1. Introduction

Identifying a sustainable link between economic growth and societal well-being is a challenge in itself, especially in areas that are driven by strong local traditions and culture [

1,

2]. For this reason, voluntary territorial certification is a way to improve the competitiveness of a destination while at the same time communicating and preserving local values. An example of such a fast-growing voluntary territorial certification is Cittaslow [

3].

The slow trend is another international offer of cooperation between cities regarding exchanging and implementing good practices to promote the improvement of the quality of life of residents [

4,

5]. Cittaslow as a movement dates back to 1998. The association is based in Orvieto, in the Italian region of Umbria. Italian cities have become a model for other European and then world cities. Ultimately, an international movement was established to improve the quality of life of its inhabitants, to celebrate a “slow” and healthy lifestyle, and to protect the natural and cultural environment of small towns [

6,

7]. Similar to Italy, a country that initiated the movement, it is joined by cities promoting their history, culture and traditions.

The Cittaslow City Network is an international organization associating approximately 260 cities in 30 countries, of which 34 are Polish cities. In Poland, this trend was initiated in 2006 by four founding cities from the Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodeship, including Reszel, Biskupiec, Bisztynek and Lidzbark Warmiński. Currently, 24 cities in the region belong to the movement. The slow movement opposes the fast-living culture, and the main premise of this idea is to achieve balance throughout our lives [

8]. The concept of the functioning of the population in a leisurely manner can manifest itself in various areas. Its influences are noticed in ever wider aspects of community life, in the way of consumption, travel, work, production, education or functioning of cities, among others [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. A key aspect of Cittaslow membership is the promotion of the town, which aims to show that a small town is a favorable place to live due to its proximity to nature, products of high quality and strong local communities [

8]. The dissemination of the Cittaslow network can be seen as an expression of the need to seek new incentives for economic development [

9]. Its purpose is to meet the needs of local communities, as well as to attract people to cities, ensuring the development of the city and improving the living conditions of the population [

14]. We are observing interest in the Cittaslow movement as society and, in particular, city inhabitants are becoming increasingly more aware of existing threats and at the same time more and more demanding when it comes to living standards. This is manifested in the search and pursuit of a new “different lifestyle” [

11].

The Cittaslow network functions as an association that is open to cities with a population of 50,000 or less. In order to join the network, a town has to undergo a certification process, which is an assessment carried out in seven areas: Energy and environmental policy, infrastructure policies, quality of urban life policies, agricultural, tourism and artisan policies, policies for hospitality, awareness and training, social cohesion, partnerships, which are assessed through 72 specific requirements. To gain access to the Cittaslow network, a city has to pass the assessment with at least 50% + 1 of the requirements. The same catalog of requirements is also used during the subsequent assessment (the so-called Recertification), which cities undergo five years after joining the network [

15]. The entity responsible for the implementation of the concept is the local government. The initiatives undertaken by this entity are crucial to the city’s development opportunities. It is therefore important that they are adequate to the needs of residents.

An important argument for the involvement of local authorities in the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship in favor of participation in the movement is the path of focusing on pro-social and pro-environmental activities, caring for the preservation of the unique character of cities, paying special attention to the need for monuments restoration, promoting local manufacturing and local cuisine, and in the case of municipalities oriented toward the development of tourism, also caring for the traditions of hospitality [

16]. The Cittaslow idea is increasingly recognized by specialists as a new proposal to stimulate local development aimed at preserving valuable local values [

17,

18]. It is a response to contemporary challenges in the age of globalization [

19,

20,

21]. With regard to the proposal to stimulate local sustainable development, development itself should be understood here as a socioeconomic process manifesting itself in the modification of the economic structure, as well as improving the living conditions of the population. According to Winiarski [

22] among others, development is a component of two other, narrower concepts of economic growth and social growth. Socioeconomic development can be considered on different scales, but it is mainly on the regional and local scales where own human resources (of the region, commune, city) are an important factor in stimulating beneficial changes [

23].

Innovative ways of city organization such as the Cittaslow movement are focused on promoting a model of peaceful pace of life, which should not hinder continuous and thoughtful development [

24,

25,

26].

Participation in the movement obliges local authorities to initiate and implement such economic programs that take into account the principles of the idea of sustainable development [

10,

13,

20,

27].

In this context, development means a sustainable increase in economic potential, competitive strength, and the level and quality of life of the inhabitants, i.e., all those elements that contribute to the development of local communities. These communities, in turn, owing to the implemented Cittaslow principles, can become small homelands for the inhabitants, capable of satisfying emerging needs [

26,

28,

29].

For highly organized societies, there remains an important issue of the institutionalization of communities of inhabitants of a given territory, which generates legal, social, and political effects experienced by its members. Therefore, following Kogut-Jaworska et al. [

30], it can be concluded that local development includes not only economic, political or cultural changes, but also processes in society, including changes in relations, institutions, groups and other types of social systems. The result of local development is the promotion and strengthening of entrepreneurship, the production of new products that will satisfy local demand. These local products, often having the character of products and services embedded in the local tradition, are covered by special programs increasing their value and protecting local events. The main element of promotion is hospitality, which is supposed to be promoted by local guides prepared for this function under special training. In addition, an international system of information and marking of tourist routes is being introduced, guidelines for the presentation of the tourist offer are being implemented, new infrastructural investments are being made, including the organization of car parks on the outskirts of the city, attention is also paid to an efficient website with information on the opening hours of city institutions, accommodation and catering facilities, as well as events organized in the city [

8,

24,

31].

