Abstract

The need to incorporate the gender dimension in higher education is a central element of gender equality policies within the European Union (EU). When most institutions of higher education have already strengthened and consolidated their curricula, the next challenge is to include and ensure that all people have the same opportunities to progress in education. This study intends to incorporate the gender dimension in teaching through a guide providing recommendations for the introduction of changes that will allow its effective incorporation in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) areas. It will take into account the administration in charge of formulating policies in the field of education, the students, and, mainly, the teaching staff. Its objective is to cover aspects related to the principles of equal opportunities and gender equality in STEM higher education disciplines. For this purpose, 41 volunteer teachers from 8 degrees and master’s degrees from the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya in Spain participated. To achieve the results of this study, aspects related to social and gender relevance of the subjects, inclusive methodology, classroom management and assessment were considered. As a preliminary step to the development of the guide of recommendations, a teacher’s self-assessment tool and a questionnaire for students to analyze the perception of the gender dimension were developed.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The lack of engineers is a challenge for society in the future. According to experts [1], by 2025, 7 million jobs will have to be filled in Europe in the STEM areas (for the acronyms Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics). There is currently a shortage of women in these sectors and especially in the Information and Communications Technology (ICT) sector, so it is necessary to offer the female group the opportunities for a social lift related to a professional future in these fields [2,3]. In addition, this lack also means a loss of talent and diversity for society as a whole (women make up more than 50% of the population).

Gender equality affects the performance of teaching and research and should facilitate that teachers and students understand the underlying gender norms in society, as well as their intersection with other axes of inequality (ethnicity, social class, sexual orientation or functional diversity). It is necessary to train future generations of teachers and researchers by including the gender dimension in these disciplines [4] and pay special attention to all relevant related aspects that must be treated from a gender dimension throughout the entire cycle of training and research. Introducing the gender dimension allows us to deepen our understanding of the needs, behaviors and attitudes of the population as a whole, thus avoiding both partial interpretations that start from the man as a universal subject, and essentialisms about men and women. Including the gender dimension in teaching improves the teaching quality and the social relevance of the knowledge, technologies and Innovations produced.

Numerous studies [5,6,7] indicate that people’s behavior is determined by implicit or unintended biases derived from the repeated exposure of generalized cultural stereotypes. Over the years it has been found that the production of knowledge and the vision of science itself has been linked to men; it is called blindness towards the gender dimension (gender blindness). It is defined as the fact of not taking into account the roles and responsibilities assigned to individuals according to gender norms when developing projects, public policies or programs of all kinds. This lack of attention to gender issues contributes to maintaining the status quo, inequalities and the biases that come from it. Scientific research, from biomedical sciences to engineering or social sciences, has been surprisingly blind, not only towards gender aspects, but even towards aspects as basic as differences between people. Furthermore, critical thinking avoids gender blindness (stereotypes and social roles) in future professional practice.

If science has been built from an androcentric vision, and originally with little participation of women, it is not surprising that the knowledge transmitted to students is gender biased. It is also not surprising that the generic student profile does not include diversity aspects or that some pedagogical or evaluation practices are also affected by gender biases, by not taking into account potential differences in the ways of learning, working and communicating due to social stereotypes.

Several studies have considered the potential impact of gender on the implementation and sustainability of the engineering-design-based instructional approach as a best practice to enhance STEM teaching. Women, irrespective of their desired science career, were more likely to be interested in addressing issues pertaining to disease, poverty and distribution of wealth and resources, and food availability [8,9].

Understanding gender differences in motivation to perform outreach could lead to enhanced engagement of both men and women in outreach and service-learning activities. Some studies have investigated the potential of a service-learning experience to support STEM engagement for underrepresented youth. It has been shown that the use of service-learning in the science and math curriculum would help promote the entry of women and minorities into STEM fields, increase the potential pool of engineers and scientists, contribute to the development of STEM educators and enhance cultural sensitivity, ethics and social responsibility in future STEM workers [10,11]. Although women have nearly attained equality with men in several formerly male-dominated fields, one important reason for this discrepancy is that STEM careers are perceived as less likely than careers in other fields to fulfill communal goals (e.g., working with or helping other people) [12,13].

Research shows that gender differences in interest and self-concept (typically assessed with self-report measures) significantly affect the choice to pursue STEM-related studies and careers, as well as performance in STEM [14]. The low number of women that persist in STEM disciplines is a current problem that has manifested particularly in the engineering collegiate environment [15]; women aptly competent in mathematics often fail to pursue mathematics-related careers because they have low self-efficacy perceptions about their competence.

Several studies highlight living and learning communities as a factor contributing to student persistence, particularly in STEM programs. Findings indicate that providing women with the opportunity to live together within one residence hall and take classes together has three main effects. It creates a strong sense of community, provides confidence-boosting professional development, and ultimately helps students stay in engineering [16].

Lack of diversity, and specifically, gender diversity, is one of the key problems that both technological companies and academia are facing these days, as pointed out by Botella et al. (2019) [17]. An important factor to reverse this problem is increasing the visibility of female role models [17].

The need to incorporate the gender dimension in higher education is a central issue in gender equality policies within the European Union (EU). These are part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in the 2030 Agenda [18], specifically in the education goals of quality, gender equality and reduction of inequalities [19]. It is necessary for educational institutions to implement initiatives to create awareness about the gender gap, promoting a gender-sensitive culture since even the disciplines traditionally considered as oriented to women may experience a leak and that female students move to other areas. The application of these programs would help to increase the proportion of female students in those areas, such as STEM disciplines, in which they traditionally show a lower proportion [20]. In addition, the incorporation of the gender dimension in teaching should provide an equitable look to understand inequalities due to sex-gender and sexuality and to bear in mind their implications throughout the learning process [21,22,23]. Reports published by governments and academic institutions around the world show similar data in relation to these inequalities, showing that it is a global problem. Although several countries have achieved gender balance in university studies, women only represent between 20 and 30% of the student body in engineering studies [24].

From the EU, Spain has been called upon to fulfil its international commitments on education and gender equality with recommendations such as ensuring the elimination of gender stereotypes from textbooks, the inclusion of women’s rights in curricula, the promotion of gender equality in teacher professional training and the demand that gender training be not relegated to the background.

Following the recommendations of the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) (http://www.unwomen.org/en/csw, accessed on 1 April 2021), the Agència per a la Qualitat del Sistema Universitari de Catalunya (AQU, http://www.aqu.cat/, accessed on 1 April 2021) has prepared a document that establishes guidelines and recommendations to facilitate the effective incorporation of gender dimension in teaching in all areas of knowledge [25]. It is a first step towards the fulfillment of the mandate of article 28 of Law 17/2015, of 21st July [26], of effective equality of women and men.

Many researchers have developed tools in order to promote an inclusive management of teaching, but the scientific literature shows a lack of higher education teaching guides in STEM. While most recommendation guides are not about engineering, the challenge is to create and adapt them to the specific needs and contexts of these areas [27,28,29,30,31,32]. These tools should emphasize the need to integrate a greater variety of experiences, providing opportunities to express themselves through the choice of topics, references or own examples. The guide prepared in this study is inspired in existing guides on the introduction of the gender dimension in teaching, such as the guides prepared by the Xarxa Vives d’universitats.

The Xarxa Vives d’universitats (https://www.vives.org/, accessed on 1 April 2021) has so far produced 17 guides on different disciplines and areas of knowledge for higher education with a gender dimension [33]. The aim of the collection is, on the one hand, to offer resources to university teaching staff to help them pay attention to gender dynamics in the learning environment and to adopt measures that guarantee attention to the diversity of students. On the other hand, students can use them to identify gender stereotypes, norms and social roles, develop their critical spirit and acquire skills that allow them to avoid gender blindness in their future professional practice. One of these guides, the one corresponding to Industrial Engineering [34], was inspired in the recommendations’ guide developed in this research.

