2. Literature Review

The report of the World Commission on Development and Environment (WCED), defined sustainable development as, “Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generation to meet their own needs” [

5]. Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) emphasize the need for development and environmental safeguard while seeking economic growth and profit [

6]. Sustainability is now a topic of concern in every sector and the tourism sector is also one of them [

7]. The tourism sector mainly comprises the buyers of services and products (tourists) and the intermediaries who make the services and products (tour operators and others) available to the tourists [

8]. Tour operators being the main player in the sector providing tour packages and services are the major focus of this study. The primary role of tour operators in stimulating sustainable tourism is very important [

9]. The Tour Operators Initiative (TOI), has especially been designed for tour operators around the globe. TOI was developed by the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP); the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); and the UNWTO already in 2000 [

10,

11]. This inventiveness has a global scope and reassures tour operators to incorporate environmental, cultural, and societal deliberations in the design of tourism suites and their operations [

11,

12].

Some researchers, such as Mannings (1992), have outlined the role of legislation, policy, and regulation in sustainable tourism but have no reference to the intermediaries such as the tour operators or travel agents [

13]. Tour operators have a substantial impact on the way tourism has developed in the past thirty years in many destinations [

2]. Being intermediaries in the supply chain several authors have highlighted the interest of tour operators in promoting environmental management (green management) in tourist destinations [

14]. Several studies show that tour operators can play a significant role in employing sustainable practices in the tourism sector as mentioned by [

11]. In the tourism sector, tour operators provide a critical link between supply and demand. They join hands with several organizations and provide a package to tourists at a single price [

12]. Given the importance of the role of tour operators in promoting sustainable tourism, the Tour Operators Initiative (TOI) has been launched in 2000 by United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP); United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); and the UN World Trade Organization (UNWTO) [

7].

Tourism is considered to be one of the driving forces for economic development [

15]. Tourism boosts foreign exchange and generating employment opportunities, the benefits of tourism cannot be negated as the literature proves that an increase in tourism activities leads to increased economic activity [

16]. There is a positive impact of tourism on employment [

17]. Using annual time series data from 1971–2008 from Pakistan, Adnan Hye and Ali Khan [

18] concluded that there is a long-term correlation between tourism income and the economic development of Pakistan. Tourism has also been noticed to have negative impacts on the environment if not managed sustainably. Lenzen et al. [

19] have stated that the tourism industry also contributes to the Green House Gases (GHG) emissions by 8%. The study further predicts the emissions to reach 12% which is detrimental to the environment and ultimately will add to global warming.

According to various researchers [

20,

21,

22] sustainable tourism focuses on socioeconomic and environmental improvement that aims at the enhancement of tourist experiences. According to Buckley [

23] the term ‘sustainable tourism’ was used two decades ago for the first time. During the first ten years, basic frameworks were studies from backgrounds in tourism, economics, and environmental management. After that, the second decade produced several conceptualizations and critiques including Liu [

24], Lane [

25], Sharpley [

20], and Bramwell and Lane [

26]. There are several definitions of sustainable tourism. However, the one mostly used in literature is the famous definition, which states that sustainable development is a development that fulfills the needs of the present minus compromising the capability of future generations to meet their own needs. The World Tourism Organization (WTO) defines sustainable tourism as something that meets the needs of present tourists and host regions while at the same time protecting and enhancing opportunities in the future. The resources are managed in such a way that the social, economic, and environmental aspects are taken care of [

27]. The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) Criterion has been created to provide a common understanding of the concept of ‘sustainable tourism’ and are a set of least criterion that are endorsed to be met by those aspiring to develop sustainable tourism activities [

28].

The industry of tourism encompasses a varied range of different sub-sectors and services and every player wants to pursue their business interests or profit maximization goals. Among these players are the tourism enterprises such as hotels, tour operators, restaurants, destination management organizations (private, public, and both), and local residents or communities. These different kinds of interests can often be conflicting [

29]. Every entity wants to have its own greater market share. It is believed that everybody wishes for extra business and a larger market portion [

30]. According to Carey et al., tour operators are not very interested in the development for decades to come (long term) [

2]. The focus merely on the short-term and seasonal gains. This leads to unsustainable tourism. While sustainable tourism focuses on longer-term impacts on the environment, society, and culture. The tour operators control the whole tourism experience from marketing to providing all services. Tour operators do not have any ownership or sense of responsibility towards the destinations and they only choose on what market segments to focus on. This leads to a situation where the tour operator usually focuses on a destination and moves to another destination after reaping all the benefits or financial gains [

31]. Sustainable tourism, however, depends upon the operators as well as the destination or local community. A varying degree of involvement from both sides is necessary to ensure sustainable tourism [

32].

