Political Instability Equals the Collapse of Tourism in Ukraine?

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- elaboration on how political and other events of national importance influenced tourism performance in the last two decades,

- (2)

- identification of the role of the Crimea in inbound tourism,

- (3)

- identification of changes in income from the use of tourist services by foreigners in Ukraine,

- (4)

- identification of changes in the accommodation sector at the provincial level compared to data prior to recent political instability,

- (5)

- to show possible lost opportunities associated with the most recent conflict,

- (6)

- to explore differences in perception of political instability on tourism on a local level by experts,

- (7)

- to reveal the perception of threats arising from the recent conflict in developed and undeveloped tourist localities,

- (8)

- indication of possible scenarios for tourism development in the future, and opportunities for tourism development.

2. Political Instability and Tourism—Literature Review

3. Research Purpose and Methods

3.1. Secondary Data

3.2. Primary Data Collection

4. Research Results—Effects of Political Instability

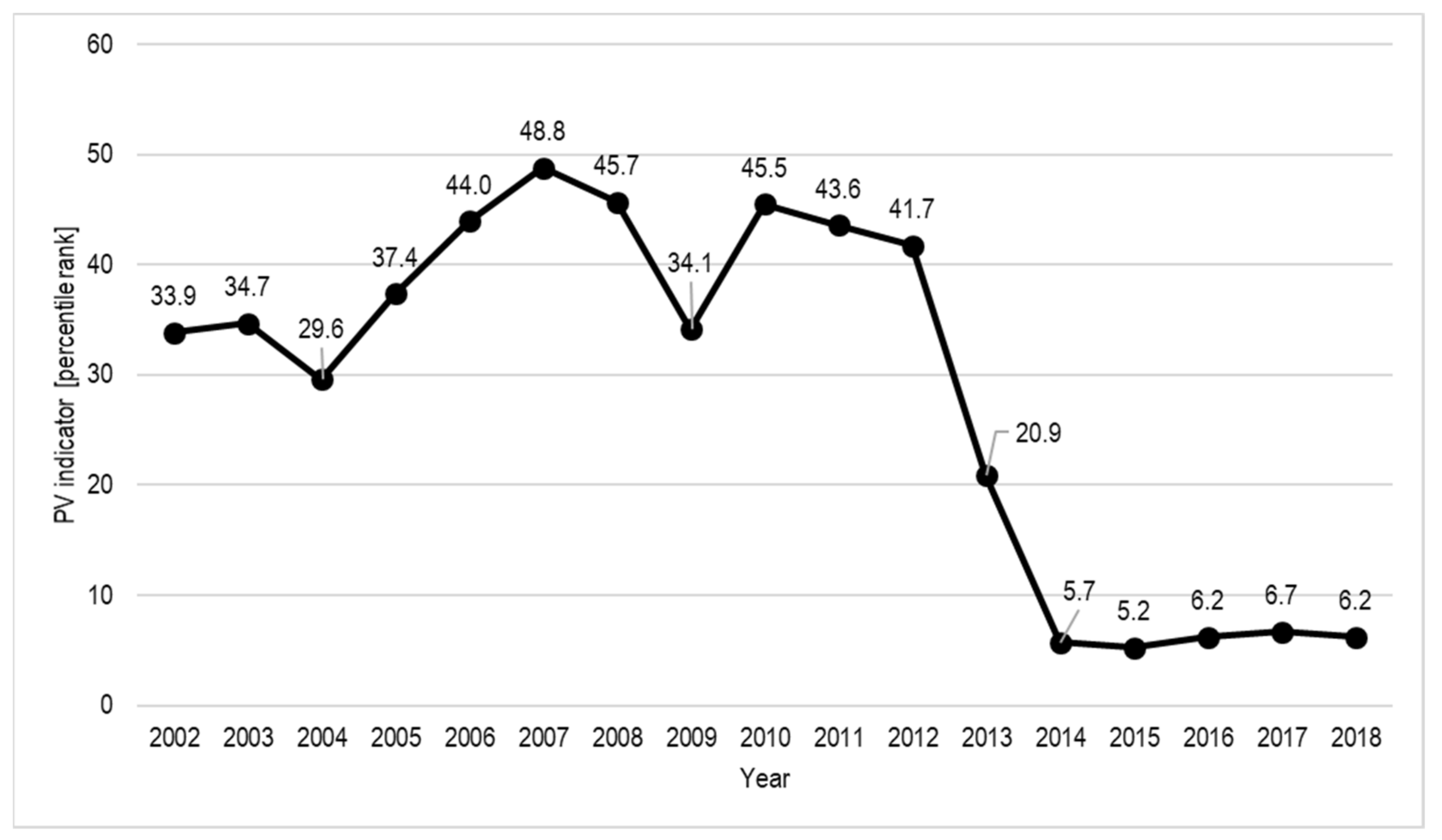

4.1. Impact of Events on Tourism in Ukraine (2000–2019)

4.2. Impact of Political Instability on Tourism in Major Cities—Interview Results

5. Perspectives

- (1)

- the persistence of the present, unstable state of affairs, but with an increase in tourist traffic (10%),

- (2)

- the lack of impact of the political situation on tourism in Ukraine, which remains not highly developed anyway.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boniface, B.G.; Cooper, R.; Cooper, C. Worldwide Destinations: The Geography of Travel and Tourism, 7th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-90181-0. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2019 Edition. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/publication/international-tourism-highlights-2019-edition (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- WTTC. Travel and Tourism Economic Impact 2017. Ukraine; World Travel and Tourism Council: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- WTTC. Travel and Tourism Economic Impact 2017. European Union LCU; World Travel and Tourism Council: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Crotti, R.; Tiffany, M. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017; Paving the Way for a More Sustainable and Inclusive Future; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, S.; Gavrilina, M.; Webster, C.; Ralko, V. Impacts of Political Instability on the Tourism Industry in Ukraine. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2017, 9, 100–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, S.-D.; Gunneriusson, H. Hybrid wars: The 21st-century’s new threats to global peace and security. Sci. Mil. S. Afr. J. Mil. Stud. 2015, 43, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, P.; Kiptenko, V. The geopolitical trial of tourism in modern Ukraine. In Tourism and Geopolitics; Hall, D., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2017; pp. 71–86. ISBN 978-1-78064-761-6. [Google Scholar]

