Communicating Sustainable Responsible Investments as Financial Advisors: Engaging Private Investors with Strategic Communication

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Role of Financial Advisors for Sustainable Responsible Investments

3. Challenges of Sustainable Responsible Investments

4. Challenges of Financial Advisors

5. Challenges of Private Investors

6. Theoretical Models for Moral and Ethical Investment Behavior

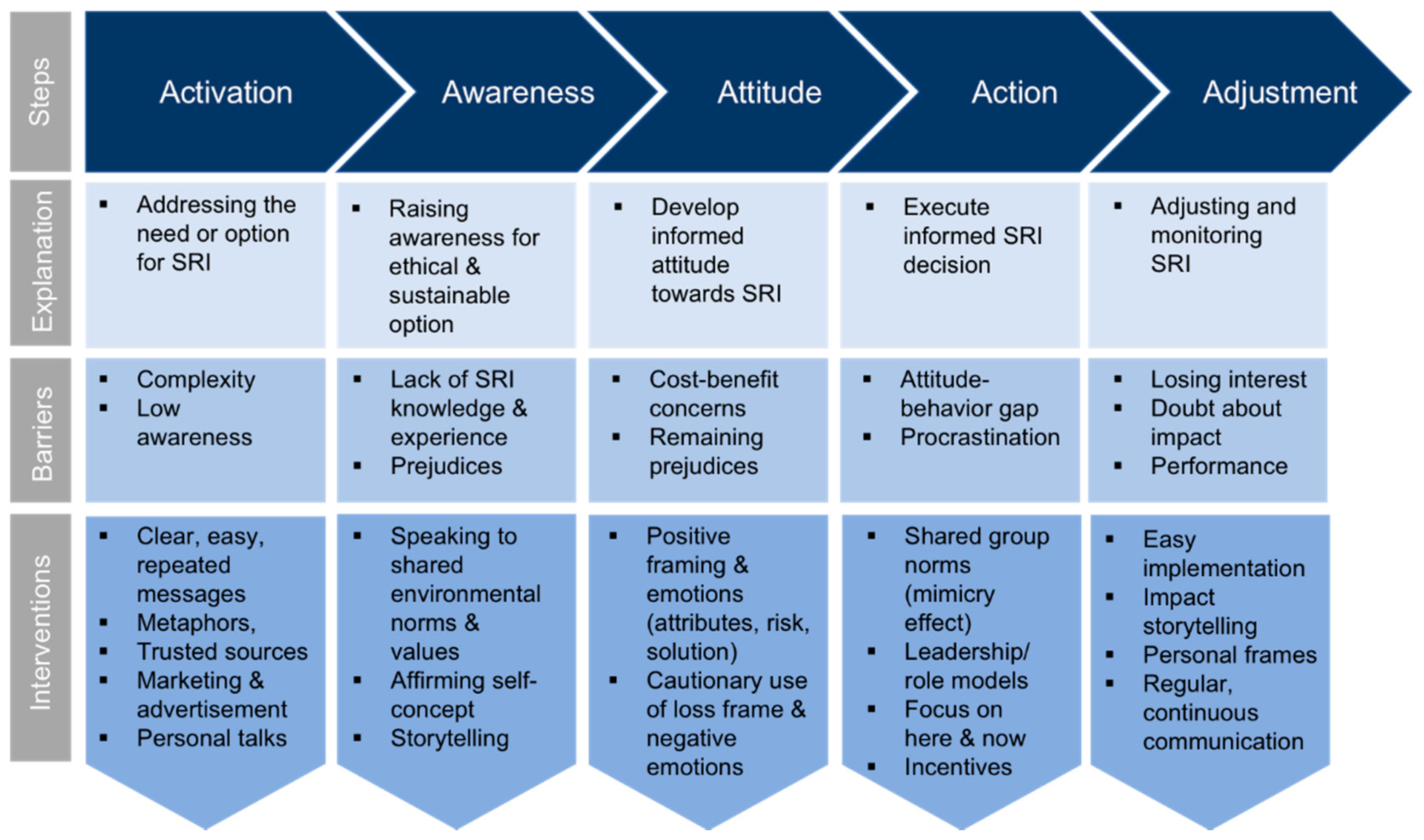

7. Strategic Communication Interventions in Financial Advisory Talks

7.1. Activation

7.2. Awareness

7.3. Attitude

7.4. Action

7.5. Adjustment

8. Summary and Practical Implications

9. Limitations and Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Economist. The Economist Explains: What Is Sustainable Finance? The Economist: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.ecomist.com/the-economist-explains/2018/04/17/what-is-sustainable-finance (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Webb, M.S. The Many Confusing Shades of Green for Investors; Financial Times: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/49c4634d-a90b-4113-85f5-311077e56812 (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Bioy, H. ESG Funds Assets Hit £800 Billion. Morning Star, 2020. Available online: https://www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/news/206906/esg-funds-assets-hit-£800-billion.aspx (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Bioy, H. Global Sustainable Fund Flows: Q3 2020 in Review. Morningstar Manager Research, 2020. Available online: https://www.morningstar.com/content/dam/marketing/shared/pdfs/Research/Global_Sustainable_Fund_Flows_Q3_2020.pdf?utm_source=eloqua&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=&utm_content=25660 (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Libby, S.; Carré, O. 2022: The Growth Opportunity of the Century. PWC Report, 2020. Available online: https://www.pwc.lu/en/sustainable-finance/docs/pwc-esg-report-the-growth-opportunity-of-the-century.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Caldecott, B. Introduction to special issue: Stranded assets and the environment. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2017, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S. Climate Change Could Make Premiums Unaffordable: QBE Insurance. Reuters, 2020. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-qbe-ins-grp/climate-change-could-make-premiums-unaffordable-qbe-insurance-idUSKBN20B0DA (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Hepburn, C.; O’Callaghan, B.; Stern, N.; Stiglitz, J.; Zenghelis, D. Will COVID-19 Fiscal Recovery Packages Accelerate or Retard Progress on Climate Change? Smith School Working Paper. Available online: https://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/publications/wpapers/workingpaper20-02.