Harrison et al. has mentioned practical encounters of sustainable tourism development in developing countries such as the Caribbean [

33]. The study suggests that for sustainable tourism more integrated planning was needed between tourism practitioners, academics, and government officials. Secondly, the vision is necessary at a high government level to decide what kind of tourists the country plans to attract. Some responsible tourists would like to avail the services of the tour operators. Kennett-Hensel et al. assessed the feedback they received from the managers of tour companies in Jamaica to develop the country’s master plan for tourism development and this master plan focused on conserving biodiversity and promoting cultural heritage [

34]. The master plan also discusses the Global Sustainable Tourism Criterion.

Nicholas and Thapa [

35] have analyzed the tourists’ perceptions of sustainable tourism development. The authors have found that the tourists supported sustainable tourism by purchasing local goods and thus helping the local economy. They also state that the tourists are more willing to donate to local conservation initiatives. This shows that there is an understanding of sustainable tourism in countries such as St. Lucia. However, the role of tour operators also plays a significant role and the authors have not studied the perception of tour operators towards sustainable development [

12].

The concept of sustainable tourism emerged in the 1980s with basic frameworks and according to Bramwell and Lane (1993) as a reactive concept in response to the negative impacts of tourism on the environment and the local culture [

26]. Later it received some critique and reconceptualization by various researchers such as Liu (2013) Saarinen (2006) and Ramesh (2002), [

7,

15,

36]. The second decade of sustainable tourism was more focused on the evolving model as a tool for development instead of a reactionary concept. It has emerged as a model capable of bringing change in society. Therefore, the definition of sustainable tourism has improved a lot to a broader one stating that sustainable tourism meets the needs of present tourists without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs in such a way that monetary, societal, and artistic needs can be fulfilled [

27].

Sindiga (1999) studied the alternative sustainable development model in Kenya [

37]. Other countries were also studied by various scholars such as Turkey, Egypt, and North Cyprus by Tosum [

38] Shalaan [

39], and Altinay and Hussain [

40] respectively. The later models highlight sustainable tourism as clean and green tourism with where firms do their best to avoid negative impacts on the environment. The triple bottom line (TBL) approach was put forth as a model by Dwyer et al. [

40], where the social, economic, and environmental aspects of tourism were highlighted. Reddy (2008) studied the economic dimensions of tourism such as taxes, foreign exchanges, wages, seasonality, and local economic benefits [

41].

The sustainable tourism models also evolved with respect to governmental policies. Sustainable and eco-friendly tourism is now part of the policy papers issued by various governments. Bowman (2011) indicated the need for certifications and policies around sustainable tourism [

42]. Local stakeholders are now involved in developing tourism strategies in some parts of the world. Community-managed tourism is another model that has emerged due to the sustainability aspect of tourism. Rural tourism has been promoted now because the benefits of the increased economic activity can reach rural areas and thus rural areas develop accordingly [

43]. Climate change has also been a matter of concern in few tourism researches but climate change is not fully understood in the tourism industry [

44].

The report of the World Commission on Development and Environment (WCED), defined sustainable development as, “Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generation to meet their own needs” [

5]. Sustainability and corporate social responsibility (CSR) emphasize the need for development and environmental safeguard while seeking economic growth and profit [

6]. Sustainability is now a topic of concern in every sector and the tourism sector is also one of them [

7]. The tourism sector mainly comprises the buyers of services and products (tourists) and the intermediaries who make the services and products (tour operators and others) available to the tourists [

8]. Tour operators being the main player in the sector providing tour packages and services are the major focus of this study. The primary role of tour operators in stimulating sustainable tourism is very important [

9]. The Tour Operators Initiative (TOI), has especially been designed for tour operators around the globe. TOI was developed by the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP); the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); and the UNWTO already in 2000 [

10,

11]. This inventiveness has a global scope and reassures tour operators to incorporate environmental, cultural, and societal deliberations in the design of tourism suites and their operations [

11,

12].