- Global Peace Index. Measuring Peace in a Complex World; Institute for Economics & Peace: Sydney, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, S.; Liu, A. Does Tourism Really Lead to Peace? A Global View. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodorou, A.; Rosselló, J.; Xiao, H. Global Economic Crisis and Tourism: Consequences and Perspectives. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, E. The Impacts of Political and Economic Uncertainties on the Tourism Industry in Turkey. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Afonso-Rodríguez, J.A. Evaluating the Dynamics and Impact of Terrorist Attacks on Tourism and Economic Growth for Turkey. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2017, 9, 56–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso-Rodríguez, J.A.; Santana-Gallego, M. Is Spain Benefiting from the Arab Spring? On the Impact of Terrorism on a Tourist Competitor Country. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1371–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.D.; Campo, S. The Influence of Political Conflicts on Country Image and Intention to Visit: A Study of Israel’s Image. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramov, E.; Abdullayev, A. Effects of political conflict and terrorism on tourism: How crisis has challenged Turkey’s tourism develoment. In Challenges in National and International Economic Policies; Udvari, B., Voszka, É., Eds.; University of Szeged: Szeged, Hungary, 2018; pp. 160–175. ISBN 978-963-315-364-2. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Saad, S.K. Political Instability and Tourism in Egypt: Exploring Survivors’ Attitudes after Downsizing. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2017, 9, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, O.S.; Neubauer-Shani, M. Does International Tourism Affect Transnational Terrorism? J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekar, S.; Patri, R.; Narayanan, B. International Tourist Arrival in India. Foreign Trade Rev. 2018, 53, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuto, B.K.; Groves, J.L. The Effect of Terrorism: Evaluating Kenya’s Tourism Crisis. e Rev. Tour. Res. 2004, 2, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Selmi, N. Tunisian Tourism: At the Eye of an Arab Spring Storm. In Tourism in the Arab World: An Industry Perspective; Almuhrzi, H., Alriyami, H., Scott, N., Eds.; Channel View: Bristol, UK, 2017; pp. 145–160. ISBN 978-1845416140. [Google Scholar]

