Social Sustainability through Children’s Expressions of Belonging in Peer Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

Previous Research

- How do children create and express peer communities during free play?

- What do the children gather around in these communities?

- How do these communities create boundaries, and what conditions do they set for children’s belonging?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Social Sustainability

2.2. Communities

2.3. Belonging

2.4. Politics of Belonging

2.5. Situated Intersectionality

2.5.1. Social Positions

2.5.2. Identification with and Emotional Connection to Various Communities

2.5.3. Ethical and Political Values to Which Children Relate

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Emotionally Tight Communities

The School Game

In the middle of the room is a large sofa. A lot of activities are going on in the large room in the preschool department. Mari and Geir are sitting on the sofa. The adults sit at different tables spread out across the room. Several groupings of children are spread out across the room, playing. The children move back and forth between the tables and other activities. In between the two children on the sofa there is a backpack, some books, and a teddy bear. The children are focusing on each other; they talk, they look at each other, they mirror each other’s initiatives playing with the sack. The other children approach them, sometimes taking a seat on the sofa, sometimes just stopping and watching them, and then leave to play elsewhere. Mari and Geir seem not to register the other children. They are totally absorbed in each other, building up their play, eagerly chatting with each other (inaudibly).

After a while, Mari initiates putting the toys in the sack. ‘I can pack’, she says. Quickly, she puts the teddy bear and some books in the bag. ‘Yes, these are your homework’, confirms Geir, with a supporting tone of voice, while he also put books in the backpack. Geir looks at the sack. ‘I can help you to put it on’, he says. He lifts the backpack and places it on Mari’s back. Then he crawls down from the sofa, sits close beside her, and fastens a strap around her body. ‘I can accompany you to school’, he says, friendly. ‘Yes’, says Mari and smiles. Together they walk across the room. Eventually they stop to adjust the backpack and the straps, helping each other.

Now Mari closes her eyes and turns her face towards the ceiling (acting as though she cannot see). ‘I can accompany you, so you don’t have to walk (alone?)’ says Geir. He grabs a strap of the backpack and leads her across the floor. Mari takes his hand. They walk hand in hand into the locker room. There is no one there. Playfully, they tease each other, throwing drawing papers, holding and pulling each other while laughing.

When another child Judith enters the locker room and asks if she can join, Mari quickly turns around towards her, saying firmly, ‘no, we are playing the school game’, and quickly turns back towards Geir. Judith quickly leaves the locker room. After a while, Mari says: ‘Let’s go home’. ‘Yes’, Geir responds. ‘School has ended now’, he continues. The children continue to playfully pull each other and laugh while moving out of the locker room. Entering the large room, they are encountered by an educator asking them if they denied Judith joining in their play. ‘We said yes’, Mari and Geir respond quickly. ‘You did not listen to us’, continues Geir, looking at Judith. Now the educator offers some suggestions for playing together, but the children do not accept these. ‘We are playing the school game’, says Geir in a low tone of voice, looking down at the floor. Mari and Geir stand still and quiet for a while. Then they walk close together, away from the sofa. Judith remains sitting on the sofa looking in a book.

4.2. Communities Based on Norms and Power Struggles

Jumping from the Wall Bar

It is playtime in preschool. Iselin is standing in the middle of the room looking at the activities going on between the children. An educator asks Iselin if she wants to join her in the sports room (a large room with cushions, mattresses, and climbing walls). Iselin nods, confirming. She smiles a little. When the door is opened by the educator, all the children quickly spread out. Some children run to some large mattresses and a climbing house. Dimitri is first to the house and he fetches a large cushion, looking (surprised) at the other children running towards him. Other children join; some enter the house, others search for cushions. Dimitri picks up the cushion, walks over to the educator, and lies down beside her, observing the other children enthusiastically building a house.

Now the educator initiates a jumping activity from a wall bar, which immediately catches the attention of several children. The educator informs the children when to jump and that they need to queue in a line. She encourages them: ‘You are indeed skillful’. The play is intense and there is a lot of noise, screaming, and laughter in the room.