Other useful resources come from the Effective Gender Equality in Research and in Academia (EGERA) project [35], which compiles some good practices in various teaching fields and suggests strategies to achieve such integration beyond the integration of the gender dimension in subjects where it is relevant. It is possible to develop thematic undergraduate/graduate/doctoral subjects on gender issues.

1.2. Research Environment

The Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (UPC) (www.upc.edu, (accessed on 1 April 2021)) is a public university specialized in the fields of engineering, architecture, science and technology. In 2020 it was ranked as one of the best polytechnic universities in Spain and at number 76 in the world ranking of engineering and technology universities according to QS World University, as well as the first European university in Erasmus Mundus masters. During the 2020/2021 academic year, 28,208 Bachelor and Master degree students were enrolled, of which 28.6% are women and 71.4% are men.

University Bachelor and Master degree studies with fewer female students enrolled at UPC include Computer Science (14%), Telecommunication Engineering (19%), Naval, Marine and Nautical Engineering (16%), Engineering (Mechanical, Electrical, etc.) (20%) and Aerospace Engineering (24%). In contrast, in health science and technology degrees, 72% of students enrolled are women; in Biosystems Engineering, they are 44%, and in Architecture, Urban planning and Building degrees, they are 46% of the total number of students enrolled. These indices are also valid at the international level [36].

The interest in the introduction of the gender dimension into regulated studies at the UPC is not surprising, as this university has been involved in gender projects since many years ago (for example, the project TECNOIA at the end of the 1990s, or the Woman Program in 1997). Currently, through the implementation of the III Gender Equality Plan 2016–2020, this university promotes actions aimed at ensuring nondiscrimination, as well as fostering gender policies in decision making, academic career and gender dimension in teaching and research, such as T’steam [37], +GirlsTIC, M2m, Time Reform and Glass Ceiling, among others. In addition, the UPC is a partner of a European project H2020 (2017–2021) Gender Equality in Engineering through Communication and Commitment, (GEECCO), which encourages the development of gender equality plans in research performing organizations (such as universities) and the incorporation of the gender dimension in teaching as its main axes. Recently, in April 2020, the UPC approved the new gender competence that the curricula will have to include. According to this, all the Bachelor and Master degrees taught at the UPC will have to progressively incorporate the new “Gender Dimension” competence, for its implementation from the 2021/2022 academic year.

In this favorable environment of experiences in promoting gender and non-discrimination policies at the authors’ university, it is especially important that the knowledge produced by research and transferred through teaching be free from gender bias. For this reason, the UPC developed in the 2018/2019 academic year a pilot project named Gender Dimension in Teaching (its acronym hereafter will be GDT), where a cooperative approach was adopted to reach gender mainstreaming in all Bachelor and Master degrees at UPC.

1.3. Objectives and Research Questions

The objectives of the GDT project were:

- −

- Main objective:

To develop a guide of recommendations to be used by all the teaching staff at the UPC to introduce the changes that make possible the effective incorporation of the gender dimension in teaching in STEM fields.

- −

- Secondary objectives:

- To build capacity of participating academic staff of GDT project, giving them the appropriate tools, so that they could redefine their courses incorporating the gender dimension in teaching;

- To create a survey template to assess the perception and situation regarding the gender dimension in teaching in both teachers and students;

- To help integrating this much-needed dimension in all the curricula of the UPC, in the medium–long term in order to comply with the requirements of the AQU, which enforces the incorporation of the gender dimension in all the Bachelor and Master degrees in Catalonia by 2021.

In addition, the following research questions were posed:

- Is it possible to reach a consensus within the teaching staff on what would be the best way to incorporate the gender dimension in teaching?

- What were the strengths and weaknesses of the project participants regarding the application (in their subjects) of the gender dimension before the start of this experience? And at the end of the project?

- What are the priority actions when implementing the gender dimension in teaching?

- What was the perception of the students in the application of the gender dimension in the participating subjects?

1.4. Theoretical Framework

The work presented here is driven by the appearance of a new general framework and of prompt application to the entire Spanish educational landscape and aims to cover aspects related to the principles of equal opportunities and gender equality. It will take into account the administration in charge of formulating policies in the field of education, the student body and mainly the people who pursue university teaching. Tools will be provided to teaching and research staff to be able to incorporate all these skills. These tools include training courses, multidisciplinary work teams and a guide with recommendations. The guide could also assist the educational policy review process.

According to the AQU framework document [25], four fundamental pillars (curriculum development) were considered in this research: 1. Course contents, 2. Teaching methodology, 3. Classroom management and 4. Assessment processes. Each pillar was reviewed with respect to the gender dimension and gender issues were identified according to the experienced perception by the participants in this study. Table 1 shows the description of the different aspects that were addressed and on which it was intended to emphasize.

Table 1.

Description of the pillars (curriculum development) on which the GDT project is-based.

Common stereotypes associate high-level intellectual ability (brilliance, genius, etc.) with men more than women. These stereotypes discourage women’s pursuit of many prestigious careers; that is, women are underrepresented in fields whose members cherish brilliance (such as STEM fields), as [38] illustrates.

One of the most common actions from a gender dimension in teaching regarding course contents and, at the same time, a more immediate implementation is the introduction of female references in the field. This scenario concerning the referents of our students can strongly condition the professional expectations of our students and it is urgent to take measures in this regard [17].

Learning is not just determined by the curriculum, but by how it is assessed. Some studies highlight that assessment practices in higher education can be enhanced through improvements in the design of assessment. Feedback, participation, empowerment and self-regulation are identified as mediating effects of the quality of assessment tasks on learning [39].

Regarding assessment, there are several studies which analyze different experiences on evaluation from the point of view of the gender dimension, as [40,41,42,43]. For example, in [44,45] it is shown that in multiple choice tests where wrong answers are penalized with negative points women performed worse, mainly due to a lower self esteem.

There is evidence that women tend to perform worse in many competitive settings than men, which affects not only the assessment processes but also the teaching methodology and the classroom management (classroom participation, individual or group work, etc.). Inclusive teaching strategies and classroom characteristics have proven to improve students’ social participation [46,47].

Each one of the pillars shown in Table 1 was divided into a second level of performance. This level was suggested by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) study [48] on the results by gender in the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) tests and the results on the lack of interest of Spanish women towards ICT studies [49]. In this second level of action, three aspects were asked: 1. Interdisciplinarity, 2. Self-concept and 3. Capacities. Table A1 (Appendix A) shows a list of the main issues according to the previous classification.

2. Methodology

The Gender Dimension in Teaching (GDT) pilot project has been the platform from which evidence has been collected to answer research questions.

GDT project has been carried out using a methodology based on cooperative work through face-to-face sessions. Within the framework of this project, the participants designed and implemented gender dimension activities in their subjects and special attention was paid to the development of indicators that would allow the evaluation of the project after its completion.

The selection of the work teams participating in this project was carried out by a leading team appointed by the UPC. In November 2018, a call was made to select the teams that participated in the project. This call was open to all the faculty from the authors’ university. Each work team had to be composed by a minimum of three teachers from the same degree and at least three subjects per team were covered. This requirement pursued the objective of ensuring a future dissemination of knowledge within the degree, in order to maintain a certain degree of sustainability in the action. This project would also be applicable to Bachelor and Master theses. In addition, the groups were required to respect, as far as possible, the criteria of parity, to have previous experience in gender or teaching innovation and to have the institutional support to ensure a certain echo of the action within the executive councils, in order to facilitate the continuity of the action.

