.

As can be seen from Table 1, Web of Science returned a total of 16,420 publications on pro-environmental sustainability, of which 1048 papers dealt with social norms. Our Web of Science analysis indicated that of the papers addressing the relationship between social norms and sustainability, 111 also included self-construal and 136 referred to the cultural context; only 20 papers addressed both self-construal and culture.

Table 1.

Web of Science search results.

We identified the most popular journals, authors, research topics and disciplines in our Web of Science results to make comparisons between the research on pro-environmental sustainability and norm sustainability.

3. Literature on Pro-Environmental Sustainability

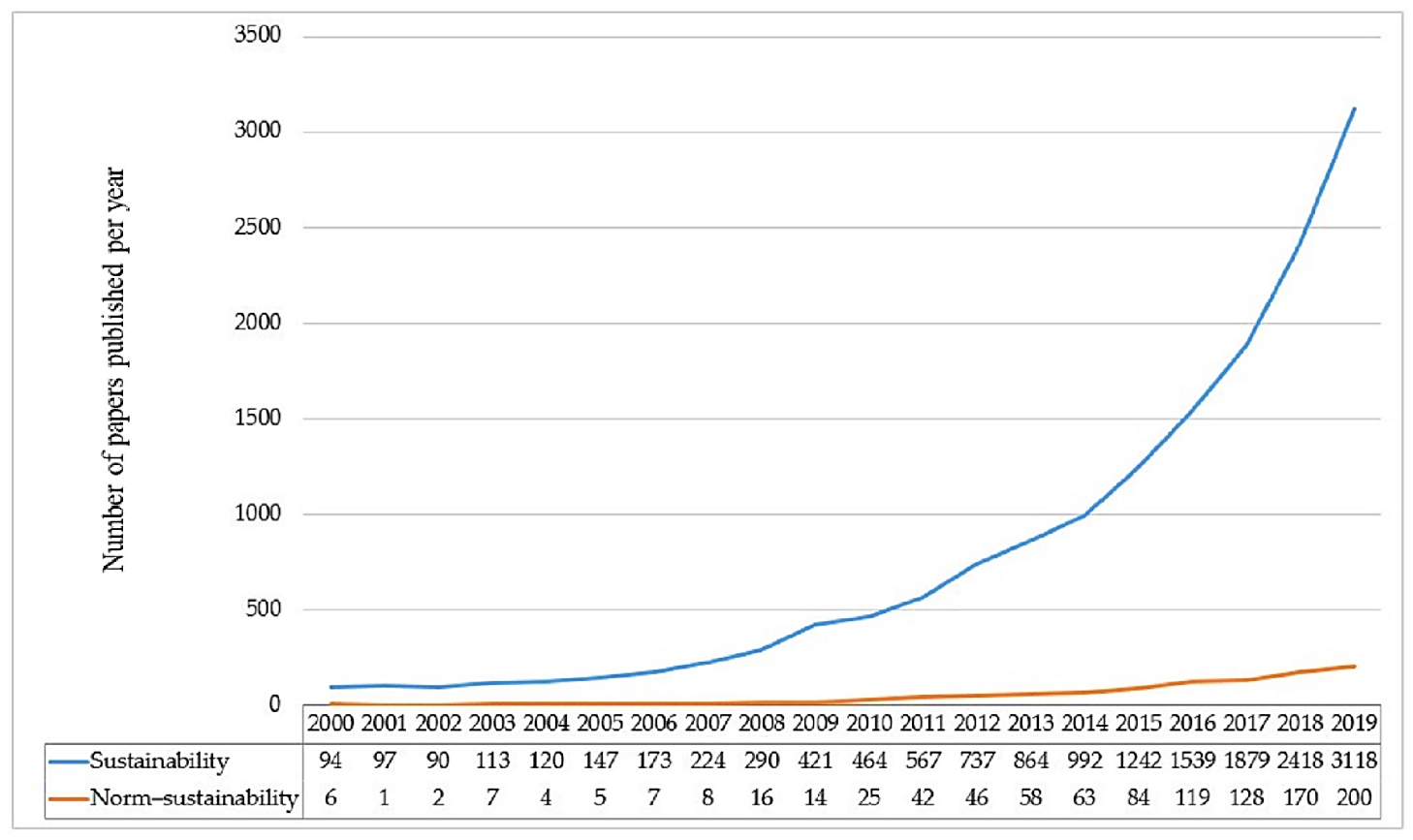

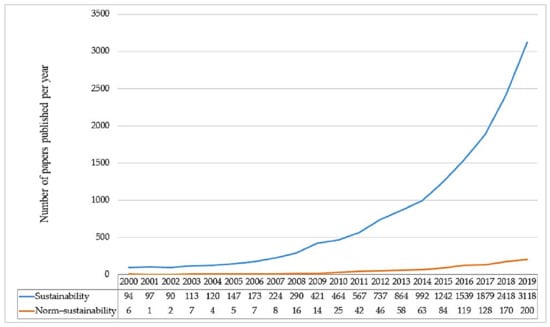

More than two-thirds of papers on pro-environmental sustainability were published after the year 2015, which clearly indicates a rising interest in this field. Although the topic of norm–sustainability accounts only for a small fraction of papers on pro-environmental sustainability, a closer analysis of the publication statistics in Figure 1 shows that the growth of interest in this topic is also quite considerable.

Figure 1.

Publications on sustainability and on the norm–sustainability relationship.

Focusing on the entire period 2000 to 2019, the average annual publications growth rate of papers on sustainability is only about 1%. From 2015 to 2019, the average annual publications growth rate on the topic of sustainability increased to 4.6%, while the topic of norm–sustainability records the average annual publications growth rate of 4.1%.

