Social Innovation in Olive Oil Cooperatives: A Case Study in Southern Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Social Innovation in the Context of Cooperativism in Olive Oil

2.2. Context and Case Study

3. Methodology

Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

The Thematic Nature of First Day of Harvest

5. Conclusions

- Enhancing the commercialization of products and fostering the strategy for differentiating and building awareness of the cooperative’s brand, in response to the fragmentation of the olive oil industry;

- Proposing joint solutions with social entrepreneurs that promote the development of the territory;

- Establishing an added value project that helps anchor people to the olive oil producing area;

- Promoting fair trade through payments for the harvest with added value for the farmer.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Somos Digital. Los Centros de Competencias Digitales del Futuro; Junta de Castilla y León, Tecnalia: Valladolid, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://somos-digital.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Los-Centros-de-Competencias-Digitales-del-Futuro.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Mayer, H. Slow innovation in Europe’s peripheral regions: Innovation beyond acceleration. Schlüsselakteure Reg. Welche Perspekt. Bietet Entrep. Ländliche Räume 2020, 51, 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Barquero, A.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C. Local development in a global world: Challenges and opportunities. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2019, 11, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozas Moral, Adoración. Contribución de las Cooperativas Agrarias al Cumplimiento de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Especial Referencia al Sector Oleícola; Centro internacional de investigación e información sobre la economía púbica, social y cooperativa: Ciriec, España, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Martínez, J.D.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Garrido-Almonacid, A.; Gallego-Simón, V.J. Social Innovation in Rural Areas? The Case of Andalusian Olive Oil Co-Operatives. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Cohard, J.C.; Sánchez Martínez, J.D.; Garrido Almonacid, A. Strategic responses of the European olive-growing territories to the challenge of globalization. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2261–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Logroño, P.; Bautista Puig, N. La significación de las cooperativas agrarias en desarrollo del medio rural: El caso de Guissona. In Proceedings of the Coloquio Ibérico de Geografía, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 24–26 October 2012; pp. 1334–1344. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322357515_ in La_significacion_de_las_cooperativas_agrarias_en_el_desarrollo_del_medio_rural_el_caso_de_Guissona (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Montero Aparicio, A. La Economía Social y su Participación en el Desarrollo Rural; Fundación Alternativas: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Puentes Poyatos, R.; Velasco Gámez, M.M. Importancia de las sociedades cooperativas como medio para contribuir al desarrollo económico, social y medioambiental, de forma sostenible y responsable. Revesco 2009, 99, 104–129. [Google Scholar]

- Mozas-Moral, A.; Puente-Poyatos, R. Corporate Social Responsibility and its Parallelism with Cooperative Societies. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2010, 103, 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bastida, M.; Vaquero García, A.; Cancelo Márquez, M.; Olveira Blanco, A. Fostering the SustainableDevelopment Goals from an Ecosystem Conducive to the SE: The Galician’s Case. Sustainability 2020, 12, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Guadaño, J.; Lopez-Millan, M.; Sarria-Pedroza, J. Cooperative entrepreneurship model for sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parras, M.; Torres, F.J.; Mozas, A. El comportamiento comercial del cooperativismo oleícola en la cadena de valor de los aceites de oliva en España. In Metodología y Funcionamiento de la Cadena de Valor Alimentaria: Un Enfoque Pluridisciplinar e Internacional; En Briz, J., De Felipe, I., Eds.; Editorial Agrícola: Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- AICA, Agencia de Información y Control Alimentarios. Available online: https://www.aica.gob.es/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- COI, International Olive Council. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Moral Pajares, E.; Sanchez Martinez, J.D.; Mozas Moral, A.; Bernal Jurado, E.; Medina Viruel, M.J. Local resources and global competitiveness: The exportation of virgin olive oil in andalusia. Boletin de la Asociacion de Geografos Espanoles 2015, 69, 415–435. [Google Scholar]

