1. Introduction

From the point of view of many authors [

1,

2,

3,

4], effective corporate marketing communication is one of the foundations of market success. When the number of communication messages exceeds the capacity for their processing by target markets, rationalization and effective targeting is the key to the ultimate survival of both the communicated message and the subject itself [

5]. Due to evolutionary changes in consumer behavior, an increasing degree of interaction is shifting to the digital environment [

6,

7]. Both the demand and supply sides of the market respond to these evolutionary changes with activities aimed at maximizing their benefits. Customers benefit from greater transparency and possibilities of wider choices, while companies benefit from market expansion and partial optimization of their fixed costs. However, there are several business risks, such as reputational risks, which are associated with the transition from offline to online. We agree with the authors of [

8,

9,

10,

11], who claim that customers are not a homogeneous group, and their preferences and degree of acceptance of innovations vary considerably across the market. When the dominant part of business transactions is still offline, and marketing communication is hybrid, some customers are targeted inefficiently. We are starting our research from the assumption that different economically active customer groups approach the adoption of marketing communication (in our case, marketing communication on social media) in a diverse way. As a significant proportion of customers does not distinguish between communications on social networks according to their nature [

12,

13], some business entities use this alleged ignorance of the customer for short-term profit. On the other hand, some customers strictly distinguish the nature of communications on social networks. As we can see in the works of selected authors [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], in both cases, incorrect (or irresponsible) targeting can lead to a reputational risk. In the first case, it is the targeted behavior of the business entity, i.e., the reputational risk arises mainly from the customer’s post-purchase cognitive dissonance. In this case, a dissatisfied customer poses a foreseeable and, in some points of view, acceptable risk for a company. In the second case, over-targeted e-marketing activity can be seen as a breach of privacy, which can lead to serious mistrust. This can ultimately result in the loss of the customer. In our opinion, it is necessary to examine the extent to which it is acceptable for different groups of users to be the addressee of marketing communication activities within virtual social networks. The presented study is part of comprehensive research on the advancement of economic and social innovation through the creation of an environment enabling business succession. In the form of quantitative empirical analysis, we examine the positive acceptance of marketing on social networks among seven predefined customer groups (divided according to their types of economic activity). Before proceeding to the presentation of the results and discussion of the findings, we will summarize the current state of knowledge on the researched issues.

2. Theoretical Framework

In the following subsections, we will approach the state of knowledge on selected parts of the issue of marketing management, specifically marketing management in the environment of virtual social media. In the form of the decomposition of key concepts, we will focus on the fundamentals of the topic. As the presented study has the character of basic research, we are predominantly interested in the works of authors who in recent decades have contributed to the shift of knowledge in the field in the context of the Central European market.

2.1. E-Marketing—Transition from Offline to Online

From the point of view of the fundamentals of the analyzed issue, we start from the claims of authors Stuchlík and Dvořáček [

20], who define the e-marketing mix as the fusion of the tools of the classic marketing mix with the tools of the Internet. Although it has been more than two decades since its publication, the statements contained in their work are still up to date. Among other things, the statement emphasizes the target groups for which both the marketing and e-marketing mix of the organization are created. In the chapter dedicated to e-marketing [

21], we followed the work of Stuchlík and Dvořáček within the application of Booms and Bitner’s [

22] marketing mix of the “7Ps”. In the Internet environment, the 7Ps of e-marketing can be interpreted as follows in

Table 1:

Based on the basic definitions, we gradually move on to the issue of promotion itself. From the point of view of marketing communication in the Internet environment, we encounter a relatively extensive knowledge apparatus [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. We also come across a relatively ambiguous terminology in distinguishing the conceptual apparatus of the issues of Internet marketing and the issues of Internet promotion. This fact only reflects the state that we record across the issue of traditional marketing management. It arises from the dominant application nature of the issue and the relatively large representation of practitioners as authors across the available literature. In the literature, we often come across the confusion of the terms marketing and promotion, as well as the confusion of the terms promotion and advertising. In our opinion, it is not possible to remove the conceptual ambiguity. For the purposes of further research and to avoid further conceptual ambiguity, we will base our work on the traditional Booms and Bitner [