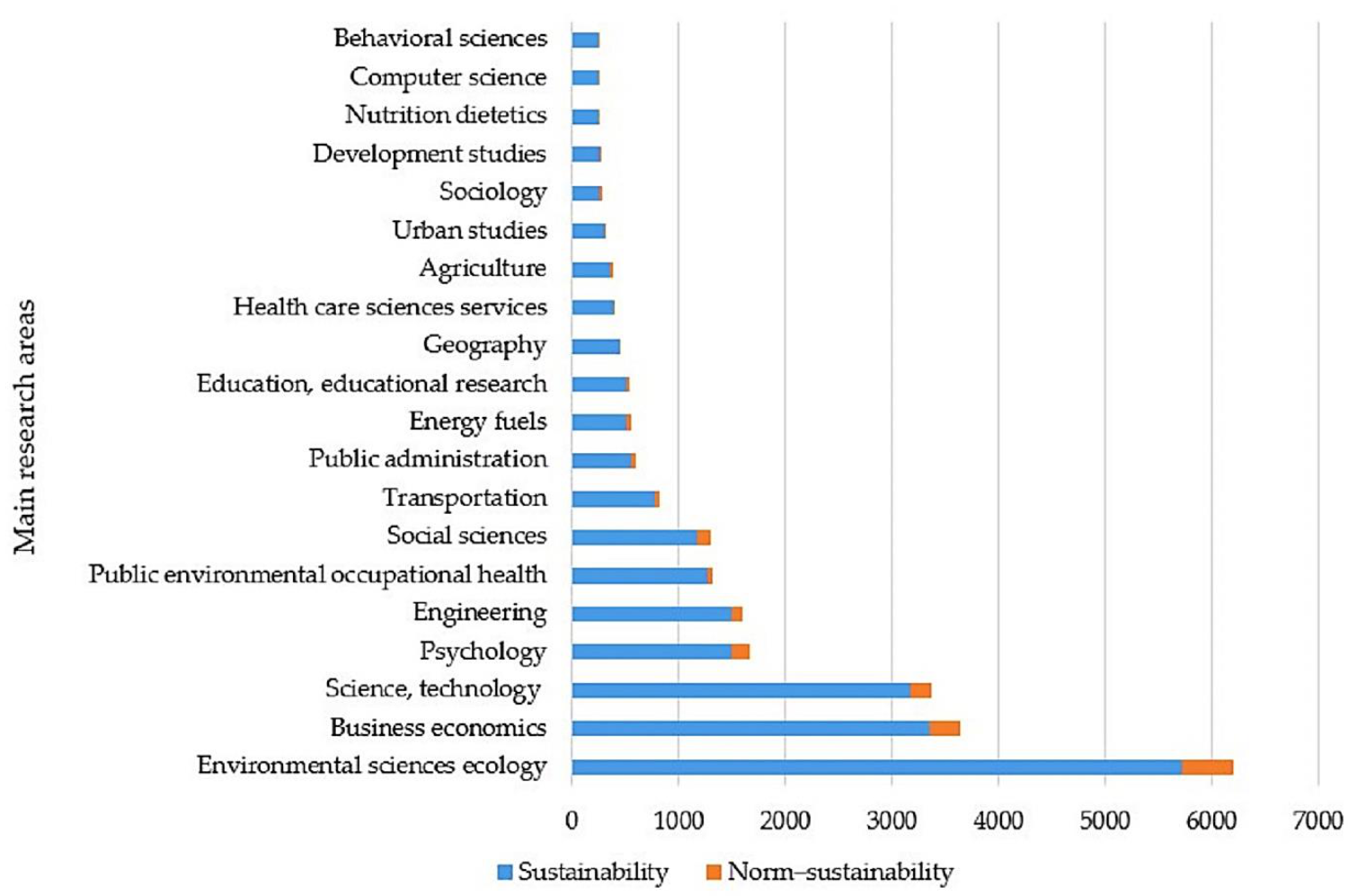

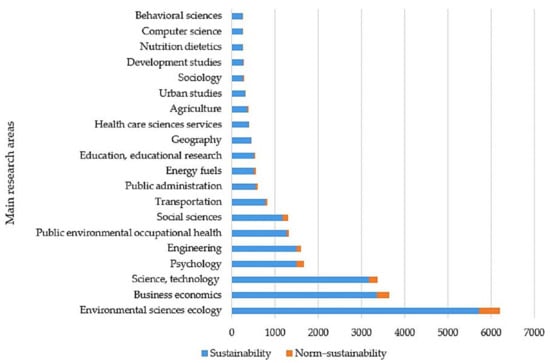

Based on our Web of Science search results, Figure 2 presents the ten most popular research areas on pro-environmental sustainability in general and on the link between social norms and pro-environmental sustainability in particular. As presented in Figure 2, only a small fraction of papers on pro-environmental sustainability focus on the impact of social norms on pro-environmental sustainability. The majority of topics revolve around environmental sciences and ecology, business, economics, science and technology, psychology, engineering, public environmental occupational health and social sciences.

Figure 2.

Number of publications within the 10 main research areas in the pro-environmental sustainability field.

Based on our Web of Science results, we identified the top journals and authors publishing on the topic of pro-environmental sustainability (see Table 2). Of the top 20 journals in terms of the number of publications on pro-environmental sustainability, two show an impact factor above 6 ([24]; Journal Impact Factor (JIF 2019)): Resources, Conservation and Recycling and Journal of Cleaner Production.

Table 2.

Top 20 journals and top 10 authors in pro-environmental sustainability.

Of the top 10 most published authors on pro-environmental sustainability, all publish in Sustainability and eight in the Journal of Cleaner Production (see Table 2). With no fewer than 58 publications on sustainability, Han has been the leading author in the first 20 years of this century. Of his papers, 19 have dealt with social norms.

