1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and the containment measures necessary to stop its expansion have had significant externalities for individuals, society, organisations and markets. For all these actors, the epidemic is an unpredictable exogenous event whose specific characteristics are unique and lead to a rethinking of new forms of life. In the business field, COVID-19 is more important than any other global crisis that we have known and requires new strategies in which the fundamentals of corporate social responsibility (CSR) must be rethought and strengthened as patterns of long-term business success and social welfare [

1,

2,

3].

In the current economic scenario, in favour of the development of a responsible business model, beyond the instrumental and institutional or relational reasons that can lead companies to get involved in CSR [

4,

5,

6] are the ethical and moral motives of the company directors. In this sense, CEOs are the agents who have the authority and power to determine policies and frame them within corporate strategy, as they are able to create the context (structure and necessary incentives) within which they are executed [

7,

8]. An inspiring, transformative leader, who is concerned about stakeholders, fosters this spirit within companies, leading to a reinforcement of transformational leadership with respect to the effects of transactional leadership [

9].

Thus, various studies indicate that the CEO’s moral values and beliefs explain the formulation, adoption and implementation of responsible policies (i.e., [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]). However, the pandemic has meant that all companies are affected by an event that threatens their stability and that of the business sector in which it operates, both nationally and globally. This means that business leaders have had to implement modifications to their corporate strategies and new organisational management models to face a new reality.

At the same time, they have had to establish a communication model that ensures a dialogue with their stakeholders, aimed at transmitting confidence and control over the current situation. Tensions due to COVID-19 create anxiety and test the emotions of company investors and other stakeholders; therefore, external communication from senior management is essential as it provides information on the interpretation of the current situation and planned actions [

15]. This decision is especially relevant for large companies, which are more visible and monitored by pressure groups, financial agents and the media.

Framed in the intersection of academic interests, the present work aimed to analyse the communication strategies of CEOs with their stakeholders in the context of an unprecedented crisis due to COVID-19, determining whether this discourse is aligned with the investment and/or divestment decisions that have been made from an economic, social and environmental point of view and whether there were selfish attributions on the part of the manager. To do this, a sentiment analysis was carried out both of the discourse used and of the nature of the operational and strategic decisions that have been made.

In this regard, we know that the decisions made by each company differed in the approach adopted, leading to divestments versus other initiatives aimed at acting as a driving force of the economy. There are numerous examples of solidarity companies in unfavourable economic times [

1,

3]. In this sense, according to Heider’s [

16] attribution theory, managers may have used a selfish news attribution strategy. Thus, one might think that companies that have reported bad news regarding the implementation of cost and investment containment plans, restrictions on the distribution of dividends, etc., may have adopted a rhetoric aimed at outsourcing the responsibilities of these decisions to maintain legitimacy and their business reputation, as other authors have shown in disaster situations (i.e., [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]). Additionally, solidarity companies may have adopted a strategy of self-exaltation, using a greater number of internal attributions to explain the actions taken in a period of crisis, with a focus aimed at increasing, in general, the importance of the business fabric for society in unknown adverse moments and, in particular, the image and reputation of the company and its managers.

The results obtained for listed Spanish companies showed that the CEOs of the companies who made decisions focused on safeguarding the interests of shareholders and investors, guaranteeing the survival of the company by containing investments and expenses, based their communication strategy on an informative letter aimed mainly at this interest group with selfish attributions that justified their decisions due to the adverse situation that COVID-19 has caused. This informative strategy can be an important sign of an organisation’s sincere commitment to avoid greater evils and transmit a correct message in that the effect of communicating unfavourable news is corrected through a speech of self-protection.

Regarding the companies that chose to modify their policies, actions and strategy with economic and solidarity criteria, we have shown that they opted for a dynamic and constant communication strategy, using a self-enhancement discourse in which their commitment to society is highlighted despite the existence of negative external circumstances for the company.

For those companies whose decisions were aimed at increasing investment, guaranteeing employment and being responsible agents with society, although they also opted for a dynamic and constant communication strategy, the adopted discourse is one of self-verification, focused on making known to stakeholders their business commitments, avoiding references to the efforts involved in implementing these decisions in the current crisis context. Additionally, the CEOs of these companies chose to complement the informative channels based on letters and web content with the recording of videos in which the CEO addresses the different interest groups to inform them about the company’s commitment to helping society.

The results obtained contribute to the previous literature in a very valuable way. First, business communication strategies are analysed in an environment characterised by an unprecedented health, economic and social crisis that affects the entire world population, an environment whose characteristics had not been previously analysed. Additionally, communication and operational strategies are considered together, which allows taking into consideration the response that companies have had to the consequences of this new scenario and their way of communicating it, as well as the link with the manager’s sentiment. Given the diversity of the decisions that have been made, both self-protection and self-enhancement strategies can be observed. In this sense, the existence of selfish attributions in the discourse with stakeholders has been evidenced, thereby identifying the existence of a self-verification communication strategy aimed at faithfully informing stakeholders of corporate action that is typical of more pessimistic CEOs. Finally, it has been identified that the communication channels used with stakeholders and their degree of innovation are strongly linked to economic commitments vs. solidarity that could be closely related to the values and optimism of the CEO.

2. CSR as a Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has refocused governments as key actors in addressing the great challenges of this global crisis. On the other hand, it is clear that the social responsibility of companies in the pandemic has been to act together with governments and other actors to address the containment of the epidemic and its consequences, guaranteeing employment, investing in procedures and equipment that guarantee the safety of workers and clients, producing socially useful products and collaborating with charities to help vulnerable groups [

3].

As such, the COVID-19 pandemic calls into question the core purpose of what a business is and what role it should play in society [

22]. In this context of global crisis, companies must focus on how they can do good—a notion more critical than ever—and it is the duty of researchers to deepen their understanding of this action [

2]. It is essential that the CSR strategy is integrated, forms part of the routines and operations of the company and involves the participation of human resources so that the economic growth of all agents, including companies, is possible [

1].

In this sense, CSR is conceived as a business strategy that groups together different actions aimed at promoting some aspect of the social good beyond the interests of the company and what is stipulated in the law [

23]. Business initiatives in this regard have shown a growing trajectory in recent decades, although their impact has been marginal [

24], and they have even been accompanied by inappropriate behaviour and corporate scandals [

25].