Some researchers such as Mannings (1992) have outlined the role of legislation, policy, and regulation in sustainable tourism but have no reference to the intermediaries such as the tour operators or travel agents [

13]. Tour operators have a substantial impact on the way tourism has developed in the past thirty years in many destinations [

2]. Being intermediaries in the supply chain, several authors have highlighted the interest of tour operators in promoting environmental management (green management) in tourist destinations [

14]. Several studies show that tour operators can play a significant role in employing sustainable practices in the tourism sector as mentioned by [

11]. In the tourism sector, tour operators provide a critical link between supply and demand. They join hands with several organizations and provide a package to tourists at a single price [

12]. Given the importance of the role of tour operators in promoting sustainable tourism, the Tour Operators Initiative (TOI) has been launched in 2000 by United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP); United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO); and the UN World Trade Organization (UNWTO) [

7].

Tourism is considered to be one of the driving forces for economic development [

15]. Tourism boosts foreign exchange and generating employment opportunities, the benefits of tourism cannot be negated as the literature proves that an increase in tourism activities leads to increased economic activity [

16]. There is a positive impact of tourism on employment [

17]. Using annual time series data from 1971–2008 from Pakistan, Adnan Hye and Ali Khan [

18] concluded that there is a long-term correlation between tourism income and the economic development of Pakistan. Tourism has also been noticed to have negative impacts on the environment if not managed sustainably. Lenzen et al. [

19] have stated that the tourism industry also contributes to the greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions by 8%. The study further predicts the emissions to reach 12% which is detrimental to the environment and ultimately will add to global warming.

According to various researchers [

20,

21,

22] sustainable tourism focuses on socioeconomic and environmental improvement that aims at the enhancement of tourist experiences. According to Buckley [

23] the term ‘sustainable tourism’ was used two decades ago for the first time. During the first 10 years, basic frameworks were studies from backgrounds in tourism, economics, and environmental management. After that, the second decade produced several conceptualizations and critiques including Liu [

24], Lane [

25], Sharpley [

20], and Bramwell and Lane [

26]. There are several definitions of sustainable tourism. However, the one mostly used in literature is the famous definition, which states that sustainable development is a development that fulfills the needs of the present minus compromising the capability of future generations to meet their own needs. The World Tourism Organization (WTO) defines sustainable tourism as something that meets the needs of present tourists and host regions while at the same time protecting and enhancing opportunities in the future. The resources are managed in such a way that the social, economic, and environmental aspects are taken care of [

27]. The Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) Criterion has been created to provide a common understanding of the concept of ‘sustainable tourism’ and are a set of least criterion that are endorsed to be met by those aspiring to develop sustainable tourism activities [

28].

The industry of tourism encompasses a varied range of different sub-sectors and services and every player wants to pursue their business interests or profit maximization goals. Among these players are the tourism enterprises such as hotels, tour operators, restaurants, destination management organizations (both private, public, and both), and local residents or communities. These different kinds of interests can often be conflicting [

29]. Every entity wants to have its own greater market share. It is believed that everybody wishes for extra business and a larger market portion [

30]. According to Carey et al., tour operators are not very interested in the development for decades to come (long term) [

2]. The focus merely on the short-term and seasonal gains. This leads to unsustainable tourism. While sustainable tourism focuses on longer-term impacts on the environment, society, and culture. The tour operators control the whole tourism experience from marketing to providing all services. Tour operators do not have any ownership or sense of responsibility towards the destinations and they only choose on what market segments to focus on. This leads to a situation where the tour operator usually focuses on a destination and moves to another destination after reaping all the benefits or financial gains [

31]. Sustainable tourism, however, depends upon the operators as well as the destination or local community. A varying degree of involvement from both sides is necessary to ensure sustainable tourism [

32].

Harrison et al. has mentioned practical encounters of sustainable tourism development in developing countries such as the Caribbean [

33]. The study suggests that for sustainable tourism more integrated planning was needed between tourism practitioners, academics, and government officials. Secondly, the vision is necessary at a high government level to decide what kind of tourists the country plans to attract. Some responsible tourists would like to avail the services of the tour operators. Kennett-Hensel et al. assessed the feedback they received from the managers of tour companies in Jamaica to develop the country’s master plan for tourism development and this master plan focused on conserving biodiversity and promoting cultural heritage [

34]. The master plan also discusses the Global Sustainable Tourism Criterion.