All these initiatives and projects serve to create a positive impact of activities undertaken by the local government on the living conditions of the local community, including those indicated in the certification documentation regarding the joining of a city to the Cittaslow network. They concern such areas as energy and environmental policy, the state of infrastructure, the quality of urban life, the level of development of agriculture, tourism and crafts, hospitality, social awareness and raising qualifications, as well as social cohesion and partnership (The full list of criteria is contained in the Association’s Statutes available on the PKSMC website.

http://cittaslowpolska.pl/ (accessed on 3 November 2020)).

The growing popularity of the idea of sustainable development and slow-style living is conducive to the promotion of culture, improvement of the living standards of local communities [

10,

23], popularization of regional products and crafts [

8].

It is worth pointing out that European Union countries for many years have been involved in promoting and implementing a sustainable development policy. Rzeńca [

32] organized the list of documents, which draws particular attention to the need for local authorities to ensure equal access for residents to a safe life, healthy food and the environment, including, among others: 1992 City Card, European Charter Cities Towards Sustainability of 1994, the European Perspective on Spatial Development of 1999, the New Charter of Athens of 2003, or the Toledo Declaration adopted in 2010. It is worth emphasizing that sustainable development is the basis for the functioning of the Cittaslow movement [

11,

17,

27,

33]. A balanced aspect of development is based on the conscious creation of the relationship between socioeconomic development, care for the environment (especially natural), and the needs and their satisfaction, which in turn determines the quality of life [

34,

35]. This in turn is an important element of the Cittaslow idea.

In relation to cities, the basic factors of sustainable development are external factors, including those of a social nature, which may include, inter alia, the education system, migrations, organizations and associations, relations between the authorities and the society, as well as economic aspects covering legal aspects related to the operation of economic policy and its conduct, central government policy, assistance funds and supralocal government policy. Elements characterizing the ecological aspect of this group of factors are, in particular, ecological policy at the supralocal level, legal acts concerning the environment and its protection [

36,

37].

Due to the fact that the city is not a fully self-sufficient unit and also uses the resources of suburban communities, its sustainable development should be understood as the even and simultaneous development of all spheres of activity of residents. These include social, economic and environmental dimensions. Therefore, development must be conducted in a planned way, because it is based on relationships and creating connections among all areas of life.

New cities in different countries are joining the Cittaslow movement, treating their belonging to the movement as part of the promotion of the city [

18]. Cities that apply for membership declare that they will work on meeting qualification requirements such as creating people-friendly places. Cittaslow network cities agree to plan public spaces, develop transport infrastructure that will provide comfort and higher quality of life to residents and ensure accessibility for disabled and elderly people [

7].

Previous research on the affiliation of cities to the Cittaslow network has mainly focused on the impact on the economic [

26,

27,

38] and social spheres [

10,

14], management, promotion and cooperation of Cittaslow cities [

39] as well as identification of spatial and environmental effects [

40]. As it has been observed, many authors working on urban development focus on social and economic factors, neglecting the impact of membership of these cities in various institutions and structures, including the Cittaslow network. In Poland, the first studies date back to 2009. Cities in the Polish network are diverse not only in terms of population, but also in terms of population density, the labor market situation or level of socioeconomic development [

13,

41,

42]. This is one of the reasons for undertaking research related to their membership in the Cittaslow network, and also for undertaking further research. Proper recognition of the advantages and disadvantages of the Cittaslow network and the identified examples of good practices of slow cities can provide a model reference for assessing the possibility of including other cities in the network [

43].

The Slow City logo is used by the city as a synonym for good quality in its various promotional initiatives. It is therefore important to find out the opinion of the local community on the role and significance of the city’s participation in the Cittaslow movement as a factor initiating new activities with a positive impact on local development. It is particularly important to obtain an answer to the question of what extent the city residents identify with the Cittaslow idea and perceive benefits from the city’s participation in the network.

2. Materials and Methods

City of Lidzbark Warmiński, located in the central part of Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodeship, was chosen as the research area. The city was one of the first towns in the region to join the Cittaslow network in Poland in 2006. It is one of the larger cities of the Cittaslow network in Poland. Lidzbark Warmiński, similar to other towns belonging to the network, promotes a chosen aspect of its functioning that is characteristic only for this particular city. In the case of Lidzbark Warmiński it is history, hidden in the antique parts of the town. The town was founded in 14th century and became the capital of Warmian bishops.