For this reason, companies are frequently criticised for not leading by example (i.e., [

26,

27]), with reference being made to greenwashing as a practice in which the commitment to CSR is easy and inexpensive since it is symbolic in fact and sophisticated in word [

28,

29]. Reference is also made to silent companies that do not report all their actions to avoid potential risks derived from stakeholders creating additional expectations that the company cannot satisfy, although the customary state is that an “uncoupling” [

30,

31] indicative of an incongruity between doing and saying, and, in addition, impression management practices based on different visual and narrative techniques are observed (i.e., [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]).

Due to the relevance that environmental, social and ethical aspects have in today’s society, CSR has become a key element in the business environment [

37,

38], which entails companies deciding to invest in CSR when the benefits exceed the costs [

39,

40]. Thus, many companies invest in communicating their CSR activities to create a positive image, mainly assuming the costs associated with advertising, marketing, communication, reports and dissemination of CSR activities [

28] and being able to totally or partially avoid the costs of implementing CSR strategies [

41] concerning the adaptation of organisational processes affecting the entire value chain, sustainable investments in process and product, etc., as well as more philanthropic actions oriented to a common good, such as resources allocated to public policy issues like health, education and public infrastructure.

However, the literature concurs in stating that companies engage in CSR basically for three non-exclusive reasons [

42]: (i) instrumental reasons that defend that CSR allows obtaining economic and reputational benefits that translate into increases in business competitiveness [

43]; (ii) institutional or relational reasons derived from external pressures that force companies to adapt to the expectations of stakeholders and institutions [

44,

45,

46]; and (iii) ethical and moral reasons, mainly associated with the directors and/or owners of the company [

10].

In the unprecedented crisis situation that the pandemic has entailed, the total or partial stoppage of economic activity and the consequent drop in turnover are indicative that the intrinsic characteristics of managers are the main determinants of business decisions taken in 2020. In this sense, the upper echelons theory argues that the particularities of each manager mean that the strategic decisions made within companies are heterogeneous among themselves, leading to different performances [

47]. The foundation of this theory implies that executives have limited rationality and are susceptible to cognitive biases [

48]; consequently, their strategic choices reflect their values and perceptions.

3. The Discourse, Values and Perceptions of CEOs and CSR in the Age of COVID-19

Although there is an interest in analysing the characteristics of the executive team as a whole, researchers recognise that CEOs have a separate and significant influence on decision-making processes [

49]. The approach that has been undertaken for the particular case of sustainability has shown the variability in commitment to CSR according to political ideology, narcissism, leadership, gender, hubris, personal values and the ability of the CEO, among other aspects [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59].

In line with previous empirical evidence, the authority, power, and leadership of CEOs have determined the decisions that have been made with respect to corporate strategy [

7,

8]. Since these individual characteristics are no longer present evenly across the entire management team, they tend to belong mainly to the CEO [

60,

61], thereby eventually limiting the influence of the rest of the executives [

62,

63]. CEOs possess the charisma, network of contacts, functional expertise and experience necessary to drive change [

64,

65,

66,

67].

However, Carpenter et al. [

68] and Arena et al. [

58] have argued that the use of these characteristics supposes a “black box” approach that establishes a link between the characteristics of the CEO and CSR without unravelling the specific mechanisms that lead the CEO to commit to certain strategies that would be related to psychological and cognitive attributes. Thus, Graham et al. [

69], Gerstner et al. [

70] and Kraiczy et al. [

71], among others, have shown that the optimism of the CEO and their preference for risk is one of the most important drivers of innovation and business transformation. Although given the difficulty of measuring these values and cognitions, as they are not directly observable and are difficult to measure, academics use proxies of observable characteristics, one of these options being the analysis of their letter to shareholders along with the existence of selfish attributions and their relation to performance.

In general, the results reported that there are patterns in the discourses of the managers in their annual reports according to whether their result was good or bad, in which are identified the differences in degrees of legality [

72,

73] in the emphasised themes [

74] and in the narrative strategies [

75]. Although the evidence from Lasking [

75] indicated that it cannot be concluded that there are different patterns, it is necessary to consider different contexts and include an analysis of sentiments in management communications (i.e., [

76,

77,

78]), bearing in mind the stress and discretion that may exist in times of business crisis [

15].

In this study, in line with the latter author, we argue that during a period of epidemic, managerial sentiment, which is a belief that has arisen from emotions, determines how they perceive external situations, which influences their expectations concerning the evolution of the company [

15], thereby determining the decisions made. Thus, the cognitive traits and optimism of the CEO can be specified through sentiment analysis of their speech in the toughest moments of the pandemic, through which the CEO communicates the decisions they have made in relation to corporate strategy and the future of the company.

In this sense, research on the human brain has revealed that the human amygdala plays a crucial role in the acquisition of responses conditioned by adverse situations that are critical for our survival because synaptic plasticity establishes the links between neutral signals and aversive events. This means that some executives, when faced with the effects that COVID-19 supposes on the normal conduct of the company’s activity, acted with a view to satisfying immediate needs focused on measures that would guarantee survival. The most optimistic CEOs focused on actions and strategies with long-term objectives, considering the performance of responsible actions. Additionally, these managers may have designed different communication strategies with their stakeholders, depending on whether their moral decisions were more or less egocentric and their need to emphasise prosocial and trusting behaviours was part of a protection mechanism, which is usually coupled with less generosity.

Thus, our research on the egoistic attributions of the management is oriented towards determining the degree of influence that the COVID-19 environment might have exerted on the attributions since, for the explanations to be plausible, in a negative context the bad news associated with divestment decisions, lay-offs, etc., should be attributed more to external factors [

79,

80,

81,

82]. Additionally, news of a positive responsible decision linked to the external negative aspects of the situation caused by the pandemic can be justified for internal reasons as a strategy to self-praise the manager (enhancement).

This selfish behaviour that less optimistic or egocentric CEOs could have adopted can be explained in psychology from three points of view: informational, cognitive and motivational or opportunistic. In this sense, through selfish attributions, management sends signals to the market about its ability to control the company’s operations and future prospects, which makes them a key element in the company’s communication strategy [

83,

84], influencing with their discourse the perceptions of the user of the information, using reasons abroad to justify unwanted decisions or give them greater value [

81]. Explanations that researchers have confirmed are very useful for investors, analysts and other financial agents when correcting asymmetric information problems [

83,

84,

85,

86,

87].

4. Research Design

4.1. Population and Sample

The main purpose of this work was to find emotional patterns in the discourses of CEOs when facing the problems related to COVID-19 and its relationship with the operational and strategic decisions they made. For this, the 159 Spanish companies whose securities are listed on the Madrid Stock Exchange were selected as the target population.