A total of eight work teams responded to the call. These teams covered a wide range of STEM studies (including Architecture, Civil Engineering, ICT Systems Engineering, Naval Systems and Technology Engineering, Aerospace Systems Engineering, Applied Telecommunications and Engineering Management, Industrial Engineering and Environmental Pathways for Sustainable Energy Systems). The total number of teachers participating in the project was 41 (59% women). The majority age range of the participants was 35 to 45 years (48%) followed by the 46 to 55 age range (32%). Seventy-seven percent of the teaching staff had more than 11 years of experience and 78% were course coordinators (of which 53% were women).

The detailed information (school or faculty, Bachelor or Master degree, covered courses, involved teachers and involved students) on the work teams participating in the project is shown in Table A2 (Appendix A). Within the team of participants, there was the presence of two gender equality school/faculty responsibles (a man and a woman) from two different faculties, a female member of the Equality Unit of the UPC, two female members of the Institute of Education Sciences and four female members of the GEECCO project. In addition, the team included people with extensive experience in teaching innovation. Therefore, it can be said that the project team was made up of people who were very involved in improving teaching and very sensitive from a gender dimension, although in areas other than teaching.

The meetings with the teachers were structured around five face-to-face sessions (Figure 1). The sessions were from January to June 2019, coinciding with the teaching of the second semester of the 2018/2019 academic year. The opening session (Session 1) was a five-hour session, and the remaining sessions were three hours in length.

Figure 1.

Timetable line of the GDT project.

With the exception of the kick-off meeting (Session 1), each face-to-face session focused on one or two of the key pillars of teaching (course contents, teaching methodology, classroom management and assessment processes). In each session, the leading team promoted the discussion, either from bibliographic information or from data obtained throughout the project (see Results section). In this discussion, an attempt was made to reach a certain consensus on what would be the best way to incorporate the gender dimension in the field of the pillar studied in the session. At all times, participating GDT members were urged to apply the proposed and often-agreed measures to teaching in the spring semester (February–June 2019).

The pillars of classroom management and teaching methodology were discussed in the second session in the form of an open discussion about one’s own experiences. The course contents pillar was addressed in the third session based on a group dynamic where attendees were divided into groups of 3–4 teachers, forcing interdisciplinarity. The activity began with the description of one of the subjects taught by a member of the group. The rest listened and then posed questions to try to relate the contents of the subject with society, seek the real utility of the subject and the target. After about 10–15 min, the teacher and subject were changed. The aim was for the teacher to be able to acquire a more global view of his/her subject by explaining it to someone completely external, so that he/she could detach himself/herself from the concretion and focus more on the utility and the real beneficiaries. Based on questions from the rest of the team, perhaps a new perspective could be reached on the topic and its usefulness or potential.

The assessment processes’ pillar was discussed in the fourth session. The state of the art in this field was initially shown, analyzing different experiences of evaluation from the point of view of the gender dimension [43]. Formative and summative evaluation were described [50,51], both important for the development of learning. The relevance of feedback as a motivating element for formative evaluation was also mentioned. As assessment instruments, rubrics, checklist and scales were taken into account [52], all of which were implemented using an egalitarian and equitable approach [53]. Next, the experience in this field in teaching at the UPC was discussed.

In the fifth and last session, some of the results of the introduction of the gender dimension in several of the participating subjects were presented, and the whole GDT project was assessed.

The description of each one of the sessions of the project can be seen in Table A3 (Appendix A).

Several indicators were defined, both qualitative and quantitative, to measure the degree to which the objectives of the research were achieved.

Qualitative indicators are the set of impressions, reactions and proposals of the participating members obtained throughout the project. The types of modifications incorporated by GDT members in their teaching during the spring semester are also considered qualitative indicators, as well as the qualitative assessment and reflection that were made at the end of GDT project. Evidence of these modifications is provided by the fact sheets requested throughout the project and the results of the application of the pre-test/post-test methodology. This methodology consists of collecting tests at the beginning of the course on the perception and knowledge of teachers and students about some aspects of gender that you want to work on during the course. Once the corresponding actions had been carried out throughout the course, their effectiveness was assessed by gathering new evidence and comparing it with that collected at the beginning of the course. This methodology had already been applied previously in [54,55,56]. A simple example would be to ask students in the pre-test to cite the full names of five female referents and five male referents in the field of study; during the course, the teacher would present referents, especially of the gender that has detected a deficiency; at the end of the course, in the post-test, the same question would be asked to the student again and compared with the results of the previous test.

To apply the pre-test/post-test methodology, different tools were designed and implemented: for the pre-test stage, a teacher’s self-assessment questionnaire and a student’s perception questionnaire; for the post-test stage, a final assessment questionnaire. The three tools are described below.

2.1. Indicator 1: Teacher’s Self-Assessment Questionnaire

The teacher’s self-assessment questionnaire was designed before the face-to-face sessions with the aim of assessing the degree of introduction of the gender dimension in the participants’ teaching. In fact, this is the pre-test of the study and was very useful to start the debate held throughout the GDT project.

Moreover, this questionnaire can be understood as a starting point for the guide, including some actions to be discussed, modified and extended during the GDT project. The introductory questions to the survey focused on aspects related to gender, age, professional experience, job category, subject coordination, etc.

The survey questions were distributed among the four pillars on which the GDT project is based (Contents, Methodology, Classroom Management and Assessment) [40].

2.2. Indicator 2: Student’s Perception Questionnaire

The student’s perception questionnaire responds to a need that arose throughout GDT to have an indicator to know to what extent our prejudices and interpretations regarding the students corresponded to reality. The issues raised are, in fact, a result of the GDT project and are discussed in depth in Section 3.2.

2.3. Indicator 3: Final Assessment Questionnaire

The final assessment questionnaire has a triple functionality: (1) it is the post-test of GDT and allowed us to know its effectiveness, (2) it answers the questions of the research, as it is an indicator of the degree of consensus among GDT members in terms of prioritizing actions to introduce gender dimension in research, and (3) it provides the elements for the elaboration of the UPC guide.

The final assessment questionnaire includes the following sections: (I) identification, (II) assessment of the sessions, duration, content and methodologies, (III) the prioritization of each action with a gender dimension that could potentially be included in the guide and (IV) assessment of the degree of introduction of the gender dimension in the teaching before and after the GDT project.

The questionnaire is not anonymous (Section (I)), as it is very useful to be able to relate the different answers depending on the person. In fact, aspects such as previous experience, attendance and attitude during the sessions and the application of some actions to one’s own teaching during the GDT project are useful aspects to be able to interpret the results correctly.

The post-test itself consists of sections (II) and (IV).

Section (II) is the indicator of the degree of consensus among GDT members regarding the prioritization of actions to introduce the gender dimension in research, i.e., it directly answers research questions. In addition, it provides guidelines for the development of the UPC guide. Section (III) is of the multiple selection type, where GDT members had to classify different actions. The actions analyzed are the result of the adaptation of the list of actions defined at the beginning of the GDT project based on all the comments made by the participants in the framework of the project.

This link shows the final assessment questionnaire of the GDT project:

https://tinyurl.com/y4umzyol, accessed on 1 April 2021—Catalan language.

3. Results and Discussion

Without intending to summarize all the activities carried out throughout the GDT project and the corresponding results obtained, below there are only the results of the key actions to obtain evidence to reach some conclusion on the research questions.