- Alimarket, Informes y Reportajes de Alimentación. Available online: https://www.alimarket.es/alimentacion/informe/290401/informe-2019-del-sector-de-aceite-de-oliva-en-espana/15/6f8ef4248d67a51b2e8244508ae810e3 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- BEPA. Empowering people, driving change. In Social Innovation in the European Union; European Commission—Bureau of European Policy Advisers (BEPA): Luxembourg, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla, N.; Rojas, A. Una Revisión de las Tendencias en Investigación Sobre la Innovación Social: 1940–2012. Master of Thesis, Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, Bogotá, Colombia, 29 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; Baumann, H.; Ruggles, R.; Sadtler, T.M. Disruptive innovation for social change. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, B. Social innovation: Utopias of innovation from 1830 to the present. In Project on the Intellectual History of Innovation; Working Paper No. 11; INRS: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; Available online: http://www.csiic.ca/PDF/SocialInnovation_2012.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Mulgan, G.; Tucker, S.; Ali, R.; Sanders, B. Social Innovation: What It Is, Why It Matters and How It Can Be Accelerated; The Young Foundation: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; Maccallum, D.; Mehmood, A.; Hamdouch, A. The International Handbook. Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, J.; Tirado, P.; Ariza, A. El Concepto de Innovación Social: Ámbitos, Definiciones y Alcances teóricos. In CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa; 2016; Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/174/17449696006.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Hernández-Ascanio, J. La innovación social como método de investigación participativo y sociopráctico? Tendencias Sociales Revista de Sociología 2020, 6, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiollent, M. Metodologia da Pesquisa-Ação,4ª Edição. São Paulo (SP) in Cortez: Editores Associados. Pesquisa-Ação nas Organizações; Editora Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; Nussbaumer, J. Defining the Social Economy and its Governance at the Neighbourhood Level: A Methodological Reflection. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2071–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcy, R.T.; Mumford, M.D. Social innovation: Enhancing creative performance through causal analysis. Creat. Res. J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.; Monzón, J.L. La economía social ante los paradigmas económicos emergentes: Innovación social, economía colaborativa, economía circular, responsabilidad social empresarial, economía del bien común, empresa social y economía solidaria. CIRIEC-España Revista de Economía Pública Social y Cooperativa 2018, 93, 5–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/Eurostat. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting, Reporting and Using Data on Innovation, 4th ed.; The Measurement of Scientific, Technological and Innovation Activities; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Asongu, J.J. Innovation as an argument of CSR. J. Bus. Public Policies 2007, 1, 178–214. [Google Scholar]

- Young, D.R.; Searing, E.A.; Brewer, C.V. (Eds.) The Social Enterprise Zoo; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dees, J.G. The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship, The Social Entrepreneurship Fundersworking Group. 1998. Available online: https://centers.fuqua.duke.edu/case/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/03/Article_Dees_MeaningofSocialEntrepreneurship_2001.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Leick, B. Institutional entrepreneurs as change agents in rural-peripheral regions? ISR-Forsch. 2020, 49, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mozas, A.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C. La Economía Social: Agente de cambio estructural en el ámbito rural. Rev. Desarro. Rural Coop. Agrar. 2000, 4, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, P.H. Democratizing rural economy: Institutional friction, sustainable struggle and the cooperative movement. Rural. Sociol. 2004, 69, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pérez González, M.C.; Jiménez García, M. Dinámica Territorial y Economía Social: Una Reflexión con Especial Referencia a Andalucía Ante los Cambios Sociales. Revista De Estudios Empresariales. Segunda Época, (1). Recuperado a partir de. 2012. Available online: https://150.214.170.182/index.php/REE/article/view/650 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Baselice, A.; Prosperi, M.; Marini Govigli, V.; Lopolito, A. Application of a Comprehensive Methodology for the Evaluation of Social Innovations in Rural Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Alonso, D. Investigación Artística e Innovación Social: Herramientas Para la Transferencia del Conocimiento Científico. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, R. A/r/tography. Rendering Self Through Arts-Based Living Inquiry; Pacific Educational Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Arte, Líquido? Sequitur: Madrid, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kristoffersen, E.; Blomsma, F.; Mikalef, P.; Li, J. The smart circular economy: A digital-enabled circular strategies framework for manufacturing companies. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastón, A.; Blázquez-Cabrera, S.; Garrote, G.; Mateo-Sánchez, M.C.; Beier, P.; Simón, M.A.; Saura, S. Response to agriculture by a woodland species depends on cover type and behavioural state: Insights from resident and dispersing Iberian lynx. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrote, G.; López, G.; Bueno, J.F.; Ruiz, M.; de Lillo, S.; Simón, M.A. Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) breeding in olive tree plantations. Mammalia 2017, 81, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maass-Lindemann, G. Interrelaciones de la cerámica fenicia en el Occidente mediterráneo. Mainake 2006, 28, 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Fernández, J.J. Identidades, Cultura y Materialidad Cerámica: Las Cogotas y la Edad del Hierro en el Occidente de Iberia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, J.E. (coord.). Saberes, Artes y Costumbres del Olivar Tradicional. SEO/Birdlife. 2018. Available online: https://olivaresvivos.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Anexo-E4-1.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Flores, L. Atenas, ciudad de atenea. In Mito y Política en la Democracia Ateniense Antigua; UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Mateos, D.; Rey Benayas, J.M.; Pérez-Camacho, L.; Montaña, E.D.L.; Rebollo, S.; Cayuela, L. Effects of land use on nocturnal birds in a Mediterranean agricultural landscape. Acta Ornithol. 2011, 46, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, B.B. Rural marginalisation and the role of social innovation; a turn towards nexogenous development and rural reconnection. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 552–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category of Participant | Description/Role | Added Value |