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- PRI. Principles for Responsible Investment. 2021. Available online: https://www.unpri.org (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- UNSDG. Unlocking SDG Financing: Findings from Early Adopters. United Nations Sustainable Development Group, 2018. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/Unlocking-SDG-Financing-Good-Practices-Early-Adopters.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Heinemann, K.; Zwergel, B.; Gold, S.; Seuring, S.; Klein, C. Exploring the Supply-Demand-Discrepancy of Sustainable Financial Products in Germany from a Financial Advisor’s Point of View. Sustainability 2018, 10, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paetzold, F.; Busch, T. Unleashing the powerful few: Sustainable investing behavior of wealthy private investors. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soezer, A. Boosting Private Investments in the SDGs. UNDP Blog, 2019. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2019/boosting-private-investment-in-the-sdgs.html (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Singh, N. The 2019 Millennial Wealth Report at a Glance. Wealth Engine, 2019. Available online: https://www.wealthengine.com/millennial-wealth/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Cheah, E.-T.; Jamali, D.; Johnson, J.E.; Sung, M.-C. Drivers of Corporate Social Responsibility Attitudes: The Demography of Socially Responsible Investors. Br. J. Manag. 2011, 22, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UBS. UBS Investor Watch. Setting a New Course. 2020. Available online: https://www.ubs.com/de/en/wealth-management/our-approach/investor-watch/2020/setting-a-new-course.html (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- UBS. UBS Investor Watch. Return on Values. 2018. Available online: https://www.ubs.com/content/dam/ubs/microsites/ubs-investor-watch/IW-09-2018/return-on-value-global-report-final.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Sheehan, K.L. Atkinson from the guest editors: Special issue on green advertising: Revisiting green advertising and the reluctant consumer. J. Advert. 2012, 41, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, U. Ignorant advice—Customer advisory service for ethical investment funds. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2006, 15, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paetzold, F.; Busch, T.; Chesney, M. More than money: Exploring the role of investment advisors for sustainable investing. Ann. Soc. Responsib. 2015, 1, 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linciano, N.; Soccorso, P.; Capobianco, J.; Caratelli, M. Financial Advisor—Investor relationship. Mirroring Survey on Sustainability and Investments. CONSOB. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3752806 (accessed on March 12, 2021).