Iselin is standing still on the floor, watching. Now the educator invites Iselin to join. Iselin takes a position at the end of the queue of eight children. She stands quietly waiting for her turn. There is noise and distress in the queue. The children do not agree on how to play, they push each other, blame each other for “sneaking” into the queue, they hit each other. Iselin looks gently over her shoulder. She climbs a few steps up the bar and then down again; thereafter she jumps down on the mattress. She walks away from the bar and stops, looking at the children in the queue. Conflicts still appear around how to jump, and some of the children leave the queue and return to building the house. Iselin jumps a little by herself on a small mattress beside her. Later, she sits down on the educator’s knee. Dimitri is lying on a cushion beside the educators. Iselin and Dimitri look at the other children jumping. After a while Dimitri leaves the sports room. /.../ After 30 min the educator says that it is cleaning up time.

4.3. Communities of Open Borders and Joyfulness

No Walking in the Lava

Dimitri, Stefan, and Mina are in the sports room with an adult. Mina runs around, jumping on the mattresses. Stefan and Dimitri are building a tower with cushions, following the educator’s initiative. After a while, Mari and Geir enter the room. Dimitri observes them, silent, and then lies down on a mattress.

Geir starts to walk around on the mattresses, which are spread out on the floor in a circle. Mari quickly follows and says, smiling, ‘shall we play don’t step on the lava, Geir?’ Geir says ‘yes’ with a happy tone of voice. He starts running on the mattresses, trying to avoid touching the floor. Mari follows, laughing. After a while, Stefan, Jon, and Dimitri run around on the mattresses following the same pattern. Mina and Charlotte are now in the room and they join the activity. Now and then, Mari and Geir instruct their peers on how to run and how the mattresses should be ordered. Now, all the children in the sports room join the activity. Eventually they stop, sit down for a while, and then start running again.

From the CD player, one can hear music (A song “The Rescue Boat Elias”). After a few running rounds, Jon stops by the CD player and skips to another song, which results in a loud sound. Jon and the children look at each other and they all start to laugh. Jon continues to play; he runs, stops by the CD player, and turns up the sound. The children look at each other, laughing. Jon repeats the play. Sometimes he turns up the volume. Other times, he skips to another song. The children look at him and laugh. The adult tries many times to make Jon stop, but he ignores her. After a while, she turns off the CD player. The children continue running on the mattresses, eagerly trying not to step in the “lava”. After 10 min, the play is interrupted by some children running into the room with paper airplanes in their hands.

