Abstract

The happy-productive worker thesis (HPWT) is considered the Holy Grail of management research, and it proposes caeteris paribus, happy workers show higher performance than their unhappy counterparts. However, eudaimonic well-being in the relationship between happiness and performance has been understudied. This paper provides a systematized review of empirical evidence in order to make a theoretical contribution to the happy-productive worker thesis from a eudaimonic perspective. Our review covers 105 quantitative studies and 188 relationships between eudaimonic well-being and performance. Results reveal that analyzing the eudaimonic facet of well-being provides general support for the HPWT and a much more comprehensive understanding of how it has been studied. However, some gaps and nuances are identified and discussed, opening up challenging avenues for future empirical research to clarify important questions about the relationship between happiness and performance in organizations.

1. Introduction

The happy-productive worker thesis (HPWT) has been the Holy Grail of management and organizational psychology research for decades [1,2]. This thesis states that all things being equal, happy workers perform better than those who are less happy [2]. Regardless of the apparent intuitiveness of this idea, the well-being–performance link is still not clear, and debate between its defenders and more skeptical views has been always present [3,4,5]. In fact, four decades of research in this area have produced large amounts of empirical evidence, sometimes with unexpected results. For example, Peiró, Kozusznik, Rodríguez, and Tordera [6] warned about an oversimplification that has tended to highlight the positive relationships and neglect the negative or null ones in the research on the HPWT. Other issues might also be hampering the understanding of the well-being–performance link, such as the assumed direction of the relationship, where well-being is the antecedent of performance, or a noteworthy bias in the conceptualization of well-being in organizational research, with an overwhelming focus on hedonism to the detriment of eudaimonia [7,8]. A deeper focus on eudaimonic well-being (EWB), which refers to the ideal in the sense of excellence giving meaning and direction to life [9], is necessary in order to more fully understand the relationship between happiness and productivity [10,11]. In addition, the concept of eudaimonia entails different facets that encompass distinct ways of behaving and feeling [12]. However, these ways of behaving and feeling involve a series of common themes (e.g., excellence, engagement, development, meaning, contemplation, etc.) with nuances (e.g., present- vs. future-oriented), and they have received differential attention in the research. This abundant research posed the risk of producing a new imbalance, this time within the eudaimonic facet of the HPWT, by focusing on certain indicators of EWB and neglecting others. This emphasis limits the understanding, theoretical advancement, and validity of the HPWT, and it represents a weakness in the attempts to promote happiness (hereinafter, also well-being) and performance in organizations in a beneficial way for employees and employers.

Thus, there is a need for a more comprehensive study of the eudaimonic well-being–performance relationships that can more accurately capture the complexity of these phenomena. It is important to consider the different facets of the eudaimonic construct of well-being and the theoretical backgrounds of their relationships with different types of performance, without neglecting the possible negative or null results obtained when testing the HPWT in this area and their implications. Another issue that has created considerable debate is the directionality of the well-being–performance causal relationships [11]. Although the traditional research trend has almost exclusively examined the happiness–performance relationships in this sequence, it has been suggested that these links may also have the reverse direction (performance-happiness) or even a reciprocal or spiral relationship over time. This might be especially relevant in the case of EWB because eudaimonia is inherently dynamic and implies a sense of personal development, growth, and full functioning, in which an individual’s job performance is likely to play an important role.

Therefore, this study holds the promise of important theoretical implications as it aims at improving the understanding and efforts to promote happiness and performance in organizations in two ways. First, focusing on the eudaimonic side of well-being, we provide a systematic review of the empirical studies on the relationships between happiness and performance in the frame of the HPWT and their theoretical bases, empirical contributions, and potentially relevant nuances. Second, we discuss the main gaps identified and propose a future research agenda for fully incorporating EWB into HPWT research. Thus, we aim to enrich the knowledge and create new avenues for empirical research that should contribute to clarifying important questions about the complex relationships between happiness and productivity in organizations and help to promote them in the future.

1.1. Conceptualization of Eudaimonic Well-Being

Research on well-being has increased considerably in recent decades in fields such as management or organizational psychology [13,14]. The field of well-being has basically been organized in two traditions [15]: hedonic and EWB. Hedonic well-being is conceived as the experience of pleasure and positive affect [16]; hence, people seek happiness through pleasure attainment and pain avoidance [17]. In the context of work and organizational research, this hedonic view has given a protagonist role to concepts such as positive/negative affect and, especially, job satisfaction, as happiness indicators. However, well-being at work is more than job satisfaction, emotions, and affects [18]. As Warr [19,20] pointed out, eudaimonic approaches tend to emphasize optimal human functioning rather than the affective elements that characterize hedonism. Eudaimonia focuses on meaning and self-realization. Specifically, EWB has been defined as the ideal in the sense of excellence, a perfectionistic idea toward which one strives, giving meaning and direction to life [9]. Thus, this perspective goes beyond mere positive-affect and satisfaction experiences to focus instead on a sense of meaning, identity, and self-realization that people can obtain by identifying their virtues and cultivating them [21] in different life areas. Eudaimonia is also characterized as the person’s engagement in the world (“aspiration”), feeling able to achieve personally important goals (“competence”), being able to influence one’s life (“autonomy”), and having vitality and interacting positively with other people [19,22,23,24].

Applied to the work domain, the eudaimonic perspective has given rise to happiness indicators that are different in nature from those traditionally considered by the dominant hedonistic view of occupational well-being. Nevertheless, this does not mean that eudaimonically happy people are not hedonically happy; in other words, the two perspectives are not opposite ends of a continuum per se, but rather two different ways of achieving a double sense of happiness [25,26] that may or may not be related [27]. In fact, the imbalance between hedonic and eudaimonic studies represents an important gap in the research on the HPWT, which has tested the different issues related to its main principle (i.e., happy workers perform better than unhappy ones) in studies that have focused excessively on hedonia and neglected eudaimonia [8,11]. In contemporary western society, pleasure is undoubtedly a component of happiness, but other aspects are also important in considering one’s life a full life [27].

Recently, the eudaimonic view has gained a presence in the organizational literature, and a number of issues have been analyzed while new research questions have emerged that deserve further attention in the HPWT framework. Understanding EWB in the HPWT framework calls for its proper conceptualization and the consideration of its complexity and broadness. There have been various conceptions of eudaimonia provided by different authors over the years (or even centuries) (see [12] for a review). Ancient Greek philosophers first presented the concept as an active behavior that is performed for its own sake, and that exhibits excellence and virtue in accordance with reason and contemplation [21]. This conceptualization has been more or less explicitly adopted by some of the most influential names in modern psychology and psychiatry. For instance, Maslow’s [28] concept of self-actualization refers to a natural human need to strive for higher levels in life and become all that one can be. Self-actualized individuals usually show features such as openness to challenge, autonomy, awareness, acceptance of, connection with, and appreciation for life experiences, oneself, others, and the surrounding world, or feeling alive. Other theorists have referred to individuation [29], psychological well-being [30], or full functioning [31], which express similar ideas.

