The 10 Most Crucial Circular Economy Challenge Patterns in Tourism and the Effects of COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Circular Economy

2.2. Circular Tourism

3. Systematic Literature Review

- (1)

- Macroenvironmental level refers to the elements that, from the company’s perspective, cannot be changed. We used the well-known PESTEL framework [53,54] encompassed by the following elements and their abbreviations: political (P), economic (E), social (S), technological (T), environmental (EN), and legal (L).

- (2)

- Microenvironmental level is defined as the factors that are external to the company but which belong to its industry. We differentiated between resources (R) that a company can purchase within its business environment (such as human, financial, physical, and intellectual resources on their respective markets), value chain (VC), defining the relationship between the different players within an industry, and infrastructure (I) that is established and can be leveraged by the players of the industry (such as roads, internet network, waste management systems, etc.).

- (3)

- Organizational level refers to the factors inside the company. Here we leveraged three different frameworks that build upon each other to represent the different layers of abstraction from an organizational perspective. At the highest level, the ordering moments describe the coherent orientation and meaning of a company [55] and cluster the challenges related to the structure (STR), strategy (STRAT), and culture (CULT) of the company. At the middle level, the business model canvas [56] describes the core elements of the business logic of a company consisting of nine building blocks such as key partners (KP), key activities (KA), key resources (KR), value propositions (VP), customer relationship (CUSTR), customer segments (CUSTS), channels (CH), cost structure (CS), and revenue streams (RS). At the lowest level, the EMF systems diagram maps the looping actions derived from a circular business model and differentiates between the biological cycle (BC) or the technical cycle (TC).