The selection of the Spanish companies was due to their significant involvement and collaboration with the public sector and different NGOs to face the profound health, economic and social crisis that the COVID-19 pandemic caused in Spain [

3]. The decision to focus mainly on large listed companies was a consequence of the fact that they were the companies with the greatest resources and capacities to promote actions aimed at the well-being of the entire Spanish society [

36].

Although information was obtained for 100 companies, the final sample corresponded to 87 companies that reported in detail about their CSR actions on their website, generally in the News section. The brief content of the informative notes of the 13 companies not considered made it difficult to determine the textual analysis, which is why they were not considered in the study.

4.2. Methodology

The analysis technique used corresponds to a content analysis of the information available on the website of the selected companies. This technique allows the interpretation of written and recorded texts with the capacity to contain content that, read, observed and interpreted properly, opens the doors to knowledge concerning business decisions. The content analysis was based on reading as an instrument for collecting systematic, objective, replicable and valid information, carried out according to the scientific method.

Once the operational and strategic decisions made by the companies were identified, the coding and subsequent treatment was based on the two types of categorisation of the actions proposed by García-Sánchez and García-Sánchez [

3]. The first of them involved categorising the actions according to the interest group to which they were directed and that these authors have classified as investors, employees, clients, suppliers and collaborators, and society. The second involved a classification taking into consideration the manager’s values, intrinsically related to the objectives pursued with the decision taken: economic and legal responsibilities, ethical CSR, commercial CSR and altruistic or philanthropic CSR. Additionally, these categories were grouped according to negative nature (adjustments, expenses cuts, etc.) vs. positive nature (donations, volunteering, etc.) that the CEO communicates to their stakeholders. This manual classification was contrasted with that from the use of a sentiment analysis programme.

In relation to communication strategies, a textual data analysis programme was used. This analysis consisted of separating the words contained in each of the reports and knowing the number of times they were used, which resulted in a matrix of lexical data, each of the different words used in rows and the different companies in columns [

88]. The row column confluence corresponds to the absolute frequency. These initial data were subjected to a preprocessing that consisted of eliminating the empty words of the language such as prepositions, conjunctions, pronouns, etc., with only the semantically loaded textual elements remaining. A lemmatisation was applied to this group of elements so that several words with a common origin can be reduced to a single term, based on the fact that they all have a semantic relationship (e.g., good-great: good).

The results obtained with the text software, once the text cleaning and debugging process had been carried out, allowed for observing that companies used a total of 2830 words to describe how their resources dealt with COVID-19. Once grouped, the parsed text consisted of 350 different words.

To study the existence of selfish attributions in the communications of these companies, their reports were evaluated with a sentiment analysis, determining the existence of a negative connotation in the language used when presenting a specific business decision, indicative of self-protection or self-exaltation practices, depending on the nature of the decision made. Additionally, the AFINN dictionary was used in order to determine different degrees of negativity/positivity in the information communicated relative to a specific action [

89]. To do this, a numerical value between −5 and 5 was assigned to each of the words obtained, with −5 being extremely negative and 5 extremely positive.

5. Results

5.1. Analysis of the Existence of External Communication Policies and Communication Channels

The analysis of the public information available in relation to COVID-19 showed that only 100 of the 160 companies listed on the Madrid Stock Exchange had designed an external communication strategy. In the case of 13 companies, the note or informative comment was so brief and general that it did not allow an exact determination of the corporate decisions taken. In general, the absence of external communication and the presence of brief information notes were characteristic of non-Spanish listed companies.

The analysis of the content of the information available on the websites for the rest of the Spanish corporations allowed us to identify the existence of different procedures to communicate the decisions of the management team to its stakeholders. First, we identified the existence of crisis declaration letters that could or could not be complemented with an updated section of news on the corporate website and in which a video of the CEOs (or similar format) could occasionally be included to communicate with the groups of interest.

The crisis declaration letters in some cases exclusively focused on exposing the actions and measures that were going to be implemented from an economic point of view, being the only communication action carried out by these companies. In other cases, these letters, in addition to the necessary economic measures, included specific action commitments related to socially responsible actions. These companies used the corporate website to constantly keep their stakeholders informed by incorporating podcasts, webinars, etc.

5.2. Selfish Attributions in the CEO’s Speech According to the Nature of Operational and Strategic Decisions

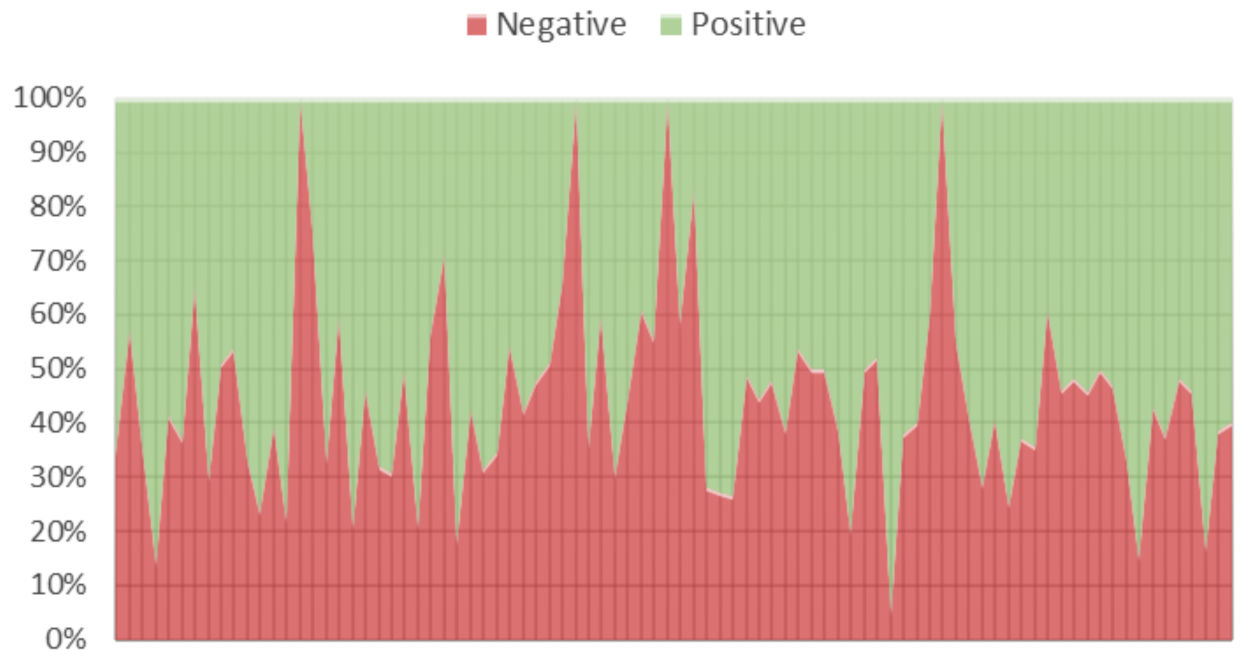

In relation to the discourses used by each of the companies, we carried out an exploratory analysis, differentiating by the high presence or absence of terms with negative connotations related to the pandemic, such as confinement, etc. Unlike the CSR reportings, where positive discourse was prioritised, we found in this case that communications with stakeholders by more than 50% of companies were carried out with a discourse focused on the adversities of the pandemic. Additionally, taking into account the degree of negative/positive sentiment of the terms used in business communications, in

Figure 1 it can be seen that the use of positive terms coexists with negative terms in the speeches.