Nevertheless, most of the empirical research on EWB has been performed since the second half of the 20th century, and it has led to diverse operationalizations of the concept. One fruitful component to structure these approaches is their time orientation. Whereas some facets of eudaimonia focus on the fulfilling experience in the present moment, others refer to one’s identity and purposes with a clear projection towards the future. In the first group (i.e., present-oriented aspect of eudaimonic well-being), we include concepts that focus on well-being and self-fulfilling experiences in the present, such as full immersion in activities and deployment of one’s capacities as a way of finding happiness. Among these concepts, we include flow [32], which refers to an optimal state experienced when a person skillfully engages in challenging activities so intensely that nothing else seems to matter and even the notion of time is lost. We also include engagement as a fulfilling state of connection with work, characterized by vigor, absorption, and dedication, as conceptualized by Bakker, Schaufeli, and others [33]. Interestingly, engagement was originally conceptualized by Kahn [34] as the investment of one’s complete self in a (work) role in terms of emotional, cognitive, and physical energies and identity, that is, a future-oriented type of eudaimonic construct. This second group (i.e., future-oriented aspect of eudaimonic well-being) includes concepts such as psychological well-being [9], which has probably been the most recurrent view of eudaimonia until today, due to its widely used measurement scale, which includes the six dimensions of personal growth, purpose in life, autonomy, environmental mastery, positive relations, and self-acceptance. Other future-oriented EWB concepts such as personal expressiveness [35] or meaning in life [36] refer to a range of evaluations and orientations about one’s actions and activities and the extent to which they are representative of one’s identity, needs, and purpose. Similarly, Huta and Ryan [37] defined eudaimonia as a motive for seeking and developing the best of oneself in one’s activities. Thus, what this group of EWB views has in common is its special focus on aspects such as growth, development, purpose, and meaning, which represent the sense of an individual’s activities in connection with his or her identity, forged in the past, enacted in the present, but mainly open towards the future.

Together, these conceptions reflect a person-centered approach [38] that considers the individual as a living integrated whole, tending to goals, interacting with the surrounding world, with feelings lived through experience and oriented toward the future [39]. From this perspective, eudaimonic well-being is strongly related to the extent to which the work domain allows and helps the individual to find and strive for purpose and meaning (work- and life-related), impact the surrounding world, experience life, and develop his or her identity and personality. Thus, EWB at work is a complex phenomenon that entails a number of facets with many different nuances, such as a variety of ways of feeling and behaving with different degrees of orientation toward the present or the future.

At this point, we can ask ourselves whether research on the HPWT has considered and contributed to theoretical advancements that take EWB’s richness and complexity into account. In other words, a relevant issue is the extent to which the empirical research on the HPWT has used operationalizations and theoretical foundations to capture and explain the inherent complexity of EWB and, by extension, its relationships with performance. For instance, the literature has paid more attention to eudaimonic constructs such as work engagement or flow, which represent the full investment of one’s capacities and energies in work, with a predominant focus on the present. Nevertheless, research has focused less on other indicators of EWB that represent striving for meaning, the broad scope of concern, or personal growth and development, which involve a deep connection with one’s identity and a projection into the future. This gap has important implications for the HPWT because relevant aspects of the eudaimonic spectrum are hardly considered in trying to better understand performance. In this sense, the relationship between the eudaimonic facet of happiness and performance (and their theoretical explanations) stemming from the drive towards long-lasting purpose, meaning, and self-development may differ from the relationships derived from eudaimonic well-being based on momentary fulfilling immersion in one’s work activity (i.e., flow, engagement).

1.2. Work Performance and Its Facets

Despite the rapid growth in research on eudaimonia since the beginning of the 21st century, research on the well-being–performance relationship using this conceptualization is still limited, compared to the hedonic perspectives [10,11]. Nevertheless, the many studies carried out to date deserve an integrated review that summarizes the main achievements and identifies relevant gaps and issues for the future research agenda. A better understanding of the eudaimonic perspective of well-being would not only provide a more comprehensive view of the well-being construct itself, but it may also be relevant for identifying significant new links between well-being and performance. However, it also requires a more detailed consideration of performance [40].

Employee work performance has been defined as “a function of a person’s behavior and the extent to which that behavior helps an organization to reach its goals” [41] (p. 187) or as “the total expected value to the organization of the discrete behavioral episodes that an individual carries out over a standard period of time” [42] (p. 92). In terms of behavior, a distinction has been made between four broad dimensions of employee performance [41]. Task or in-role performance refers to the activities included in the job description, and it is defined as “the total expected value of an individual’s behaviors over a standard period of time for the production of organizational goods and services” [42] (p. 106). Contextual or extra-role performance refers to behaviors that are not considered in job descriptions, and it is defined as “behaviors that support the organizational, social, or psychological environment in which the technical core functions” [40] (p. 861). Creative performance is defined as the behaviors that express employees’ creativity through novel ideas, procedures, or products that are beneficial for the organization [40,43]. Finally, counterproductive behaviors are behaviors that harm the functioning of the organization [40], such as absenteeism, theft, or substance abuse. In addition, global (global performance) or composite indicators of performance include varied performance measures together in one global measure or two or more types of performance in a composite score.

Given the variety of performance and EBW indicators, an initial relevant research question arises about their empirical relationships, in order to better understand their sign and meaning when analyzing relationships between specific indicators of each of them, the extent to which they support the HPWT, and how they can be fruitful for people and organizations.

RQ1. What is the empirical evidence about the relationship between EWB and performance used in HPWT research when differentiating the specific dimensions of both constructs?

Moreover, some gaps have been pointed out in the research on the HPWT regarding the directionality of these relationships [11]. Most of the research has assumed that well-being is an antecedent or cause of performance (see [10] for a review). Nonetheless, alternative perspectives of the HPWT have also been considered, pointing out that the direction of these links can also be reversed (i.e., work can enhance employees’ EWB [44] or reciprocal (well-being causes performance, and performance causes well-being) [11]. Mutual and dynamic relationships between well-being and performance would imply a synergy leading to a virtuous (or vicious) cycle over time, where higher (or lower) performance leads to higher (or lower) levels of EWB and, in turn, to higher (or lower) performance, and so on. Obviously, this process might have potential benefits (or disadvantages) for both the employee and the organization.

Therefore, to fully understand the role of EWB in the HPWT, research should incorporate its dynamism into its study. However, dynamism is an aspect that research, in general, tends to overlook because its analysis requires the use of high-resource research methods (e.g., longitudinal designs). With all this in mind, we formulate the following research question:

RQ2. What is the empirical evidence about the (bi)directionality of the relationship between EWB and performance in the framework of the HPWT?

Finally, another aspect that has attracted interest involves better understanding of the theoretical grounds and mechanisms that may help to predict and explain the relationships between EWB and different types of performance. Are they common to different types of EWB constructs and performance indicators, or are they specific to different well-being experiences and performance facets? If there are differences, what do they mean? Understanding the theoretical grounds of the EWB–performance links is necessary for knowledge generation and theoretical advancement related to the HPWT. Therefore, we formulate our last research question:

RQ3: What are the main theories that have supported the empirical research on the relationships between EWB constructs and different performance types?

Thus, this paper aims to offer a systematic review of the EWB–performance relationship, in order to provide an overview of the empirical and theoretical advances in the research on the eudaimonic facet of the HPWT and answer some emerging questions about this thesis. Moreover, we aim to detect and discuss some of the main gaps in the literature reviewed and propose a future research agenda to fully incorporate EWB into the research on the HPWT.