- Lawther, R. What Will 2021 Hold for the Financial Advice Sector? International Adviser, 2020. Available online: https://international-adviser.com/what-will-2021-hold-for-the-financial-advice-sector/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Medlock, R. Lifting the Lid on the EU’s Sustainable Finance Action Plan. FT Advisor, 2020. Available online: https://www.ftadviser.com/Partner-Contents17/2020/10/09/Royal-London-Lifting-the-lid-on-the-EU-s-Sustainable-Finance-Action-Plan (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Murray, S. ESG Investing Cries out for Trained Finance Professionals. Financial Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/d92a89ec-740c-11ea-90ce-5fb6c07a27f2 (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Pilaj, H. The Choice Architecture of Sustainable and Responsible Investment: Nudging Investors toward Ethical Decision-Making. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 140, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Nordvall, A.-C.; Isberg, S. The information search process of socially responsible investors. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2010, 15, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiauf, T.; Schäfer, H. From integratin to impact—A new investment climate for Germany’s SRI landscape. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2014, 4, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurosif. About Us. 2021. Available online: https://www.eurosif.org/about-us/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- EU High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (EU HLEG). Financing a Sustainable European Economy. Final Report 2018 by the High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GSI Alliance. 2018 Global Sustainable Investment Review. 2019. Available online: http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/GSIR_Review2018.3.28.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Lusardi, A. Financial Literacy: Do People Know the ABCs of Finance? SSRN Electron. J. 2014, 24, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIA (Deutsches Institut für Altersvorsorge, 2020). Wie Halten es die Anleger mit der Nachhaltigkeit? Available online: https://www.dia-vorsorge.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/DIA-Studie_Wie_halten_es_die_Anleger_mit_der_Nachhaltigkeit.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Migliavacca, M. Keep your customer knowledgeable: Financial advisors as educators. Eur. J. Finance 2019, 26, 402–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings. SSRN Electron. J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupre, S.; Roa, P.F. Impact Washing Gets a Free Ride. 2020. An Analysis of the Draft EU Ecolabel Criteria for Financial Products. 2 Degrees Investing Initiative. Available online: https://2degrees-investing.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Paper-Impact-washing.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Riding, S. Greenwashing Purge Sees Sustainable Funds Lose Share in Europe. Financial Times. 2019. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/358b7993-158e-3ca5-9264-efe9b8c986ee (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Yonts, C.; Allen, J. ESG Reporting. Special Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.clsa.com/idea/esg-reporting/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Brandstetter, L.; Lehner, O.M. Opening the Market for Impact Investments: The Need for Adapted Portfolio Tools. Entrep. Res. J. 2015, 5, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormiston, J.; Charlton, K.; Donald, M.S.; Seymour, R.G. Overcoming the Challenges of Impact Investing: Insights from Leading Investors. J. Soc. Entrep. 2015, 6, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barby, C.; Gan, J. Shifting the Lens A De-Risking Toolkit for Impact Investment. 2014. Available online: https://www.bridgesfundmanagement.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Shifting-the-Lens-A-De-risking-Toolkit-for-Impact-Investment.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Cunha, F.A.F.; De Oliveira, E.M.; Orsato, R.J.; Klotzle, M.C.; Oliveira, F.L.C.; Caiado, R.G.G. Can sustainable investments outperform traditional benchmarks? Evidence from global stock markets. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 682–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.-G.; Han, Y.; Teresiene, D.; Merkyte, J.; Liu, W. Sustainable Funds’ Performance Evaluation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, T. 2020: A Bumber Year for Sustainable Investing. Fidelity International, 2020. Available online: https://www.fidelity.co.uk/markets-insights/investing-ideas/esg-investments/2020-bumper-year-sustainable-investing/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Corner, A.; Markowitz, E.; Pidgeon, N. Public engagement with climate change: The role of human values. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, D.J.; Goyen, M.; Philips, P. Why Do We Invest Ethically? J. Invest. 2005, 14, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelson, G.; Wailes, N.; Van Der Laan, S.; Frost, G. Ethical Investment Processes and Outcomes. J. Bus. Ethic 2004, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, I. Investors Pump £75 m a Week into ESG Manager. FT Adviser, 2020. Available online: https://www.ftadviser.com/investments/2020/07/07/investors-pump-75m-a-week-into-esg-fund-house/ (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Tanford, S.L.; Montgomery, R.J. The Effects of Social Influence and Cognitive Dissonance on Travel Purchase Decisions. J. Travel Res. 2014, 54, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawitri, D.R.; Hadiyanto, H.; Hadi, S.P. Pro-environmental Behavior from a SocialCognitive Theory Perspective. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 23, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazard, A.; Atkinson, L. Putting Environmental Infographics Center Stage: The Role of Visuals at the Elaboration Likelihood Model’s Critical Point of Persuasion. Sci. Commun. 2015, 37, 6–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glac, K. Understanding Socially Responsible Investing: The Effect of Decision Frames and Trade-off Options. J. Bus. Ethic 2008, 87, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, E.; Hoelzl, E.; Kirchler, E. A comparison of models describing the impact of moral decision making on investment decisions. J. Bus. Ethic 2008, 82, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J. Investment with a Conscience: Examining the Impact of Pro-Social Attitudes and Perceived Financial Performance on Socially Responsible Investment Behavior. J. Bus. Ethic 2007, 83, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepitone, A.; Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Am. J. Psychol. 1959, 72, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ester, P.; Winett, R.A. Toward More Effective Antecedent Strategies for Environmental Programs. J. Environ. Syst. 1981, 11, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Information, Incentives, and Proenvironmental Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Policy 1999, 22, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamill, R.; Wilson, T.D.; Nisbett, R.E. Insensitivity to sample bias: Generalizing from atypical cases. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G. The contemporary theory of metaphor. In Metaphor and Thought, 2nd ed.; Ortony, A., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; pp. 203–251. [Google Scholar]