5. Discussion

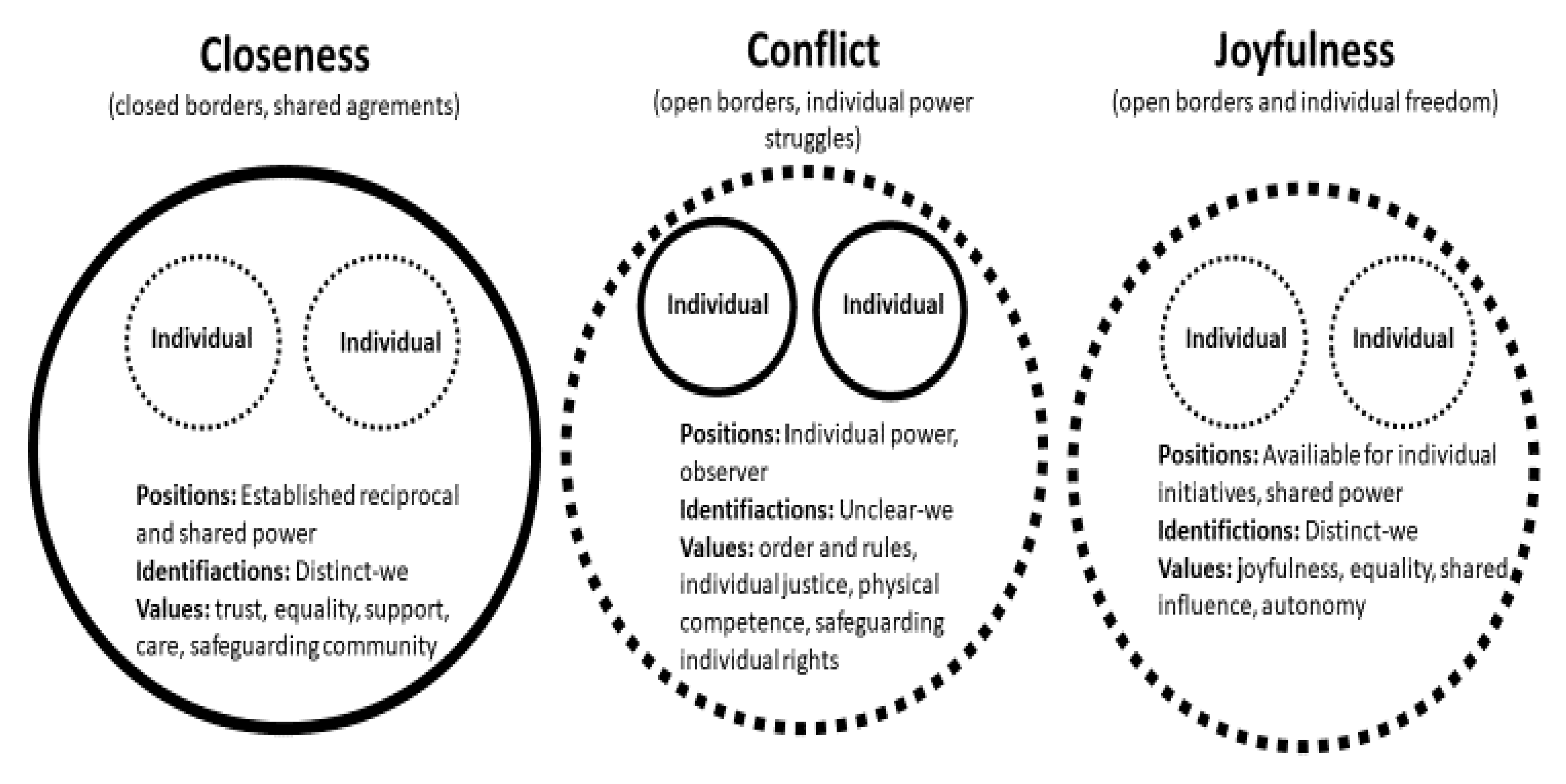

5.1. Communities of Closeness, Conflicts, and Joyfulness

5.1.1. Communities of Closeness

5.1.2. Communities of Conflict

5.1.3. Communities of Joyfulness

5.2. Social Sustainability: Safeguarding the Individual and the Community

6. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuval-Davis, N. The Politics of Belonging: Intersectional Contestations; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- SSB. Barnehager, Antall Barn i Barnehager 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/statistikker/barnehager (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Ministry of Education and Research. The Kindergarten Act; Ministry of Education and Research: Oslo, Norway, 2000.

- Ministry of Education and Research. The Framework Plan for the Content and Tasks of Kindergartens; Ministry of Education and Research: Oslo, Norway, 2017.

