Abstract

Recognizing the importance of knowledge sharing, this study adopted social learning and social exchange perspectives to understand when employees may engage in knowledge sharing. Using data collected from 192 employees in various South Korean organizations, the findings demonstrate that there is a positive relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing. As employees perceive a high level of supervisor knowledge sharing, they are likely to engage in knowledge sharing based on social learning and social exchange theories. Furthermore, the study explores the moderating effects of learning goal orientation and affective organizational commitment in the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing. The result supports the hypothesis that the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing is strengthened when there is a high level of affective organizational commitment. Employees who obtain valuable knowledge from their supervisors are likely to engage in knowledge sharing when they are emotionally attached to their organization. However, in contrast to the hypothesis, the positive relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing was stronger at the lower levels of learning goal orientation (LGO) than at the higher levels of LGO.

1. Introduction

Knowledge sharing is vital if organizations are to sustain themselves in a highly competitive and dynamic environment [1,2,3,4,5]. Scholars have acknowledged the benefits of knowledge sharing on innovation and performance [6,7]. As Simon [8] stated, “all learning takes place inside individual human heads (p. 125), it is important to facilitate knowledge sharing at the individual level. However, despite the positive impacts of knowledge sharing, employees may be reluctant to perform such behaviors [9,10]. Given that knowledge is regarded as a unique resource of each individual, employees may fear losing their competitive advantage through sharing their knowledge [11]. Thus, it is necessary that employees should have motivations or reciprocity to engage in knowledge sharing [12,13,14].

Given the high status and position of the supervisor, supervisors are key actors who can provide valuable resources and act as role models to their employees [1,15]. When supervisors share their valuable knowledge, experts, and skills with employees—a process regarded as supervisor knowledge sharing—the knowledge recipients who obtain the necessary resources are likely to feel appreciated and learn this behavior. Thus, this study applies social learning and social exchange theories to explore under what conditions employees may decide to engage in knowledge sharing, investigating supervisor knowledge sharing as a key determinant. Although the body of research on this topic has contributed to the understanding of knowledge sharing, the literature is still limited in significant ways.

First, there is a paucity of studies investigating the effects of supervisors’ knowledge sharing on outcomes. Understanding the important role of supervisor behaviors on employees’ attitudes and behaviors, scholars have examined how various supervisor behaviors are related to employee knowledge sharing [10,16]. For example, empowering behaviors from a supervisor are positively related to knowledge sharing [16], whereas abusive supervisor behavior is negatively related to knowledge sharing [10,17,18]. However, despite its relevance, supervisors’ specific behaviors, such as knowledge sharing behavior, have not yet been investigated as a predictor of employee knowledge sharing. To fill this gap, the current study examines the positive link between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing.

Second, social learning theory [19] has not been applied very extensively to explain the knowledge sharing process, despite its usefulness [1]. Prior research stated that prior research has mainly used social exchange theory, as well as social capital and network perspectives, to explain when employees willingly share their knowledge with others [7]. Compared to other prosocial behaviors, it is riskier and more challenging to engage in knowledge sharing, since knowledge could be viewed as a competitive advantage for each individual [10,11]. From this respect, it is important that supervisors show exemplary behavior to encourage employees’ knowledge sharing [1].

According to social learning theory [19], individuals tend to learn work behaviors by observing others in the workplace. Considering the strong influence of supervisors, employees may view their supervisors as role models and learn the behaviors from watching how their supervisors behave in the workplace [20,21,22]. In this regard, employees who receive valuable knowledge from their supervisors may view the supervisors as appropriate role models and may attempt to learn their knowledge-sharing behaviors, based on social learning theory. Thus, the goal of this study is to examine how employees learn supervisors’ knowledge-sharing behavior and imitate such behavior accordingly based on social learning theory.

A third limitation of the existing literature is that only a few studies have examined contingent factors that influence how and when knowledge sharing may be most successful in promoting employee knowledge sharing [10,23]. Although supervisors offer valuable knowledge to their employees, employees may not fully enjoy the benefits of supervisor knowledge sharing depending on the situational factors, such as characteristics of the knowledge recipients, and various organizational factors. It is meaningful to examine such boundary conditions because such an investigation can advance our knowledge on the effect of supervisor knowledge sharing. As an individual factor, this study selects learning goal orientation (LGO), which is defined as “an internal mindset that motivates an individual to develop his or her competence” [24] (p. 767). When supervisors share their valuable knowledge or information with their employees, employees may learn new methods or develop their skills. Then, employees with high LGO are likely to perceive more benefits from the knowledge shared by their supervisor since it matches with their LGO characteristics. As a result, it is expected that high LGO may strengthen the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing.