4. Methodology

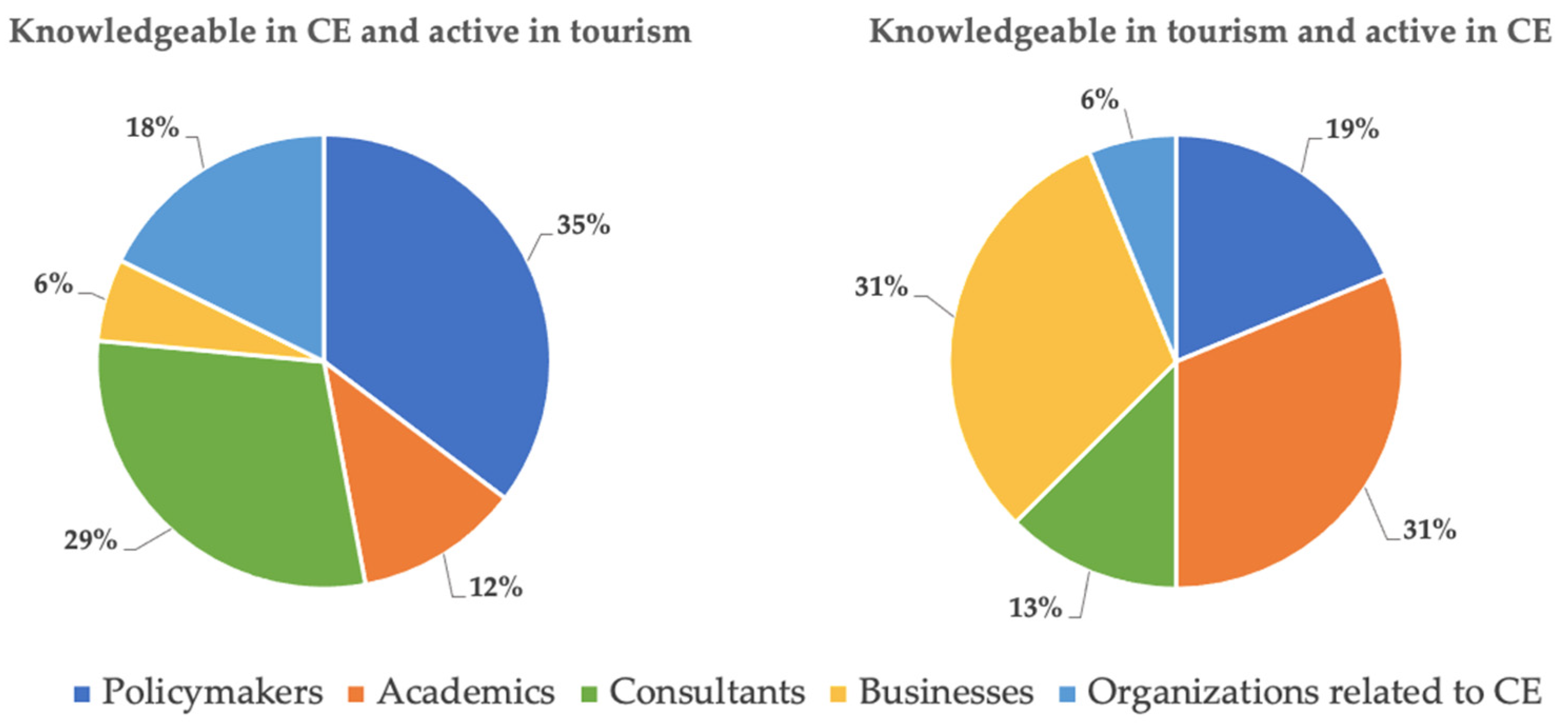

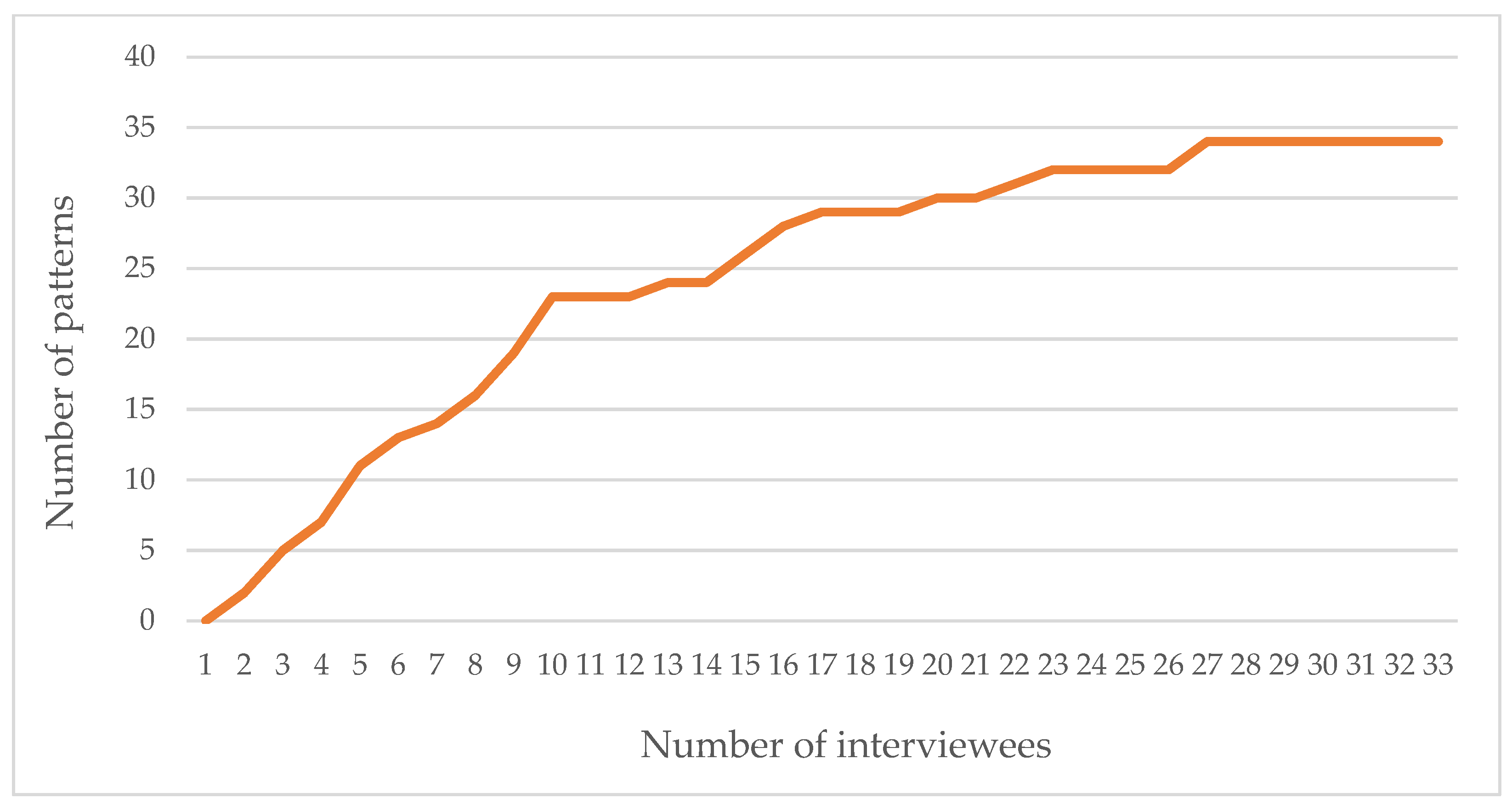

4.1. Data Collection

4.2. Data Analysis

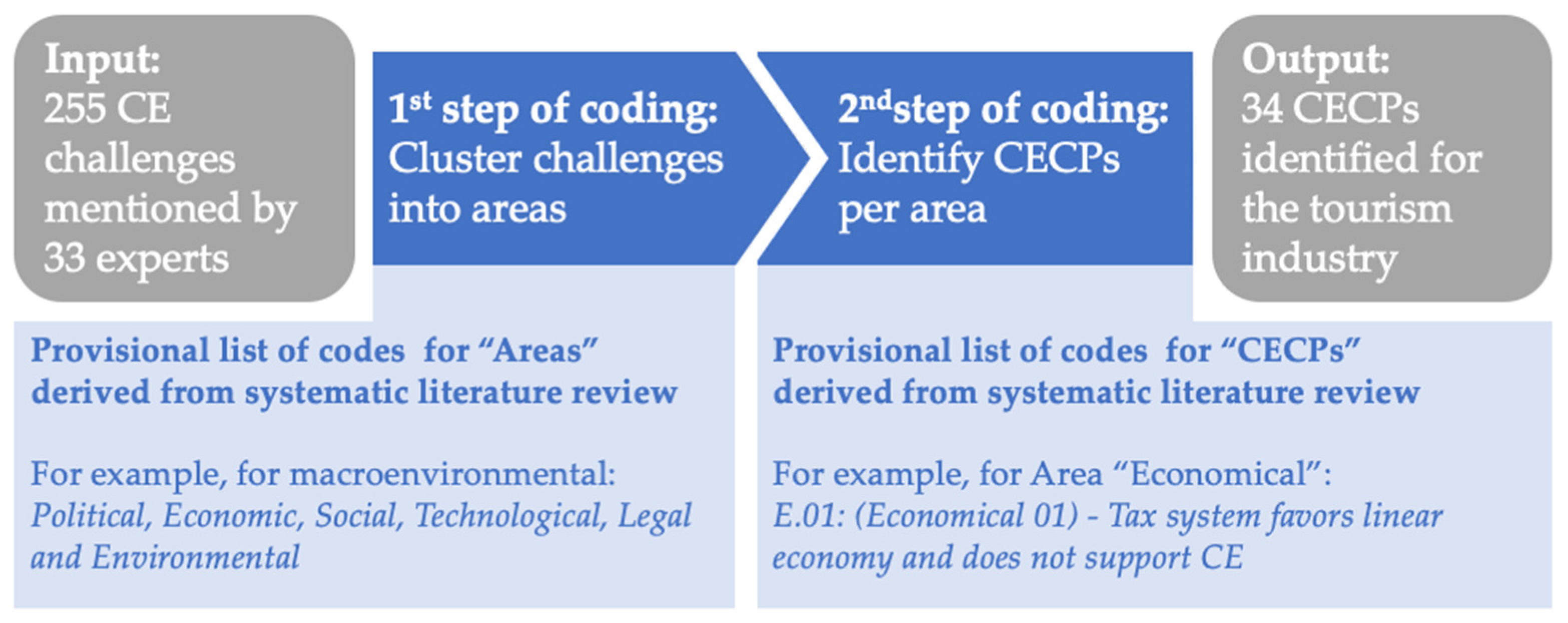

4.2.1. Phase 1: Identification of CECPs Applicable to the Tourism Industry

4.2.2. Phase 2: Specificity for Each Identified CECP in the Tourism Industry

- (1)

- First, we leveraged the description of the analyzed CECP from the systematic literature (an example is illustrated in Section 5.1, Table 4, second column “explanation of CECP in the literature”). We used open coding to identify the different ideas that the description encompassed.

- (2)

- Second, we used open coding to converge the challenges mentioned by the interviewees that were mapped to the analyzed CECP to identify the different ideas that the interviews encompassed. We continued converging until we reached the same level of abstraction of the ideas from the CECPs descriptions.

- (3)

- Third, we leveraged the ideas of the CECP description from the systematic literature review as provisional lists of codes to evaluate which ideas from the interviews matched. When more than 50% matched, we defined the CECP as having a low specificity and otherwise as having a high specificity.

4.2.3. Phase 3: Identification of Negative COVID-19 Effects for CECPs in Tourism

5. Results

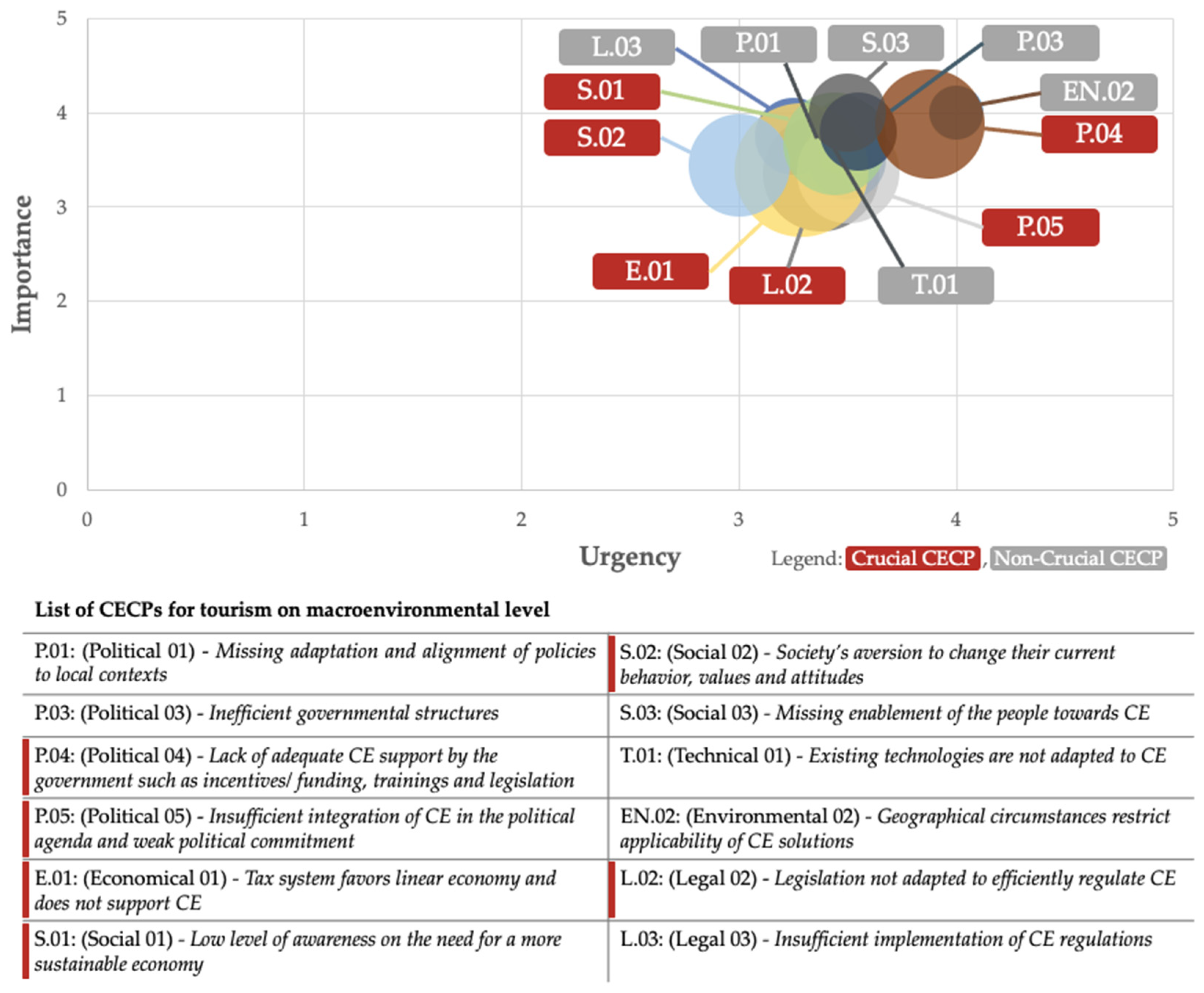

- Title of CECP: Identifier of the CECP, as well as the corresponding title

- Area: Element of the corresponding framework leveraged to group the CECPs

- Level of specificity: Whether the specificity is low or high

- Average importance: Giving the average of the importance provided by the interviewees

- Average urgency: Giving the average of the urgency provided by the interviewees

- Frequency of specific CECP: Stating how many experts from the 33 interviewed have named the CECP.