2. Materials and Methods

In order to review the empirical evidence on the eudaimonic side of the HPWT, we performed a systematic search following the PRISMA protocol for systematic reviews [45]. We focused on two of the most relevant online databases: ProQuest and PsycINFO. The research team conducted the four main stages of the search in September 2020, with a time scope from 2001 to 2020. In the first stage, a search was initiated that included the following parameters:

ti((Happiness OR well-being OR well-being OR job satisfaction OR positive emotions OR affective well-being OR mood OR pleasure OR happy OR psychological well-being OR engagement OR flourishing OR flow OR unhappy OR purpose OR meaning OR positive affect OR negative affect OR enthusiasm OR worthwhileness OR hedonic OR eudaimonic OR exhaustion) AND (performance OR productivity OR creativity OR efficiency OR effectiveness OR in-role OR extra-role OR OCB OR creative OR organizational citizenship behavior OR prosocial behavior OR counterproductive OR effort OR customer satisfaction OR work facilitation OR innovative OR innovativeness innovation)) AND ab((Occupational OR work OR employee OR job OR staff OR personnel OR workplace OR workforce OR organization OR organisation OR companies OR company OR firm OR industry) AND (Research OR sample OR results OR participants OR subjects))

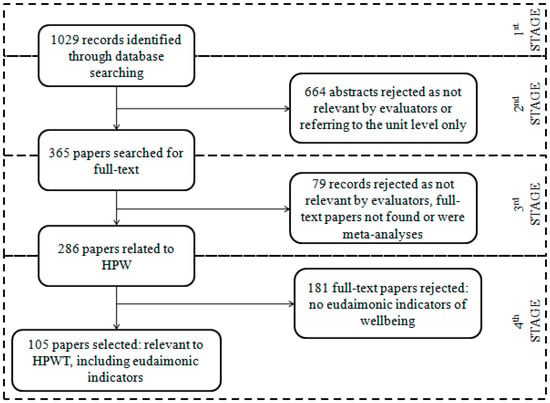

The search yielded 1029 abstracts. In the second stage, two independent evaluators analyzed the abstracts based on the following inclusion criteria: (a) the abstract had to mention that an empirical research study was reported in the paper; (b) the abstract had to mention well-being and performance measurements. Moreover, we included an exclusion criterion: abstracts that mentioned non-employee samples and those that did not mention individual-level measures of well-being and/or performance were discarded. This second stage resulted in 365 abstracts.

Third, we searched for the full-text version of the titles selected. After this process, we discarded 79 titles for the following reasons: they were not considered relevant for the purposes of this review (focused on the well-being–performance relationship); they did not fit the aforementioned inclusion and/or exclusion criteria; the full-text version was not available; or they were meta-analytic studies. At this point, 286 papers were selected for the final (fourth) step: the papers had to include measures of eudaimonic well-being. Finally, 181 papers were discarded because they did not report any eudaimonic measures of well-being, resulting in 105 full papers selected for the review. Figure 1 presents an overview of the analysis and selection process.

Figure 1.

Overview of the search, analysis, and selection process.

Description of the Selected Studies

A number of the 105 empirical studies selected were published in psychology business-, applied-, and management-focused journals, such as the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, or Journal of Organizational Behavior. Regarding performance conceptualizations, the 105 selected publications reported data on 188 relationships between well-being and performance (See Table S1). Of them, 57 (30.32%) relationships involved task performance, 65 (34.57%) contextual performance, 27 (14.36%) creative performance, 10 (5.32%) counterproductive performance, and 29 (15.43%) global performance.

3. Results

3.1. Empirical Evidence on EWB–Performance Relationships in the HPWT

The relationships between EWB and performance found in our studies are presented in Table 1. There is a predominance of significant positive relationships (163 relationships, 86.70%) between EWB and performance, whereas the rest are mostly non-significant (22 relationships, 11.70%), and only three show a significant negative relationship (1.60%). Breaking these figures down into the different performance indicators, there is a clear prevalence of positive relationships involving contextual performance (58 relationships, 30.85%), followed by task (47 relationships, 25%), creative (25 relationships, 13.30%), and global performance (24 relationships, 12.77%), whereas EWB–counterproductive performance negative relationships (9 relationships, 4.79%) supporting the HPWT have been studied less. Furthermore, of the 25 relationships that were not positive (22 were non-significant), eight were with task performance (32%), six with contextual performance (24%), five with global performance (20%), two with creative performance (8%), and one with counterproductive performance (4%). The only three significant negative relationships involved task (2 relationships, 8%) and contextual performance (1 relationship, 4%).

Table 1.

Summary of EWB–performance relationships.

In order to better understand the nature of the relationships found, it is important to consider the different constructs and operationalizations of EWB included in the studies (Figure 2). Table 2 offers a detailed analysis of the relationships found, broken down into the different eudaimonic constructs of well-being and the performance indicators involved, thus revealing the state of the art in the research on the HPWT from a eudaimonic perspective. Based on our distinction, we found that the conceptualizations of EWB either focused more on the present (e.g., flow and job passion) or on the future (e.g., meaning of work, job involvement, flourishing or psychological well-being, calling and purpose), thus representing different aspects of the eudaimonic spectrum: a state of enjoyment of work vs. a projection of the preferred aspects of one’s goals, identity, virtues, and values. A special case is work engagement, which has been conceptualized from two main perspectives, one more present-oriented and the other more future-oriented.

Figure 2.

Eudaimonic well-being conceptualizations.

Table 2.

Summary of EWB–performance relationships considering the different EWB constructs found.

3.1.1. EWB Present-Oriented Conceptualizations.

EWB as Flow. Flow has been defined as a particular experience that is so enjoyable that it is worth doing for its own sake [32]. In the organizational context, it has been defined as a holistic sensation characterized by absorption, work enjoyment, and intrinsic work motivation [46]. Although some authors describe the flow experience as a close variant of positive effect [47], a large number of recent studies describe flow as a momentary form of eudaimonic well-being [48,49,50,51], mainly because it has been shown that people can experience flow even without describing it as pleasant [32]. In the present systematic review, we found a total of seven relationships, six of them describing significant and positive links between flow and task (three relationships), contextual (one relationship), and creative (two relationships) performance, and one non-significant relationship with contextual performance, mostly providing support for the happy-productive worker thesis.

EWB as Job Passion. Vallerand and Houlfort [52] briefly defined passion at work as a strong inclination towards an activity that people like, find important, and invest time and energy in performing. Ho, Wong, and Lee [49] (p.28) conceptualize it as “a job attitude comprising both affective and cognitive elements that embody the strong inclination that one has towards one’s job”. Therefore, the concept of passion highlights a strong, affective liking and enjoyment of the job and its perceived importance to the individual, in such a way that it identifies with the individual’s self-concept. In other words, passionate individuals like their job and find it personally important to them. In addition, the concept of job passion can be further divided into two distinct types that give the construct a double-edged character with implications for work well-being: harmonious and obsessive passion [52]. On the one hand, harmonious passion refers to a voluntary and autonomous internalization of the job due to liking the job itself. On the other hand, obsessive passion refers to an oppressive internalization of the job due to certain pressures attached to it. Whereas harmonious passion drives individuals to invest time and effort in their jobs with a sense of control (because they like it and want to), the pressures intervening in obsessive passion would steal their sense of control, making them feel obligated to invest time and effort to satisfy these pressures. The relationship between job passion and employee performance has been researched very little until now [53]. We only found two studies on EWB–performance relationships involving job passion. One of these studies [53] reported a positive relationship between harmonious job passion and global work performance, supporting the HPWT, and this relationship was mediated by absorption, a dimension of cognitive engagement. However, in this study, the relationship between obsessive job passion and the same global performance indicator was not significant. The expected hypothesized paths with the mediating role of cognitive engagement (broken down into absorption and attention) were not supported and failed to support the mediation hypothesis. Additionally, Pradhan and colleagues [54] found that job passion is positively correlated with global performance and positively moderates the relationship between purpose and performance. Therefore, they concluded that, along with purpose, workers need to be fueled with passion on a continuous basis to drive performance.