|---|---|---|

| Farmer | Farmers selected for early harvest based on the quality of their fruit. They are responsible for cultivating, tending to and picking the fruit, in other words, up to the point where it is taken to the cooperative. |

|

| Cooperative | Entity that is responsible for processing the fruit and making it into early harvest olive oil. In addition, it is responsible for the management, bottling and sale of the oil. Lastly, the cooperative is responsible for paying the farmer for the processed fruit. |

|

| Customers | Olive oil consumers who are willing to buy this type of product. |

|

| Distributors | Network of distributors and commercial agents who sell the product in different geographical areas. |

|

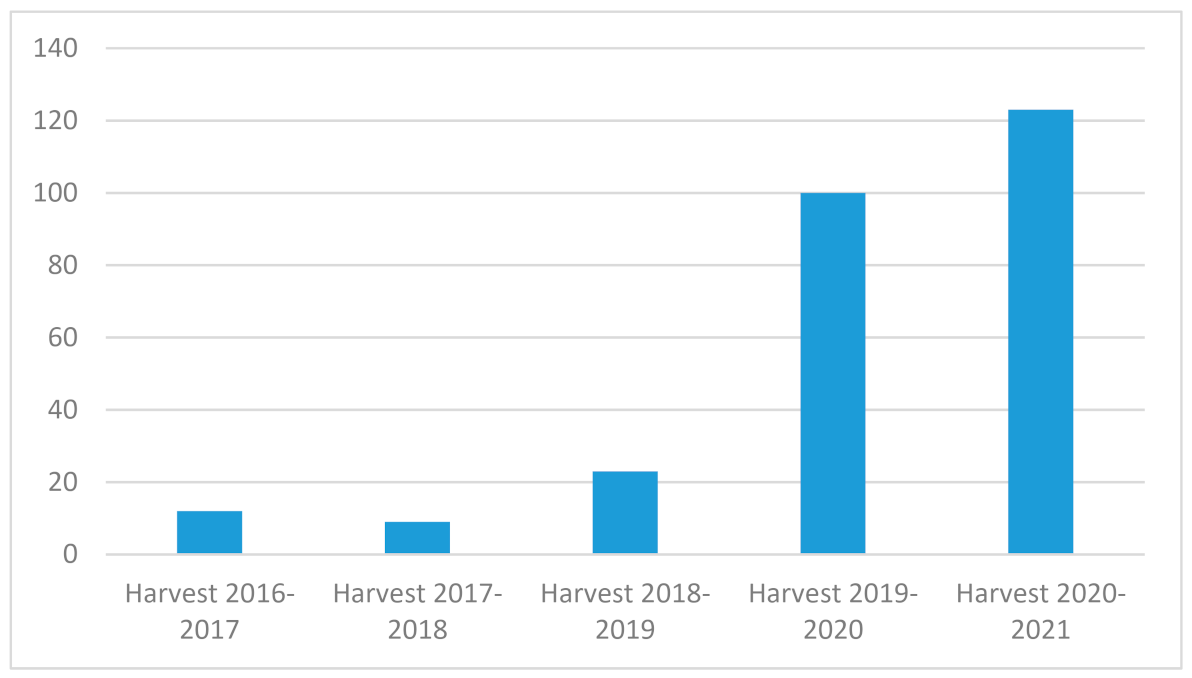

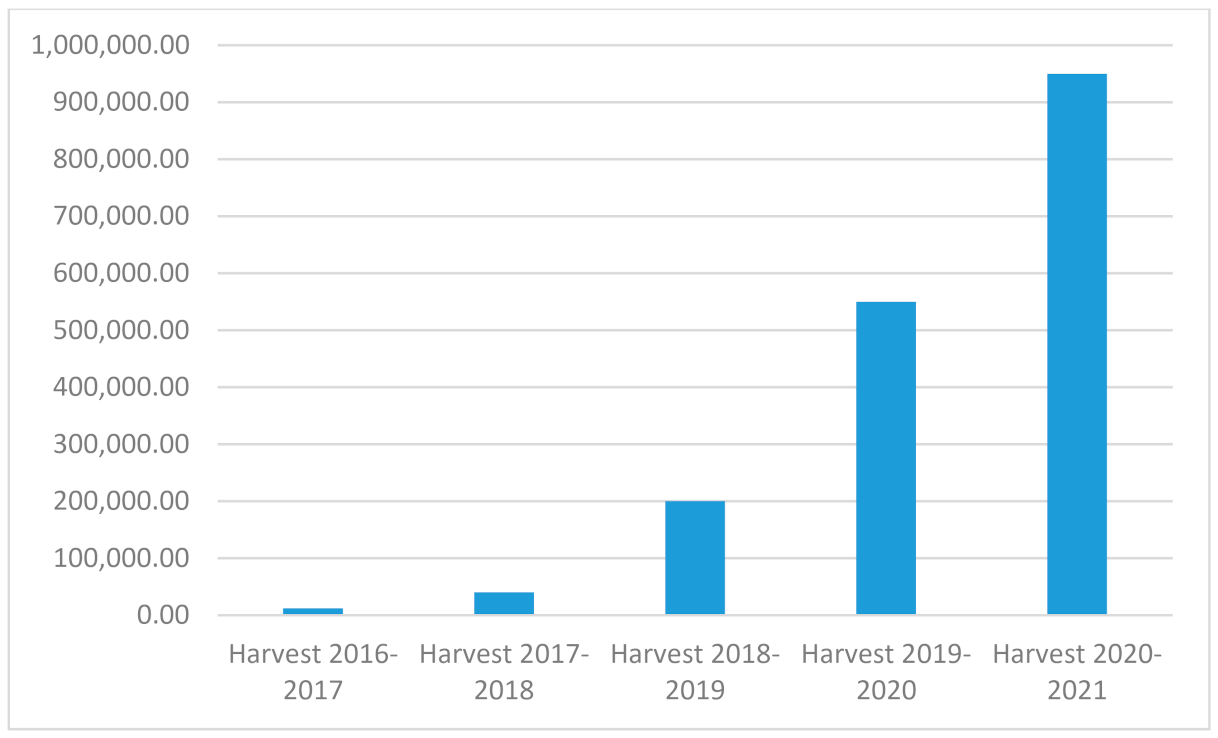

| Harvest Season | Amount Paid per kg of Olives Used to Make First Day of Harvest (€/kg) | Average Amount Paid per kg of Harvested Olives (€/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| 2016–2017 Season | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| 2017–2018 Season | 0.70 | 0.68 |

| 2018–2019 Season | 0.80 | 0.42 |

| 2019–2020 Season | 0.70 | 0.35 |

| 2020–2021 Season | 0.70 | 0.38 |

| No. of bottles of the limited edition: 4000 | Languages: Spanish | Distribution: Spain |

| Printing features: Cotton paper (virgin cotton fibre). Golden stamping. Silver glitter varnish. Four-colour printing. Embossing. Screen-printing varnish. Information card folded in the middle and tied to the bottle with a thread. | |||

| Storytelling: The first edition of Picualia’s First Day of Harvest, produced in 2016, focuses on the figure of the Iberian lynx in the olive groves of Jaén [43]. Specifically, it refers to one particular lynx monitored via a tracking collar by the Lynx Life Project [44]. This lynx lived in the vicinity of Picualia until that year and was the first female of this species to bear a litter in the olive groves. The Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus is the most endangered feline species on the planet and is emblematic of the biodiversity of the Iberian Peninsula. The main motif of the label was designed from notes made in the wild thanks to the collaboration with organizations dedicated to the conservation of this species. | |||