The first survey was conducted in 2017 and was a pilot. However, the obtained results encouraged the survey to be conducted again in 2019 to observe the changes taking place in residents’ opinions. Therefore, the aim of the research conducted in 2017 and 2019 was to identify the impact of the Cittaslow concept on the initiation of activities with a positive impact on local development. Referring to the main objective of the research, the hypothesis was adopted that membership in the Cittaslow network has a positive impact on the local development of a city, as it is a source of new projects undertaken by the authorities that improve the quality of life of the inhabitants and, at the same time, are implemented with the participation of local communities. The empirical part of the research was based on the analysis of existing data and the method of diagnostic survey. Quantitative research using the questionnaire was carried at a two-year interval, in 2017 and 2019. The CAWI (Computer Assisted Web Interviews) technique was used to conduct the survey, consisting of placing the questionnaire on the website. This form was chosen because it allowed to reach a wider audience, which contributed to the diversity of responses and to obtaining the most objective and reliable conclusions. The CAWI method is an excellent tool for conducting research using the Internet. The method allows reliable data to be collected due to the possibility of allowing respondents to participate in a study at their own pace and at a time that is convenient for them. It is also possible to include multimedia materials and additional information (e.g., in the attached links). The method is characterized by a relatively short research implementation time in comparison to direct surveys (e.g., sent by post) and ensures anonymity. It also allows for targeted selection of the group of respondents [

44,

45]. However, the disadvantages of CAWI method are that it can only be targeted at people who have access to the Internet and there is a lack of knowledge of who actually fills in the survey [

44].

The decision to repeat the research in 2019 included the use of the same method, with the purpose of comparing opinions from the group of Lidzbark Warmiński residents who responded. From the 368 respondents, 100 were randomly selected who represented similar structures in terms of gender, age and education to the group that participated in the 2017 survey. Owing to this procedure, differences in respondents’ opinions related to the features of their social profile regarding the development of Lidzbark Warmiński since joining the network of cities of “good quality of life” have been eliminated. The questions focused on the selected spectrum of socioeconomic development, namely, the level of quality of life of residents and the effects of actions taken as part of membership in the network of “cities of good quality of life” in the context of local development.

In 2017, 100 respondents answered the survey. In 2019, the residents of Lidzbark Warmiński showed more activity with the survey, and as many as 368 return forms were obtained. In order for the results to be comparable, they were analyzed with the same group of respondents (number); age and gender structure were also important. Therefore, 100 out of 368 questionnaires were selected for further analyses, taking into account age and gender of the respondents.

3. Results

For the analysis of data, the statements of 100 respondents who were the first to complete the 2017 survey, 56% women and 44% men, were used. The age of the respondents was: 18–29 years—60%, 30–39 years—20%, 40–49 years—10%, 50 years and more—10%. In the group of respondents, 8% had basic vocational education, 42% secondary and 50% higher. In the research conducted in 2019, the survey was completed by 368 people, and from this group 100 questionnaires filled out by respondents of a similar age and education level to the 2017 group were deliberately selected.

Most survey participants, including 63% of respondents in 2017 and 68% in 2019, declared that they knew what the Cittaslow network of cities is. In order to take into account the opinions of all respondents participating in the study, including those who did not have the knowledge about the Cittaslow idea, the study participants were referred to a link where they could become familiar with the definition of the concept.