- Samitas, A.; Asteriou, D.; Polyzos, S.; Kenourgios, D. Terrorist Incidents and Tourism Demand: Evidence from Greece. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhoun, D.R.M.; Masa’deh, D.R.; Al-Lozi, P.M. The Impact of the September 11th and Amman Hotel Explosion Incidents: The Case on the Incoming Tourism in Jordan. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbet, S.; O’Connell, J.F.; Efthymiou, M.; Guiomard, C.; Lucey, B. The Impact of Terrorism on European Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakos, K.; Kutan, A.M. Regional Effects of Terrorism on Tourism in Three Mediterranean Countries. J. Confl. Resolut. 2003, 47, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Saboori, B.; Khoshkam, M. Does Security Matter in Tourism Demand? Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Stavrinoudis, T.A. Impacts of the Refugee Crisis on the Hotel Industry: Evidence from Four Greek Islands. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikšić Radić, M. Terrorism as a Determinant of Attracting FDI in Tourism: Panel Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araña, J.E.; León, C.J. The Impact of Terrorism on Tourism Demand. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrevska, B. Predicting Tourism Demand by A.R.I.M.A. Models. Econ. Res. Istraz. 2017, 30, 939–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J.; Connell, J. Tourism: A Modern Synthesis, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1408088432. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, W.J. The Effect of Terrorism on Executives’ Willingness to Travel Internationally. The City University of New York, New York, NY, USA, 1990. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Sönmez, S.F. Tourism, Terrorism, and Political Instability. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 416–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; O’Sullivan, V. Tourism, political stability and violence. In Tourism, Crime and International Security Issues; Pizam, A., Mansfeld, Y., Eds.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 105–121. ISBN 978-0471961079. [Google Scholar]

- Wahab, S.; Cooper, C. (Eds.) Tourism in the Age of Globalisation; Routledge: London, UK, 2001; ISBN 978-0415758185. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.S. Textbook on Criminology, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-0-19-959270-8. [Google Scholar]

- Helmy, E.M. Political Uncertainty: Challenges to Egyptian tourism policy. In Tourism as an Instrument for Development: A Theoretical and Practical Study. Bridging Tourism Theory and Practice; Fayos-Solà, E., Alvarez, M.D., Cooper, C., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; Volume 5, pp. 301–315. ISBN 978-0-85724-679-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Crisis Events in Tourism: Subjects of Crisis in Tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamarneh, A.; Steiner, C. Islamic Tourism: Rethinking the Strategies of Tourism Development in the Arab World After September 11, 2001. Comp. Stud. South Asia Afr. Middle East 2004, 24, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Crotts, J.C.; Law, R. The Impact of the Perception of Risk on International Travellers. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2007, 9, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, G.; Saha, S. Do Political Instability, Terrorism, and Corruption Have Deterring Effects on Tourism Development Even in the Presence of Unesco Heritage? A Cross-Country Panel Estimate. Tour. Anal. 2013, 18, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causevic, S.; Lynch, P. Political (in)Stability and Its Influence on Tourism Development. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, B. Towards a Framework for Tourism Disaster Management. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorca-Vivero, R. Terrorism and international tourism: New evidence. Def. Peace Econ. 2008, 19, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, Y.; Pizam, A. Tourism, terrorism, and civil unrest issues. In Tourism, Security and Safety: From Theory to Practice; Mansfeld, Y., Pizam, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-7506-7898-8. [Google Scholar]

- Neumayer, E. The Impact of Political Violence on Tourism. J. Confl. Resolut. 2004, 48, 259–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Yap, G. The Moderation Effects of Political Instability and Terrorism on Tourism Development. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Gallego, M.; Rosselló-Nadal, J.; Fourie, J. The Effects of Terrorism, Crime and Corruption on Tourism. Econ. Res. S. Afr. 2016, 595, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Acar, A.; Atsiz, O. Turizm, Terörizm ve Siyasi İstikrarsızlık. Anatolia Tur. Araştırmaları Derg. 2017, 28, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morakabati, Y. Tourism in the Middle East: Conflicts, Crises and Economic Diversification, Some Critical Issues. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranga, M.; Pradhan, P. Terrorism Terrorizes Tourism: Indian Tourism Effacing Myths? Int. J. Saf. Secur. Tour. 2014, 1, 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Pratt, S. Tourism’s Vulnerability and Resilience to Terrorism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coshall, J.T. The Threat of Terrorism as an Intervention on International Travel Flows. J. Travel Res. 2003, 42, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, C.E. Tourism and Terrorism: A Worldwide Perspective. CES Work. Pap. 2016, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, T. Urban Beaches, Virtual Worlds and ‘The End of Tourism’. Mobilities 2009, 4, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.; Ahmad, Z.; Khan, A.A. Dynamic Relationships between Tourist Arrivals, Immigrants, and Crimes in the United States. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korstanje, M.E. The Rise of Thana-Capitalism and Tourism; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-20926-8. [Google Scholar]