- UN Convention. The UN Convention of the Right of the Child; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Pramling, N.; Samuelsson, I.P. Introduction and frame of the book. In Educational Encounters: Nordic Studies in Early Childhood Didactics; Pramling, N., Samuelsson, I., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Boldermo, S.; Ødegaard, E.E. What about the migrant children? The state-of-the-art in research claiming social sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, S. Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions; Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Berge, A.; Johansson, E. The politics of belonging: Educators’ interpretations of communities, positions, and borders in preschool. J. Int. Res. Early Child. Educ. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- May, V. Connecting Self to Society. Belonging in a Changing World; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mahar, A.L.; Cobigo, V.; Stuart, H. Conceptualizing belonging. Disabil. Rehab. 2012, 35, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juutinen, J.; Puroila, A.-M.; Johansson, E. “There is no room for you!” The politics of belonging in children’s play situations. In Values Education in Early Childhood Settings: Concepts, Approaches and Practices; Johansson, E., Emilson, A., Puroila, A.-M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Hännikäinen, M. Creating togetherness and building a preschool community of learners: The role of play and games. In Several Perspectives in Children’s Play. Scientific Reflections for Practitioners; Jambor, T., Van Gils, J., Eds.; Garant Antwerpen: Apeldoorn, Belgium, 2007; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Juutinen, J. Inside or Outside? The Small Stories about the Politics of Belonging; University of Oulu: Oulu, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Puroila, A.-M.; Emilson, A.; Palmadottir, H.; Piskur, B.; Tofteland, B. Educators’ interpretations of children’s belonging across borders: Thinking and talking with an image. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2021. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Press, F.; Worow, C.; Logan, H.; Michel, L. Can we belong in a neo-liberal world? Neo-liberalism in early childhood education and care policy in Australia and New Zealand. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2018, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjora, A. Hva er Fellesskap; Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, E.; de Haan, D. The Social Lives of Young Children; SWP Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, U. Togetherness and diversity in pre-school play. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2001, 2, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Mortlock, D. Finding the most distant quasars using Bayesian selection methods. Stat. Sci. 2014, 29, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Emilson, A.; Johansson, E. Values in Nordic early childhood education—Democracy and the child’s perspective. In International Handbook on Early Childhood Education and Development; Fleer, M., van Oers, B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 929–954. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, E.; Berthelsen, D. The birthday cake: Social relations and professional practices around mealtimes with Toddlers in childcare. In Lived Spaces of Infant-Toddler Education and Care. Exploring Diverse Perspectives on Theory, Research and Practice; Harrison, L., Sumsion, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 75–88. ISBN 978-94-017-8837-3. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. Playing with difference: The cultural politics of childhood belonging. Int. J. Divers. Organ. Commun. Nations Annu. Rev. 2007, 7, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Richardson, C. Home renovations, border protection and the hard work of belonging. J. Aus. Res. Early Child. Educ. 2005, 12, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbeck, M.; Yim, H.Y.B.; Lee, L.W.M. Belonging, being, and becoming: Challenges for children in transition. Diaspora Indig. Minor. Educ. 2010, 4, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachrisen, B. Like Muligheter I Lek? Interetniske Møter I Barnehagen (Equal Opportunities in Play? Interethnic Encounters in ECEC); Universitetsforlaget: Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Macartney, B.C. Teaching through an ethics of belonging, care and obligation as a critical approach to transforming education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2012, 16, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juutinen, J.; Kess, R. Educators’ narratives about belonging and diversity in northern Finland early childhood education. Educ. North 2019, 26, 2. Available online: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/eitn37 (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Siraj-Blatchford, J. Editorial: Education for sustainable development in early childhood. Int. J. Early Child. 2009, 41, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, P. Världsmedborgaren. Politisk Och Pedagogisk Filosofi För Det 21 Århundradet [The World-Citizen. Political and Educational Philosophy in the 21st Decade]; Daidalos: Göteborg, Sweden, 2005. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, E. The preschool child of today—The world citizen of tomorrow; Int. J. Early Child. 2009, 2, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägglund, S.; Johansson, E. Belonging, value conflicts and children’s rights in learning for sustainability in early childhood. In Research in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: International Perspectives and Provocations; Davis, J.E., Elliot, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, E. Foreword. In Researching Early Childhood Education for Sustainability. Challenging assumptions and Orthodoxies; Elliott, S., Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E., Davis, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ärlemalm-Hagsér, E.E. Engagerade i Världens Bästa? Lärande för Hållbarhet i Förskolan. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Education, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Björneloo, I. Innebörder Av Hållbar Utveckling. En Studie Av Lärares Utsagor OM Undervisning [Meanings of Sustainable Development. A Study of Teachers’ Statements on Their Education]. Ph.D. Thesis, Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis, Göteborg, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, B.; Choy, G.; Lee, A. Harmony as the basis for education for sustainable development: A case example of Yew Chung International Schools. Int. J. Early Child. 2009, 41, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjora, A.; Scambler, G. Communal Forms. A Sociological Exploration of Concepts of Community; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cripps, E. Collectivities without intention. J. Soc. Philos. 2011, 42, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, C. School exclusion: The will to punish. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2005, 53, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuval-Davis, N.; Wemyss, G.; Cassidy, K. Bordering; Polity Press: Medford, OR, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Probyn, E. Outside Belongings; Routledge: New Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley, M.; Berry, H.L. Longing to Belong: Personal Social Capital and Psychological Distress in an Australian Coastal Region. SSRN Electron. J. FaHCSIA Social Policy Research Paper No. 39, March 1 2010, FaHCSIA Social Policy Research Paper No. 39. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1703238 (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Sumsion, J.; Wong, S. Interrogating ‘belonging’ in belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2011, 12, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E.; Emilson, A.; Puroila, A.-M. Mapping the field: What are values and values education about? In Values education in Early Childhood Settings. Concepts, Approaches and Practices; Johansson, E., Emilson, A., Puroila, A.-M., Eds.; Springer: Cham Switzerland, 2018; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ricoeur, P.; Thompson, J.B. The model of the text: Meaningful action considered as a text. Hermeneut. Hum. Sci. 1981, 38, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, E. Toddler’s relationships: A matter of sharing worlds. In Studying Babies and Toddlers: Cultural Worlds and Transitory Relationship; Li, L., Quinones, G., Ridgway, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Greve, A. Vennskap Mellom Små Barn i Barnehagen (Friendship between the Youngest Children in Kindergarten). Ph.D. Thesis, Unipub Forlag, Oslo, Norway, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rosell, Y. Møter Mellom Barn-Kontinuitet, Dissonans Og Brudd I Kommunikasjonen (Encounters between Children—Continuity, Dissonans and Discontinuity in Communication). Ph.D. Thesis, Det Humanistiske Fakultet, Universitetet i Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, C. Belonging. In A Companion to Social Geography; Del Casino, V.J., Jr., Thomas, M.E., Cloke, P., Panelli, R., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2011; pp. 108–124. [Google Scholar]