4. Research Development on the Relationship between Social Norms and Sustainability

Focusing specifically on social norms and sustainability, the top journals publishing such research are largely the same as those publishing work on sustainability in general (see Table 3). Sustainability again leads with respect to the number of publications, whereas the Journal of Environmental Psychology heads the list in terms of the number of citations. Table 4 provides the information on the journal impact factor ([24]; Journal Impact Factor (JIF 2019)) of the top 10 journals publishing on norm–sustainability and lists the top 10 authors on the norm–sustainability topic.

Table 3.

Top 10 journals publishing papers on norm–sustainability in the past 20 years.

Table 4.

Top 10 journals and top 10 authors in norm–sustainability.

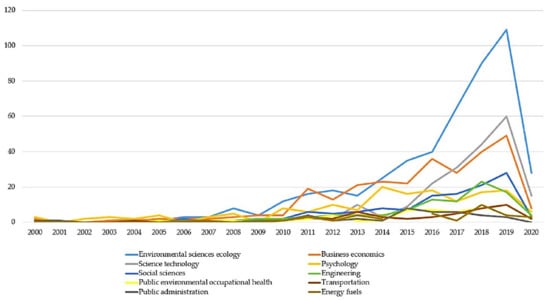

With 19 publications, Han has been the leading author on norm–sustainability in the first 20 years of this century. While the remaining authors on the list mainly published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology, Sustainability and Business Strategy and the Environment, note that in this context Font does not have any publications in the top 10 journals publishing on norm–sustainability. His work focuses on tourism and hospitality management (research discipline of social sciences, see Figure 3), a research area in which the interest in the topic of norm–sustainability is slowly growing.

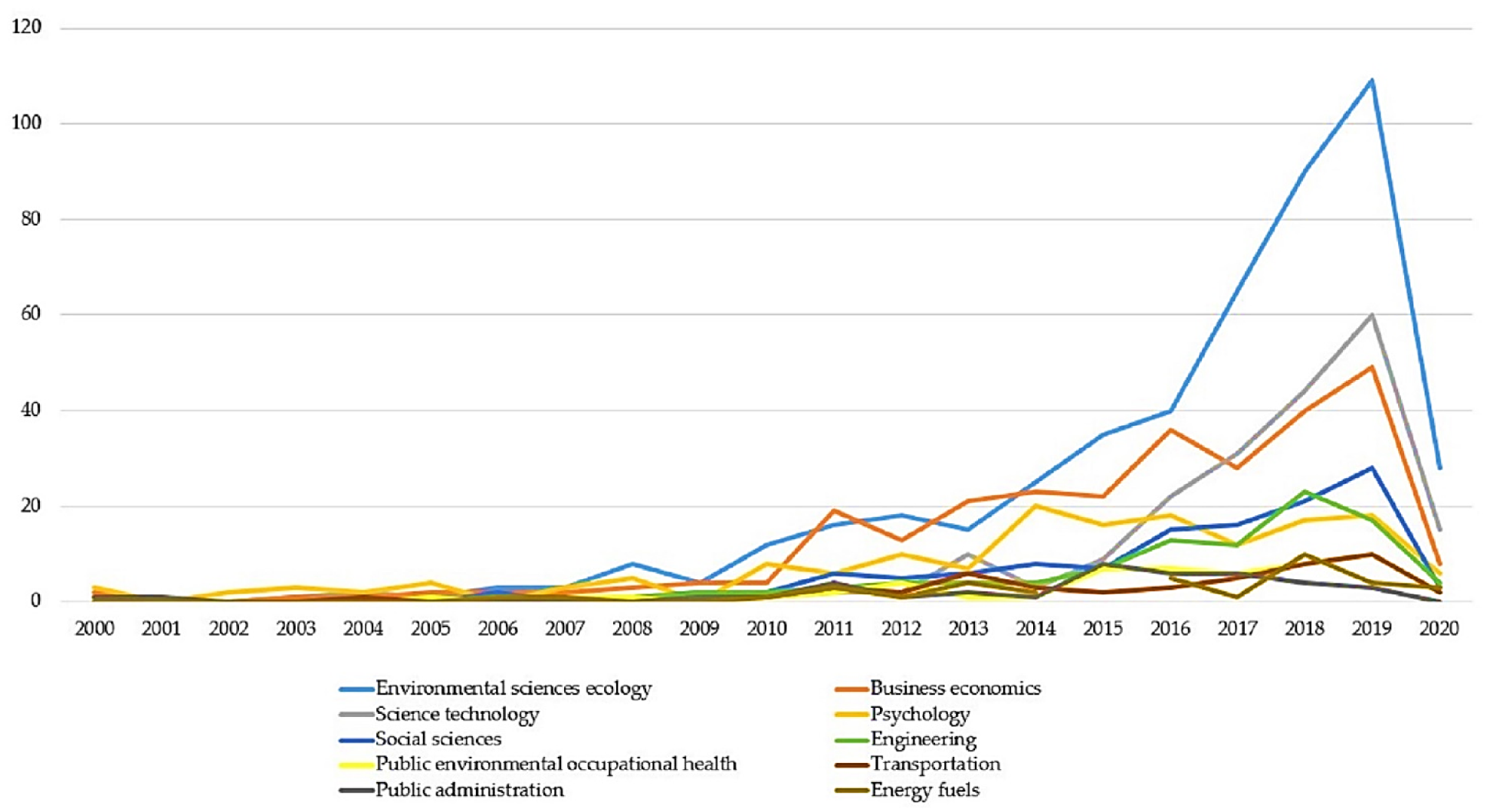

Figure 3.

Popularity of norm–sustainability topics across different research disciplines over time.