3.1. Teacher’s Self-Assessment Questionnaire

This questionnaire was distributed among the participating teachers through a Google Forms form (http://tiny.cc/awkmsz-Catalan language, accessed on 1 April 2021). Each teacher had to individually answer the survey in relation to each of the subjects they taught. In the Appendix A, Table A4 (a) describes the most important methodological aspects of this questionnaire.

The results of the teacher’s self-assessment questionnaire were presented at the opening session. Therefore, it was a session where most members of GDT from different degrees did not know each other. Before commenting on the results of the questionnaire, participants received a brief training on the fundamentals of the gender dimension in teaching and the four fundamental pillars of the GDT project were presented. The results were shown pillar by pillar and the reactions of bewilderment were very evident. The greatest resistance that could be identified was the lack of an obvious connection between some of the items in the questionnaire and the gender dimension. For example, why does the usefulness of the subject have to do with gender? In contrast, there were aspects in which everyone saw the relationship with gender as participation in the classroom, roles in teamwork, and female referents in the field.

Below are some of the highlights of the responses received by the participating teachers to the questionnaire and the most significant reactions observed at the time of commenting on them. Each of the items corresponds to those shown in Table A1 (Appendix A).

- Contents:

- −

- Eighty-four percent of participants considered that their subject was socially relevant, while only 36% believed that their subject was gender relevant. When asked if the subject included any gender aspect, 90% answered that it did not. This perception did not correspond to reality, as will be seen in the answers to the other items, but responds to the widespread impression that introducing gender into teaching is only introducing gender-related content, leaving aside the other three pillars.

- −

- About the inclusion of female referents in teaching, 58% responded that they did not include any. Sixty-eight percent stated that they had not consulted any recommendation guide for the use of non-sexist language. Regarding gender stereotypes, 77% of the teachers used exercises and examples that did not include gender stereotypes.

- −

- More than half of the teaching staff stated that they did not give students the opportunity to participate in defining the subject. This issue also gave rise to debates, partly because of the apparent incompatibility of the action in groups with a large number of students and partly because of the apparent extra work that this entails. Another detected factor was that participants did not see the relationship of this issue with the gender dimension.

- Methodology:

- −

- Eighty-four percent of the teaching staff considered that their proposed activities did not include gender aspects. Again, it is clear that initially gender is related to teaching only within the content pillar.

- −

- Eighty-seven percent stated that they did not include any conference or video from a female referent in his/her subject. While it is true that 60% of the GDT participating teachers were women and therefore this action is not so relevant because they act as female referents.

- Classroom management:

- −

- Only 26% of the teaching staff analyzed the distribution by gender in group assignments. Nineteen percent of respondents did not know what to answer this question, mainly because in some of their subjects the percentage of male students was extremely high and therefore there was not much to analyze in terms of gender distribution within the groups. It was also discussed whether the teacher should force a particular distribution, e.g., the conditions of the percentage of female students in each group. Regarding this issue, ignorance of students’ real preferences was evident.

- −

- Ninety-four percent stated that they took care of the language used in the classroom and that it was gender inclusive. It is noted that 68% took care that the interventions of the students were free of sexist language. Fifty-eight percent of teachers tried to promote female participation in the classroom and 42% protected such participation from male incursions (such as mansplaining). In the debate on this issue, uncertainties also arose about how to act in the promotion of female participation and even uncertainties about whether the prejudices of GDT members themselves would not condition the perception of reality. Again, there was a lack of quantitative evidence of students’ preferences or behaviors. No general relationship was detected between the teacher’s perception of female participation in the classroom and the teacher’s gender.

- −

- Regarding group work, 68% were aware of the role played by the different team members; but only 19% proposed periodic role changes within the work teams. In relation to this issue, many uncertainties also arose as to how to act.

- Assessment:

- −

- Thirty-two percent did not consider the activities that included gender aspects as evaluable. It is also surprising that the remaining 68% did not know what to answer to this question, mainly because they had never considered that gender issues should also be taken into account in the assessment.

- −

- A large part of the teaching staff provided feedback throughout the course, although this feedback was lower in the individualized case and after the final exam.

- −

- Fifty-eight percent of the teaching staff used the peer co-assessment at some point. This percentage is probably higher than the university average, but, as mentioned before, many of the participants had experience in teaching innovation.

The teachers were convinced of the need for introducing active methodologies in the classroom, carry out projects and case studies, etc. and, therefore, the possibility of introducing gender in these types of activities is suggested. On the contrary, many doubts about classroom management arose. This analysis of strengths and weaknesses helped defining the contents of the subsequent sessions of the GDT project.

One idea that arose from a GDT member during the discussions and with which everyone agreed was that all members had been modeled with the same pattern throughout our training and work experience in the STEM field and that, therefore, in general terms we had the same prejudices and stereotypes. This, along with the certainty that these prejudices may not allow us to see the reality of the classroom, led to the students ’perception questionnaire design and implementation.

3.2. Students’ Perception Questionnaire

The development of this questionnaire was a fully cooperative work [57] and the result can be found at (https://tinyurl.com/yyxpzm59, accessed on 1 April 2021).

In general, consensus among GDT members on what questions should be asked was fairly easy to reach, except at a few specific points. The most critical point was whether we should ask whether the respondent believed that students had different abilities depending on gender. This question arose because of the widespread stereotype in society that women, for example, are less qualified for mathematics than men. Two very different opinions were evident. On the one hand, there was the group of teachers who considered that asking about potential differences based on gender was contrary to the basic principles of equality and was offensive. On the other hand, another group of teachers thought that all possible types of students should be considered and that precisely this question would help to understand the audience we had in the classroom. Finally, the corresponding questions were included in the questionnaire, but the opposition by some teachers and, in particular, by the group of students of the Feminist Assembly of the Barcelona School of Industrial Engineering (ETSEIB), was very evident.

The agreed list of questions was introduced within a common part of the questionnaire designed by each teacher specifically for his/her subject. The questionnaire was distributed among the students at the beginning of the second semester of the 2018/2019 academic year. Each teacher gave a few minutes in the classroom for their response and thus maximize their participation. In the Appendix A, Table A4 (b) shows the most important methodological aspects of this questionnaire.

The questionnaire was filled out by 548 students, which means 55% of the students enrolled in the participating subjects of GDT. From the responses, 56% were obtained from Bachelor degree students and 44% from Master degree students, with 70% of the responses from men and 30% from women (while only 20.7% of students enrolled in the participating subjects of GDT were female). The ages ranged from 18 to 21 years in the case of Bachelor degree students and between 21 and 26 in the case of the Master degree students. The analysis allowed to identify strong and weak points perceived by the students [57]. The most significant points regarding the research questions are discussed below.

One of the most common actions from a gender dimension in teaching and, at the same time, a more immediate implementation is the introduction of female references in the field. The questionnaire was used to identify whether this action was really necessary among UPC students. The results corroborated this, since, although only fifty-four percent of the students had male references, only 24.4% had any female reference. This disproportion is reduced by 10 points when Master degree students are analyzed in isolation, concluding that throughout UPC degrees the students do incorporate some female references in their knowledge. Additionally, the nature of the referents provides a lot of information. Among male students, the male referents were current and international, but the female referents belonged to the personal sphere (family or acquaintances). On the other hand, the majority of the references of the female students, both male and female references, came from the personal sphere.