In addition, this study explores the moderating role of affective organizational commitment, which describes how employees are emotionally attached to and identified with the organization [25]. Affective organizational commitment is known to bring positive effects to employee outcomes [26,27]. However, prior research has not paid much attention to the role of affective organizational commitment in influencing the knowledge-sharing process. To address this question, the current study suggests that employees who obtain valuable knowledge and expertise from their supervisors, as well as from their organization, are likely to engage in knowledge sharing as a return for positive reciprocity, drawing on social exchange theory [28].

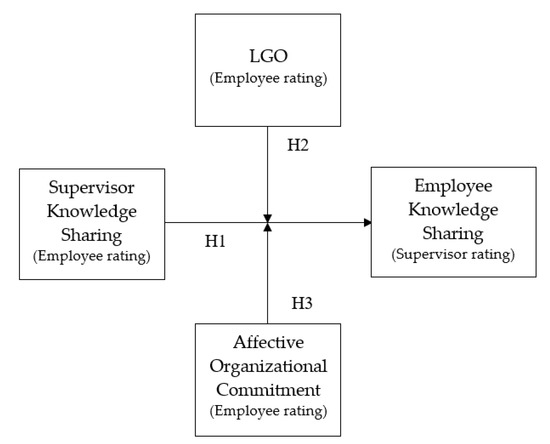

In summary, this study has two major research purposes. First, this study contributes to the knowledge-sharing literature by exploring supervisors’ knowledge-sharing behavior as a predictor of employee knowledge sharing. In addition to social exchange theory, this research applies social learning theory to deepen the understanding of knowledge sharing. Second, this study investigates LGO as an individual moderator, and affective organizational commitment as an organizational moderator, in the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing. Specifically, this study seeks to find under what conditions supervisor knowledge sharing may be most effective in promoting employees’ knowledge sharing. Figure 1 depicts our model.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Supervisor Knowledge Sharing and Employee Knowledge Sharing

Knowledge sharing, “a team process defined as team members sharing task-relevant ideas, information, and suggestions with each other” [16] (p. 1239), has been known as a critical behavior that affects organizational effectiveness. Despite the contributions of knowledge-sharing behaviors, employees may decide not to perform such behaviors because of their risky and resource-intensive nature [10]. From this perspective, employees must have the motivation or be able to see why they should engage in such knowledge-sharing behavior [17]. Prior research has found individual, leader, and organizational factors to be predictors of knowledge sharing [7]. In particular, employees may decide to perform discretionary behaviors, especially prosocial behaviors, depending on their supervisors [10]. Scholars have noted that supervisors have a critical effect on employees’ attitudes, behaviors, and performance [29]. Certainly, previous studies have demonstrated the significant effects of supervisor behaviors on knowledge sharing [13,16]. In line with previous research, this study argues that a supervisor’s prosocial behavior, particularly the supervisor’s knowledge sharing behavior, enhances employees’ knowledge sharing, based on social learning theory.

Social learning theory [19] suggests that employees may learn how to behave in the workplace from watching their role models. Employees are likely to choose role models who have attractive model characteristics [30]. Prior studies have identified nurturance, status, competence, and power as key model characteristics [30,31]. In a workplace, employees are likely to view their supervisor as a critical role model since the supervisor is likely to have high power, status, and competence [32]. In particular, a supervisor who shares his or her unique knowledge with others is viewed as an appropriate role model since he or she exhibits exemplary behavior which, in turn, may affect employee behavior [22]. Prior research has examined ethical leadership to be a potential antecedent of employee knowledge sharing because an ethical leader can offer the opportunities and motivation necessary for knowledge sharing [1].

Social exchange theory [28] posits that employees may determine their behaviors or attitudes towards their exchanging partners depending on their perceived support or benefits from their exchanging partners. Given knowledge as a competitive advantage in the workplace, supervisors sharing their unique knowledge could be seen as prosocial behavior to employees [33]. According to social exchange theory [28], knowledge recipients are likely to feel an obligation toward supervisors who share their valuable knowledge, and they may decide to engage in knowledge sharing as a form of reciprocity.