Figure 3 shows the evolving interest in norm–sustainability within the ten most popular research areas. The development of the individual research topics mirrors the general pattern of sustainability research identified before. After a relatively low level of research activity in the first ten years of this century, interest in most topics increased noticeably during the past five years. The topic of norm–sustainability is most popular in the area of environmental sciences ecology. Business economics, one of the areas of particular interest to us, is the third most popular research discipline in terms of papers dealing with norm–sustainability.

Taken collectively, the findings of the systematic literature review provide a comprehensive summary of the research on the norm–sustainability relationship developed during the last 20 years. Our analysis indicates that the interest in the norm–sustainability relationship has increased substantially in the last decade. This is in line with research on sustainability in general. Among the journals publishing in the field, Sustainability is by far the most important outlet. Sustainability publishes more than double the number of papers on the norm–sustainability relationship than any other journal. Norm–sustainability has been discussed in a wide range of contexts, from environmental sciences ecology to public administration. The most prolific authors on norm–sustainability have been Han and Klockner. Their work focused mainly on social sciences. In terms of our focal interest, norm–sustainability and consumer behavior, only a relatively small number of contributions could be identified. These contributions focus primarily on business economics.

5. Research on the Role of Self-Construal and Culture in the Norm–Sustainability Relationship

Turning to our second research question, namely to what extent previous work has taken account of our focal moderators, self-construal and culture, we conducted a more detailed analysis of the papers that broached these topics. As previously mentioned, our Web of Science analysis indicated that out of 1048 papers addressing the relationship between social norms and sustainability, only twenty incorporate both culture and self-construal when researching this norm–sustainability relationship (see Table 1). Considering that these papers appear in both categories (i.e., self-construal in norm–sustainability and culture in norm–sustainability relationship), there are 111 additional papers dealing with self-construal only, and an additional 136 papers that refer to the cultural context only. For these 267 papers, we conducted a more detailed analysis of the abstracts to gain a better understanding of their research focus.

The topic of norm–sustainability in these papers is present in a variety of research areas, the leading being environmental science and ecology, with 118 publications. As our research interest lies in consumer behavior, we are primarily interested in business economics, psychology, social sciences and sociology. However, we analyzed publications in the top 10 research areas listed below to be sure that we did not omit something of importance to our study.

Of the 267 papers including self-construal and/or culture in the norm–sustainability relationship, 245 are present in Table 5, while 22 papers (i.e., 267–245) fall outside the top 10 research areas on our list. Of the remaining 245 papers, 59 appear in more than one research area. Our main interest areas, i.e., business economics, psychology, social sciences and sociology, are all present in the list. With 66 publications, business economics is the second most popular area for work on norm–sustainability.

Table 5.

Main research areas for 245 papers on norm–sustainability.