Nicholas and Thapa [

35] have analyzed the tourists’ perceptions of sustainable tourism development. The authors have found that the tourists supported sustainable tourism by purchasing local goods and thus helping the local economy. They also state that the tourists are more willing to donate to local conservation initiatives. This shows that there is an understanding of sustainable tourism in countries such as St. Lucia. However, the role of tour operators also plays a significant role and the authors have not studied the perception of tour operators towards sustainable development [

12].

The concept of sustainable tourism emerged in the 1980s with basic frameworks and according to Bramwell and Lane (1993) as a reactive concept in response to the negative impacts of tourism on the environment and the local culture [

26]. Later it received some critique and reconceptualization by various researchers such as Liu (2013), Saarinen (2006), and Ramesh (2002) [

7,

15,

36]. The second decade of sustainable tourism was more focused on the evolving model as a tool for development instead of a reactionary concept. It has emerged as a model capable of bringing change in society. Therefore the definition of sustainable tourism has improved a lot to a broader one stating that sustainable tourism meets the needs of present tourists without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs in such a way that monetary, societal, and artistic needs can be fulfilled [

27].

Sindiga (1999) studied the alternative sustainable development model in Kenya [

37]. Other countries were also studied by various scholars such as Turkey, Egypt, and North Cyprus by Tosum [

38], Shalaan [

39], and Altinay and Hussain [

40] respectively. The later models highlight sustainable tourism as clean and green tourism with where firms do their best to avoid negative impacts on the environment. The triple bottom line (TBL) approach was put forth as a model by Dwyer et al. [

40] where the social, economic, and environmental aspects of tourism were highlighted. Reddy (2008) studied the economic dimensions of tourism such as taxes, foreign exchanges, wages, seasonality, and local economic benefits [

41].

The sustainable tourism models also evolved with respect to governmental policies. Sustainable and eco-friendly tourism is now part of the policy papers issued by various governments. Bowman (2011) indicated the need for certifications and policies around sustainable tourism [

42]. Local stakeholders are now involved in developing tourism strategies in some parts of the world. Community-managed tourism is another model that has emerged due to the sustainability aspect of tourism. Rural tourism has been promoted now because the benefits of the increased economic activity can reach rural areas and thus rural areas develop accordingly [

43]. Climate change has also been a matter of concern in few tourism studies, but climate change is not fully understood in the tourism industry [

44].

Tourism in Pakistan

Tourism in Pakistan is also connected to tourism in South Asia in several ways. South Asia is considered to be a prominent region with distinctive landmass, forests, rivers, mountains, beaches, rural tourist spots, and different climatic zones [

45]. In South Asia, there are eight countries out of which Pakistan also holds a significant position in terms of tourism. Most of these countries are developing countries and hence have a good potential to exploit the tourism sector as a growth sector and tourism industry as a tool for sustainable development. In terms of GDP in South Asia, the share of the tourism sector was 8.9% in 2017 [

46].

In Pakistan, the existing literature on tourism management discloses that the first-ever official interest in tourism in Pakistan seems to start in the 1960s when Mohammad Ayub Khan was the president [

3]. Through his leadership, few tourist information centers were set up in Pakistan. In 1965, the Master Plan for the Development of Tourism in Pakistan (1965–1985) was prepared through funding from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) [

18]. However, tourism was included in the policy-making level in 1972. In 1972 ministry of minority, religious affairs, and tourism came into being. This ministry was later changed and in 1976 when the tourism division became part of the ministry of commerce. In the year 1970, the Federal government created the Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation (PTDC) [

47]. The mandate of PTDC was to improve tourism groundwork and promote Pakistan as a tourist destination in the foreign market. In the year 1977, the ministry of culture, sports, tourism, and archeology was created. Since then, nothing changed and remained the same. In the year 1990, the formulation of national tourism policy took place and some work was done however as isolated projects as the available literature suggests [

3,

48].

Looking at the development of tourism as an industry in Pakistan, since the 1970s Pakistan has been known as a tourist destination. Amplified uncertainty due to the war in Afghanistan in the 1980s and discontent led to a descending coil of Pakistan’s tourism. A study carried out by Khalid Khan shows that the major factors for tourist inflow declination are political instability, lack of tourism marketing, lack of associated services such as transport, and regional isolation of some of the tourist destinations [

49].