EWB as Work Engagement. Work engagement has been conceptualized in the literature in two main ways. One refers to present states of vigor, dedication, and absorption at work [33], and the other refers to the investment in the job of the preferred-self with a clear future orientation [34]. Here we focus on the present-oriented measure, and later we will describe the future-oriented one. Engagement has been defined and operationalized (mostly by the UWES scales) as a positive, fulfilling, work-related present state of mind characterized by the presence of vigor, dedication, and absorption [33,55]. This construct has gained relevance in work and organizational literature [56,57,58,59], and it has become the main operationalization of eudaimonic well-being due to its relationship with desirable outcomes, including performance [60]. Although it has sometimes been described as “positive effect associated with the job” [61] that includes components of job satisfaction and, as such, could somehow be considered an indicator of hedonic well-being, work engagement, as operationalized by Schaufeli and Bakker, mainly combines feelings of persistence, vigor, energy, dedication, absorption, enthusiasm, alertness, and pride [18]. These constructs are more related to the sense of full functioning embraced by eudaimonia. In its main operationalization, González-Romá, Shaufeli, and Bakker [62] proposed inverse conceptual parallelism between work engagement and burnout, a well-known negative indicator of well-being that is defined as a reaction to chronic occupational stress characterized by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and lack of professional efficacy. In contrast, work engagement implies high levels of energy, resilience, and willingness to invest effort in one’s work (vigor), a sense of significance, inspiration, and determination challenge (dedication to overcoming challenges), and fully concentrating on and being engrossed in one’s work (absorption).

Work engagement operationalized by the UWES and similar questionnaires is by far the most widely used indicator of EWB, with 145 relationships studied (77.13%). Of these relationships, two were negative, 12 were non-significant, and 131 were significant and positive. More specifically, we found 38 positive, 1 negative, and 5 non-significant relationships between work engagement and task performance, 48 positive, 1 negative, and 3 non-significant relationships with contextual performance, 20 positive relationships and 2 non-significant relationships with creative performance, 7 negative relationships (coherent with the HPWT, the more engaged, the less counterproductive) with counterproductive behavior, and 18 positive and 2 non-significant relationships with global performance.

3.1.2. EWB Future-Oriented Conceptualizations

EWB as Meaning of Work. Meaning of work (MoW) refers to the amount of significance work has for an individual [63]. It can be briefly described as the extent to which one perceives his or her work as important and leading to self-actualization [64], thus, it is a future-oriented eudaimonic construct. In the present review, we only found five well-being–performance relationships that consider the MoW as an indicator of EWB. All of them were positive relationships: three with task performance, one with contextual performance, and one with global performance. We did not find any studies on the links between MoW and creative or counterproductive indicators of performance. Our review also found one study [50] that analyzed two relationships between activity worthwhileness, a similar construct to MoW, and employee performance. One of them showed a positive link between activity worthwhileness and contextual performance for workers whose physical office spaces (e.g., open-plan offices, individual offices) fit their job patterns (i.e., their task complexity and required interaction with others), whereas no significant relationships were found in workers with no fit. The other relationship analyzed in this study (i.e., the association between activity worthwhileness and task performance) was not significant.

EWB as Job Involvement. Job involvement can be defined as a cognitive or belief state of psychological identification with one’s job that depends on its potential to satisfy the individual’s needs [65]. The relationship between job involvement and performance is based on the assumption that this state of psychological identification with the job precedes and triggers processes that influence performance, as well as motivation, effort, turnover, or absenteeism [66]. We found nine relationships with job involvement as an indicator of well-being, four of them showing evidence of positive links: three with contextual performance and one with creative performance. We also found four non-significant relationships: positive with task, contextual, and creative performance, and negative with task performance.

EWB as Flourishing or Psychological Well-Being. Psychological well-being (PWB) and flourishing are perhaps the most eudaimonic well-being constructs because they gather a broad range of positive psychological-functioning features that they share to a great extent. Moreover, the first conceptualization and operationalization of PWB, offered by Ryff [9], encompassed various dimensions, such as self-acceptance, positive relations, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth, which define what happiness means in a broad eudaimonic sense, not only at work but in different life domains. Similarly, flourishing has been described as the experience of life going well, reflecting a broad conceptualization of clearly future-oriented psychological well-being characterized by individuals who perceive that their life is going well as they function effectively and feel good [67]. Like PSW, flourishing includes positive-functioning aspects such as positive relationships, feelings of competence, and having meaning and purpose in life [68]. Despite its relative novelty, different operationalizations of flourishing have been developed [69]. These operationalizations depict a concept that includes both hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of well-being [68]. Nevertheless, they represent a flourishing construct that refers predominantly to positive-functioning features (i.e., cultivating strengths, experiencing flow) with factors such as engagement, positive relationships, meaning, and accomplishment [23], which correspond to the eudaimonic view of well-being, regardless of the presence of positive emotions more related to the hedonic view. Interestingly, Huppert and So [68] utilized a symptom-combination methodology similar to the one used to identify mental health disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manuals of Mental Disorders [70] to offer an operational definition of flourishing. Based on the diagnostic criteria for depression and anxiety, these authors identified their opposite (positive) symptoms and developed and validated an operational definition of flourishing, which would be viewed as diagnostic criteria for well-being and includes the features of competence, emotional stability, engagement, meaning, optimism, positive emotion, positive relationships, resilience, self-esteem, and vitality. Perhaps due to their broader scope, not specifically focused on work, PWB and flourishing have been studied less than other more clearly work-oriented constructs such as work engagement. Our review only found two studies that used flourishing as an indicator of well-being. One of them [71] found a positive and significant relationship with creative performance and a null relationship with contextual performance. The other study [72] found a positive relationship between flourishing and task performance. Moreover, our review also found two studies that analyzed the relationship between PWB and performance, revealing two positive PWB-global performance relationships. Curiously, these studies, [73] and [74], used Diener and colleagues’ [75] flourishing scale as a measure of PWB, which is a clear example of the overlap between the two constructs.

EWB as Calling. Calling has been defined as a meaningful job that involves helping others or contributing to a greater good [76]. People who have a calling experience more meaningfulness and satisfaction at work, and they focus on the noble goals of their work rather than on financial gains [77,78]. Moreover, having a sense of calling enables people to engage in and commit to their work and careers, which fit their personal goals and values, helping them to perform better and overcome challenges they might face [78,79,80,81]. We found one study that analyzed the relationship between calling and global work performance and showed a positive and significant link.