- Korstanje, M.E. Terrorism, Tourism and the End of Hospitality in the’ West; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-52251-7. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, R.K.; Ashworth, G.J. Moving from Pilgrimage to “Dark” Tourism: Leveraging Tourism in Palestine. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2011, 11, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabić, M.; Mikulić, I.; Novak, I. Framing research at the tourism and terrorism nexus. Acta Tur. 2017, 29, 181–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.; Idzhylova, K.; Webster, C. Impacts of the Entry of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea into the Russian Federation on Its Tourism Industry: An Exploratory Study. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.; Ivanov, S.H.; Gavrilina, M.; Idzhylova, K.; Sypchenko, L. Hotel Industry’s Reactions to the Crimea Crisis. e Rev. Tour. Res. 2017, 4, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.; Lockyer, T.; Zhang, H. Destination Image and Perceived Risk of Visiting Ukraine: An Exploratory Study of Chinese Male Outbound Tourists. Int. J. Res. Tour. Hosp. 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botterill, D.; Platenkamp, V. Key Concepts in Tourism Research; Sage: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-84860-174-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, F.J., Jr. Survey Research Methods, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kiptenko, V.; Lyubitseva, O.; Malska, M.; Rutynskiy, M.; Zan’ko, Y.; Zinko, J. Geography of Tourism of Ukraine. In The Geography of Tourism of Central and Eastern European Countries; Widawski, K., Wyrzykowski, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 509–551. [Google Scholar]

- Acar, A.; Çetin, G. Economic relationship between terrorism and tourism. J. Recreat. Tour. Res. 2017, 4, 255–274. [Google Scholar]

- STTU. State Statistics Service of Ukraine Website (Derzhavna Sluzhba Statistiki Ukrayiny). Available online: http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- MTRRC. Statistical Data (Statisticheskiye Dannyye). Ministry of Tourism and Resorts of the Republic of Crimea (Ministerstvo Kurortov i Turizma Respubliki Krym). Available online: http://mtur.rk.gov.ru/rus/info.php?id=608306 (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Kиpильчуk, C.; Kirilchuk, S.; Haлиbaйчehko, E.; Nalivaychenko, E. Development of tourism and recreational complex of crimea. Serv. Russ. Abroad 2017, 11, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Webster, C.; Ivanov, S. Political Ideologies as Shapers of Future Tourism Development. J. Tour. Futur. 2016, 2, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirini-Popławski, Ł. Genoese Fortress in Sudak (Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Ukraine) and its tourist use (Genueńska twierdza w Sudaku (Autonomiczna Republika Krymu, Ukraina) i jej turystyczne wykorzystanie). In Polonia Italia Mediterraneum: Studies in Honor of Prof. Danuta Quirini-Popławska (Polonia-Italia-Mediterraneum. Studia Ofiarowane Pani Prof. dr hab. Danucie Quirini-Popławskiej); Burkiewicz, Ł., Hryszko, R., Mruk, W., Wróbel, P., Eds.; Uniwersytet Jagielloński: Kraków, Poland, 2018; pp. 435–450. ISBN 978-83-65080-80-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rutynskyi, M.; Kushniruk, H. The Impact of Quarantine Due to COVID-19 Pandemic on the Tourism Industry in Lviv (Ukraine). Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2020, 18, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinchenko, V.; Dubchak, Y. Problems of the Force Majeure Circumstances Impact on the Hospitality Industry (on the Example of the COVID-19 Pandemic)). Bull. Kyiv Natl. Univ. Cult. Arts. Ser. Tour. 2020, 3, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNTWO Tourism Highlights, 2002 Edition. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284406876 (accessed on 5 September 2017).

- UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2005 Edition. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284411900 (accessed on 12 October 2017).

- UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2008 Edition. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284413560 (accessed on 5 September 2017).

- UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2012 Edition. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284414666 (accessed on 5 September 2017).

- UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2016 Edition. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284418145 (accessed on 5 September 2017).

- UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2017 Edition. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419029 (accessed on 5 September 2017).

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.; Mastruzzi, M. The Worldwide Governance Indicators: Methodology and Analytical Issues. Hague J. Rule Law 2011, 3, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WGI. Statistics of Political Stability and Absence of Violence. Worldwide Governance Indicators. Available online: www.govindicators.org (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Collective Means of Accommodation in Ukraine in 2013, Statistical Bulletin (Kolektivni Zasobi Rozmishhuvannia v Ukraini u 2013 Roci, Statistichnij Bjuleten’). Available online: http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua (accessed on 20 October 2017).

- Collective Means of Accommodation in Ukraine in 2014, Statistical Bulletin (Kolektivni Zasobi Rozmishhuvannia v Ukraini u 2014 Roci, Statistichnij Bjuleten’). Available online: http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/Arhiv_u/15/Arch_kzr_bl.htm (accessed on 20 October 2017).

- Collective Means of Accommodation in Ukraine in 2015, Statistical bulletin (Kolektivni Zasobi Rozmishhuvannia v Ukraini u 2015 Roci, Statistichnij Bjuleten’). Available online: http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/Arhiv_u/15/Arch_kzr_bl.htm (accessed on 20 October 2017).

- Collective Means of Accommodation in Ukraine in 2016, Statistical Bulletin (Kolektivni Zasobi Rozmishhuvannia v Ukraini u 2016 Roci, Statistichnij Bjuleten’). Available online: http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/Arhiv_u/15/Arch_kzr_bl.htm (accessed on 20 October 2017).

- Kulendran, N.; Shan, J. Forecasting China’s Monthly Inbound Travel Demand. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 13, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelagatti, M.M. Time Series Modelling with Unobserved Components; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781482225013. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, C.; Witt, S.; Wilson, N. An Intervention of the Time Series Behavior of International Tourist Arrivals. Tour. Econ. 1994, 21, 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Publichnyj Zvit. Upravlinnja Turyzmu Ta LKP. Centr Rozvytku Turyzmu m. L’vova. Available online: https://city-adm.lviv.ua/public-information/offices/upravlinnia-turyzmu/zvity/12953/download?cf_id=36 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Kosheleva, A. I (Tourist and Recreational Complex of Crimea: Problems and Prospects of Development in the Transition Period). Reg. Ekon. Sotsiologiya (Region Econ. Sociol.) 2015, 3, 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, D.A.; Popov, L.A. Problemy i Perspektivy Turizma v Krymu (Challenges and Prospects of Tourism in the Crimea). Vestn. Ross. Ekono Micheskogo Univ. Im. G.V. Plekhanova (Bull. Plekhanov Russ. Univ. Econ.) 2014, 6, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchmaeva, O.V.; Mahova, O.A. The development of tourism sector in the Republic of Crimea: Problems and assessment. Stat. Econ. 2015, 6, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Podkorytova, E.; Grzhebina, L.; Romanenkov, A.; Andropova, E.; Kutin, I. Wellness Tourism in Crimea: Analysis of Development Problems and Prospects. Serv. Russ. Abroad 2016, 10, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, G. The Crimea Question: Identity, Transition, and Conflict; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781932650013. [Google Scholar]

- Berryman, J. Crimea: Geopolitics and tourism. In Tourism and Geopolitics; Issues and Concepts from Central and Eastern Europe; Hall, D., Ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2017; pp. 57–70. ISBN 978-1-78064-761-6. [Google Scholar]

- Programma Razvitija Kurortov i Turizma v Respublike Krym Na 2015-2017 Gody. Postanovleniju Soveta Ministrov Respubliki Krym Ot 09 Dekabrja 2014 Goda № 501 (State resort development program and tourism in the republic of Crimea in the years 2015-2017. In Decision of the Council of Ministers Republic of Crimea dated 9 December, 2014 No. 501). Available online: http://www.rk.gov.ru/rus/file/pub/pub_284395.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2017).