The rescue has been sluggish and was only momentarily realized in the years between 2004 and 2008. In 2009, Pakistan was ranked 113 out of 130 countries to visit, according to the World Economic Forum’s Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report (TTCR) [

50]. The overall rank of Pakistan indicates that the current position of Pakistan in the tourism sector is below average due to several reasons. Some concerns in this regard are business environment, safety and security, ICT readiness, human resource, and labor market, and health and hygiene where also Pakistan is ranked low. The air transport infrastructure (99 out of 136 countries) is also a matter of concern for the tourism in Pakistan [

3]. One of the positive features for tourists in Pakistan includes being an affordable destination. Domestic tourism has therefore been increasing in Pakistan. In a developing country, domestic tourism is more developed than international tourism [

3]. In Pakistan, in the year 2009, about 46 million domestic tourists availed themselves tourism services in one form or the other [

51] and 50 percent of these tourists were social travelers and 14% traveled for recreational purposes. However, foreign tourists have also been coming to Pakistan with varying numbers. World Tourism Organization (WTO) states that, in the year 2014, 1133 million foreign tourists were moving around the globe. The total number of foreign tourists coming to Pakistan in the year 2014 was roughly one million [

48]. On a global scale, the share of Pakistan in international tourism is very low. Compared within South Asia, Pakistan’s share out of 18.26 million overseas tourists was 6.7% compared to India’s share of 46% and 44% of the total tourists coming to Pakistan were from Europe [

52]. A good number of religious tourists in the form of Sikhs came to Pakistan while 50 percent of foreigners came to Pakistan to visit their family and friends. Religious events are also stimuli to intra-regional and domestic tourism. Across South Asia, including Pakistan, people from other countries also travel to countries having religious significance to them [

51]. For example, Buddhists visit Sri Lanka and Nepal, Muslims travel to Mecca [

53].

In the year 2000, a comprehensive master plan for tourism was drafted for Pakistan with the support of the World Tourism Organization (WTO) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) [

3]. In the year 2010, the tourism ministry conscripted a broad national tourism policy and recognized challenges and limitations for the tourism industry in Pakistan with marketing and development challenges [

54]. This policy also highlighted the importance of public-private partnerships for tourism development. The draft tourism policy 2010 was more comprehensive than the one drafted in 1990 however due to the dissolution of the federal tourism ministry because of the 18th Amendment in the constitution of Pakistan the work was left incomplete [

46]. The tourism policy 2010 was had many clauses indicating the importance of sustainable tourism in Pakistan. After the 18th amendment in the constitution of Pakistan, the federal ministry being abolished created a vacuum for watching the tourism sector affairs at the national level. Some issues can only be resolved at the federal level such as establishing the international image, laws around environment protection, ecotourism, and tourist visas [

3]. The tourism segment has not been given its owing respect at the federal and provincial level and this has been validated by the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2015 [

55]. Pakistan’s score was 120 with respect to prioritization of the travel and tourism industry, which further dropped to 122 in 2017 [

56].

Sustainable tourism demands certain rules and regulations to be in place to safeguard the environment and culture. Currently, the hotels and restaurants being the major businesses in the tourism sector, are not implementing certification and standards [

3]. The major laws in Pakistan are the Pakistan Tourist Guides Act 1976, the Travel Agencies Act 1976, and the Pakistan Hotels and Restaurants Act 1976 [

57]. These are very broad acts and have given very little space to sustainable tourism. The act that is more relevant to this study is the Travel Agencies Act, because it directly relates to the tour operators in Pakistan. However, the travel agencies act also focuses more on fees, licenses and not on environmental protection and social responsibility. There is also weaker implementation of criterion or certifications on the ground. The responsibility of implementing these laws lies with the Department of Tourist Services (DTS). Prior to the 18th amendment, DTS used to work under the federal ministry, and now, it is a provincial entity [

57]. A Star System also exists for standardizing the quality of services offered by the tour operators and hoteliers but implementation has remained a challenge with respect to sustainable tourism in Pakistan. Without laws and strict implementation, it is hard to achieve the targets of sustainable development.

In summary, the literature review raises important issues that need further investigation in the context of Pakistan in particular and overall global sustainable tourism in general. Particularly with reference to Pakistan, there seems to be a dearth of literature regarding sustainable tourism development. Pakistan is an attractive tourist destination due to its cultural, religious, adventure, and geographic tourism sites. However, due to terrorism, tourism became adversely affected from 2000 to 2017 [

58,

59] and presently tourism is in the renaissance phase [

60] and lacks sustainability.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

The in-depth interviews with the managers of the selected tour operators in Pakistan highlight a wide gap and dire need for incorporating the Global Sustainable Tourism Council Criterion and the sustainability measures. The TOs seem to understand the need for sustainability measures and realize the genuine concern. However, the TOs do not find a quick incentive to implement them. Some of the mature do show concern about the environment and the need for responsible tourism. However, most of the TOs need capacity building, incentives, and laws to be more responsible.