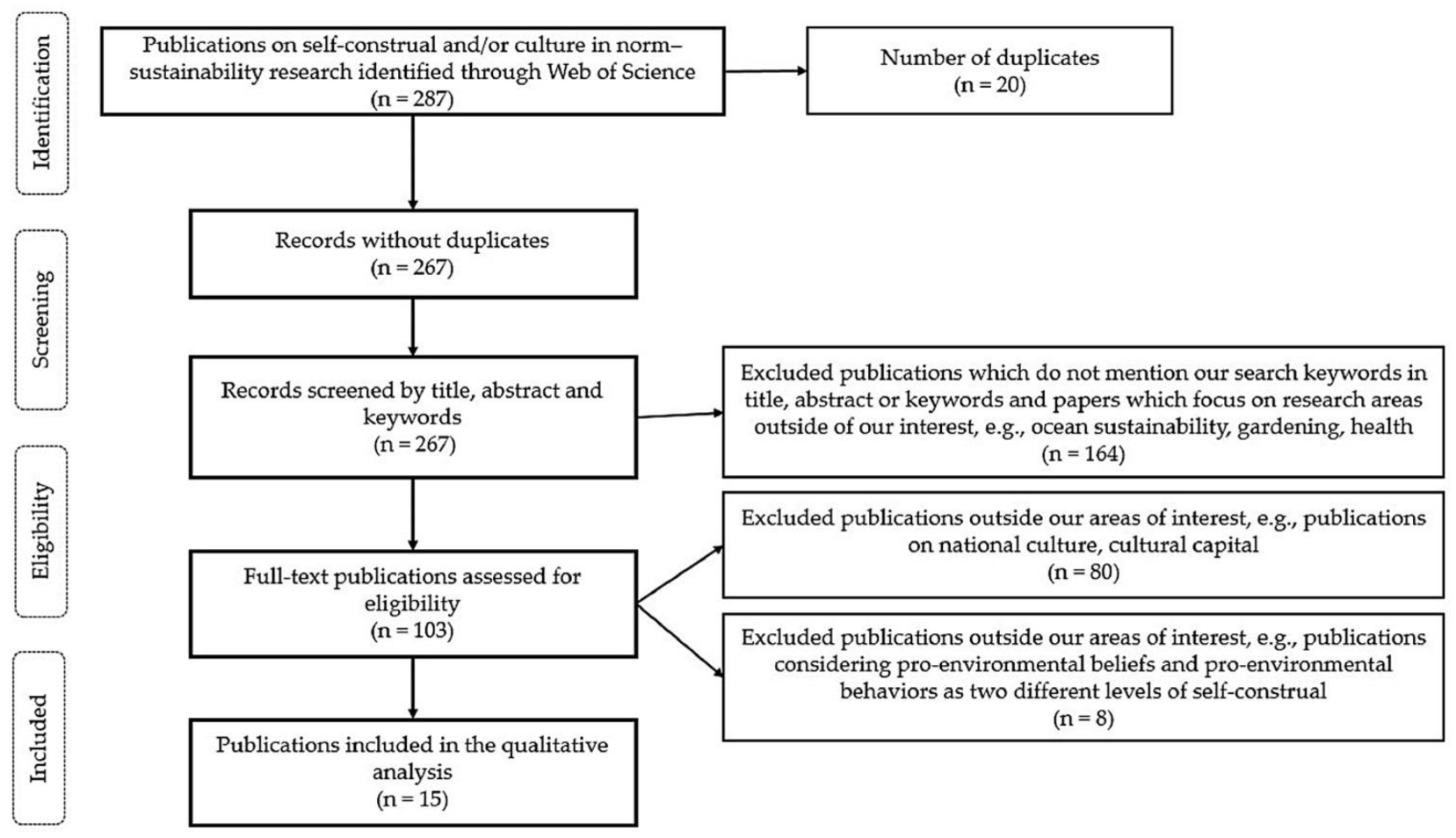

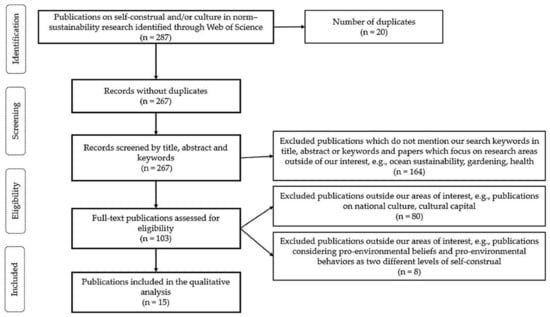

Next, we removed from further analysis all papers that fell outside our focus on sustainable consumer behavior. Table 5 provides a list of topics within each research area, enabling us to identify those that were not of interest for our study, from ocean sustainability to gardening, health, religion and others. On this basis, we excluded 164 papers and continued by reading the remaining 103, analyzing whether they dealt with individualism and collectivism on a cultural and/or self-construal level in the norm–sustainability relationship. Papers on topics such as national culture (e.g., [25,26]) or cultural capital (e.g., [27]) were removed at this stage because they were not relevant to our research focus on consumer behavior. This resulted in the exclusion of another 80 papers.

We continued with an in-depth analysis of the remaining 23 papers. At this stage, we removed eight more papers from further analysis. For instance, the study of Yan et al. [28] does not address the norm–sustainability relationship but only briefly mentions norms as a factor of ethnic diversity that may influence individuals’ decision making about water. Further, the authors (i.e., [28]) focus on cultural impacts on sustainable behavior, taking a general approach on culture, while Bertoldo et al. [29] look at pro-environmental beliefs and pro-environmental behaviors as two different levels of self-construal. The entire stepwise selection process, depicted in Figure 4, resulted in a final dataset of 15 papers.

Figure 4.

Data extraction process.

In summary, the analyses pertaining to our second research question, namely to what extent previous work has taken account of culture and self-construal in norm–sustainability, revealed only 15 papers that focused on the role of self-construal and culture in this relationship. While a larger number of papers mentioned the general importance of culture and/or self-construal, they did not analyze their effect on the norm–sustainability relationship and, consequently, had to be excluded from further scrutiny. All of the remaining 15 papers on our final list for analysis incorporate individualism and/or collectivism on a cultural and/or self-construal level. Next, we analyzed the content of the remaining papers in detail.

6. Methodological and Theoretical Fabric of the Research on the Role of Self-Construal and Culture in the Norm–Sustainability Relationship

For the purpose of appraising and synthesizing the remaining 15 papers, we conducted several qualitative analyses using NVivo 12. Table 6 lists the papers included in our qualitative analysis by year of publication, ranging from 2012 to 2020.

Table 6.

Final list of papers for analysis by year of publication.

In the next step, we analyzed in which context the listed papers mention sustainable behavior, norms, culture and self-construal. Table 7 presents a detailed visualization of this analysis. The most popular type of sustainable consumer behavior among the papers is sustainable consumption, including purchase of organic products [18], smart energy devices [38], sustainable holiday choices [19] and other types of green purchase (e.g., [30,32,34]. Other kinds of sustainable behavior referred to in the papers include recycling (e.g., [20,21]), littering [20] and grasscycling and composting [12].

Table 7.

Key constructs of the analyzed papers.

Table 7 provides an overview of the context in which our focal papers mention norms, culture and self-construal. While we can notice that all listed papers refer to social norms, either in general (e.g., [19,21,30,32]) or by mentioning descriptive and injunctive norms (e.g., [1,12,33]), we can also observe some differences in their research design. For instance, in their study, Mintz et al. [21] mention social norms in general but refer to both cultural dimensions (i.e., individualism and collectivism). Although Soyez [30], Onwezen et al. [18] and Hardeman et al. [19] look at self-construal and culture in norm–sustainability, there are some differences in their approach. While all three papers mention individualism and collectivism at the self-construal level, Soyez [30] and Onwezen et al. [18] focus on individualism and collectivism as well, while Hardeman et al. [19] focus exclusively on individualism. Furthermore, Onwezen et al. [18] analyze descriptive norms, whereas Soyez [30] and Hardeman et al. [19] examine social norms in general. While subjective norms are mentioned in Soyez [30], Hardeman et al. [19] mention personal norms.

At the next stage, we analyzed the content of the listed papers and noticed that some papers use the terms “individual” and “collective” self for independent and interdependent self-construal (e.g., [19]). Although Mingolla et al. [38] do mention injunctive norms, their research focus lies on descriptive norms only. In addition, there are two other papers that refer to descriptive norms exclusively and mention injunctive norms only in the limitations (i.e., [18]) or discussion section of their papers (i.e., [20]). We further identified green/sustainable purchase (e.g., purchase of organic products, purchase of smart energy devices), grasscycling, composting, lettering and recycling as the common types of sustainable behavior analyzed in the listed papers.