| Added value: 5% of the sales profits go to the Iberian lynx conservation project managed by the Iberian Society for the Study and Conservation of Ecosystems (SIECE). The presentation of this EVOO was accompanied by an exhibition of nature paintings by the designer of the label, which was on display at the premises of the cooperative throughout the 2016/2017 season. | |||

| No. of bottles of the limited edition: 8000 | Languages: Spanish | Distribution: Spain |

| Printing features: Cotton paper (virgin cotton fibre). Golden stamping. Silver glitter varnish. Four-colour printing. Embossing. Screen-printing varnish. Information card folded in the middle and tied to the bottle with a thread. | |||

| Storytelling: This strongly conceptual label pays tribute to the tradition of pottery in the town where the cooperative is located. The use of ceramic vessels to transport goods in the Mediterranean basin is closely linked to the spread of olive groves out of the Fertile Crescent dating back to 3000 BC, when the Phoenicians used their maritime and trade routes to distribute olive plants all along the Mediterranean coast, resulting in the current geographical area dedicated to olive cultivation [45]. The design is also centred around the fingerprints pressed into fired ceramics, representing the historical links between pottery and the bottling and transportation of olive oil. | |||

| Added value: Showcasing of artistic ceramics. A large number of craft potters gathered together to proclaim the history of pottery as a distinctive feature of the local identity. During the presentation of this EVOO, a talk was given by Juan Jesús Padilla Fernández, recipient of the University of Granada’s Award for Excellence for his doctoral thesis on identities, culture and ceramic materiality [46], from whose work this label draws its inspiration. | |||

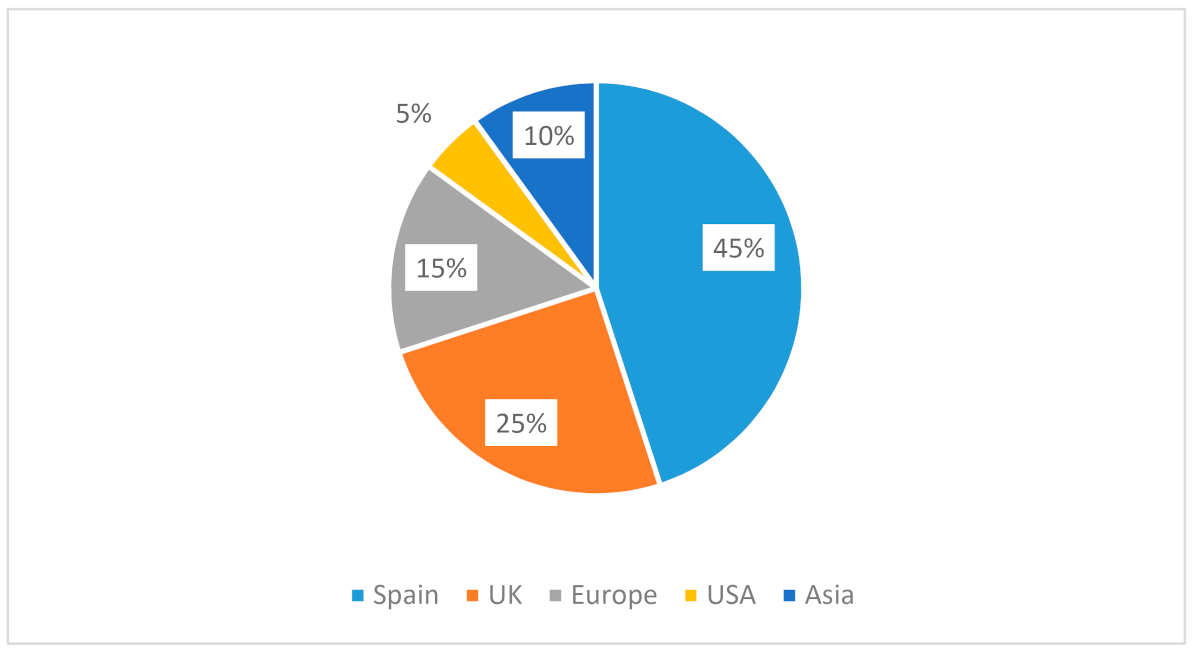

| No. of bottles of the limited edition: 15,000 | Languages: Spanish, English, Arabic. | Distribution: Spain, Europe, USA, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia. |