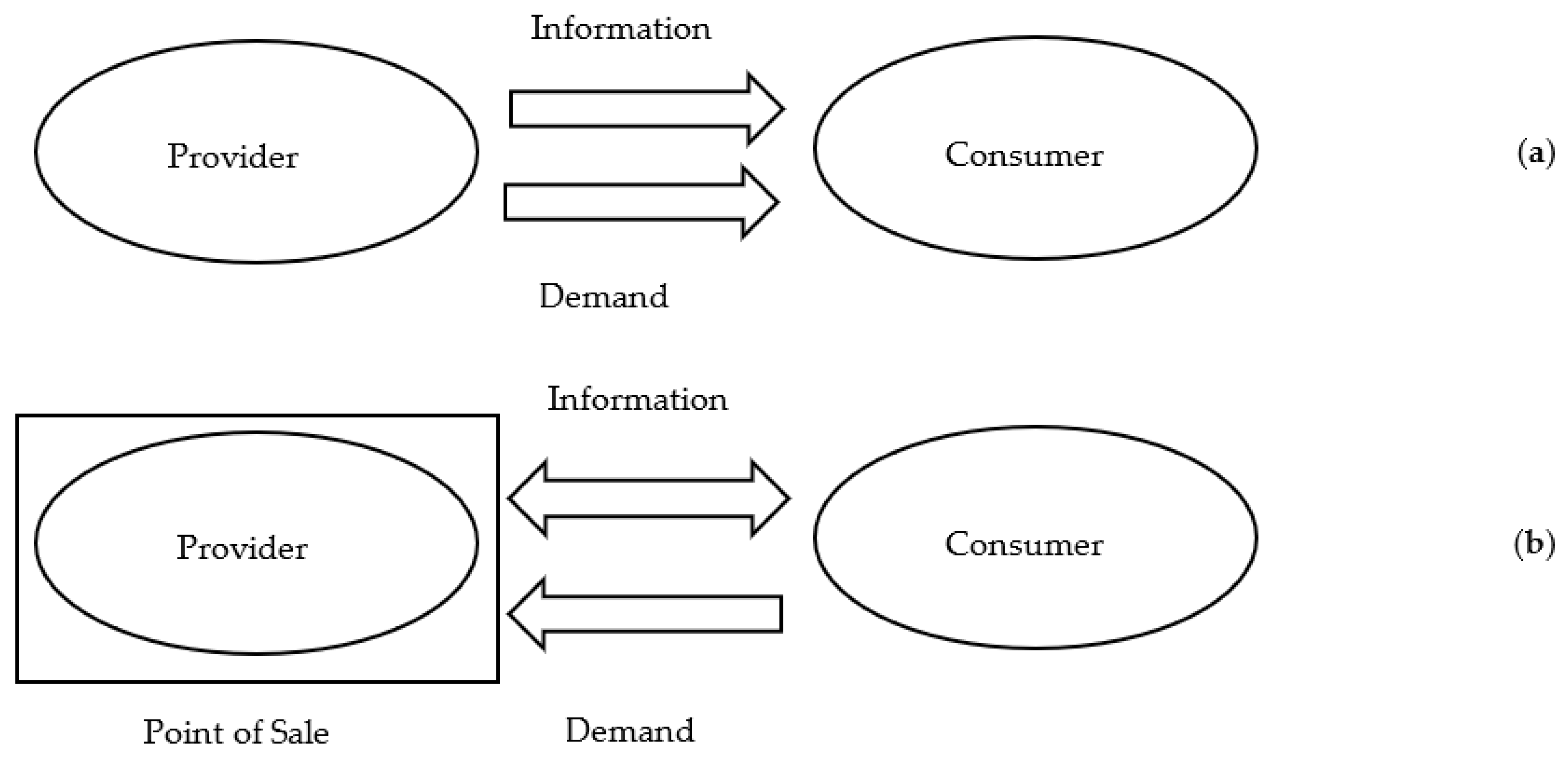

22] marketing mix, where we limit e-marketing only to its applications within the tools of promotion. From the point of view of specifics, we also consider it important to mention the significant difference between marketing communication on the Internet and marketing communication in traditional media. This specifically takes a form in which the message from its provider reaches the consumer. Traditionally (as shown in