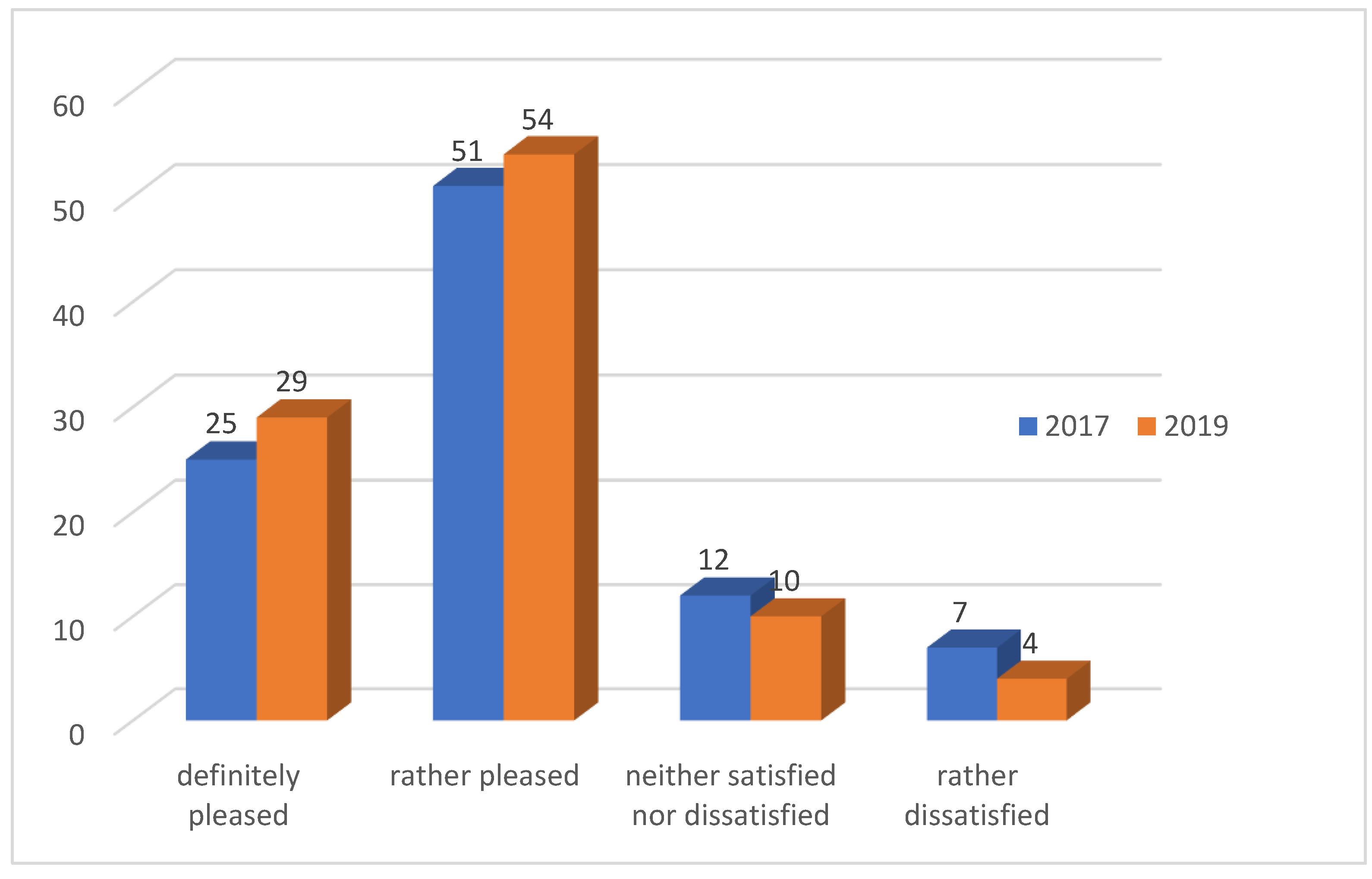

One of the key questions included in the survey questionnaire, to which respondents responded, concerned their subjective feelings in relation to the improvement of the level and quality of life of the inhabitants of Lidzbark Warmiński over the past five years. Distinguishing between categories of standard of living and quality of life is com-plex, and the categories adopted depended on the purpose of the proposed combinations. Bearing in mind the Cittaslow idea, the standard of living can be interpreted as the needs of ownership, and the quality of life concerns the needs related to emotional states. Many factors may influence the feelings of the local community regarding the level and quality of life in a city. The study showed that, in general, respondents rated their level of satisfaction with life in Lidzbark Warmiński highly. In 2017, a total of 76% of respondents said they were satisfied with the quality of life in the city, while in 2019 it was 83% of study participants (

Figure 1).

The city’s development is closely related to the needs of the local community and the level of their satisfaction. These issues include, among others, access to public services, health protection, culture and recreation, education, public safety, transport and communication as well as social security, tourism and recreation, natural environment.

Table 1 presents the residents’ assessment of the degree of satisfaction with the possibilities to meet the needs in selected areas determining the quality of life. In this comparison, the city’s residents’ access to grocery stores and the Internet stood out the most. A significant proportion of respondents indicated a rather high degree of satisfaction with education, social assistance, public security and access to services. This was a positive phenomenon due to the sufficient level of public security in the respondents’ opinions, which is one of the most important components of local sustainable development. The lowest level of satisfaction rated by respondents in 2017 and two years later was with their needs in the fields of health protection, professional development and public transport.