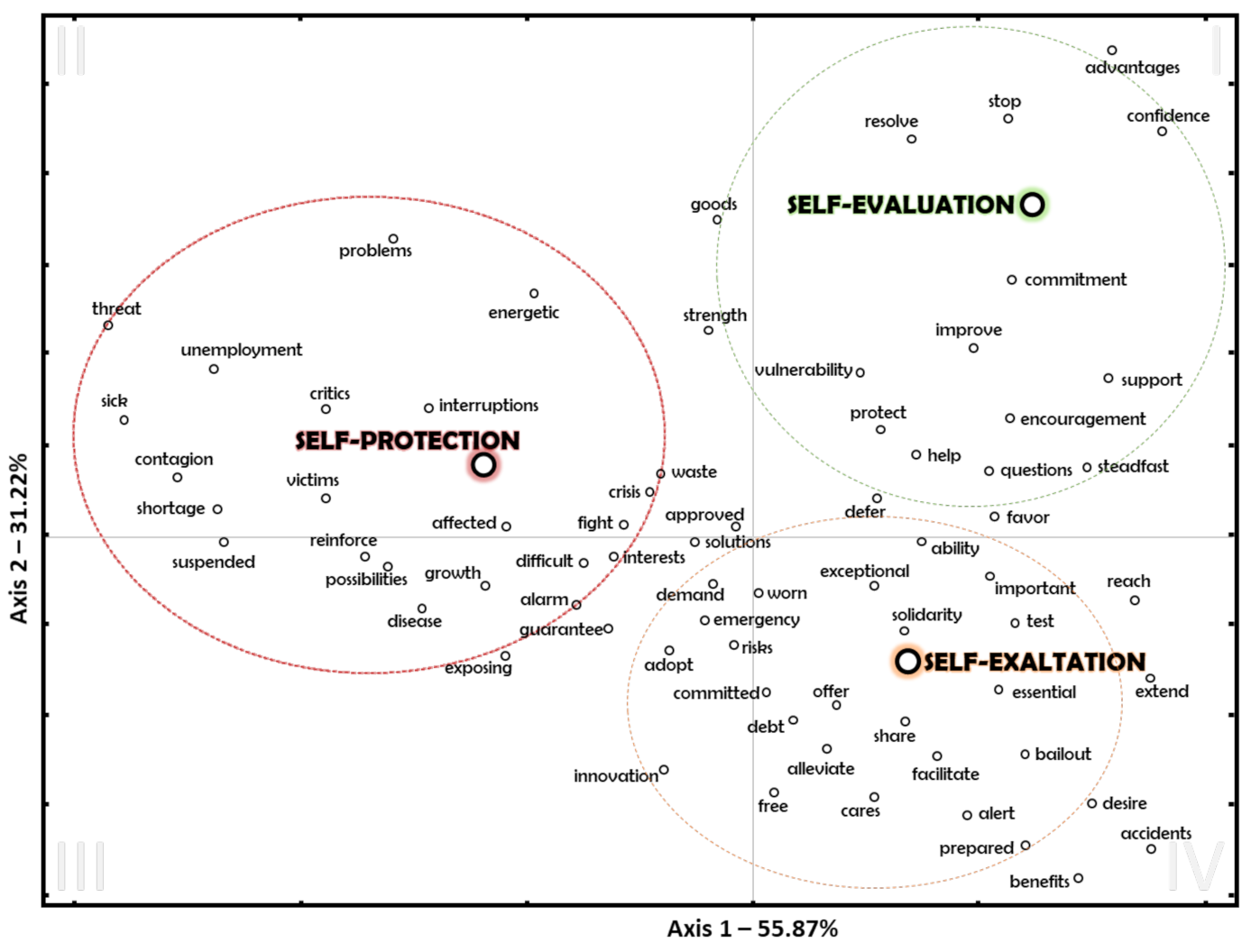

On the other hand, the terms and expressions that companies used in their external communications to inform about their corporate decisions were analysed. The results obtained from the manual analysis showed important differences in the speeches of the CEOs in their attempt to face the consequences of COVID-19, identifying self-serving attributions focused on both self-protection and self-enhancement. Additionally, it was observed that a smaller number of companies did not opt for this discourse, but instead self-verification practices were identified that would imply that the CEO wanted to be known and understood by others according to their firm beliefs and feelings about the decisions made and avoiding the use of selfish attributions.

In order to contrast the robustness of the analysis and to understand the observed differences, we carried out a statistical analysis of textual data from a factorial correspondence analysis (FCA). The purpose of this technique is a two-dimensional representation of the lexical matrix and identification of the most relevant terms in business discourse. For this, the FCA works with profiles—the distribution of relative frequencies of a line in a table (row or column) in relation to its marginal total—and the objective is to obtain a geometric representation that facilitates the interpretation of the numerical information of a lexical table, looking for axes with which the maximum dispersion of point profiles around the centroid is achieved, with the least loss of information. The metric used is the chi-square distance, a weighted Euclidean distance, which allows infrequent words to be weighted more and more frequent words less. The chi-square distance neutralises all distortions in the graphical representation. This led us to the following representation, which absorbs 87% inertia (see

Table 1).

Complementarily, this technique allows a visual representation of the identified terms, as can be seen in

Figure 2. From this representation, taking into account the positive and negative nature of the operational strategies, the type of discourse for which it is used is identified by the proximity of the words to these points, indicative of more frequent use. Thus, based on the terms and expressions that CEOs used and the nature of the decisions they made, we categorised companies according to the three types of discourse identified: (i) “self-protection”: companies whose operational decisions were focused on lay-offs, divestments, restrictions on dividend policy, etc., combining them with negative terms related to the pandemic and its consequences; (ii) “self-exaltation”: companies whose operational decisions combined economic measures similar to those of the previous group and responsible actions with society, incorporating terms associated with the negative aspects of the pandemic to highlight their responsible commitments; and (iii) “self-evaluation”: companies whose economic measures were expansive and accompanied by solidarity actions, avoiding references to the negative externalities of COVID-19.