5.1. Macroenvironmental Level

5.2. Microenvironmental Level

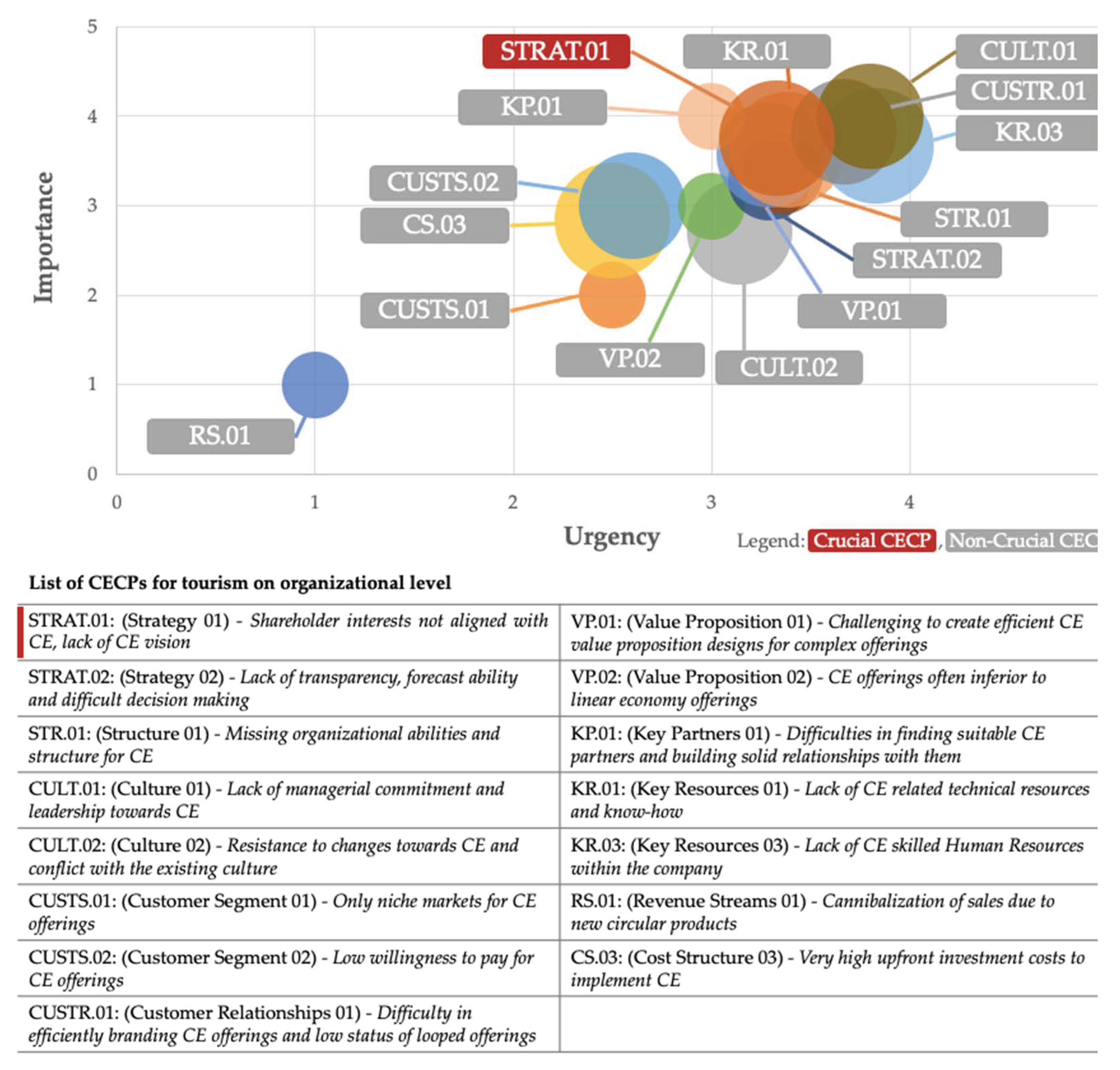

5.3. Organizational Level

5.4. Negative Effects of COVID-19 on Certain CECPs

6. Discussion

6.1. How can the Understanding of the 10 Most Crucial CECPs Help Tourism Practitioners to Move the Industry toward CE?

6.1.1. How Pursuing Goal 1, “Stimulate Design for the Circular Economy”, Helps Tackle the Crucial CECPs in Tourism

6.1.2. How Pursuing Goal 2, “Manage Resources to Preserve Value”, Helps Tackle the Crucial CECPs in Tourism

6.1.3. How Pursuing Goal 3, “Make the Economics Work”, Helps Tackle the Crucial CECPs in Tourism

6.1.4. How Pursuing Goal 4, “Invest in Innovation, Infrastructure, and Skills”, Helps Tackle the Crucial CECPs in Tourism

6.1.5. How Pursuing Goal 5, “Collaborate for System Change”, Helps Tackle the Crucial CECPs in Tourism

6.2. How Should We Further Develop the Research Field on CE Based on the Findings for the Tourism Industry?

6.3. What Can We Learn from the Negative Effects of COVID-19 to Make CE Endeavors More Resilient to Future Pandemics?

7. Conclusions

- (i)

- Policymakers should especially focus on the macroenvironmental level, as six out of the 10 most crucial CECPs have been mapped to this level. Within the political area, policymakers need to establish adequate CE support to tackle “P.04: (Political 04)—Lack of adequate CE support by the government such as incentives/funding, trainings and legislation” and make CE a more prominent topic within political parties to tackle “P.05: (Political 05)—Insufficient integration of CE in the political agenda and weak political commitment”. Within the economic area, policymakers need to rethink the mechanisms of our current tax system to tackle “E.01: (Economic 01)—Tax system favors linear economy and does not support CE”. Within the social area, policymakers need to invest in CE marketing campaigns to tackle “S.01: (Social 01)—Low level of awareness on the need for a more sustainable economy” and “S.02: (Social 02)—Society’s aversion to change their current behavior, values and attitude”. Within the legal area, legislation need to be reviewed to tackle “L.02: (Legal 02)—Legislation not adapted to efficiently regulate CE”.

- (ii)

- The second most important level to focus on is the microenvironmental level that encompasses three out of the 10 most crucial CECPs for the tourism industry. Especially, knowledge on how to efficiently transition toward and operate in a CE needs to be further developed and made available within the industry to tackle “R.05: (Resources 05)—Lack of proof of solid CE theory, concepts, methods, measurements and role models (especially business models)”. Furthermore, policymakers need to promote collaboration between the players in the tourism value chain to tackle “VC.03: (Value Chain 03)—Lack of willingness and trust to collaborate across the value chain”. Additionally, a solid waste management infrastructure is needed for the tourism industry to tackle “I.02: (Infrastructure 02)—Inefficient waste management/recycling systems, practices and infrastructures”.

- (iii)

- At this stage of the transition toward a circular tourism model, the organizational level is perceived as the least important to focus on by the interviewees as only one of the 10 crucial CECPs for the tourism industry has been mapped to this level. However, we believe that this CECP is a crucial one that should not be overlooked. Policymakers need to evaluate through which mechanisms it can be attractive for tourism mechanisms to move toward a circular tourism model to tackle “STRAT.01: (Strategic 01)—Shareholder interests not aligned with CE, lack of CE vision”.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Meta Data on CECPs | Explanation of CECP in the Literature | Specificities for the Tourism Industry |

|---|---|---|

| Title of CECP: P.01: (Political 01)—Missing adaptation and alignment of policies to local contexts Area: Political Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.75 Average urgency: 3.50 Frequency of specific CECP: 4 experts | There is a lack of harmonization between the policies applied at an international, national, and local level. The regional policies are not adapted to the local contexts and the sustainability goals of cities are sometimes in conflict with national priorities. “Regional policies not calibrated to local contexts” [79] (p. 7). Articles: [79,80,81,82,83]. | Tourism is characterized by highly heterogeneous offerings highly dependent on the regional and municipal characteristics and on their degree of vulnerability (balance between the economic activity and the environmental pressure). CE policies need to be adapted to the regions and municipalities. To illustrate one example mentioned, if you have a region that is characterized by nomadic tourism and the waste collection infrastructure is underdeveloped, then the CE policies should include a ban on certain disposable items, such as plastics bottles, which are typically associated with nomadic activities. |

| Title of CECP: P.03: (Political 03)—Inefficient governmental structures Area: Political Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.75 Average urgency: 3.50 Frequency of specific CECP: 4 experts | The bureaucracy blocks company’s application of sustainability policies and legislations. There is a lack of decentralization of decision-making and lack authority to effect change. “Cities lack the institutional capacity to deliver looping actions across resource types” [80] (p. 11). Articles: [79,80,82,84,85,86,87,88,89,90]. | The focus was primarily on the unnecessary bureaucratic procedures that put the tourism industry to a halt when moving toward circularity. No tourism specifications were highlighted by the experts. |

| Title of CECP: P.04: (Political 04)—Lack of adequate CE support by the government such as incentives/ funding, trainings and legislation Area: Political Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.88 Average urgency: 3.88 Frequency of specific CECP: 8 experts | Lack of CE support by the government in the form of few financial incentives, training, CE policies (such as for public procurement). “The lack of funding opportunities likely relates to the unclear market demand for CBMs” [91](p. 6). Articles: [11,12,15,73,74,79,80,84,86,87,91,92,93,94,95,96]. | Experts insisted that the most important challenge linked to government support is the lack of financial incentives established for tourism organizations (in particular SMEs) to become more circular. One specific point mentioned is that, specifically for the case of the EU, there are a lot of funds available for becoming more circular (such as Horizon2020, COSME), but the SMEs do not have the time and the expertise to understand the complex process for applying to these funds. So even though funds are theoretically available, they are practically not reachable for tourism SMEs, which represent the majority of tourism businesses. Additionally, one expert argued that the government should force OTAs (Online Travel Agencies) by legislation to show clearly the level of circularity of different offers (e.g., Booking.com could be obliged to show the water consumption levels of hotels per year, how hotels and apartments manage their waste, etc.) This would put pressure on the accommodation businesses to become more circular while ensuring transparency for the tourists caring about circular offers. |

| Title of CECP: P.05: (Political 05)—Insufficient integration of CE in the political agenda and weak political commitment Area: Political Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.37 Average urgency: 3.50 Frequency of specific CECP: 7 experts | The silo-mentality within governments hinders the implementation of a circular economy. Lack of strong policy maker’s commitment and support for sustainability issues. There is a lack of integrated approach for policymaking and deficient institutional frameworks. Energy-saving and pollution reduction conflicts with GDP due to limited attention by national and regional governments. “Lack of political initiatives supporting CE tourism innovation” [20] (p. 3). Articles: [6,11,20,73,74,79,80,84,88,96,97,98,99]. | The only specificity mentioned is that politicians are not fully aware of the impacts caused by the tourism industry, which in turn does not create the willingness to focus on the tourism industry to become more circular. |