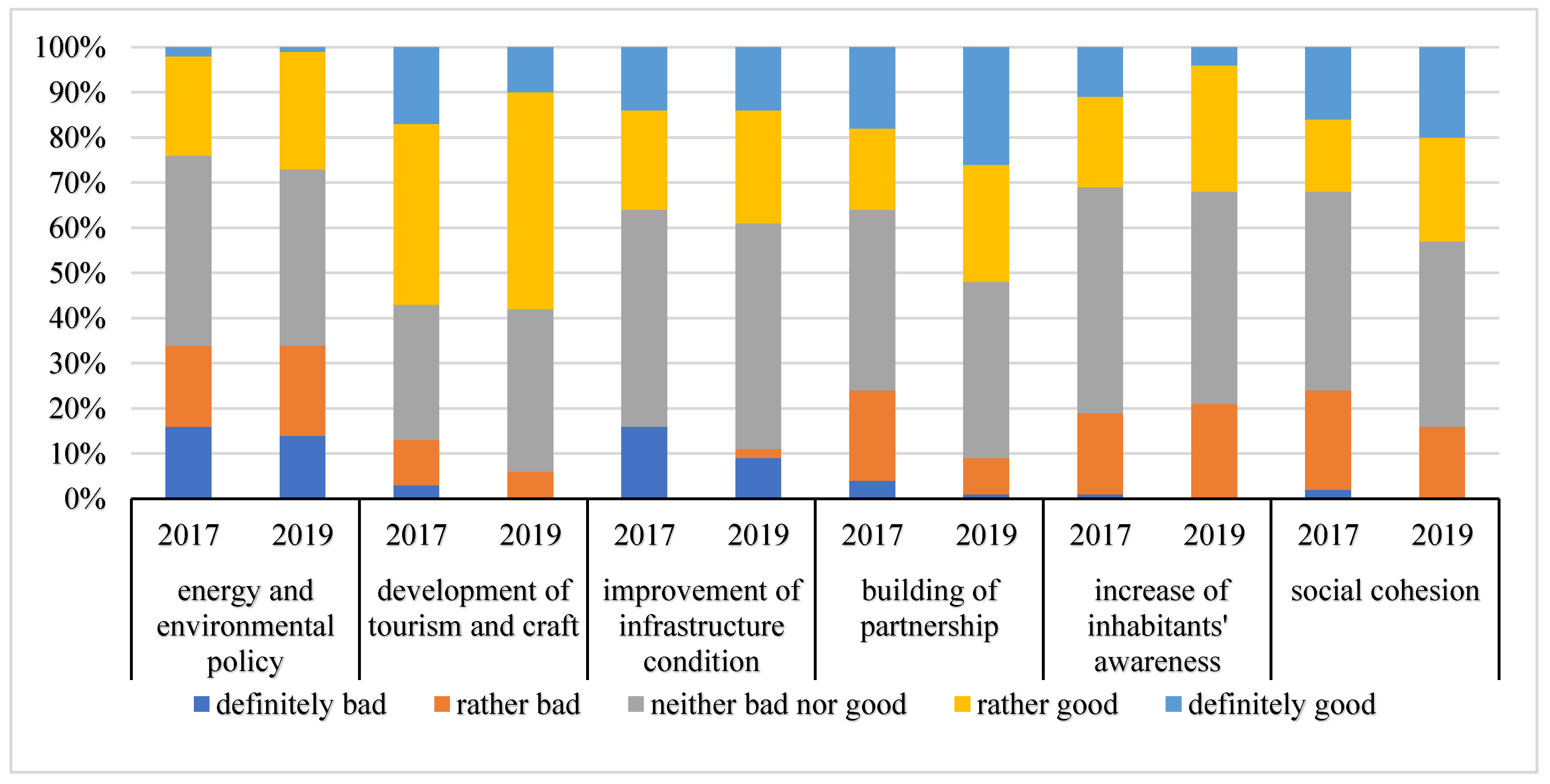

Figure 2 presents changes in assessments of actions taken by the city authorities in individual categories. As it can be observed in the opinions of respondents, during the two-year interval all groups of activities undertaken by the city authorities were assessed better, especially those related to building of partnership and social cohesion. Activities aimed at development of tourism and craft were rated highly by more than 50% of participants in both surveys (

Figure 2).

The research showed that there was a clear progression in regards to inhabitants’ evaluation of the undertaken activities in the areas that are the domain of the Cittaslow idea. As noted by Gruszecka-Tieśluk [

8], strong local communities cannot be built without bottom-up initiatives, and these will not appear until people see the effects and benefits of their city’s membership in the association. Therefore a favorable prognosis appeared where a significant improvement in respondents’ assessments of the sphere of building of partnership was observed. In 2017, the activities of the authorities in this area were assessed as definitely beneficial and advantageous by 38% of respondents; in 2019 it was 52% of research participants (