The CEOs of the self-evaluation cluster of companies were the ones with the least use of terms with negative sentiment, limited to a percentage equal to or less than 25% of the total words used. In addition, it can be observed that the terms used to inform their decisions corresponded to descriptions of actions, such as offering “help” to those most vulnerable people, strong “commitment” in the present and great “confidence” in the future, showing greater safety in working conditions, greater concern in guaranteeing their services, “support” in foundations, etc., all in the search for solutions to “improve” the current situation, providing all the possible “advantages” within their services. In reference to their negative discourse, they used softer negative words than the rest of the companies, such as “stop” the spread or temporarily stop production. They mentioned that we are in a situation of “vulnerability”, and we must “protect” and promote a safe and healthy workplace—comments that in context are related to an individual’s actions and are not used as an exaltation strategy.

The companies grouped in the “self-exaltation” cluster had a less optimistic and innovative discourse. They spoke of “sharing” actions, reflections, “solutions” coming from agreements, of carrying out “tests” to protect the health of all employees, especially health workers, and the creation of value for a society with corporate “solidarity” and power, to “facilitate” the day-to-day life of both employees (such as teleworking or preventing health workers from having to buy food or cook and thus have more time off so that they can continue serving with all their dedication) and customers (postpone the payment of bills, the possibility of returning to regular payments after the situation has returned to normal, etc.), working on the production of new “offers”, such as withdrawing money “free” from any ATM in the country during the state of alarm or electrical and gas repairs for a year, among many others. The discourse of these companies referred to the crisis, given the presence of negative terms, such as avoiding “alert” situations, preventing occupational “risks”, minimising “emergency” situations in the event of “exceptional” situations arising from the pandemic and working on “essential” services. Further, part of the report highlights the “debt” and the possible “bailouts” to it or aid to other companies.

Finally, the companies in the cluster identified as “self-protection”, which accounted for 40% of the sample, presented a report in which negative sentiment exceeded 50% of the content of their speech. One of the main concerns was to “reinforce” the service, production and maintenance of economic activity, always considering the “interests” of its stakeholders, finding “solutions” and minimizing “interruptions” in its daily work. In addition, these companies used their communications to emphasize their decisive role in the “fight” against the coronavirus and that they maintained their commitment to “growth” and shareholder-oriented value creation. If those terms are the ones that can be considered more positive, the negative sentiment had a greater presence in their reports, where alarming words stand out, such as the risk of possible “contagions” or the “threat” or “problems” that the virus triggers. They spoke of “unemployment”, of the destruction of jobs due to the health emergency with the spread of the “disease”, or that certain conditions that have been imposed on us in the time of “crisis” may persist over time. They touched on topics such as the “shortage” of medical supplies, supplies, working capital, and offer professional help; they talked about the importance of the removal and elimination of “waste”, especially from hospital centres since companies have “suspended” some of their services.

5.3. Analysis of the Self-Attributions of the CEO in Their Discourse with the Different Stakeholders

The feeling when using either term is really interesting in order to know the forecasts and actions of organisations in their efforts to help overcome the situation stemming from COVID-19 and the selfish or unselfish attributions that CEOs can make in their discourse. Along these lines, this analysis aimed at identifying business decisions by focusing on their commitment to the different interest groups, evaluating the measures they adopted and the discourse they used in each one of them in order to determine whether selfish attributions were associated with certain stakeholders.