Figure 1, part a), a system of pressure (PUSH) is applied in the media, where a message or, more precisely, promotional message is pushed to the target market. Demand is conditioned by pressure. On the Internet, this process revolves (as shown in

Figure 1 part b) and a traction system (PULL) is created. The customer him/herself actively searches for information; the demand is conditioned by pulling and interactions and often arises directly at the point of sale.

A specific form of communication, business entity to customer entity (B2C), generates a significant number of benefits for the involved entities [

28,

29]. The main advantage for both parties is precise targeting, addressed communication and, last but not least, active feedback. Under ideal circumstances of full market transparency and rationality on both the demand and supply sides, this is the optimal transaction model. However, given the real nature of the market, we encounter a relatively high level of irrationality on both sides [

30,

31]. While both the demand and supply side are motivated in a diverse way, the goals and methods are also diverse. Market transparency determined by the openness of the Internet as a communication medium, combined with the ability to generate active feedback, becomes a reputational risk generator for a large part of the market [

32]. It is therefore necessary to approach the creation of a communication mix with the necessary dose of precision. From our point of view, this level of precision is achievable only by continuous research into the issue. By approaching the fundamentals of the topic, we move fluently into the issue of marketing in the social media environment.

2.2. Social Media Marketing—New Standard for Promotion

As the main purpose of social media is to create communities, the Internet has become a meeting place for 21st century socialization (especially at the time of the closure of economies related to the COVID-19 pandemic). From the relatively simple virtual chat rooms of the late 1990s, the interactions of participants under the pressure of increasingly advanced technologies are moving to a sophisticated online space that is able to partially saturate the social needs of its users. Organizations take full advantage of the opportunities that social networks provide them [

33]. We consider this to be the key to our further research. We also fully agree with the statements of Nadaraja and Yazdanifad [

34] who in their study claimed that in recent years, social media has become ubiquitous and most important for social networking, content sharing and online access. Due to its reliability, consistency and instantaneous features, social media opens a wide place for businesses, such as online marketing. Deepika and Srinivasan [

35] complements the statement with a definition that social media marketing uses social media platforms and websites to promote product and services, as marketers are always in search of media that improve their targeted marketing efforts. According Wibowo et al. [

36], social media has been playing an important role in the marketing strategy of businesses. The rate of adoption of this kind of communication is appropriate in general [

37]. As a part of social media, social networking sites can be utilized by enterprises to create direct communication and good relationships with their customers. Therefore, enterprises using social networking sites have to select the right marketing content to enhance strong customer relationships, which leads to their behavior generating sustainable performance for enterprises. However, it is not just a domain of corporations, we also encounter the issue of mastering the tools of social media marketing in smaller business units. As far as individual companies are concerned, in the case of private praxis of medical doctors, the professional literature has been presenting us for almost a decade with partial results of studies [

38] in which social media marketing is described as a growing trend that will have significant potential in the future. Entrepreneurs in the field of agriculture are also discovering the field of social media marketing. In the study of Nawi, Baharudin and Baharudin [

39] the authors describe the concerns that entrepreneurs are confronted with in terms of the effectiveness of this type of marketing communication, compared to traditional forms of promotion. Different levels of acceptance of social media marketing across generations and across specific media are proving to be a key point of effectiveness. With regard to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), it is necessary to mention another important factor that determines possible success in terms of adopting innovative forms of communication. In the literature review on the adoption of social media marketing by SMEs, the authors Dahnil, Marzuki, Langgat and Fabeil [

40] identified, among other things, the cultural factor, which to some extent determines the success of the offline–online transition process.