Given the differences in the research design of our focal papers, the key insights, which can be distilled, are somewhat contradictory. For instance, some authors (e.g., [18,33]) concluded that sustainable consumer behavior of individuals from collectivistic cultures is more influenced by social norms compared to the individuals from individualistic cultures, whose sustainable consumer behavior results mainly from their attitudes. Further, Park et al. [20] demonstrated that normative effect varies across cultures and that the individuals from high-context cultures are more willing to comply with social norms than the ones from low-context cultures. In contrast, some authors (e.g., [1,21]) demonstrated that norm compliance does not depend on country differences. For example, in contrast to their expectations that social norms are a stronger predictor of household waste management in Japan than in Israel and Germany, Mintz et al. [21] identified a stronger influence of social norms on easy recycling among individuals from Israel than among the ones from Japan. Furthermore, in contrast to findings in other studies (e.g., [39,40]), Nguyen et al. [32] did not find a significant relationship between cultural dimensions (individualism, collectivism, long-term orientation) and environmental concern.

The moderating effect of self-construal in norm–sustainability remains unclear. While some authors (e.g., [18]) concluded that the effects of attitudes and social norms on pro-environmental behavior depend on the activated level of self-construal (i.e., independent vs. interdependent), others (e.g., [19,38]) demonstrated norm compliance irrespective of the activated level of self-construal. Furthermore, Mingolla et al. [38] did not find a significant interaction between the effect of descriptive norms and activated self-construal.

There are also other discrepancies. For example, Gifford and Nilsson [31] found that injunctive norms can eliminate the possible negative effect of descriptive norms in an individualistic country, such as the U.S., while Han [33] did not support the notion that injunctive norms are a significant predictor of sustainable behavior in the U.S. Table 8 provides an overview of the key differences in findings of our focal list of papers and proposes some topics for deeper investigation in the future.

Table 8.

Key insights of our focal list of papers and propositions for further research.

Next, we identified methodological differences in the identified papers, i.e., whether they are empirical (qualitative or quantitative) or conceptual. With only two conceptual papers on the list, Table 9 shows that the main thrust of our focal papers lies in empirical research. While the studies are mostly quantitative, White and Simpson [12] and Hardeman et al. [19] applied mixed methods in their research (i.e., both qualitative and quantitative).

Table 9.

Methodological differences in our focal list of papers.

Whenever culture is analyzed, the selection of country assumes importance. Table 10 lists the countries addressed in the studies we identified. Overall, 17 countries were researched in 11 papers. Onwezen et al. [18] included nine countries and Soyez [30] five, while other papers focused on three or fewer countries. Of all researched countries, the United States is the most popular (five papers), followed by Germany (four papers).

Table 10.

Countries studied in our focal list of papers.

The United States is also the most individualistic nation researched in the analyzed papers, scoring 91 on Hofstede’s cultural dimensions [41]. Other highly individualistic countries on the list are Australia (90), United Kingdom (89), Netherlands (80) and Canada (80). The least individualistic countries are South Korea, with a score of 18 on Hofstede’s dimension, as well as China (20), Singapore (20) and Vietnam (20). Thus, most research had taken place in individualistic cultures and only three studies included countries with relatively low individualism scores. Of these three studies, only the one conducted by Onwezen et al. [18] included countries with high and low individualism scores, whereas the other two studies focused on one country only, namely Vietnam [32] and China [34]. This clearly indicates a dearth of research on collective cultures in general and on comparisons between individualistic and collective cultures in particular.

Finally, we identified all the theories referred to in our 15 papers (Table 11). In total, 13 different theories are mentioned, with Soyez [30] referring to five of them in her study. The most frequently referenced theory is the Theory of Planned Behavior, which is mentioned in nine papers (e.g., [30,34,37]). Other popular theories are the Theory of Reasoned Action (e.g., [20]), Norm-Activation Theory (e.g., [31]) and Social Identity Theory (e.g., [12]), mentioned by three papers each. We also noticed how some theories are used in conjunction. For instance, Soyez [30], Gifford and Nilsson [31] and Iran et al. [36] all mentioned the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Norm-Activation Theory in their study, while the papers of White and Simpson [12] and Mingolla [38] both mentioned the Social Identity Theory and the Self-Construal Theory (e.g., [15] in [12]). The papers of Onwezen et al. [18] and Iran et al. [36] both use the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action.

Table 11.

Theories mentioned in our focal list of papers.

Drawing together the insights gained on our third research question, namely the methodological and theoretical fabric of the research on the moderating role of self-construal and culture, we conclude that in terms of content, the authors mostly focus on one of the dimensions of either culture (individualistic or collectivistic), self-construal (independent or interdependent) or social norms (descriptive or injunctive). In the following discussion, we outline the conclusions that can be drawn from the analyzed literature and suggest future research avenues to derive a more comprehensive understanding of the self-construal and culture in the norm–sustainability relationship.

7. Discussion and Suggestions for Future Research

Our research started with a broad review of 16,000 papers on pro-environmental behavior published over the previous 20 years. While the results indicate a rising interest in this field, papers focusing on the topic of norm–sustainability account only for a small fraction of papers on pro-environmental sustainability. Our analysis identified only relatively few papers that considered culture and/or self-construal in the norm–sustainability relationship, while the majority of papers had to be excluded from further analysis because they did not deal with individualism and collectivism on a cultural and/or self-construal level in the norm–sustainability relationship.

There are considerable dissonances in the findings reported in our focal list of 15 papers in terms of the influence of culture and self-construal in norm–sustainability. For instance, some authors (e.g., [18,32,36]) concluded that cultural differences can influence social norms and sustainable behavior, while others confirmed the influence of culture only in collectivistic countries, where people have been found to be more susceptible to normative social influences (e.g., [20,21,30,33,35]). Regarding self-construal, descriptive norms appear to influence sustainable consumer behavior when both individual and collective levels of the self are activated (e.g., [12,19,38]). When the collective self is activated, both descriptive and injunctive norms are more salient, while at the individual level of the self, descriptive norms are more compelling than injunctive norms [12].