- Sopory, P.; Price-Dillard, J. The persuasive effects of metaphor: A meta-analysis. Hum. Commun. Res. 2002, 28, 382–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Linden, S.L.; Leiserowitz, A.A.; Feinberg, G.D.; Maibach, E.W. How to communicate the scientific consensus on climate change: Plain facts, pie charts or metaphors? Clim. Chang. 2014, 126, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, I. The Role of Repetition in Associative Learning. Am. J. Psychol. 1957, 70, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ray, M.L. Situational Effects of Advertising Repetition: The Moderating Influence of Motivation, Ability, and Opportunity to Respond. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 12, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, S.A.; Hoch, S.J.; Meyers-Levy, J. Low-involvement learning: Repetition and coherence in familiarity and belief. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, M.-L. Repetition Increases Children’s Comprehension of Television Content—Up to a Point. Commun. Monogr. 2006, 73, 216–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn. Psychol. 1973, 5, 207–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiken, S.; Maheswaran, D. Heuristic processing can bias systematic processing: Effects of source credibility, argument ambiguity, and task importance on attitude judgment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.E. Green Advertising: Salvation or Oxymoron? J. Advert. 1995, 24, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A. Facing the backlash: Green marketing and strategic reorientation in the 1990s. J. Strat. Mark. 2000, 8, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, M.C.; Slotegraaf, R.J.; Chandukala, S.R. Green Claims and Message Frames: How Green New Products Change Brand Attitude. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, T.L.; Litzky, B.E.; Holderness, D.K. When Organizations Don’t Walk Their Talk: A Cross-Level Examination of How Decoupling Formal Ethics Programs Affects Organizational Members. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 128, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedele, A.; DeJong, P. Consumer Readings of Green Appeals in Advertisements. J. Promot. Manag. 2013, 19, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.A.; Maibach, E.W.; Roser-Renouf, C.; Smith, N.; Dawson, E. Climategate, Public Opinion, and the Loss of Trust. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 818–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. Ethical branding and corporate reputation. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2005, 10, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauß, N. The role of trust in investor relations: Guiding strategic financial communication. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2018, 23, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maibach, E. Increasing Public Awareness and Facilitating Behavior Change: Two Guiding Heuristics. In Climate Change and Biodiversity, 2nd ed.; Hannah, L., Lovejoy, T., Eds.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2019; pp. 336–346. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. The Value Basis of Environmental Concern. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. Explaining Proenvironmental Intention and Behavior by Personal Norms and the Theory of Planned Behavior1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2505–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H. Social norms and energy conservation. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Green Consumption: Behavior and Norms. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.M.; Steg, L. Value orientations and environmental beliefs in five countries: Validity of an instrument to measure egoistic, altruistic and biospheric value orientations. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2007, 38, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Value structures behind pro-environmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical Advances and Empirical Tests in 20 Countries. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Habib, R.; Hardisty, D.J. How to SHIFT Consumer Behaviors to be More Sustainable: A Literature Review and Guiding Framework. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Moser, S.C. Individual understandings, perceptions, and engagement with climate change: Insights from in-depth studies across the world. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2011, 2, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamson, W.A.; Iyengar, S. Is Anyone Responsible? How Television Frames Political Issues. Contemp. Sociol. A J. Rev. 1992, 21, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidwell, B.; Farmer, A.; Hardesty, D.M. Getting Liberals and Conservatives to Go Green: Political Ideology and Congruent Appeals. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 40, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Aaker, J. Bringing the frame into focus: The influence of regulatory fit on processing fluency and persuasion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, P.R.; Mikulincer, M.; Gross, J.T.; Stern, J.A.; Cassidy, J.A. A lifespan perspective on attachment and care for others: Empathy, altruism, and prosocial behavior. In Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications, 3rd ed.; Cassidy, J., Shaver, P.R., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 878–916. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, D.M.; Loewenstein, G.; Moore, D.A. The dirt on coming clean: Perverse effects of disclosing conflicts of interest. J. Leg. Stud. 2005, 34, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, C.L.; Howlett, E.; Burton, S.; Kozup, J.C.; Tangari, A.H. The influence of consumer concern about global climate change on framing effects for environmental sustainability messages. Int. J. Advert. 2012, 31, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinon, A.; Gambara, H. A meta-analytic review of framing effect: Risky, attribute, and goal framing. Psicothema 2005, 17, 325–331. [Google Scholar]