At this point, we get to the core of the issue, where we fully identify with the work of Groothuis, Spil and Effing [

41], who claimed that social media marketing is becoming an increasingly important tool for companies to influence consumer decision making. However, there is currently little empirical knowledge about the extent of the influence of this form of marketing on the decision-making process of consumers [

42,

43,

44,

45]. Our research has the ambition to contribute to a better understanding of the issue through the interpretation of selected factors that have been identified based on empirical results.

3. Materials and Methods

This part of the study is focused on defining its main goal. After its definition, the study continues by describing the research question as a starting point for formulating statistical hypotheses. Subsequently, in this section, we describe the matter of the work, as well as methods of obtaining and processing primary information. At the end of the section, we clearly describe the proposed methods of solving the research problem, primarily in the form of statistical analyses.

Based on the knowledge accumulated during the examination of the theoretical basis of the subject, we formulated the main goal of the present study. Specifically, we aim to examine the attitudes of customers in terms of their adoption of innovative forms of promotion in the environment of social media.

Given the aim of the study, we consider it necessary to clarify the following research question, namely: Does a specific form of economic activity of customers influence their attitudes towards the adoption of social media marketing carried out by companies for the purpose of their promotion?

The first step in the statistical analysis is the correct formulation of the null

H0 or alternative

H1 hypothesis. The hypothesis

H0 is a statement that usually declares no difference or dependence between variables. The alternative hypothesis

H1 means a situation where the null hypothesis does not apply. It is usually expressed as the existence of a dependency between variables. In relation to the specified research problem, the following statistical hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 0 (H0): The type of economic status of the customer is not related to how the customer perceives the use of virtual social networks by companies for promotional purposes.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The perception of the use of social networks for the purpose of corporate promotion is related to the type of economic position of the customer.

The subject of the research involves companies operating in the Central European market. At the same time, the subject of the research is their customers, represented by a database of registered users of the selected internet portal. From the customer’s point of view, the research set takes the form of the entire population of Central Europeans. The research sample consists of randomly selected respondents from the research set of 5000 respondents (of which 1584 actively participated).

For the following analysis, seven customer groups were also predefined based on their economic activity/economic status, namely:

As a part of the solution of the research problem, analysis and synthesis are used as primary scientific methods. Other scientific methods used in solving a research problem included the methods of induction and deduction, the method of comparison, the method of abstraction and, last but not least, selected methods of mathematical statistics.

The primary information source for the research is provided through a questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of sixteen questions. The first five questions are focused on the placement of the respondent within individual segments. The following eleven questions are focused on identifying their activity in the virtual environment, identifying ways of obtaining information, their attitudes to innovative forms of marketing communication and, last but not least, their attitudes to e-marketing forms in its various forms. The questions in the questionnaire use a wide range of options for marking and choosing options. From fully open, through partially open to closed questions, they give respondents the opportunity to express their views and attitudes as accurately as possible with respect to the examined issues. To ensure the best possible processability of data, Likert five-point scales (from positive to non-positive attitudes) are used in selected questions.

For the purpose of solving the research problem, we use selected mathematical–statistical methods. The data collected in the questionnaire survey are sorted and coded using the MS Office suite and thoroughly statistically analyzed using the STATISTICA program.

From the point of view of specific mathematical and statistical methods, we use, in particular:

Pearson correlation coefficient;

Spearman correlation coefficient;

Kendall correlation coefficient.

As a part of more detailed statistical testing, we will also use the following mathematical–statistical methods, namely:

The last of the used apparatus is cluster analysis, which deals with how statistical units should be classified into groups so that there is as much similarity within groups as possible and as much difference between groups as possible. This type of analysis is used, e.g., in market segmentation, where the classification of consumers is based on a combination of several variables.

When summarizing the data obtained in the research, we also use tables, graphs and histograms for their interpretation.

4. Results and Discussion

Given the aim of the study, we consider it necessary to clarify the following research question: Does a specific form of economic activity of customers influence their attitudes towards the adoption of social media marketing carried out by companies for the purpose of their promotion?