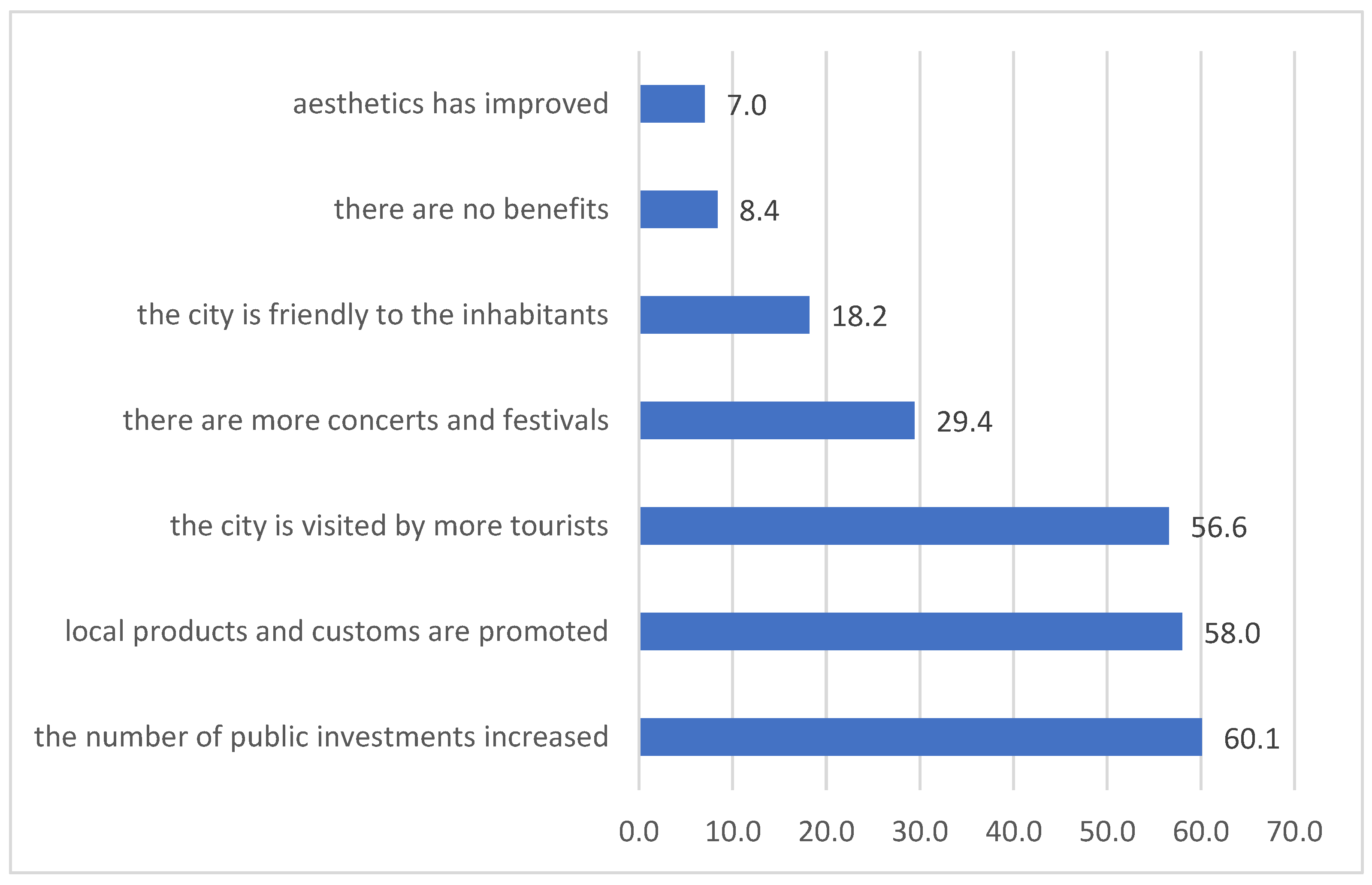

Figure 2). In the next question, the respondents referred to the benefits of being a member of the network. The question was in an open form and the obtained results were averaged. Answers were received from a total of 146 people, including 76 participating in the 2017 research and from 70 responding in 2019. Among the examples of the responses there was a statement included that participation in the network did not bring any benefits. This response was given by 8.4% of respondents. The most popular answer was the statement that the number of public investments increased. Promotion of local products and customs has improved and respondents observed an increase in the number of tourists visiting the city (

Figure 3). The city is visited not only by tourists from Poland, but also from abroad. They are mainly vacationers from Germany.

The benefits perceived by the inhabitants, in addition to being associated with the city’s membership in the Cittaslow movement, were an important source of change for the development of the local community.

A significant role, especially in the beginnings of the Polish National Cittaslow Network, was played by the Marshal’s Office of Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodship, which initiated many activities for the promotion and integration of Cittaslow towns. The involvement of the so-called “supporting members” and “friends of Cittaslow” as well as the support of the scientific committee of the Cittaslow network may prove crucial in the next stages of development of the national network after the implementation phase.

One of the most important initiatives is the Supralocal Revitalisation Programme for the Cittaslow Network. This program is a strategic document with operational elements based on the diagnosis of existing problems in the physical, economic and social space. The objective of the supralocal revitalization program for the Cittaslow network towns is the parallel, coordinated and targeted revitalization of the towns in the Warmia and Masuria region so that, while preserving their unique character and values, they can at the same time offer their inhabitants a similar quality of life. The implementation of the Supralocal Revitalisation Programme of the Cittaslow Network of towns is to contribute to the improvement of the region’s image (it will be perceived by the local community and visitors as a place where one lives in harmony with the surrounding environment; a friendly place where it is worth living, raising a family and investing). Such activities are also in line with the Strategy of Socio-Economic Development of Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodeship until 2025, where the vision of the region was defined as a place where it is worth living irrespective of age, education and property status. The projects implemented are in line with the objectives of the strategy [

46]:

- -

well-developed technical, tourist and social infrastructure,

- -

development and use of tourist potential,

- -

development of entrepreneurship,

- -

educated, active, involved society and internal integration of the municipality.

In the framework of the revitalization of the degraded area of the Old Town, in order to restore its function as the economic, social and cultural center of Lidzbark Warmiński, a number of actions are planned. The most important ones include:

- -

reconstruction of the old railway station with preparation of rooms for the needs of social economy entities,

- -

restoration of the defensive walls,

- -

renovation of devastated tenement houses (vacant buildings owned by the Municipality) with new functions,

- -

development of public space for recreational purposes covering built-up areas and the dry moat as well as the valley of the Łyna River, construction of traffic routes, elements of small architecture, lighting, fountains, planting high and low plants, green areas,

- -

illumination of the Old Town facilities,

- -

implementation of monitoring,

- -

carrying out audits and technical documentation of thermal modernization of buildings, insulation of community buildings, replacement of windows, external doors, modernization of the heating system with a connection to the heat source,

- -

renovation of the historic organs in the Church of Sts. Peter and Paul,

- -

modernization of the amphitheater through rebuilding the auditorium, construction of technical facilities, stage and roofing,

- -

purchase of regional costumes and musical instruments,

- -

promotion of cultural events with a regional character,

- -

tourist signposting.