EWB as Purpose. Purpose has been identified as one of the core components of eudaimonic well-being [82]. It refers to a sense of directedness in life, a feeling of significance of the present and past, and having aims and objectives in life [9]. Purpose in life answers fundamental questions such as “What makes my life worth living?” [82]. In a similar vein, Leider [83] described purpose as “the aim around which we structure our lives, a source of direction and energy” and “an active expression of the deepest dimension within us [...] a profound sense of who we are and why we are here” that “gets you out of bed in the morning” (p. 7). When we discover purposeful moments, we are able to display high levels of energy to perform our role in the best way possible [83]. We found one positive relationship between purpose and global performance in our review, showing that when people are able to find purpose in their work, they also show higher levels of performance [54].

EWB as Engagement. As mentioned above, engagement has been conceptualized from two different perspectives. The future perspective approach proposed by Kahn [34] is a state in which employees bring their personal selves into their work role, investing personal energy and experiencing an emotional connection with it. Kahn’s view of engagement is the most comprehensive because it involves the important component of personal agency. Being engaged is a matter of personal choice, where individuals decide to what extent they bring their true selves into their work, which depends on the extent to which they derive meaning from their work (psychological meaningfulness), are able to express their true selves without fearing negative consequences to their self-image or career status (psychological safety), and have the necessary resources to do so (psychological availability). In the studies reviewed in this paper, this conceptualization and operationalization of engagement have received some attention. We found three positive relationships with task performance, four positive relationships with contextual performance, one positive relationship with creative performance, and two negative (supporting the HPWT) relationships with counterproductive performance.

3.2. Moderating and Mediating Variables Affecting EWB–Performance Links

Two interesting aspects, often shown in studies, that test the HPWT are the consideration of mediating variables, in order to better understand the paths or mechanisms of the relationship and the boundary conditions, or moderating variables, in order to identify under what conditions these relationships are significant or stronger. Our review yielded 47 EWB–performance relationships that were studied considering interaction effects and/or mediated by other variables.

Personality characteristics have received important attention as moderators. Chu and Lee [84] reported moderating effects of conscientiousness and emotional stability in the relationship between flow experiences and global performance, where the flow–performance relationship was stronger for workers who were higher in these traits. Additionally, Chen, Richard, Boncoer, and Ford [85] showed that these two moderators also influenced the indirect effect of work engagement on counterproductive behaviors through emotional exhaustion; thus, they concluded that engaged individuals who were conscientious and emotionally stable experienced less performance deviance, due to a decrease in their emotional exhaustion. In this line, Bakker, Demerouti, and Brummelhuis [86] also reported relationships between work engagement and task and contextual performance moderated by employees’ conscientiousness, such that the engagement–performance relationships were significant only for highly conscientious workers.

Alessandri and colleagues [87] reported a moderating effect of self-efficacy beliefs in the relationship between work engagement and global performance, where the effect of work engagement on performance was significant only for workers with high and medium levels of self-efficacy, but not for workers with low self-efficacy. Interestingly, contextual factors have also been considered as moderators. For instance, Harris, Kacmar, and Zivnuska [88] found that the meaning of work affected task and global performance only in the interaction with abusive supervision; employees with high-meaning tasks and global performance resented their abusive supervisor more strongly than their low-meaning coworkers. Another contextual factor that moderates the relationship between engagement and different performance indicators is organizational support. Thus, perceived organizational support has been found to moderate the relationship between engagement and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB, both individual and organizational) [89] and between engagement and task performance [90]. In this line, Gupta, Shaheen, and Reddy [89] argued that engaged employees’ extra-role behavior is based on the social exchange theory, which states that people tend to reciprocate the benefits they receive [91]. Moreover, the adequacy of the office type for the type of tasks office workers usually perform at work was found to moderate the effect of activity worthwhileness and extra-role performance [50]. Finally, Stollberger and Debus [92] highlighted that the relationship between daily flow and daily creative performance is stronger in people with high flow variability.

In studies that have included mediating variables to better understand the relationships between EWB and different types of performance, it is relevant to note that, in many cases, the mediating variable(s) is another facet of well-being. Gorgievsky, Moriano, and Bakker [93] found that the relationship between work engagement and creative performance was mediated by both positive and negative effect. Ho, Wong, and Lee [53] found that cognitive absorption (a dimension of cognitive engagement) had a mediating role in the relationship between job passion and global performance. Finally, there are also well-being dimensions that have been found to mediate the EWB–performance relationship. For instance, Medlin and Green’s [94] results suggest a mediating role of workplace optimism in the relationship between work engagement and global performance, although they did not test the significance of the indirect effect.

In some cases, the mediating variables between EWB and performance are not well-being constructs. Studies have shown, for example, that the relationship between engagement and performance is mediated by the use of flexible human resource management practices [95], personal initiative [59], and innovative behavior [58]. This latter construct also mediates the relationship between engagement and task performance [96]. Additionally, Van Wingerden and Van der Stoep [97] showed that the meaningful work–task performance relationship is best predicted by multiple pathways via employees’ use of strengths and work engagement. Finally, one study found that an indicator of performance (individual-oriented OCB) mediates the relationships between work engagement and two other indicators of task performance (i.e., two dimensions of quality performance) [98].

In sum, together these findings point to a positive trend in the literature supporting the HPWT when eudaimonic indicators of well-being are considered. However, empirical evidence mainly shows support for present-oriented constructs, especially work engagement as present states of vigor, engagement, and absorption, whereas evidence for the rest of the constructs is scarce. Moreover, despite the emerging diversification of the indicators of EWB, with more future-oriented constructs coming onto the scene in recent years, their quantitative role is still very limited in comparison with present-oriented EWB or, more specifically, work engagement. These results indicate that the research on the eudaimonic facet of the HPWT has mainly focused on the part of EWB that refers to the immersion, deployment of capacities, and enjoyment currently present at work. However, the part referring to the way individuals pursue self-development, meaning, and purpose, striving to attain higher levels of themselves that are aligned with their identity and future perspectives, has been considered much less and deserves more attention.

3.3. Evidence on the Bidirectionality of the EWB–Performance Relationships

A final important aspect of the relationship between EWB and performance is its directionality. The happy productive worker thesis has defended a directionality that goes from well-being to performance. That is, ceteris paribus, a happy employee will be a productive one. Nonetheless, some authors have questioned this directionality [5], and so we have incorporated this question into our review.

The review of the empirical evidence shows that the majority of the relationships included in this review (97.34%) examine the well-being–performance direction, and only four studies have analyzed a total of five relationships in the well-being to performance direction. Choi, Tran, and Park’s study [99] reported two significant relationships between organizational commitment (the desire and willingness to stay with the organization) and engagement, and between creative performance and work engagement. The authors based their argument on the premise that creative employees tolerate anxiety better and have more lateral thinking, and they receive compliments and respect for their work, which helps them to be more focused on their work. Generally, they are more likely to have a positive mood and feel enthusiastic and motivated in their work, thus becoming more engaged. Moreover, the authors explain that employees who are highly committed to the organization are more likely to show high engagement because they value their work and develop positive attitudes towards their organization and work activities. Saradha and Harold [100] suggest that OCB is a driver of engagement. The theoretical link seems to be based on the capacity of OCB to foster an adequate social environment within the organization, although it is not completely clear. In a similar vein, two other studies [101,102] found positive relationships between different indicators of contextual performance (workplace spirituality and affective commitment) and work engagement, based on SET and the principle of reciprocity. The general premise is that engagement is a way for employees to reciprocate the resourceful and socially adequate work context facilitated by contextual behaviors.