The following statistical hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 0 (H0): The type of economic status of the customer is not related to how the customer perceives the use of virtual social networks by companies for promotional purposes.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The perception of the use of social networks for the purpose of corporate promotion is related to the type of economic position of the customer.

In the independence hypothesis, both variables are considered to be random variables and are therefore randomly selected from the population, assuming their complete independence. This means that the value of Var1 does not affect the conditional distribution of Var2. We chose as variables:

Meanwhile, if the null hypothesis is rejected, then Var2 will be a dependent variable on Var1. We obtained the relevant data from completed questionnaires to a total number of n = 1584. We set the significance level α equal to 0.05.

Since we worked with two numerical cross-tabulated variables, we used a contingency table to determine their relationship. In the statistical program, we created a corresponding contingency table from the data obtained from the questionnaires. To measure the strength of the relationship in the contingency table, several coefficients have been proposed that work similarly to the correlation coefficient. Specifically, these are the values of the Pearson’s chi-square test, the chi-square test of the maximum value and the contingency coefficient resp. Cramer’s coefficient, the calculation of which is based on the chi-square test. This test is valid asymptotic, so we can only use it with a sufficient number of observations. Thus, it is not necessary to verify normality, due to the use of non-parametric testing, but it is necessary that the variables come from a random selection and in a sufficient number, which is fulfilled in our case. The only prerequisite for using the chi-square test (apart from sampling rules) is the rule that the expected frequencies must not be less than

mij ≥ 1. We will check this rule in

Table 2 which displays expected frequencies.

As the expected frequencies are less than 1 in some fields, the condition of using the chi-square test is violated. Given this fact, although Pearson’s chi-square test gives us the tested statistics X2 = 67.718 ≥ 36,41 = X2(24) and p = 0.00003, which is significantly less than our chosen significance level of 0.05, we cannot reject the hypothesis of the independence of variables. If we neglected this rule, the test would confirm the dependence of the given variables, even though it would not actually occur. Thus, we move on to the analysis of the derived table, which is created from the original contingency table by merging the less occupied categories in the individual selections. Subsequently, we will test this combined contingency table and, based on the calculated tests and coefficients, we will decide on the acceptance or rejection of the selected hypotheses.

In

Var1 we have merged the sparsely populated category

6—Retiree with the category

7—Other and we will call the merged category

6—Other. In

Var2 we did not merge any of the categories. In this case, the condition for using the Pearson’s chi-square test is no longer violated and thus the calculated statistics are applicable. We can therefore proceed to the validation of the hypothesis in the following

Table 3:

As we can see in

Table 3, X

2 = 46.05426 ≥ 31,41 = X

2(20) and

p = 0.00079 ≤ 0.05. Thus, at the level of significance chosen by us, we can reject the null

H0 hypothesis and accept the hypothesis of dependence.

This means that we have confirmed the

H1 hypothesis that the perception of the use of social networks for corporate promotions is related to the economic status of the user. If we look in more detail in

Table 4, we find that the perception of the use of social networks by organizations for the purpose of their promotion is related to the economic status of users as follows:

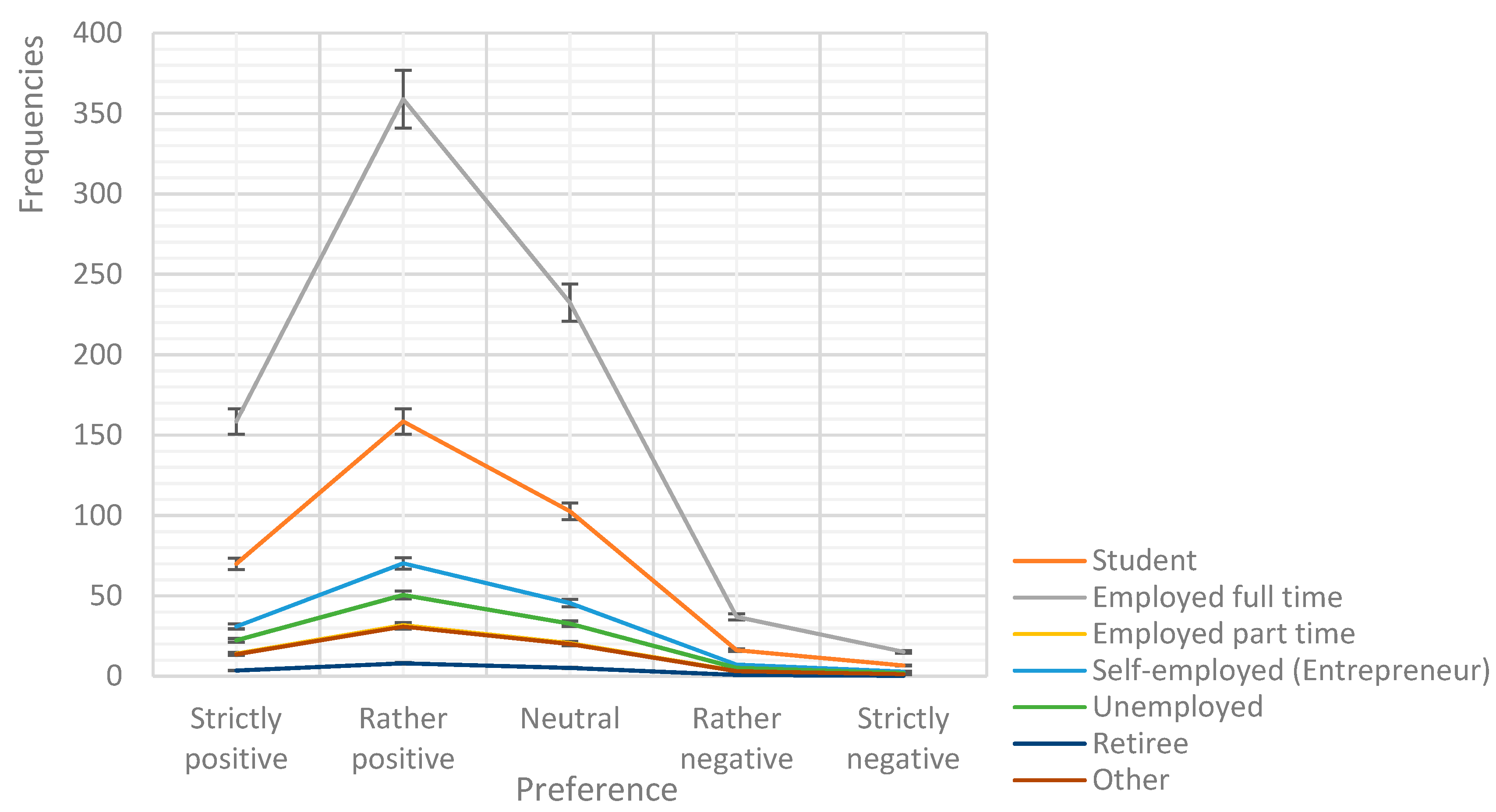

As shown in the following

Figure 2—the graph of interactions, students’ perceptions of the use of social networks are rather positive, while explicitly positive and neutral perceptions are equally represented, and other answers are negligible. Similar, but much more pronounced, interactions were recorded in the responses of full-time employees. In the “other” and part-time employee groups, the perception is rather positive but not as significantly different from the neutral perception. In the entrepreneur group, the first three categories are similarly represented in percentage terms and the others are insignificant. Unemployed people’s perception of the use of social networks ranges from positive to neutral and retirees’ perceptions are exclusively neutral.