A specific way of integrating the inhabitants around the idea of Cittaslow is the organization of meetings, events and open-air events under the logo of the movement, during which local producers are promoted, especially those dealing with food production. The towns cooperate with one another, organizing joint festivals and promotional activities. The most popular event organized by Cittaslow is the Town Festival. It takes place regularly in various cities around the world, including Lidzbark Warmiński as a host in 2011. Another initiative appreciated by the inhabitants of Lidzbark Warmiński was the project “Lidzbark Warmiński—Two Faces—from the Past to the Present in Word and Image”. The aim of the project was to bring the inhabitants closer to the history of the town and to involve them in its implementation. The cities belonging to the network are distinguished by: location attractiveness, landscape and natural values of the surrounding area, interesting cultural heritage, local culinary offer based on natural products, support of economic initiatives in the field of local crafts and handicrafts, high quality of products and services offered. Developing the tradition of hospitality also makes them attractive to tourists.

The quality of life of the inhabitants is inextricably linked to having a source of livelihood. Therefore, all investment projects were linked with activities in the social economy sector and self-employment. It was assumed that as a result of project implementation degraded historic buildings will be restored and revalorized, and given new functions. New, aesthetic public spaces will be created, the valley of the Łyna River will be developed for recreational purposes, the amphitheater will be modernized, which will improve the attractiveness of the revitalized area. Social economy entities will develop whose task will be to activate people socially excluded or at risk of such exclusion, which will improve the quality of life [

46].

It should be noted, however, that strong local communities cannot be built without grassroots initiatives, and these will not appear until people see the effects and benefits of their city’s membership in the association. As it was observed, the first effects are already visible, because the movement is developing and new towns are joining, especially from the region of Warmińsko-Mazurskie voivodeship.

4. Discussion

As emphasized by Farelnik et al. [

15], the scale and scope of positive changes occurring in Cittaslow towns depend on many factors, such as the degree of involvement of local authorities in the implementation of activities in line with the Slow City concept, the ability to cooperate with other cities in the network, the awareness and knowledge of Cittaslow’s principles among the towns’ inhabitants, the degree of participation and involvement of local entities in promoting the idea of development of their towns in the spirit of Cittaslow. The availability of resources (own and external) in the member cities and the recognition of the Cittaslow brand are also important, as well as the development of network links, the experience gained during the implementation of various projects in cooperation, in particular, the creation of network products of cities [

15,

20,

47]. It is worth emphasizing that the changes taking place in Cittaslow cities also depend on exogenous conditions, both national and international.

After several years of program implementation, it can be seen that the Cittaslow concept is conducive to protecting tradition and local culture. The Cittaslow movement promotes care for the environment and preservation of local customs, and as one can see, the local community is not yet aware of this area. The authorities of Lidzbark Warmiński put special emphasis on respecting the local tradition, cultural values and broadly understood care for the natural environment (promoting alternative sources of energy, recycling, limiting exhaust fumes—excluding car traffic from the old town, creating green areas, places for rest and recreation and others). Cittaslow gives member towns the opportunity to be part of a network on both a local and international level, as pointed out by many authors [

27,

42,

48,

49]. Erdogan [

10] rightly noted among his respondents that Cittaslow is a kind of philosophy of life, which, moreover, is perceived very positively by residents. Cittaslow’s philosophy is to seek a healthy balance between economic growth, social development and the protection of local traditions and cultural identity [

14,

26,

50,

51,

52,

53]. This positive picture was reflected in the results of the conducted surveys, in which the participants were increasingly positive about both the degree to which residents’ needs are being met and the activities undertaken by the city authorities.

One of the goals of the city’s functioning in this network is to promote and implement solutions that improve the living conditions of both current and future generations. Opinions obtained from respondents indicated, among others, that the socioeconomic situation of the inhabitants is gradually improving.

The Cittaslow idea is supported by the concept of sustainable development [

11,

17,

27,

32]. Thanks to it, three areas of activity are connected: environment, society and economy [

42]. Each of these areas is equally important. In order for the socioeconomic development process to proceed correctly, each element must be in balance. Radical changes result in a decrease in efficiency and disrupt the process of sustainable development. In the framework of promoting the idea of Cittaslow and the city as a member of the network the awareness of the local community about the activities undertaken to improve the quality of life is a phenomenon beneficial for the development, provided that the activities of the local authorities belonging to the network are not limited to using the idea as another initiative without an implementation plan and proper financial resources. Small towns like Lidzbark Warmiński can benefit from joining networks at the local level [

54], especially regarding their socioeconomic development.

The implementation of the Cittaslow idea is strongly influenced by the institutional efficiency of the municipalities, which largely depends on the municipality’s own income and spatial policy [

55] and on basic areas of activity (economic and spatial, financial, administrative, human resources management in municipal offices, provision of social, cultural and educational services) [

56,

57]. The results of Maleszyk and Kędra’s [

58] studies confirmed that local measures aimed at reducing depopulation, which focus exclusively on improving housing conditions and the quality of the neighborhood, can only be partially effective in retaining residents in the city. Sustainable urban development, including membership of cities in the Cittaslow, is a guarantee of a better life satisfaction. Thus it can also attract new residents.