GDT members, with the perspective acquired over the years, identified the environment of the time of their studies, a STEM field, as a very masculinized environment where female students had to make a place for themselves in the classroom, both in terms of dealing with the teacher and with classmates. There are data that currently the average proportion of female students in the UPC is around 30% and, therefore, it is likely that these feelings are still true for current female students. However, doubts arose as culture in many aspects related to gender has changed over the years and possibly the perceptions of today’s students are different. Therefore, many of the questions in the questionnaire were addressed to how students perceived the relationship with the teacher or even with their peers. The perception regarding gender biases on the part of the teachers was analyzed from different angles: the treatment of the teachers, the language used in the classroom, the images and stereotypes present in the teaching material, the expectations of the teachers and the biases in the evaluation of the students.

The answers to most of the questions in this area were quite different depending on the gender of the student. It seems that male students have a much more homogeneous perception, while female students are divided into two main groups: those who detect bias and those who do not. The percentage of male and female students who detect bias is not insignificant, and therefore reaffirms the need to introduce gender dimension in teaching, especially in classroom management. It is also interesting to note that the average Master degree student detects more prejudice than the average Bachelor degree student.

In Table 2, this behavior, differentiated according to gender, can be detected. These tables show the students’ response to the question about whether they believed that there was a discriminatory treatment by teachers, which is polarized in the case of female students, with 32.52% of female students claiming to have non-specific evidence compared to 56.91% of female students that claim they have some evidence. On the other hand, the response of the male students is more uniform, with only 18.48% claiming to have evidence. The fact of having evidence of discriminatory treatment by teachers should be reflected in the perception that female students encounter difficulties throughout their studies at the UPC. Most male students state the lack of evidence of differentiated treatment by teachers and the belief that female students do not face more difficulties throughout their studies in the UPC. In contrast, the opinion of female students shows a polarized opinion where the percentage of female students who detect discriminatory treatment and difficulties at the same time is significant (the Chi-squared test was applied to each group of questions to determine the corresponding p values; p < 0.05 values indicate that statistically significant differences between both groups do exist).

Table 2.

Responses of male and female students relating the teachers’ treatment to the general female experience of UPC students.

Part of the student body not only perceives a differentiated treatment on the part of the teaching staff, but also on the part of their peers. In fact, 17% of male students and 29% of female students report having observed this biased treatment between equals.

It is noteworthy that 34% of the female students do not feel comfortable participating in class, compared to 11% of the male students. This imbalance is also observed in the interaction between students and teachers outside the classroom. This situation may be caused by all the biases detected or by cultural and stereotyped reasons prior to their studies at the UPC [58]. However, regardless of origin, these differences do not allow female and male students to participate equally in the learning process.

All of these results indicate that the UPC environment is still perceived as a highly masculinized environment and that the barriers identified by GDT members based on their own student experience are still applicable to the current environment and culture.

In addition, these results have reaffirmed some hypotheses of GDT members and have therefore helped a lot in reaching consensus on priority actions.

3.3. Final Assessment Questionnaire

The questionnaire was passed to GDT members during the fifth and final face-to-face session of the project. In the Appendix A, Table A4 (c) shows the most important methodological aspects of this questionnaire.

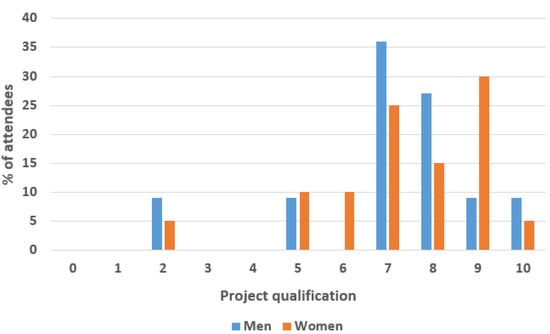

As a GDT post-test, the questionnaire shows us aspects of GDT’s own management and effectiveness in improving participants’ skills in introducing the gender dimension into teaching. Session attendance was found to be reasonably good. Indeed, 97% of teachers attended at least one session and 23% attended all sessions (five sessions). Moreover, 71% attended at least three sessions. With regard to the global satisfaction degree of the project by the participating teachers, Figure 2 shows that the overall assessment of the project is remarkable. In general, GDT members agreed with the content, tasks, and management of the digital information platform.

Figure 2.

Global satisfaction degree of the GDT project by the participating teachers.

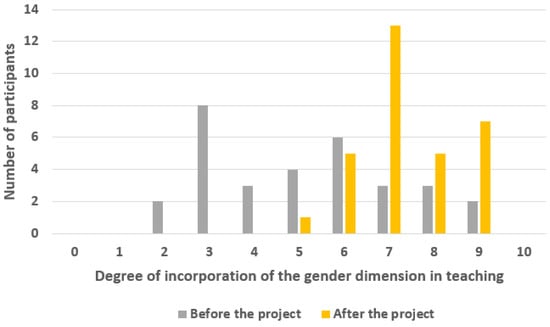

The most relevant aspect of the GDT post-test is the comparison that each GDT member makes about the degree of expertise in incorporating the gender dimension into his/her own teaching before and after the project. Figure 3 shows that the acquisition of skills of teachers is evident.

Figure 3.

Evolution of the degree of incorporation of the gender dimension in teaching of the participating teachers in the GDT project.

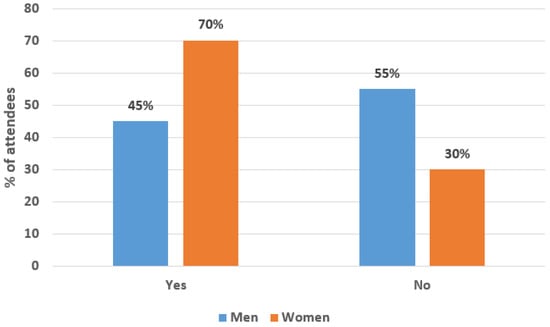

The post-test also includes a question on whether GDT members are able to disseminate the concepts and proposals worked on throughout the GDT to the rest of the UPC community. The results are shown in Figure 4. Most participating women are prepared to begin disseminating the knowledge gained. Men are prepared to a lesser extent. The fact that 70% of women are trained in the dissemination of knowledge is an indicator that a good degree of consensus has been reached throughout the project. However, it is alarming that the proportion of men in these conditions is quite low. This difference could be due, in part, to the still masculinized environment of the UPC where men may find themselves more insecure about showing this new culture to more reluctant colleagues.

Figure 4.

Teacher confidence in disseminating the knowledge acquired in the GDT project (answers to the question “Do you feel ready to disseminate the knowledge acquired in the project?”).

The final questionnaire, apart from being the post-test of the GDT project, serves as an indicator of the consensus reached throughout the project. Recall that in section (III) of the questionnaire, respondents had to prioritize a whole list of actions worked on and carried out throughout the project. The questionnaire has 46 questions, and each question allowed seven possible answers: (1) the action was already applied before GDT and it was not improved with GDT, (2) the action was already applied before GDT, but with GDT has been improved or will be improved, (3) the action has started to be incorporated with GDT, (4) the action will be incorporated soon, (5) the action will be incorporated in the medium/long term, (6) despite the action could be applied in the subject, it will not be applied and (7) the action does not apply in the subject. In the Appendix A, Table A5 includes the main results.

The criterion for defining consensus is not unique and multiple interpretations are possible.

On the one hand, 59% of the questions had a majority answer (more than 50% of the answers matched). However, the fact that a question has, for example, 41.9% of the answers indicating that the action is for immediate application and 25.8% of the answers indicating that it is medium/long term is not contradictory. What does show a high lack of consensus is that an action has 32.3% of responses indicating that it is immediately applicable and that 25.8% of responses are of the ‘Not applicable’ type. If we analyze the answers from this point of view, we can say that only 13% of the questions detect a lack of consensus on the answers. Of this 13%, in all but one question, the second most voted answer is ‘Not applicable’. The only exception in which there is no consensus without opting for a ‘Not applicable’ is the question about the use of various and diverse assessment tools, with 74.2% of the answers indicating that the application is obvious and 12.9% of responses indicate that it will be implemented in the medium or long term. Therefore, with this 74.2%, it can be stated that there is consensus.