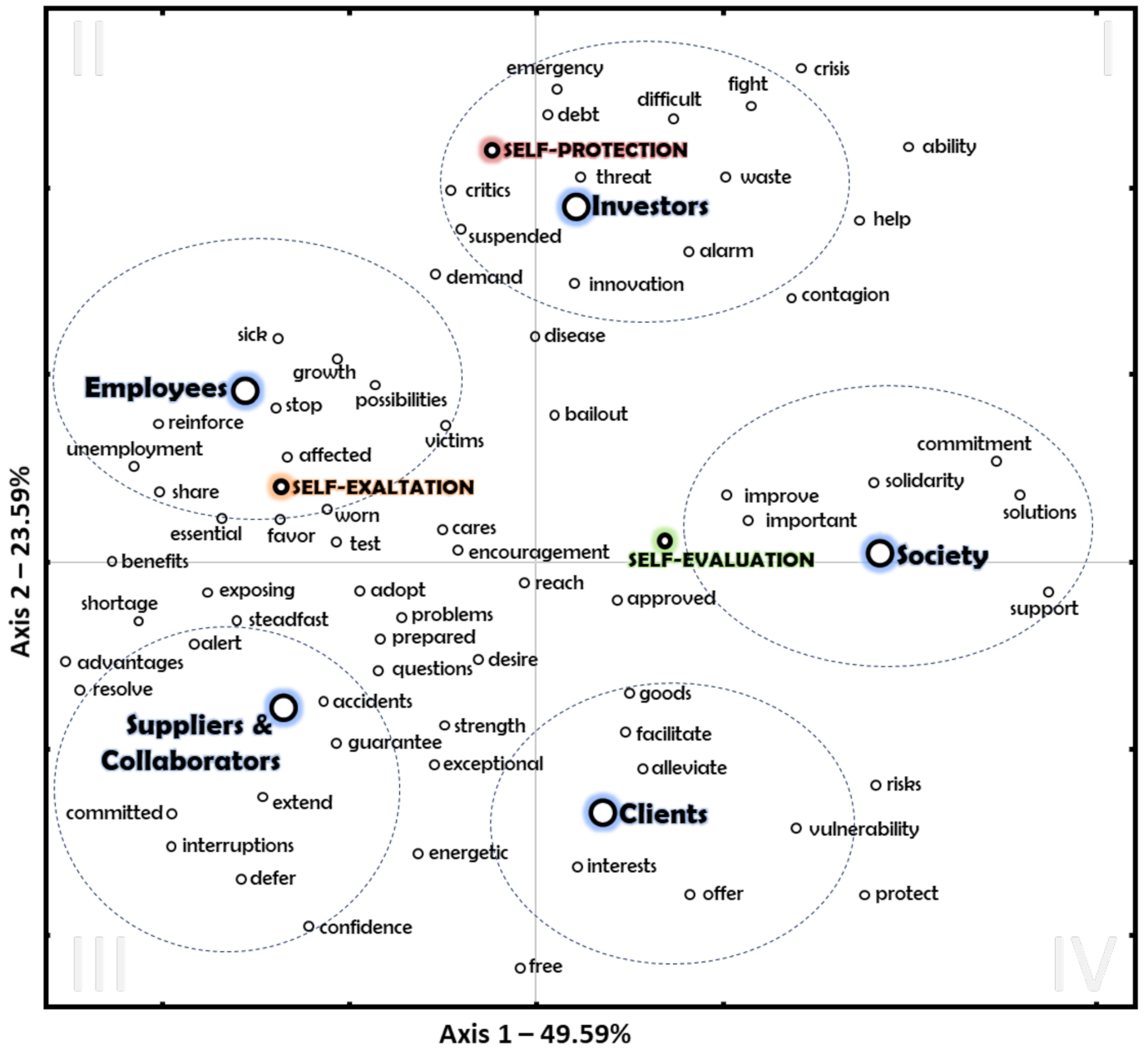

For this, the operational decisions were classified according to the impact they had on stakeholders: investors, employees, clients, suppliers and collaborators, and society. For this study, following the information in the article by García-Sánchez and García- Sánchez [

3], the commitments to each stakeholder were identified as follows: (i) economic measures related to investors; (ii) measures related to the occupational safety of employees; (iii) commercial measures in order to facilitate customer service and security; (iv) guarantees of continuity with suppliers; and, finally, (v) social initiatives, such as collaboration with the public sector, foundations and aid in the fight against the pandemic. For each of these groups, the textual analysis as detailed in the previous section was carried out, through which different patterns were found in the connotation of the speeches used. Statistically, the factorial analysis of correspondences with the objective of delving into the discourses used by companies in relation to their stakeholders has an optimal quality of representation and collects 73% of the total inertia with the first two axes (see

Table 2).

The visual representation of this analysis in

Figure 3 allows us to observe important differences in the connotation of the discourse used, with the use of a self-protection approach being common in companies that sought to guarantee only the interests of shareholders and investors; a speech of self-exaltation in those companies with greater concern for their employees, suppliers and, to a lesser extent, customers; and reports where the self-evaluation discourse predominates for companies whose initiatives were mainly related to society.

In the upper half of the figure, there is a point that refers to all the companies whose main concern was centred on economic measures to guarantee survival and reassure their investors. These companies used a discourse based on the use of excuses focused on the negative situations caused by COVID-19 and mentioning the possible impacts of the health “crisis” on the company’s activities and how they may be affected by the public health “emergency” situation. In the CEO’s speech, resignation and justifications were noted, saying that given the current situation they must react to this “threat” and face costs, finding themselves immersed in “debt”. These reports show apologies and indirect tactics alluding to the “difficult” situation, with prosocial behaviours promoting “help” programmes to cover the highest priority health needs to combat the disease by purchasing critical medical equipment for different hospitals in their “fight” against the pandemic, thereby showing the use of a self-protection strategy aimed at convincing stakeholders that their decisions were due to external forces.

In the left half of the figure, we find the companies that focused their efforts on their employees, suppliers and partners. The discourse distanced itself from the previous one by informing its employees of the labour measures used to guarantee job security. They also focused their discourse on covering people’s basic needs in these difficult days, especially the “sick” and the groups most “affected” by the coronavirus, helping to “stop” the spread of the disease by complying at all times with the recommendations of governments and health authorities, facilitating tests and all “essential” services. These companies offered the “possibility” of working from home whenever technology allowed. In the same way, they recognised the commitment and responsibility of their employees who physically went to their workplace every day and tried to “reinforce” their situation with bonuses in the salary corresponding to the period of the state of alarm. Others assumed the cost of private transport or parking spaces for employees who needed it and thus avoided the use of public transport, or advance payments for unemployment or pension payments.

In the third quadrant, where the suppliers and collaborators are positioned, are the companies that ensured that they had contingency plans to “guarantee” the continuity of their activity, with measures to minimise risk and new organisational procedures, as well as communication protocols related to incidents. Many of these companies played an important role as essential services and showed their commitment to continue guaranteeing production with minimal delays or “interruptions” in supply and, with this, the correct functioning of their services. They undertook to “resolve” any “questions” about their action protocols and offered all the security guarantees to access their products and services.

The companies most committed to their customers are located in the fourth quadrant. In their speech, they prioritised that this crisis would be impossible to overcome if the production of the “goods” and services that citizens need were to be paralysed. They especially focused on “protecting” the elderly, children, youth and families with greater levels of “vulnerability” or those at “risk” of exclusion, “free” electricity and gas supplies, withdrawing money for free at any ATM, “offers” of beds available in hotels for use as hospitals, offers on telephone services, other measures aimed at “alleviating” the financial situation of clients through the extension of payment due dates, automatic deferrals and the elimination of interest of installments for loans and card payments, etc.

Finally, located in the right half of the figure, we find the companies with the greatest involvement in social actions, which showed the most positive discourse in the study. They reported on their “solidarity” campaigns in contributing to the fight against the pandemic in order to “improve” the quality of life for citizens via numerous “support” programmes, donations to equipment and research projects for the development of a vaccine, logistical support for the transport of materials from other countries, foundations involved in the donation of material for the manufacture of sanitary masks, food donations, help for the homeless, etc. They presented a joint “commitment” to promote ecological and sustainable solutions in the European Union’s strategy for recovery after the health crisis caused by the coronavirus; climate change and the defence of biodiversity were the pillars of the policies that they intend to promote and implement. They showed in their reports that what was really “important” was putting all these initiatives in motion to help society in all possible ways and their passion. These companies reported that they were committed to generating responsible and solid economic activity, with a firm commitment to quality work for their employees, as well as the support and promotion of various foundations.