On the basis of surveys conducted among the inhabitants of Lidzbark Warmiński, opinions on the impact of the city’s membership in the International Cittaslow City Network were obtained. Research showed that Lidzbark Warmiński’s participation in the International Network of Cities of the Good Life is conducive to creating a sustainable development model. The undertaken initiatives, in line with the idea of “slow”, were accepted and positively evaluated by its inhabitants, which was confirmed by the results of the obtained surveys. In 2017, Batyk and Woźniak [

59] conducted research in 10 Polish cities belonging to Cittaslow, including, among others, Lidzbark Warmiński, and they also confirmed inhabitants’ satisfaction with belonging to the network. However, inhabitants of as many as seven cities had a different opinion. The cooperation of cities belonging to the Cittaslow network in Poland concerns mainly the development of tourism and urban promotion [

60]. Tourist attraction is increasing, owing to which Lidzbark Warmiński has become a popular place of arrivals for groups and people from other regions of Poland and other countries. This translates into a perceived role in the promotion of local tourism. This is also highlighted in their research by Zadęcka [

31] and Gruszecka-Tieśluk [

8] in the case of Lidzbark Warmiński. Similar observations about the importance of the Cittaslow movement were made by İlhan et al. [

24] on the example of the Turkish city of Tarakli. Since this city became a Cittaslow member, the number of tourists has increased, which ultimately helped combat unemployment and also increased the income of the residents. The importance of tourism in the Cittaslow movement was also confirmed by many scientists in their research, including: [

9,

12,

20,

27,

61,

62]. A new phenomenon is also the idea of Slow Sport, which also fits in with the balanced development of cities as required by Cittaslow [

63].

The vast majority of research participants—the inhabitants of Lidzbark Warmiński—believed that their quality of life has improved. New investments have contributed to improving the quality of life in the city. For this reason, the inhabitants of Lidzbark Warmiński positively perceived the idea of Cittaslow. Only a small percentage of residents believed that the city’s membership in the network negatively affected the city’s development. As emphasized by Wierzbicka [

42], the model of Slow City development should be individually adapted to the capabilities of each city or group of cities similar in terms of the level of socioeconomic potential. This is particularly important in the case of small cities (such as Lidzbark Warmiński) [

64]. The implementation of the Slow City model guarantees numerous benefits for small cities in the economic, social, spatial, environmental, organizational and image spheres [

65]. These benefits in turn contribute to the real development of cities [

66] (p. 104).

The town of Lidzbark Warmiński, owing to its membership in Cittaslow network, has repeatedly been the subject of research [

43,

58]. Strzelecka [

43] stressed that Lidzbark Warmiński is an example of a city that has changed its quality of life. Also interesting were the conclusions of the research undertaken by Rutkowska [

67], which was the first to address the issues of Lidzbark Warmiński’s membership in the Cittaslow cities network, including focusing on the quality of life in the city in various aspects of this concept. Among a large group of respondents (over 500 people) about 40% supported membership in the network and only 6% were against participation in the movement. In her conclusions, the author Rutkowska [

67] indicated the need for continuing research. This article is an example of such research. It is worth noting that the conviction to belong to the Cittaslow network is increasing among the residents. The inhabitants are satisfied, but also more aware. They are looking for their own, sustainable dimension of quality of life.

5. Conclusions

The city operates in accordance with the principles of sustainable development, cares for natural resources and does not carry out activities that could excessively degrade them. Hypothetically, it should be noted that being outside of the movement, the city of Lidzbark Warmiński could undertake actions to improve the quality of life of the residents, as this is the basic role of the local authorities. Nevertheless, by integrating the city development strategy with Cittaslow principles, city investments are changing the space to become visually more attractive for both the inhabitants and visitors.

Implementing the development strategy of Lidzbark Warmiński in the spirit of Slow allows the local authorities to focus their attention on such important issues as environmental protection and promotion of ecological attitudes, taking care of the historic city tissue, promoting the so-called culture of hospitality, promoting local goods and products, eliminating architectural barriers, improving the work of local administration. This undoubtedly adds a whole new practical dimension to the activities of local authorities. The quality of life of residents has improved. The city is developing. New investments change the city space, which makes it visually more attractive for both residents and visitors. Owing to new investments, more and more tourists from Poland and other countries are coming to Lidzbark Warmiński. This is associated with increased traffic in the city, resulting in local entrepreneurs gaining new customers. The gastronomic and hotel base has developed significantly during this time. Entrepreneurs have adapted their offer to the requirements of the dynamically developing market of tourist services.

However, despite these clearly outlined trends, it remains open to clarify to what extent these positive changes are due to the implementation of the program in question, and to what extent they are a consequence of other factors. This situation indicates that there is a lack of precise tools to analyze the impact of the program. As confirmed by Strzelecka [

68], in the case of small and medium cities, networks enable taking advantage of economies of scale, which further improves their competitiveness. For these reasons, when observing the dynamic development of the Cittaslow idea in local environments—small cities—it is important to thoroughly analyze and observe the phenomenon. The research allowed to learn the opinions of the community regarding the level and quality of life in Lidzbark Warmiński and the activities of local authorities for the development of the city. Residents also assessed the degree of satisfaction of their needs and the level of development of the city. Obtaining the opinion of residents regarding the Cittaslow network as a direction of local development, as well as assessing its impact on the quality of life of the urban community, turned out to be important from the perspective of further analysis.