| Title of CECP: E.01: (Economical 01)—Tax system favors linear economy and does not support CE Area: Economic Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.37 Average urgency: 3.31 Frequency of specific CECP: 12 experts | Tax systems are not aligned with CE (e.g., high taxes on waste, lack of taxation of labor rather than raw materials…). This unfavorable tax environment leads companies to avoid the implementation of CE, although they are willing to do so. “Existing taxation systems, policies as well incentives, are not aligned with the adoption of the CE paradigm” [100] (p. 7403). Articles: [20,73,79,86,91,97,98,100]. | Experts highly criticized the current linear tax systems that are affecting the possibilities to circulate the tourism industry. First, regarding transportation, experts pointed out that taxation on aviation fuels is flawed, because the externalities are not internalized. The problem is that if taxes would be adequately applied to energy, tourism would decrease, and communities highly dependent on tourism would be worse-off and oppose. Second, other experts mentioned that it is cheaper to incentivize linear behaviors than circular ones (i.e., throwing the organic waste to landfill instead of sorting it to incorporate it back to the tourism value chain in the form of compost). Another example mentioned was related to secondhand furniture being more expensive than brand new. This makes it prohibitive to switch toward circular economy procurement strategies, thus demotivating tourism stakeholders to be circular, and puts a lot of environmental pressure by incentivizing a “take-make-waste” model. Third, even though implementing a green tourism tax (direct or indirect) to the tourists can be a great way to compensate the negative impacts created and promote a different kind of tourism with a higher purchasing power, it is perceived as detrimental for the tourism sector in some destinations such as the Canary Islands, as it can affect the path dependency of mass tourist customers, which are an important segment of the tourists coming. Fourth, taxes need to stop being visitor volume growth-oriented to incentivize a certain type of tourism that is better for the environment and for the economy (longer stays), e.g., cycle tourism. |

| Title of CECP: S.01: (Social 01)—Low level of awareness on the need for a more sustainable economy Area: Social Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.67 Average urgency: 3.44 Frequency of specific CECP: 7 experts | Consumers are not aware of the importance of CE, which makes it difficult to adopt sustainable practices. Consumers do not see the urgency of changing their habits for the benefit of the environment, society, and the economy. In addition, the awareness among logistic companies and producers is still too limited to trigger a large-scale shift toward a CE. “Need to raise awareness on the impact of ‘habitual choices’ on environmental, social, political and cultural system” [81] (p. 2201). Articles: [11,15,73,74,79,80,81,82,83,84,86,95,96,101,102,103]. | Lack of awareness on CE among tourists and employees in the tourism sector is seen as a challenge when moving toward CE. On the one hand, tourists are less aware of their behaviors when on holidays as to when they are at home. Therefore, it is crucial to raise the awareness of tourists to change their customer travel and consumption patterns toward more circular ones, particularly in developed places with a good waste infrastructure, to fight the core problem of overconsumption. Because it does not impact us in the same way, as we cannot see the big picture of the amounts of waste generated by our consumption and travel habits. On the other hand, employees in the tourism sector have low levels of awareness and understanding, varying between developed and developing countries, on the opportunities and benefits that circularity can bring in tourism and how it can be implemented. For example, in some countries such as South-East Asia, using single-use plastics is preferable as it is a sign of wealth no matter the environmental impacts it can cause related to, e.g., its improper disposal due to deficient waste management infrastructures. |

| Title of CECP: S.02: (Social 02)—Society’s aversion to change their current behavior, values and attitudes Area: Social Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.44 Average urgency: 3.00 Frequency of specific CECP: 7 experts | There is a rigidity in consumer behavior toward change in their habits. The existing values, norms, and lifestyles may hinder the implementation of a CE, as there is little or no willingness to change their behavior and consumption patterns; customers usually question the quality, health, and safety of reused and remanufactured products and tend to have the wrong perceptions on them. Hence, this lack of willingness to buy used products forces the remanufacturers to not go for refurbishing/remanufacturing. “Lack of customer interest in the environment” [94] (p. 1055). Articles: [6,20,74,79,80,83,88,93,94,98,99,101,102,104,105]. | In general, tourists tend to care less and tend to leave behind their “circular” attitudes when on holidays. Experts have mentioned two major issues that explain this. The first one is the “convenience factor” when traveling, particularly with hand luggage, which is a priority over everything else. The second one is the difficulties in adapting to the different waste systems at every destination they go due to the lack of information, which leads, in turn, to less interest in its proper disposal. For example, in one city, plastics go in one place and paper goes in another place, but it might be that because of the production system at the holiday destination that they put plastic and paper together. |

| Title of CECP: S.03: (Social 03)—Missing enablement of the people towards CE Area: Social Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 4.00 Average urgency: 3.50 Frequency of specific CECP: 4 experts | There is a lack of understanding of CE among many players in society due to education deficiency on CE. Waste topic is not included sufficiently in school curricula, hindering the enablement of children from taking more circular actions. Low rates of recycling in society are related to a lack of proper education on environmental issues. “Lack of availability of environmental management programs and facilities both under governmental bodies and at academic institutions” [73] (p. 10). Articles: [73,75,79,90,98,99,106]. | The experts emphasized the need to implement system thinking approaches through education of the different stakeholders involved in tourism. No tourism specifications were highlighted by the experts. |

| Title of CECP: T.01: (Technical 01)—Existing technologies are not adapted to CE Area: Technological Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.50 Average urgency: 3.50 Frequency of specific CECP: 4 experts | Technology for CE is not available at scale at a cost-effective level. There is currently limited proof for CE technology. There are many technological limitations for the tracking of recycled materials due to the increasing complexity of products, which make them effective and efficient recovery and reuse of products and components a massive challenge. “Lack of adequate technologies used in landfilling and incineration activities cause huge irrevocable environment losses” [73] (p. 11). Articles: [6,73,74,75,79,83,84,86,93,97,98,101]. | This challenge was tackled by focusing on the lack of technologies (such as blockchain and big data) to implement selective waste sorting in origin in order to leverage the organic waste generated across the tourism value chain for other uses. |

| Title of CECP: EN.02: (Environmental 02)—Geographical circumstances restrict applicability of CE solutions Area: Environmental Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 4.00 Average urgency: 4.00 Frequency of specific CECP: 2 experts | Due to the geographical circumstances, the ability to implement certain circular economy procedures may be hampered. “The difference between geographical circumstances affects metabolic flows and applicability of solutions” [83] (p. 7). Articles: [83,101]. | Experts have mentioned that, indeed the geographical circumstances play an important role when implementing CE solutions. For example, in the case of islands, it is more complex due to their limited dimensions that impede economies of scale compared to other continental regions. No tourism specifications were highlighted by the experts. |

| Title of CECP: L.02: (Legal 02)—Legislation not adapted to efficiently regulate CE Area: Legal Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.36 Average urgency: 3.36 Frequency of specific CECP: 9 experts | Existing obstructing and inconsistent laws and regulations hamper circular practices. Service providers cannot legally retain ownership of a sold product, which makes it difficult to implement CE. Existing laws in waste management in some systems do not fit CE concepts. There is a lack of supporting government legislation with inadequately defined multi-level regulatory frameworks favoring linear processes. Legislation hinders circular business models, e.g., legislation on sales of waste materials and on cross-border movement of products for reuse. “Competition legislation inhibits collaboration between companies” [84] (p. 7). Articles: [6,11,15,74,79,80,82,84,85,86,91,93,97,98,107]. | According to the experts, existing regulations are interfering in the circular transformation of the tourism sector as the legal models are designed to favor the continuation of a linear economic model. For example, when it comes to the sharing of services/assets, i.e., hotel halls, hotel managers face legal barriers to do so. Another example is that certain regulations impede the reuse of materials as well as the end-of-life treatment of the waste to reincorporate appropriately into the supply chain. Furthermore, experts consider that there should be legal incentives to push citizens to choose the best environmental means of transportation, not only reflected in the price but through positive reward measures in place that induce more circular behaviors. For example, an application for the smartphone that can check in real-time the CO2 emissions of the user when deciding to use different means of transport in the region. If you stay below your monthly rate of CO2 emissions, you can convert the non-CO2 emissions in local currencies to purchase local food, etc. Negative COVID-19 effect: COVID-19 has implemented new regulations that strengthen the current linear models due to health and safety reasons. These are for example the compulsory use of single-use plastic items in the hospitality industry, F&B, which has put on hold the progress made toward reusable items. For example, in certain cafés, there is a trend to move away from reusable cups and back to the takeaway model. Even if clients are willing to use reusable cups the cafés will not accept them due to strict COVID-19 protocols in place dictated by the government. (Frequency: 9 experts mentioned this). |

| Title of CECP: L.03: (Legal 03)—Insufficient implementation of CE regulations Area: Legal Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.75 Average urgency: 3.25 Frequency of specific CECP: 4 experts | There is a lack of regulatory pressures. CE laws are not strong enough; there is no existing tool to analyze the effectiveness of the proposed rules and laws. Most laws are posed with personal opinion rather than technical expertise. There is an inadequate, complex, and fragmented legal system. “Governments and local authorities’ responsibilities are not clear on the implementation of CE” [73] (p. 9). Articles: [73,74,75]. | In order to move tourism businesses toward circularity, there needs to be a favorable institutional environment with regulative isomorphic pressures (i.e., laws, sanctions). Tourism companies need a clear indication of what they are allowed to do and what they are not allowed to do with regard to CE. If there are only normative isomorphic pressures, they will not do so, as they are just recommendations that are not legally binding. |