5.4. Analysis of the Self-Attributions of the CEO and the Objectives of Their Decisions

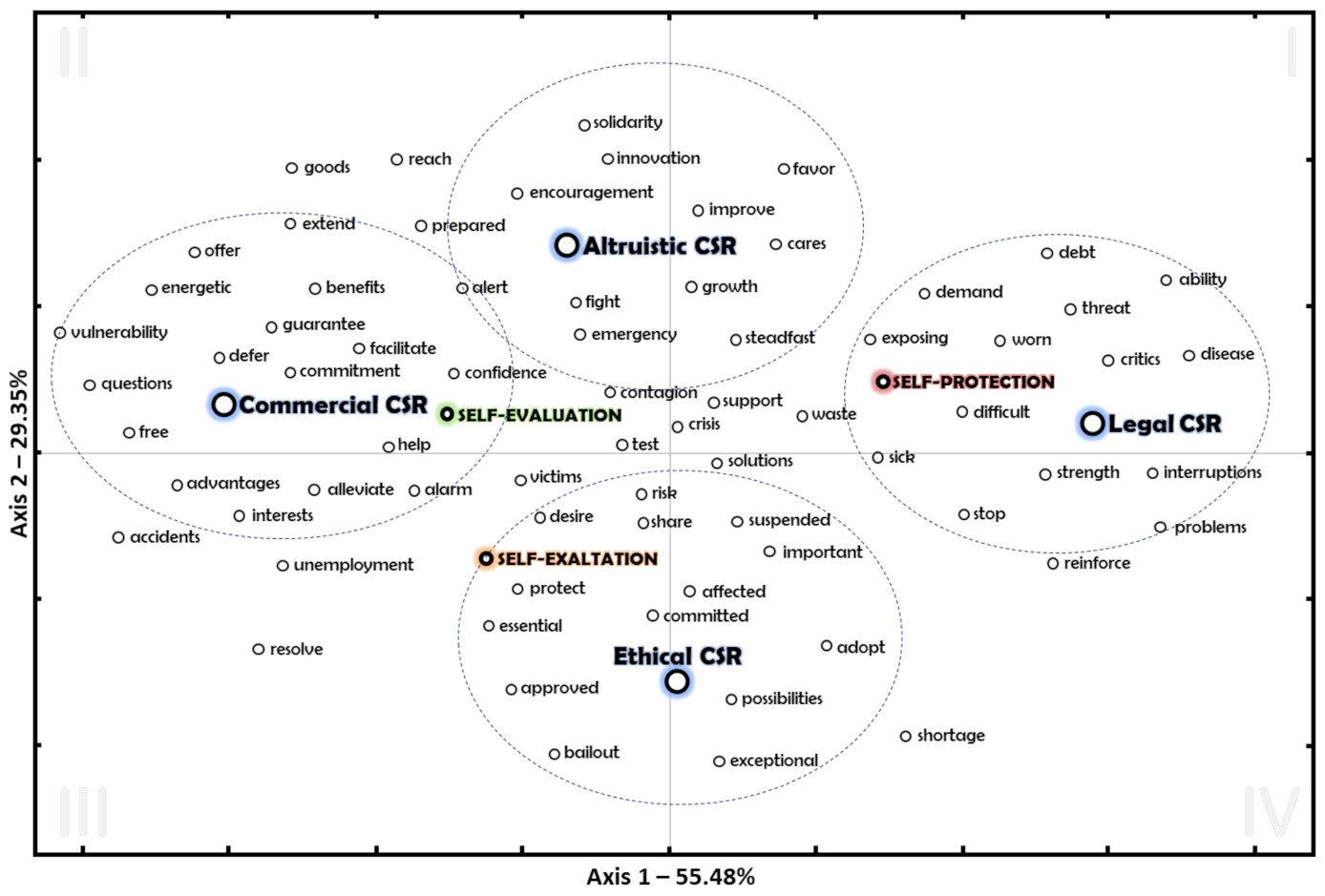

Once the responsible commitment of companies to their stakeholders has been analysed and the connotation and strategies they use are known, we change our focus to the different practices that these companies carry out and whose effects may differ according to the interests of the CEOs. Thus, CSR practices have been grouped into four types [

3]: (i) economic and legal responsibilities or “legal CSR” that identifies those decisions aimed at guaranteeing the interests of shareholders, employees and clients in accordance with current regulations; (ii) commercial CSR for actions closely related to products and services; (iii) the ethical practices of CSR for fair and equitable actions in order to avoid damages; and (iv) altruistic CSR for philanthropic actions aimed at preventing potential harm and alleviating negative externalities that affect the welfare state.

In continuing with the analyses of this research and focusing on knowing what type of discourse companies used based on the ultimate objectives of their practices, we repeated the previous analyses and considered whether business decisions were more commercial, prioritised ethics, had an altruistic approach or focused on legal aspect. In addition, the variables that quantified the connotation of the study were added in an illustrative way (see

Figure 4). This figure shows an optimal quality of representation and collects 85% of the total inertia with the first two axes (see

Table 3).

In this regard, in

Figure 4 it can be observed that companies whose decisions focused on compliance with legal obligations and the implementation of economic measures aimed at ensuring business survival presented a discourse of self-protection. The companies whose operational decisions could be considered as ethical practices that entail fair and equitable actions that avoid damage, presented a speech of self-exaltation, highlighting that these actions took place in an uncertain and dangerous environment. Companies that promoted altruistic actions presented discourses without selfish attributions, a communicational approach that would also be characteristic, although to a lesser extent, of companies with commercial CSR practices.

In more detail, focusing on the second quadrant, we found a relationship between the group of companies with commercial strategies and altruistic outlook, both with a notable absence of negative terms in their discourses. In the case of companies with altruistic strategies, they focused on the “solidarity” of their actions, the “encouragement” to continue growing together with this “fight”, and “improve” hand in hand with “innovation”, and we found a relationship with the discourse associated with society (see

Figure 3). Companies with commercial strategies also used a discourse full of positive words, focusing their efforts on “commitment” and the “guarantee” of continuing their activity. They sought the “confidence” of their interest groups through “help”, such as “deferring” quotas or “offers” on payments; in short, providing all the possible “advantages” within their services, safeguarding the “interests” related to products and services.

The discourse of companies with economic and legal decisions was highly similar to that of investors and shareholders. Finally, in the lower half of the figure, we find the terms most used by companies with ethics as their starting point. They sought fair and equitable actions in order to avoid damage, with a discourse focused on doing things well in a hostile environment, starting with “protecting” and promoting a safe workplace, providing all “essential” services, and ending with “sharing” all actions, reflections and ideas that open new “possibilities” to the most “affected” groups. Again, we found extensive similarities to the discourses in relation to the other interest groups; in this case, the group of companies with commercial strategies used a discourse that was slightly similar to those used with customers and suppliers and collaborators (see

Figure 3).