- Vyazovik, S.M. Sostojanie i Perspektivy Razvitija Turistskoj Otrasli Kak Bjudzhetoobrazujushhej v Respublike Krym (Current State and Development of the Tourist Industry as a Budget-Funding Project in Autonomous Republic of Crimea). Vestn. Astrakhan State Tech. Univ. Ser. Econ. 2017, 3, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riashchenko, V.; Zivitere, M.; Kutyrieva, L. The Problems of Development of the Ukrainian Tourist Market and Ways of Their Solutions. Inf. Technol. Manag. Soc. 2015, 8, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, F.; Holdschlag, A.; Ahmad, B.; Qadir, I. War, Terror and Tourism: Impact of Violent Events on International Tourism in Chitral, Pakistan. Tourism 2011, 59, 465–479. [Google Scholar]

- Rittichainuwat, B.N.; Chakraborty, G. Perceived Travel Risks Regarding Terrorism and Disease: The Case of Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Determining Future Travel Behavior from Past Travel Experience and Perceptions of Risk and Safety. J. Travel Res. 1998, 37, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buigut, S.; Braendle, U.; Sajeewani, D. Terrorism and Travel Advisory Effects on International Tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moufakkir, O.; Kelly, I. (Eds.) Tourism, Progress and Peace; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84593-677-8. [Google Scholar]

- Becken, S.; Carmignani, F. Does Tourism Lead to Peace? Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 61, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, L. Tourism—The World’s Peace Industry. J. Travel Res. 1988, 27, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, L. Peace through Tourism: The Birthing of a New Socio-Economic Order. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, I.A.; Altinay, L. Impacts of Political Instability on Tourism Planning and Development: The Case of Lebanon. Tour. Econ. 2006, 12, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alluri, R.M.; Leicher, M.; Palme, K.; Joras, U. Understanding Economic Effects of Violent Conflicts on Tourism: Empirical Reflections from Croatia, Rwanda and Sri Lanka. In International Handbook on Tourism and Peace; Wohlmuther, C., Wintersteiner, W., Eds.; Drava Verlag/Zalozba Drava: Klagenfurt, Austria, 2014; pp. 101–119. ISBN 978-3-85435-713-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J.; Morakabati, Y. Tourism Activity, Terrorism and Political Instability within the Commonwealth: The Cases of Fiji and Kenya. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.; Ivanov, S.H. Tourism as a force for political stability. In International Handbook on Tourism and Peace; Wohlmuther, C., Wintersteiner, W., Eds.; Drava Verlag/Zalozba Drava: Klagenfurt, Austria, 2014; pp. 167–180. ISBN 978-3-85435-713-1. [Google Scholar]

- ETC. European Tourism amid the Crimea Crisis (Report); European Travel Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fermani, A.; Sergi, M.R.; Carrieri, A.; Crespi, I.; Picconi, L.; Saggino, A. Sustainable Tourism and Facilities Preferences: The Sustainable Tourist Stay Scale (STSS) Validation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, M.; Niedziółka, A.; Krasnodębski, A. Respondents’ Involvement in Tourist Activities at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, Tourism and Global Change: A Rapid Assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, Transformations and Tourism: Be Careful What You Wish For. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Respondent | Total |

|---|---|

| Hotel manager | 17 |

| Department of tourism in government administration | 14 |

| Heads of tourism departments at state-run universities | 34 |

| Total | 65 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tomczewska-Popowycz, N.; Quirini-Popławski, Ł. Political Instability Equals the Collapse of Tourism in Ukraine? Sustainability 2021, 13, 4126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084126

Tomczewska-Popowycz N, Quirini-Popławski Ł. Political Instability Equals the Collapse of Tourism in Ukraine? Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084126

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomczewska-Popowycz, Natalia, and Łukasz Quirini-Popławski. 2021. "Political Instability Equals the Collapse of Tourism in Ukraine?" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084126

APA StyleTomczewska-Popowycz, N., & Quirini-Popławski, Ł. (2021). Political Instability Equals the Collapse of Tourism in Ukraine? Sustainability, 13(8), 4126. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084126