Therefore, employees working with a shared supervisor are likely to learn what is appropriate behavior in the workplace—what the norm is—and exert an effort to share their knowledge. It is because they feel an obligation toward their supportive supervisor and want to emulate the knowledge-sharing behavior based on social learning and social exchange perspectives. Thus, this study expects the following:

Hypothesis (H1).

Supervisor knowledge sharing is positively related to employee knowledge sharing.

2.2. The Moderating Effect of Learning Goal Orientation

Goal orientations have two separate independent types: learning goal orientation and performance goal orientation [34]. Individuals with an LGO, who emphasizes a “growth mindset,” put in an effort to gain competence; whereas individuals with a performance goal orientation who have a “fixed mindset” are eager to demonstrate their competencies to others [35,36]. A performance goal orientation was further classified into a performance-proven goal orientation, which focuses on proving their competence, and performance-avoid goal orientation, which focuses on avoiding poor competence [37,38]. Given its close relevance to knowledge sharing, the present study selects LGO as a critical individual factor and proposes the moderating effect of LGO in the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing, applying the social learning and social exchange perspectives.

Social learning theory highlights the importance of role models in the learning process by observing and emulating them [30]. Since a supervisor’s knowledge-sharing behavior is desirable behavior and fits with the learning orientation of employees, high LGO employees are more likely to view a supervisor who shares his or her knowledge as an appropriate role model. From this respect, the employees who regard their supervisor as a role model are predicted to learn and imitate this knowledge-sharing behavior based on social learning theory. As a result, those employees are likely to react more strongly because of the impact of the supervisor’s knowledge-sharing behavior on their own knowledge-sharing behavior.

In addition, high LGO employees are likely to obtain more benefits from shared knowledge from supervisors because of its LGO characteristics. Supervisors’ shared knowledge may not be very useful unless the knowledge recipients’ value and utilize the shared resources [39]. Since high LGO employees are interested in improving their competencies, learning new skills, and mastering various tasks [40], they may perceive the supervisor’s knowledge sharing as a learning opportunity to fulfill their orientation. From this respect, high LGO employees who tend to greatly value the knowledge shared by their supervisors are likely to feel more obligation toward their supervisor, compared to low LGO employees. Those employees may choose to engage in prosocial behavior such as knowledge sharing based on social exchange theory. Consequently, this research proposes the following:

Hypothesis (H2).

Learning goal orientation (LGO) moderates the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing such that the positive relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing is strengthened when LGO is high rather than when it is low.

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Affective Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment can be conceptualized as having three aspects: affective, continuance, and normative commitment [41,42]. According to the three-component model developed by Meyer and Allen [25], the reasons employees stay in an organization differ among the three aspects. For example, employees with high affective commitment tend to remain in the organization because they desire to do so. Employees with high continuance commitment may stay in the organization because the cost of leaving the organization is high. Employees with high normative commitment are likely to feel an obligation to stay in the organization. Prior research has noted that affective organizational commitment is positively related to job performance and job satisfaction, whereas continuance commitment is negatively or unrelated to such behaviors or attitudes [41,43,44]. This study explores affective organizational commitment as a critical organizational factor because of its significant positive impacts on various individual outcomes.

When employees perceive a high level of affective organizational commitment, they tend to have a deep emotional relationship and identify with the organization [45,46]. Since highly committed employees are likely to assimilate organizational values and goals as their own, previous research have noted the positive relationship between affective organizational commitment and prosocial behaviors such as organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) and knowledge sharing [27,47]. However, the moderating role of affective organizational commitment has not been examined extensively [26]. Applying social exchange theory [28], this research exhibits the role of affective organizational commitment in the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing.

As affective organizational commitment could be regarded as a valuable resource, employees who perceive a high level of affective organizational commitment may feel appreciative toward their organization [48]. In this respect, when they feel a high level of affective organizational commitment, employees who receive valuable knowledge from their supervisor are more likely to feel an obligation toward their supervisor as well as their organization. As knowledge sharing is regarded as beneficial behavior to the team and organization [10], those employees who receive valuable resources from both supervisor and organization are likely to share their knowledge as reciprocity, according to social exchange theory. As “greater commitment may engender beliefs that the organization has rights to the information and knowledge one has created or acquired” [49] (p. 156), employees working with supportive supervisors in emotionally attached organizations tend to share their knowledge. Therefore, this study offers the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis (H3).