It is worth noting that the conceptualization of performance was not task performance, as in the majority of the relationships, but rather OCB, commitment, and creative performance, all three with engagement. There could be two explanations for this. First, it is possible that the HPWT has had such an influence that researchers do not hypothesize relationships in the opposite direction (that is, from well-being to performance), even though some theoretical approaches suggest this possible bi-directionality [5]. Some recently published articles incorporate this research question [11]. However, this research is still scarce and should be further studied with eudaimonic well-being or other well-being indicators, such as health-related operationalizations.

Second, it is possible that this bidirectionality does not work with task performance when studying eudaimonic well-being. Task performance is a compliance variable stating that you do what you have to do and nothing else. Thus, the employee is not expected to perform beyond what is required, whereas eudaimonic well-being is more related to the purpose of growing professionally and looking for more purpose in life. Indeed, we have found relationships with OCB, commitment, and creative performance, which are variables that go beyond what is expected from employees to help colleagues, pursue social relationships, feel motivated, and have a positive mood at work.

3.4. Theoretical Foundations behind the EWB–Performance Studies

One intriguing question in this systematic review has to do with the underlying theoretical approaches that guided the studies on EWB–performance relationships. In this section, we review the main theoretical views considered to hypothesize and/or explain most of the relationships studied in our review. We also consider theories and models that explain the relationships between specific indicators of EWB and specific indicators of performance. In order to organize the array of information on this topic, we will follow the time focus of the EWB constructs (i.e., present-oriented vs. future-oriented focus) introduced previously.

3.4.1. Theoretical Rationale for the Relationships between Present-Focused EWB and Performance

Over three-quarters of the EWB–performance relationships reviewed in this paper refer to work engagement as vigor, dedication, and absorption, depicting a motivational and energy-driving construct focused on present states. Consequently, most of the theoretical rationales found in this review have been used to explain the relationships between this present-oriented view of work engagement and different indicators of employee performance.

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model [103] states that engagement is promoted by the availability of external and personal resources at work. When analyzing the relationships between engagement and performance, this theory has been used, mostly to justify the mediating role of engagement in the relationship between job resources and performance. Mastenbroek and colleagues [104], Lorente and colleagues [105], and Borst [106] used the JD-R model to explain the relationships between job/personal resources-engagement-task/contextual performance. Literature supports the idea that engaged employees are more energetic and emotionally connected to their tasks (leading to higher task performance) [107,108], and they also go beyond the formal requirements of their job description to engage in contextual performance [107] or innovative behaviors [109]. Job resources have a motivational power that leads to work engagement and, consequently, to performance. Chung and Angeline [110] also refer to these arguments, and Li and Qi [111] use the JD-R and conservation of resources (COR) theories to hypothesize the mediating role of engagement in the relationship between supervisors’ knowledge-sharing and task performance. Other authors combine the JD-R rationale with other theories to describe the relationship between engagement and work performance. Sulea and colleagues [112] combine the JD-R model with Social Exchange Theory (SET) and Broaden-and-Build Theory (BBT) to explain the mediating role of work engagement in the relationship between job resources (organizational support) and OCB, and between job stressors (interpersonal conflict) and counterproductive work behavior (CWB). According to the authors, job resources facilitate both the reciprocation and positive emotions that are characteristic of engaged employees, which in turn facilitate OCB and decrease CWB. In this line, Ariani [113] emphasizes that social exchange and the emotional explanations can be related because both reciprocity and positive emotions are the result of favorable treatment from the organization [114].

The Social Exchange Theory. (SET [91]) is one of the most influential theories in psychology and organizational behavior [115]. According to the SET, social exchange involves interactions that create obligations between the parties [116]. They have the potential to produce higher or lower quality relationships depending on the extent to which they fit the given norms and rules of exchange. Reciprocity is a nearly universal social norm [117], and it operates as the main exchange rule in the SET. It basically means that people expect to receive resources or actions of similar value to the ones they give, or, vice versa, people tend to respond with resources or actions of similar value to the ones they receive. This simple rationale underlies many aspects of social interaction and fits the HPWT, including its eudaimonic facet. Our review reveals that the SET and the principle of reciprocity have been used as theoretical arguments for EWB–performance relationships. On the one hand, Gichohi [118] relied on the SET to explain the mediating role of engagement, paying the organization back with engaged behavior in exchange for the empowerment and training received. On the other hand, Ariani [113] argued that the SET and the norm of reciprocity underlie the relationships between engagement and contextual (OCB) and counterproductive work behavior analyzed in their study. Engaged employees enjoy a motivating work environment that provides them with work-related positive emotions, which they tend to reciprocate by engaging in constructive and responsible behaviors at work, such as OCBs. Conversely, when employees are disengaged, they might feel that their work context is unpleasant and engage in counterproductive behaviors as a means of retaliating against their employers for not providing them with a motivating job. Moreover, they argue that employees who engage in OCB are unlikely to perform counterproductive behaviors. Finally, recent studies have linked engagement with different indicators of performance, such as task performance (e.g., [119,120]) or contextual performance (e.g., [89,101]), based on the assumptions of the SET theory.

The Self-Regulation Theory. (SRT, [121]) posits that individuals set goals, compare their progress to them, and make behavioral or cognitive modifications in order to close the gaps (discrepancies) between the goal and the current state. In the study by Lin and colleagues [122], SRT serves as the theoretical argumentation for the work engagement-task performance link. The positive, fulfilling, and energizing state of mind experienced by engaged individuals promotes a vigilant, attentive, and focused state that enhances selective attention, shields motivation, fosters the accessibility of information relevant for goal attainment, and improves individual competencies [121].

The Broaden and Build Theory. (BBT, [123]). The unfolding paths that play a role in the relationships between engagement and performance have also received attention. In this context, the BBT theory assigns a prominent role to positive emotions. This theory posits that positive emotions broaden people’s thought-action repertoires and build personal resources. Bakker, Demerouti, and Brummelhius [86] frame the effects of engagement on contextual and task performance in the BBT and the positivity, behavioral openness, and helping tendencies that are facilitated by positive emotions. Other studies (e.g., [109,110,124,125,126] also refer to the BBT or to positive emotions, pointing out that engaged employees, because they are more positive, enthusiastic, energetic, and healthy, increase their task, contextual, and creative performance. Bakker and Xanthopolou [127] also use the BBT, considering that it helps workers to more easily establish connections between divergent stimuli [128], leading to better integration of resources and higher creativity in problem-solving. Based on the BBT and on the componential theory of creativity (CTC, described in the paragraphs below), the authors propose that engagement is a motivational experience that expands the self through learning and goal fulfillment, resulting in higher creativity.