- Selby, J.M.; Bradley, B.S.; Sumsion, J.; Stapleton, M.; Harrison, L.J. Is infant belonging observable? A path through the maze. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2018, 19, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigos, T.; Bradley, B.; Sumsion, J. Infants, family day care and the politics of belonging. Int. J. Early Child. 2014, 46, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ree, M. Vilkår for Barns Medvirkning i Felleskap i Barnehagen. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitetet i Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tofteland, B. Måltidet i Barnehagen: Demokratiets Vugge [Analysing Conversations with Educators in Preschools. The Meal in Preschool: The Cradle of Democracy]. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitetet i Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, E.; Emilson, A. Conflicts and resistance: Potentials for democracy learning in preschool. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2016, 24, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Johansson, E.; Rosell, Y. Social Sustainability through Children’s Expressions of Belonging in Peer Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073839

Johansson E, Rosell Y. Social Sustainability through Children’s Expressions of Belonging in Peer Communities. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073839

Chicago/Turabian StyleJohansson, Eva, and Yngve Rosell. 2021. "Social Sustainability through Children’s Expressions of Belonging in Peer Communities" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073839

APA StyleJohansson, E., & Rosell, Y. (2021). Social Sustainability through Children’s Expressions of Belonging in Peer Communities. Sustainability, 13(7), 3839. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073839