Affective organizational commitment moderates the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing, such that the positive relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing is strengthened when affective organizational commitment is high rather than when it is low.

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

The study collected data from several organizations located in South Korea. The industry sectors included in this sample were mainly manufacturing, construction, service, and distribution, making up 70% of the sample. Survey packets, which included a cover letter outlining the study, a questionnaire, and a pre-addressed reply envelope, were prepared and distributed to all 250 supervisor–subordinate dyads. From 250 dyadic samples, 198 supervisor-employee dyads were returned, a response rate of 79.2%. Each supervisor was matched with only one employee; thus, all of the observations are independent with regard to the supervisor. Upon completion, each participant sealed the survey in a pre-addressed reply envelope provided and returned it directly to the researcher. Their participation was entirely voluntary.

After matching the supervisor and subordinate surveys, 193 pairs of matching surveys were collected and used as a final analysis, with a response rate of 77%. The subordinate sample was 81.9% male, with an average age of 36.6. The supervisor sample was 95.3% male, with an average age of 45.1. Most of the employees (94.3%) and supervisors (97.4%) held at least a bachelor’s degree.

3.2. Measures

The study used English-language questionnaires with established scales. Two Korean bilingual academics translated it into Korean independently using the conventional method of back-translation [50]. The focal employees were asked to rate their LGO, affective organizational commitment, and their perception of supervisor knowledge sharing. To reduce the concerns about common method bias, their immediate supervisors evaluated the focal employee’s knowledge sharing. All of the items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree).

Supervisor Knowledge Sharing. Srivastava and his colleagues’ [16] seven-item scale was used to measuring supervisor knowledge sharing. A sample item reads, “Supervisor in our team shares his/her special knowledge and expertise with one another” (α = 0.97).

Learning Goal Orientation (LGO). LGO was measured using five items developed by Brett and VandeWalle [37]. As a sample, one item was “I often look for opportunities to develop new skills and knowledge” (α = 0.91).

Affective Organizational Commitment. Affective organizational commitment was assessed with eight items developed by Allen and Meyer [51]. Participants were asked to react to statements such as “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization” (α = 0.88).

Employee Knowledge Sharing. Supervisors rated their employees’ knowledge sharing. To measure employees’ knowledge sharing, Srivastava and his colleagues’ [16] seven-item scale was used. A sample item for knowledge reads, “The subordinate shares his/her special knowledge and expertise with others” (α = 0.93).

Control Variables. Employees’ demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, and education, were controlled to minimize any spurious effects and be consistent with the extant literature [13]. In addition, prove-performance goal orientation (PPGO) and avoid-performance goal orientation (APGO) were measured using four items each from Brett and VandeWalle [37] and included control variables. The estimated reliabilities were 0.90 for PPGO and 0.82 for APGO. Sample items included, “I like to show that I can perform better than my coworkers” (PPGO) and “I would avoid taking on a new task if there was a chance that I would appear rather incompetent to others” (APGO).

4. Results

Tests of Hypotheses

Descriptive statistics, correlations, and Cronbach’s alpha for the variables are presented in Table 1. As expected, supervisor knowledge sharing was positively correlated with employee knowledge sharing (r = 0.16, p < 0.05). Furthermore, the study variables demonstrated high reliability with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.88 or higher.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and correlations among study variables.

To test the hypotheses, the study conducted hierarchical regression analyses. Hypothesis 1 proposed that supervisor knowledge sharing is positively related to employee knowledge sharing. As shown in Table 2 (Model 2), Hypothesis 1 was supported, as supervisor knowledge sharing was positively related to employee knowledge sharing (β = 0.16, p ≤ 0.05). Hypothesis 2 suggested the moderating effect of LGO in the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing. As shown in Model 4 of Table 2, the interaction between supervisor knowledge sharing and LGO was positively significant (β = −0.15, p ≤ 0.05). The interaction is plotted in Figure 2. It showed that the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and LGO was stronger when LGO was low rather than when it was high—which did not support Hypothesis 2. Hypothesis 3 predicted the moderating role of affective organizational commitment in the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing. The result, in Model 4 of Table 2, showed that the interaction of supervisor knowledge sharing, and affective organizational commitment was positively significant (β = 0.19, p ≤ 0.01). As Figure 3 illustrates, the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing was stronger when the affective organizational commitment was high than when it was low. Thus, the result supported Hypothesis 3.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regression results.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of learning goal orientation (LGO) on the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing.