Looking in detail at the content and context of papers in our final list, we noticed that researchers tend to focus more on descriptive norms than injunctive norms (e.g., [18,20]). A considerable number of papers looked at social norms in general (e.g., [30,35]), while some also mentioned subjective (e.g., [31,33]) and personal norms (e.g., [37]). Differences in research focus are also noticeable with respect to culture. While the majority of the identified papers considered both individualism and collectivism as cultural dimensions, Hardeman et al. [19] only conducted their research in an individualistic culture (i.e., the Netherlands). Along with individualism/collectivism, some authors also incorporated other cultural dimensions in their research, including long-term orientation [32], power distance, uncertainty avoidance and masculinity/femininity [36]. When including self-construal in their studies, the authors in our focal list addressed the dimensions of independent and interdependent self, and we noticed that some referred to these dimensions as “individual” and “collective” self (e.g., [12]). The majority of papers focused on sustainable consumption as one type of sustainable consumer behavior. In sum, this suggests a need for further research, particular on injunctive norms and collectivistic cultures.

Considering the whole topic of moderating effects of self-construal and culture in norm–sustainability, differences in research focus became obvious. For instance, Soyez [30] and Onwezen et al. [18] considered individualism and collectivism in a cultural and self-construal context but pursued a different focus with respect to norms. Soyez [30] looked at subjective norms and social norms in general, while Onwezen et al. [18] focused on descriptive norms only. Similarly, Hardeman et al. [19] referred to both independent and interdependent self but only to one cultural dimension (i.e., individualism) in relation to personal and social norms in general. Furthermore, Culiberg and Elgaaied-Gambier [1] considered culture in general with respect to injunctive, descriptive and pro-environmental norms, while Iran et al. [36] focused their research on four different cultural dimensions in norm–sustainability but looked at social norms in general. Once again, these differences point to a need for a more systematic research on the moderating effect of culture and self-construal in the norm–sustainability relationship.

We notice that the authors mostly focus on one of the dimensions of either culture (individualistic or collectivistic), self-construal (independent or interdependent) or social norms (descriptive or injunctive) and believe that this may be one of the reasons for the rather contradictory findings on the moderating effects of culture and self-construal in norm–sustainability. In terms of research setting, we identified a lack of comparative research between individual and collective cultures. With regard to methods and theories, we noted that the large majority of papers are empirical and that the research is based on a wide variety of theories. Given the heterogeneity in research settings and theoretical foundations, it is not surprising that a comprehensive understanding of the role of self-construal and culture in the norm–sustainability relationship is still missing.

Taken collectively, our analysis offers important contributions to theory, public policy and practice as well as some potentially fruitful research avenues.

In terms of theory, we contribute to a deeper understanding of how and why social norms affect sustainable consumer behavior, and we identify the importance of closer attention to culture and self-construal as moderators in this relationship. In particular, we contribute to extant research by highlighting the effectiveness of descriptive norm compliance to sustainable behavior when both individual and collective self are activated, while at the collective level of the self, injunctive norms also influence sustainable behavior (e.g., [12,19,38]). Furthermore, we identify that people in collectivistic cultures show norm compliance regarding sustainable behavior, whereas the influence of injunctive and descriptive norms on pro-environmental behavior of people from different individualistic cultures appears to differ depending on the specific individualistic country (e.g., [20,21,30,33].

In terms of public policy, our paper suggests that policy-makers should tailor their communication policy to reflect country-specific differences, as the effects of descriptive and injunctive norms on pro-environmental behavior depend on cultural factors (e.g., [1,20,34]). A personal approach, such as adaptation to specific cultural segments, may be of particular importance for encouraging sustainable behavior in individualistic cultures, whereas a more standardized approach may be applicable to collective cultures. Policy-makers are especially encouraged to utilize descriptive norms in promoting sustainability practices, as these are influential on pro-environmental behavior by both independent and interdependent consumers.

Similarly, from a managerial perspective, our research demonstrates the importance for marketers to adapt their marketing messages across countries and cultures through combining injunctive/descriptive norms and individual/collective self (e.g., [1,19,32,35]). Hence, when it comes to sustainable products and services, it is advisable to approach each culture as unique. Adapting marketing strategy to specific cultural segments may be more important for marketers than focusing on standardization. For instance, targeting highly independent consumers with injunctive messages calls for strategies affirming the consumer’s autonomy, either through marketing messages or by encouraging consumers to claim their autonomy [12]. Further, some authors suggest that managers should put ‘social pressure’ on their customers via social networks and promote collectivistic values (e.g., [35]). Mingolla et al. [38] proposed that managers could improve the credibility of their communication by emphasizing wherever possible the adoption of their sustainable products by significant numbers or proportions of people. Park et al. [20] proposed social marketing campaigns highlighting collective values (i.e., acceptance, affiliation and community).

Finally, in terms of future research avenues, there is a general need for a deeper investigation of cultural factors affecting the influence of social norms on pro-environmental behavior in order to resolve some of the observed differences in the reported findings. More specifically, researchers may want to investigate the underlying processes of relatively negative responses to benefit appeals when the collective level of the self is activated. Second, researchers could consider looking at the differing effects of injunctive and descriptive norms in the self-regulatory function of anticipated pride and guilt between collectivistic and individualistic cultures. Future research could also explore underlying reasons for why highly independent individuals demonstrate norm compliance or explore whether the effectiveness of norm appeal is related to quality perceptions for highly independent individuals. Lastly, a puzzling aspect of our findings is the contradictory results of the effects of social norms on pro-environmental behavior between and within individualistic countries. Hence, a closer investigation of these contradictions would be beneficial. Any future research should ideally incorporate both dimensions of self-construal (i.e., individualism and collectivism) and social norms (i.e., descriptive and injunctive) when inspecting the different impact these construal levels have on the effects of descriptive and injunctive norms on pro-sustainability. The research directions we proposed would improve our theoretical understanding of the moderating roles of culture and self-construal in the norm–sustainability relationship and should also be of value for policy-makers and managers who want to encourage the use of sustainable products and/or services in different countries.