| Meta Data on CECPs | Explanation of CECP in the Literature | Specificities for the Tourism Industry |

|---|---|---|

| Title of CECP: R.01: (Resources 01)—Lack of experts on CE to hire and CE training offerings Area: Resources Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 4.00 Average urgency: 3.50 Frequency of specific CECP: 4 experts | There is not enough qualified workforce on CE. There is a lack of interest and understanding to apply CE across value chains. There is a need for training and education on CE. There is no official training available for employees in repair/refurbish and no guidelines for third-party repair companies. “Lack of qualified personnel in environmental management” [12] (p. 164). Articles: [12,73,91,94,95]. | The tourism industry lacks education in the circular economy as well. No tourism-specific aspect has been mentioned by the experts. Negative COVID-19 effect: The tourism industry has faced a serious economic crisis due to COVID-19. Experts argue that sustainability positions within organizations were the first ones to be cut. Furthermore, the unemployment rate in the industry has sharply increased. This has resulted in a CE brain drain toward other industries that were less impacted by COVID-19. (Frequency: 3 experts mentioned this). |

| Title of CECP: R.04: (Resources 04)—Lack of efficient market to source available and high-quality CE resources Area: Resources Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.67 Average urgency: 3.17 Frequency of specific CECP: 5 experts | There is limited availability and quality of recycling materials due to technological limitations for recycling, product design, and other processes. It is difficult to supply recycled/reused/refurbished products as there is limited demand for looped products. Lack of standardization on refurbishment products leads to a reduced quality. “Lack of market for recycled materials (e.g., glass, polymers)” [86] (p. 34) and “original spare parts are difficult or impossible to attain or have to be transported over long distances” [91] (p. 10). Articles: [15,74,79,80,84,86,91,95,106,107,108]. | The insufficiently developed supplier market for circular economic products as well plays an important role in the tourism industry. Especially, as the industry is characterized by a high scale demand of branded supplies. E.g., Hotels stated that they cannot purchase bamboo toothbrushes, as the provider are too small to provide the needed number for a hotel chain as well as they are not able to brand such a toothbrush, which is essential for a hotel chain. |

| Title of CECP: R.05: (Resources 05)—Lack of proof of solid CE theory, concepts, methods, measurements and role models (especially business models) Area: Resources Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.48 Average urgency: 3.17 Frequency of specific CECP: 21 experts | There is a lack of data and indicators to measure (long-term) benefits of CE activities. Lack of clear, reliable standards to assess CE processes, activities, and materials, leading to lack of public awareness and lack of demand for sustainable products. There is an absence of perceived need to move toward CE “many companies do not see how lifecycle thinking can be applied to their specific operations – or even the benefits of doing so. Many potential users are unaware of how life-cycle approaches can aid in decision making” (p. 20). There is limited awareness of successful CE business models in resource management and planning projects, as well as lack of successful business models to implement CE in supply chain. “Knowledge development in the field of circular business models is still in its infancy” [103] (p. 14). Articles: [11,15,74,75,79,80,84,86,89,91,92,96,99,100,101,103,106,107,109]. | For the tourism industry, the experts put a strong emphasis on collecting data about the circularity of the industry. Especially as the industry has the potential to be truly digital-enabled, allowing better communication. Some experts suggest, for example, that hotels should track the water consumption of tourists and communicate this to them. However, too many different measures exist within the tourism sector and standardization of circular economy measurement is needed. Experts emphasized that the industry needs to become more transparent about material flows with the help of data (how many materials come in, what materials come in, what materials remain, what materials become stock, what materials become buildings, what waste is generated), to circularize it. Another often cited challenge was having a specific international certification on CE for the tourism sector that is not seen as another “green certification” but as one with a solid international reputation that can be recognized and valued by all the stakeholders in tourism. |

| Title of CECP: VC.02: (Value Chain 02)—Complex and costly to adapt the value chain to reverse logistics Area: Value Chain Level of specificity: High Average importance: 4.00 Average urgency: 3.50 Frequency of specific CECP: 4 experts | The exchange of materials is limited by the capacity of reverse logistics. The reverse logistics organization and stability prevent companies from implementing circular business models. “The quality, access and attractiveness of recovered products and materials” [97] (p. 7) remains challenging. “Extending the supply chain to include remanufacturing, recycling, repair and refurbishing creates an additional level of complexity, leading to potentially negative impacts in quality, cost, and delivery times” [86] (p. 22). Articles: [11,84,86,97,104,106,107,108]. | Tourism practices make reverse logistics very difficult. It is cheaper for tourists to purchase many items at the destination than to bring them from their country of origin, to use them during their stay, and then throw them away. This makes it difficult for the tourism industry to establish reverse logistic models. If there would be a proper reverse logistics infrastructure in place, the goods would be collected, transported to a central location, and sorted for reuse, refurbish, or recycling purposes. So, the challenge is two-fold: it requires the involvement of the tourists to return end-of-use products and it requires businesses to look at their wider business model to make sure that products and materials can be reused, remanufactured, repaired, or recycled. |

| Title of CECP: VC.03: (Value Chain 03)—Lack of willingness and trust to collaborate across the value chain Area: Value Chain Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.67 Average urgency: 3.67 Frequency of specific CECP: 13 experts | Network collaboration across the value chain (VC) to facilitate the implementation of CE all along remains very complex. It is very difficult to find and create the appropriate, trustworthy networks (especially from the supply chain) necessary for circularity. “From a supply perspective, a major challenge seems to be the absence of ‘green’ suppliers for specific inputs that the SME needs in the production process of a product or a service. According to the SMEs, in most cases, markets for these inputs are absent or insufficiently developed in the supply chain. Also, some SMEs report difficulties in implementing a green solution since they are locked in at the bottom of the supply chain or they are part of global supply chains sectors with correlated high environmental impact” [87] (p. 10). It is complicated to have a strong commitment toward the implementation of CE and to get the entire industry on board, as not all, e.g., packaging component manufacturers, packaging equipment users, material producers, waste recovery facilities, have the same interests. “Involves actors from across society and creation of suitable collaboration and exchange patterns” [106](p. 1033) and “CBM is based on collaboration, and that requires trust between parties” [107] (p. 5). Articles: [11,15,74,80,86,87,91,93,101,103,106,107,110,111]. | For the tourism industry, this is clearly the case, as there is a great number of agents across the tourism value chain, which is very extensive and fragmented. Many experts have insisted on the complexity of applying systems thinking in the tourism industry due to the many stakeholders involved. Furthermore, the highly fragmented and extensive tourism industry makes it even more difficult to achieve a coordinated vision to circulate the sector as there is barely any cross-sectoral collaboration. For instance, it is possible to find solutions for the circularity of food, circularity of plastics, but not necessarily within the entire sector. To tackle this missing collaboration and coordination across the tourism value chain, experts have proposed that “transition brokers” are needed to make the transition effect when moving toward CE. |

| Title of CECP: I.02: (Infrastructure 02)—Inefficient waste management/recycling systems, practices and infrastructures Area: Infrastructure Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.90 Average urgency: 3.70 Frequency of specific CECP: 8 experts | Lack of economies of scale in waste treatment/recycling hinders the implementation of appropriate infrastructure necessary for CE, as “it is prohibitively costly for individual organizations to invest in smart enabling technologies for waste management” [75](p. 19). Furthermore, some regions cannot reach economies of scale, as there is not enough amount of waste and also due to the geographic conditions, such as islands with certain conditions that limit their possibilities as isolated environments, “the bulk density of the roasted material makes it difficult to transport and store it from an economic point of view” [90] (p. 4). Not all regions have the necessary waste containers in public spaces for appropriate waste separation and “points for separated waste collection frequently becoming wasted areas (illegally dumped litter near the separate collection bins)” [79](p. 8). Non-integrated poor waste infrastructure and long distances between waste generation and treatment. “Dual waste system (households/ industrial) hinders waste management optimization” [79](p. 7). Many of the areas performing landfilling and incineration activities lack adequate technologies. It is difficult to clearly allocate responsibilities on waste management. Articles: [73,75,79,80,81,85,90,92,93,95,96,98,101]. | Inefficient waste management infrastructures are as well highly relevant for the tourism industry but are not specific in any way to the industry. Gray and black water recycling are also highly relevant for the tourism industry in order to improve the water circularity across the hospitality sector, however the costs are very high compared to the costs of not doing so, making the adoption of this practice unattractive. Negative COVID-19 effect: More waste has been generated due to the new health and safety measures in place (such as gloves, PPE (personal protective equipment), disposable face masks) and its improper waste management putting more pressure on the environment. For example, one expert mentioned that in certain developing countries that are highly dependent on tourism, the waste infrastructures were not working as they are privately owned and function only with the income generated by the tourism industry. (Frequency: 3 experts mentioned this COVID-19 effect). |

| Title of CECP: I.03: (Infrastructure 03)—Difficult to implement CE spatial planning and transportation infrastructure Area: Infrastructure Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.50 Average urgency: 3.33 Frequency of specific CECP: 6 experts | Lack of spatial planning mechanisms following CE rules and difficulties in managing complex urban systems. “Tension between urban planning and facilitating the kind of experimentation that CE calls for (how to manage the changing economy and the changing structure in a built form)” [81] (p. 2200). The socio-technical lock-in hinders the implementation of CE, “even if there is willingness amongst institutions providing urban infrastructure and services to adopt circular design or integrated approaches, it is practically difficult to alter these infrastructural systems due to the capital cost and disruption generated by such a radical transformation” [80](p. 10). Articles: [80,81,101]. | Space has been planned without CE in mind, and infrastructures have already been established. Changing this for CE purposes represents an important disruption of the established systems. In addition, important to the tourism industry, but without any tourism specificities. |