In 24% of the questions, ‘Not applicable’ weighs more than 10%, but in no case exceeds 26%. In these questions, we mainly find two groups of actions:

- All the actions in which the students receive greater autonomy, leaving them to choose part of the contents, some subjects of the projects, some questions in the written exam or that the students participate in the design of the assessment process.

- Actions aimed at achieving mixed work teams with non-stereotyped roles. From the discussions of the face-to-face sessions, it can be deduced that the answer ‘Not applicable’ is due to the lack of women in the students and, therefore, to the impossibility of carrying out these actions.

In contrast, in 26% of the questions there was unanimity, understood as a coincidence of more than 70% in the same answer. In all cases, these are actions that participants already applied before starting the GDT project, such as the care of an inclusive language and the care in the response both among peers and by the teacher, avoiding stereotyped images of the teaching material, explaining the usefulness of the subject and the relationship with other subjects, promoting active learning and teaching adaptable to the needs of students, publishing in advance the assessment criteria, using multiple and diverse assessment tools and giving adequate feedback. For the most part, these are generic actions that are not just gender-specific in teaching.

In summary, given that in 59% of the actions analyzed there was an absolute majority in the most voted answer and that in 87% of the actions the two most voted answers were quite similar, it can be stated that a good consensus was reached in prioritizing the actions to be implemented with respect to the gender perspective in teaching.

Once the 46 actions analyzed in the questionnaire had been classified, a classification by levels of these actions was done. A total of four levels of difficulty were defined: Level 0 (fundamental actions), Level 1 (easy-to-apply actions), Level 2 (advanced actions), Level 3 (actions for expertise).

It was the GDT members’ decision that the recommendations guide should have a simple, direct, short and very practical format. The objective is to facilitate its use at the time of designing or modifying subjects by teachers.

This guide is a collection of recommendations for the introduction of the gender dimension (GD) in the STEM teaching. This link shows the guide:

https://tinyurl.com/y5bt4a6n, accessed on 1 April 2021.

3.4. Preferences and Resistances by Teachers

The three main indicators of the study have already been discussed, all in questionnaire format. However, the reactions and contributions of GDT project members, both in face-to-face sessions and in virtual exchanges, continue to provide more information for deciding whether a significant degree of consensus has been reached in identifying relevant actions for the introduction of the gender dimension and its prioritization.

It became clear, especially through the students’ questionnaire, that female participation in the classroom should be further improved, as stated in [46,47]. However, no strategy was identified that was always recommended; quite different scenarios were analyzed, and it became clear that each teacher had to find their own method for specific types of subject and student. Among the actions, it was commented that more time should be allowed students when formulating questions for the class, to explicitly encourage the female students, to respond very positively to the participation of female studens and, above all, to protect them from male interruptions. So much so that there was the case of a female teacher who empowered the female students so much that the male students felt despised and complained.

Another action that teachers usually apply is the introduction of female referents [17]. Referents were introduced in nautical, business management and administration, telecommunications and even computational fluid dynamics. In some of these initiatives, not only were current female referents made visible, but so was the percentage of women in the sector. Different teachers also made an effort to expand the bibliography, trying to include some female authors and, also important, writing their full name so they were not wrongly considered to be male authors.

The greatest resistance evidenced throughout the GDT project was the identification of content directly related to gender. Indeed, introducing gender aspects into the contents of scientific subjects and even technological ones seems, very often, difficult. The cooperative activity carried out in the third face-to-face session of GDT made it possible to identify some relationships between the contents and the gender. For example, they reflected on ergonomics when designing an airplane, safety on the streets, the different perception of safety in the deformation of mechanical structures (i.e., bridges), etc. However, to achieve truly significant success, more sessions and activities would be needed in this direction.

Another resistance identified was the potential perpetuation of gender stereotypes. That is, there is evidence that STEM studies most related to sustainability and communal goals [8,9,10,11,12,13] have a higher percentage of female students enrolled than STEM studies more focused on mechanics, computer science, or civil works, for example. Improving the aspects of sustainability and communal goals on STEM issues can be seen as a perpetuation of stereotypes or as a call for women to gradually feminize the sector. Within the GDT project, we often found ourselves debating this point. Overall, however, there was a consensus to use these still-present differences to attract female students, empower them, and promote change.

Finally, it is noteworthy how there was an absolute consensus on how the resulting guide of the project should be. It was agreed that it should be a concise document, like a checklist and structured in different levels of expertise.

3.5. Research Limitations

The methodology proposed for the research is based on the qualitative and quantitative observations collected throughout the GDT project. However, the GDT project is not without limitations.

Like any teaching improvement process, the results are obtained with an iterative process of design, application, evaluation and improvement to resume the cycle:

- At the teaching level: each participating teacher must continue to introduce the gender dimension in their subject, incorporating more actions and improving their application. This process could be carried out with a more relaxed accompaniment, with some specific work sessions such as coffee breaks, to share experiences and accelerate the process;

- At the institutional level: to repeat the process carried out in GDT project with other teachers and thus extend the network of experts and promote institutional change.

All the work done so far, despite having the support of the institution, has been highly nurtured by the volunteer work of teachers who are aware of the subject, without expecting any compensation and dedicating many extra hours.

It should also be mentioned that the UPC guide obtained as a GDT output is continually evolving. This first version was developed by the team behind the GDT project with the suggestions and comments of all the participating members, but if the process is repeated, it could evolve to incorporate new actions and recommendations.

4. Conclusions

Students must be prepared to learn and develop the skills required by the technologies of the 21st century. These changes will educate students as citizens of a more sustainable future in terms of equity, inclusion, diversity, prosperity and justice, key aspects included in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Gender diversity is a fundamental pillar in education in order to raise awareness about gender stereotypes and promote attitudinal changes in students.

The GDT project is the framework for cooperative work to identify and prioritize actions for the introduction of gender dimension in teaching.

The response from the teaching community to the call for the GDT project was excellent, with the participation of 8 STEM Bachelor and Master degrees and a total of 41 teachers initially enrolled.

A teacher self-assessment tool was created as a starting point for cooperative work. Once reviewed and documented, it was made available to the whole university community to detect possible improvements in the introduction of the gender dimension in the subjects.

A questionnaire was also designed for the analysis of the degree of gender issues awareness among students. The questionnaire allowed us to corroborate the hypotheses of GDT members about the UPC environment regarding possible biases in teaching. Key points were identified such as classroom management that helped create greater consensus among GDT faculty. This questionnaire can be applied in the first and last year of studies as an indicator in the analysis of the introduction of the gender dimension in a transversal way in higher education studies.

Additionally, within the framework of GDT, a final assessment questionnaire of the project was generated, which marked the prioritization for the elaboration of a guide of the UPC for the incorporation of the gender dimension in teaching. This guide responds to a social and also normative need. On the one hand, engineering, science and architecture aim to respond to the needs of society, and therefore to the needs of women and men. To do so, they need to be nurtured equally by the vision and values of both genders. On the other hand, the Spanish Law 17/2015, of 21st July, on the effective equality of women and men of Catalonia in Spain paved the way for the General Framework for the Incorporation of the Gender Dimension in Higher Education of the AQU. In this new framework, Catalan universities must take measures for the transversal incorporation of the gender dimension in all higher education.