Figure 3.

The moderating effect of affective organizational commitment on the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing.

5. Discussion

In a knowledge-based society, it is critical to encourage knowledge-sharing to achieve organizational effectiveness [3,4,5]. Integrating social learning and social exchange perspectives, this study examined supervisor knowledge sharing as a driver of employee knowledge sharing and its boundary conditions. Specifically, this research investigated LGO and affective organizational commitment as key moderators in the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing. The results support the main effect and the moderating effect of affective organizational commitment, but not the moderating effect of LGO. In contrast to the prediction, the positive relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing was stronger at the lower levels of LGO than at the higher levels of LGO.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, it contributes to knowledge sharing literature by investigating knowledge sharing from a specific source, such as the supervisor. Although knowledge sharing behavior is critical for promoting organizational effectiveness in our knowledge-based economy, there is limited research examining the various sources of knowledge sharing and its effects at the individual level [33]. Since knowledge sharing from different sources could bring different outcomes, it is important to examine the effects of knowledge sharing from various sources. Kim and Yun [33] have demonstrated the positive effect of coworker knowledge sharing on the task performance of employees. To fill a gap in the literature, this study shows how knowledge sharing from supervisors is a critical driver of employee knowledge sharing. Future research could further expand our understanding of supervisor knowledge sharing by examining other outcomes, such as task performance or creativity. Moreover, it would be beneficial to investigate mediating mechanisms in the aforementioned relationship in future research. Leader-member exchange (LMX) or leader trust could be a key mediator in the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing.

Second, this study adds insight to the leadership literature by exploring a specific supervisor’s behavior as a key predictor of employee knowledge sharing. Scholars have examined various supervisor behaviors as antecedents of knowledge-sharing behaviors such as empowering behavior, ethical behavior, and transformational behavior [1,2,16]. This study applied social learning and social exchange theories to show the positive link between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing. Earlier research has demonstrated the relationship between leader OCB and group OCB [22]. Scholars have noted that authentic leaders and inclusive leaders as role models are likely to lead followers’ vicarious learning of inclusive behaviors [20]. Bavik and colleagues [1] found that ethical leaders act as role models for their followers and encourage them to share their knowledge. In line with prior studies, this study showed that employees who observe and learn supervisors’ knowledge-sharing behavior decide to imitate the behavior, based on social learning theory. Future research may explore other supervisor factors and test how the role of supervisor factors may promote employees’ knowledge-sharing behaviors by watching and learning the behavior.

Moreover, this study exhibited how employees who obtain valuable knowledge from their supervisors are likely to feel an obligation towards their supervisors. Considering knowledge and information as one of the key resources in the social exchange framework [52,53], the focal employees working with those supervisors decided to share their knowledge as a return based on social exchange theory.

Lastly, the study investigated important contexts that shape the effects of supervisor knowledge sharing on employee knowledge sharing. Although supervisor knowledge sharing is beneficial to promote employee knowledge sharing, the positive impacts may not be identical, depending on individual and organizational factors. Prior research has investigated exchange ideology, self-efficacy, LGO, and the self-enhancement motive as moderators in the knowledge sharing process [17,23,33]. Specifically, this study explored LGO as an individual factor and affective organizational commitment as an organizational factor. This study finds that the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing is strengthened when there is a high level of affective organizational commitment. In future research, it could be worthwhile to explore other organizational factors, such as organizational justice and organizational support, as critical moderators that strengthen the aforementioned relationship.

Different from the prediction, the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing is strengthened when there is a low level of LGO.

There might be plausible reasons for this unexpected result. First, the result could be explained by the substitutes for the leadership model [54]. Kerr and Jermier [54] posit that the leader’s influence could be diminished when affecting employees’ attitudes or behaviors, depending on various situational factors such as subordinate, task, and organizational characteristics. In this respect, LGO could be one of the substitute variables for the effect of a supervisor’s knowledge-sharing behavior. Prior research has noted that the negative impact of abusive supervision on knowledge sharing was worsened when employees exhibit a low level of LGO [17]. In a similar vein, since employees with high LGO may already have the motivation to share their knowledge, they may engage in knowledge sharing regardless of the level of supervisor knowledge sharing. In this case, the supervisor’s knowledge sharing may not be required to enhance employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior based on the substitutes for the leadership model.