6. Discussion of Results

The joint analysis of the results obtained confirms the expected hypotheses regarding the CEOs’ sentiments, the decisions made and the presence of selfish attributions in their external communications reporting on the situation and consequences of COVID-19. Specifically, selfish attributions are evidenced in management when they make purely economic and legal decisions aimed at guaranteeing the survival of the company based on lay-offs, divestment, etc. In this regard, they incorporate comments that determine the influence that COVID-19 has had, attributing these actions to external factors. These results are in line with those obtained in previous research (i.e., [

79,

80,

82,

85,

90]).

Likewise, those companies that reported on responsible actions related to commitments to employees, customers, suppliers and collaborators linked them to the external negative aspects of the situation caused by the pandemic as a strategy of self-glorification of the manager. In other words, the promotion of action, despite the existence of negative external circumstances for the company, is highlighted.

On the other hand, this work shows the existence of a new strategy in business communication, self-verification. Thus, the speeches of the CEOs who made altruistic decisions, mainly with respect to society, present the company in a position that corresponds to reality, i.e., not becoming a partner in solidarity in the face of a devastating health and economic event. According to the theory of social psychology, self-verification is typical of managers who want to be known and understood by others according to their firm beliefs and feelings about themselves, including their sense of self and self-esteem. Similar results were obtained by Phan et al. [

91], García-Sánchez et al. [

92], Melón-Izco et al. [

93], Capela-Borralho et al. [

94] and Parra-Domínguez et al. [

95], authors who found the existence of a neutral discourse when companies report on their commitments to the 2030 Agenda, the content of management report or a CSR coupling in the case of family firms reporting.

Additionally, we observed differences in the channels used by managers to communicate with stakeholders and convey peace of mind and trust. Thus, for the companies that opted for a speech of self-protection, their communication channel has only been through a crisis declaration letter in which the companies outsource responsibility for the events that have occurred, thereby justifying the need to implement necessary measures to avoid further damage and ensure the image of the company as in control of the situation. The rest of the companies opted for more dynamic and constant communication, mainly focused on updated web content. We observe a greater degree of innovation in companies with a self-evaluating discourse, in which CEOs have used videos or alternative formats to interact with their stakeholders.

7. Conclusions

In this research, we have shown that during the hardest moments of the COVID-19 pandemic, managerial sentiment was reflected in the CEOs’ communications with their stakeholders, informing them about business decisions related to containment vs. expansion, from both an economic and social point of view, which entailed different selfish attributions or patterns of self-verification.

Decisions with a positive sentiment (increased investment, maintenance of jobs, donations, etc.) during the pandemic suggest that the CEO interprets that the company has the resources and capabilities necessary to face external challenges, envisioning opportunities in the midst of the pandemic that they consider to be an expansive strategy. In contrast, the less optimistic CEOs made decisions focused on containing spending through cuts to salaries, lay-offs, etc., as well as those related to the distribution of dividends and paralysis or divestment.

Attributions reflected in speech are the consequence of a process of knowledge through which CEOs confer a certain causal order to current and anticipated events due to COVID-19. Two possibilities are given to explain said events: attribution to internal factors or attribution to external factors. These attributions are classified as selfish when favourable events are accredited to a company’s internal factors, which are controlled by managers, while unfavourable events or decisions are denied and justified/explained by exogenous reasons over which the management is not able to exercise control. An oriented approach tries to separate the news from the management, seeking to protect or repair the image of the company and the management.

Our results show that there is a selfish attribution of news with two patterns: self-exaltation and self-protection. News attribution is self-enhancement because positive decisions are highlighted within a context characterised by negative external circumstances for the company. Self-protection means exonerating negative news by attributing it to external causes and presenting it as efforts made for the general good that would not have been necessary in the event that the event had not occurred.

Additionally, companies’ identification of the stakeholders affected by the COVID-19 pandemic determines their business model and their main stakeholders, thereby specifying the actions to be taken to guarantee their interests. This approach has marked the existence of patterns in the adopted discourse. In this sense, the discourse with investors and shareholders is focused on a transfer of responsibilities, being corrected as the company included additional responsible measures with respect to employees, clients, suppliers and society in general.

Our study makes important contributions to the literature through a novel approach to the analysis of management sentiments and operational and communication decisions made in crisis situations, where emotional response can be a key factor in the success of these strategies. Thus, we evidence the importance that executives’ communication and the level of feeling have at a strategic and relational level, highlighting the importance of cognitive levels to give meaning to the decisions made and their effectiveness in relation to problems and challenges to address. In addition, we expand the current research on sentiment analysis and business decisions in a context of unknown crisis and with implications not only economic, but also health and social. In this sense, the CEO’s sentiment in the decisions made is unquestionable, being aggravated by the economic conditions the company faces. Thus, from a theoretical point of view, our findings suggest the role that contextual variables associated with external events play and the implications they have on business decisions based on the CEO’s sentiment are mainly determined by the CEO’s optimism and degree of innovation.

From a practical point of view, we provide evidence of communication strategies that allow external users—investors, employees, etc.—to determine the optimism or pessimism of the management from the sentiment in the communications and the presence of selfish attributions. Likewise, we identify the existence of similar patterns in the frequency and communication channel used, being less dynamic and innovative in those companies that make decisions that represent a brake on the strategies and planned actions.

The results obtained are subject to a set of limitations that must be considered in future studies, especially those referring to the cultural bias of a country, as the evidence obtained is specific only to similar institutional settings. According to social psychology, leadership and culture are two interrelated concepts due to cultural factors’ influence on psychological and organizational processes. Considering that culture comprises a set of beliefs, attitudes, values and practices shared by a group of individuals, Spanish CEOs share a common history and interact in an identical social structure, making decisions that do not necessarily have to coincide with those they would make their counterparts in other cultural settings. In this sense, carrying out cross-cultural comparisons would allow the validation of the evidence in this research.

Finally, future researches should focus on the role that different public actors, including academics, play in these difficult times for society. The evidence obtained in this paper has parallels with the arguments of Jasanof (2003) and Funtowicz and Ravetz (2008), focused on addressing the challenges of replacing “technologies of arrogance” with “technologies of humility”. Thus, just as CEOs make decisions aimed at a sustainable business model that favours the growth of companies and is a guarantee of social well-being, public actors and researchers must correct, among other aspects, the “peripheral blindness to uncertainty and ambiguity” and “limited capacities to internalize the challenges that arise in uncertain contexts”, among other aspects. In so doing, they are taking a stance favouring “framing” issues so that essential questions—purpose, who is affected, who benefits—come to the fore. Researchers must replace the concept of the human being as a passive subject of a supposedly homogeneous society with active members that correct differences in power, access, vulnerability and other inequalities that affect the quality of life, all of this, taking into consideration different points of view.