| Meta Data on CECPs | Explanation of CECP in the Literature | Specificities for the Tourism Industry |

|---|---|---|

| Title of CECP: STRAT.01: (Strategy 01)—Shareholder interests not aligned with CE, lack of CE vision Area: Strategy Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.75 Average urgency: 3.33 Frequency of specific CECP: 9 experts | Dealing with a trade-off on whether to have short-term profitability or long-term sustainability. As CE usually involves high short-term costs and low short-term economic benefits instead of low short-term costs and high short-term benefits from a linear economy. “Focus on short-term returns on investment” and “missing the strategic relevance of sustainable development” [106] (p. 1033). CE approaches are not always seen as profitable (e.g., high requirements for pollution reduction and energy saving) and insufficient ROI, which makes it harder to attract investment. This lack of investment power challenges the implementation of CE. In addition, there is a lack of holistic thinking and a multi-stakeholder approach. There is a high focus on individual company interests and a lack of CE vision. Businesses face important amounts of sunk value and sunk cost that have already been invested in suppliers, real capital, and human capital making it very difficult to transform their approach toward CE. Articles: [74,75,80,82,84,85,86,88,89,93,94,95,96,100,101,106,108,112]. | The key players in moving the tourism industry toward CE are hotels. The hotel business is characterized by two main shareholder groups: the owner of the hotels and the shareholders of the brands that operate the hotels. Both shareholders are short-term oriented, for different reasons. Many shareholders are short-term oriented as they seek to optimize their share prize in the short term. Hotel owners on the other side, only have 1–3-year contracts with hotel brands. Thus, they have a great focus to perform well in this time to hopefully renew the contract. Short-term orientation of those two key shareholder groups represents a crucial challenge for moving toward a circular economy in the tourism industry. In addition, experts have mentioned that older generations of hotel owners see the less the need of being sustainable compared to the new generations of hotel owners. Negative COVID-19 effect: Businesses have changed their priorities with regards to sustainability. They are focusing on survival rather than on making big investments to become a more circular business as they are lacking the financial resources to make the green and digital shift needed to achieve circularity, renovate their buildings, change their portfolio, find other more sustainable suppliers, etc. Moreover, they are also facing a lot of pressure to go back to the status quo in order to maintain the ROI. (Frequency: 14 experts have mentioned this). |

| Title of CECP: STRAT.02: (Strategy 02)—Lack of transparency, forecast ability and difficult decision making Area: Strategy Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.33 Average urgency: 3.33 Frequency of specific CECP: 3 experts | There is a lack of end-to-end visibility and forecast ability hindering the implementation of CE. The challenge of validation not being achievable until further sales make CE adoption riskier. Both poor forecast ability and difficult validation make decision making more challenging to implement CE in the most efficient and effective way. Businesses are not certain that demand or input prices will not go back to past levels and there is uncertain return. “The business cannot be sure what new technologies and business environments will emerge such that if it tries to change too fast now, it will miss a better investment opportunity in the future” [112] (p. 19). Articles: [6,74,107,108,110,112]. | Tourism businesses lack the needed KPIs to measure their circularity. |

| Title of CECP: STR.01: (Structure 01)—Missing organizational abilities and structure for CE Area: Structure Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.33 Average urgency: 3.33 Frequency of specific CECP: 3 experts | Depending on how the organization is structured, it will enable or hinder the implementation of CE in their business model. Lack of organizational capabilities that are necessary to implement circular practices across the organization’s several functions. “Often, life-cycle practitioners are functionally a part of a company’s environment, safety, and health division – separated or disconnected from the process design and product development departments. Thus, the knowledge of the life-cycle practitioners is not shared with developers, and the developers may not be aware of how life-cycle thinking can be integrated into design and development” [109] (p. 20). Articles: [74,93,109]. | The structure of the hotel business in the tourism industry is a key reason why shareholder interests are not aligned with CE initiatives. Managers of hotels are rarely the owners of the hotel (franchise contract); they are rather HR managers. Thus, they do not have the decision power to change the physical setting in which they operate. Furthermore, hotel chains have many levels of hierarchy, making it difficult to get changes approved. If a hotel manager wants to change something, even if it is a small action, he first needs to ask permission from the head office of the chain, and they will evaluate if the decision could have negative effects on the hotel chain’s profitability. This slows down the whole decision-making process to take certain circular actions that could benefit the business. |

| Title of CECP: CULT.01: (Culture 01)—Lack of managerial commitment and leadership towards CE Area: Culture Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 4.00 Average urgency: 3.80 Frequency of specific CECP: 5 experts | From the top down, managerial commitment and weak leadership toward CE are major challenges, which are argued by time constraints and reliance on business leaders to make the CE transition. From the bottom up, heavy organizational hierarchies prevent bottom-up experimenting. “Lack of leadership commitment” [75] (p. 20). Articles: [11,74,75,79,85,87,91,98,106,109,112]. | Lack of managerial commitment is a key issue in the tourism industry. However, the experts did not mention any specific aspect related to tourism. |

| Title of CECP: CULT.02: (Culture 02)—Resistance to changes towards CE and conflict with the existing culture Area: Culture Level of specificity: High Average importance: 2.71 Average urgency: 3.14 Frequency of specific CECP: 5 experts | Not all organizations are willing to change their business models to make them more or fully circular due to internal resistance to risk among managers and shareholders, rigidity in business routines, and different preferences (preferences for incremental over radical innovation). The aversion to risk is a common resistance challenge toward the adoption of CE due to costly implementations. The hesitant company culture with a predominant linear mindset encourages resistance to change toward CE. The prevailing structures in many industries, known as “linear lock-in”, act as a barrier to the implementation of CE. “Conflict of interest within companies” [93] (p. 2). The already settled company culture conflicts with CE adoption due to again risk aversion, and the poor internal cooperation is difficult too. The silo thinking in the business’s culture reduces the organization’s efficiency. Articles: [6,11,15,80,82,85,87,91,93,97,100,105,106,107,110]. | The resistance toward change in tourism is deeply rooted in the culture of tourism companies to do everything possible to serve the customer. The direct feedback loops of platforms such as TripAdvisor enforces a culture that fears change. Tourism companies rather have a customer-centric reactive culture than an innovative, proactive one based on their own drivers. |

| Title of CECP: CUSTS.01: (Customer Segment 01)—Only niche markets for CE offerings Area: Customer Segment Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 2.00 Average urgency: 2.50 Frequency of specific CECP: 2 experts | The majority of customers are not willing to pay higher prices for CE offerings due to three reasons: Segment A is highly price-sensitive with no specific interest in sustainable offerings; Segment B is price-insensitive, caring about the environment but not aware of the impact of their purchase decisions; and Segment C is price-insensitive and aware of its purchase impact but lacks knowledge regarding the environmental impact of different offerings. “Used products are often considered more or less inferior, an idea that is strongly supported by marketing of new products. This preference limits the potential of organizing local collection and exchange of goods” [75](p. 13) Articles: [12,20,74,75,79,84,87,91,96,97,100,103,104,106,107,110]. | Experts agree that the market demanding circular offerings is also small in the tourism industry, but they do not mention any specificity for the tourism industry. |

| Title of CECP: CUSTS.02: (Customer Segment 02)—Low willingness to pay for CE offerings Area: Customer Segment Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.00 Average urgency: 2.60 Frequency of specific CECP: 5 experts | Consumers are not always willing to pay a plus for environmentally friendly products as price is a very decisive factor when tacking the final purchase decision. Circular products may be characterized by high selling prices due to enhanced quality (durability) or upgradability, thus constituting a barrier for the customer. It is important to increase the visibility of the benefits of the products to be able to argue for higher prices. “From a demand perspective, a major challenge underlined by the majority of SMEs is the need to create a business case for customers in order to buy a green product or to use a green service[…]the need to provide accurate figures and additional evidence of benefits related to green goods and services, the need to convince potential customers that the circular economy approach is the way forward, and the misperception of customers that green products and services are of lower quality than traditional goods and services” [87] (p. 10). Articles: [12,20,79,87,100]. | Experts agree that tourists have a low willingness to pay for CE offerings. One approach would be to lower prices for CE offerings. For instance, experts pointed out that a few nights at a hotel are often more expensive than a monthly rent at home; therefore, tourists expect to have outstanding experiences and are not willing to make compromises to have more CE offerings. |

| Title of CECP: CUSTR.01: (Customer Relationships 01)—Difficulty in efficiently branding CE offerings and low status of looped offerings Area: Customer Relationships Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.83 Average urgency: 3.67 Frequency of specific CECP: 5 experts | CE looped products are not perceived as equally good as new products. In addition, inadequate branding of looped offerings affects the purchasing behavior of consumers. “Low status of products from recycled materials and repaired, reused, refurbished or remanufactured products” [91] (p. 10). Articles: [86,91,100,104,108]. | As the tourism industry relies rather on selling services than products, experts have not mentioned any challenges regarding the perceived status of the quality of the offering. Experts, however, agreed that communicating about CE offerings represents a challenge, as, on the one side, CE is not necessarily a concept that tourists are aware of (is perceived as a confusing buzzword), and on the other side, there is the risk that tourist believes the company is rather interested in greenwashing practices rather than in having a truly circular ambition. |