- Fischhoff, B.; De Bruin, W.B.; Güvenç, Ü.; Caruso, D.; Brilliant, L. Analyzing disaster risks and plans: An avian flu example. J. Risk Uncertain. 2006, 33, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Carter, P.; Blair, E. Attribute framing and goal framing effects in health decisions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 82, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S. Integration of the cognitive and the psychodynamic unconscious. Am. Psychol. 1994, 49, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeDoux, J.E. Cognitive-Emotional Interactions in the Brain. Cogn. Emot. 1989, 3, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G.; Weber, E.; Hsee, C.K.; Welch, N. Risk as feelings. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, Z.; Jansson, J.; Bengtsson, M. Cause I’ll feel good! An investigation into the effects of anticipated emotions and personal moral norms on consumer pro-environmental behaviour. J. Promot. Manag. 2017, 23, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, A. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, S.; Dilling, L. Making climate hot: Communicating the urgency and challenge of global climate change. Environment 2004, 46, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Poortinga, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Values, environmental concern and environmental behavior: A study into household energy use. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Zelezny, L.C. Values and proenvironmental behaviour. A five-country study. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 1998, 29, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, J.; Ebreo, A. Predicting recycling behavior form global and specific environmental attitudes and changes in recycling opportunities. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1580–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.A.; Lickel, B.; Markowitz, E.M. Reassessing emotion in climate change communication. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2017, 7, 850–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Cantú, S.M.; Van Vugt, M. The Evolutionary Bases for Sustainable Behavior: Implications for Marketing, Policy, and Social Entrepreneurship. J. Public Policy Mark. 2012, 31, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.E. Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1956, 70, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrand, T.L.; Van Baaren, R. Human mimicry. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 41, 219–274. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion; William Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L. Social influence approaches to encourage resource conservation: A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B. Crafting Normative Messages to Protect the Environment. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2003, 12, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, F.; Carrus, G.; Passafaro, P.; Bonnes, M. Distinguishing the sources of normative influence on proenvironmental behaviors: The role of local norms in household waste recycling. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2011, 14, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.J.; Cialdini, R.B.; Griskevicius, V. A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vugt, M.; Hogan, R.; Kaiser, R.B. Leadership, followership, and evolution: Some lessons from the past. Am. Psychol. 2008, 63, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burn, S.M. Social Psychology and the Stimulation of Recycling Behaviors: The Block Leader Approach. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 21, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.R.; Nielsen, J.M. Recycling as an altruistic behavior: Normative and behavioral strategies to expand participation in a community recycling program. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H.S.; Gangestad, S.W. Life History Theory and Evolutionary Psychology. In The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 68–95. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, S.; Loewenstein, G.; O’Donoghue, T. Time discounting and time preference: A critical Review. J. Econ. Lit. 2002, 40, 351–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczek, R.W.; Trudel, R.; White, K. Focusing on the forest or the trees: How abstract versus concrete construal level predicts responses to eco-friendly products. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 57, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vugt, M.; Griskevicius, V.; Schultz, P. Naturally green: Harnessing stone age psychological biases to foster environ-mental behavior. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2014, 8, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T.; Gardner, B.; Verplanken, B.; Abraham, C. Habitual behaviors or patterns of practice? Explaining and changing repetitive climate-relevant actions. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2015, 6, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Wood, W. Interventions to Break and Create Consumer Habits. J. Public Policy Mark. 2006, 25, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.G.; Miller, D.T.; Lerner, M.J. Committing Altruism under the Cloak of Self-Interest: The Exchange Fiction. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 38, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtens, B. What drives socially responsible investment? The case of the Netherlands. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strauß, N. Communicating Sustainable Responsible Investments as Financial Advisors: Engaging Private Investors with Strategic Communication. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063161

Strauß N. Communicating Sustainable Responsible Investments as Financial Advisors: Engaging Private Investors with Strategic Communication. Sustainability. 2021; 13(6):3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063161

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrauß, Nadine. 2021. "Communicating Sustainable Responsible Investments as Financial Advisors: Engaging Private Investors with Strategic Communication" Sustainability 13, no. 6: 3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063161

APA StyleStrauß, N. (2021). Communicating Sustainable Responsible Investments as Financial Advisors: Engaging Private Investors with Strategic Communication. Sustainability, 13(6), 3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063161