The GDT project has highlighted the possibility of reaching a consensus on most actions to be implemented to achieve a gender dimension. The most immediate and gender-specific actions in which there is a greater consensus include the introduction of female referents, the revision of teaching material in order to eliminate stereotypes in images or sentences, and the revision of the language used by everyone in the classroom. In addition, in the analysis of the questionnaire to the students, evidence was obtained of the need to apply these actions.

The actions in which there is more resistance on the part of the teachers correspond to actions in which the students participate more actively in the design of the subject.

Two critical points have also been identified: (1) the fear of perpetuating stereotypes if used to bring teaching closer to female students and (2) the difficulty in identifying the contents of STEM subjects where gender has a relevant role.

Finally, a network of contacts between teachers has been created for future collaborations and the know-how of the teaching staff regarding the introduction of the gender dimension in STEM teaching is being substantially expanded.

The authors believe that this methodology based on a cooperative project can be replicated in other centers and institutions in order to reach a consensus among the participating members and serve as a reference for institutional change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all the authors; methodology, all the authors; software, M.P. and N.O.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P. and N.O.-T.; writing—review and editing, all the authors.; supervision, M.P. and E.M.d.l.V.; funding acquisition, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work and the APC were funded by GEECCO project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 741128.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials available on request from the authors: The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the members of the Gender Dimension in Teaching project carried out at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya along 2018/2019 academic year and to students who participated in the surveys for their cooperation. This work was carried out within the framework of the Gender Dimension in Teaching project at Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official point of view of the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya nor the European Commission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Classification of the pillars of the GDT project.

Table A1.

Classification of the pillars of the GDT project.

| Interdisciplinarity | Self-Concept | Capacities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contents | Usefulness of the subject for students. Relation of the subject with other subjects. Social relevance of the subject. Gender relevance of the subject. Social aspects of the subject. | Inclusion of female references. Consultation guide of recommendations for the use of non-sexist and androcentric language. Use of non-sexist language Inclusion of images with gender stereotypes. Inclusion of exercises and examples with gender stereotypes. | Opportunities for student participation in defining the subject. Application of knowledge by students on topics of interest to them. |

| Methodology | Active learning. Inclusion of gender aspects in active learning. Recommendations for the preparation of scientific documents. | Inclusion of lectures or videos of female references. Channel to make gender actions visible. | Carrying out a survey to quantify awareness in the subject. Modification of teaching based on the results of the previous survey. Feedback with peers to improve teaching. |

| Classroom management | Detection of different behaviours in students according to gender. Analysis of the distribution by gender in the working groups. | Care and inclusion of language by the teacher. Care and inclusion of language by students. Control of participation by gender. Promotion of female participation. Protection of female participation from male incursions. Tolerance to student comments. | Detection of roles of different team members in group work. Empowerment of women in teamwork. |

| Assessment | Assessment of activities that include gender aspects. Information to students about the assessment criteria. Inclusion of different activities in the assessment of the subject. Use of diverse assessment typology. | Feedback to the class group. Individual feedback. Feedback after the final exam. | Use of co-assessment between peer groups. Option to give students their own assessment typology. |

Table A2.

Participating teams of the GDT project.

Table A2.

Participating teams of the GDT project.

| School/Faculty | Bachelor/Master Degree | Covered Courses | Involved Teachers | Involved Students |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castelldefels School of Telecommunications and Aerospace Engineering | Bachelor degree in Aerospace Systems Engineering | Meteorology Fundamentals of physics Mechanics Biophysics Fluid mechanics | 5 | >500 |

| Barcelona School of Architecture | Bachelor degree in Architecture | Architecture workshop Projects VI Urban planning I Urban planning II | 3 | >200 |

| Barcelona School of Civil Engineering | Bachelor degree in Civil Engineering | Urban planning Differential geometry and differential equations Environmental engineering Probability and statistics | 10 | >200 |

| Barcelona School of Industrial Engineering | Master degree in Industrial Engineering | Industrial engineering Business administration Technological innovation Description and improvement of processes Management and cost control | 6 | >500 |

| Barcelona Faculty of Nautical Studies | Double Bachelor degree in Naval Systems and Technology Engineering | Fluid mechanics Maritime technical English Naval and mechanical Technology Ship theory Quality, safety, environment and sustainability management | 6 | >150 |

| Barcelona School of Industrial Engineering | Master degree in Environmental Pathways for Sustainable Energy Systems (SELECT, Kic InnoEnergy) | Energy and environment Energy resources Oral and written communication | 3 | >50 |

| Barcelona School of Telecommunications Engineering | Master degree in Applied Telecommunications and Engineering Management (MASTEAM) | Master Thesis Project on ICT-based business models ICT-based entrepreneurship Next-generation wireless communications 5G Network planning | 5 | >100 |

| Manresa School of Engineering | Bachelor degree in ICT Systems Engineering | Complementary technologies 1 Complementary technologies 2 Mathematical foundations for ICT Databases Statistics Project management | 5 | >150 |

Table A3.

Description of the sessions of the GDT project.

Table A3.

Description of the sessions of the GDT project.

| Session | Date | Objectives | Scope | Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous session | December 2018 | A tool for self-assessment of the gender dimension in teaching for teachers was developed. | To know the gender perceptions of the participation teachers. | Answer, by the teachers, to the preliminary self-assessment questionnaire on the degree of introduction of the gender dimension in teaching. |

| 1 | 2019/01/18 | The objectives, work schedule and training on gender and teaching were presented, with examples inside and outside at the University. | The theoretical and practical bases for the development of the project were provided. | 1. Analysis of the form answered online regarding the experience of the team. This lead to a discussion on the real needs of students and our pre-judgements. 2. Presentation of the pre-test concept. |

| 2 | 2019/02/05 | The objectives of each work team were reviewed. These include promoting the participation of female students in the classroom, the introduction of female references, the revision of teaching material, the definition of more contextualized evaluations, etc. | Participants worked together to propose pre-test questions. | 1. Prior to session 2 all participants should have to define the gender action to be applied in their subjects, the pre-test questions and the indicators for the assessment. 2. Decision: include in the pre-test some questions to confirm our hypothesis about student’s needs and present situation. 3. A pre-test and a post-test were designed and sent to the students at the beginning and at the end of the term. |

| 3 | 2019/03/15 | After showing and analyzing the results of the pre-test, a group work was carried out, interspersing teachers from different fields in order to visualize the social and gender relevance of all subjects, from the most applied to the most theoretical. | The partial results of the pre-test and the indicators selected to achieve the objectives were analyzed. | Teamwork activity: mixed groups had to answer questions related to 4 aspects: 1. What is being taught and why? 2. Which is the utility of what is being studied, who is the beneficiary and how can we increase their benefits, does these benefits depend on the gender? 3. Which is the data required for the study, and its origin, do they depend on the gender? 4. Are there any different strategies to analyze it? which is the criteria for choosing one or another? does it depend on gender? A form for each subject was defined where the goals, the indicators and the gender relevance was made explicit. |

| 4 | 2019/04/25 | The different experiences on evaluation and their results depending on the gender were analyzed. | A collection of subjects with relevant activities from a gender dimension was prepared. | 1. Presentation of the state of the art regarding gender and evaluation. 2. Discussion according to our experiences. 3. A new form regarding the subjects were the introduction of a gender dimension is straightforward was defined. |

| 5 | 2019/06/07 | The different experiences were analyzed, thus collecting the indicators on the effectiveness of the project. | A collection of recommendations, subject sheets and post-test results were analyzed, and priority subjects were identified to apply the gender dimension in each degree. | A new workgroup appeared in order to further improve the questionnaire on the perception of the gender dimension of the students. |

Table A4.