Second, the possible explanation could be a ceiling effect [55]. Since knowledge sharing fits with the characteristics of LGO, supervisors’ knowledge sharing behavior might not result in a significant increase in the level of employee knowledge sharing for employees who have high LGO. If this ceiling effect is occurring, the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing may be stronger in the low LGO condition than in the high LGO condition. This is because employees in the high LGO condition have reached a certain degree of employee knowledge sharing, as exhibited in Figure 3. Future research should consider these possibilities and directly test the substitution effect or ceiling effect.

5.2. Practical Implications

In addition to the theoretical contributions, the findings provide valuable practical implications as well. The study demonstrated the value of the social learning perspective to predict employee knowledge sharing. Specifically, the organization should understand the important role of supervisor knowledge sharing on employee knowledge sharing. Since it is one of the most important conditions for employee knowledge sharing, the organization should provide leadership training or coaching programs that may promote supervisors’ knowledge-sharing behavior.

Moreover, the organization should note the critical role of affective organizational commitment because it could strengthen the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing. Prior research has shown that high-commitment human resource (HR) practices and organizational support could be significant antecedents of affective organizational commitment [41]. Thus, the organization should invest resources to enhance HR practice and provide support to their employees, which could increase the level of effective organizational commitment.

Lastly, the study highlights the important role of LGO as a key factor in knowledge sharing. In contrast to our prediction, our result shows that high LGO employees are likely to engage in knowledge sharing regardless of the level of supervisor knowledge sharing. Although it is not hypothesized, the result illustrates the strong direct effect of LGO on employee knowledge sharing. From this respect, the organization should keep in mind the role of individual factors in the knowledge sharing process and use this information in assigning jobs that require knowledge sharing.

5.3. Limitations and Conclusion

As with most empirical studies, this one has limitations. First, reverse causality might be possible since the study is cross-sectional in design, which collected data at one point in time. It would be worthwhile to conduct a longitudinal study to ensure the direction of causality in future research. Second, the focal employees rated their LGO, affective organizational commitment, and their perceptions of supervisor’s knowledge sharing. Thus, it is possible that issues related to common method bias could occur. In order to mitigate common method bias, the research used diverse measures including employee and supervisor dyads. For example, employee knowledge sharing was rated by their immediate supervisor in this study. In future research, it would be worthwhile to measure supervisor knowledge sharing from multiple raters including supervisors. Additionally, it is noted that significant findings of interaction effects could reduce concerns about common method bias [56]. Lastly, this study examined only individual and organizational moderators to advance our understanding of the knowledge-sharing process. It might be fruitful to investigate diverse variables that may influence such processes in future research. For example, task and coworker characteristics could be significant moderators that may affect the relationship between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing.

Integrating social learning and social exchange perspectives, this study indicates under what conditions employees may engage in knowledge sharing. The findings highlight the importance of supervisor knowledge sharing as a key indicator of employee knowledge sharing and its important boundary conditions. As the results of this research shows, the positive link between supervisor knowledge sharing and employee knowledge sharing is strengthened when there is a low level of LGO and a high level of affective organizational commitment.