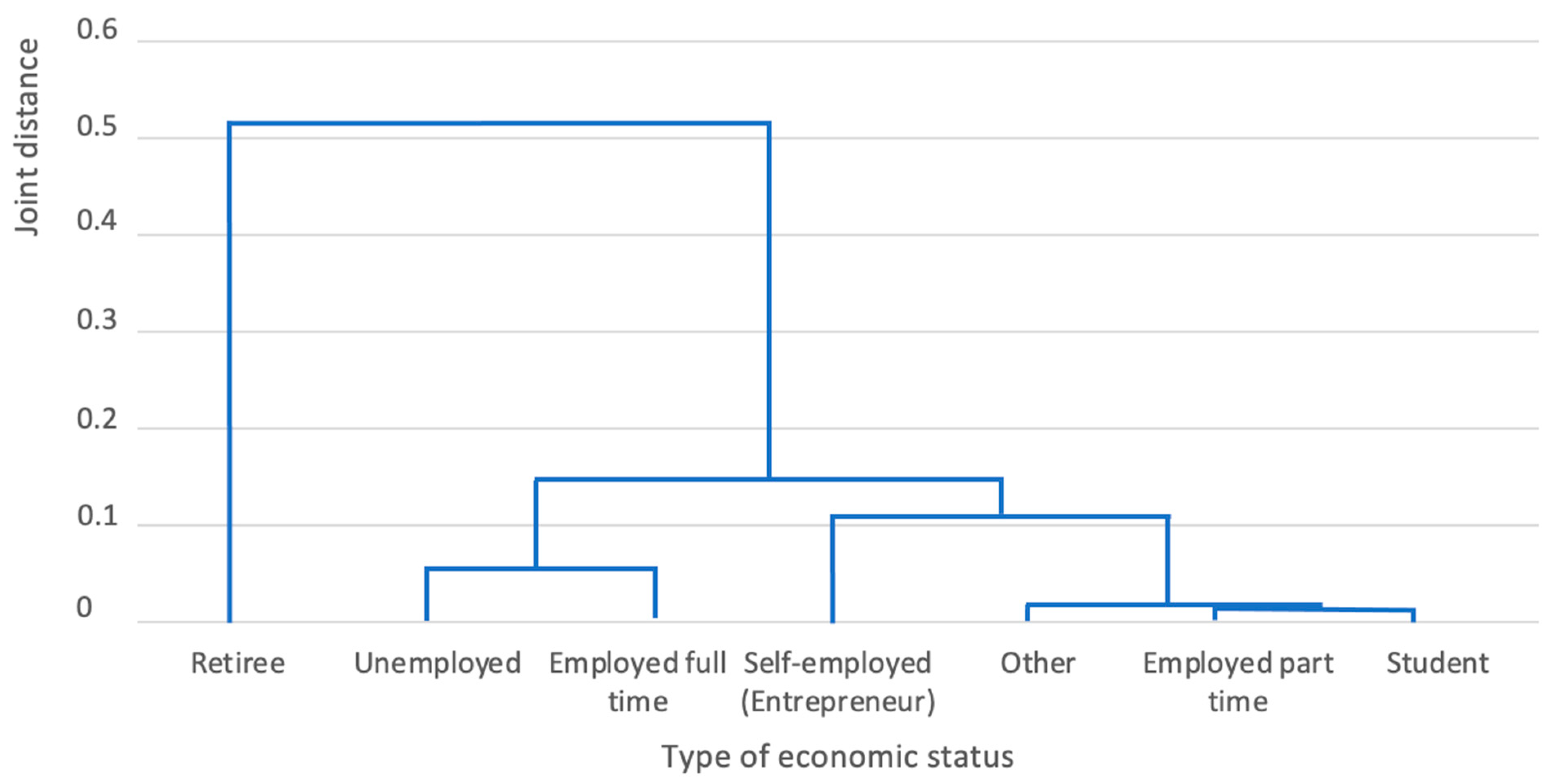

We consider it necessary to profoundly analyze the perception within different economic groups of users. Based on the similarity of the behavior of specific groups, it is possible to more precisely target the online activity with respect to the selected target markets. The results are shown in the following

Figure 3.