Most important design aspects of the: (a) Teacher’s self-assessment questionnaire, (b) Students’ perception questionnaire, (c) Final assessment questionnaire.

Table A4.

Most important design aspects of the: (a) Teacher’s self-assessment questionnaire, (b) Students’ perception questionnaire, (c) Final assessment questionnaire.

| Survey | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Descriptive statistical. Non-probability sampling by judgment or opinion. | |

| Population | (a) | Teachers participating in the project |

| (b) | Students enrolled in the subjects participating in the project | |

| (c) | Teachers participating in the project | |

| Survey period | (a) | January 2019 |

| (b) | 2018/2019, Q2 | |

| (c) | June 2019 | |

| Sample | (a) | 41 teachers |

| (b) | 548 students | |

| (c) | 41 teachers | |

| Process | Survey anonymous online | |

| Data collection instruments | Google Forms® | |

| Data analysis instruments | IBM SPSS v19 Solutions for Education® |

Table A5.

Classification of answers in the Final assessment questionnaire of the GDT project.

Table A5.

Classification of answers in the Final assessment questionnaire of the GDT project.

| Obvious | Immediate | Medium/Long Term | Never | Not Applicable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Make the utility explicit | 83.9% | 12.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 2 | Make the social relevance explicit | 41.9% | 51.6% | 6.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 3 | Make the relevance of gender explicit | 22.6% | 64.5% | 9.7% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 4 | Explain the relationship with other subjects | 87.1% | 3.2% | 9.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 5 | Teaching guide: sustainability and social commitment competence | 29.0% | 45.2% | 19.4% | 0.0% | 6.5% |

| 6 | Teaching guide: objectives with social and/or gender relevance | 22.6% | 48.4% | 22.6% | 0.0% | 6.5% |

| 7 | References of female authors and/or female professionals | 32.3% | 58.1% | 9.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 8 | References with full name | 22.6% | 58.1% | 12.9% | 3.2% | 3.2% |

| 9 | Non-sexist or androcentric language | 74.2% | 25.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 10 | Images without stereotypes | 71.0% | 29.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 11 | Examples and exercises without stereotypes | 51.6% | 32.3% | 9.7% | 0.0% | 6.5% |

| 12 | Context with different themes | 58.1% | 32.3% | 6.5% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 13 | Students participate in the contents | 45.2% | 16.1% | 22.6% | 0.0% | 16.1% |

| 14 | Active learning | 93.5% | 3.2% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 15 | Projects: students choose a theme | 58.1% | 9.7% | 16.1% | 3.2% | 12.9% |

| 16 | Projects: with social and/or gender relevance | 32.3% | 35.5% | 25.8% | 0.0% | 6.5% |

| 17 | Case study: relevant woman | 12.9% | 41.9% | 25.8% | 0.0% | 19.4% |

| 18 | Guidelines for nonverbal oral communication | 67.7% | 9.7% | 9.7% | 0.0% | 12.9% |

| 19 | Conference or video of a female referent | 16.1% | 41.9% | 29.0% | 0.0% | 12.9% |

| 20 | Activities: explain the social and/or gender relevance | 35.5% | 38.7% | 19.4% | 0.0% | 6.5% |

| 21 | Gender pre-test and post-test | 9.7% | 64.5% | 22.6% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 22 | Comment on pre-test and post-test results | 6.5% | 64.5% | 25.8% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 23 | Teaching adapted to interest and needs | 74.2% | 25.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 24 | Language guidelines in oral and written communications | 48.4% | 38.7% | 6.5% | 0.0% | 6.5% |

| 25 | Gender debate | 9.7% | 35.5% | 35.5% | 9.7% | 9.7% |

| 26 | Analysis of participation imbalances | 45.2% | 38.7% | 9.7% | 0.0% | 6.5% |

| 27 | Promote female participation | 58.1% | 32.3% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 6.5% |

| 28 | Protect from male incursions | 51.6% | 35.5% | 0.0% | 3.2% | 9.7% |

| 29 | Take care of your own response | 80.6% | 16.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 30 | Teacher: inclusive and non-sexist language | 83.9% | 12.9% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 31 | Students: inclusive and non-sexist language | 58.1% | 38.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 32 | Distribution by gender in teamwork: analyze and make explicit | 38.7% | 32.3% | 6.5% | 3.2% | 19.4% |

| 33 | Distribution of roles in teamwork: analyze and make explicit | 29.0% | 35.5% | 16.1% | 0.0% | 19.4% |

| 34 | Promote roles in teamwork | 19.4% | 32.3% | 19.4% | 3.2% | 25.8% |

| 35 | Empowerment of female students in teamwork | 45.2% | 32.3% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 19.4% |

| 36 | Accessibility outside of class hours | 96.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 37 | Assessment of activities with gender dimension | 12.9% | 41.9% | 29.0% | 0.0% | 16.1% |

| 38 | Publish assessment criteria in advance | 77.4% | 12.9% | 3.2% | 3.2% | 3.2% |

| 39 | Multiple and various assessment instruments | 74.2% | 9.7% | 12.9% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 40 | Co-assessment | 45.2% | 19.4% | 19.4% | 6.5% | 9.7% |

| 41 | Non-unique written exam question format | 67.7% | 12.9% | 6.5% | 0.0% | 12.9% |

| 42 | Contextualize the statements–social and/or gender relevance | 38.7% | 29.0% | 22.6% | 3.2% | 6.5% |

| 43 | Analysis of results disaggregated by gender | 22.6% | 41.9% | 22.6% | 3.2% | 9.7% |

| 44 | Adequate feedback | 77.4% | 9.7% | 9.7% | 0.0% | 3.2% |

| 45 | Formative assessment in the final exam | 64.5% | 12.9% | 9.7% | 3.2% | 9.7% |

| 46 | Students participate in the assessment process | 19.4% | 16.1% | 29.0% | 9.7% | 25.8% |

References

- Caprile, M.; Palmén, R.; Sanz, P.; Dente, G. Encouraging STEM Studies for the Labour Market, European Parlament. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/542199/IPOL_STU(2015)542199_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Segovia-Pérez, M.; Castro Núñez, R.B.; Santero Sánchez, R.; Laguna Sánchez, P. Being a woman in an ICT job: An analysis of the gender pay gap and discrimination in Spain. New Technol. Work Employ. 2020, 35, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenduc, G. Not a Job for Life? Women’s Progression, Conversion and Dropout in ICT Professions. Int. J. Gender, Sci. Technol. Spec. Issue Women ICT 2011, 3, 483–500. [Google Scholar]

- Benavent, X.; de Ves, E.; Forte, A.; Botella-Mascarell, C.; López-Iñesta, E.; Rueda, S.; Roger, S.; Perez, J.; Portalés, C.; Dura, E.; et al. Girls4STEM: Gender diversity in STEM for a sustainable future. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, E.; Sapienza, P.; Zingales, L. How stereotypes impair women’s careers in science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4403–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmedo-Torre, N.; Sanchez Carracedo, F.; Salan Ballesteros, M.N.; Lopez, D.; Perez-Poch, A.; Lopez-Beltran, M. Do female motives for enrolling vary according to STEM profile? IEEE Trans. Educ. 2018, 61, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltà, R.; Olmedo-Torre, N.; Peña, M. Do students from underrepresented groups feel integrated into engineering degrees? In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Education-Education for a Sustainable Future, Uppsala, Sweeden, 21–24 October 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]