There is also a need to differentiate between social responsibility and sustainable tourism management. The TOs take social responsibility as a marketing stunt and allocate some funds for some social event or support. While sustainable tourism management means adhering to the GSTC criterion and restructuring the tour company around the guidelines provided by the WTO and GSTC.

The tour operators show a concern for the environment and the cultural heritage but there is found to be no incentive for the tour operators to drop tourists who would damage the environment and cultural heritage. The incentive is very long-term thus unrealized by TOs. Therefore, there must be government initiatives to avoid the negative impact. One such example is the tourism police that is now being tested by the provincial government of Khyber Pakhtoonkhwa.

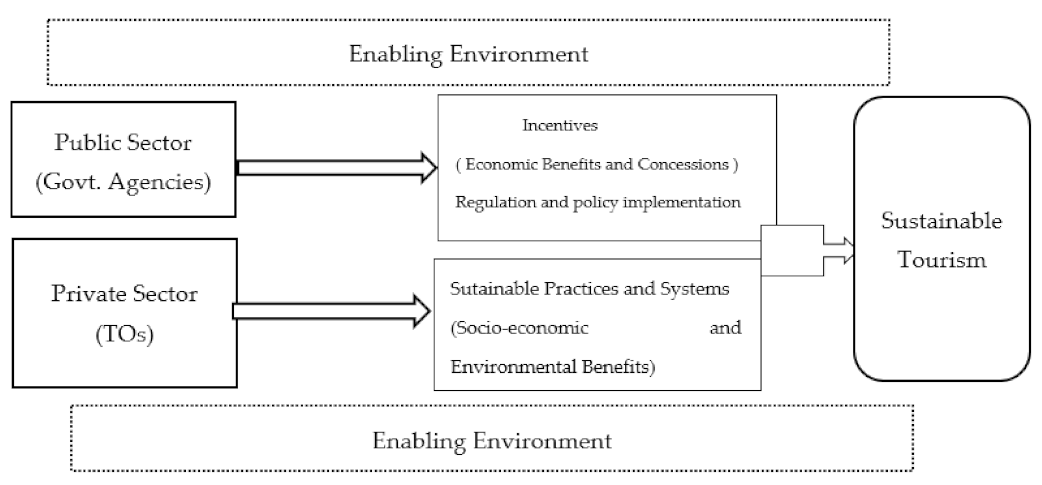

Below the authors have put together a model for the development of sustainable tourism in Pakistan through TOs based on the discussion and analysis of data from the in-depth interviews conducted.

In the below model,

Figure 1, the authors suggest that sustainable tourism can be developed in Pakistan by putting the right incentives in place through the government agencies and adopting sustainable practices through the TOs.

The incentives could be occasional concessions such as discounts on tour operators’ licenses, relaxation in tax filing, ease of registration (extending deadlines, etc.) provided to the TOs for adopting sustainable practices. Sustainable practices and systems that need to be adopted by the TOs should be aligned with the GSTC criterion. Some of the sustainable practices based on the GSTC could be; consideration to environmental risks in the host regions, documentary evidence of compliance to environmental laws, annual sustainability report or due consideration to sustainability in external communication, site selection taking into account the cultural and natural conservation, etc. It forms a strong case that these two factors (provision of incentives and adoption of sustainable practices) when done in close relation to each other could lead to the development of sustainable tourism. This is also justified by the incentive theory of motivation put forth by many behavioral scientists such as B.F. Skinner. Once the TOs in particular and the society, in general, realize the benefits of sustainable practices, the TOs would be in a position to stick to the globally accepted practices for their profitability and sustainability. However, this strategy needs to be supported by an enabling environment throughout. The government needs to put in place laws (environmental, sustainability) and act in a supportive role to the private sector or TOs. This can include ease of registration, compliance, relief packages to TOs during circumstances such as pandemic COVID-19, and capacity building of TOs on the rules, regulations, and GSTC recommended practices. An enabling environment minimizes risks for the TOs and encourages measures required for sustainable development. The political and economic stability within the country in general and in the tourist zones in particular also play a key role in the overall enabling environment needed for the model to work. In the context of Pakistan, an emerging nation trying to move from terrorism to tourism, it is very important that tourism is based on strong foundations of sustainability. Otherwise, the negative impact of mass tourism on Pakistan will one day overshadow the economic gains of the private TOs. One possible limitation of the current study is that it used a qualitative approach only; however, in future studies, it is suggested that our proposed model needs to be tested under a quantitative research design that will definitly give better generalizability.