8. Limitations

Our paper does not come without limitations. Although we reviewed a considerable number of papers, as we only used Web of Science as our data source, we may have omitted some papers from our study. Furthermore, although we reviewed all papers with respect to the same criteria, some papers address a number of issues, and we cannot be sure that we did not exclude a relevant piece of research from our analysis when focusing only on the information presented in abstracts. Finally, we reviewed only papers written in English, which may inevitably lead to the omission of some findings.

In spite of these limitations, we hope that our paper contributes to a better understanding of the literature on pro-environmental behavior and will motivate new in-depth research on the moderators between social norms and sustainable behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B.S. and S.S.; data curation, S.S.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, S.S.; methodology, B.B.S. and S.S.; software, S.S.; visualization, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, B.B.S. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Culiberg, B.; Elgaaied-Gambier, L. Going green to fit in—Understanding the impact of social norms on pro-environmental behaviour, a cross-cultural approach. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 40, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostadinova, E. Sustainable consumer behavior: Literature overview. Econ. Altern. 2016, 2, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ryoo, Y.; Hyun, N.K.; Sung, Y. The effect of descriptive norms and construal level on consumers’ sustainable behaviors. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 536–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Bohlen, G.M. Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, V.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. How techniques of neutralization legitimize norm- and attitude-inconsistent consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A.; Reno, R.R. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Personal Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A room with a viewpoint: Using social norms to motivate environmental conservation in hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reno, R.R.; Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A. The transsituational influence of social norms. J. Personal Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W.P.; Nolan, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J.; Griskevicius, V. The constructive, destructive, and reconstructive power of social norms. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. The ethical consumer. Moral norms and packaging choice. J. Consum. Policy 1999, 22, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Social norms and cooperation in real-life social dilemmas. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Simpson, B. When do (and don’t) normative appeals influence sustainable consumer behaviors? J. Mark. 2013, 77, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, H.L. Perspectives on Social Order, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. 1–658. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A.; Reno, R.R. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 24, 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Singelis, T.M. The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personal Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.; Xie, X.; Liu, C. Interdependent orientations increase pro-environmental preferences when facing self-interest conflicts: The mediating role of self-control. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 46, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values, 1st ed.; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1980; pp. 1–328. [Google Scholar]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bartels, J.; Antonides, G. Environmentally friendly consumer choices: Cultural differences in the self-regulatory function of anticipated pride and guilt. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardeman, G.; Font, X.; Nawijn, J. The power of persuasive communication to influence sustainable holiday choices appealing to self-benefits and norms. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Ulusoy, E.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, H.E. Temporal distance and descriptive norms on environmental behaviors: A cross-cultural examination of construal-level theory. Sage Open 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, K.K.; Henn, L.; Park, J.; Kurman, J. What predicts household waste management behaviors? Culture and type of behavior as moderators. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 145, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A.; Papaioannou, D.; Sutton, A. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review, 1st ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- Bungsa Bangsa, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B. Linking sustainable product attributes and consumer decision-making: Insights from a systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InCites Journal Citation Reports, Clarivate Analytics. Available online: https://jcr.clarivate.com/JCRLandingPageAction.action (accessed on 24 June 2020).

- Cordano, M.; Welcomer, S.; Scherer, R.; Pradenas, L.; Parada, V. Understanding cultural differences in the antecedents of pro-environmental behavior: A comparative analysis of business students in the United States and Chile. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 41, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.K.; Chandra, B. An application of theory of planned behavior to predict young Indian consumers’ green hotel visit intention. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agovino, M.; Crociata, A.; Quagoline, D.; Sacco, P.; Sarra, A. Good taste tastes good. Cultural capital as a determinant of organic food purchase by Italian consumers: Evidence and policy implications. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 141, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; McManus, P.; Duncan, E. Understanding ethnic differences in perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours: A study of domestic water use in Sydney. Geogr. Res. 2018, 56, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldo, R.; Castro, P.; Bousfiels, A.B. Pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors: Two levels of response to environmental social norms. Rev. Latinoam. De Psicol. 2013, 45, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyez, K. How national cultural values affect pro-environmental consumer behavior. Int. Mark. Rev. 2012, 29, 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behavior: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Greenland, S. The influence of cultural values on green purchase behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2017, 35, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.I. Determinants of organic cotton apparel purchase: A comparison of young consumers in the USA and South Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.L.; Qian, L.X.; Singhapakdi, A. Sharing sustainability how values and ethics matter in consumers’ adoption of public bicycle-sharing scheme. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Kim, M. Hofstede’s collectivistic values and sustainable growth of online group buying. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iran, S.; Geiger, S.M.; Schrader, U. Collaborative fashion consumption—A cross-cultural study between Tehran and Berlin. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingolla, C.; Hudders, L.; Cauberghe, V. Framing descriptive norms as self-benefit versus environmental benefit: Self-construal’s moderating impact in promoting smart energy devices. Sustainability 2020, 12, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.M. Antecedents of green purchase behavior: An examination of collectivism, environmental concern, and PCE. Adv. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede Insights, Compare Countries. Available online: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/product/compare-countries/ (accessed on 22 July 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).