A similar mediating role is assigned to harmonious passion (the dual model of passion distinguishes it from obsessive passion), which, when present in engaged workers, provides them with vitality and positive emotions that, according to the BBT principles, would lead to broadening the scope of attention and then to engagement [93]. A similar rationale is also explicitly used by Ho, Wong, and Lee [53], who proposed cognitive engagement (absorption and attention), measured as close to UWES, as a mediator between harmonious and obsessive passion and performance. Harmoniously passionate workers are more cognitively engaged in their jobs, more focused and concentrated, and more able to overcome obstacles, and so they present higher performance. Ho and colleagues base their arguments about the cognitive engagement–performance relationships on ideas from human information processing theories (e.g., [129,130]). They argue that the greater the cognitive capacity (attention) devoted to the tasks, the better the performance, thanks to an increased capacity to come up with alternative solutions to problems and take advantage of opportunities to increase performance and self-development when they appear. They found support only for the absorption–performance relationship, suggesting that the quality, rather than the quantity, of the cognitive resources invested in work is what increases performance.

Finally, regarding other indicators of EWB, Stollberger and Debus [92] stated, in line with the broaden and build theory, that higher levels of flow are associated with more flexible, unusual, and novel cognitions and behaviors at work (due to a more extensive thought and action repertoire), making them more creative.

Componential Theory of Creativity. (CTC, [131]) has been used to theorize about the relationship between engagement and creative performance. According to this theory, human beings are capable of creative performance as long as three conditions are fulfilled: expertise, creative thinking, and intrinsic motivation. Bakker and Xanthopolou [127] argued that the motivational condition is the one that determines actual behavior, and it is connected to employee work engagement. Based on previous literature [132], they argue that engaged employees are open to new experiences and motivated to invest the necessary effort to achieve excellence. Thus, they propose that engaged employees are willing to use all their skills and expertise for the sake of creative performance, in order to be energetic, dedicated, and absorbed in their work (the three engagement dimensions) and acquire new skills to be creative. Chang, Hsu, Liou, and Tsai [133]; Gichohi [118]; and Toyama and Mauno [134] also propose the motivational nature of engagement, which favors cognitive flexibility, persistence, and a sense of challenge, to establish its causal link with creative performance (innovative behaviors). However, Gichohi’s study did not find this relationship significant.

Bae and colleagues [135] benefited from the knowledge conversion theory [136] to frame the mediating role of engagement and knowledge creation practices in the transformational leadership–creativity link. According to knowledge conversion theory, the levels of employees’ work engagement and voluntary collaboration are critical for increasing creativity. The theoretical argument mainly focuses on why transformational leadership fosters engagement and, consequently, teachers’ creativity and knowledge-creation behavior, but not on the engagement–creativity link. That is, engagement’s capacity to foster performance is assumed and taken as a theoretical argument for the hypothesis.

3.4.2. Theoretical Rationale for the Relationships between Future-Focused EWB and Performance

Although the research overwhelmingly concentrates on present-focused EWB constructs when studying their relations with performance, a number of studies have focused on future-oriented constructs such as flourishing and self-development. This section gathers the constructs found in the review that focus on the future, which is an important added value of the EWB, and the theoretical arguments used to connect them with performance.

Kahn’s View of Engagement. Some studies have used Kahn’s [34,137] view of engagement as the total investment of one’s “preferred self” in the job. This implies that engaged people invest cognitive and emotional energies that foster active and complete role performance through extra conscientious, interpersonally collaborative, innovative, and involved behaviors that allow them to connect with and express themselves through their work (including their personal values, beliefs, and connection to others). Therefore, this vision of engagement is broader and implies an integral investment of the employee in his/her job, including aspects such as personal values, beliefs, and connectedness to others. This integrity seems to be more in line with the conception of the human being as a living totality offered by the person-centered approach to (work) psychology. Rich and colleagues [138] found a positive relationship between Kahn’s type of engagement and task performance and OCB. These authors argue that to the extent that engaged employees dedicate themselves more fully while at work, they are more willing to engage in acts that constitute OCB. Moreover, to the extent that engagement is reflected by meaningfulness and connectedness to one’s work [137], it may foster a mental frame in which one’s role is perceived as including a wider array of behaviors that could ultimately benefit the organization. Indeed, Kahn [34,137] argued that the physical, cognitive, and emotional energies of engagement foster active and complete role performance through behavior that is conscientious, interpersonally collaborative, innovative, and involved. Alfes and colleagues [139] also consider Kahn’s conceptualization of engagement as the basis for their hypothesized relationship between engagement and task and creative performance (innovative behavior). Engaged employees have cognitive, social, and emotional connections with their work that promote creative performance because they dedicate themselves to their role, establish meaningful connections with others, and experience positive cognitions and emotions when performing their tasks. Wickramasinghe and Perera [98] also base the relationships between engagement and contextual (individual-oriented OCB’s) and task performance (quality performance) on the high investment of energy and one’s self in the job. Moreover, individual-oriented OCBs mediate the relationship between engagement and quality performance. However, the same study did not find significant relationships between work engagement and organization-oriented OCBs. The authors attribute this difference in the preference for performing individual- vs. organization-oriented OCBs to time constraints that keep workers from engaging in both, with co-workers’ need for help being more immediately salient for employees than the company’s objectives.

It is interesting to note that a number of studies that operationalize engagement using the UWES scales (vigor, dedication, and absorption) also interpret their results using Kahn’s views of engagement. For instance, Chang and colleagues [133] find that the energy investment characteristic of engagement [34] is crucial to creative performance (innovative activities). Moreover, Chen [107] refers to the concept of a person’s preferred self and the notion of individuals investing themselves more fully at work to explain the positive relationship between engagement and task and contextual behaviors.

Job Involvement Theory. Nwibere’s [140] study also found links between job involvement and contextual performance (OCB). The rationale underlying these relationships is mainly based on Kanungo’s theory of job involvement, which overlaps somewhat with Khan’s vision of engagement in the sense of identification and expression of one’s self at work. The author highlights that job involvement represents psychological identification with one’s job [65], and it involves the internalization of core values about the goodness of work in the individual’s worth [141]. Highly involved employees consider their work to be central, and their self-concept and self-esteem are aligned with the way they perform their jobs. As Kanugo [65] states, jobs “define one’s self-concept in a major way”. These characteristics of involved employees would make them invest themselves in their jobs and engage in OCBs, which are a matter of personal choice and depend on the individual’s motivation, for the sake of their organization. Here a clear eudaimonic perspective explains the job involvement–performance relationships, giving a lead role to identification with their self-concept and self-esteem, which is related to the high meaning and purpose that involved workers give to their work.

The Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory. [142] has also been used to explain the EWB–performance relationships with indicators other than work engagement. For instance, Harris, Kacmar, and Zivnuska [88] attribute the substantially higher task performance self-ratings of high-meaning workers over low-meaning workers to the large number of personal resources (physical and emotional) the former invest in their meaningful jobs. According to the authors, the self-ratings might reflect this high investment in their work, the high value of the resources they have invested, and the high purpose experienced in their work. This study found an interaction effect of meaning of work in the relationships between abusive supervision and job performance, such that abusive supervision was more damaging to performance for the high-meaning employees. Based on the COR theory, they argued that these individuals spend a large amount of energy and effort dealing with their abusive supervisors, ultimately draining their resources and negatively affecting their job performance to a greater extent than their low-meaning counterparts. Eldor and Harpaz [143] also use a resource-investment approach (COR theory) to explain that an enriching learning climate where employees can draw on a number of resources will promote extra-role performance (including creativity). This climate stimulates the investment of the employees’ self, in terms of job involvement and engagement, which contributes to better performance. In turn, this performance creates new opportunities for employees to take advantage of additional resources in an upward gain spiral dynamic between employees’ resource investment and subsequent gains through improved extra-role performance. More specifically focused on engagement, Alessandri, Consiglio, Luthans, and Borgogni [56], in line with the COR theory, argued that work engagement increased individuals’ ability to invest effort in their work activities, thus increasing their performance.