5.1. Summary of Findings

The majority of the TOs in Pakistan lack an understanding of the GSTC criterion.

The TOs seem to understand the concept of sustainability however a deep understanding with an intention for change or implementation is lacking.

The TOs seems to realize the gravity of the negative impacts of mass tourism on the environment and cultural heritage but do not find any short term gains or incentives to apply GSTC criterion for tourism management.

Few of the TOs train local guides and thus imparting education to the local communities.

There TOs are more concerned by the TOs license, which is a license to operate a tour agency and does not have any reference to sustainable tourism.

The TOs consider their role as important in developing sustainable tourism in Pakistan however highlight the need for education (awareness, training) and laws.

For the development of sustainable tourism in Pakistan, the public sector (govt. agencies) and private sector need to work together within a framework of incentives, sustainable practices and enabling environment.

In some of the areas, such as having a sustainable tourism management system in place, the TOs seem to agree more about the lack and thereof to the need for such a system; however in other areas, such as environmental protection, the TOs do not have any mechanism in place to control tourists behaviors.

5.2. Recommendations

5.2.1. Implications for Researchers

A broader study needs to be conducted to grasp a better and realistic understanding of the role of tour operators in developing sustainable tourism in Pakistan. The sample needs to be extended to gather more information from a larger pool of tour operators (TOs). The different aspects of sustainability such as environment, culture, and economics need to be brought under research to add to the body of knowledge and find the gap between what is known, unknown, practiced, not practiced in the tourism sector. A greater number of organizations from different categories defined under Small and medium enterprise laws should be taken into consideration with robust research methodology. Researchers can come up with results of paramount importance for developing countries such as Pakistan.

It is important to understand that attracting international tourists is a challenging task for the tourism industry in Pakistan. Terrorism and one and half decade long war on terror destroyed tourism in Pakistan. Visitors were killed and tour destinations were bombed. Hotel and transport services were insecure. The media added fuel to the fire by projecting such situations with even exaggeration. The fear still prevails even after the situations have turned normal and many tourists avoid visiting Pakistan. After 2016, conditions have been peaceful and perfectly conducive for tourism. It is the need of the hour to portray the real picture to tourists and encourage them to consider Pakistan for tourism and it is the joint responsibility of the government and the tour operators. It is established that tour operators have a definite role in developing sustainable tourism while the findings of our study depict no significant role of tour operators in the rehabilitation of sustainable tourism in Pakistan. The need of the day is to research to find out how to make TOs to realize their role in developing sustainable tourism, to motivate them to play their role and leading them to the right track.

The model developed in this study provides a conceptual basis for the development of sustainable tourism in Pakistan. Therefore, the model given in this paper can be used as a launchpad for the development of sustainable tourism. Furthermore, based on this framework, the ground can be set for further research and practice on various other dimensions such as the co-relation between enabling environment and sustainable tourism development, incentivizing tourism sector for sustainable development, community managed tourism versus TOs led tourism, etc.

The findings of this study can be used as a basis for desigining other research methodolgies in the context of Pakistan and sutainable tourism such as mixed method. A quantiative study might be developed based on the framework developed here to quantify the benefits of sustainable tourism in terms of revenue, profits and other social and environmental gains (such as reduction of carbon foot print).

5.2.2. Implications for Practitioners

The TOs in Pakistan need to adopt the GSTC criterion for a better tourism sector. Sustainable practices would lead to a better environment, preserved culture, and local economic development. The unsustainable practices would damage the environment, cause losses in the longer term and create violence in the local communities towards the tourists. The managers of TOs need to design systems for sustainable tourism practices. This could mean having a risk matrix in place for the activities, tourist guidelines focused on environment and local culture, reporting on sustainability, etc. Indeed, such initiatives would add to the overall cost of designing a tour package; however, the long term benefits of such systems cannot be overruled.