| Printing features: Tintoretto paper (anti-stain treatment). Golden stamping. Silver glitter varnish. Four-colour printing. Embossing. Screen-printing varnish. Information card folded in the middle and tied to the bottle with a thread. | |||

| Storytelling: Through a colourful illustration of local customs, the daily reality of a couple of Twentieth century labourers is reflected. The image depicts a man and woman, working on equal terms, as well as an imposing centuries-old olive tree and traditional tools used for the ancient work of olive picking. The scene is centred around a tool widely used in pre-industrial harvesting, commonly known in Spanish as a criba (sieve) or limpia. Before the mechanization of olive groves, it was used to separate the olive from the leaves and twigs after harvesting. The picturesque scene is brought to life through the realistic representation of light and shadows, with the light filtering through the branches of the olive tree. The trunk and crown of the tree fill the label, which provides a window on the past and on the wisdom, art and customs linked to traditional olive groves [47]. | |||

| Added value: Showcasing the profession of farmer at a time of falling prices for cultivating olives. Various local cultural associations participated in the presentation of this EVOO, extolling the figure of the farmer through the arts. | |||

| No. of bottles of the limited edition: 20,000 | Languages: Spanish, English, German, French and Arabic. | Distribution: Spain, Europe, USA, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia. |

| Printing features: Tintoretto paper (anti-stain treatment). Golden stamping. Silver glitter varnish. Four-colour printing. Embossing. Screen-printing varnish. Information card folded in the middle and tied to the bottle with a thread. | |||

| Storytelling: The proposal for 2019 represented the figure of an owl emerging from the trunk of an olive tree. A symbolic species linked to olive cultivation and the culture and heritage of the Mediterranean environment, this small nocturnal bird of prey has given rise to sayings passed down from generation to generation, one of the most well known of which is Cada mochuelo a su olivo (literally, “Every owl in its own olive tree”, roughly equivalent to “Every man to his trade”). This label fulfils a dual educational and informational purpose. On the one hand, it recalls the myth of Athena through the symbolic figure of the bird that accompanies the goddess of wisdom, handicraft and warfare [48]. On the other hand, it is aimed at raising awareness of the delicate situation facing the species linked to the olive grove ecosystem; studies investigating their declining populations show how they are threatened with the loss of their habitat due to changes in the management of herbaceous cover crops traditionally used in olive groves [49]. | |||

| Added value: Spreading the message about the delicate situation facing the birdlife and other species associated with the biodiversity of olive grove ecosystems. In addition, a photography exhibition was held in the premises of the cooperative, focused on reflecting the biodiversity of the olive grove ecosystem, with photographs taken by photographers from conservation organizations. | |||

| No. of bottles of the limited edition: 23,000 | Languages: Spanish, English, German, French and Arabic. | Distribution: Spain, Europe, USA, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia. |

| Printing features: Tintoretto paper (anti-stain treatment). Golden stamping. Silver glitter varnish. Four-colour printing. Embossing. Screen-printing varnish. Information card folded in the middle and tied to the bottle with a thread. | |||

| Storytelling: This edition pays tribute to the spirit of sacrifice, professionalism and commitment of healthcare workers during the global COVID-19 pandemic. The image is an illustration of two hands clapping. The outline of the hands encloses a deliberately hazy, somewhat abstract depiction of a group of healthcare professionals. The focus is drawn to the colour palette, dominated by blue, white, grey and turquoise, the standard colours of the protective equipment used by healthcare workers. | |||

| Added value: Picualia decided to donate 5% of the profits of this EVOO to the Branyas Project, the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and Farmacia de Dalt, which is investigating the impact of COVID-19 in care homes for the elderly. | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parrilla-González, J.A.; Ortega-Alonso, D. Social Innovation in Olive Oil Cooperatives: A Case Study in Southern Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3934. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073934

Parrilla-González JA, Ortega-Alonso D. Social Innovation in Olive Oil Cooperatives: A Case Study in Southern Spain. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3934. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073934

Chicago/Turabian StyleParrilla-González, Juan Antonio, and Diego Ortega-Alonso. 2021. "Social Innovation in Olive Oil Cooperatives: A Case Study in Southern Spain" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3934. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073934

APA StyleParrilla-González, J. A., & Ortega-Alonso, D. (2021). Social Innovation in Olive Oil Cooperatives: A Case Study in Southern Spain. Sustainability, 13(7), 3934. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073934