Funding

This work was supported by Incheon National University (International Cooperative) Research Grant in 2020.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Bavik, Y.L.; Tang, P.M.; Shao, R.; Lam, L.W. Ethical leadership and employee knowledge sharing: Exploring dual-mediation paths. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, A.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Shi, J.; Jin, Y. Team knowledge exchange: How and when does transformational leadership have an effect? J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerpott, F.H.; Fasbender, U.; Burmeister, A. Respectful leadership and followers’ knowledge sharing: A social mindfulness lens. Hum. Relat. 2020, 73, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; van Rijn, M.B.; Sanders, K. Perceived organizational support and knowledge sharing: Employees’ self-construal matters. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 2217–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.M.J.; Lin, C.H.V.; Ren, H. Linking core self-evaluation to creativity: The roles of knowledge sharing and work meaningfulness. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.J.; Smith, K.G. Knowledge exchange and combination: The role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Noe, R.A. Knowledge sharing: A review and directions for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2010, 20, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Bounded rationality and organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, E.F.; Cabrera, A. Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 16, 720–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L.; Kim, M.; Yun, S. Knowledge Sharing, Abusive Supervision, and Social Support: A Social Exchange Perspective. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 599–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, A.; Cabrera, E.F. Knowledge-sharing dilemmas. Organ. Stud. 2001, 23, 1687–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L.; Han, S.; Son, S.Y.; Yun, S. Exchange ideology in supervisor-subordinate dyads, LMX, and knowledge sharing: A social exchange perspective. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2017, 34, 147–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Kim, S.L.; Yun, S. A social exchange perspective of abusive supervision and knowledge sharing: Investigating the moderating effects of psychological contract fulfillment and self-enhancement motive. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinholt, M.I.A.; Pedersen, T.; Foss, N.J. Why a central network position isn’t enough: The role of motivation and ability for knowledge sharing in employee networks. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 1277–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offergelt, F.; Spörrle, M.; Moser, K.; Shaw, J.D. Leader-signaled knowledge hiding: Effects on employees’ job attitudes and empowerment. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Bartol, K.M.; Locke, E.A. Empowering Leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1239–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L.; Lee, S.; Yun, S. Abusive supervision, knowledge sharing, and individual factors. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 1106–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.L.; Yun, S. A moderated mediation model of the relationship between abusive supervision and knowledge sharing. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Boekhorst, J.A. The role of authentic leadership in fostering workplace inclusion: A social information processing perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 54, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A.; Misati, E. Does ethical leadership enhance group learning behavior? Examining the mediating influence of group ethical conduct, justice climate, and peer justice. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 72, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaffe, T.; Kark, R. Leading by example: The case of leader OCB. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 806–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-P. To share or not to share: Modeling knowledge sharing using exchange ideology as a moderator. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Huang, J.C.; Farh, J.L. Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhou, Z.E.; Che, X.X. Effect of workplace incivility on OCB through burnout: The moderating role of affective commitment. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 34, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzu-Shian, H.; Hsu-Hsin, C.; Aihwa, C. Employee participation in decision making, psychological ownership and knowledge sharing: Mediating role of organizational commitment in Taiwanese high-tech organizations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 2218–2233. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, P.; Matz, S.; Göritz, A.S. An integrative model of leadership behavior. Leadersh. Q. 2017, 28, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Do role models matter? An investigation of role modeling as an antecedent of perceived ethical leadership. J. Bus. Ethics. 2014, 122, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, A.; Vergel, A.I.S. Modelling job crafting behaviours: Implications for work engagement. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.L.; Yun, S. The effect of coworker knowledge sharing on performance and its boundary conditions: An interactional perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Leggett, E.L. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 95, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, P.A.; King, V.; Hood, M.; McKenzie, R. Goal orientation, self-regulation strategies, and job-seeking intensity in unemployed adults. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brett, J.F.; VandeWalle, D. Goal orientation and goal content as predictors of performance in a training program. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, B.; van Knippenberg, D.; Hirst, G.; Restubog, S.L.D. Outperforming whom? A multilevel study of performance-prove goal orientation, performance, and the moderating role of shared team identification. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1811–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulanski, G. Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.R.; Choi, J.N.; Butt, A.N. Distinct effects of intrinsic motivation and extrinsic rewards on radical and incremental creativity: The moderating role of goal orientations. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, Z.A. Affective commitment as a core essence of organizational commitment: An integrative literature review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2015, 14, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Herscovitch, L. Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Becker, T.E.; Vandenberghe, C. Employee commitment and motivation: A conceptual analysis and integrative model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 991–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sungu, L.J.; Weng, Q.; Hu, E.; Kitule, J.A.; Fang, Q. How Does Organizational Commitment Relate to Job Performance? A Conservation of Resource Perspective. Hum. Perform. 2020, 33, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Waeyenberg, T.; Peccei, R.; Decramer, A. Performance management and teacher performance: The role of affective organizational commitment and exhaustion. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Sleebos, E. Organizational identification versus organizational commitment: Self-definition, social exchange, and job attitudes. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, R.R.; Wright, P.M. The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 366–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Maltin, E.R. Employee commitment and wellbeing: A critical review, theoretical framework and research agenda. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Staples, D.S. Exploring perceptions of organizational ownership of information and expertise. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. Applied Cross-Cultural Psychology; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. Organizational socialization tactics: A longitudinal analysis of links to newcomers’ commitment and role orientation. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 847–858. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S.; Jermier, J.M. Substitutes for leadership: Their meaning and measurement. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1978, 22, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Caligiuri, P. The effectiveness of expatriate coping strategies: The moderating role of cultural distance, position level, and time on the international assignment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.G. A Monte Carlo study of the effects of correlated method variance in moderated multiple regression analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 36, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).