As we can see above,

Figure 3 presents the results of the cluster analysis, and the economic status is combined according to how customers perceive the use of social networks by companies. Thus, the

x-axis shows the economic status of users, the

y-axis indicates the degree of dependence on merging. The smaller the connection distance is, the more similar economic groups in perception become. Students and part-time employees perceive the issue the most similarly. It can be seen that their attitude is almost the same. Respondents who were included in the other category have a similar attitude. The unemployed and full-time employees have a very similar view on the issue. Entrepreneurs tend to lean towards the merged other category, students and part-time employees. Retirees are a special category; their perception is relatively far from the perception of all other categories. This may be due to the fact that they do not have much experience or do not use social networks to such an extent as the other groups. As can be seen, the perception of the use of these networks is relatively different from one economic group to another, and it is therefore clear in this case that the rejection of the independence hypothesis was substantiated.

5. Conclusions

Based on a theoretical overview of the literature, it can be stated that the topic is extremely dynamic. However, the foundations of the topic have been unchanged for almost a decade; in the professional literature [

8,

9,

10,

11] we encounter a fundamental statement about the inhomogeneity of consumers in terms of their concentration within the user groups of social media and social networks. From the point of view of inhomogeneity, these are mainly groups of users across different generations. From reference studies [

39], we learn that this factor is not just a local variable, but that it is a global problem that needs to be given due consideration. Another important factor from our point of view is the expectations themselves (and here it must be stated that these are expectations without distinction on the part of both providers and consumers). As a communication medium (due to its acceptance by dominant media players), the Internet has been literally glorified as a modern and universal mass medium [

46]. The same expectations are gradually being transferred to social media, and the works of authors [

38,

41] published in the selected field only confirm the more than decade-long trend of high expectations in terms of the application usability of this communication tool and channel. However, market inhomogeneity, combined with disproportionate expectations, can easily lead to frustration for all stakeholders stemming from failing to meet those expectations. At the same time, these animosities do not necessarily result directly from the technical and technological (i.e., objective) limitations of the medium. The reason for inefficiency may be the fact that the tools of communication policy applied in the social media environment are not sufficiently precise. We considered it necessary to contribute to the shift in knowledge in order to eliminate part of the questions arising from the search for procedures for better targeting of promotional activities of companies. It is possible to argue over the issue of the segmentation of Internet users, and also social media users. In our case, it is segmentation based on economic activity. Customers (users) were divided into seven predefined groups. This segmentation divides customers based on one of the fundamental economic parameters. In the study, we investigated whether the economic status of customers has an impact on their perception (and subsequent adoption) of the use of social networks by organizations for promotional purposes. Statistical testing revealed that the perception of the use of social networks for corporate promotion is related to the type of economic status of the customer. Social media marketing is perceived as rather positive by customers belonging to the categories of students and entrepreneurs, while this form of promotion is evaluated neutrally by customers from the categories of unemployed and retirees. Negative acceptance is recorded only insignificantly across all involved groups. The research also showed that the perception of the use of social networks is relatively different for individual economic groups of customers. We assume that this situation may be due to different perceptions of risk and opportunity across economic groups of customers. However, this is only our assumption, as for the scientific verification of which we did not have enough empirical material. In any case, based on the findings, we can state that the understanding of the similarities of the behavior of customer groups can lead to more precise targeting of the online activity of organizations, thereby increasing their efficiency in spending business resources and eliminating market risks in terms of reputational issues. All of this can contribute to better organizational performance during the transition from offline to online, as well as optimizing processes towards the application of sustainable communication policy tools in business practice.

6. Research Limitations and Direction for Future Research

From the point of view of research limitations, it can be stated that the most significant limitation is the geographical localization of research. The research was carried out on a sample of Central European customers, and the findings arising from it are directed primarily to companies operating in the Central European market. However, as we have no information regarding the fact that the reference markets are characterized by significant differences in consumer behavior and consumer preferences, with a certain degree of abstraction, it is possible to apply the findings globally. However, for confirmed dependences on a global scale, it would be necessary to repeat the research on a representative sample of international customers, or to atomize samples across selected markets.

From the point of view of further research on the issue, we also consider it necessary to examine the supply side of the market, and the specific preferences of business entities in relation to the use of social networks for their promotion. At the same time, both the size of the entity and the business sector prove to be relevant variables with the potential to generate empirical material of significant value.