| Title of CECP: VP.01: (Value Proposition 01)—Challenging to create efficient CE value proposition designs for complex offerings Area: Value Proposition Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.57 Average urgency: 3.29 Frequency of specific CECP: 5 experts | There is limited focus on achieving circularity when it comes to product design. There are many design challenges to durable reuse and recovery products. The product complexity also hinders Life-Cycle Assessments. There is a lack of sufficient guidelines toward product design that enable circularity. “The difficulties related to the use of tools available to support the design of sustainable PSSs (product service systems)” [110] (p. 4) is also a challenge to implement CE. Articles: [15,74,84,86,88,91,99,108,110,111]. | Experts have mentioned that businesses in the tourism sector focus too much on downstream solutions instead of on upstream innovations and on implementing other business models such as “product as a service”. |

| Title of CECP: VP.02: (Value Proposition 02)—CE offerings often inferior to linear economy offerings Area: Value Proposition Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.00 Average urgency: 3.00 Frequency of specific CECP: 2 experts | The CE offerings are perceived to have inferior quality, performance, worse customer demand fit, etc. When it comes to redesigning circular products, it is difficult to maintain the same quality level as before. “Worse performance of the services” [102] (p. 924). Articles: [93,99,102]. | It is difficult to maintain a balance between quality, quantity, and sustainability in the tourism sector, which is very dependent on maximizing customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. For instance, it is difficult to provide the quality expected at a food buffet of a hotel chain where customers demand a wide variety of options without generating enormous amounts of food waste. |

| Title of CECP: KP.01: (Key Partners 01)—Difficulties in finding suitable CE partners and building solid relationships with them Area: Key Partners Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 4.00 Average urgency: 3.00 Frequency of specific CECP: 2 experts | A multi-stakeholder approach is necessary to facilitate the circularity throughout the whole value chain, which has been proven to be very complex when it comes to dealing with the appropriate partners that follow CE principles. Businesses lack the support and long-term cooperation from their key partners. “Companies who decide to move towards CE often experience difficulty in finding appropriate supply chain partners, with appropriate skills and a CE approach” [100] (p. 7404). Articles: [73,79,86,93,100,106,111,112]. | Experts mention that tourism companies seeking to be circular have difficulties finding circular economic suppliers. This is a challenge that is not specific to the tourism industry. |

| Title of CECP: KR.01: (Key Resources 01)—Lack of CE related technical resources and know-how Area: Key Resources Level of specificity: High Average importance: 3.62 Average urgency: 3.38 Frequency of specific CECP: 6 experts | Companies lack adequate technologies to be able to adopt innovative CE practices. “Need for technical and technological know-how and expertise” [93] (p. 2). Articles: [6,11,12,91,93,94,96,97,98]. | The discussion around technical resources and know-how in the tourism industry is very much focused on the topic of waste management. Especially the management of food waste from hotels and restaurants plays a prominent role. The key challenge is that tourism companies lack the technologies and know-how to track this waste. Even if some tourism companies invest in waste management technologies, they lack the transparency needed to tell if those technologies have a significant impact. The result is an inefficient use of waste management technologies and low adoption of such technologies in tourism. Furthermore, best practices are not shared among tourism players, keeping the know-how in siloes instead of sharing it. |

| Title of CECP: KR.03: (Key Resources 03)—Lack of CE skilled Human Resources within the company Area: Key Resources Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 3.67 Average urgency: 3.83 Frequency of specific CECP: 6 experts | Lack of professionals with the necessary skills in CE practices can help the company change its current linear business model toward a circular business model. “Skills shortage to manage the radical innovations needed to transition towards a sustainable, circular economy, for which knowledge often needs to be sourced from outside the organization” [106] (p. 1033). Articles: [87,91,96,99,106]. | No tourism specificity is mentioned by experts. As in other industries, the tourism industry lacks employees trained in a circular economy. |

| Title of CECP: RS.01: (Revenue Streams 01)—Cannibalization of sales due to new circular products Area: Revenue Streams Level of specificity: Low Average importance: 1.00 Average urgency: 1.00 Frequency of specific CECP: 2 experts | There is a risk of cannibalization due to new circular products diverting sales from existing ones, which can affect the revenue streams obtained from “linear” traditional products, thus reducing the whole future sales of the business. “Risk of cannibalization similar to fashion vulnerability hinders production of long-lasting high-quality products” [107] (p. 5). Articles: [91,98,104,107,108]. | Cannibalization of traditional offerings by circular offerings is also in the tourism industry seen as a challenge. Most importantly, this challenge is seen for travel agencies, who might not be willing to offer circular packages next to their traditional ones. |

| Title of CECP: CS.03: (Cost Structure 03)—Very high upfront investment costs to implement CE Area: Cost Structure Level of specificity: High Average importance: 2.83 Average urgency: 2.50 Frequency of specific CECP: 6 experts | Very high upfront investment costs hinder the implementation of CE practices, especially in the supply chain. This high upfront investment does not pay back instantly, which blocks investment on CE practices prioritizing investment on linear economy approaches as they usually have short-term economic returns. “High upfront investment costs make ‘circular’ products more expensive” [88] (p. 4). Recycled materials are generally more expensive in CBM than in linear business models, as acquiring different looped resources and qualified personnel can be more expensive. Furthermore, the lack of capital access to face the high upfront investment costs creates lock-in effect, thus impeding businesses to engage with CE. Articles: [6,15,73,74,82,84,88,93,96,97,98,99,103,105,107,108]. | Regarding upfront investments to move toward a circular economy, the tourism industry acknowledges high upfront investments to change assets (such as lower water consumption or higher energy efficiency of hotel buildings). However, experts argue that being a service-oriented industry much can be done by simply changing practices of people working in the tourism industry, which in comparison with asset-heavy product-focused industries require far fewer upfront investments. Especially as a key for moving toward circular economy in tourism seems to be the creation and management of food waste. Experts argue that more circular practices in this field could be simply implemented by training the staff. |

References

- United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA; London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; Ioannou, A. The Circular Economy: Barriers and Opportunities for SMEs. CEPS Work. Doc. 2015. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2664489 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Preston, F.A. Global redesign? Shaping the circular economy. Energy Environ. Resour. Gov. 2012, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazi, S.; Wiktorsson, M.; Kurdve, M.; Jönsson, C.; Bjelkemyr, M. Material Efficiency in Manufacturing: Swedish Evidence on Potential, Barriers and Strategies. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 127, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, A.; Mendonça, S. Lost in transition? Drivers and Barriers in the Eco-Innovation Road to the Circular Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranta, V.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Ritala, P.; Mäkinen, S.J. Exploring institutional drivers and barriers of the circular economy: A cross-regional comparison of China, the US, and Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, O.; Plepys, A.; Whalen, K.; Nußholz, J.L.K. Business Model Innovation for a Circular Economy: Drivers and Barriers for the Swedish Industry–the Voice of REES Companies; Report from the International Istitute for Industrial Environmental Economics; Lund University: Lund, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Doberstein, B. Developing the circular economy in China: Challenges and opportunities for achieving ‘leapfrog development’. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2008, 15, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geng, Y.; Haight, M.; Zhu, Q. Empirical analysis of eco-industrial development in China. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, N.; Hanski, J.; Ahola, T.; Ståhle, M.; Piiparinen, S.; Valkokari, P. Unlocking circular business: A framework of barriers and drivers. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 212, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, M.; Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Puga-Leal, R.; Jaca, C. Circular economy in Spanish SMEs: Challenges and opportunities. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 185, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cabrera, J.; López-del-Pino, F. The circular economy challenges and its paradigm shift in the tourism industry: Lessons from a mature touristic destination. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Development ICSD 2020, New York, NY, USA, 21–22 September 2020; Available online: https://ic-sd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Julia-Cabrera.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Alexander, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Silverstein, M.; Jacobson, M.; Fiksdahl-King, I.; Schlomo, A. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the circular economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC). Annual Economic Impact Report. Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Van Rheede, A. Circular Economy as an Accelerator for Sustainable Experiences in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/17064315/Circular_Economy_as_an_Accelerator_for_Sustainable_Experiences_in_the_Hospitality_and_Tourism_Industry (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, L.F.; Nocca, F. From linear to circular tourism. Aestimum 2017, 70, 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, F.; Bærenholdt, J.O. Tourist practices in the circular economy. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, C. Exploring circularity: A review to assess the opportunities and challenges to close loop in Nepali tourism industry. J. Tour. Adventure 2020, 3, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, D. Sustainable urban infrastructure in China: Towards a factor 10 improvement in resource productivity through integrated infrastructure systems. Int. J. Sust. Dev. World 2008, 15, 288–301. [Google Scholar]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The circular economy–a new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kirchherr, J.; van Santen, R. Research on the circular economy: A critique of the field. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulding, K. The economics of the coming spaceship earth. In Environmental Quality in a Growing Economy: Essays from the Sixth RFF Forum; Jarrett, H., Ed.; Johns Hopkins University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1966; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment; Johns Hopkins University Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, M.S. An introductory note on the environmental economics of the circular economy. Sustain. Sci. 2007, 2, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Heshmati, A.; Geng, Y.; Yu, X. A review of the circular economy in China: Moving from rhetoric to implementation. J. Clean Prod. 2013, 42, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariatli, F. Linear economy versus circular economy: A comparative and analyzer study for optimization of economy for sustainability. Visegr. J. Bioecon. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 6, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benyus, J.M. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature; William Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hawken, P.; Lovins, A.B.; Lovins, L.H. Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution; Routledge: Boston, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Cradle to Cradle in a Circular Economy-Products and Systems. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/schools-of-thought/cradle2cradle (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schut, E.; Crielaard, M.; Mesman, M. Circular Economy in the Dutch Construction Sector: A Perspective for the Market and Government. RIVM Report 2016-0024. 2016. Available online: https://rivm.openrepository.com/handle/10029/595297 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications/towards-a-circular-economy-business-rationale-for-an-accelerated-transition (accessed on 25 February 2021).