Finally, it is worth noting that two papers have studied the relationship between flourishing and performance ([71,72]). Demerouti and colleagues base the hypothesized relationships between flourishing and contextual and creative performance on the broaden and build theory because they assume that flourishing presents positive emotions that will stimulate extra-role behaviors. In fact, the results showed positive significant relationships with creativity, but not with contextual performance, and the authors interpret this following the positive emotions–creative performance link. However, the construct of flourishing involves other components that require further consideration to better understand its relationship with different facets of performance. Future studies should consider not only the component of feeling good but also the one related to effectively functioning with a future orientation. Other specific future-oriented EWB constructs, such as calling and purpose, have been studied through the lens of specific theories. For example, Park and colleagues [144] analyzed the relationship between calling and global performance based on the work as calling theory, which states that calling is linked to positive work outcomes, including job performance, through the mediating role of commitment to the career. Another study [54] analyzed the relationship between purpose and global performance. The authors propose a remarkably eudaimonic explanation for their hypothesized role of purpose (and also passion) as an antecedent of global performance by mentioning the identity perspective in role investment theory, referring to the investment of cognitive time and attention that is associated with finding one’s task to be pleasurable and important [145] and a potential source of self-actualization [119].

In sum, to explain the relationship between the present-focused EWB constructs and performance, a number of theories have been used. The JD-Resources model points out that engagement is enhanced by the available resources, whereas the SET theory pays attention to the role of EWB in improving performance through reciprocity. SR theory, in turn, establishes that engagement stimulates goal setting and achievement, thus linking the EWB to performance. Moreover, several studies have paid attention to the role of positive emotions in the relationships between EWB and performance. The broaden and build theory has been especially fruitful in this endeavor, and the theory of dual passion has also been used for this purpose, suggesting the importance of the combination of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in promoting different types of performance. Finally, the componential theory of creativity and knowledge-conversion theory have provided the rationale for linking engagement to creative performance.

In the case of future-oriented EWB, in spite of having received much less attention, the theories emphasize employees’ investment in their jobs as a strategy to develop their own identity and purpose in life. Thus, both Kahn’s theory of engagement (investment of the person’s preferred self in his or her work) and Kanugo’s theory of job involvement emphasize that EWB, as an important experience for identity development, promotes work performance. The concept of investment is also used in the COR theory to explain why high EWB, in terms of meaningful work, stimulates higher performance. Finally, other future-oriented EWB constructs have hardly been studied, and not much theoretical elaboration is provided, apart from their influence on performance through the BBT. Future research is needed to better understand the links between future-oriented EWB and different types of performance and its continuity in sustainable careers [146].

All the theories identified in our review focus on justifying the happy-productive link. The only exception is the self-regulation theory, which involves an ongoing process of comparing progress to the goals the individual sets for him/herself. Thus, when performance goals are achieved, there would be a resulting experience of internal satisfaction and a willingness to dedicate even more energy and dedication to continuing to achieve further objectives, implying a cycle of happy-productive-happy links. There is a need to develop a more comprehensive theoretical model to explain how, why, and when these productive-happy relationships occur.

4. Discussion and Future Research Agenda

The aim of this study was to provide a systematic review of empirical studies focusing on the relationship between EWB and performance by identifying empirical evidence, including reverse relationships, and theoretical grounds for considering EWB instead of hedonic, which is usually considered in the HPWT model. One key point was to identify how EWB has been conceptualized and operationalized in the empirical research designed to relate it to performance. We found a variety of facets pointing to several interesting trends. To begin with, most of the studies focused on engagement, which makes sense because it is a construct closely related to performance, especially to types of performance that go beyond in-role tasks [61]. In the reviewed studies, engagement has always been conceptualized as a state, and no attention has been paid to its trait or behavioral conceptualizations. In this latter case, the main behavioral components refer to performance (OCB, proactive performance, etc.), and they are considered indicators of productivity in many studies. A close look at its operationalization as a state shows two main approaches. Most studies operationalize engagement as a present psychological state of vigor, dedication, and absorption, operationalized by the UWES questionnaire [33,55]. At the same time, some attention has been paid to Kahn [34], with the focus on the employees’ sense of self-identity in their work, investing in their preferred role to enhance self-fulfillment and development. Thus, in this case, the psychological state has a purpose and is rather future-oriented.

Empirical evidence included in this review provides support for the HPWT when examining eudaimonic facets of well-being. However, there are some specific aspects to consider: this support is very solid and robust when EWB is operationalized as present-oriented engagement. The support is also clear when considering engagement as conceptualized by Kahn [34], although the number of studies is rather limited. Other EWB constructs with a present focus, such as flow or passion, have also received less attention. In sum, support for the HPWT with EWB is well established for engagement in its different facets (especially with contextual performance). An important reason for the study of engagement based on the EWB–performance relationships is the consideration of engagement as a proxy for performance behavior [61]. However, future research should develop a proper measurement of the engagement psychological state as conceptualized by Kahn, clarify its specific contribution to performance and other key behaviors and outcomes, and further analyze the relationship between other present-oriented EWB indicators such as flow or job passion.

With regard to other EWB constructs, especially those with a future orientation, the evidence is quite limited and non-conclusive. When employees are more oriented toward self-fulfillment, realization, and future-oriented purposes, they may be less focused on performance achievement. It seems that as EWB operationalizations are more distal to the present performance, the relationship may be weaker than with the more proximal operationalization of engagement. Moreover, as Bartlet and colleagues [147] point out, a comprehensive conceptualization of EWB in the workplace is missing, and in some cases, scholars had to use proxy constructs from other life spheres. These authors point out that employees’ engagement does not properly cover the nature of eudaimonic workplace well-being. Considering these ideas, future research is needed to develop the construct and measurement of the facets of eudaimonic workplace well-being, especially those that include people’s sense of self-identity with their work. Future research should also need to clarify the ambivalent relationship between these future-oriented EWB constructs and different types of performance, especially contextual, creative, and innovative performance, as well as other relevant outcomes, such as career success.

When it comes to the directionality of the EWB–performance relationships, the studies reviewed hardly paid attention to the performance–EWB relationship or their reciprocal influence. The HPWT assumes unidirectionality of causality from well-being to performance when studying this relationship, and in our review, only two studies analyzed the opposite direction for this relationship. The theory supporting the hypotheses was self-regulation because it analyzes not just goals and the behaviors to achieve them, but also a dynamic feedback loop that is an essential part of the dynamic cycle [148]. In fact, some authors have pointed out the need to test reciprocal relationships between EWB and performance [11,149]. A reciprocal relationship in a positive spiral is important to guarantee sustainable well-being and performance at work. Therefore, it is important to further explore under what conditions and paths EWB leads to better performance, and how achieving good performance increases EWB in a sustainable spiral. With this in mind, the present systematic review highlights an important gap that future studies should cover by analyzing the dynamism and reciprocity in the relationship between these two important constructs.