- Manniche, J.; Topsø Larsen, K.; Brandt Broegaard, R.; Holland, E. Destination: A Circular Tourism Cconomy: A Handbook for Transitioning toward a Circular Economy within the Tourism and Hospitality Sectors in the South Baltic Region; Centre for Regional & Tourism Research (CRT): Bornholm, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Sánchez, A. The unavoidable disruption of the circular economy in tourism. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2018, 10, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.; Florido, C.; Jacob, M. Circular economy contributions to the tourism sector: A critical literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido, C.; Jacob, M.; Payeras, M. How to carry out the transition towards a more circular tourist activity in the hotel sector. The role of innovation. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, P.; Wynn, M.G. The circular economy, natural capital and resilience in tourism and hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. M. 2019, 31, 2544–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; Alonso-Almeida, M.d.M. The circular economy strategy in hospitality: A multicase approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paré, G.; Tate, M.; Johnstone, D.; Kitsiou, S. Contextualizing the twin concepts of systematicity and transparency in information systems literature reviews. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerth, N.L.; Cunningham, W. Using patterns to improve our architectural vision. IEEE Softw. 1997, 14, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altshuller, G.S. The Innovation Algorithm: TRIZ, SystematicIinnovation and Technical Creativity; Technical Innovation Center, Inc.: Worcester, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Salustri, F.A. Using design patterns to promote multidisciplinary design. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Multi-disciplinary Design Engineering CSME, Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–22 November 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann, O.; Frankenberger, K.; Csik, M. The Business Model Navigator: 55 Models That Will Revolutionise Your Business; Pearson Education Ltd.: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Amshoff, B.; Dülme, C.; Echterfeld, J.; Gausemeier, J. Business model patterns for disruptive technologies. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2015, 19, 1540002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weill, P.; Vitale, M. Place to Space: Migrating to Ebusiness Models; Harvard Business Press: Boston, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelkafi, N.; Makhotin, S.; Posselt, T. Business model innovations for electric mobility—What can be learned from existing business model patterns? Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 17, 1340003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.; Scholes, K.; Whittington, R. Exploring Corporate Strategy: Text & Cases; Pearson Education: Essex, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kralj, D. Sustainable Green Business. Advances in Marketing, Management and Finances, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Management, Marketing and Finances, Houston, TX, USA, 30 April–2 May 2009. p. 30. Available online: http://www.wseas.us/e-library/conferences/2009/houston/AMMF/AMMF22.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Rüegg-Stürm, J. The New st. Gallen Management Model: Basic Categories of an Approach to Integrated Management; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, M.N. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam. Pract. 1996, 13, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieder, M.; Rashid, A. Towards circular economy implementation: A comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 115, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; De Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; Van Der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bouwmeester, O.; Stiekema, J. The paradoxical image of consultant expertise: A rhetorical deconstruction. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 2433–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. The role of the consultant: Content expert or process facilitator? Pers. Guid. J. 1978, 56, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Charles, K. Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Handcock, M.S.; Gile, K.J. Comment: On the concept of snowball sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 2011, 41, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Robertson, C.; Glidewell, L.; Entwistle, V.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.M. The significance of saturation. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruschka, D.J.; Schwartz, D.; St. John, D.C.; Picone-Decaro, E.; Jenkins, R.A.; Carey, J.W. Reliability in coding open-ended data: Lessons learned from HIV behavioral research. Field Methods 2004, 16, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olswang, L.B.; Svensson, L.; Coggins, T.E.; Beilinson, J.S.; Donaldson, A.L. Reliability issues and solutions for coding social communication performance in classroom settings. J. Speech Lang. Hear Res. 2006, 49, 1058–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remane, G.; Hildebrandt, B.; Hanelt, A.; Kolbe, L.M. Discovering new digital business model types-a study of technology startups from the mobility sector. In Proceedings of the Pacific-Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS, 2016), Chiayi, Taiwan, 27 June–1 July 2016; p. 289. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Sezersan, I.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Gonzalez, E.D.R.S.; Moh’d Anwer, L.S. Circular economy in the manufacturing sector: Benefits, opportunities and barriers. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1067–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Govindan, K.; Hasanagic, M. A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: A supply chain perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 278–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Venkatesh, V.G.; Liu, Y.; Wan, M.; Qu, T.; Huisingh, D. Barriers to smart waste management for a circular economy in china. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 240, 118198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Circular Economy Systems Diagram. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy/concept/infographic (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Universal Circular Economy Policy Goals. Enabling the Transition to Scale. Available online: https://policy.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/universal-policy-goals (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obersteg, A.; Arlati, A.; Acke, A.; Berruti, G.; Czapiewski, K.; Dabrowski, M.; Heurkens, E.; Mezei, C.; Palestino, M.F.; Varjú, V. Urban regions shifting to circular economy: Understanding challenges for new ways of governance. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, J. Circular cities: Challenges to implementing looping actions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bolger, K.; Doyon, A. Circular cities: Exploring local government strategies to facilitate a circular economy. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 2184–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.; Gianoli, A.; Grafakos, S. Getting the ball rolling: An exploration of the drivers and barriers towards the implementation of bottom-up circular economy initiatives in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. J. Environ. Plann. Man. 2020, 63, 1903–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varjú, V.; Dabrowski, M.; Amenta, L. Transferring circular economy solutions across differentiated territories: Understanding and overcoming the barriers for knowlege transfer. Urban Plan. 2009, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Masi, D.; Kumar, V.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Godsell, J. Towards a more circular economy: Exploring the awareness, practices, and barriers from a focal firm perspective. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cother, G. Developing the circular economy in tasmania. Action Learn. Res. Pract. 2020, 17, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veleva, V.; Bodkin, G. Corporate-entrepreneur collaborations to advance a circular economy. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 188, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; Van der Gaast, W.; Hofman, E.; Ioannou, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Flamos, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Papadelis, S.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M. Implementation of circular economy business models by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and enablers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell-Johnston, K.; ten Cate, J.; Elfering-Petrovic, M.; Gupta, J. City level circular transitions: Barriers and limits in Amsterdam, Utrecht and The Hague. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 235, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, M.; Longo, M.; Zanni, S. Circular economy in Italian SMEs: A multi-method study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uche-Soria, M.; Rodríguez-Monroy, C. An efficient waste-to-energy model in isolated environments. Case study: La Gomera (Canary Islands). Sustainability 2019, 11, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guldmann, E.; Huulgaard, R.D. Barriers to circular business model innovation: A multiple-case study. J. Clean Prod. 2020, 243, 118160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, N.; Mayers, K.; Van Wassenhove, L.N. Stakeholder views on extended producer responsibility and the circular economy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, A.; Rossi, J.; Pellegrini, M. Overcoming the main barriers of circular economy implementation through a new visualization tool for circular business models. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ormazabal, M.; Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Jaca, C.; Santos, J. An overview of the circular economy among SMEs in the Basque Country: A multiple case study. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. (JIEM) 2016, 9, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scarpellini, S.; Portillo-Tarragona, P.; Aranda-Usón, A.; Llena-Macarulla, F. Definition and measurement of the circular economy’s regional impact. J. Environ. Plann. Man. 2019, 62, 2211–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Geng, Y.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.H. Barriers to promoting eco-industrial parks development in China: Perspectives from senior officials at national industrial parks. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Bocken, N.; Balkenende, R. Why do companies pursue collaborative circular oriented innovation? Sustainability 2019, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pietzsch, N.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; de Medeiros, J.F. Benefits, challenges and critical factors of success for zero waste: A systematic literature review. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 324–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reim, W.; Parida, V.; Sjödin, D.R. Circular business models for the bio-economy: A review and new directions for future research. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bressanelli, G.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Challenges in supply chain redesign for the circular economy: A literature review and a multiple case study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7395–7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nowakowska, A.; Grodzicka-Kowalczyk, M. Circular economy approach in revitalization: An opportunity for effective urban regeneration. Ekon. Sr. 2019, 4, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, P.; Giacosa, E. Cognitive biases of consumers as barriers in transition towards circular economy. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buren, N.; Demmers, M.; Van der Heijden, R.; Witlox, F. Towards a circular economy: The role of Dutch logistics industries and governments. Sustainability 2016, 8, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hopkinson, P.; Zils, M.; Hawkins, P.; Roper, S. Managing a complex global circular economy business model: Opportunities and challenges. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mattos, C.A.; De Albuquerque, T.L.M. Enabling factors and strategies for the transition toward a circular economy (CE). Sustainability 2018, 10, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velenturf, A.P.M.; Jopson, J.S. Making the business case for resource recovery. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oghazi, P.; Mostaghel, R. Circular business model challenges and lessons learned—An industrial perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Werning, J.P.; Spinler, S. Transition to circular economy on firm level: Barrier identification and prioritization along the value chain. J. Clean Prod. 2020, 245, 118609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, J. Life cycle approach-based methods-overview, applications and implementation barriers. Zesz. Nauk. Organ. Zarządzanie/Politech. Śląska 2019, 136, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R.J. Sustainable product-service systems and circular economies. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]